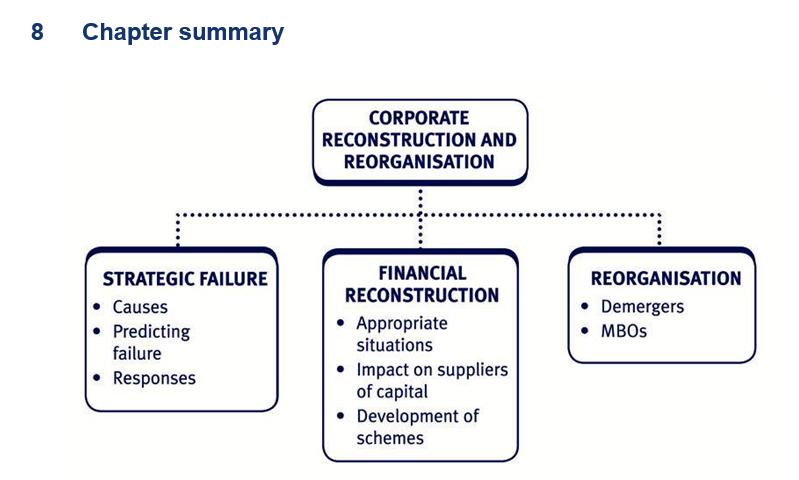

Financial distress and corporate failure

What is corporate failure?

Corporate failure occurs when a company cannot achieve a satisfactory return on capital over the longer term. If unchecked, the situation is likely to lead to an inability of the company to pay its obligations as they become due.

If a company is in financial distress, corporate failure will follow unless the company’s problems can be identified and corrected.

Therefore, it is important that we can recognise the main causes of financial distress.

2 The five core causes of financial distress

The five core causes of financial distress in a business are:

- Revenue failure, caused by either internal or external factors. Revenue failure may be through a loss of orders (market failure) or through the acceptance of business which does not contribute to the growth of shareholder value.

- Cost failure, caused by weak cost control, changes in technology, inappropriate accounting policies, inadvertent or exceptional cost burdens, poor financial management or failure of effective governance.

- Failure in asset management, through failure to invest in appropriate technology, poor working capital management, inappropriate write off and reinvestment or poor organisation of the available assets.

- Failure in liability management, through failure to manage the company’s relationship with the money markets, weak control of interest rate risk and currency risk or unsustainable credit policies.

- Failure of capital management, through either over or under-capitalisation or poor management of the company’s relationship with the capital markets and in particular the company’s debt portfolio and the optimisation of its cost of capital.

In practice problems rarely occur in isolation. A business is an internal and external network of relationships of assets and individuals, so problems in one area invariably have consequences elsewhere.

Research into the causes of corporate failure

A major study (Grinyer, Mayes et al., 1988) examined reasons why firms experience decline. Chief among the reasons found (in order of frequency) in the study were:

- adverse changes in total market demand

- intensification of competition

- high cost structure

- poor financial controls

- weak management

- failure of a large project

- poor marketing effort

- poor acquisitions

- poor quality.

Clearly, some of these are not, in themselves, strategic issues. Much can be done, by strong management accounting, to reduce costs, improve financial information and controls, improve project management and quality control systems, without changing strategy. It is always worth repeating the adage that strategic management builds on good operations management. No strategy can compensate for operational inefficiency in the long run.

However, many of the items listed involve changes in the market place, and the way that competition is carried out. Strategy is chiefly about adapting the firm to such changes, and strategic failure results when the organisation does not change as quickly as the market.

An illustration of financial distress

Norman English was a mechanical engineer, who founded his own company in the early 1970s, producing automotive parts. His early successes enabled him to diversify into a wide range of component manufacturing, and eventually into assembly of unbranded products. Many households are entirely unaware that the product they identify by an expensive, foreign brand was actually made locally.

In the mid-1980s, the company was floated and attracted favourable City opinion. New investment was used to launch into several new projects, and exporting. The latter was particularly well received and, with his forthright views, made Norman English a minor spokesperson for industry. Public speaking and committee work took a great part of his time. During the 1990s, company size increased by more than five times.

By 2008, Norman was ageing, unwell, and thinking about retirement. For several years, his involvement as CEO had been somewhat peripheral, and he was aware that his middle managers spent some time fighting each other. In the past, he had seen off such problems with his forceful personality and understanding of the business. The geographical spread of the company, and the proliferation of information made it extremely hard for him to keep the issues clear in his mind.

Further, the company’s financial performance was not good and dividends were low. Manufacturing plant was old, and needed replacement. Product design was also looking dated; the firm had been slow to incorporate microchip technology into its products and was increasingly forced into producing budget models with little margin.

A widely-circulated report suggested that the export initiative had never been profitable, but had consumed a great deal of capital. Nonetheless, investors and lenders wanted to feel that Norman English was still in control.

Is this corporate failure? Give reasons for your answer. How has this arisen?

Solution

Although the company has not yet failed, it would seem to be only a question of time. When we look back at the purpose of a strategy, we see that the company is under-performing in most respects. The firm has failed to adapt to the environment – it is no longer producing goods that top firms wish to be associated with. It has failed to develop its resource base, both in terms of plant and learning about the capabilities of recent technologies. It no longer has a sense of purpose about the future, rather it seems that middle and senior managers cannot even agree on how to manage the business in its present state. Finally, it has confused a strategy – exporting – with the purpose of the strategy, to produce a return on investment.

The problem may have arisen in several ways, but it is likely that a formerly dramatic leader has lost his touch, leaving an absence of strategic thinking and energy. There is the added problem that the obvious solution, succession planning, leading to replacement of the CEO, would not be well received by the City. Consequently, this situation has been allowed to continue for longer than usual.

Identifying financial distress

It is possible to identify a business in financial distress by analysing its financial statements.

- Trends in ratios (such as return on capital employed and receivables collection period) can be used to identify the first signs of distress.

- Free cash flow analysis can also give an indication of likely problems.

Ratio analysis

A comprehensive analysis of performance will cover the following four areas:

profitability, liquidity, gearing and stock market ratios.

Key ratios are listed under each of these headings below:

Profitability

Return on capital employed (ROCE), which can be measured as either net operating profit before tax or net operating profit after tax (NOPAT) as a percentage of capital employed.

Asset turnover is the ratio of revenue to capital employed.

Operating profit margin is operating profit expressed as a percentage of revenue.

Liquidity

The most basic measure of liquidity is the current ratio (current assets/current liabilities). However, this ratio is so simplistic that it is difficult to use it for any meaningful analysis. Instead, it is better to focus on the individual elements of working capital separately.

