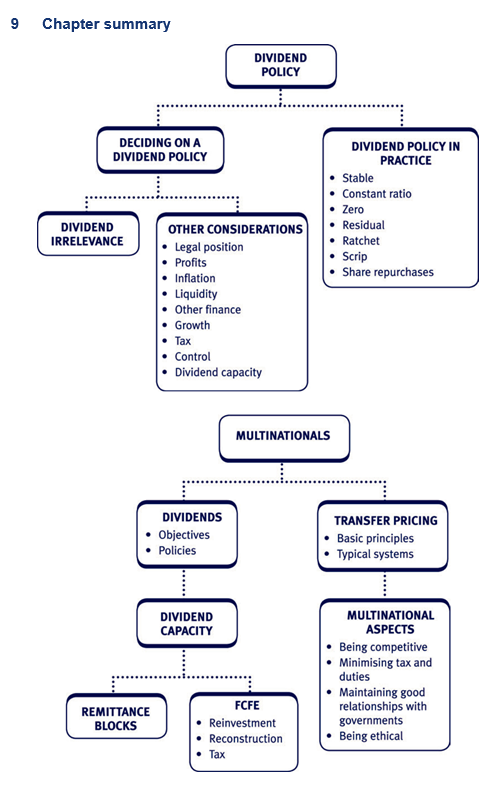

Introduction

In the previous chapters we have seen that the dividend decision is one of three key inter-related decisions that must be made by the financial manager (alongside the investment decision and the financing decision).

This chapter covers the main theoretical and practical considerations when deciding upon a firm’s dividend policy.

2 Dividend policy – The theory

Dividend irrelevancy theory (Modigliani and Miller)

In an efficient market, dividend irrelevancy theory suggests that, provided all retained earnings are invested in positive NPV projects, existing shareholders will be indifferent about the pattern of dividend payouts.

However, practical influences, including market imperfections, mean that changes in dividend policy, particularly reductions in dividends paid, can have an adverse effect on shareholder wealth:

- Reductions in dividend can convey ‘bad news’ to shareholders (dividend signalling).

- Changes in dividend policy, particularly reductions, may conflict with investor liquidity requirements (selling shares to ‘manufacture dividends’ is not a costless alternative to being paid the dividend).

- Changes in dividend policy may upset investor tax planning (e.g. income v capital gain if shares are sold). Companies may have attracted a certain clientele of shareholders precisely because of their preference between income and growth.

As a result, most companies prefer to predetermine dividend policy.

More details on Modigliani and Miller’s theory

The classic view of the irrelevance of the source of equity finance

This view was developed by Modigliani and Miller and may now be regarded as the classic position:

- Their argument is that the source of equity finance is in itself irrelevant.

- Since ultimately it represents a sacrifice of consumption (or other investment opportunities) by the investor at identical risk levels, it makes no difference whether dividends are paid to the investor, or equity is raised as new issues, or profits are simply retained.

- The only differences would arise due to institutional frictional factors, such as issue costs, taxation and so on.

- If both new equity and retained earnings have the same cost then it should be irrelevant, in terms of shareholder wealth, where equity funds come from.

- Provided any cash retained is invested at the shareholders’ required return, a cut in dividend of any size should not adversely affect the investor – the cash lost now is exactly compensated by an increase in the value of their shares. If the funds were actually invested at higher than the expected return for the level of risk, this would in fact increase shareholders’ wealth.

- It theoretically makes no difference whether the new investment is funded by retention of dividend or new equity raised.

- The key issue is thus the investment policy not the dividend policy.

Arguments for the relevance of dividend policy

It was shown above that in theory the level of dividend is irrelevant.

In a perfect capital market it is difficult to challenge the dividend irrelevance position. However, once these assumptions are relaxed, certain practical influences emerge and the arguments need further review.

Dividend signalling

In reality, investors do not have perfect information concerning the future prospects of the company. Many authorities claim, therefore, that the pattern of dividend payments is a key consideration on the part of investors when estimating future performance.

Preference for current income

Many investors require cash dividends to finance current consumption. This does not only apply to individual investors needing cash to live on but also to institutional investors, such as pension funds and insurance companies, who require regular cash outflows to meet day to day outgoings such as pension payments and insurance claims. This implies that many shareholders will prefer companies who pay regular cash dividends and will therefore value their shares more highly.

Resolution of uncertainty

One argument often put forward for high dividend payout is that income in the form of dividend is more secure than income in the form of capital gain. This, therefore, leads investors to place more value on high payout shares (sometimes referred to as the ‘Bird in the Hand’ theory).

Taxation

In many situations income in the form of dividend is taxed in a different way from income in the form of capital gains. This distortion in the personal tax system can have an impact on investors’ preferences.

From the corporate point of view this further complicates the dividend decision, as different groups of shareholders are likely to prefer different payout patterns.

3 Dividend policy – Practical issues

Practical influences on dividend policy

Before developing a particular dividend policy, a company must consider the following:

- legal position

- levels of profitability and free cash flow

- expectations of shareholders

- optimal gearing position – paying a large dividend reduces the value of equity in the firm, so can help a firm move towards its optimal gearing position

- inflation

- control

- tax

- liquidity/cash management in the short and long term

- other sources of finance and the necessary servicing costs. These factors limit the ‘dividend capacity’ of the firm.

