NATURE OF MARKETS

In economics, a market is an area within which the forces of demand and supply for a particular “economic good” can communicate and interact, so that the good can be transferred from suppliers to buyers.

This definition contains a number of important elements which have to be considered whenever we analyse a particular market or compare one market with another. Let us look at these elements.

The “Economic Good”

A “good” is any benefit which accords utility to people, and to obtain which they are prepared to sacrifice scarce resources. The term “utility” is chosen because it avoids the idea that there has to be any particular virtue in the “good”. If people want something and are prepared to make some sacrifice of their resources (usually represented by money) to obtain it, then we assume they gain utility from it, even if it does them actual harm. Thus, economists may analyse the markets for tobacco or heroin.

The “good” can be a physical object, such as a motor car, or a service. It can be a consumer, or intermediate, or capital good, or a factor of production. In this course, we are concerned chiefly with consumer and production factor markets.

We must be careful to give a precise definition of any market we are considering. The total market for motor cars contains a number of subsidiary markets – e.g. for sports cars or saloon cars. We must always distinguish the market for the whole class of product from that for a particular brand or other sub-division. Thus, the market for the Toyota Corolla is distinct from the market for small cars – which, in turn, is distinct from that for private cars and from the market for personal transport as a whole.

Confusion sometimes arises when we are concerned with the price elasticity of demand for a product. The class or product may be price inelastic, whereas a particular brand may be price elastic. For example, petrol in general may be price inelastic, but the price of K’s petrol can be price elastic. The motorist has to have petrol, but he may have the choice of a number of filling stations offering a variety of petrol brands at different prices, and he may also be prepared to go a few miles out of his way to obtain the cheapest brand of petrol.

Market Area

We need to examine the market area when considering the conditions of a particular market. The area is that within which communication takes place, and not simply where final negotiation is arranged. A sale of antiques or fine paintings may take place in a small room anywhere in the world but, beforehand, catalogues may have been sent to dealers throughout the world, and many foreign buyers may be represented by their agents when the sale or auction actually takes place. In contrast, a small retail shop may be concerned with a market area restricted to a few streets or a single housing estate. The goods it sells may be available in other shops serving different market areas nearby.

Communications and Transport

The extent of the market is really determined by the efficiency of communications and the ability to transport the goods from seller to buyer. X does not really have a choice between goods A and B if he does not know that B exists, or if he has no means of comparing price or quality. Thus, if I am buying tomatoes on one side of the town, I cannot really compare them with those on sale on the other side of the town, even if someone tells me that they are several pence cheaper. I need to be sure that they are products of similar quality.

Some markets have developed very precise descriptive terms. The use of these terms, for example, in some of the basic commodity exchanges, enables buyers and sellers to know exactly what quality goods are being traded.

There can be an effective market only if it is possible to transfer the product from seller to buyer. Any barrier to transfer will limit the market area.

Conditions of Supply and Demand

There can be a market only if there are suppliers able to deliver the goods at the time agreed, and buyers with the necessary resources to acquire them.

The good does not necessarily have to be in existence at the time it is traded, as long as there is a guarantee that it will be available when and where agreed. The ability of certain commodity markets to trade in crops not yet grown, or metals not yet mined, is well known; but a manufacturer can also agree to sell goods not yet made, and a few authors can even sell books not yet written! However, both buyer and seller must have a clear idea of the product that is to be delivered. The more precise the definition of a product, the easier it is to sell in this way.

The desire to buy must also be realistic. Many of us would like to possess an ocean-going cruiser or a private aeroplane; but few of us, unfortunately, have the resources to acquire and operate them.

FUNCTIONS OF MARKETS

A market has other purposes, apart from providing the means whereby a good is transferred from supplier to buyer.

Information

The market serves to convey information about the conditions of supply and demand. I may go to a furniture store, not just to buy a piece of furniture but to see what furniture is available and at what price. The better the communication system within the market, the more information I can gain about what can be bought – and the more chance I have of achieving full utility from my purchase.

This communication function works both ways. The market also informs actual and potential suppliers about the strength and pattern of demand – about what people want to acquire and what level of price they are prepared to pay. Suppliers need this information in order to plan production.

The problem from the supplier’s point of view is often that the information comes too late. He has to make supply decisions before accurate information is available. The supplier wants to know today what market conditions are going to be like tomorrow. The impossibility of achieving accurate forecasts all the time is one of the main sources of business risk.

