Mergers and acquisitions – The terms explained

Terminology

The term ‘merger’ is usually used to describe the joining together of two or more entities.

Strictly, if one entity acquires a majority shareholding in another, the second is said to have been acquired (or ‘taken over’) by the first. If the two entities join together to submerge their separate identities into a new entity, the process is described as a merger.

In fact, the term ‘merger’ is often used even when an acquisition/takeover has actually occurred, because of the cultural impact on the acquired entity – the word merger makes the arrangement sound like a partnership between equals.

Types of merger/acquisition

Types of merger

The arguments put forward for a merger may depend on its type:

- Horizontal integration

- Vertical integration

- Conglomerate integration.

Horizontal integration

Two companies in the same industry, whose operations are very closely related, are combined, e.g. Glaxo with Welcome and the banks and building societies mergers, e.g. Lloyds TSB and HBOS.

Main motives: economies of scale, increased market power, improved product mix.

Disadvantage: can be referred to relevant competition authorities.

Vertical integration

Two companies in the same industry, but from different stages of the production chain merger.

e.g. major players in the oil industry tend to be highly vertically integrated.

Main motives: increased certainty of supply or demand and just -in-time inventory systems leading to major savings in inventory holding costs.

Conglomerate integration

A combination of unrelated businesses, there is no common thread and

the main synergy lies with the management skills and brand name,

e.g. General Electrical Corporation and Tomkins (management) or Virgin

(brand).

Main motives: risk reduction through diversification and cost reduction (management) or improved revenues (brand).

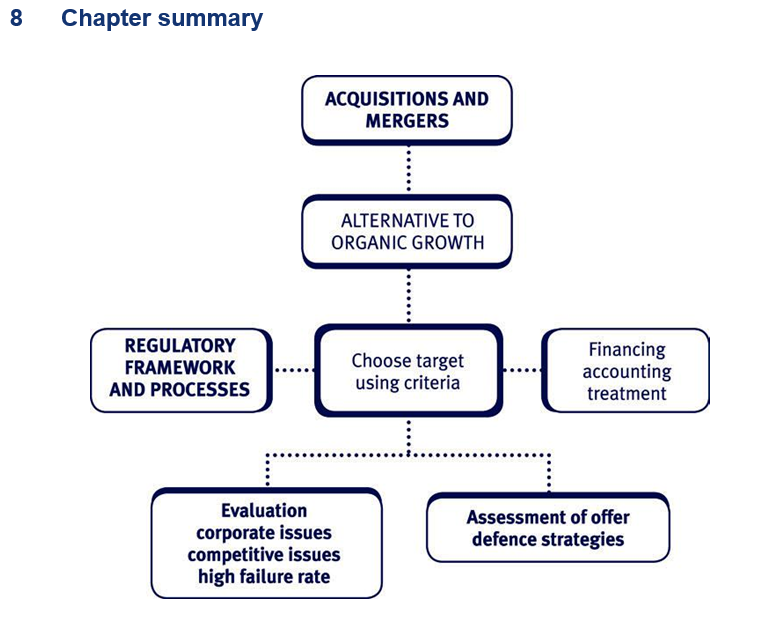

2 The reasons for growth by acquisition or merger

Key reasons for acquisition

The potential for synergy is often given as the main reason for growth by acquisition. However, other more specific reasons are:

- Increased market share/power

- Economies of scale

- Combining complementary needs

- Improving efficiency

- A lack of profitable investment opportunities (surplus cash)

- Tax relief

- Reduced competition

- Asset-stripping

- Diversification – to reduce risk

- Shares of the target are undervalued.

More on the reasons for merger/acquisition

The following reasons have been suggested as to why entities merge or acquire.

- Increased market share/power. In a market with limited product differentiation, price may be the main competitive weapon. In such a case, large market share may enable an entity to drive prices – for example reducing prices in the short term to eliminate competition before increasing prices later.

- Economies of scale. These result when expansion of the scale of productive capacity of an entity (or industry) causes total production costs to increase less than proportionately with output. It is clear that a merger which resulted in horizontal or vertical integration could give such economies since, at the very least, duplication would be avoided. But how could a conglomerate merger give economies? Possibly through central facilities such as offices, accounting departments and computer departments being rationalised. (Indeed, both sets of management are unlikely to be needed in their entirety.)

- Combining complementary needs. Many small entities have a unique product but lack the engineering and sales organisations necessary to produce and market it on a large scale. A natural course of action would be to merge with a larger entity. Both entities gain something – the small entity gets ‘instant’ engineering and marketing departments, and the large entity gains the revenue and other benefits which a unique product can bring. Also if, as is likely, the resources which each entity requires are complementary, the merger may well produce further opportunities that neither would see in isolation.