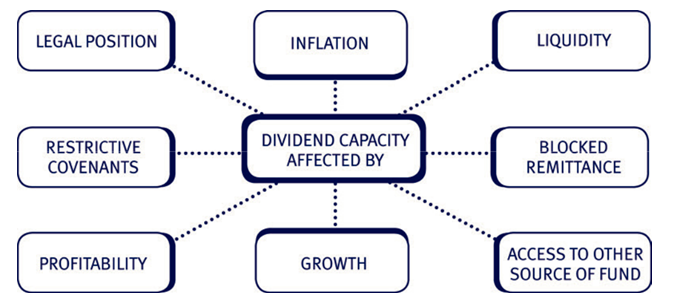

Dividend capacity

This can be simply defined as the ability at any given time of a firm’s ability to pay dividends to its shareholders. This will clearly have a direct impact on a company’s ability to implement its dividend policy (i.e. can the company actually pay the dividend it would like to).

Legally, the firm’s dividend capacity is determined by the amount of accumulated distributable profits.

However, more practically, the dividend capacity can be calculated as the Free Cash Flow to Equity (after reinvestment), since in practice, the level of cash available will be the main driver of how much the firm can afford to pay out.

Legal position in relation to dividends

Many countries will place legal restrictions on the amount of dividend that can be paid out relative to a company’s earnings.

In addition, governments have operated policies of dividend restraint over various periods.

Profitability

Profit is obviously an essential requirement for dividends. All other things being equal, the more stable the profit the greater the proportion that can be safely paid out as dividends. If profits are volatile it is unwise to commit the firm to a higher dividend payout ratio.

Inflation

In periods of inflation, paying out dividends based on historic cost profits can lead to erosion of the operating capacity of the business. For example, insufficient funds may be retained for future asset replacement. Current cost accounting recalculates profit taking into consideration inflation, asset values and capital maintenance. Firms would then ensure that the dividend is limited to the CCA profit.

Growth

Rapidly growing companies commonly pay very low dividends, the bulk of earnings being retained to finance expansion.

Control

The use of internally generated funds does not alter ownership or control.

This can be advantageous particularly in family owned firms.

Liquidity

Sufficient liquid funds need to be available to pay the dividend.

Tax

The personal tax position of investors may put them in a position of preferring either dividend income or capital gains though growing share prices. If the clientele of investors in the company have a clear preference for one or the other, the company should be wary of altering dividend policy and upsetting investors.

Other sources of finance

If a firm has limited access to other sources of funds, retained earnings become a very important source of finance. Dividends will therefore tend to be small. This situation is commonly experienced by unquoted companies that have very limited access to external finance.

4 Real world dividend policies

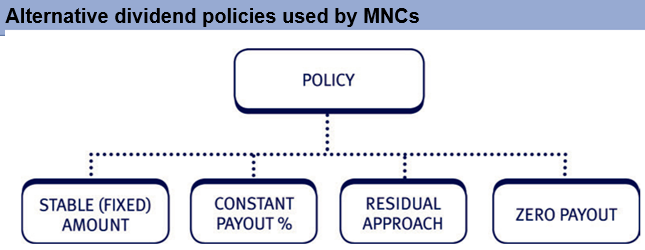

In practice, there are a number of commonly adopted dividend policies:

- stable dividend policy

- constant payout ratio

- zero dividend policy

- residual approach to dividends.

Stable dividend policy

Paying a constant or constantly growing dividend each year:

- offers investors a predictable cash flow

- reduces management opportunities to divert funds to non-profitable activities

- works well for mature firms with stable cash flows.

However, there is a risk that reduced earnings would force a dividend cut with all the associated difficulties.

Constant payout ratio

Paying out a constant proportion of equity earnings:

- maintains a link between earnings, reinvestment rate and dividend flow but

- cash flow is unpredictable for the investor

- gives no indication of management intention or expectation.

Zero dividend policy

All surplus earnings are invested back into the business. Such a policy:

- is common during the growth phase

- should be reflected in increased share price.

When growth opportunities are exhausted (no further positive NPV projects are available):

- cash will start to accumulate

- a new distribution policy will be required.

Residual dividend policy

A dividend is paid only if no further positive NPV projects available. This may be popular for firms:

- in the growth phase

- without easy access to alternative sources of funds. However:

- cash flow is unpredictable for the investor

- gives constantly changing signals regarding management expectations.

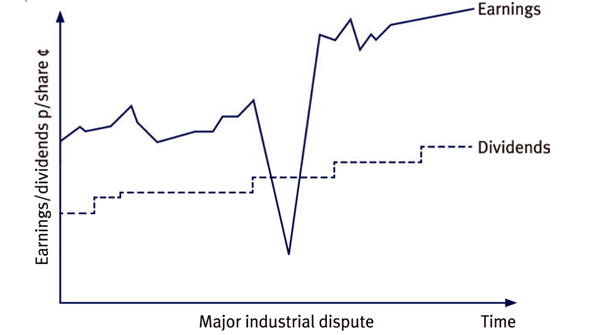

Ratchet patterns

Most firms adopt a variant on the stable dividend policy – a ratchet pattern of payments. This involves paying out a stable, but rising dividend per share:

- Dividends lag behind earnings, but can then be maintained even when earnings fall below the dividend level.

- Avoids ‘bad news’ signals.

- Does not disturb the tax position of investors.

Scrip dividends

A scrip dividend is where a company allows its shareholders to take their dividends in the form of new shares rather than cash.

Do not confuse a scrip issue (which is a bonus issue) with a scrip dividend.

- The advantage to the shareholder of a scrip dividend is that he can painlessly increase his shareholding in the company without having to pay broker’s commissions or stamp duty on a share purchase.

