The financing decision

Introduction

As discussed at the beginning of Chapter 2: Investment appraisal, the financial manager often has to decide what type of finance to raise in order to fund the investment in a new project i.e. there is a very close link between the investment decision and the financing decision.

This chapter starts by looking at the ‘financial system’ and then it covers the key practical and theoretical considerations that influence the basic long-term financing decision i.e. should debt or equity finance be used?

Then, the chapter explains the main features of the key debt and equity financing sources, incorporating both domestic and international financing options.

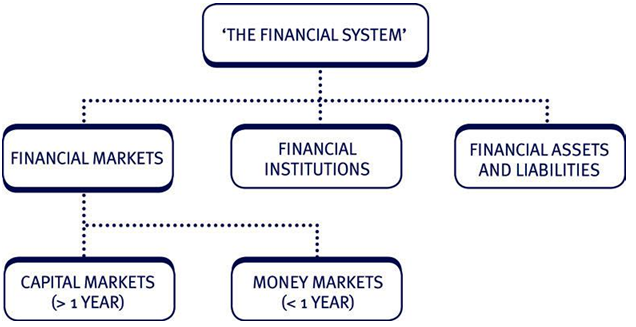

2 The financial system

It is important to understand the financial system before we look at specific financing options:

Collectively the financial system does the following:

- Channels funds from lenders to borrowers.

- Provides a mechanism for payments – e.g. direct debits, cheque clearing system.

- Creates liquidity and money – e.g. banks create money through increasing their lending.

- Provides financial services such as insurance and pensions.

Offers facilities to manage investment portfolios – e.g. to hedge risk.

Details of the financial system

The financial system

‘The financial system’ is an umbrella term covering the following:

- Financial markets – e.g. stock exchanges, money markets.

- Financial institutions – e.g. banks, building societies, insurance companies and pension funds.

- Financial assets and liabilities – e.g. mortgages, bonds, bills and equity shares.

Financial markets

The financial markets can be divided into different types, depending on the products being issued/bought/sold:

- Capital markets which consist of stock-markets for shares and bond markets.

- Money markets, which provide short-term (< 1 year) debt financing and investment.

- Commodity markets, which facilitate the trading of commodities (e.g. oil, metals and agricultural produce).

- Derivatives markets, which provide instruments for the management of financial risk, such as options and futures contracts.

- Insurance markets, which facilitate the redistribution of various risks.

- Foreign exchange markets, which facilitate the trading of foreign exchange.

Within each sector of the economy (households, firms and governmental organisations) there are times when there are cash surpluses and times when there are deficits.

- In the case of surpluses the party concerned will seek to invest/deposit/lend funds to earn an economic return.

- In the case of deficits the party will seek to borrow funds to manage their liquidity position.

In our syllabus, we focus on the long-term financing options. Short-term financing options (e.g. money market instruments) are not normally used to finance long-term capital investment projects such as the ones appraised in the previous chapters.

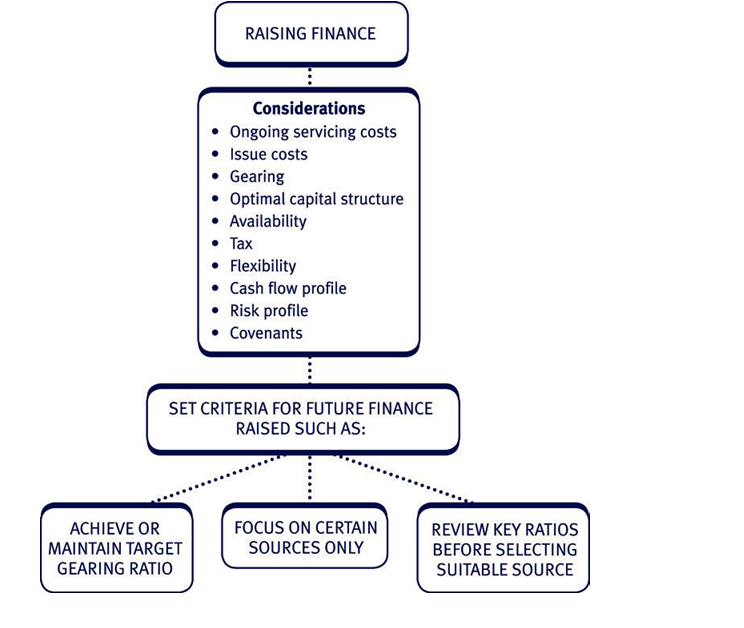

Practical considerations

The following diagram summarises the main practical factors that must be considered when choosing between debt and equity finance.

More detail on practical considerations

Ongoing servicing costs

Debt is usually cheaper than equity due to lower risk faced by the providers of finance and the tax relief possible on interest payments. However, some debt, such as an unsecured overdraft, may be more expensive than equity.

Issue costs

The costs of raising debt are usually lower than those for issuing new shares (e.g. prospectus costs, stock exchange fees, stamp duty).

Gearing

Debt and preference shares give rise to fixed payments that must be made before ordinary shareholder dividends can be paid. These methods of finance thus increase shareholder risk.

Optimal capital structure

This was previously covered in Financial Management (FM), and is discussed further below. You will remember that firms have to make a trade-off between the benefits of cheap debt finance on the one hand and the costs associated with high levels of gearing (such as the risk of bankruptcy) on the other. If the correct balance can be achieved, the cost of finance will fall to a minimum point, maximising NPVs and hence the value of the firm.

Availability of sources of finance

Not all firms have the luxury of selecting a capital structure to maximise firm value. More basic concerns, such as persuading the bank to release further funds, or the current shareholders to make a further investment, may override thoughts about capital structure.

Tax position

The tax benefits of debt only remain available whilst the firm is in a tax paying position.

Flexibility

Some firms operating in high risk industries use mainly equity finance to gain the flexibility not to have to pay dividends should returns fall.

Cash flow profile

Cash flow forecasts are central to financing decisions – e.g. ensuring that two sources of finance do not mature at the same time.

Risk profile

Business failure can have a far greater impact on directors than on a well-diversified investor. It may be argued that directors have a natural tendency to be cautious about borrowing.

Covenants

There may be restrictions imposed on the level of gearing, either by the company’s Articles of Association (the internal regulations that govern the way the company must be run), or by previous loan agreements.