Establishing Price

Arising out of the two-way communication function is a further most important function – that of establishing the price at which the buyer is willing to buy and the supplier willing to supply. How this may be achieved is the subject of much of the rest of this study unit.

It is such an important function of the market that some large firms ensure that certain markets continue to operate only because they need a reliable mechanism for price-setting. The large manufacturing companies do not really need to buy metal on the London Metal Exchange – they can obtain all they need direct from suppliers. But they do need to know the conditions of demand and supply in the main areas where metal is bought and sold. By keeping the metal exchange in operation, they obtain this information, which provides a price-setting mechanism and so helps to reduce some of the uncertainties which they have to face in obtaining essential materials.

PRICES IN UNREGULATED MARKETS

Definition of Unregulated Market

The term “unregulated” here means not subject to any price-setting regulation. An unregulated market can be subject to detailed regulations regarding the conditions of payment and transfer and the procedures for settling disputes. These, however, assist rather than impede the free communication of buying and supplying intentions, and allow them to interact in order to establish a market price. An unregulated market is, thus, one in which the forces of supply and demand are free to interact, without any form of outside price control.

We tend to think of regulation in terms of control by the State or its agencies, but a market can, of course, be controlled in other ways. Certain local art and antiques auctions are reputed to have been controlled by rings of dealers who agree not to bid against each other and to share purchases among themselves after the auction. This is not an unregulated market! The prices paid for goods at such an auction are not “market” prices because they do not reflect the true conditions of demand.

Equilibrium Price

The equilibrium price is the one at which the intentions of suppliers are just matched by the intentions of buyers, i.e. where the amount of the good demanded is just equal to the amount provided. In this state there is no pressure from either supply or demand to move away from this price, so the market forces are in a state of rest – in equilibrium.

We have examined the concepts of supply and demand schedules and “curves”. If we put supply and demand schedules and curves together, we can arrive at the equilibrium price, i.e. the “market” price.

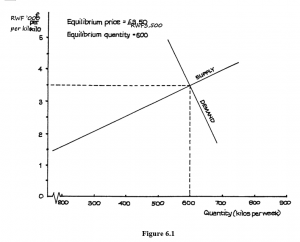

Figure 6.1

We can see from the schedules and the graph that it is only at price RWF3,500 (600 kilos per week) that the intentions of producers and buyers are the same. At any higher price, producers will be supplying more than buyers are willing to buy. At any lower price, producers will not be supplying enough “Whizzo” to meet demand. RWF3,500 is the equilibrium price, and 600 kilos per week the equilibrium quantity. As long as neither set of intentions changes, there is no incentive for any movement away from this price and quantity, once it is achieved.

Changes in Intentions – Shifts in the Curves

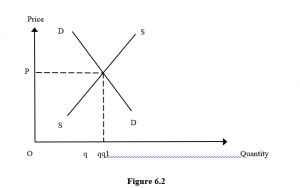

We can show the concept of equilibrium price and quantity in a general graphical model, as in Figure 6.2. Here, equilibrium price is Op and equilibrium quantity Oq – the price and quantity level where the supply and demand curves intersect. We can develop this approach to analyse the result of movements in the supply and demand curves.

Change in Either Demand or Supply

Look at Figure 6.3. Here there is a shift in buyers’ intentions, caused perhaps by a change in taste, supported by an increase in advertising. The result is a movement of the demand curve from DD to D1D1.

In this model, supply intentions remain unchanged. The result is an increase in the equilibrium price and quantity from Op, Oq to Op1, Oq1.

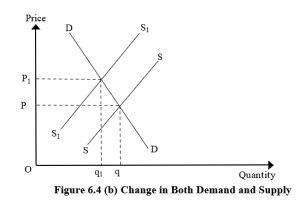

We can use the same technique to illustrate the effect of a shift in suppliers’ intentions. This is shown in Figure 6.4, where supply falls from SS to S1S1. Demand intentions remain unchanged (DD) and the equilibrium price and quantity move from Op, Oq to Op1, Oq1.

Price rises and quantity traded in this market falls.

Figure 6.4 Change in Both Demand and Supply

So far, we have considered only a possible shift in demand or supply. In practice, of course, a movement in one is likely to influence the other through the effect on price and quantity.