- The advantage to the company is that it does not have to find the cash to pay a dividend and in certain circumstances it can save tax.

Some companies give shareholders the choice between cash and scrip dividends. In such cases the terms of the choice are usually designed so that the shareholder who chooses the scrip sees their wealth increase with a fall in wealth if cash is chosen. Such an arrangement is called ‘an enhanced scrip’. A scrip dividend effectively converts retained profits into permanent share capital.

There can be a number of advantages to ‘paying’ a scrip dividend rather than cash:

- Preservation of cash for re-investment.

- Unless significant, a scrip issue will not dilute the share price.

- More shares reduce the company’s gearing and hence increase its borrowing capacity.

- Shareholders get more shares without incurring transaction costs.

- Shareholders may get a tax advantage if dividends in the form of shares rather than cash.

One major disadvantage in these scrip dividend plans is that shareholders receive no cash with which to pay taxes on the dividends.

Test your understanding 1

A Inc, a listed company, has produced either trading losses or only small profits over the last few years and so has not recently paid any dividends. However following recent management changes and a company restructuring, the company is earning good profits and the directors are looking to formalise the future dividend policy at a forthcoming board meeting.

Particular concerns have been expressed by some directors:

- Director X has referred to the need to provide investors with stability, not reduce dividends and only increase them when it is clear that the increase can be maintained.

- Director Y has commented on the relationship between dividend payments and share price. The director believes that the dividend payout should therefore be as high as possible, with the company borrowing to pay them if necessary.

Required:

Make notes on the relevant matters to raise at the board meeting including comments on the specific concerns raised.

5 Share buyback schemes

If a company wishes to return a large sum of cash to its shareholders, then it might consider a share buyback (or repurchase) rather than a one-off special dividend.

These are schemes through which a company ‘buys back’ its shares from shareholders and cancels them. The company’s Articles of Association must allow it.

It often occurs when the company:

- has no positive NPV projects

- wants to increase the share price [cosmetic exercise]

- wants to reduce the cost of capital by increasing its gearing

- wants to give a positive signal to the market. In the real world, since the directors have more information than the investors about the firm’s financial position, buying the shares gives a signal to investors that the shares currently represent good value for money.

Advantages and disadvantages of a share buyback

Advantages for the company might include:

- Giving flexibility where a firm’s excess cash flows are thought to be only temporary. Management can make the distribution in the form of a share repurchase rather than paying higher cash dividends that cannot be maintained.

- Increasing EPS through a reduction in the number of shares in issue.

- Effective use of surplus funds where growth of business is poor, outlook is poor (i.e. adjusting the equity base to a more appropriate level).

- Buying out dissident shareholders.

- Creation of a ‘market’ where no active market exist for its shares (e.g. if the company is unquoted).

- Altering capital structure to reduce the cost of capital.

- Reducing likelihood of a takeover.

For the shareholders, advantages might include:

- Giving a choice, as they can sell or not sell. With cash dividend shareholders must accept the payment and pay the taxes.

- Saving transaction costs.

But constraints might include:

- Getting approval by general meeting (arguments about the price at which repurchase is to take place).

- The company may pay too high a price for the shares.

- The shareholders may feel they have received too small a price for their shares.

- Premiums paid are set first against share premium and then against distributable profits (if against distributable profits, this will reduce future dividend capacity).

- Might be seen as a failure of the current management/company to make better use of the funds through reinvesting them in the business.

- Shareholders may not be indifferent between dividends and capital gains due to their tax circumstances.

6 Dividend policy in multinational companies

Objectives of a firm’s dividend policy

As discussed earlier, when deciding how much cash to distribute to shareholders, the company directors must keep in mind that the firm’s objective is to maximise shareholder value.

The dividend payout policy should be based on investor preferences for cash dividends now or capital gains in future from enhanced share value resultant from re-investment into projects with a positive NPV.

Many types of multinational company shareholder (for example, institutions such as pension funds and insurance companies) rely on dividends to meet current expenses and any instability in dividends would seriously affect them.

An additional factor for multinationals is that they have more than one dividend policy to consider:

- Dividends to external shareholders.

- Dividends between group companies, facilitating the movement of profits and funds within the group.

Probably the most common policy adopted by multinationals for external shareholders is a variant on stable dividend policy. Most companies go for a stable, but rising, dividend per share:

- Dividends lag behind earnings, but are maintained even when earnings fall below the dividend level, as happens when production is lost for several months during a major industrial dispute. This was referred to as a ‘ratchet’ pattern of dividends.

- This policy has the advantage of not signalling ‘bad news’ to investors. Also if the increases in dividend per share are not too large it should not seriously upset the firm’s clientele of investors by disturbing their tax position.

A policy of a constant payout ratio is seldom used by multinationals because of the tremendous fluctuations in dividend per share that it could bring:

- Many firms, however, might work towards a long-run target payout percentage smoothing out the peaks and troughs each year.

- If sufficiently smoothed the pattern would be not unlike the ratchet pattern demonstrated above.

The residual approach to dividends contains a lot of financial common sense:

- If positive NPV projects are available, they should be adopted, otherwise funds should be returned to shareholders.

- This avoids the unnecessary transaction costs involved in paying shareholders a dividend and then asking for funds from the same shareholders (via a rights issue) to fund a new project.

- The major problem with the residual approach to dividends is that it can lead to large fluctuations in dividends, which could signal ‘bad news’ to investors.