- Improving efficiency. A classic takeover target would be an entity operating in a potentially lucrative market but which, owing to poor management or inefficient operations, does not fully exploit its opportunities. Of course, being taken over would not be the only way of improving such a poor performer, but such an entity’s managers may be unwilling to give themselves the sack.

- A lack of profitable investment opportunities – surplus cash. An entity may be generating a substantial volume of cash, but sees few profitable investment opportunities. If it does not wish to simply pay out the surplus cash as dividends (because of its long-term dividend policy, perhaps), it could use it to acquire other entities.

A reason for doing so is that entities with excess cash are usually regarded as ideal targets for acquisition – a case of buy or be bought.

- Tax relief. An entity may be unable to claim tax relief because it does not generate sufficient profits. It may therefore wish to merge with another entity which does generate such profits.

- Reduced competition. It is often one benefit of merger activity – provided that it does not fall foul of the competition authorities.

- Asset-stripping. A predator acquires a target and sells the easily separable assets, perhaps closing down or disposing of some of its operations.

The following reasons are of questionable validity:

- Diversification, to reduce risk. While acquiring an entity in a different line of activity may diversify away risk for the entities involved, this is surely irrelevant to the shareholders. They could have performed exactly the same diversification simply by holding shares in both entities. The only real diversification produced is in the risk attaching to the managers’ and employees’ jobs, and this is likely to make them more complacent than before – to the detriment of shareholders’ future returns.

Shares of the target entity are undervalued. This may well be the case, although it would conflict with the efficient markets theory. However, the shareholders of the entity planning the takeover would derive as much benefit (at a lower administrative cost) from buying such undervalued shares themselves. This also assumes that the acquirer entity’s management are better at valuing shares than professional investors in the market place.

Advantages/disadvantages of organic growth and acquisition

Acquisition is often undertaken as an alternative to organic growth. It is important to understand the relative advantages and disadvantages of these two alternatives.

Advantages of organic growth (disadvantages of growth by acquisition)

- Organic growth allows planning of strategic growth in line with stated objectives.

- It is less risky than growth by acquisition – done over time.

- The cost is often much higher in an acquisition – significant acquisition premiums.

- Avoids problems integrating new acquired companies – the integration process is often a difficult process due to cultural differences between the two companies.

- An acquisition places an immediate pressure on current management resources to learn to manage the new business.

Advantages of growth by acquisition (disadvantages of organic growth)

- Quickest way is to enter a new product or geographical market.

- Reduces the risk of over-supply and excessive competition.

- Fewer competitors.

- Increase market power in order to be able to exercise some control over the price of the product, e.g. monopoly or by collusion with other producers.

- Acquiring the target company’s staff highly trained staff – may give a competitive edge.

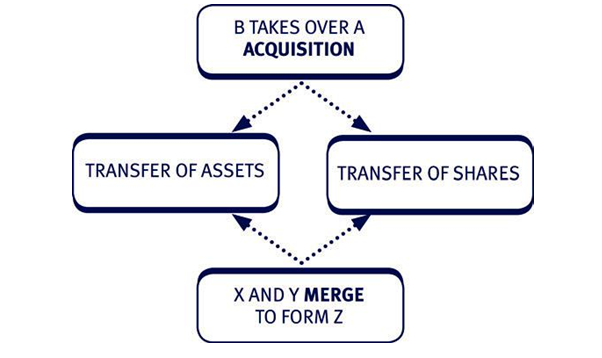

Corporate and competitive aspects of mergers Methods of mergers and acquisitions

Though the terms are used loosely to describe a variety of activities, in every case the end result is that two companies become a single enterprise, in fact if not in name, the end result is achieved by:

- transfer of assets

- transfer of shares.

The two methods of undertaking acquisitions and mergers are summarised as follows:

| Transfer of assets | Transfer of shares | |

| Acquisition | B acquires trade and | B acquires shares in A |

| (B takes over A) | assets from A for cash. | from A’s shareholders in |

| A is then liquidated, and | exchange for cash. A, as | |

| the proceeds received | a subsidiary of B, may | |

| by the old shareholders | subsequently transfer its | |

| of A. | trade and assets to its | |

| new parent company (B). | ||

| Merger (X and Y | Z acquires trade and | Z acquires shares in X |

| merge to form Z) | assets from both X and | and Y in return for its own |

| Y in return for shares in | shares. X and Y as | |

| Z. X and Y are then | subsidiaries of Z may | |

| liquidated and the | subsequently transfer | |

| shares in Z distributed | their trade and assets to | |

| in specie to the | their new parent | |

| shareholders of X | company (Z). | |

| and Y. |

Corporate issues arising on acquisition

Various corporate issues can arise on acquisition of one company by another:

- Impact on board structure – a power struggle among the directors will not help the post-acquisition integration of the two firms.