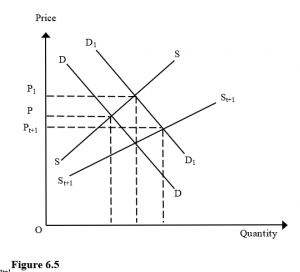

Suppose there is a major increase in demand, represented by a movement of the demand curve in Figure 6.5, from DD to D1D1. This shift, if supply remains unchanged at SS, results in an increase in equilibrium price from Op to Op1, and in quantity from Oq to Oq1.

Now suppose that this increase in quantity makes it worthwhile for one or more producers to develop new production methods, so that the good can be mass-produced at a lower unit cost. The result, after a time interval, is to shift the supply curve from SS to St+ 1 St + 1. Here the t + 1 indicates a change in time-period.

The new supply schedule, combined with the increased demand, produces a fresh equilibrium price and quantity at Opt + 1, Oqt + 1. We have the apparently unusual result of an increase in demand resulting in a reduction in market price. Note, however, that this can happen only when given some rather special assumptions about the stage of a product’s development and the possibility for change in supply conditions.

1Figure 6.5

Normally, we expect an increase in demand to raise equilibrium price and quantity. This is the direct effect. The later reduction in price can result only from a shift in the supply curve, indicating a completely new set of supply conditions.

A somewhat similar process can be initiated by a change in technology allowing mass production at a reduced price. Here, there is first a shift outwards in the supply curve. Demand then rises, but not enough to stop the price from falling. Consider the market for pocket calculators in this light.

PRICE REGULATION

Reasons

If price and quantity will always move to an equilibrium provided economic markets are left alone, we must ask why governments and other agencies should ever wish to intervene. In practice, there are several reasons, of which the following are among the most common:

Social Unacceptability

If the price resulting from an unregulated market were considered to be socially unacceptable, as causing hardship or conflict in the community, attempts might be made to control it. This could happen in a period of food shortage caused by war and/or climatic disaster, and also if there were a shortage of housing in urban areas sufficient to cause hardship and increase risks of disease, crime and other social evils.

Incomes of Producers

Attempts might be made to maintain high prices if it were desired to raise the income of producers and their employees. This is one of the motives of the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

Stability of Supply

Some markets are notoriously unstable because of unplanned variations in supply, caused by weather and other circumstances beyond the control of producers. In these cases, attempts may be made to control prices to ensure greater stability in the market.

Effects of Price Controls

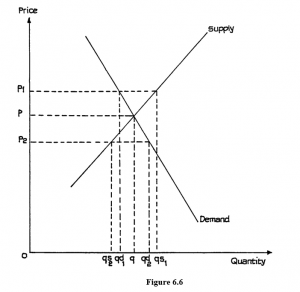

If prices are controlled without any attempt also to control demand and/or supply, the result can be the opposite of that intended. This is illustrated in Figure 6.6.

Figure 6.6

Looking at the diagram, if price is fixed at p1, quantity supplied (qs1) is more than that demanded (qd1), and there is surplus production.

If price is fixed at p2, quantity demanded (qd2) is more than that supplied (qs2), and there is a shortage.

Only at price p will quantity supplied = quantity demanded.

Here, we see that any attempt to fix prices at a level other than the market equilibrium price of p will produce either surplus production (fixed price p1 > p) or a shortage (fixed price p2 < p).

We are forced to the conclusion that, on their own, price controls are ineffective. Governments and other bodies must identify the real problem and seek to solve that. For example, if the problem is lack of adequate supply (food or housing shortage), then the government must either increase supply, e.g. by making additional payments, called subsidies, to suppliers, or by entering the market as producers or importers, or, if these remedies are impossible, it must ration the available supply among consumers in a way that the community regards as acceptable.

Such measures may be effective, at least for a time, though they may be expensive to administer and control. The government, or other body, must decide whether the social benefits to be gained from market regulation justify the cost and opportunity costs of the resources used in maintaining the regulations. Care must also be taken to ensure that the regulations themselves do not discourage suppliers to the extent that the basic objects of the policies are defeated. The heavy bureaucracy created by many schemes in the so-called planned or socialist economies often significantly discourages total production. If the problem is excess supply, then the government may seek either to stimulate demand, e.g. by reducing prices through the payment of subsidies, or to reduce supply by encouraging or paying producers to leave the market, as in the case of European Union measures to reduce European milk and wine supplies.

