FUNCTIONAL BUDGETS

Sample Data

VT Ltd produces two products – X and Y. The products pass through two departments – Department 1 and Department 2. The following standards have been prepared for direct materials and direct wages:

Sales Budget

The sales budget will frequently be the starting point of the budget, and it is in our example. The sales figures will usually determine the production requirements – subject, as in this case, to any required adjustment to the stocks of finished goods. The sales budget will be derived from salespeople’s reports, market research, or other intelligence or information bearing on future sales levels and demand for the company’s products. The sales budget would be analysed according to the regions or territories involved, with monthly budget figures for territories, salespeople and products, so that sales representatives would have specific targets against which actual performances could be measured.

Production Budget

The purpose of this budget is to show the required production for the coming year, so that production scheduling can be completed in advance and individual machine loading schedules can be prepared. This will enable the production department to assess the budgeted usage of plant, the labour requirements and the extent of any under- or over-capacity. As with the sales budget, the total annual requirements must be analysed into monthly figures.

Materials Purchase Budget

This budget sets out the purchasing requirements for each type of material used by the organisation, so that the purchasing department can place orders for deliveries, to take place in accordance with production requirements – the essential need being that production should not be held up for lack of materials. Purchase orders should be placed, and deliveries phased, according to the production schedules, care being taken that no excessive stocks are carried. The standard for the products will also specify the quality of material required, so that the purchasing department will be responsible for obtaining the materials required, of the standard quality.

Direct Labour Cost Budget

This budget shows the number of direct labour-hours required to fulfil the production requirements and the monetary value of those hours. Departmental figures are given, so that departmental supervisors are made aware of the labour-hours and costs over which they are expected to exercise control. Periodic reports would be made to supervisors, showing the output achieved and the relevant standard hours and costs for that output (and, where necessary, the reports required on any significant variances from the standards).

Production Overhead Budget

The variable and fixed overheads are shown by department. The departmental supervisors will be expected to exercise control over those items for which they are responsible, and monthly reports, highlighting the variances from budget, will be provided to assist them. The variable overheads are expressed as amounts per direct labour-hour – but these could also be shown in relation to some other factor, such as machine time, units of production, materials to be consumed, or other relevant factors. In practice a combination of these factors might be used.

Selling and Distribution Overheads Budget

As with other overhead budgets, the object of this budget is to identify the overheads to be controlled by the management – in this case the sales management. Further analyses of the overheads would be required to show the budgeted costs on a monthly basis, and by regions and representatives where appropriate.

Administration Overheads Budget

The administration overheads are likely to be mainly of a fixed character, and not affected by production or sales levels, except where there are wide fluctuations. These overheads will cover the general administration and accounting services of the organisation, and they will be the responsibility of the chief executive concerned. Separate budgets for the accounting, company secretarial and other departments will be required in larger organisations. The budgets will be prepared after detailed studies have been made of the level of service required to provide the necessary accounting, secretarial and other administrative services needed. Where a complete review is required, an organisation and methods study may be undertaken. Monthly reports will show actual and budgeted results, as with other functions, and variances shown for further investigation. (The costs in this problem have been assumed to be entirely fixed.)

MASTER BUDGETS

(This is not examinable for Formation 2; however it is useful for information purposes)

Budgeted Trading and Profit and Loss Account

This account is part of the master budget as it brings together all the functional and subsidiary budgets and it shows the expected trading profit or loss based on the sales and cost budgets previously prepared. In the light of these results, the management may decide to recommend changes to the sales and cost figures, to bring the expected results into line with a required return on capital or gross and net profit percentages related to sales. Once the final figures have been approved, the budgeted trading and profit figures become the target for the company as a whole.

Budgeted Balance Sheet

This also forms part of the master budget, and it shows the expected overall financial position resulting from the budgets. It enables assessments to be made of the return on capital and ratios of profitability and liquidity – for example, the current asset/current liability position, credit collection periods, and other financial ratios. This may also be part of a review process in which some revisions may be required before final approval is given.