- Board hostility.

- Impact on corporate governance.

- Culture differences – this can be especially marked when the two companies are based in different countries.

- Loss of key personnel from target company.

- Integration difficulties – e.g. systems, operations.

- Adverse PR – especially if there is a threat of job losses as a consequence of the takeover.

Competitive issues

When considering acquisitions and mergers the competitive aspects need to be considered.

- One of the motives for acquiring a company is to remove competitive rivalry from the market.

For example, consolidation in the pharmaceuticals industry:

In 2014, Novartis AG and GlaxoSmithKline agreed a merger that reduced the number of competitors and as such the level of competition in this market.

They agreed to swap $20 billion in assets in what amounted to major restructurings for both firms.

Novartis bought GlaxoSmithKline’s cancer drug business, GSK took Novartis’s vaccine business, and the companies agreed to combine their respective over-the-counter and consumer drug businesses.

3 Identifying possible acquisition targets

When a company decides to expand by acquisition, its directors will produce criteria (size, location, finances, products, expertise, management) against which targets can be judged.

Directors and/or advisors then seek out prospective targets in the business sectors it is interested in.

The team then examines each prospect closely from both a commercial and financial viewpoint against the important criteria.

Steps in identifying acquisition targets

Steps to be taken

Assuming that external growth has been decided upon, the firm needs to consider the steps to be taken. A possible sequence of steps is as follows (given in the context of acquisitions, although much will apply to mergers as well):

- Strategic steps

– Step 1: Appraise possible acquisitions.

– Step 2: Select the best acquisition target.

– Step 3: Decide on the financial strategy, i.e. the amount and the structure of the consideration.

- Tactical steps

– Step 1: Launch a dawn raid subject to relevant regulation.

– Step 2: Make a public offer for the shares not held.

– Step 3: Success will be achieved if more than 50% of the target company’s shares are acquired.

Information required for the appraisal of acquisitions

The following needs to be considered when appraising a target for acquisition:

- Organisation

- Sales and marketing

- Production, supply and distribution

- Technology

- Accounting information

- Treasury information

- Tax information.

When considering a target for acquisition a company need to assess carefully the following – this information would only be available pre-acquisition where an agreed bid was negotiated.