The most difficult problems often involve unplanned fluctuations of supply, when the plans of regulatory bodies can be upset by unusually good – or bad – crops owing to the weather. If there are fairly regular cycles of over- and under-production, and demand is reasonably constant, and if it is possible to store the crops, then the government can apply a mixture of controls over prices and production combined with purchases of over-production to keep in store for release in periods of under-production. However, it is found that the guaranteed prices that usually form part of such policies lead inevitably to steady increases in production, so that the government finds itself storing quantities of goods that it has little hope of ever releasing for resale, except at very low prices to people in other parts of the world. It may even have to give away some of the surplus produce. Such policies then become a heavy burden on taxpayers and lead to hostility from the community.

It is clear that governments which embark on market-intervention policies may, and often do, find that they become involved in increasingly difficult and expensive measures that do very little to solve the problems they were meant to eliminate.

MARKET DEFECTS – THE CASE FOR A PUBLIC SECTOR

Defects in Market Allocation

In very many cases, unregulated markets and the price system are effective and efficient ways of allocating resources and, as we saw in the previous section, some forms of well-meaning government intervention can actually make worthy social objectives more difficult to achieve. Nevertheless, this does not mean that unregulated markets are always perfect. The existence of some defects is widely accepted and among the main problems are:

Inequalities of Income

One of the virtues claimed for the unregulated market is that it makes the consumer sovereign and that resource allocation responds to demand pressures. However, if we imagine that consumers influence allocation by votes cast when they buy or refrain from buying goods and services, we have to admit that some consumers have more votes than others and large numbers have very few votes. Markets respond quickly to those groups which have the most purchasing power. This does not always ensure that resources are allocated in ways that meet the social expectations of the community.

It has always been difficult to ensure that the poorest sections of the community are adequately housed. Normal commercial suppliers of housing are unwilling to meet this demand because the people concerned cannot afford to pay the full “economic costs” of housing, i.e. it is not usually possible to make a profit from providing housing for the poor. It is much more profitable to provide second homes for the wealthy. Not only does this offend against many people’s ideas of social justice, but the housing problem rebounds against the community, for which it causes extra costs because inadequate housing leads to poor health, disease, crime and a wide range of social problems that become a charge on the taxpayers. Only the State can intervene to improve housing for the poor. It cannot do so simply by holding down rents. It has to promote supply either by setting up State suppliers or by subsidising private suppliers so that supply becomes profitable.

Market Power of Some Large Suppliers

Consumers may not always be as powerful as introductory economic theory suggests. Later we will learn about markets dominated by large firms. If such firms become very powerful, they can influence both supply and demand through controlling the goods allowed into the market and by heavy advertising. Governments of most large marketeconomy nations are often accused of failing to take action to check the sale of tobacco and alcohol – both of which are potentially dangerous to health and society – because of the power of the tobacco and alcohol producing companies. Even more notorious is the extremely powerful “gun lobby” in the USA.

Deficiencies in the Supply of Public Goods

The market economy operates on the principle of self-interest. Consumers wish to maximise their own utility; producers their profit. In most cases this works to the public benefit but not always. If it is in no one’s interest to provide a community or public good, it will not be provided without the intervention of the political machinery of the State. Public sewers, public roads and transport, police and social services, even fire services, fall into this class. The community clearly needs adequate services but left to the market only the wealthy would attempt to purchase their own, and the community as a whole would be subject to the risk of contagious diseases, unchecked crime and fires.

The Case for a Public Sector and its Boundaries

In noting the defects of the market economy as a means of allocating resources we have, in effect, made a case for a public sector within which the State, through its political structures, makes good the gaps and deficiencies of the unregulated market. The State can ensure that there is a minimum standard of housing for those with low incomes, build roads and establish communication systems. It can build sewerage systems and a system of piped, clean water, provide police and fire services and a health and education service to ensure that all who are sick obtain medical care regardless of income and all children achieve a minimum level of education essential for survival in the modern world.

In communities with high living standards the question then arises as to how far State provision should go in the provision of public goods which at some stage tend to become private goods.

Let us take a closer look at two particular, high-profile issues.