Dividend capacity

Dividend capacity for a multinational company

As for any company, dividend capacity is a major determinant of dividend policy for multinationals. Key factors include:

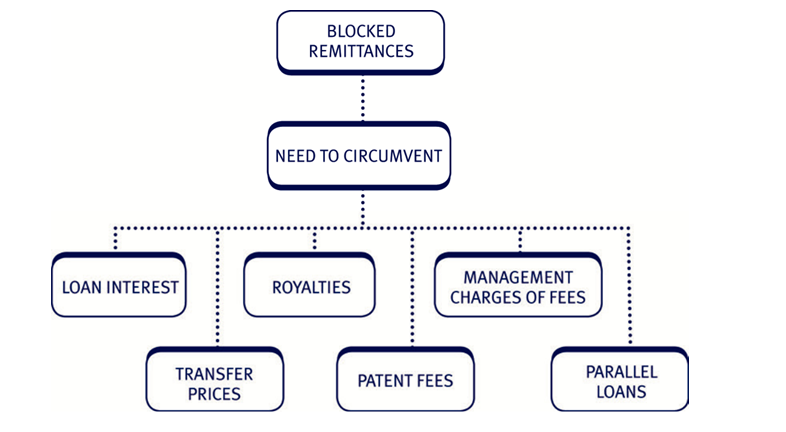

The additional factor that was not discussed earlier is remittance ‘blocking’.

If, once a foreign direct investment has taken place, the government of the host country imposes a restriction on the amount of profit that can be returned to the parent company, this is known as a ‘block on the remittance of dividends’:

- Often done through the imposition of strict exchange controls.

- Limits the amount of centrally remitted funds available to pay dividends to parent company shareholders (i.e. restricts dividend capacity).

How the parent company might try to avoid such a block on remittances

Blocked remittances may be avoided by one of the following methods:

- Increasing transfer prices paid by the foreign subsidiary to the parent company (see below).

- Lending the equivalent of the dividend to the parent company.

- Making payments to the parent company in the form of royalties, payments for patents, and/or management fees and charges.

- Charging the subsidiary company additional head office overheads.

- Parallel loans (currency swaps), whereby the foreign subsidiary lends cash to the subsidiary of another a company requiring funds in the foreign country. In return the parent company would receive the loan of an equivalent amount of cash in the home country from the other subsidiary’s parent company.

The government of the foreign country might try to prevent many of these measures being used.

Free cash flow to equity for a MNC

Free cash flow to equity (FCFE)

- The gross free cash flow to equity of a multinational company can be defined as:

Operating cash flow + dividends from joint ventures – net interest paid – tax.

- To determine the potential dividend capacity of the business, account needs to be taken of any capital re-investment. This is known as the net free cash flow to equity and can be defined as:

Gross free cash flow to equity – capital expenditure +/– disposals/acquisitions + new capital issued.

Example showing FCFE for a MNC

What is the 20X6 net free cash flow to equity (i.e. the potential dividend capacity) for the following business? [All figures are taken from the company’s cash flow statement]

| 20X6 | 20X5 | |

| $m | $m | |

| Capital expenditure | 500 | 400 |

| Acquisition of new subsidiary company | 325 | 0 |

| Disposal of old subsidiary | 250 | 100 |

| Equity dividends paid | 75 | 70 |

| Taxation paid | 275 | 200 |

| Operating cash inflow | 1,000 | 800 |

| Interest paid | 315 | 295 |

| Dividend from joint venture | 150 | 80 |

| New ordinary shares issued | 100 | 100 |

Solution

Gross FCFE = $(1,000 + 150 – 315 – 275) = $560m

Net FCFE [potential dividend capacity] = $(560 – 500 – 325 + 250 + 100)

= $85m

This potential can then be compared to the actual dividend to determine whether there has been an over or under distribution.

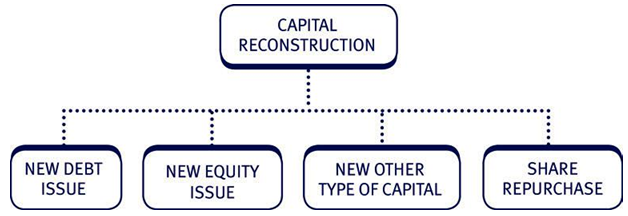

FCFE – Reinvestment and capital reconstruction

Reinvestment strategy

A company’s reinvestment strategy will have two strands:

- Short-term reinvestment – working capital requirements that will come from operating cash flow (for example, an investment in inventory).

- Long-term reinvestment – capital expenditure programmes:

– Generally positive purpose (for example, an expansion plan) and positive expected NPV.

– Sometimes negative purpose (for example, compliance with new legal requirements on emissions in a factory) and negative expected NPV.

Any reinvestment of profits earned will restrict the capacity of a company to pay a dividend.

Management will require to show that the proposed reinvestment strategy will provide a return to shareholders (i.e. increase their wealth) more than an immediate payout in the form of dividends or share repurchase.

In these circumstances, a company may decide to give its shareholders a ‘payout’ using a scrip dividend, preserving the cash in the business for reinvestment and at the same time rewarding its shareholders with a non-cash return in the form of additional shares.

Capital reconstruction programmes

The nature of the capital reconstruction will determine its impact on both current and future free cash flow.

Share repurchase scheme

- Reduces immediate free cash flow to give shareholders an alternative to a straight cash dividend.

- Potentially increases future free cash flows as there will be fewer shares to pay future dividends on but the company may decide to keep the absolute dividend payout the same as before, simply paying out a higher dividend per share than before the repurchase.