| Organisation | (2) | Sales and marketing | ||||

| Special requirements, e.g. | Special requirements, e.g. | |||||

| organisation chart, key | | historic and future sales | ||||

| management and quality | volumes by product group | |||||

| employee analysis, terms | and geographical location | |||||

| and conditions | | market position, including | ||||

| unionisation and industrial | customers and competition | |||||

| for major product groups | ||||||

| relations | ||||||

| | normal trading terms | |||||

| pension arrangements. | ||||||

| | historic sales and promotions | |||||

| Clearly, businesses are about | ||||||

| expenditure by product | ||||||

| people, and their quality and | ||||||

| group. | ||||||

| organisation requires examination. | ||||||

| Further, comparison needs to be | This additional information should | |||||

| made with existing group | provide a detailed assessment of | |||||

| remuneration levels and pensions, | the market and customer base to | |||||

| to determine the financial impact | be acquired. | |||||

| of their adoption, where | ||||||

| appropriate, on the acquisition. | ||||||

| Production, supply and | (4) | Technology | ||||

| distribution | Special requirements, e.g. | |||||

| Special requirements, e.g. | ||||||

| | details of particular technical | |||||

| total capacity and current | skills inherent in the | |||||

| usage levels | acquisition | |||||

| need for future capital | | research and development | ||||

| investment to replace | organisation and historic | |||||

| existing assets, or meet | expenditure. | |||||

| expanded volume | Thus, an analysis would be made | |||||

| requirements. | ||||||

| of the technical assets acquired, | ||||||

| This would provide an assessment | and their past and potential future | |||||

| of the overhead burden due to | maintenance costs. | |||||

| under capacity production and of | ||||||

| the potential future capital | ||||||

| requirements to maintain the | ||||||

| required productive capacity of the | ||||||

| business. | ||||||

| Accounting information | (6) | Treasury information | |||

| Special requirements, e.g. | Special requirements, e.g. | ||||

| company searches for all | | amounts, terms and security | |||

| companies | of bank facilities and all other | ||||

| historic consolidated and | external loans and leasing | ||||

| facilities (including | |||||

| individual company accounts | |||||

| capitalised value, if not | |||||

| detailed explanation of | capitalised) | ||||

| accounting policies | | details of restrictive | |||

| explanation of major | covenants and trust deeds | ||||

| fluctuations in sales, gross | for such facilities | ||||

| margins, overheads and | | details of forward foreign | |||

| capital employed. | |||||

| exchange contracts, and | |||||

| These provide the background for | |||||

| exchange management | |||||

| basic financial analysis. | policies. | ||||

| All this information will be useful in | |||||

| planning the financial absorption | |||||

| of the business into the acquiring | |||||

| group, and will in particular reveal | |||||

| any ‘hidden assets’ (e.g. low | |||||

| coupon loans) and ‘hidden | |||||

| liabilities’ (guarantees liable to be | |||||

| called, or hedged foreign | |||||

| exchange positions). | |||||

| Tax information | (8) | Other commercial/financial | ||||

| Special requirements, e.g. | information | |||||

| Special requirements, e.g. | ||||||

| historic tax computations, | ||||||

| | ||||||

| agreed, submitted and | details of ordinary and | |||||

| unsubmitted by company | preference shareholders, | |||||

| significant disputes with | with amounts held by each | |||||

| class, and voting restrictions | ||||||

| revenue | ||||||

| if appropriate, together with | ||||||

| trading losses brought | share options held and partly | |||||

| forward | paid shares | |||||

| potential tax liabilities, | | contingent liabilities, | ||||

| including deferred tax and | including litigation, forward | |||||

| sales tax | purchase or sales contracts, | |||||

| understanding of tax position | including capital | |||||

| commitments and loss- | ||||||

| of vendors, especially with | ||||||

| making contracts not | ||||||

| respect to capital gains tax | ||||||

| otherwise provided for | ||||||

| liability as a result of sale. | ||||||

| | actuarial assessment of | |||||

| current pension funding, with | ||||||

| assumptions. | ||||||

| This can identify any potential tax | This relates primarily to a better | |||||

| assets (e.g. utilisable losses) and | understanding of the capital | |||||

| liabilities (e.g. likely payments of | structure and shareholdings to be | |||||

| tax not provided), and assist in | acquired, and any potential | |||||

| pricing and structuring the | financial liabilities overhanging the | |||||

| transaction having regard to the | acquired company, of which the | |||||

| vendor’s tax position. | most significant may well be under | |||||

| funded pension schemes. | ||||||

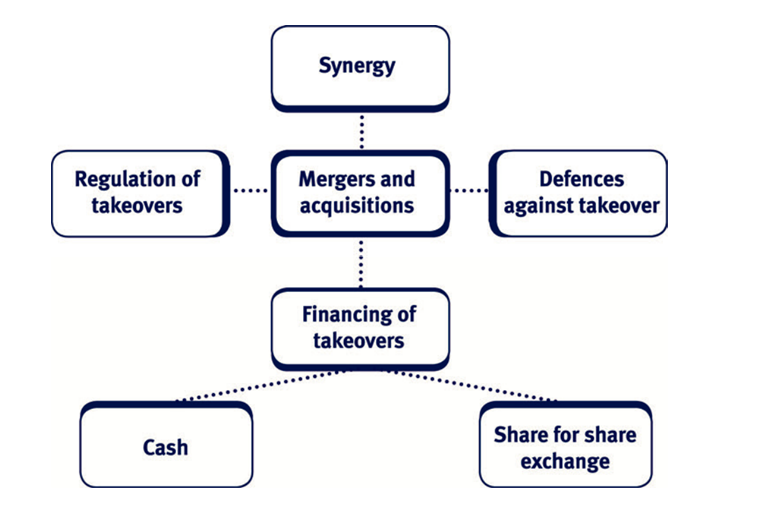

Synergy

Definition

Synergy may be defined as two or more entities coming together to produce a result not independently obtainable.

For example, a merged entity will only need one marketing department, so there may be savings generated compared to two separate entities.

Importance of synergy in mergers and acquisitions

For a successful business combination we should be looking for a situation where:

MV of combined company (AB) > MV of A + MV of B Note: MV means Market Value here.

If this situation occurs we have experienced synergy, where the whole is worth more than the sum of the parts. This is often expressed as 2 + 2 = 5.

It is important to note that synergy is not automatic. In an efficient stock market A and B will be correctly valued before the combination, and we need to ask how synergy will be achieved, i.e. why any increase in value should occur.