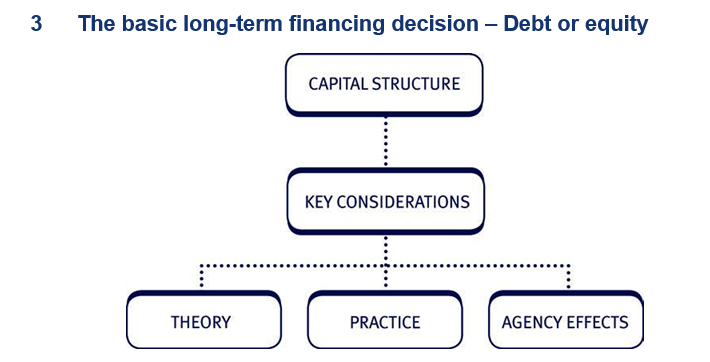

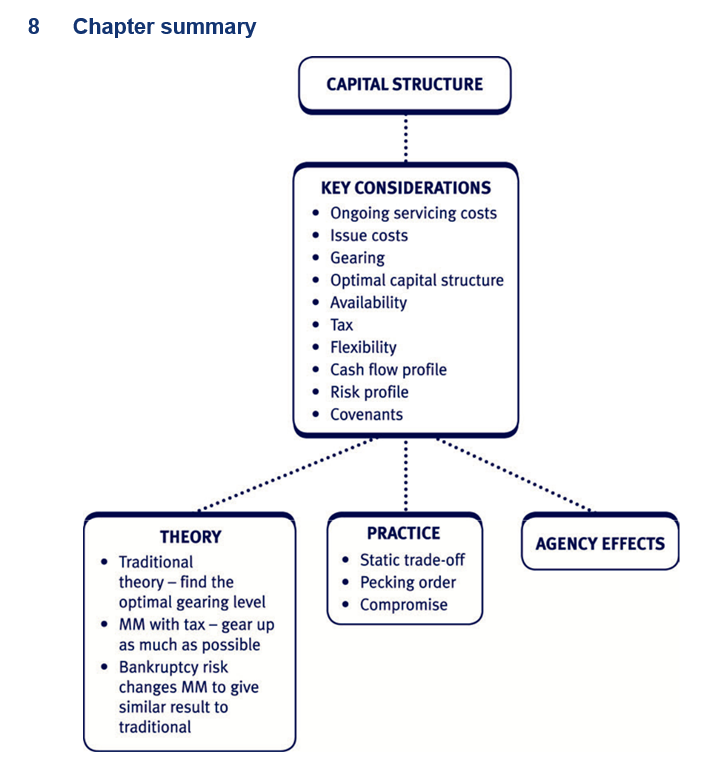

Theoretical considerations

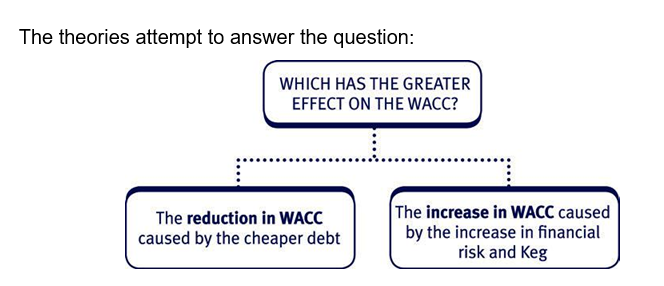

The main capital structure theories assess the way in which a change in gearing/capital structure impacts on the firm’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

Note: Although the detailed calculation of WACC is not covered until later in this Text (Chapter 6: The weighted average cost of capital), you will be aware from your previous studies that the WACC is a vitally important concept in financial management. If the financial manager can find a way of reducing the WACC, projects will have higher NPVs and consequently the wealth of the firm’s shareholders will be increased.

The theories consider the relative sizes of the following two opposing forces:

First, debt is (usually) cheaper than equity:

- Lower risk.

- Tax relief on interest.

so we might expect that increasing proportion of debt finance would reduce WACC.

BUT:

Second, increasing levels of debt makes equity more risky:

- Fixed commitment paid before equity – finance risk.

so increasing gearing (proportion of finance in the form of debt) increases the cost of equity and that would increase WACC.

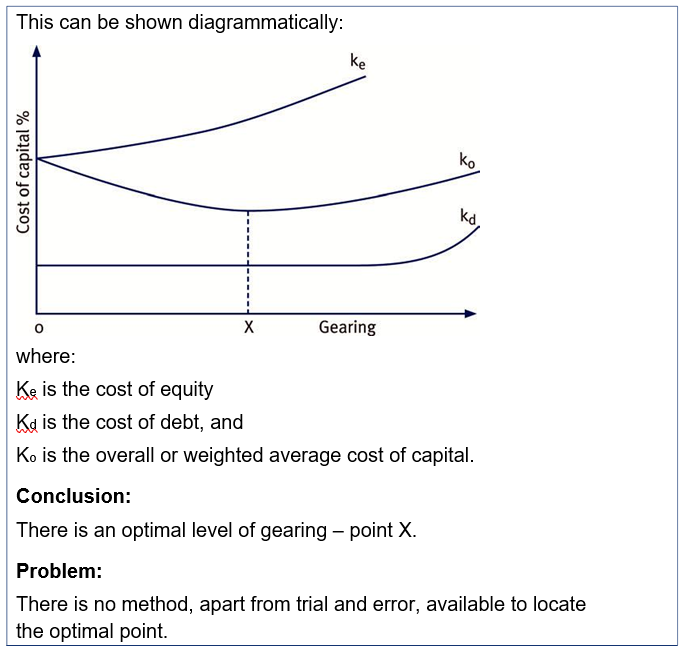

The traditional view

Also known as the intuitive view, the traditional view has no theoretical basis but common sense. It concludes that a firm should have an optimal level of gearing, where WACC is minimised, BUT it does not tell us where that optimal point is. The only way of finding the optimal point is by trial and error.

The traditional view explained

At low levels of gearing:

Equity holders see risk increases as marginal as gearing rises, so the cheapness of debt issue dominates resulting in a lower WACC.

At higher levels of gearing:

Equity holders become increasingly concerned with the increased volatility of their returns (debt interest paid first). This dominates the cheapness of the extra debt so the WACC starts to rise as gearing increases.

At very high levels of gearing:

Serious bankruptcy risk worries equity and debt holders alike so both Ke and Kd rise with increased gearing, resulting in the WACC rising further.

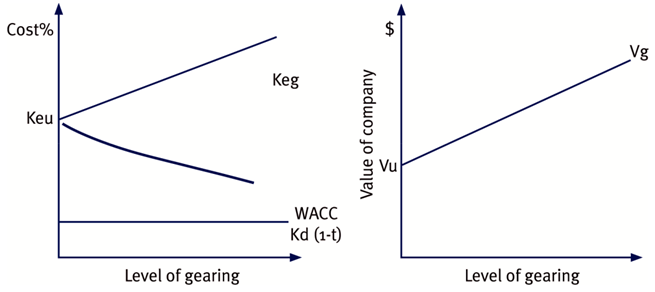

Modigliani and Miller’s theory (with tax)

Modigliani and Miller’s ‘with tax theory’ concluded that because of the tax advantages of issuing debt finance (tax relief on debt interest) firms should increase their gearing as much as possible. The theory is based on assumptions such as perfect capital markets.

Modigliani and Miller’s theory explained

The starting point for the theory is that:

- as investors are rational, the required return of equity is directly linked to the increase in gearing – i.e. as gearing increases, Ke increases in direct proportion.

However, this is adjusted to reflect that:

- debt interest is tax deductible so the overall cost of debt to the company is lower than in MM – no tax

- lower debt costs imply less volatility in returns for the same level of gearing, giving smaller increases in Ke

- the increase in Ke does not offset the benefit of the cheaper debt finance and therefore the WACC falls as gearing is increased.

Conclusion:

Gearing up reduces the WACC, and the optimal capital structure is 99.9% gearing.

This is demonstrated in the following diagrams:

In practice firms are rarely found with the very high levels of gearing as advocated by Modigliani and Miller. This is because of:

- bankruptcy risk

- agency costs

- tax exhaustion

- the impact on borrowing/debt capacity

- differences in risk tolerance levels between shareholders and directors

- restrictions in the Articles of Association

- increases in the cost of borrowing as gearing increases.

As a result, despite the theories, gearing levels in real firms tend to be based on more practical considerations.

Key practical arguments against M+M

Bankruptcy risk

As gearing increases so does the possibility of bankruptcy. If shareholders become concerned, this will reduce the share price and increase the WACC of the company.

Agency costs: restrictive conditions

In order to safeguard their investments lenders/debentures holders often impose restrictive conditions in the loan agreements that constrains management’s freedom of action.