Debtor days (receivables collection period) = (Receivables/Credit sales revenue) × 365

Creditor days (payables payment period) = (Payables/Purchases) × 365 Inventory holding period = (Inventory/Cost of sales) × 365

The firm’s cash operating cycle is calculated as Debtor days + Inventory holding period – Creditor days

Generally, a reduction in the overall length of the cycle indicates an improvement in the entity’s liquidity position.

Gearing

If gearing is too high, the entity might be unable to service its debts. There are two ways of looking at gearing:

Balance sheet (statement of financial position) gearing

Debt value/Equity value, or

Debt value/(Value of equity + debt)

Note that equity value in the accounts is the share capital AND the reserves.

Statement of profit or loss gearing

The key measure is interest cover = Profit before interest and tax/Interest (Finance charges).

It is usually easier to identify potential problems from the statement of profit or loss figure, since a low figure close to unity gives an immediate and obvious cause for concern. Statement of financial position gearing ratios need to be compared (to industry averages and/or prior years) before they can be properly interpreted.

Stock market ratios

Note that if the entity being analysed is not listed, no calculations will be possible in this area.

However, if the entity is listed, this is arguably the most important area, since the ratios in this area will show whether the rest of the market perceives the entity positively or not.

Price-earnings (P/E) ratio = Share price/Earnings per share

Dividend cover = Earnings per share/Dividend per share

Dividend yield = Dividend per share/Share price

Test your understanding 1 – Performance analysis

The following shows the balance sheet (statement of financial position) and statement of profit or loss for Zed Manufacturing for the years ended 31 December 20X7 and 31 December 20X8:

| Summarised statement of profit or loss ($m) | ||

| 20X7 | 20X8 | |

| Sales revenue | 840 | 830 |

| Cost of sales | 554 | 591 |

| –––– | –––– | |

| Gross profit | 286 | 239 |

| Selling, distribution and administration expenses | 186 | 182 |

| –––– | –––– | |

| Profit before interest | 100 | 57 |

| Interest | 6 | 8 |

| –––– | –––– | |

| Profit before tax | 94 | 49 |

| Tax (standard rate 50%) | 45 | 23 |

| –––– | –––– | |

| Profit for the year | 49 | 26 |

| –––– | –––– |

Summarised statement of financial position (balance sheet) ($m)

| Non-current assets: | 20X7 | 20X8 |

| Intangible assets | 36 | 32 |

| Tangible assets at net book value | 176 | 222 |

| –––– | –––– | |

| Current assets: | 212 | 254 |

| Inventory | 237 | 265 |

| Receivables | 105 | 132 |

| Bank | 52 | 13 |

| –––– | –––– | |

| 394 | 410 | |

| –––– | –––– | |

| Total assets | 606 | 664 |

| Equity | –––– | –––– |

| Share capital(ordinary 50c shares) | 100 | 100 |

| Retained earnings | 299 | 348 |

| –––– | –––– | |

| Non-current liabilities: | 399 | 448 |

| Long-term loans | 74 | 94 |

| –––– | –––– | |

| Current liabilities: | 473 | 542 |

| Payables | 133 | 122 |

| –––– | –––– | |

| Total equity and liabilities | 606 | 664 |

| –––– | –––– |

The current share price is $0.80 (it was $1.60 at the end of 20X7).

Required:

Summarise the performance of Zed Manufacturing in 20X8 compared with 20X7.

4 Assessing the risk of corporate failure – Other considerations

Limitations of corporate failure prediction models

There are a number of limitations of ratio analysis as a predictor of corporate failure:

- Ratios are a snapshot – they give an indication of the situation at a given point in time but do not determine whether the situation is improving or deteriorating.

- Further analysis is needed to fully understand the situation, for example a comparison with industry average ratio figures.

- Ratios are only good indicators of performance in the short term.

Practical indicators of financial distress

You should not think that ratio analysis of published accounts and free cash flow analysis are the only ways of spotting that a company might be running into financial distress. There are other possible indicators too. Some of this information might be given to you in an exam case study.

- Information in the published accounts, for example:

– a worsening cash and cash equivalents position shown by the cash flow statement

– very large contingent liabilities

– important post-balance sheet events.

- Information in the chairman’s report and the directors’ report (including warnings, evasions, changes in the composition of the board since last year).

- Information in the press (about the industry and the company or its competitors).

- Information about environmental or external matter. You should have a good idea as to the type of environmental or competitive factors that affect firms.

More practical indicators

Going concern evaluation

A useful source of guidance on the troubled company is the International Standard on Auditing (ISA) 570, which identifies possible symptoms of going concern problems. Examples are outlined below. Again, if you come across any of these features in a case study the warning bells should start to sound.

Financial issues

- Net liability or net current liability position.

- Necessary borrowing facilities have not been agreed.

- Fixed-term borrowings approaching maturity without realistic prospects of renewal or repayment; or excessive reliance on short-term borrowings to finance long-term assets.

- Major debt repayment falling due where refinancing is necessary to the entity’s continued existence.

- Major restructuring of debt.

- Indications of withdrawal of financial support by debtors and other creditors.

- Negative operating cash flows indicated by historical or prospective financial statements.

- Adverse key financial ratios.

- Substantial operating losses or significant deterioration in the value of assets used to generate cash flows.

- Arrears or discontinuance of dividends.

- Inability to pay creditors on due dates.

- Inability to comply with the terms of loan agreements.

- Change from credit to cash-on-delivery transactions with suppliers.

- Inability to obtain financing for essential new product development or other essential investments.

Operating issues

- Loss of key management without replacement.

- Loss of key staff without replacement.

- Loss of a major market, franchise, licence, or principal supplier.

- Labour difficulties or shortages of important supplies.

- Fundamental changes in the market or technology to which the entity is unable to adapt adequately.

- Excessive dependence on a few product lines where the market is depressed.

- Technical developments which render a key product obsolete.

Other issues

- Non-compliance with capital or other statutory requirements.

- Pending legal or regulatory proceedings against the entity that may, if successful, result in claims that are unlikely to be satisfied.

- Changes in legislation or government policy expected to adversely affect the entity.

Test your understanding 2

You have been asked to determine whether a company is failing.

What areas would your analysis cover?

Corporate reconstruction

Corporate reconstruction of a failing company

Companies in financial distress often undergo corporate reconstructions to enable them to remain in business rather than go into liquidation. Corporate reconstruction in a failing company often involves raising some new capital and persuading creditors/lenders to accept some alternative to the repayment of their debts. This will ensure that the business continues in the short term.

Longer term, the management need to consider whether the reconstruction will help the company develop a sustainable competitive advantage, and provide opportunities for raising further finance.

Options open to failing companies

Options open to failing companies not wishing to go into liquidation, and which allow space for the development of recovery plans, usually include:

- a Company Voluntary Arrangement (CVA)

- an administration order.