Sources of synergy

There are several reasons why synergistic gains arise. These break down into the following:

- revenue synergy, such as market power and combining complementary resources

- cost synergy, such as economies of scale

- financial synergy, such as elimination of inefficiency.

Types of synergy

Revenue synergy

Sources of revenue synergy include:

Market power/eliminate competition

Firms may merge to increase market power in order to be able to exercise some control over the price of the product. Horizontal mergers may enable the firm to obtain a degree of monopoly power, which could increase its profitability by pushing up the price of goods because customers have few alternatives.

Economies of vertical integration

Some acquisitions involve buying out other companies in the same production chain, e.g. a manufacturer buying out a raw material supplier or a retailer. This can increase profits by ‘cutting out the middle man’, improved control of raw materials needed for production, or by avoiding disputes with what were previously suppliers or customers.

Complementary resources

It is sometimes argued that by combining the strengths of two companies a synergistic result can be obtained. For example, combining a company specialising in research and development with a company strong in the marketing area could lead to gains.

Cost synergy

Sources of cost synergy are:

Economies of scale

Horizontal combinations (of companies in a similar line of business) are often claimed to reduce costs and therefore increase profits due to economies of scale. These can occur in the production, marketing or finance areas. Economies of scale occur through such factors as:

- fixed operating and administrative costs being spread over a larger production volume

- consolidation of manufacturing capacity on fewer and larger sites

- use of space capacity

- increased buyer power, i.e. bulk discounts

- savings on duplicated central services and accounting staff costs.

These benefits are sometimes also claimed for conglomerate combinations (of companies in unrelated areas of business) in financial and marketing costs.

Economies of scope

May occur in marketing as a result of joint advertising and common distribution.

Financial synergy

Sources of financial synergy include:

Elimination of inefficiency

If the ‘victim’ company in a takeover is badly managed its performance and hence its value can be improved by the elimination of inefficiencies. Improvements could be obtained in the areas of production, marketing and finance.

Elimination of inefficiency – Bargain buying

If the ‘victim’ company in a merger is badly managed its performance and hence its value can be improved by the elimination of inefficiencies.

Tax shields/accumulated tax losses

Another possible financial synergy exists when one company in an acquisition or merger is able to use tax shields or accumulated tax losses, which would have been unavailable to the other company.

Surplus cash

Companies with large amounts of surplus cash may see the acquisition of other companies as the only possible application for these funds. Of course, increased dividends could cure the problem of surplus cash, but this may be rejected for reasons of tax or dividend stability.

Corporate risk diversification

One of the primary reasons put forward for all mergers but especially conglomerate mergers is that the income of the combined entity will be less volatile (less risky) as its cash flows come from a wide variety of products and markets. This is a reduction in total risk, but has little or no effect on the systematic risk.

Diversification and financing

If the future cash flow streams of the two companies are not perfectly positively correlated then by combining the two companies the variability of their operating cash flow may be reduced. A more stable cash flow is more attractive to creditors and this could lead to cheaper financing.

Others

Other sources of synergy are:

Surplus managerial talent

Companies with highly skilled managers can make use of this resource only if they have problems to solve. The acquisition of inefficient companies is sometimes the only way of fully utilising skilled managers.

Speed

Acquisitions may be far faster than organic growth in obtaining a presence in a new and growing market.

The impact of mergers and acquisitions on stakeholders Impact on acquiring company’s shareholders

The existence of synergy has been discussed above as a key benefit to shareholders of an acquisition. All companies have a primary objective to maximise shareholder wealth, so it is clear that if synergy can be achieved, an acquisition should benefit the acquiring company’s shareholders.

Impact on the target company’s shareholders

The acquiring company will often pay a premium to the shareholders of the target company, to encourage them to sell their shares. Therefore there is also a financial benefit to them when a takeover happens.

Impact on lenders/debt holders

Debt will often be repayable in the event of a change in control. It all depends on whether the bank borrowings and bonds contain a change in control clause. With bank borrowings they almost certainly will. The risk profile of the acquirer may be quite different from that of the original borrower and the bank will not wish to become exposed to a higher credit risk. Bonds may be the same.

The acquirer is therefore likely to need to arrange new financing, debt and/or equity financing as appropriate in advance of the takeover.

Impact on managers and staff

In many acquisitions, an easy way to generate synergy is to make some staff redundant to avoid there being duplication of roles. Therefore, the managers and employees, particularly of the target company, often view a takeover with dread. However, the managers of the acquiring company often see takeovers as an opportunity, to demand higher salaries and bonuses now that they manage a larger company.

The acquirer may wish to retain many managers whose knowledge and skills may be essential to the successful continuation of the business, at least in the short term. In such a case, the acquirer may seek assurance and contractual tie-ins to ensure that such people remain with the business for a certain period of time.