CASH BUDGET

This budget enables management to see the timing of projected cash flows and the net cash flow position for each period. Monthly cash flow figures would be provided to show the anticipated cash position at each point. In the light of this budget, it may be necessary to make arrangements for overdraft facilities for short-term needs or investment of surplus funds. In very large organisations the management of funds may require constant attention to ensure that effective use is made of all available funds. Also separate cash budgets may be required for operational cash flows and financing cash flows. The operational cash flows relate to trading operations, and financing cash flows to longer-term financing with related interest charges.

Construction of Cash Budgets

It is very important that you understand how to construct a cash budget (this topic forms a frequent examination question).

Cash budget detail the cash effect of all transactions included in a company’s budgeted profit and loss account and balance sheet. There are two methods of preparing them. One method calculates receipts and payments, whilst the other looks at the change in the opening and closing balance sheet positions

Explanatory notes on preparation of cash budget:

Sales

All sales are made on one month’s credit. This means that January’s sales will be paid for in February, February’s sales will be paid for in March and March’s sales will be paid for in April.

Cash from March’s sales will be received in April, which is not covered by the cash budget. At the end of March, RWF90,000 is owed to the company which will be shown as debtors in March’s balance sheet.

Purchases

The company obtains one month’s credit on all its purchases. January’s purchases will be paid for in February. February’s purchases will be paid for in March and March’s purchases will be paid for in April.

At the end of March the company owes its suppliers RWF30,000, which will be shown as part of creditors in March’s balance sheet.

Wages and Salaries

Wages are paid out in the same month as the expense is incurred.

Depreciation

Depreciation covers the reduction in value of a company’s fixed assets. Depreciation is not a cash payment. It is an accounting provision which reduces profits and the value of assets in the balance sheet.

Cash flow statements are concerned only with cash payments and cash receipts. As depreciation does not affect cash, it will not appear in a budgeted cash flow statement.

Other Overheads

Other overheads are bought on one month’s credit. The cost, included in January’s profit and loss account, is included in February’s cash flow, and so on.

At the end of March the company owes its suppliers RWF22,000 which will be shown as part of creditors together with the RWF30,000 owed for its other purchases.

Cash Balances

The opening cash position in January is taken from the balance sheet as at 1 Jan.

The closing cash position for January becomes the opening cash position in February. February’s closing cash position becomes the opening cash position in March.

Comparison of Opening and Closing Balance Sheets Method

It is also possible to prepare a cash budget by examining the opening and closing balance sheet positions.

Completion of the cash budget on a receipts and payments basis will identify the level of debtors and creditors. The debtors figure will represent sales made on credit for which payment has not been received. The creditors figure will represent purchases made on credit that have not yet been paid for. The statement will also establish the cash or bank overdraft position.

As an alternative, it is possible to calculate debtors and creditors by using target ratios or other information that will always be given to you in an examination question.

Cash Flow Statement

You should be aware from your financial accounting studies that, from a budgeted balance sheet and profit and loss account, it is possible to prepare a cash flow statement. The layout of this type of statement is presented below. The information in this statement is taken from Cashflow Ltd’s accounts detailed earlier.

This type of statement starts with a company’s profits. It then adds back the amount of depreciation included in the profit and loss account as this does not involve a payment of cash. Operating profit is then further adjusted for changes in the working capital position:

- An increase in stocks will reduce cash.

- A reduction in debtors means that the company has received a greater value of cash than it has invoiced out in the form of credit sales. This will benefit a company’s cash position.

- An increase in the value of creditors means that the company has paid less to its suppliers than it has been allowed in credit. This will improve the cash position.

The effect of raising new share capital will benefit cash and the payment of tax and dividends and repayment of a loan will obviously reduce the cash balance.

The final figure in the statement is the company’s net cash flow for the period, which is represented by a change in the company’s cash position. The opening cash position was RWF10,000 and the closing balance was RWF81,000. The company must therefore have generated a positive cash flow of RWF71,000.

The advantage of this type of statement is that it clearly identifies those areas of the business that must be controlled in order effectively to manage its cash resource:

− Profit must be maximised.

− Capital expenditure must be controlled. Investment should lead to improved levels of profitability.

− Stock must be kept to a minimum.

− Debtors must be kept to a minimum.

− Creditors must be controlled so that the maximum benefit is obtained from this form of finance.

We will look at cash flow statements again in a later study unit.