Reconstruction of failing companies

- A Company Voluntary Arrangement (CVA)

This is a legally binding arrangement between a company and its creditors. It may involve writing off debt balances on the profit and loss account against shareholders’ capital and creditors’ capital and therefore affects creditors’ rights. However it is designed to ensure that the return to creditors is maximised. It is useful in companies under pressure from cash flow problems.

The procedure is as follows:

– An application is made to the court, asking it to call a meeting between the company and its creditors or a class of creditor, e.g. debenture holders.

– The scheme of reconstruction is put to the meeting and a vote taken.

– If there is 75% in value and including proxies vote in favour the court will be asked to sanction it.

– If the court sanctions it, the scheme is then binding on all the creditors.

- Administration orders

Administration orders were introduced to allow space for a recovery plan to be put in place. The company, its Directors or one of the creditors can apply for an order. The company continues to trade whilst plans are put in place to rescue the company or achieve a better return for the creditors than if the company were liquidated immediately.

The use of an administration order

Consider the case of a manufacturing company which has become insolvent. There are also indications of poor credit control, and production problems including long lead times, high defect rates and high levels of stock. However there is a growing market for the company’s products which are well-designed.

The company was put into administration to allow for a recovery plan to be developed. Its debts were written down and creditors and the bank given equity in the business. New management was brought in which improved the production and financial management and turned round the company which is now profitable.

Test your understanding 3

Why might the decision be made to liquidate a failing company rather than attempt to carry out a reconstruction?

Corporate reconstruction of a solvent company

Corporate reconstructions can also be undertaken by successful companies. The specific objectives of the reorganisation/reconstruction maybe one or more of the following:

- To reduce net of tax cost of borrowing.

- To repay borrowing sooner or later.

- To improve security of finance.

- To make security in the company more attractive.

- To improve the image of the company to third parties.

- To tidy up the statement of financial position.

Options for solvent companies

There are four main types of reorganisation used by solvent companies, depending on the individual situation. These are:

- conversion of debt to equity

- conversion of equity to debt

- conversion of equity from one form to another

- conversion of debt from one form to another.

Reconstruction of solvent companies

- Conversion of debt to equity

The most likely reasons for converting debt to equity are:

– Automatically by holders of convertible debentures exercising their rights.

– In order to improve the equity base of a company. This situation is particularly likely to arise when a company has financed expansion by short-term borrowings. Sooner or later, it will run into working capital problems, and if long-term loan funds are not available (because, for example, they would make the gearing excessively high) the only solution is to issue new shares, possibly by way of a rights issue.

- Conversion of equity to debt

Conversion of equity to debt usually involves the conversion of preference shares to some form of debenture. Although through the eyes of both companies and investors there is little to choose between debentures or preference shares bearing a fixed rate of return, in the eyes of both tax and company law they are very different:

– From the tax point of view, payments to preference shareholders are dividends, and are not, therefore, an allowable charge in computing taxable profits.

– From the legal point of view, conversion of preference shares into debentures constitutes a reduction of capital. Company law provisions relating to redemption of shares must therefore be followed. In accounting terms the broad effect of these provisions is to reduce distributable profits by the nominal value of the preference shares redeemed (by transferring amounts from distributable profit to capital redemption reserve).

- Conversion of equity from one form to another This includes:

– Simplifying the capital structure. It was once common to have a variety of types of share capital, designed to appeal to a variety of investors. This has now become less favoured, and the tendency is to have only one, or at most two, classes of share capital. Conversion of shares from one type to another can only be carried out in accordance with the procedures in the articles, normally approved by a prescribed majority of the class affected, subject to rights of appeal to the court.

– Making shares more attractive to investors, for example by subdivision into smaller units, or conversion into stock.

– Eliminating reserves by issuing fully paid bonus shares. This is very much a tidying up operation, and may be especially useful to remove share premium accounts and capital redemption reserves. Additionally, in a period of inflation, it may be recognising the fact that a substantial part of the revenue reserves could never be paid out as dividends.

- Conversion of debt from one form to another

This procedure might be undertaken to improve security, flexibility or cost of borrowing. For example:

– Security – Consider the example of a company financing itself out of creditors and overdraft facilities, neither of which give any security. Rather than a rights issue, converting the creditors to long-term loans, e.g. debentures, would be equally satisfactory in that it would give security as to the source of funds.

– Flexibility – Again, a company financing itself out of short-term borrowings has little room to manoeuvre. Flexibility could be improved by arranging more permanent financing. Alternatively, a company already borrowing to the limits of its ability could reduce its borrowings and improve flexibility by using other sources of finance – leasing for example.

– Cost – Some loan finance is cheaper than others for example secured loans compared with unsecured loans. An opportunity may arise to shift from a relatively high cost to a relatively low cost source of funds.

The legal aspects of corporate reconstruction

Reconstruction schemes may be undertaken in companies which are healthy or those in financial difficulties.

The boundary line between these two types of scheme is not clear cut.

Some provisions of company law can be used by both types of company.

For example the capital reduction provisions of S641 in the UK Companies Act 2006 can be used by a company to tidy up its statement of financial position reserves or to write off debt balances arising from trading losses so that further finance can be obtained.

6 Devising a corporate reconstruction scheme

General principles in devising a scheme

In most cases the company is ailing:

- Losses have been incurred with the result that capital and long-term liabilities are out of line with the current value of the company’s assets and their earning potential.

- New capital is normally desperately required to regenerate the business, but this will not be forthcoming without a restructuring of the existing capital and liabilities.

The general procedure to follow would be:

- Write off fictitious assets and the debit balance on profit and loss account. Revalue assets to determine their current value to the business.

- Determine whether the company can continue to trade without further finance or, if further finance is required, determine the amount required, in what form (shares, loan stock) and from which persons it is obtainable (typically existing shareholders and financial institutions).

- Given the size of the write-off required and the amount of further finance required, determine a reasonable manner in spreading the write off (the capital loss) between the various parties that have financed the company (shareholders and creditors).

- Agree the scheme with the various parties involved.

The impact on stakeholders

The interests of a number of different stakeholder groups must be taken into account in a reconstruction. A reconstruction will only be successful if it manages to balance the different objectives (risk and potential return) of:

- ordinary shareholders

- preference shareholders

- creditors, including trade payables, bankers and debenture holders.

In a failing company, the reconstruction should be organised so that the main burden of any loss falls on the ordinary shareholders.

Test your understanding 4

Why is it important to consider the interests of shareholders in developing a reconstruction scheme?

Different stakeholder requirements

- Solvent companies often enter reconstruction schemes to improve their ability to raise finance in the future by making security in the company more attractive or to improve the image of the company to third parties. The view taken of the scheme by banks and investors is therefore vital in ensuring that this aim is achieved.

- Banks have been criticised in the past for being too quick to close down failing companies in order to protect their investment at the expense of others – it is important that they are initially supportive and allow time for decisions about the company’s future to be made with the full co-operation of all stakeholders.