New issue of debt for reinvestment purposes (i.e. working capital or capital expenditure)

- Reduces future free cash flow by interest costs and debt repayments.

New issue of debt to pay current cash dividend or share repurchase

- Provides immediate cash to pay dividend or share repurchase.

- Reduces future free cash flow by interest costs and debt repayments.

New issue of equity for reinvestment purposes (i.e. working capital or capital expenditure)

- Increases the number of shares on which dividends may have to be paid in the future but the company may decide to keep the absolute dividend payout the same as before, simply paying out a lower dividend per share than before the new issue.

Other

There may be other forms of capital issue, such as:

- special types of ordinary shares, perhaps with enhanced dividend rights or fixed dividend rights, both payable before ‘normal’ ordinary shares

- preference shares with a first dividend claim on the after tax profit.

Any negative impact that required payments for the type of finance have on free cash flow will reduce the company’s dividend capacity.

8 Transfer pricing

Large diversified groups will be split into numerous smaller profit centres, each preparing accounts for its own sphere of activities and paying tax on its profits. Multinational groups are likely to own individual companies established in different countries throughout the world.

Multinational transfer pricing is the process of deciding on appropriate prices for the goods and services sold intra-group across national borders.

Revision of basic transfer pricing

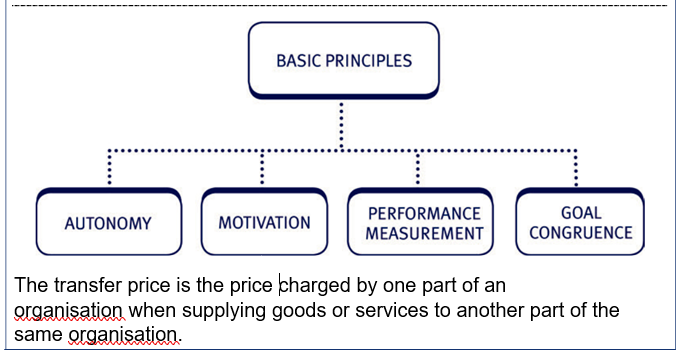

Basic principles

Remember the objectives of a good ‘domestic’ transfer pricing system:

- Maintain divisional autonomy.

- Maintain motivation for managers.

- Assess divisional performance objectively.

- Ensure goal congruence.

The setting of transfer prices is vital for multinational groups.

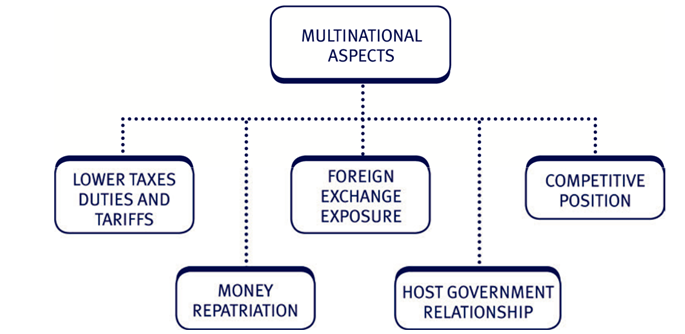

When considering a multinational firm, additional (and in most cases overriding) international transfer pricing objectives are to

- pay lower taxes, duties, and tariffs. A detailed knowledge of different tax regimes is outside the syllabus, but be aware that multinational firms will be keen to transfer profits if possible from high tax countries to low tax ones

- repatriate funds from foreign subsidiary companies to head office

- be less exposed to foreign exchange risks

- build and maintain a better international competitive position

- enable foreign subsidiaries to match or undercut local competitors’ prices

- have good relations with governments in the countries in which the multinational firm operates.

In particular, international transfer pricing requires careful consideration of multiple currency effects and multiple tax and legal regimes.

Illustration 1

Examples in practice of the objectives of international transfer pricing might include:

- reduction of overall corporate income taxes, primarily by manipulating the transfer price to divert taxable income from high tax countries to low tax countries

- minimisation of import duties by setting a low transfer price into a country with import duties will reduce the level of duty paid

- avoidance of exchange controls or other restrictions such as dividend remittance restrictions by setting a low transfer price to the parent company as an alternative to a dividend payment

- improvement of the appearance of the financial performance of a subsidiary by increasing profits through transfer pricing thus helping to:

– satisfy any earnings criteria set by lenders to the subsidiary

– make the acquisition of a new loan easier.

Transfer pricing (especially international transfer pricing) is not simply buying and selling products between divisions. The term is also used to cover, inter alia:

- head office general management charges to subsidiaries for various services

- specific charges made to subsidiaries by, for example, head office human resource or information technology functions

- royalty payments

– between parent company and subsidiaries

– among subsidiaries.

- interest rate on borrowings between group companies.

The basics of transfer pricing

A general rule for transfer pricing

Transfer price per unit = Standard variable cost in the producing division plus the opportunity cost to the company as a whole of supplying the unit internally.

The opportunity cost will be either the contribution forgone by selling one unit internally rather than externally, or the contribution forgone by not using the same facilities in the producing division for their next best alternative use.

The dividend decision

The application of this general rule means that the transfer price equals:

- the standard variable cost of the producing division, if there is no outside market for the units manufactured and no alternative use for the facilities in that division

- the market price, if there is an outside market for the units manufactured in the producing division and no alternative more profitable use for the facilities in that division.