E.g. restrictions:

- on the level of dividends

- on the level of additional debt that can be raised

- on management from disposing of any major fixed assets without the debenture holders’ agreement.

Tax exhaustion

After a certain level of gearing companies will discover that they have no tax liability left against which to offset interest charges.

Kd(1 – t) simply becomes Kd.

Borrowing/debt capacity

High levels of gearing are unusual because companies run out of suitable assets to offer as security against loans. Companies with assets, which have an active second-hand market, and low levels of depreciation such as property companies, have a high borrowing capacity.

Difference risk tolerance levels between shareholders and directors

Business failure can have a far greater impact on directors than on a well-diversified investor. It may be argued that directors have a natural tendency to be cautious about borrowing.

Test your understanding 1

X Co, an unquoted manufacturing company, has been experiencing a growth in demand, and this trend is expected to continue. In order to cope with the growth in demand, the company needs to buy further machinery and this is expected to cost 30% of the current company value.

In the past, a high proportion of earnings has been distributed by way of dividends so few cash reserves are available. 51% of the shares in X Co are still owned by the founding family.

A decision must now be taken about how to raise the funds. The firm has already raised some loan finance and this is secured against the company land and buildings.

Required:

Suggest the issues that should be considered by the board in determining whether debt would be an appropriate source of finance.

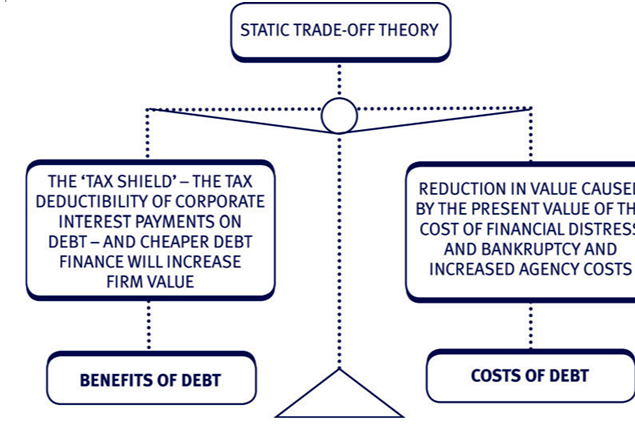

Real world issues – Static trade-off theory Static trade-off theory

It is possible to revise M and M’s theory to incorporate bankruptcy risk and so to arrive at the same conclusion as the traditional theory of gearing – i.e. that an optimal gearing level exists.

Given this, firms will strive to reach the optimum level by means of a trade-off.

Static trade -off theory argues that firms in a stable (static) position will adjust their current level of gearing to achieve a target level:

Above target debt ratio the value of the firm is not optimal:

- Financial distress and agency costs exceed the benefits of debt.

- Firms decrease their debt levels.

Below the target debt ratio can still increase the value of the firm because:

- marginal value of the benefits of debt are still greater than the costs associated with the use of debt

- firms increase their debt.

NB: Research suggests that this theory is not backed up by empirical evidence.

Real world issues – Pecking order theory Pecking order theory

Pecking order theory tries to explain why firms do not behave the way the static trade-off model would predict. It states that firms have a preferred hierarchy for financing decisions:

The implications for investment are that:

- the value of a project depends on how it is financed

- some projects will be undertaken only if funded internally or with relatively safe debt but not if financed with risky debt or equity

- companies with less cash and higher gearing will be more prone to under-invest.

If a firm follows the pecking order:

- its gearing ratio results from a series of incremental decisions, not an attempt to reach a target

– High cash flow Þ Gearing ratio decreases

– Low cash flow Þ Gearing ratio increases

- there may be good and bad times to issue equity depending on the degree of information asymmetry.

Real world issues – A compromise approach A compromise approach

The different theories can be reconciled to encourage firms to make the correct financing decisions:

- Select a long run target gearing ratio.

- Whilst far from target, decisions should be governed by static trade-off theory.

- When close to target, pecking order theory will dictate source of funds.

More on pecking order v static trade off

Pecking order theory was developed to suggest a reason for this observed inconsistency in practice between the static trade-off model and what companies actually appear to do.

Issue costs

Internally generated funds have the lowest issue costs, debt moderate issue costs and equity the highest. Firms issue as much as they can from internally generated funds first then move on to debt and finally equity.

Asymmetric information

Myers has suggested asymmetric information as an explanation for the heavy reliance on retentions. This may be a situation where managers, because of their access to more information about the firm, know that the value of the shares is greater than the current market value based on the weak and semi-strong market information.

In the case of a new project, managers forecast maybe higher and more realistic than that of the market. If new shares were issued in this situation there is a possibility that they would be issued at too low a price, thus transferring wealth from existing shareholders to new shareholders. In these circumstances there might be a natural preference for internally generated funds over new issues. If additional funds are required over and above internally generated funds, then debt would be the next alternative.

If management is against making equity issues when in possession of favourable inside information, market participants might assume that management would be more likely to favour new issues when they are in possession of unfavourable inside information. This leads to the suggestion that new issues might be regarded as a signal of bad news! Managers may therefore wish to rely primarily on internally generated funds supplemented by borrowing, with issues of new equity as a last resort.

Myers and Majluf (1984) demonstrated that with asymmetric information, equity issues are interpreted by the market as bad news, since managers are only motivated to make equity issues when shares are overpriced.

Bennett Stewart (1990) puts it differently: ‘Raising equity conveys doubt. Investors suspect that management is attempting to shore up the firm’s financial resources for rough times ahead by selling over-valued shares.’

Asquith and Mullins (1983) empirically observed that announcements of new equity issues are greeted by sharp declines in stock prices. Thus, equity issues are comparatively rare among large established companies.

Real world issues – Gearing drift

Dealing with ‘gearing drift’

Profitable companies will tend to find that their gearing level gradually reduces over time as accumulated profits help to increase the value of equity. This is known as ‘gearing drift’.

Gearing drift can cause a firm to move away from its optimal gearing position. The firm might have to occasionally increase gearing (by issuing debt, or paying a large dividend or buying back shares) to return to its optimal gearing position.

Real world issues – Signalling to investors Signalling to investors

In a perfect capital market, investors fully understand the reasons why a firm chooses a particular source of finance.

However, in the real world it is important that the firm considers the signalling effect of raising new finance. Generally, it is thought that raising new finance gives a positive signal to the market: the firm is showing that it is confident that it has identified attractive new projects and that it will be able to afford to service the new finance in the future.

Investors and analysts may well assess the impact of the new finance on a firm’s statement of profit or loss and balance sheet (statement of financial position) in order to help them assess the likely success of the firm after the new finance has been raised.

Consider the following example, which shows the impact on key financial ratios of using different sources of finance:

A company is considering a number of funding options for a new project. The new project may be funded by $10m of equity or debt. Below are the financial statements under each option.

Statement of financial position (Balance sheet) extract

| Equity finance | Debt finance | |

| Long term liabilities | $m | $m |

| Debentures (10%) | 0.0 | 10.0 |

| Capital | –––– | –––– |

| Share capital (50¢) | 11.0 | 3.5 |

| Share premium | 4.0 | 1.5 |

| Reserves | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| –––– | –––– | |

| 20.0 | 10.0 | |

| –––– | –––– | |

| Statement of profit or loss extract | ||

| $m | ||

| Revenue | 100.0 | |

| Gross profit | 20.0 | |

| Less expenses (excluding finance charges) | (15.0) | |

| ––––– | ||

| Operating profit | 5.0 | |

| ––––– | ||

Corporation tax is charged at 30%.