- The design of a reconstruction scheme for a failing company needs to take into account the interests of:

– ordinary shareholders

– preference shareholders

– creditors.

- In a failing company the main burden of the losses should be borne primarily by the ordinary shareholders, as they are last in line in repayment of capital on a winding up. In many cases, the capital loss is so great that they would receive nothing upon a liquidation of the company. They must, however, be left with some remaining stake in the company if further finance is required from them.

- Preference shares normally give holders a preferential right to repayment of capital on a winding up. Their loss should be less than that borne by ordinary shareholders. They may agree to forgo arrears of dividends in anticipation that the scheme will lead to a resumption of their dividends.

- If preference shareholders are expected to suffer some reduction in the nominal value of their capital, they may require an increase in the rate of their dividend or a share in the equity, which will give them a stake in any future profits.

- Creditors, including debenture and loan stock-holders may agree to a reduction in their claims against the company if they anticipate that full repayment would not be received on liquidation. Like preference shareholders, an incentive may be given in the form of an equity stake.

In addition trade creditors may also agree to a reduction if they wish to protect a company which will continue to be a customer to them.

Test your understanding 5 – Wire Construction Case Study Part 1 Case study – Wire Construction

Wire Construction has suffered from losses in the last three years. Its statement of financial position (balance sheet) as at 31 December 20X1 shows:

| Non-current assets | $ | |

| Land and buildings | 193,246 | |

| Equipment | 60,754 | |

| Investment | 27,000 | |

| ––––––– | ||

| Current assets | 281,000 | |

| Inventory | 120,247 | |

| Receivables | 70,692 | |

| ––––––– | 190,939 | |

| ––––––– | ||

| Total assets | 471,939 | |

| Equity and liabilities | ––––––– | |

| Ordinary shares – $1 | 200,000 | |

| 5% Cumulative preference shares – $1 | 70,000 | |

| Profit and loss | (39,821) | |

| ––––––– | ||

| 230,179 | ||

| Non-current liabilities | ||

| 8% Debenture 20X4 | 80,000 | |

| Current liabilities | ||

| Trade payables | 112,247 | |

| Interest payable | 12,800 | |

| Overdraft | 36,713 | |

| ––––––– | 161,760 | |

| ––––––– |

471,939

–––––––

Sales have been particularly difficult to achieve in the current year and inventory levels are very high. Interest has not been paid for two years. The debenture holders have demanded a scheme of reconstruction or the liquidation of the company.

Required:

Show the likely position of the key stakeholders (ordinary shareholders, preference shareholders and debenture holders) if the firm goes into liquidation.

Assume that

- The investment is to be sold at the current market price of $60,000.

- 10% of the receivables are to be written off.

- The remaining assets were professionally valued as follows:

| $ | |

| Land | 80,000 |

| Building | 80,000 |

| Equipment | 30,000 |

| Inventory and work-in-progress | 50,000 |

Illustration 1 – Wire Construction Part 2

Continuing with the information on Wire Construction from the previous TYU.

During a meeting of shareholders and directors, it was decided to carry out a scheme of internal reconstruction. The following scheme has been proposed:

- Each ordinary share is to be re-designated as a share of 25c.

- The existing 70,000 preference shares are to be exchanged for a new issue of 35,000 8% cumulative preference shares of $1 each and 140,000 ordinary shares of 25c each.

- The ordinary shareholders are to accept a reduction in the nominal value of their shares from $1 to 25c, and subscribe for a new issue on the basis of 1 for 1 at a price of 30c per share.

- The debenture holders are to accept 20,000 ordinary shares of 25c each in lieu of the interest payable. It is agreed that the value of the interest liability is equivalent to the nominal value of the shares issued. The interest rate is to be increased to 9.5% and the repayment date deferred for three years. A further $9,000 of this 9.5% debenture is to be issued and taken up by the existing holders.

- The profit and loss account balance is to be written off.

- The bank overdraft is to be repaid.

- It is expected that, due to the refinancing, operating profits will be earned at the rate of $50,000 p.a. after depreciation but before interest and tax.

- Corporation tax is 21%.

Required:

Prepare the statement of financial position (balance sheet) of the company, assuming that the proposed reconstruction has just been undertaken.

Solution

Tutorial note: In a question like this, do not waste time producing a statement of financial position unless it is specifically asked for by the examiner.

Statement of financial position at 1 January 20X2 (after reconstruction)

| Non-current assets | $ | $ | ||

| Land at valuation | 80,000 | |||

| Building at valuation | 80,000 | |||

| Equipment at valuation | 30,000 | |||

| ––––––– | ||||

| Current assets | 190,000 | |||

| Inventory | 50,000 | |||

| Receivables (70,692 × 90%) | 63,623 | |||

| Cash (W1) | 92,287 | |||

| –––––– | 205,910 | |||

| ––––––– | ||||

| 395,910 | ||||

| ––––––– | ||||

| Called up share capital | $ | $ | ||

| Issued ordinary shares of 25c each (W2) | 140,000 | |||

| Issued 8% cumulative preference shares of | ||||

| $1 each (W2) | 35,000 | |||

| Share premium account (W2) | 17,800 | |||

| Capital reconstruction account (balancing figure) | 1,863 | |||

| ––––––– | ||||

| 194,663 | ||||

| Non-current liabilities: 9.5% Debenture 20X7 | 89,000 | |||

| Current liabilities: Trade payables | 112,247 | |||

| ––––––– | ||||

| Total equity and liabilities | 395,910 | |||

| ––––––– | ||||

| Workings | |

| (W1) Cash | |

| New share issue – Ords | $ |

| 200,000 × 30c | 60,000 |

| New debentures | 9,000 |

| Sale of investment | 60,000 |

| ––––––– | |

| 129,000 | |

| Less: Overdraft | 36,713 |

| ––––––– | |

| 92,287 | |

| ––––––– |

(W2) Shareholdings

| Ords | Prefs | |||

| No. | $ | No. | $ | |

| Per SOFP | 200,000 | 200,000 | 70,000 | 70,000 |

| Redesignation | 50,000 | |||

| Exchange | 140,000 | 35,000 | (35,000) | (35,000) |

| New issue | 200,000 | 50,000 | ||

| Debenture interest | 20,000 | 5,000 | ||

| (12,800 – 5,000) | ||||

| ––––––– | ––––––– | –––––– | –––––– | |

| 560,000 | 140,000 | 35,000 | 35,000 | |

| ––––––– | ––––––– | –––––– | –––––– | |

Share

premium

$

10,000

7,800

––––––

17,800

––––––

Tutorial note: As $12,800 of debenture interest is to be cancelled for $5,000 nominal of ordinary shares the excess is share premium (i.e. the consideration for the shares is deemed to be the liability removed).

Test your understanding 6 – Wire Construction Part 3

Advise the shareholders and debenture-holders as to whether they should support the Wire Construction reconstruction.