Impact on society as a whole

Governments monitor takeovers carefully, and if they feel that a takeover will not be in the best interests of society as a whole, the takeover can be investigated and sometimes stopped. Competition law in most countries prevents monopolies being created which might be able to exploit their power to take advantage of customers.

Problems with acquisitions

If an acquisition generates the expected synergy, shareholders in both the acquiring company and the target should see an increase in wealth.

However, not all mergers and acquisitions are successful.

Synergy will not automatically arise. Unless the management of the two entities can work together effectively, there is a chance that any forecast benefits of the new arrangement might not be realised.

In many cases, the forecast synergy is not achieved, or is not as large as expected. It may be that the premium paid on acquisition by the acquirer was too high, so the shareholder value of the acquirer actually reduced as a result of the acquisition.

Also, cultural clashes between the two companies can make the integration of the two businesses very difficult.

Another reason for failure is that the opportunity cost of the investment could be too high. This means that the acquirer realises that the funds tied up in the acquisition could have been better used, to generate higher returns elsewhere.

Detailed reasons why mergers/acquisitions fail The fit/lack of fit syndrome

There may be a good fit of products or services, but a serious lack of fit in terms of management styles or corporate structure.

Lack of industrial or commercial fit

Failure can result from a horizontal or vertical takeover where the acquired entity turns out not to have the product range or industrial position that the acquirer anticipated. Usually in the case where a customer or supplier is acquired, the acquirer knows a lot about the acquired entity; even so, there may be aspects of the acquired entity’s operations which may cause unexpected problems for the acquirer, such that, even in these cases, a prospective acquisition should be planned very carefully and not be based solely on experience gained from a direct relationship with the acquired entity.

Lack of goal congruence

This may apply not only to the acquired entity but, more dangerously, to the acquirer, whereby disputes over the treatment of the acquired entity might well take away the benefits of an otherwise excellent acquisition.

‘Cheap’ purchases

The ‘turn around’ costs of an acquisition purchased at what seems to be a bargain price may well turn out to be a high multiple of that price. In these situations, the amount of resources in terms of cash and management time could well also damage the acquirer’s core business. In preparing a bid, a would-be acquirer should always take into account the likely total cost of an acquisition, including the input of its own resources, before deciding on making an offer or setting an offer price.

Paying too much

The fact that a high premium is paid for an acquisition does not necessarily mean that it will fail. Failure would result only if the price paid is beyond that which the acquirer considers acceptable to increase satisfactorily the long-term wealth of its shareholders.

Failure to integrate effectively

An acquirer needs to have a workable and clear plan of the extent to which the acquired company is to be integrated, and the amount of autonomy to be granted. At best, the plan should be negotiated with the acquired entity’s management and staff, but its essential requirements should be fairly but firmly carried out. The plan must address such problems as differences in management styles, incompatibilities in data information systems, and continued opposition to the acquisition by some of the acquired entity’s staff. Failure to plan can – and often does – lead to failure of an acquisition, as it leads to drift and demotivation, not only within the acquired entity but also within the acquirer itself.

Every aspect of a prospective acquisition, as it will affect the would-be acquirer, should be weighed up before embarking on a bid. Problems of integration have a much better chance of being resolved before bidding action is taken than they do after the event, when many more complications can ensue.

Even if a product fit is satisfactory, the would-be acquirer should be satisfied that the aspects of its own operation affected by the bid will be properly adaptable to the new activities. Running the rule carefully over one’s own operations may yield vital information as to areas which may need adaptation before a bid can be contemplated, and provide vital clues to appropriate areas for search when a bid has actually been launched. One factor of special importance is a clear assessment of the flexibility of one’s own information systems.

Inability to manage change

Several of the above points stress the need for an acquirer to plan effectively before and after an acquisition if failure is to be avoided. But this in itself calls for the ability to accept change – perhaps even radical change – from established routines and practices. Indeed, many acquisitions fail mainly because the acquirer is unable – or unwilling – reasonably to adjust its own activities to help ensure a smooth takeover. One such situation is where the acquired company has a demonstrably better data information system than the acquirer, which it might be greatly in the acquirer’s interest to adopt.

Defences against hostile takeover bids

Any listed company needs to be aware that a bid might be received at any time.

The directors of a company subject to a hostile takeover bid should act in the best interests of their shareholders. However, in practice they will also consider the views of other stakeholders (such as employees, and themselves).