Required:

- Calculate ROCE and return on equity (ROE) and compare the financial performance of the company under the two funding options.

- What is the impact on the company’s performance of financing by debt rather than equity?

| Solution | ||||

| Equity finance | Debt finance | |||

| (a) Return on capital | = $5m/$20m × | = $5m/$20m × | ||

| employed | ||||

| 100 | 100 | |||

| Working | = 25% | = 25% | ||

| $m | $m | |||

| PBFC&T | 5.0 | 5.0 | ||

| Finance charges | 0.0 | (1.0) | ||

| –––– | –––– | |||

| PBT | 5.0 | 4.0 | ||

| Tax (@ 30%) | (1.5) | (1.2) | ||

| –––– | –––– | |||

| PAT | 3.5 | 2.8 | ||

| –––– | –––– | |||

| Return on equity | = $3.5m/$20m × | = $2.8m/$10m × | ||

| 100 | 100 | |||

| = 17.5% | = 28% | |||

The financial performance of the two funding options is exactly the same for ROCE. This should not be a surprise given that ROCE is an indication of performance before financing, or underlying performance.

- When considering the ROE we see that the geared option achieves a higher return than the equity option. This is because the debt (10%) is costing less than the return on capital (25%). The excess return on that part funded by debt passes to the shareholder enhancing their return. The only differences between ROCE and ROE will be due to taxation and gearing.

4 Agency effects

Agency costs have a further impact on a firm’s practical financing decisions.

Where gearing is high, the interests of management and shareholders may conflict with those of creditors.

Management may for example:

- gamble on high-risk projects to solve problems

- pay large dividends to secure company value for themselves

- hide problems and cut back on discretionary spending

- invest in higher risk business areas than the loan was designated to fund.

In order to safeguard their investments lenders/debentures holders often impose restrictive conditions in the loan agreements that constrains management’s freedom of action: these may include restrictions:

- on the level of dividends

- on the level of additional debt that can be raised

- on acceptable working capital and other ratios

- on management from disposing of any major asset without the debenture holders’ agreement.

These effects may:

- encourage use of retained earnings

- restrict further borrowing

- make new issues less attractive to investors.

More on agency effects

In a situation of high gearing, shareholder and creditor interests are often at odds regarding the acceptability of investment projects.

Shareholders may be tempted to gamble on high-risk projects as if things work out well they take all the ‘winnings’ whereas if things turn out badly the debenture holders will stand part of the losses, the shareholders only being liable up to their equity stake.

There are further ways in which managers (appointed by shareholders)

can act in the interests of the shareholders rather than the debt holders:

Dividends

We have seen how shareholders may be reluctant to put money into an ailing company. On the other hand they are usually happy to take money out. Large cash dividends will secure part of the company’s value for the shareholders at the expense of the creditors.

Playing for time

In general, because of the increasing effect of the indirect costs of bankruptcy, if a firm is going to fail, it is better that this happens sooner rather than later from the creditors’ point of view. However, managers may try to hide the extent of the problem by cutting back on research, maintenance, etc. and thus make ‘this year’s’ results better at the expense of ‘next year’s’.

Changing risks

The company may change the risk of the business without informing the lender. For example, management may negotiate a loan for a relatively safe investment project offering good security and therefore carrying only modest interest charges and then use the funds to finance a far riskier investment. Alternatively management may arrange further loans which increase the risks of the initial creditors by undercutting their asset backing. These actions will once again be to the advantage of the shareholders and to the cost of the creditors.

It is because of the risk that managers might act in this way that most loan agreements contain restrictive covenants for protection of the lender, the costs of these covenants to the firms in terms of constraints upon managers’ freedom of action being a further example of agency costs.

Covenants used by suppliers of debt finance may place restrictions on:

- issuing new debt – with a superior claim on assets

- dividends – growth to be linked to earnings

- merger activity – to ensure post-merger asset backing of loans is maintained at a minimum prescribed level

- investment policy.

Contravention of these agreements will usually result in the loan becoming immediately repayable, thus allowing the debenture holders to restrict the size of any losses.

5 Specific financing options

Recap of basic financing options

The basic choice for a business wanting to raise new finance is between equity finance and debt finance.

Equity finance

This is finance raised by the issue of shares to investors.

Equity holders (shareholders) receive their returns as dividends, which are paid at the discretion of the directors. This makes the returns potentially quite volatile and uncertain, so shareholders generally demand high rates of return to compensate them for this high risk.

From the business’s point of view therefore, equity is the most expensive source of finance, but it is more flexible than debt given that dividends are discretionary (subject to the issues discussed in Chapter 5: The dividend decision).

Debt finance

Short term debt finance

In the short term, businesses can raise finance through overdrafts or short term loans.

Overdrafts are very flexible, can be arranged quickly, and can be repaid quickly and informally if the company can afford to do so. However, if the bank chooses to, it can withdraw an overdraft facility at any time, which could leave a company in financial trouble.

A short term loan is a more formal arrangement, which will be governed by an agreement which specifies exactly what amounts should be paid and when, and what the interest rate will be.

Long term debt finance

Long term debt finance tends to be more expensive than short term finance, unless the debt is secured, when the reduction in risk brings down the cost. Long term debt tends to be used as an alternative to equity for funding long term investments. It is cheaper than equity finance, since the lender faces less risk than a shareholder would, and also because the debt interest is tax deductible. However, the interest is an obligation which cannot be avoided, so debt is a less flexible form of finance than equity.

Specific equity financing options

The main options for companies wishing to raise equity finance are:

- rights issue to existing shareholders – this option is the simplest method, providing the existing shareholders can afford to invest the amount of funds required. The existing shareholders’ control is not diluted.

- public issue of shares – gaining a public listing increases the marketability of the company’s shares, and makes it easier to raise further equity finance from a large number of investors in the future. Becoming a listed company is an expensive and time-consuming process, and once listed, the company has to face a higher level of regulation and public scrutiny. Also, since the company’s shares are likely to become widely distributed between many investors, the threat of takeover increases when a company becomes listed.

- private placing – ‘private equity finance’ is the name given to finance raised from investors organised through the mediation of a venture capital company or private equity business. These investors do not operate through the formal equity market, so raising private equity finance does not expose the company to the same level of scrutiny and regulation that a stock market listing would. Private equity is often perceived as a relatively high risk investment, so investors usually demand higher rates of return than they would from a stock market listed company. Business Angels are a source of private equity finance for small companies.

The article ‘Being an Angel’ in the Technical Articles section of the ACCA website covers Business Angels in more detail.

Stock Exchange listing requirements

If a company decides to raise equity finance from the local capital market, it must comply with the listing requirements of the capital market. For illustration, the listing requirements for the London Stock Exchange are given below:

Track record requirements

The company must be able to provide a revenue earnings record for at least 75% of its business for the previous 3 years. Also, any significant acquisitions in the 3 years before flotation must be disclosed.

Market capitalisation

The shares must be worth at least £700,000 at the time of listing.

Share in public hands

At least 25% of the shares must be in public hands.

Future prospects

The company must show that it has sufficient working capital for its current needs and for the next 12 months. More generally, a description of future plans and prospects must be given.

Audited historical financial information

This must be provided for the last 3 full years, and any published later interim period.

Corporate governance

The Chairman and Chief Executive roles must be split, and half the Board should comprise non-executive directors. There must be an independent audit committee, remuneration committee and nomination committee.