More detail on the Wire Construction Case Study

Reconstruction account, relating to the second part of the case study

Note: The capital reconstruction account can be proved as follows:

| Book value: | Revised values: | ||

| Non-current assets | 281,000 | Land and buildings | 160,000 |

| Inventory | 120,247 | Equipment | 30,000 |

| Receivables written off | Investment | 60,000 | |

| 10% × 70,692 | 7,069 | Inventory | 50,000 |

| Profit and loss balance | 39,821 | Share capital | |

| reduced | |||

| 200,000 × 75c | 150,000 | ||

| Balance – Capital | |||

| reserve | 1,863 | ||

| ––––––– | ––––––– | ||

| 450,000 | 450,000 | ||

| ––––––– | ––––––– |

Detailed advice to shareholders and debenture holders, relating to the third part of the case study

It follows that the scheme must be favourable to the debenture-holders if it is to have success. The holders are being offered an increased rate of interest but an extended repayment date.

| The expected interest cover is reasonable: | |

| $ | |

| Expected profits | 50,000 |

| Interest | |

| 9.5% × 89,000 | 8,455 |

| Interest cover = 5.9 |

In financial terms it is a matter of comparing the prospective rate of interest with interest rates currently available elsewhere.

The preference shareholders are having half of their investment turned into equity. They will have 140,000/560,000 × 100 = 25% of the ordinary share capital. In addition they will have an increased dividend rate and are not required to contribute any further capital.

The ordinary shareholders retain part of their stake in the company if they participate 200,000/560,000 = 36% without any further cash investment. The further cash investment required of $50,000 leaves them with the majority holding.

| The expected available earnings will be: | |

| $ | |

| Profit | 50,000 |

| Interest | (8,455) |

| –––––– | |

| 41,545 | |

| Tax at 21% | (8,724) |

| –––––– | |

| 32,821 | |

| Preference dividend 35,000 × 8% | (2,800) |

| –––––– | |

| Available to equity | 30,021 |

| –––––– | |

| EPS 30,021/560,000 × 100 = | 5.4c |

| –––––– |

However, as the shareholders would receive nothing on a liquidation, the additional expected return to them is twice 5.4c per share i.e.:

On old shareholding

200,000 × 5.4c

On new shareholding

200,000 × 5.4c

This therefore seems a reasonable proposition to the ordinary shareholders.

Test your understanding 7 – Another reconstruction example

BDJR Computers Global is a company that manufactures a range of personal computers that are sold to retailers, and also directly to individuals and businesses through online sales.

Due to a number of technical problems the company’s sales have fallen significantly over the last year resulting in an operating loss of $160,000. The company has, as a result, built up losses on its retained earnings and there is a significant risk of insolvency.

To avoid this, the company’s financial advisers have proposed a scheme of reconstruction.

Balance Sheet at 31/12/20X9 (statement of financial position)

| Assets | $000 | $000 |

| Non-current assets | 1,100 | |

| Current assets | ||

| Inventory | 410 | |

| Receivables | 220 | |

| Cash | 25 | |

| Net Current Assets | ––––– | 655 |

| Total Assets | ––––– | |

| 1,755 | ||

| Equity and Liabilities | ––––– | |

| Share Capital ($1 shares) | 200 | |

| Retained Earnings | (50) | |

| Total Equity | ––––– | |

| 150 | ||

| Non-current liabilities – Bank loan | 1,200 | |

| Current liabilities | ||

| Payables | 205 | |

| Overdraft | 200 | |

| ––––– | 405 | |

| Total Equity and Liabilities | ––––– | |

| 1,755 | ||

| ––––– |

Notes:

- If the company was liquidated all of the assets could be sold for their book values except for inventory. Following a review it was discovered that $220k of the inventory is obsolete but the remainder could be sold for book value. In addition $90k of the receivables is irrecoverable.

- To be successful a scheme of reconstruction would need to raise $195k of cash to invest in new manufacturing processes.

- Given the risk attached to the company any providers of new equity capital will require a return of at least 18%.

- The current interest rates are 8% on the bank loan and 6% on the overdraft. The bank loan is secured.

The following scheme of reconstruction is proposed:

- The nominal value of each existing share will be reduced to 50c.

- Goodwin Bank (who provide both the overdraft and loan) will convert half of the overdraft and 1/3 of the loan into a total of 200,000 new shares.

- New finance of $400k will be raised from a venture capital company, PC ventures, who will buy new shares for $1.25 per share. In addition to investing in the new manufacturing process the finance will also be used to repay the payables.

- Following the reconstruction it is expected that the company will generate $320K of profit before interest and tax per annum. Tax is payable at 28%. Assume no tax losses.

Required:

- Determine how much each of the original investors in likely to get in the event of a liquidation.

- Following the reconstruction calculate the expected EPS, and the return on equity to the venture capital company, and advise as the whether the venture capital company is likely to invest in BDJR computers.

- From the post-reconstruction EPS calculation above calculate the effective return that the bank is likely to receive on the capital converted into equity.

- Determine whether the existing ordinary shareholders, and the bank, are likely to accept the scheme.

Assessing the impact of the reconstruction scheme

The examples above have shown that the key to assessing the impact of a reconstruction scheme is to look at the likely impact on major stakeholders. In order to do this effectively, it is often useful to assess the likely impact of the scheme on the company’s forecast:

- statement of financial position (SOFP)

- earnings (in total and/or per share).

Several recent past exam questions have first asked students to calculate the impact of a reconstruction scheme on the SOFP and earnings, and then to comment on the implications.

A tabular approach can help to present the answer in an efficient and easily understandable way.

Tabular method

Step 1: Set up a table with the current forecast earnings and SOFP in the first column. Set up columns to the right for each of the suggested reconstruction options.

Step 2: Deal with each of the suggested reconstruction options separately – start with the one that sounds most straightforward.

Step 3: Deal with the simple parts of the reconstruction first. Usually these will be the SOFP figures e.g. if the plan is to increase debt finance by $5 million, simply add $5 million to the non-current liabilities and write the updated figure in the correct column.

Step 4: Now move on to the more tricky parts. Usually these will be the adjustments to earnings caused by (one or more of) paying more interest on the higher amount of debt finance identified in Step 3, generating more income from assets purchased and identified in Step 3, generating less income because assets have been disposed of and identified in Step 3.

Step 5: Having calculated the revised forecast earnings figure in Step 4, adjust the forecast retained earnings (reserves) in the SOFP to reflect this.

Step 6: Balance off the SOFP by entering anything that is still unknown as a balancing figure.

Step 7: Repeat steps 3 to 6 for each of the reconstruction options.

Test your understanding 8

Ray Co is a company with a diversified range of business units. One of its business units, a training business, is underperforming. The Finance Director estimates that this business unit could be disposed of by selling its non-current assets for their book value of $25 million.