Education

Most would accept the need for all to receive a basic education, but this does not necessarily mean that all who wish to do so should have the right to free education to post-graduate level. Since there is evidence that, on average (but not, of course, for all individuals) there is a correlation between income level and length of time spent in fulltime education, then education beyond the minimum represents a personal capital investment and many would argue that such education should be paid for by those who will benefit from it. Counter arguments are that the community benefits from the contribution of its most highly skilled and educated members (e.g. brain surgeons) and should, therefore, pay to obtain the maximum potential from its scarce human resources, and also that those who earn high incomes normally pay the most taxes and thus pay eventually for the education they received. There is no clear right or wrong answer to this debate but you can see that the precise boundaries between the public and private sector in the supply of goods such as education are not clear-cut and the matter is arguable.

Health Care

Another area of public controversy is the provision of health care. The community clearly needs a health service if only to defend itself against dangerous diseases which could quickly become plagues if large numbers of people could not afford treatment. Most people’s ideas of social justice would accept that a person stricken by accident or sickness should receive treatment regardless of income. However, should this mean that all forms of treatment should be available for all regardless of income? Should the diseases of greed and over-indulgence be given the same care as those of poverty and ignorance? If people can afford to pay for additional treatment or for more comfortable treatment, or non-urgent treatment at times that suit them rather than at times that suit a bureaucratic administration, is there any reason why they should not do so? No one passes moral judgement on those who choose to spend their income on exotic holidays rather than a fortnight at a local resort, yet many pass such judgement on those who prefer to pay for a private room when they are in hospital instead of sharing a public ward.

Clearly many of the arguments surrounding health care involve emotionally charged value judgements resulting from past social injustices and history, but there are also serious economic considerations involved. The economist is concerned with the allocation of scarce resources and we have to recognise that resources devoted to health care are scarce. The march of technology and medical science has made possible cures and treatments more widespread. Open heart and transplant surgery require a massive investment in resources but benefit only a relatively few people. The proportion of older people is greater (life Expectancy has increased by approximately 48% since 2004) and the demands they make for health care are proportionally much greater also. Not even the most wealthy and advanced nation can provide all the resources that would be required to give immediate treatment to all those wanting it. Difficult allocation decisions have to be made and are made daily.

On the other hand it can be argued that a private health system which permits scarce resources to be allocated on the basis of ability to pay, or by virtue of employment in a company that provides health insurance as part of its remuneration, is diverting resources from areas of greater personal or social need. One person suffers pain so that a consultant can earn a private income treating a less urgent patient in a private hospital. On the other hand it can be argued that the private health service brings in resources that would otherwise not be available. The consultant is willing to work for a relatively low level of pay from the National Health System because he or she can have the additional income from private patients. Without this, the best surgeons would possibly go to countries where earnings were higher. Private hospitals relieve the public health system of many patients and reduce its need for expensive capital equipment. The debate can again continue with no clear right or wrong.

The basic problem is really one of allocation of scarce resources and the public versus private health service is only part of a much larger economic and social issue which concerns to whom, how and on what basis resources should be allocated for health care. How should the community decide what proportion of available scarce resources should be devoted to the technically brilliant feats of surgery which bring acclaim to surgeons and enable them to attend conferences in exotic countries and how much to the unglamorous, humdrum work of caring for the mentally ill for whom there is no hope of cure and little chance of international laurels for the carer? The unregulated market will not provide an answer, nor will a medical service subject to all the usual human vanities and frailties. The answer must eventually come through the political machinery of the community and the quality of the answer will reflect the health of that machinery.

Similar issues can be applied to virtually every other public sector and public utility service and you should give some thought to the allocation problems inherent in, say, police, fire, water, and housing services.

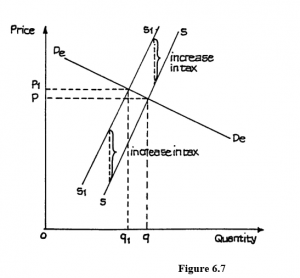

Figure 6.7

PRICE CHANGES AND INDIRECT TAXES AND SUBSIDIES

Effect of Tax on Price

In Study Unit 5 we saw how the supply curve was likely to shift as a result of a change in an indirect tax or subsidy. For the likely effect on market price, however, it is also necessary to take account of the conditions of demand since it is likely that the producer’s efforts to recoup the tax by adding this to the price will leave the quantity demanded in the market unchanged.

Look now at Figure 6.7. Here we show the movement of the supply curve from SS to S1S1 (resulting from the increase in tax) and the demand curve DeDe. The equilibrium price moves up (from Op to Op1) but by an amount less than the increase in tax. The amount supplied to the market falls from Oq to Oq1 and the output/quantity fall is greater than the price rise.