The company must provide evidence of a high standard of financial controls and accounting systems.

Acceptable jurisdiction and accounting standards

The company must be properly incorporated and must use IFRS and equivalent accounting standards.

Other considerations

A sponsor/underwriter will need to make sure that the company has established procedures which allow it to comply with the listing and disclosure rules.

Regulations in other countries

Companies must meet an exchange’s requirements to have their stocks and shares listed and traded there, but requirements vary by stock exchange. The above points all refer to the London stock exchange. Some examples of other major global stock exchange requirements are:

Bombay/Mumbai Stock Exchange: Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) has requirements for a minimum market capitalisation of INR250 million (approx. US$3.9 million) and minimum public float equivalent to INR100 million (approx. US$1.5 million).

New York Stock Exchange: To be listed on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) a company must have publicly held shares worth at least $100 million and must have earned more than $10 million in total over the last three years.

NASDAQ Stock Exchange: To be listed on the NASDAQ a company must comply with one of four listing requirements covering earnings levels, market capitalisation, cash flows, revenues and asset values.

Delisting

Delisting is the removal of a listed security from the exchange on which it trades.

Stock is removed from an exchange because the company for which the stock is issued, whether voluntarily or involuntarily, is not in compliance with the listing requirements of the exchange. The reasons for delisting include violating regulations and/or failing to meet financial specifications set out by the stock exchange.

Companies that are delisted are not necessarily bankrupt, and may continue trading over the counter.

In order for a stock to be traded on an exchange, the company that issues the stock must meet the listing requirements set out by the exchange.

Listing requirements include minimum share prices, certain financial ratios, minimum sales levels, and so on. If listing requirements are not met by a company, the exchange that lists the company’s stock will probably issue a warning of non-compliance to the company.

If the company’s failure to meet listing requirements continues, the exchange may delist the company’s stock.

Alternatively, a company may choose to delist its own stock, or indeed the stock of a company that it has taken over.

A listing on the stock exchange brings with it extra scrutiny of the company’s affairs, and attracts a wide range of investors, some of whom may have very different objectives (say short term gain) from the original shareholders.

Faced with this scrutiny and conflict, the company may choose to delist its own shares from the exchange and return to private ownership.

Dark pool trading systems

Definition

Dark pool trading relates to the trading volume in listed stocks created by institutional orders that are unavailable to the public. The bulk of dark pool trading is represented by block trades facilitated away from the central exchanges.

It is also referred to as the ‘upstairs market’, or ‘dark liquidity’, or just ‘dark pool’.

The dark pool gets its name because details of these trades are concealed from the public, clouding the transactions like murky water. Some traders that use a strategy based on liquidity feel that dark pool trading should be publicised, in order to make trading more ‘fair’ for all parties involved. Indeed, some stock exchanges have prohibited dark pool trading.

The problem with dark pool trading

If an institutional investor looking to make a large block order (thousands or millions of shares) makes a trade on the open market, investors across the globe will see a spike in volume.

This might prompt a change in the price of the security, which in turn could increase the cost of purchasing the block of shares. When thousands of shares are involved, even a small change in share price can translate into a lot of money. If only the buyer and seller are aware of the transaction, both can skip over market forces and get a price that’s better suited to them both.

The rise in popularity of dark pool trading raises questions for both investors and regulators. With a significant proportion of trades occurring without the knowledge of the everyday investor, information asymmetry becomes an issue of greater importance.

More on private equity and venture capital

Private equity is an asset class consisting of equity securities and debt in operating companies that are not publicly traded on a stock exchange.

A private equity investment will generally be made by a private equity firm, a venture capital firm or an angel investor. Each of these categories of investor has its own set of goals, preferences and investment strategies; however, all provide working capital to a target company to nurture expansion, new-product development, or restructuring of the company’s operations, management, or ownership.

Among the most common investment strategies in private equity are: leveraged buyouts, venture capital, growth capital, distressed investments and mezzanine capital.

In a typical leveraged buyout transaction, a private equity firm buys majority control of an existing or mature firm, to try to improve its results before selling it or listing it on the stock market.

This is distinct from a venture capital or growth capital investment, in which the investors (typically venture capital firms or angel investors) invest in young, growing or emerging companies, and rarely obtain majority control.

Specific debt financing options

A company seeking to raise long term debt finance will be constrained by its size, its debt capacity and its credit rating.

Small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) may make use of private lending through family, friends and other small business investors. The usual starting point is to approach a bank, which will make a lending decision based on the company’s business plan.

Alternatively, companies often elect to lease assets rather than purchasing them. Leasing is often viewed as a type of debt financing, because it requires a company to commit to a fixed stream of payments for a number of years, in a similar way to repaying loan capital and interest. The main consideration with lease financing is that (depending on the terms of the specific lease) the ownership of the asset often stays with the lessor. While this can be attractive in that maintenance costs are reduced, it does mean that the company doesn’t actually own the asset so cannot claim the tax depreciation allowances or benefit from an increase in asset value.

Larger companies have the following additional options:

- Bond issue – this is an attractive way of raising large amounts of debt finance, at a low rate of interest. There are however significant issue costs and there is a risk that the issue might not be fully subscribed (unless it is underwritten). Bonds may be issued in the domestic, or an overseas, capital market.

- Debenture issue – debentures are asset backed securities (i.e. lower risk for investors).

- Convertible bond issue – convertibles carry the right of conversion to equity at some future date. This makes the bond more attractive to a potential investor.

- Mezzanine finance – the most risky type of debt from the lender’s point of view. The holder of mezzanine debt is ranked after all the other debt holders on a liquidation, and the debt is unsecured. A high coupon rate has to be paid to compensate the investor for this risk.

- Syndicated loan – for large amounts of debt finance, where one bank is not prepared to take the risk of lending such a large amount, a loan may be raised from a syndicate of banks. Rates of interest tend to be slightly higher than those in the bond market, but transaction costs are low and loans can be arranged much quicker than a bond issue.

6 Islamic finance

Islamic finance has the same purpose as other forms of business finance except that it operates in accordance with the principles of Islamic law (Sharia). The basic principles covered by Islamic finance include:

- Sharing of profits and losses.

- No interest (riba) allowed.

- Finance is restricted to Islamically accepted transactions. i.e. no investment in alcohol, gambling etc.

Therefore, ethical and moral investing is encouraged. Instead of interest being charged, returns are earned by channelling funds into an underlying investment activity, which will earn profit. The investor is rewarded by a share in that profit, after a management fee is deducted by the bank. The main Islamic finance products are:

- Murabaha (trade credit)

- Ijara (lease finance)

- Sukuk (debt finance)

- Mudaraba (equity finance)

- Musharaka (venture capital)

- Salam and Istisna (forward contracts).

Student Accountant articles

Two articles in the Technical Articles section of the ACCA website cover the topic of Islamic finance.

More details on Islamic finance

The Islamic economic model has developed over time based on the rulings of Sharia on commercial and financial transactions. The Islamic finance framework seen today is based on the principles developed within this model. These include:

- An emphasis on fairness such that all parties involved in a transaction can make informed decisions without being misled or cheated. Equally reward should be based on effort rather than for simple ownership of capital.

- The encouragement and promotion of the rights of individuals to pursue personal economic wellbeing, but with a clear distinction between what commercial activities are allowed and what are forbidden (for example, transactions involving alcohol, pork related products, armaments, gambling and other socially detrimental activities). Speculation is also prohibited (so instruments such as options and futures are not allowed). Ethical and moral investing is encouraged.