Benefits of Cash Budgets

The preparation of cash budgets will also generate the following benefits:

- Cash budgeting highlights the impact that all other decisions have on a company’s financial resource.

- Cash may be a limiting factor and restrict a company’s plans. The preparation of a cash budget will indicate if this is the case.

- Budgeting will identify any cash problems that may occur during the period covered by the budget. Advance warning will enable a company to take corrective action.

- Cash budgets are very useful documents when talking to banks and other financial institutions. These organisations want to see that a company is controlling its cash, and that it will be in a position to meet its obligations as they fall due.

FLEXIBLE BUDGETS

Use of Flexible Budgets

Fixed budgets are used to plan the activity of the organisation. Cost control begins by comparing actual expenditure with budget. Remember, though, that if the level of activity differs from that expected, some costs will change, and the individual manager cannot be expected to control the whole of that change. If activity is greater than budgeted, some costs will rise; if activity is less than budgeted, some costs will fall. The question is whether the manager has kept costs within the level to be expected, given the activity level.

A flexible budget, as we mentioned in an earlier study unit, is one which – by recognising the difference in behaviour between fixed and variable costs in relation to fluctuations in output, turnover, or other variable factors, such as number of employees – is designed to change appropriately with such fluctuations. It is the flexible budget which is used for control purposes, not the fixed budget we have discussed so far.

Cost Behaviour

In order to understand flexible budgets, we must recall our earlier definitions of fixed and variable costs:

Fixed Cost

This is a cost which accrues in relation to the passage of time and which, within certain output and turnover limits, tends to be unaffected by fluctuations in the level of activity. Examples are rent, , insurance and executive salaries.

Variable Cost

This is a cost which, in the short term, tends to follow the level of activity. Examples are all direct costs, sales commission and packaging costs.

Semi-variable Cost

This is a cost containing both fixed and variable elements, which is, therefore, partly affected by fluctuations in the volume of output or turnover. There are two main methods of predicting semi-variable costs at various levels of output or turnover:

Separation of Fixed and Variable Elements

Provided the cost is known for two different levels of output/turnover, the fixed and variable elements can be separated, and the level of cost at any other level of output/turnover predicted. If more than two items of data are available, the highest and lowest are selected (the high and low point method).

) Graphical Method for ‘Curve Expenses’

The calculation made in (i) is an oversimplification of the situation that is found in practice in respect of semi-variable costs: it was assumed that, after a certain initial expense, incremental costs varied in direct proportion to output – in other words, that the graph of the cost looked like that in Figure 10.1:

Discretionary Cost

This is a fourth category of cost, which may be incurred or not, at the manager’s discretion. It is not directly necessary to achieving production or sales, even though the expenditure may be desirable. Examples are research and development expenditure.

Discretionary costs such as this are a prime target for cost reduction when funds are scarce, precisely because they are not related to current production or sales levels. This might be a very short-sighted policy – nevertheless, it is useful to have these costs separately identified in the budget.

Controllable Costs or Managed Costs

As we know, the emphasis in budgeting is on responsibility for costs (budgetary control is one form of responsibility accounting). The aim must be to give each manager information about those costs he can control, and not to overburden him with information about other costs. A controllable cost is one chargeable to a budget or cost centre which can be influenced by the actions of the person in control of the centre.

Given a long enough time-period, all costs are ultimately controllable by someone in the organisation (e.g. a decision could be taken to move to a new location, if factory rent became too high). Controllable costs may, however, be controllable only to a limited extent. Fixed costs are generally controllable only given a reasonably long time-span. Variable costs may be controlled by ensuring that there is no wastage but they will still, of course, rise more or less in proportion to output.

Notes: (a) Supervision

This is a semi-variable expense, and it rises only when extra hours are worked – e.g. when the number of employees increases, or when the firm increases the number of supervisors. The allowance for 2,001 hours to 2,400 hours would be RWF310, and between 2,801 and 3,200 the allowance would be RWF430.

Following this line of reasoning, up to and including 3,600 hours would have an allowance of RWF490. Anything above 3,600 would have a budget of RWF580 – i.e. including the extra RWF30.

Depreciation

This is normally a fixed expense – but fixed only within certain ranges of production activity. Remember that no expense is fixed over a long period or over a wide range of production activities.