Transfer pricing systems

A transfer pricing system should:

- be reasonably easy to operate and to understand

- be flexible in terms of a changing organisation structure

- allow divisional autonomy to be maintained, since continued autonomy should motivate divisional managers to give their best performance

- allow divisional performance to be assessed objectively

- ensure that divisional managers make decisions that are in the best interests both of the divisions and of the whole company.

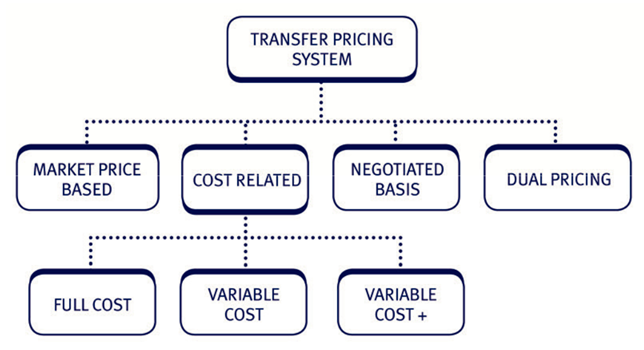

There are broadly three types of transfer prices:

- Market-based prices.

- Cost-related prices.

- Negotiated prices and dual prices.

Application to multinational companies

Choice of transfer price basis for the multinational company

Basis

Market based

Full cost

Variable cost

Negotiated

Comments

- Encouraged by tax and customs authorities in both multinational company and local subsidiary jurisdictions.

- The profit split between the group companies is fair and therefore the authorities in each country receive their appropriate share of corporate tax and duties.

- Prices for the same goods in different countries could vary significantly.

- Exchange rate changes could have significant impact.

- Local taxes could have significant impact.

- Strategically, subsidiary will want to set its prices in accordance with local supply and demand conditions.

- Acceptable to tax and customs authorities in both multinational company and local subsidiary jurisdictions.

- The authorities in each country receive their appropriate share of corporate tax and duties as the transfer price approximates to the ‘correct’ cost of the goods.

- Unacceptable to tax and customs authorities in the supplying company’s jurisdiction.

- All profits allocated to the receiving company and thus no corporate tax payable by supplying company.

- Could result in sub-optimal decision as no advantage taken of different corporate tax rates and duties.

Illustration of a tax minimising strategy

If the taxation on corporate profits is:

- 35% in Wyland

- 25% in Exland.

A multinational company operating in both of these countries may try to ‘manipulate’ its results so that the majority of the profit is made by its subsidiary/division in Exland thereby saving corporate tax.

The aim is to minimise profits in Wyland and maximise profit in Exland. It could do this via:

- increasing or decreasing transfer prices between the subsidiaries/divisions as appropriate

- invoice services provided by the Exland subsidiary/division to the Wyland subsidiary/division.

This objective is frustrated in many countries whose governments require that transfer prices are set on an arm’s length basis [i.e. using the prevailing market price]. The principle is still useful however as a broad objective and particularly valuable when transferring goods for which no external market price exists or when operating in countries without an arm’s length transfer price requirement.

Alternatively many multinational businesses sited in high tax jurisdictions create marketing/promotional/distribution subsidiaries in low tax jurisdictions and transfer products to them at low transfer prices. Overall corporate tax will be reduced, as the profit from selling these products to the final customer will be taxed in the lower jurisdiction.

If transfer prices are set on the basis of minimising tax, this can have consequences for the whole company:

- Autonomy will be compromised if the parent company fixes transfer prices throughout the group to minimise total tax.

- This can have adverse motivational consequences.

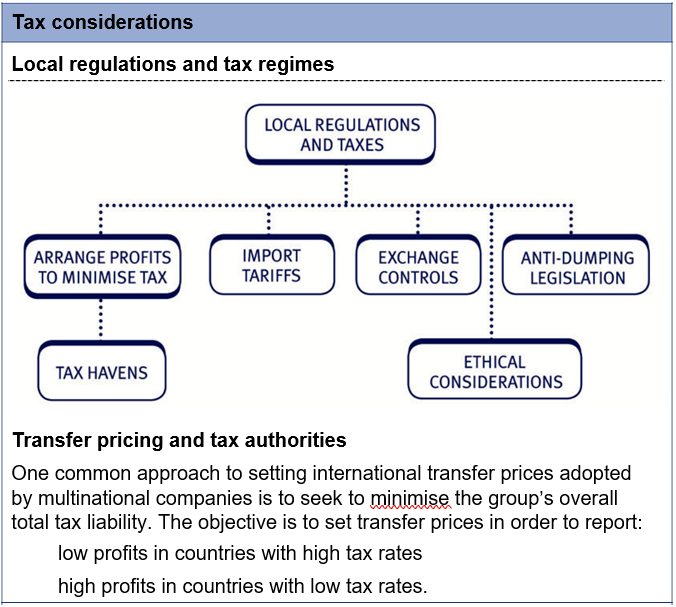

Tax havens, import tariffs and local regulations The use of tax havens

A tax haven is a country that has a series of unique characteristics, the primary one being relatively low tax compared to other countries. Bank secrecy and strict privacy laws are also other common features of tax havens.

There are many tax havens throughout the world. Well-known examples are:

- Cayman Islands

- Luxembourg

- Liechtenstein

- Bahamas

- Jersey (the Channel Islands).

From the perspective of a multinational company tax havens may provide opportunities to reduce corporate taxes by the quite legal use of subsidiaries in offshore tax havens like the Cayman Islands. Where tax regimes differ around the globe organisations can make use of differing tax rules to keep a larger proportion of their profits.