At the recent Board meeting, the directors discussed the possible disposal, and two proposals for the use of the $25 million proceeds:

Proposal 1: Use half the proceeds to pay off some debt finance, and the other half to invest in some new non-current assets for an existing publishing business unit.

Proposal 2: Use the full amount to purchase some new non-current assets and set up a new business unit in the advertising industry.

At the end of the Board meeting, the Finance Director was asked to prepare some calculations to show the likely impact of these two proposals on Ray Co’s forecast statement of financial position and forecast earnings for the coming year.

Ray Co, financial information

Extract from the forecast statement of financial position for next year

| $000 | |

| Non-current assets | 92,650 |

| Current assets | 16,620 |

| ––––––– | |

| Total assets | 109,270 |

| Equity and liabilities | ––––––– |

| Share capital – $1 par value | 50,000 |

| Reserves | 20,550 |

| ––––––– | |

| Total equity | 70,550 |

| Non-current liabilities | 30,000 |

| Current liabilities | 8,720 |

| ––––––– |

109,270

–––––––

Ray Co’s forecast after-tax profit for next year is $15.6 million.

Other information:

- The training business contributes 10% of Ray Co’s overall after-tax profit.

- Ray Co pays tax at a rate of 20% per year and its after-tax return on the publishing business unit is estimated at 8%. The after-tax return on the advertising investment is expected to be 13%.

- The non-current liabilities are bank loans with a fixed interest rate of 6%.

Required:

- Estimate the impact of the two proposals on next year’s forecast earnings and forecast financial position.

- Evaluate the decision to sell the training business unit, and advise the Board of Directors which (if either) proposal should be accepted.

Business reorganisation methods

Unbundling companies

Unbundling is the process of selling off incidental non- core businesses to release funds, reduce gearing and allow management to concentrate on their chosen core businesses. The main aim is to improve shareholder wealth. Unbundling can take a number of forms:

- Spin-offs, or demergers, in which the ownership of the business does not change, but a new company is formed with shares in the new company owned by the shareholders of the original business. This results in two or more companies instead of the original one.

- Sell-offs, which involves the sale of part of the original company to a third party, usually in return for cash.

- Management buyouts, in which the management of the business acquires a substantial stake in and control of the business which they managed.

- Liquidation, when the entire business is closed down, the assets sold and the proceeds distributed to shareholders. This is done when the owners of the business no longer want it or the business is not seen as viable.

The rest of this chapter explains these unbundling options in detail.

Test your understanding 9

Explain why shareholders might support the unbundling of a diversified organisation.

Spin-offs or demergers

Demergers

The aim of a demerger is to create separate businesses which together have a higher value than the original company. Following a demerger:

- shareholders own the same proportion of shares in the new business or businesses as they did in the previous one

- each company owns a share of the assets of the original company

- the new company or companies generally have new management who can take the individual companies in diverging directions; and each company could eventually be sold separately

- the original company may no longer exist, with all its assets distributed to the new business.

Sell-offs

A company may sell-off parts of the business for a number of reasons, such as:

- to raise cash

- to prevent a loss-making part of the business from lowering the overall performance business

- to concentrate on the core areas of the business

- to dispose of a desirable part of the business to protect the rest from the threat of a takeover.

Management buy-outs

What is a management buy-out?

Overall the distinguishing feature of an MBO is that a group of managers acquires effective control and substantial ownership and forms an independent business. Several variants of an MBO may be identified and are explained below:

- Management buy-out – where the executive managers of a business join with financing institutions to buy the business from the entity which currently owns it. The managers may put up the bulk of the finance required for the purchase.

- Leveraged buyout – where the purchase price is beyond the financial resources of the managers and the bulk of the acquisition is financed by loan capital provided by other investors.

- Employee buyout – which is similar to the above categories but all employees are offered a stake in the new business.

- Management buy-in – where a group of managers from outside the business make the acquisition.

- Spin-out – this is similar to a buyout but the parent company maintains a stake in the business.

The difference between a management buy-out and a management buy-in

A management buy-out (MBO) involves the purchase of a business by the management team running that business.

However, a management buy-in (MBI) is the purchase a business by a management team brought in from outside the business.

The benefits of a MBO relative to a MBI (to the company being acquired) are that the existing management is likely to have detailed knowledge of the business and its operations. Therefore they will not need to learn about the business and its operations in a way which a new external management team may need to. It is also possible that a MBO will cause less disruption and resistance from the employees when compared to a MBI. If the former parent company wants to continue doing business with the new company after it has been disposed of, it may find it easier to work with the management team which it is more familiar with. The internal management team may be more focused and have better knowledge of where costs can be reduced and sales revenue increased, in order to increase the overall value of the company.

The drawbacks of a MBO relative to a MBI (to the company being acquired) may be that the existing management may lack new ideas to rejuvenate the business. A new management team, through their skills and experience acquired elsewhere, may bring fresh ideas into the business. It may be that the external management team already has the requisite level of finance in place to move quickly and more decisively, whereas the existing management team may not have the financial arrangements in place yet. It is also possible that the management of the parent company and the company being sold off have had disagreements in the past and the two teams may not be able to work together in the future if they need to.

Example of a MBO (Springfield ReManufacturing Corporation)

One of the most well-known examples of a management buy-out is the Springfield ReManufacturing Corporation (SRC) in 1982. Prior to the buy-out the company was the Springfield, Missouri unit of International Harvester, a manufacturer of agricultural and construction equipment in the USA. The unit remanufactured components for the company’s construction division.

In 1981 although the unit was profitable, International Harvester was in significant difficulties and decided it no longer needed the Springfield unit. However a group of managers led by Jack Stack, now CEO of SRC Holdings Corporation, kept the plant running and eventually bought the unit.

SRC Holdings now owns many other successful companies.

Reasons for a management buy-out

Opportunities for MBOs may arise for several reasons:

- The existing parent company of the ‘victim’ firm may be in financial difficulties and therefore require cash.

- The subsidiary might not ‘fit’ with the parent’s overall strategy, or might be too small to warrant the current management time being devoted to it.

- In the case of a loss-making part of the business, selling the subsidiary to its managers may be a cheaper alternative than putting it into liquidation, particularly when redundancy and other wind-up costs are considered.

- The victim company could be an independent firm whose private shareholders wish to sell out. This could be due to liquidity and tax factors or the lack of a family successor to fill the owner-manager role.

Advantages of buy-outs to the disposing company

There are a number of advantages to the parent company:

- If the subsidiary is loss-making, sale to the management will often be better financially than liquidation and closure costs.

- There is a known buyer.

- Better publicity can be earned by preserving employee’s jobs rather than closing the business down.

- It is better for the existing management to acquire the company rather than it possibly falling into the hands of competitors.