- The strict prohibition of interest (riba). Instead interest is replaced with cash flows from productive sources, such as returns from wealth generating investment activities.

How returns are earned

Riba is defined as the excess paid by the borrower over the original capital borrowed i.e. the equivalent to interest on a loan. Its literal translation is ‘excess’. Within the conventional banking system, a bank get access to funds by offering interest to depositors. It will then apply those funds by lending money, on which it charges interest. The bank makes a profit by charging more interest on the money it lends than it pays to its depositors.

This process is outlawed under Islamic finance. In an Islamic bank, the money provided by depositors is not lent, but is instead channelled into an underlying investment activity, which will earn profit. The depositor is rewarded by a share in that profit, after a management fee is deducted by the bank. For example, in an Islamic mortgage transaction, instead of loaning the buyer money to purchase the item, a bank might buy the item itself from the seller, and resell it to the buyer at a profit, while allowing the buyer to pay the bank in instalments. However, the bank’s profit cannot be made explicit and therefore there are no additional penalties for late payment. In effect, the interest is replaced with cash flows from productive sources, such as returns from wealth generating investment activities and operations. These include profits from trading in real assets and cash flows from the transfer of the right to use an asset (for example, rent).

Sharia boards (SBs)

Sharia Boards (SBs) ensure that all products and services offered by Islamic banks and other Islamic financing institutions (IFIs) are compliant with the principles of Sharia rules.

They review and oversee all new product offerings made by the IFIs and make judgments on an individual case-by-case basis, regarding their acceptability with Sharia rulings. Additionally, SBs often oversee Sharia compliant training programmes for an IFI’s employees and participate in the preparation and approval of the IFIs’ annual reports.

SBs are normally made up of a mixture of Islamic scholars and finance experts to ensure that fair and reasonable judgments are made. Where necessary, the finance experts can explain the products to the Islamic scholars. The Islamic scholars often sit on several SBs of a number of different IFIs. SBs are, in turn, supervised by the International Association of Islamic Bankers (IAIB).

SBs face several challenges when making judgments. Sharia law can be open to different interpretations, leading to different outcomes on the acceptability of the same products by different SBs and Islamic scholars.

Furthermore, precedents set by SBs are not binding, and changes in SBs’ personnel over time may shift the balance of the SB’s collective opinions and judgments on the acceptability of existing and new products.

SBs need considerable resources to operate effectively, and IFIs need to ensure that their SB members are well informed about the developments and trends in global financial markets.

Specific Islamic financing methods

Islamic sources of finance

In Islamic Banking there are broadly 2 categories of financing techniques:

- ‘Fixed Income’ modes of finance – murabaha, ijara, sukuk, salam, istisna

- Equity modes of finance – mudaraba, musharaka.

Each of these is discussed in more detail below.

Murabaha

Murabaha is a form of trade credit or loan. The key distinction between a murabaha and a loan is that with a murabaha, the bank will take actual constructive or physical ownership of the asset. The asset is then sold onto the ‘borrower’ or ‘buyer’ for a profit but they are allowed to pay the bank over a set number of instalments. The period of the repayments could be extended but no penalties or additional mark-up may be added by the bank. Early payment discounts are not welcomed (and will not form part of the contract) although the financier may choose (not contract) to give discounts.

Ijara

Ijara is the equivalent of lease finance; it is defined as when the use of the underlying asset or service is transferred for consideration. Under this concept, the Bank makes available to the customer the use of assets or equipment such as plant, office automation, or motor vehicles for a fixed period and price. Some of the specifications of an Ijara contact include:

- The use of the leased asset must be specified in the contract.

- The lessor (the bank) is responsible for the major maintenance of the underlying assets (ownership costs).

The lessee is held for maintaining the asset in good shape

Sukuk

Within other forms of business finance, a company can issue tradable financial instruments to borrow money. Key features of these debt instruments are that they

- don’t give voting rights in the company.

- give right to profits before distribution of profits to shareholders.

- may include securities and guarantees over assets.

- include interest based elements.

All of the above are prohibited under Islamic law. Instead, Islamic bonds (or sukuk) are linked to an underlying asset, such that a sukuk-holder is a partial owner in the underlying assets and profit is linked to the performance of the underlying asset. So for example a sukuk-holder will participate in the ownership of the company issuing the sukuk and has a right to profits (but will equally bear their share of any losses).

Sukuk is about the finance provider having ownership of real assets and earning a return sourced from those assets. This contrasts with conventional bonds where the investor has a debt instrument earning the return predominately via the payment of interest (riba). Riba or excess is not allowed under Sharia law.

There has been considerable debate as to whether sukuk instruments are akin to conventional debt or equity finance. This is because there are two types of sukuk:

Asset based – raising finance where the principal is covered by the capital value of the asset but the returns and repayments to sukuk holders are not directly financed by these assets.

Asset backed – raising finance where the principal is covered by the capital value of the asset but the returns and repayments to sukuk holders are directly financed by these assets.

Salam

Salam contracts are similar to forward contracts, where a commodity

(or service) is sold today for future delivery. Cash is received immediately from the bank and the quantity, quality, and the future date and time of delivery are determined immediately. The sale will probably be at a discount so that the bank can make a profit.

In turn, the bank would probably sell the contract to another buyer for immediate cash and profit, in a parallel Salam arrangement. Salam contracts are prohibited for commodities such as gold, silver and other money-type assets.

Istisna

Istisna contracts are often used for long-term, large construction projects of property and machinery. Here, the bank funds the construction project for a client that is delivered on completion to the bank’s client. The client pays an initial deposit, followed by instalments, to the bank, the amount and frequency of which are determined at the start of the contract.

Mudaraba

Mudaraba is a special kind of partnership where one partner gives money to another for investing it in a commercial enterprise. The investment comes from the first partner (who is called ‘rab ul mal’), while the management and work is an exclusive responsibility of the other (who is called ‘mudarib’). The Mudaraba (profit sharing) is a contract, with one party providing 100% of the capital and the other party providing its specialist knowledge to invest the capital and manage the investment project. Profits generated are shared between the parties according to a pre-agreed ratio. In a Mudaraba only the lender of the money has to take losses. This arrangement is therefore most closely aligned with equity finance.

Musharaka

Musharaka is a relationship between two or more parties, who contribute capital to a business, and divide the net profit and loss pro rata. It is most closely aligned with the concept of venture capital. All providers of capital are entitled to participate in management, but are not required to do so.

The profit is distributed among the partners in pre -agreed ratios, while the loss is borne by each partner strictly in proportion to their respective capital contributions.

Advantages and limitations of using Islamic finance Advantages of using Islamic finance

Corporations, individuals and IFIs engaged in raising and issuing funding based on Islamic finance virtues may be viewed as belonging in stakeholder-type partnerships that are engaged in deriving benefits from ethical, fair business activity. The result of these partnerships is one of mutual interest, trust and co-operation. The ethical stance and fair dealing of Islamic finance virtues means that partnerships, business activity and profit creation comes from benefiting the community as a whole.

Since the virtues of Islamic finance and enterprise prohibit speculation and short-term opportunism, it encourages all parties to take a longer term view of success from the partnership. It focuses all the parties’ attention on creating a successful outcome to the venture. This should result in a more stable financial environment. Indeed, literature in this area suggests that had banks and other financial institutions conducted their business activity based on Islamic finance principles, the negative impact of the banking and sovereign debt financial crises would have been much reduced.