A defining feature of the tax haven is that normally little production takes place but many organisations are registered there. Many companies seek to lower their taxes by, for example, setting up foreign units and using internal lending so that profits are taken primarily in tax havens and costs are incurred in high tax countries.

Inevitably tax authorities in higher tax countries have sought to close tax loopholes, and potentially such changes could result in a heavily increased tax burden for multinationals and hence represents a significant risk to their post-tax earnings. However, advantages still exist. A tax haven will be most attractive with the following criteria:

- Low rate of corporation tax.

- Low withholding tax on dividends paid to overseas holding companies.

- Comprehensive tax treaties with other countries.

- Stable economy with low political risk.

- Lack of exchange controls.

- Good communications with the rest of the world.

- Developed legal framework so that rights can be safeguarded.

Import tariffs

An import tariff is a schedule of duties imposed by a country on imported goods. The tariff can be levied on a percentage of the value of the import, or as an amount per unit of import.

For example, if the government of Zedland imposes an import tariff of 10% on the value of all goods imported, a multinational company with a subsidiary/division in Zedland that imports goods from another subsidiary in another country may decide to minimise costs by minimising the transfer price.

That decision might, however, conflict with the objective of minimising corporate taxation if the subsidiary then sold the goods to the final customer and corporate taxation rate in Zedland was very high.

Local regulations

There are other potential local rules and regulations that will impact on the transfer pricing policy of a multinational company.

Exchange controls

Foreign exchange controls are various forms of controls imposed by a government on the purchase/sale of foreign currencies by residents or on the purchase/sale of local currency by non-residents. A common exchange control is a restriction on the amount of currency that may be imported or exported.

Profits made and cash flows earned in a foreign country are of no value to a multinational group if they cannot be repatriated to the home country for distribution to shareholders. Under exchange controls, capital invested into a country may often be repatriated, whereas remittance of the profits is strictly limited.

Charging management fees, royalties, fees for research and development, technical know-how and so on, will impact upon the profitability in a subsidiary abroad. Provided that even those fees and so on can be remitted, and do not become restricted also by the exchange controls, this is a way of releasing funds from a country, which has such controls.

Most governments are naturally well aware of these possibilities and respond by limiting repatriations in general. For example, a proportion of profit made may have to be retained and reinvested in the host country. Such ‘blocked funds’ may even have to be invested in government bonds, the cash from which may then be sent to the group but only upon maturity.

Anti-dumping legislation

‘Dumping’ is the practice of selling goods/services in an overseas/foreign market at a price lower than the price or cost in the home market. It might be without motive or it might have an economic purpose such as trying to put competitors out of business. Anti-dumping legislation is designed to minimise the impact of this practice.

For example, many governments take action to protect domestic industries by preventing multinational companies from transferring goods cheaply into their countries. Forcing the use of market price based transfer pricing can do this.

Ethical issues in transfer pricing

There are a number of potential ethical issues for the multinational company to consider when formulating its transfer pricing strategy:

- Social responsibility, reducing amounts paid in customs duties and tax.

- Bypassing a country’s financial regulation via remittance of dividends.

- Not operating as a ‘responsible citizen’ in foreign country.

- Reputational loss.

- Bad publicity.

- Tax evasion.

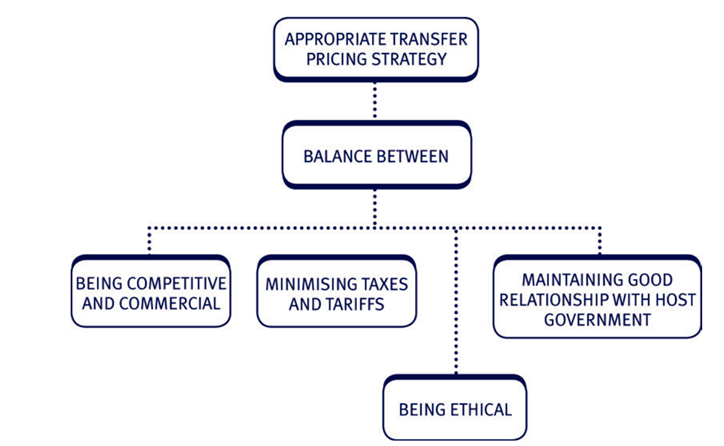

Summary – Deciding on a transfer pricing strategy

Comprehensive example

Colsan plc [‘Colsan’] is a UK-based multinational company with two overseas subsidiaries. Colsan wishes to minimise its global tax bill, and part of its tax strategy is to try to take advantage of opportunities provided by transfer pricing.

| Colsan has subsidiaries in Fraland and Serland | |||

| Taxation and excise duty rates | UK | Fraland | Serland |

| Corporate tax on profits | 30% | 45% | 20% |

| Withholding tax on dividends | – | 10% | – |

| Import tariffs on all goods (not tax | |||

| allowable) | – | – | 5% |

The Fraland subsidiary produces 100,000 sofa frames per annum, which are then sent to Serland for the upholstery to be added, and the furniture completed. The frames are sold to the Serland subsidiary at a transfer price equal to variable cost (which is £50) plus 50%. Annual fixed costs in Fraland are £1.5m.

The Serland subsidiary incurs additional variable costs of £72 per unit and sells the completed furniture for £200 per unit in Serland. Annual fixed costs in Serland are £1.7m.