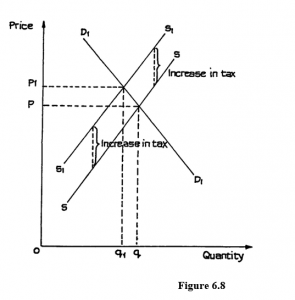

Figure 6.8

Now look at Figure 6.8. Here we have the shift in supply curve SS to S1S1 and a demand curve D1D1. Again we have an increase in equilibrium price (Op to Op1) and a reduction in quantity supplied (Oq to Oq1). This time, however, the reduction in quantity is less than the increase in price.

Why the difference in the two situations? You will have noticed that the curve D1D1 is much steeper than DeDe. This reflects the fact that demand in Figure 6.7 is more price elastic than demand in Figure 6.8. The two illustrations show that the more price elastic the demand for a product is, the smaller will be the market-price increase following an increase in indirect tax, and the greater will be the cutback in supply to the market.

This, after all, is really common sense. Price elasticity indicates the degree of responsiveness of quantity demanded to any change in price.

Subsidies

The effect of a subsidy will be the exact reverse of that of the tax. Instead of the movement of the supply curve from SS to S1S1 there is an increase in supply at all prices, i.e. as from S1S1 to SS, and there will be a reduction in market price, as from Op1 to Op. Such a reduction is likely to have been the main government objective in arranging the subsidy, particularly if the good is a “socially worthy” one such as a basic food in a time of shortage, housing, or a service such as education or health care.

Remember also that the new supply curve need not be exactly parallel to the original before the tax or subsidy change. If the tax or subsidy increases with value, i.e. is an ad valorem tax or subsidy, the gap between the curves will increase as price rises, as illustrated in Figure 5.17.

Government Use of Indirect Taxes

If the government increases indirect tax on goods which are price elastic, it will not receive much extra tax but it will depress demand. If it imposes the tax on goods which are price inelastic, it will not have much effect on output but the government will collect more tax revenue.

If you think back to when we discussed the “income effect” you will realise that the effect of the tax may go further. Suppose there is a general increase in indirect tax on all goods. Some will be demand price inelastic, and their pricing will increase without much reduction in the amount supplied and bought. The buyers are paying more for nearly the same quantity of goods. This means they have less income to spend on other goods – they will have to cut purchases of goods which are price elastic.

The unfortunate producers of price-elastic goods will suffer a double blow. They will suffer a drop in demand from the tax increase and not be able to increase price by anything like the full amount of the tax, and they will suffer a further drop in demand because consumers’ discretionary incomes have fallen.

We have so far assumed that these taxes would be used either to increase government revenues or to reduce consumer demand if the government believed that excess demand was causing inflation. There is, however, another aspect of government policy that is not beginning to appear: this is the control of pollution, which is now recognised as a significant problem.

As indirect tax on expenditure could be used as in instrument to reduce demand, and hence the production or use of something that was believed to be a source of pollution. An example would be an additional tax on petrol to discourage the use of motor vehicles. However, as the demand for petrol is price inelastic then the tax will not have much effect on vehicle use but will reduce consumer incomes available for spending on other goods. One of the main reasons why demand for petrol for car use is price inelastic is because of the lack of satisfactory substitutes. As motor vehicle ownership has increased, the demand for, and supply of, public transport has fallen; and as public transport provision falls and its price rises so even more people are induced to use their own private cars.

We conclude, therefore, that a ‘pollution tax’ on petrol would fail in its objective unless the government also made provision for, and probably subsidised, alternative public transport, at least in urban areas where cars are used for travel to work and for relatively short journeys. If the government also wished to discourage car use for longer journeys it would need to provide alternatives, probably in the form of subsidised public transport. A tax is a very blunt instrument and a government wishing to influence consumer behaviour needs to take many aspects into account. It is not sufficient simply to increase the price of the good whose use it wishes to discourage. Reverting to our general discussion of the effects of taxes on prices, notice that we have not taken into account differing elasticities of supply. This is because supply reactions will take place over a period of time. If suppliers can react by cutting back supply fairly quickly, then there will be further effects on market price. You can examine these for yourself by changing the supply curve to make it more elastic in Figures 6.7 and 6.8.