Consumable Supplies

This is a variable expense in this example – it rises or falls in a direct ratio to the number of hours worked.

Heat and fans

This is a semi-variable expense; probably the figures are based on past experience or a technical estimate.

Power

This is a variable expense but, at certain levels of activity, power is supplied at a cheaper rate.

Cleaning

This is a semi-variable expense.

Repairs

Again, a semi-variable expense. Presumably, when the number of hours worked increases, more repairs will be required – but not in a direct ratio to the increase in hours.

Indirect Wages

These are, in this case, a variable expense.

Rent

Here, this is a fixed expense.

Calculation of Departmental Hourly Overhead Rate

It is most important to realise that this rate is always calculated from the fixed budget – not from a flexible budget. This is because the rate has to be applied throughout the budget period as it proceeds, and the actual level of output is not known until the end of the period, so that we would not know which flexible budget to choose. Remember that the fixed budget is used for planning purposes, the flexible budget for control.

The difference between the flexible budget at a certain level of activity and the actual cost incurred is, as we know, termed a variance. This may be either favourable or adverse.

. ZERO-BASE BUDGETING (ZBB)

Basic Approach

Some aspects of the budget are easy to quantify. For example, if the required output is known then the materials budget can be calculated from known data – material usage per unit of output, wastage, planned stock changes, expected losses, etc. However, many aspects of the budget cannot be so easily quantified – the outcome of indirect and service areas cannot easily be related to sales and production targets. In these areas, traditionally, an incremental approach to budgeting has been adopted. Typically, the manager starts from his current head count and activities and estimates how much more (or, in times of hardship, less) he needs.

The advantages of this approach are:

- It is based on known factors (current expenditure).

- It is probably the least time-consuming approach to budgeting.

But:

- It encourages an easy-going, ‘live and let live’ approach.

- Considerable inertia is built into the company’s procedures. Change will be difficult to manage.

- Existing services are accepted as necessary without question, whereas a critical eye might see worthwhile savings.

It was to combat the disadvantages of traditional budgeting that zero base budgeting (ZBB) was introduced. ZBB is an attempt to eliminate unnecessary expenditure being retained in budgets. It rejects the common approach of setting budgets by taking last year’s expenditure as the starting point for this year’s budget, and instead requires that the budget be built up from scratch. In this way activities are rejustified each year. The CIMA defines ZBB as: “A method of budgeting whereby all activities are re-evaluated each time a budget is formulated.

Each functional budget starts with the assumption that the function does not exist and is at zero cost. Increments of cost are compared with increments of benefit, culminating in the planned maximum benefit for a given budgeted cost.”

The way in which ZBB is implemented will vary from one organisation to another, but the following steps may be taken:

- The organisation is divided into decision units, each representing a readily identifiable part of the business, such as a function, division, department or section.

- Managers will be required to prepare decision packages, i.e. documents defining the objectives, targets and resources which will be needed. It may also be necessary to prepare alternative budgets based on different levels of production or service.

- Where different levels of budgets are set for decision units, a grading of priorities will be required in order to assist in the final choice of packages and allocation of available resources.

The technique is most useful when applied to service and support functions such as research and development and administration, where there is considerable discretion as to the level of expenditure, and it has been used in non-profit-making organisations such as local government. When funds are scarce, such a technique is the only way of introducing new projects, as otherwise existing projects always have first claim on the scarce resources.

Expenditure may be committed (the minimum essential to meet statutory requirements, for example for safety, or to ensure operations continue). It may also be engineered (changing with activity levels) or discretionary (depending on management, e.g. conference costs).

ZBB exercises are very time-consuming and costly and some organisations would only carry out a full ZBB approach, say every three to five years, and would use previous years’ costs and revenues as a starting point in the intervening years. There may also be communication problems in explaining ZBB to managers, and lack of co-operation as managers see ZBB as a threat to their ‘empires’ and status.

How the System Works

Where ZBB differs from the traditional approach is that managers must scrutinise very carefully from scratch their future requirements In other words, in principle it ignores all previous expenditure and performance associated with the company’s activities, and looks afresh at these activities with a view to possible cost reduction, elimination of an activity, new ways of achieving objectives, or redistribution of resources.