IFIs or conventional financial institutions with products based on Islamic finance principles gain access to Muslim funds across the world and provide finance for organisations and individuals who need them. It is estimated that Islamic financial assets have exceeded $1,600bn worldwide. As the world emerges from the global financial crisis and business activity increases, this should increase. Furthermore, access to Islamic finance is not restricted to Muslim communities only. The wider business community could have access to new sources of finance. This may be particularly attractive to corporations focused on ethical investments that Islamic finance virtues stipulate.

Limitations of using Islamic financing methods

Because of the prohibitions of riba and on speculation, IFIs may be slower to react to market demand and changes. They may lack sufficient flexibility in their product offering when compared to conventional financial institutions and may be less able to take advantage of short-term opportunities.

Moral hazard and principal-agent issues may be more pronounced between IFIs and organisations and individuals to whom they lend funds. This is because Islamic finance virtues stipulate close relationships from partnership -like arrangements. However, information asymmetry between the IFI and the borrower of funds will always exist. Therefore, costs related to increased level of due diligence and negotiating are probably higher for IFIs.

Costs related to developing new financial products may also be higher for IFIs because not only will the products have to comply with normal financial laws and regulations but also with Sharia rules. As stated above, the resources required by SBs can be considerable.

Added to this, because these financial products need to go through stages of compliance and layers of complications before they are approved, the approval process can take time. The pace of innovation of new Islamic financial products may be considerably slower than that of conventional products. This may make the IFI less able to compete with conventional financial institutions and may make it restrict its activities to smaller, niche markets. Some Islamic financial products may not be compatible with international financial regulation – for example, a diminishing Musharaka contract may not be an acceptable mortgage instrument in law, although it could be constructed as such. The need to ensure that such products comply with regulations may increase legal and insurance costs.

The interpretation of Sharia rulings may allow certain Islamic finance products to be acceptable in some markets, but not in others. This has led to some Islamic scholars, who are experts in Sharia and finance, to criticise a number of product offerings. For example, some Murabaha contracts have been criticised because their repayments have been based on prevailing interest rates rather than on economic or profit conditions within which the asset will be used. Some Sukuk bonds have faced similar criticisms in that their repayments have been based on prevailing interest rates, they have been credit-rated and their redemption value is based on a nominal value rather than on a market value, and thereby, perhaps, making them too close to conventional bonds and their repayments too similar to riba. On the other hand, the opposite argument could be that in order to make Islamic financial products competitive in all markets, their valuations need to be comparable. Therefore, benchmarking them using conventional means is necessary.

So far the discussion on limitations has focused on IFIs, as providers of Islamic finance. It is also important to consider the drawbacks and challenges that corporations may face when using Islamic finance.

From the above discussion, the costs related to developing and gaining approval for Islamic financial products is likely to be passed down to customers and possibly make these products more expensive. In addition to this, access to new products and flexibility within existing products may be limited, due to the more complicated approval process that is necessary. These more expensive and less flexible sources of finance may make the corporation using them less competitive when compared to rivals who have access to cheaper, more flexible sources of finance.

The partnership nature of Islamic finance contracts may also cause agency type issues within corporations. These may be more prevalent in joint venture type situations or where the diverse range of stakeholders may make it more difficult for corporations to determine and act upon the importance of various stakeholder groups. For example, in the case of a Musharaka contract, where the IFI and the organisation are both involved in the management of a project, dealing with other stakeholder groups may be more challenging.

Before the financial crisis, trading in asset backed and securitised Sukuk products, issued by corporations, has been limited (a notable exception was Sukuk products denominated in Malaysian ringgits). Furthermore, since the financial crisis, issuance in new Sukuk products has reduced somewhat.

Using Islamic finance may also increase the cost of capital for a corporation. For example, it may be more difficult to demonstrate that repayments for Mudaraba, Musharaka and Sukuk contracts are like debt, and therefore they may not attract a tax-shield. However, an equivalent organisation which raises the same finance using conventional debt finance may be able to lower its cost of capital due to tax-shields and therefore increase the value of its investment.

7 Financing foreign projects – Introduction

Foreign currency denominated finance

Large companies can borrow money in foreign currencies as well as their own domestic currency from banks or capital markets at home or abroad. Often large companies set up foreign subsidiaries to invest in foreign projects and arrange the financing.

The main reason for wanting to borrow in a foreign currency is to fund a foreign investment project or foreign subsidiary. The foreign currency borrowing provides a hedge of the value of the project or subsidiary to protect against changes in value due to currency movements. The foreign currency borrowing can be serviced from cash flows arising from the foreign currency investment.

In the developed countries of the world, companies can choose which currency they prefer for both bank borrowings and bonds.

In most developing countries, companies will need to raise finance in an international currency such as US dollars.

Financing options for international investments

The main options are:

- use the investment’s own free cash flows

- use finance raised in the parent entity’s home country (denominated in either the parent’s currency or the currency of the subsidiary)

- use finance raised in the subsidiary’s country

- use finance raised in a completely separate country.

More detail on the financing of international investment projects Using free cash flows

A foreign subsidiary or project could rely upon its own internally generated funds.

This would avoid many of the problems of international financing, but is unlikely to result in the necessary level of expansion to meet high growth objectives, and is not suitable for new foreign ventures whose cash flows may be low at first.

Finance raised by the parent

Funds could be raised by the parent company and transferred to subsidiary entities by way of a combination of equity and loans. The main advantage of this method is that the parent company is more likely to have a better reputation and creditworthiness than the subsidiary and therefore have better access to funds at finer rates. A centralised treasury function at the parent may also have the expertise to and financial backing to be able to choose to access funds from a wider range of sources, including more complex products. Indeed, it may be possible to extend funds to a foreign subsidiary as part of a larger bond issue or bank debt arrangement.

However, if exchange controls exist this method can become difficult and expensive.

If the borrowing is denominated in the parent’s domestic currency, this will in no way reduce foreign exchange risk through matching. However, if the funds are denominated in the subsidiary’s currency, the foreign currency borrowing can be designated as a hedge of the net investment in the foreign subsidiary for hedge accounting purposes to reduce the impact of fluctuations in value due to currency movements. Interest payable on the foreign currency borrowing can also be set against income from the subsidiary, again reducing currency exposure to some extent.

General disadvantages of this method (whether the funds are denominated in the domestic or the foreign currency) are:

- The entity will also be more exposed to political risk. If the investment is lost, perhaps through a war or expropriation by a foreign government, the liability will still remain intact.

- Also, if the investment is a subsidiary entity, failure of the subsidiary would leave the parent entity with the liability in the same way.

Finance raised by the subsidiary

Finance raised by the subsidiary is likely to be denominated in the subsidiary’s currency.

This method will result in a reduction in risk. Foreign exchange risk will again be reduced, since the exposure of the parent company to the net worth of the subsidiary will be reduced by the amount of the foreign currency borrowing. However, complete elimination of the risk through matching will not be possible due to the likelihood of thin capitalisation rules in the foreign country which may restrict the proportion of debt capital allowed. The currency exposure of the parent to annual reported foreign currency profits from the subsidiary would also be reduced by the extent of the interest charges paid by the foreign subsidiary on the borrowings.

Political risk can also be reduced since, if the investment is lost, the liability will be eliminated as well.

Difficulties may be experienced with this method of finance if the subsidiary company does not have sufficient history or reputation to be able to raise bank debt or the country concerned does not have a well-developed capital market.

On the other hand, financing in the subsidiary’s country can make such investments more acceptable to that country since it is then seen that not all of the profits made are sent to the parent entity’s country.