Advantages to the acquiring management

The advantages to the acquiring management are that:

- it preserves their jobs

- it offers them the prospect of significant equity participation in their company

- it is quicker than starting a similar business from scratch

- they can carry out their own strategies, no longer having to seek approval from head office.

Issues to be addressed when preparing a buy-out proposal

MBOs are not dissimilar to other acquisitions and many of the factors to be considered will be the same:

- Do the current owners wish to sell? The whole process will be much easier (and cheaper) if the current owners wish to sell. However, some buy-outs have been concluded despite initial resistance from the current owners, or in situations of bids for the victim from other would-be purchasers.

- Will the new business be profitable? Research shows that MBOs are less likely to fail than other types of new ventures, but several have collapsed. As the new owners the management team must ensure that the business will be a long-run profit generator. This will involve analysing the performance of the business and drawing up a business plan for future operations.

- If loss-making, can the new managers return it to profitability? Many loss-making firms have been returned to profitability via management buyouts. Managers of a subsidiary are in a unique position to appreciate the potential of a business and to know where cost savings can be made by cutting out ‘slack’.

- What will be the impact of loss of head office support? On becoming an independent firm many of the support services may be lost. Provision will have to be made for support in areas such as finance, computing, and research and development. Although head office fees might be saved after the buyout these support services can involve considerable expense when purchased in the outside market.

- What is the quality of the management team? The success of any MBO will be greatly influenced by the quality of the management team. It is important to ensure that all functional areas are represented and that all managers are prepared to take the required risks. A united approach is important in all negotiations and a clear responsibility structure should be established within the team.

- What is the price? The price paid will be crucial in determining the long-term success of the acquisition. Care must be taken to ensure that all relevant aspects of the business are included in the package. For example, trademarks and patents may be as important as the physical assets of the firm. In a similar way responsibilities for costs such as redundancy costs must be clearly defined.

- Is the deal in the best interests of shareholders? Managers known to the existing owners may be able to secure the buyout at a favourable price, and the final price paid will be a matter for negotiation. However, the current directors of the firm have a responsibility to shareholders to obtain the best deal possible, which may mean a full ‘commercial’ price being paid for the victim company.

Sources of finance for buy-outs

For small buy-outs the MBO, the price may be within the capabilities of the management team, but the acquiring group usually lack the financial resources to fund the acquisition. Several institutions specialise in providing funds for MBOs. These include:

- the clearing banks

- pension funds and insurance companies

- merchant banks

- specialist institutions such as the 3i group and Equity Capital for Industry

- government agencies and local authorities, for example regional development agencies.

Different types of finance

The types of finance and the conditions attached vary between the institutions. Points to be considered include:

- The form of finance – Some institutions will provide equity funds. However, more commonly loan finance will be advanced. Equity funds will dilute the management team’s ownership but on the other hand high gearing could put substantial strain on the firm’s cash flow. Leveraged buyouts, with gearing levels up to 20:1, have been known.

- Duration of finance – Some investors will require early redemption of loans and will provide funds in the form of redeemable loan stock or preference shares. Others may accept longer-term involvement and look to an eventual public flotation as an exit from the business.

- The involvement of the institution – Some institutions may require board representation as a condition of providing funds.

- Ongoing support – The management team should also consider the institution’s willingness to provide funds for later expansion plans. Some investors also offer other services such as management consultancy to their clients.

- Syndication – In large buyouts it is possible that a syndicate of institutions may be required to provide the necessary funds.

- The need for financial input from the management team – All institutions will look for a ‘significant’ input of finance from the management team relative to their personal wealth as a demonstration of their commitment. Managers can expect to have to plough in their redundancy payments, take second mortgages on their homes and often provide personal guarantees on loans.

- The need for a business plan – Institutional investors will also expect to see a well-prepared business plan and usually an investigating accountant and a technical advisor will be employed to investigate the proposal.

- Other sources of finance – The management team can also look for other sources of finance to assist in the MBO. Hire purchase or leasing of specific assets may ease initial cash flow problems. Government grants might be available for certain firms, and the managers’ and employees’ pension scheme may be available to provide some of the required finance.

MBO terminology

The management buy-out industry has developed a range of colourful jargon terms over its period of existence, such as:

- BIMBO – A deal involving both a buy-in by outside managers and a buy-out by current managers has been coined a bimbo by Investors in Industry (the 3i group) and unfortunately the name has stuck.

Around 50% of recent deals take this form.

- Caps, floors and collars are limits to which the interest rate charged in a leveraged buy-out can respectively rise, fall and range between.

- Junk bonds are tradeable high yielding unsecured debt certificates issued by companies in US leveraged buy-outs. Their equivalent in the UK is mezzanine finance, though this is less easily traded than junk bonds since it is not usually issued in certificate form.

- Lemons are deals that go wrong.

- Plums are successful deals.

- The living dead are companies which just earn enough cash to pay the interest on their borrowings, but no more. They can continue indefinitely, but are never expected to flourish.

- A ratchet arrangement permits managers to be allocated a larger share of the company’s equity if the venture performs well. It is intended as an incentive arrangement to encourage managers to be committed to the success of the company.

Assessing the viability of buy-outs

Both the management buy-out team and the financial backers will wish to be convinced that their proposed MBO will succeed. It is important to ask the following questions:

- Why do the current owners wish to sell? If the owners are trying to rid themselves of a loss-making subsidiary, are the new management being over-confident in believing that they can turn it round into profitability?

- Does the proposed management team cover all key functions? If not, new appointments should be made as soon as possible.

- Has a reliable business plan been drawn up, including cash flow projections, and examined by an investigating accountant?

- Is the proposed purchase price too high?

- Is the financing method viable? The trend is now away from highly geared buy-outs.

Test your understanding 10

Identify some advantages and disadvantages of management buy-outs.

Numerical example of a management buy-out Example question – Management buy-out

- The following information relates to the proposed financing scheme for a management buy-out of a manufacturing company.

| Share capital held by | % | €000 | |

| Management | 40 | 100 | |

| Institutions | 60 | 150 | |

| ––––– | |||

| 10% redeemable preference shares | 250 | ||

| 1,200 | |||

| (redeemable in ten years’ time) | |||

| ––––– | |||

| 1,450 | |||

| Loans | 700 | ||

| Overdraft facilities | 700 | ||

| ––––– | |||

| 2,850 | |||

| ––––– | |||

Loans are repayable over the next five years in equal instalments.

They are secured on various specific assets, including properties.

Interest is 12% pa.

The manufacturing company to be acquired is at present part of a much larger organisation, which considers this segment to be no longer compatible with its main line of business. This is despite the fact that the company in question has been experiencing revenue growth in excess of 10% pa.

The assets to be acquired have a book value of €2,250,000, but the agreed price was €2,500,000.

You are required to write a report to the buy-out team, appraising the financing scheme.