If the board of directors of a target company decides to fight a bid that appears to be financially attractive to their shareholders, then they should consider one of the following defences:

- Pre-bid defences

– Communicate effectively with shareholders.

– Revalue non-current assets.

– Poison pill.

– Change the Articles of Association (super majority).

- Post-bid defences

– Appeal to their own shareholders.

– Attack the bidder.

– White Knight.

– Counterbid (‘Pacman’).

– Refer the bid to the Competition authorities.

Details of takeover defences

Pre-bid defences

Communicate effectively with shareholders

This includes having a public relations officer specialising in financial matters liaising constantly with the entity’s stockbrokers, keeping analysts fully informed, and speaking to journalists.

Revalue non-current assets

Non-current assets are revalued to current values to ensure that shareholders are aware of true asset value per share.

Poison pill strategy

Here a target company takes steps before a bid has been made to make itself less attractive to a potential bidder. The most common method is for existing shareholders to be given rights to buy future bonds or preference shares. If a bid is made before the date of exercise of the rights, then the rights will automatically be converted into full ordinary shares.

Super majority

The Articles of Association are altered to require that a higher percentage (say 80%) of shareholders have to vote for the takeover.

Post-bid defences

Appeal to their own shareholders

For example, by declaring that the value placed on the target company’s shares is too low in relation to the real value and earning power of the company’s assets, or alternatively that the market price of the bidder’s shares is unjustifiably high and is not sustainable.

A well-managed defensive campaign would include:

- Aggressive publicity on behalf of the company preferably before a bid is received. Investors may be told of any good research ideas within the company and of the management potential or merely be made more aware of the company’s achievements.

- Direct communication with the shareholders in writing stressing the financial and strategic reasons for remaining independent.

Note: Under the City Code in the UK, any forecasts must be examined and reported on by the auditors or consultant accountants.

Attack the bidder

Typically concentrating on the bidder’s management style, overall strategy, methods of increasing earnings per share, dubious accounting policies and lack of capital investment.

White Knight strategy

This is where the directors of the target company offer themselves to a more friendly outside interest. This tactic should only be adopted in the last resort as it means that the company will lose its independence. This tactic is acceptable provided that any information given to a preferred bidder is also given to a hostile bidder. The alternative company’s management will be considered to be sympathetic to the target company’s management.

Counterbid (Pacman defence)

Where the bidding company is itself the subject of a takeover bid by the target company.

Competition authorities

The target entity could seek government intervention by bringing in the Competition authorities. For this to be effective it would have to be proved that the takeover was against the public interest.

Test your understanding 2 – Development of bids

Follow the developments of bids in progress every day by reading a good financial newspaper. Can you see examples of where the above anti-takeover mechanisms have been used successfully?

Reverse takeovers

A reverse takeover is a type of acquisition/merger that is used by private companies that want to become public companies but want to avoid the high costs (time and money) that normally accompany stock market listings (initial public offerings, or IPOs).

How a reverse takeover works

First, the private company purchases a majority shareholding in a public company. Typically, the private company is larger than the public company.

Then, the private company’s shareholders exchange their private company shares for shares in the public company. Effectively, this turns the private company into a public company – its shares can now be publicly traded.

Advantages and disadvantages of reverse takeovers

Reverse takeovers allow a private company to become public without raising capital, which considerably simplifies the process. While conventional IPOs can take months to organise, reverse takeovers can be completed much more quickly, saving management time and money.

After the reverse takeover, the company’s shareholders should benefit from all the advantages of a stock market listing (e.g. shares are more marketable, the company’s profile is increased).

However, it is sometimes the case that the company’s managers are inexperienced in the additional regulatory and compliance requirements of being a public company. These burdens (and costs in terms of time and money) can prove significant.

Also, unless the company’s performance makes it attractive to stock market investors, there is no guarantee that simply being a public company will make its shares any more marketable.

Student Accountant article

The article ‘Reverse takeovers’ in the Technical Articles section of the

ACCA website provides further details on this topic.

6 The form of consideration for a takeover

Introduction

When one firm acquires another, two questions must be addressed regarding the form of consideration for the takeover:

- what form of consideration should be offered? Cash offer, or share exchange, or earnout are the three main choices.

- if a cash offer is to be made, how should the cash be raised? The choice is generally debt finance or a rights issue to generate the cash (if the entity does not have enough cash already).

The key considerations regarding these two questions are outlined below:

Form of consideration

Cash

In a cash offer, the target company shareholders are offered a fixed cash sum per share.

This method is likely to be suitable only for relatively small acquisitions, unless the bidding entity has an accumulation of cash.

Advantages:

- When the bidder has sufficient cash the takeover can be achieved quickly and at low cost.