A company operating ZBB demands full co-operation and participation from its managers in producing their respective assessments of requirements. They are made fully responsible for their decisions. The process requires each manager to justify his total budget (and, subsequently, justify the use of resources).

Decision Packages

The system requires a manager to prepare decision packages for all activities (e.g. projects, job functions) within his responsibility, and these packages must clearly lay out the minimum level of performance essential, and any additional costs and additional benefits linked with these costs. Decision packages must be produced where it is considered that there may be alternative approaches (buy-in or sub-contract, for example) and finally an indication (cost effect) of not continuing with any particular activity. Decision packages represent units of intended activity.

Examples of activities within the management accountant’s responsibility could be: material control unit; payroll purchase ledger; sales ledger; data processing unit. The manager of each of these areas would be required to produce decision packages on the basis just outlined.

Ranking and Evaluation

Having produced batches of decision packages, the manager would then rank them in order of importance, after carrying out a cost/benefit analysis for each package. All packages would then be forwarded to top management, who would compare and evaluate the relative organisational needs, and fund accordingly – taking due note of high and low priority packages. Their considerations would extend to those decision packages which might cover redundant or duplicated activities.

Need for Educated Managers

In using ZBB there is a strong inference that managers are well informed in the area of information collecting and evaluation. They must, further, be trained in cost/benefit analysis, in order to rank the decision packages. This is a potential weakness – not in the system of ZBB itself, but in the means of producing it.

Comparison with Traditional Budgeting

Whereas traditional budgeting paints with a very broad brush, assuming that all activities will continue during the budget year, ZBB paints with a thin brush, providing very fine economic detail (and, thus, fine control of individual activities and operations within the organisation). Because the funding of activities is considered in detail by means of decision packages, company resources are carefully directed and monitored

Implications and Value of ZBB

- ZBB, in principle, starts from scratch but, in practice, it would start from a minimum cost level for each activity, and build up decision packages by changing the inputs. This contrasts with traditional budgeting which assumes all activities are necessary and continuing – there is very little ‘weeding out’.

- Managers are made aware of the corporate effect of their departments’ operations.

- ZBB allows questions to be asked before committing funds, and not afterwards, as in traditional budgeting.

- Inefficient, redundant or obsolete operations are identified before the budget is finalised.

- Greater managerial detail is available to the top management.

- Low and middle managers are made fully aware of the smallest details of the many activities for which they are responsible.

- Managerial education must be at a very high level, with its attendant high training cost.

Question

A manufacturing company intends to introduce zero-based budgeting in respect of its service departments.

- Explain how zero-based budgeting differs from incremental budgeting and explain the role of committed, engineered and discretionary costs in the operation of zero-based budgeting.

- Give specific examples of committed, engineered and discretionary costs in the operation of zero-based budgeting.

Answer

Incremental budgeting uses the budget of the previous year as a starting point and adjustments are made for volume, price changes and efficiency. The basic structure of the budget is regarded as acceptable as it stands.

Zero-based budgets place the onus on the departmental manager to justify all proposed expenditure. Nothing is accepted as being necessary expenditure. Each department will need to consider possible options for the year, which will be ranked and used to decide total budgets within the overall master budget of the organisation.

The role of a committed cost in zero-based budgeting is to set the minimum level of expenditure necessary for statutory requirements to be met or for business operations to take place.

An engineered cost is one that is incurred in proportion to activity. These differ under each level of activity projected under zero-based budgeting.

Discretionary costs are those which management decide whether to incur or not. They will be assessed on a cost/benefit analysis and accepted or discarded depending on the result.

The following are examples of each kind of costs. You may have suggested others relevant to your organisation.

Committed:

− Anti-pollution measures required by law

− A minimum level of maintenance and repair costs

− Requirement of a limited company to prepare annual accounts backed by

adequate accounting records; cost of audit Engineered:

− Machine guards for each machine used

− Routine replacement of laser printer cartridges − Costs of invoicing per order/statement per customer Discretionary:

− Updating conferences; attendance expenditure

− Expenditure on management accounting function

BUDGETARY CONTROL AND STANDARD COSTING – BEHAVIOURAL CONSIDERATIONS

Throughout our studies on budgetary control and standard costing, the emphasis has been on the economic aspect. There is, however, another – and very important – side to the concept, and this is the effect on the human beings who will operate – and be judged by – the budgetary system.