Most governments take steps to encourage international investors since they are beneficial to that country’s economy, creating employment and wealth. Such encouragement often takes the form of grants, subsidies and cheap or guaranteed finance. These incentives should be taken into account when considering international investments and their financing.

Finance raised in a third currency

Finance can today be raised in a variety of different currencies, from a variety of capital markets in many different countries.

The main reason for raising money in other currencies is that interest rates may be substantially lower than in the entity’s home country or in the country where an investment is intended.

However, if the interest cost is lower, then it is likely that the currency borrowed is strong, and will therefore appreciate with respect to other currencies (as per the interest rate parity theory introduced earlier). The expected exchange loss on the borrowings would therefore offset any benefit through a lower interest rate.

Specific foreign currency financing options

There is a variety of sources of foreign currency denominated finance available:

Short-term funding:

- Eurocurrency loans.

- Syndicated loans.

- Short-term syndicated credit facilities.

- Multiple option facilities.

Long-term funding:

- Syndicated loans.

Short term funding options

Eurocurrency loans

Multinational companies and large companies, which are heavily engaged in international transactions, may require funds in a foreign currency.

A Eurocurrency loan is a loan by a bank to a company denominated in currency of a country other than that in which they are based.

e.g. A UK company acquiring a dollar loan from a UK bank operating in the Eurocurrency market has acquired a Eurodollar loan.

Loans can take a variety of forms:

- Straight loans.

- Lines of credit.

- Revolving loans.

Borrowers looking to eurocurrency loans must have first class credit ratings and wish to deal in large sums of money.

A variety of factors will influence the decision over whether to borrow in the domestic currency or in a foreign currency. The most important are:

- the currency required

- cost and convenience

- the size of loans.

The currency required

Companies may have needs for foreign currency funds for either trading or financing purposes and the Eurocurrency market may be a more convenient or cheaper source of such funds than in the domestic market of the country whose currency is needed.

Cost and convenience

Eurocurrency loans may be:

- cheaper if interest rates are lower; even if interest rate differentials are small this may be significant for large loans

- quicker to arrange

- unsecured and large companies can rely on their credit ratings rather than the security that can offer.

The size of loans

The Eurocurrency markets hold very large funds and for companies wishing to obtain very large loans this may be a viable alternative to domestic banking sources.

As well as a conventional Eurocurrency loans, the international money markets have developed alternative short-term credit instruments.

Syndicated loans

For large loans a single bank may not be willing (due to risk exposure) or able to lend the whole amount.

A syndicated loan is a loan made to a borrower by two or more participants but is governed by a single loan agreement. The loan is structured by an arranger and each syndicate participant contributes a defined percentage of the loan and receives the same percentage of the repayments.

The syndicated loan market is made up of international lenders and was originally limited to global firms for acquisitions and other major investments. This is for the following reasons:

- Cost – being international, loans can often be raised avoiding national regulation and are thus cheaper.

- Speed – the market is very efficient so large loans can often be put together quickly if necessary.

- By diversifying lending sources borrowers may be able to eliminate foreign exchange rate risk.

However, the market has expanded rapidly with smaller and medium sized firms borrowing funds – syndicated loans as small as $10 million are now commonplace.

Syndicated credits

Similar to syndicated loans, syndicated credits allow a borrower to borrow funds when it requires, but can choose not take up the full amount of the agreed facility. These are expensive funds used commonly

- to fund takeovers

- to refinance debts incurred during a takeover.

Multiple option facilities

Recently developed financial instruments, these are designed to give the borrower a choice of available funds.

Commonly this will combine

- a panel of banks to provide a credit standby at a rate of interest linked to LIBOR

- another panel of banks to bid to provide loans when the borrower needs cash.

These funds can be in a variety of forms and denominated in a variety of currencies.

Euronotes

Euronotes have the following features:

- Firms issue promissory notes which promise to pay the holder a fixed sum of money on a specific date or range of dates in the future.

- The Eurobond market acts as both a primary and secondary market often underwritten by banks through revolving underwriting facilities.

- Can be are short or medium term issued in single or multiple currencies. The medium-term notes bridge the gap between the short-term issues and the longer-term Eurobonds.

Eurobonds

The most important source of longer term funding is the Eurobond.

Eurobonds are:

- long term (3–20 years)

- issued and sold internationally

- denominated in a single currency

- fixed or floating interest rate bonds.

They are suitable for organisations that require:

- large capital sums for long periods

- borrowing not subject to domestic regulations.

However, a currency risk may arise if the investment the bonds are funding generates net revenues in a currency different from that the bond is denominated in.

More details on Eurobonds

In addition to short-term credit, companies and government bodies may wish to raise long-term capital. For this there is an international capital market corresponding to the international money market but dealing in longer-term funding with a different range of financial instruments. The most important of these is the Eurobond.

Eurobonds are long-term loans, usually between 3 and 20 years duration, issued and sold internationally and denominated in a single currency, often not that of the country of origin of the borrower. They may be fixed or floating interest rate bonds. The latter were introduced since inflation, especially if unpredictable, made fixed rate bonds less attractive to potential borrowers.

Eurobonds are suitable sources of finance for organisations that require:

- large capital sums for long periods, e.g. to finance major capital investment programmes

- borrowing not subject to domestic regulations especially exchange controls which may limit their ability to export capital sums.

However, Eurobonds involves the borrower in currency risk. If the capital investment generates revenue in a currency other than that in which the bond is denominated and exchange rates change the borrower will:

- suffer losses if the currency in which the bond is denominated strengthens against the currency in which the revenues are denominated

- make gains if the currency in which the bond is denominated weakens against the currency in which the revenues are denominated.

Test your understanding 1

Issues to raise would include:

- Retained earnings – often a preferred source of funds for smaller firms, these cannot be easily used here as the family shareholders expect significant dividends. This means that outside finance must be considered.

- High level of required funding relative to the size of the firm – could be perceived by potential investors as increasing business risk even though the expansion is in the same industry. This would increase required returns of equity investors before the increase in debt funding is even considered.

- Assets for loan security – since land and buildings are already mortgaged, the machinery will have to be used as security. The attractiveness of this depends on whether they are specialised or would have a ready resale market.

- Gearing levels – the company is already geared but it is not clear whether the current level is optimum. Raising further debt finance, subject to the taxation considerations below, should reduce the overall cost of capital, but such a significant sum is likely to be seen as high risk. The fixed interest payments could bankrupt the firm if the expected growth does not occur. This is likely to increase the required returns of shareholders and may mean that debt lenders demand higher returns than are being paid on the current loans.

- Taxation – the high levels of investment will attract tax allowable depreciation. Depending on the current tax position of the firm and the treatment of this TAD, the company may find itself in a non-tax-paying position. This would negate the benefits of the cheaper debt finance.

- Agency costs – lenders often impose restrictive covenants on the company. This is particularly likely where such a significant level of funds is to be raised. A company largely in family control may be reluctant to have such restrictions, especially on dividend payments for example, which are appear to be used here to provide the family members with a source of income.

- Risk profile – the family members may be reluctant to take on further debt. The risk of bankruptcy mentioned above, is of greater concern to undiversified family owners than to the typically well diversified outside investor.

- Control – since the family retain voting control, the choice may be between debt finance and a rights issue, unless they are willing to give up control. If they do not have the funds to inject, a loan may be the only choice.

- Consideration should be given to alternatives such as leasing the machinery, or seeking venture capital funding (although that too may also require a loss of absolute family control).