All transactions between the companies are in £ sterling. Each year, the Fraland subsidiary remits 60% of its profit after tax and the Serland subsidiary remits 100% of its profit after tax to Colsan.

Required:

If Colsan instructs the Fraland subsidiary to sell the frames to the Serland subsidiary at full cost

- Determine the potential effect of this on the group tax and tariff payments.

- Outline the consequences of this strategy.

Assume that bilateral tax agreements exist which allow Fraland and Serland tax paid to be credited against Colsan’s UK tax liability.

| Potential effect 1 [under the current | Fraland | Serland | ||

| scheme] | £000 | £000 | ||

| Sales | 7,500 | 20,000 | ||

| Variable costs | (5,000) | (7,200) | ||

| Cost from Fraland | – | (7,500) | ||

| Fixed costs | (1,500) | (1,700) | ||

| Profit before tax | 1,000 | 3,600 | ||

| Local corporate tax [45% in Fraland, 20% in | ||||

| Serland] | (450) | (720) | ||

| Profit after local corporate tax | 550 | 2,880 | ||

| Import tariff [5% in Serland] | – | (375) |

| Gross remittance to UK [60% before | ||

| withholding tax in Fraland, 100% in Serland] | 330 | 2,505 |

| With-holding tax [10% in Fraland] | (33) | – |

| With-holding tax [10% in Fraland] | (33) | – |

| Net remitted to UK | 297 | 2,505 |

| Retained locally | 220 | 0 |

| UK corporate tax: | ||

| Taxable profit | 1,000 | 3,600 |

| UK corporate tax @ 30% | 300 | 1,080 |

| Less: local corporate tax [allowed under bi- | ||

| lateral agreement] | (300) | (720) |

| Additional UK corporate tax payable | 0 | 360 |

| Sales | 6,500 | 20,000 |

| Variable costs | (5,000) | (7,200) |

| Cost from Fraland | – | (6,500) |

| Fixed costs | (1,500) | (1,700) |

| Profit before tax | 0 | 4,600 |

| Local corporate tax [45% in Fraland, 20% in | ||

| Serland] | 0 | (920) |

| Profit after local corporate tax | 0 | 3,680 |

| Import tariff [5% in Serland] | – | (325) |

| Gross remittance to UK [60% before | ||

| withholding tax in Fraland, 100% in Serland] | 0 | 3,355 |

| With-holding tax [10% in Fraland] | 0 | – |

| Net remitted to UK | 0 | 3,355 |

| Retained locally | 0 | 0 |

| UK corporate tax: | ||

| Taxable profit | 0 | 4,600 |

| UK corporate tax @ 30% | 0 | 1,380 |

| Less: local corporate tax | ||

| [allowed under bi-lateral agreement] | 0 | (920) |

| Additional UK corporate tax payable | 0 | 460 |

| Summary of potential | Under the | Under the | Difference | |||

| effects | current | proposed | ||||

| scheme | scheme | |||||

| Net amount remitted to | £000 | £000 | £000 | |||

| UK | 2,802 | 3,355 | 553 | |||

| Retained locally in | ||||||

| Fraland | 220 | 0 | (220) | |||

| Taxes payable: | ||||||

| In UK [additional tax] | 360 | 460 | (100) | |||

| In Fraland | 483 | 0 | 483 | |||

| In Serland | 1,095 | 1,245 | (150) | |||

| Total taxes payable | 1,938 | 1,705 | 233 | |||

| The proposed new scheme may be unacceptable to: | ||||||

| | The tax authorities in Fraland, where £483,000 in corporate taxes | |||||

| would be lost. The tax authorities might insist on an arms-length | ||||||

| transfer price for transfers between Fraland and Serland. | ||||||

| | The subsidiary in Fraland, which would no longer make a profit, or | |||||

| have retentions available for future investment in Fraland. | ||||||

| Dependent on how performance in Fraland was evaluated, this | ||||||

| might adversely affect rewards and motivation for the employees in | ||||||

| Fraland. | ||||||

Test your understanding 1

Notes would need to cover:

Theoretical position on dividends

Provided a company invests in positive NPV projects, the pattern of dividend payments is not relevant to an investor. The company should therefore use the funds available to invest in all positive NPV opportunities and any remaining funds should be distributed as dividends. Dividends are a residual decision.

Information content

In practice however, investors treat the level of dividends as a signal about the financial wellbeing of the company, and believe that high dividends signal confidence about the future.

This contrasts directly with the theory which would suggest a confident company would be retaining dividends to invest in all the positive NPV projects.

Clientele effect

Certain types of investor have a preference for certain types of income, and constantly changing the level of dividend payout will make it difficult for investors to plan their cash and tax positions.

Liquidity

Whilst it is theoretically possible for a firm to borrow to pay dividends, taking out loan finance will alter the gearing level of the firm, which itself will be the subject of policy and cannot be altered arbitrarily.

Cost of finance

If the firm needs funds for future investments, retained earnings are the cheapest source of funds available.

Policy

A suitable policy would therefore be one that:

- leaves sufficient funds for investment and avoids the need to incur transaction costs raising funds in the near future

- has a fairly constant dividend pattern.

Director X

This is the policy many companies do adopt in practice. The problem is that it ignores the availability of funds, and the investment projects that may require them.

Director Y

Director Y is correct that the value of a share is, in part, dependent on the dividend stream. In theory, as mentioned above, it should not matter if a dividend is missed, provided the funds are invested in positive NPV projects. However, it is true that in practice, if shareholders are unhappy about the cut, and sell their shares the price fall.