- What problems are likely to be encountered in assembling a financing package in a management buy-out of a service company as opposed to a manufacturing company?

Solution

- Report

To: Buy-out team

From: Consulting accountant

Date: X-X-20XX

Subject: MBO Financing Scheme Overview

The financing scheme involves the purchase of assets with a net book value of €2,250,000 for an agreed price of €2,500,000. The finance that will be raised will provide funds of €2,850,000 in the form of:

| €000 | |

| Equity | 250 |

| Preference shares | 1,200 |

| Loan | 700 |

| Overdraft | 700 |

| ––––– |

2,850

–––––

Of the funds raised only €350,000 will be available to the business after the purchase price has been paid. This will be in the form of unused overdraft facilities.

Gearing

As is common to MBOs the gearing level will be very high. There is only €250,000 of equity compared to €2,250,000 of debt finance (including the preference shares and excluding the unused element of the overdraft). The gearing level will mean that the returns to equity will be risky, but the buyout team own 40% of a €2.5 million company for an investment of only €100,000. The rewards are potentially very high.

One consequence of the level of gearing is that it will be difficult to raise any additional finance. There are unlikely to be any assets that are not secured, and in any case the level of interest and loan repayments would probably prohibit further borrowing.

Cash commitments

The annual cash commitments from the financing structure are summarised below:

- Loan repayments

Annual payments will have to be made in the repayment of capital and interest on the €700,000 loan. The annual amount will be:

€700,000/3.605* = €194,175

- The cumulative discount factor for 5 years at 12%.

- Redeemable preference shares

The redeemable preference shares will be either cumulative or non-cumulative. Assuming that they are cumulative €120,000 will, on average, have to be paid every year. There is a little flexibility in that if the dividend cannot be met it can be postponed (but not avoided).

The redeemable preference shares will have to be repaid after 10 years. This can either be provided for over the 10 years, or an alternative source of finance found to replace the funds.

Assuming that they will be required to be provided for according to the terms of the financing package this will require a commitment of €120,000 p.a.

- Overdraft

The element of the overdraft used to finance the purchase price is effectively a source of long term finance. The rate of interest is not known but if we make the (unrealistic) assumption that it is also at 12%, then the €350,000 drawn down will cost €42,000 pa. In total there will be a commitment to pay approximately €476,000 p.a.

This will be the first priority of the new company. The management team will need to generate sufficient funds from the only available source, operations, in order to meet this commitment.

Other cash requirements

Apart from the need to generate cash to satisfy the requirements of the financing scheme the company will also need to generate funds to invest in working capital and fixed assets as required. At the moment these capital requirements are unknown. In the context of 10% annual growth in revenue, however, they might exceed the unused element of the overdraft facility.

Institutional involvement

By virtue of their stake in the company of 60% of the equity the financial institutions hold the controlling stake. This will be enhanced by their position as the providers of the remainder of the finance. Consequently the institutions will able to determine many aspects of the company’s management, including the appointment of directors. The institutions are likely to have two overriding objectives:

- The security of loan and interest repayments. Any breach of the loan arrangements might trigger the appointment of administrators or receivers, and the institutions’ investment would almost certainly be lost.

- Realising their equity investment. The institutional investors will probably expect to realise their investment in a relatively short time frame. This is commonly set at between 5 and 7 years.

Profit growth

Apart from the requirement to generate cash as noted above the company must also generate steady profit growth. The institutional investors will require a history of profit growth in order to enable the sale of their stake through either flotation or a trade sale.

Conclusion

The financing scheme will place a heavy cash burden on the company, particularly in the early years. The involvement of the institutions will perhaps prove unwelcome, but the MBO would be impossible without accepting it.

- There are three main problems particular to arranging a finance package for a service company.

- The lack of tangible assets

Because MBOs normally have to be highly geared there is a requirement to provide security for the loans in a package. Service companies commonly have a very low level of tangible assets. It will therefore be difficult to attract much debt finance.

- ‘People’ businesses

The success of service companies depends on their staff. Institutions tend to view such success with suspicion because people, unlike plant and machinery, can resign. Unless the people in question are tied into the company within the MBO financing package by, for example, insisting on their investing in equity there is little guarantee that they will stay with the company.

- Working capital

The nature of most service businesses is that they have unusually high working capital requirements. The main expense for a service company is staff costs. It is almost impossible to take extended credit from staff without losing their services. The supplies of service companies often involve a long period of work before customers can be billed. Consequently, a finance package would have to provide for the working capital, and working capital finance is particularly risky because it is difficult to secure and so may be equally difficult to raise.

Evaluating the benefits of reorganisations

Concentration of growth and maximisation of shareholder value

Following the unbundling of a company the resulting value of the new businesses can exceed that of the original business. This suggests that the shares in the original business were selling for less than their potential value and can be for a number of reasons:

- The splitting-off of non-core activities from the rest of the business may increase the visibility of an under-valued asset which is then valued more highly by the market.

- Businesses may be valued more highly in the hands of the new managers than under the previous management.

- The sale of less profitable parts of the business may be viewed favourably by the market, result in an increased valuation for the remainder.

- The performance of the individual businesses may improve, also resulting in a higher valuation.

Reduction in complexity and improved managerial efficiency

Since the 1980s, increasing numbers of demergers and sell-offs have taken place in order to reduce the complexity of the organisation:

- Diversified businesses are complex to manage. As the pace of change and uncertainty facing organisations has increased, the complexity of large businesses becomes more difficult to cope with and absorbs management time and energy which is diverted from the business itself.

- Smaller companies tend to be more flexible and respond more easily to change.

- Following a demerger, the new companies have a clearer, more focused management structure.

- Improved managerial effectiveness also results from the splitting off of non-core businesses as managers are free to concentrate on what they do best.

- Changes in the market can also mean that benefits of synergy no longer exist, and there is no longer any business reason for the organisation to retain unrelated businesses.

The release of financial resources for new investment

Unbundling parts of the company can also release financial resources:

- selling a loss-making part of the business which is absorbing funds can release cash to invest in the core businesses or new activities

- a reduction in the size and complexity of the organisation can reduce the central management costs, freeing up resources

- unbundling generates a lump sum in proceeds which can be invested in a specific project.

Illustration

In October 2006 GUS plc, a major UK retail and business services conglomerate, completed the process of demerger into three separate businesses. Burberry, a luxury brand, was demerged first, and the remaining company was demerged in October 2006 into Experian, a provider of analysis and information services, and Home Retail Group, a major home and general retailer.

This demerger was the culmination of a strategy to maximise shareholder wealth by focusing on a small number of high-growth businesses. Other parts of the business were sold off to raise funds for reinvestment. Among the reasons given for the demerger were:

- the lack of synergy between the businesses

- separate opportunities for investment for shareholders

- allowing the independent businesses to pursue individual strategies and benefit from a better management focus.