It was only in the 1980s that the results of years of study of interpersonal relationships percolated into the field of management accountancy. It is now recognised that failure to consider the effect of cost control on the people could result in a lowering of morale, reducing motivation and company loyalty. The effect of this would be a reduction in profits or cost-saving.

• Control Aspects of Budgeting

In preparing budgets in the first instance, managers should be consulted in respect of their anticipation of costs which are controlled by them. It is true that an overall objective is set by the higher levels of management, but the actual achievement of that objective is left for the lower levels of management to plan.

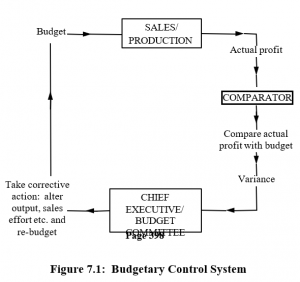

Control is achieved by continuous comparison between actual and budgeted results. Instead of using the term ‘variances’, as used in standard costing, it may be better to call them differences.

These differences could be related to how well managers are performing their functions. It is necessary to relate the differences in results to performance indicators.

The ultimate purpose of preparing budgets and calculating variances (differences) between actual and budgeted results is to initiate managerial action. In the case of controllable variances, speedy authoritative action would result in stemming adverse variances or encouraging favourable variances. In the case of non-controllable variances, caused by external factors, swift management action to search for alternatives would be necessary.

• Levels of Management Information

It is necessary to consider the frequency of comparative information made available to management at different levels. Lower levels of management require information speedily, for example weekly, to stem adverse movements, while higher levels of management, to prevent unnecessary paperwork, could receive summarised information, for example on a monthly basis.

The information given to management should be in units easily understood by the level to which it is directed. The lower levels may be more interested in labour or machinehours or kg materials used, while higher levels would require the information in monetary values.

• Motivation and Co-operation

Any system of cost control, to be fully effective, must provide for motivation and incentive. If this requirement is not satisfied, managers will approach their responsibilities in a very cautious and conservative manner. Praise should be forthcoming if budgets are bettered: unfortunately, it is losses and adverse variances which attract attention and investigation.

Personal goals and ambitions are strongly linked with organisational goals; these personal goals may include a desire for a higher social standing and a betterment of the individual’s status. To satisfy the goals of both the organisation and the individual, there must be goal congruence. Without this mutual understanding, the economic atmosphere of the organisation will be much less healthy.

The success of a budget procedure depends, at all times, on people. They must work within the system in an understanding and co-operative manner. This can be achieved only by individuals who have a total involvement at all stages of the budgetary procedure, and who share in its favourable as well as its adverse revelations.

• Results of Goal Antagonism

Some of the most damaging and negative results of non-motivation created by a budgetary control system are:

- Suspicion of being manipulated by the budget system: it is seen as a pressure device.

- Competition between cost centres may arise and thus diminish the unifying effect of budgetary control.

- A discouraging atmosphere will be created by failure to commend favourable results, and by criticism of adverse results.

• Other Effects on Management Behaviour

The way standard costing and budgetary control systems are used can influence management behaviour in a number of other ways:

- Standard costing and budgetary control systems concentrate on the short term. It must be recognised that managers may therefore be placed in a situation whereby they make decisions that satisfy the short-term control systems but damage the future position of the business. For example, a manager may decide to reduce his research and development costs in order to stay within budget. This may satisfy the short-term objectives but will clearly have long-term implications for the business.

- Standard costing and budgetary systems sometimes include in operating statements a number of costs over which the manager has no control. This approach can be counter-productive and demotivating as a manager cannot be held responsible for costs that he cannot control.

- Unless constant vigilance is maintained it will be possible for managers to incur expenditure but have it charged to another manager’s cost centre. This practice can result in conflict within the business which can cause a great deal of harm.

- Managers may feel that they have fully to spend their budgets so as to justify their original predictions and in so doing avoid having their following year’s budget reduced. This approach may cause waste within the business.