- Target company shareholders have certainty about the bid’s value i.e. there is less risk compared to accepting shares in the bidding company.

- There is increased liquidity to target company shareholders, i.e. accepting cash in a takeover, is a good way of realising an investment.

- The acceptable consideration is likely to be less than with a share exchange, as there is less risk to target company shareholders. This reduces the overall cost of the bid to the bidding company.

Disadvantages:

- With larger acquisitions the bidder must often borrow in the capital markets or issue new shares in order to raise the cash. This may have an adverse effect on gearing, and also cost of capital due to the increased financial risk.

- For target company shareholders, in some jurisdictions a taxable chargeable gain will arise if shares are sold for cash, but the gain may not be immediately chargeable to tax under a share exchange.

- Target company shareholders may be unhappy with a cash offer, since they are ‘bought out’ and do not participate in the new group. Of course, this could be seen as an advantage of a cash offer by the bidding company shareholders if they want to keep full control of the bidding company.

Share exchange

In a share exchange, the bidding company issues some new shares and then exchanges them with the target company shareholders. The target company shareholders therefore end up with shares in the bidding company, and the target company’s shares all end up in the possession of the bidding company.

Large acquisitions almost always involve an exchange of shares, in whole or in part.

Advantages:

- The bidding company does not have to raise cash to make the payment.

- The bidding company can ‘boot strap’ earnings per share if it has a higher P/E ratio than the acquired entity.

- Shareholder capital is increased – and gearing similarly improved – as the shareholders of the acquired company become shareholders in the post-acquisition company.

- A share exchange can be used to finance very large acquisitions.

Disadvantages:

- The bidding company’s shareholders have to share future gains with the acquired entity, and the current shareholders will have a lower proportionate control and share in profits of the combined entity than before.

- Price risk – there is a risk that the market price of the bidding company’s shares will fall during the bidding process, which may result in the bid failing. For example, if a 1 for 2 share exchange is offered based on the fact that the bidding company’s shares are worth approximately double the value of the target company’s shares, the bid might fail if the value of the bidding company’s shares falls before the acceptance date.

Earn-out

Definition of an earn-out arrangement: A procedure whereby owners/ managers selling an entity receive a portion of their consideration linked to the financial performance of the business during a specified period after the sale. The arrangement gives a measure of security to the new owners, who pass some of the financial risk associated with the purchase of a new entity to the sellers.

The purchase consideration is sometimes structured so that there is an initial amount paid at the time of acquisition, and the balance deferred.

Some of the deferred balance will usually only become payable if the target entity achieves specified performance targets.

Key issues relating to forms of consideration Considerations of different stakeholders

In order to evaluate which form of consideration is appropriate in a particular case, it is important to assess the positions of both the target company’s shareholders, and the bidding company and its shareholders.

Position of the target company’s shareholders

The target company’s shareholders may want to retain an interest in the business, in which case a cash offer would not be welcomed. However, there is a greater certainty of value with a cash offer (share prices fluctuate, so in a share exchange the target company’s shareholders cannot be completely sure whether they are receiving an appropriate valuation for their shares).

Position of the bidding company and its shareholders

The bidding company will have to issue new shares if it is to undertake a share exchange. This may require the consent of shareholders in a general meeting. The shareholders may be concerned in a share exchange that their control of the bidding company will be diluted by the issue and exchange of shares.

Another key consideration is the impact of the takeover on the bidding company’s financial statements. An issue of new shares could reduce the level of earnings per share (a measure which is often used as a key performance measure by market analysts). However, if a cash offer is made, the raising of the necessary cash could have a significant impact on the gearing of the bidding company.

Methods of financing a cash offer

If the bidding company has a large cash surplus, it might be able to make a cash offer without raising any new finance.

However, in most cases, this will not be the case, so various financing options will have to be considered by the bidding company. The main two options are debt or a rights issue.

Debt

The bidding company could borrow the required cash from the bank, or issue bonds in the market.

The advantage of using debt in this situation is the low cost of servicing the debt. However, raising new debt finance will increase the bidding company’s gearing. This will increase the risk to the bidding company’s shareholders, so might not be acceptable to the shareholders.

Rights issue

If the bidding company shareholders do not want to suffer the increased risk which debt finance would bring, the alternative would be for the bidding company to offer a rights issue to its existing shareholders. In this case, the company’s gearing (measured using market values) is not affected, although its earnings per share will fall as new shares are issued.

From the shareholders’ point of view, the problem with this financing option is that it is the shareholders themselves who have to find the money to invest.

Evaluating a share for share exchange

One popular question is to comment on the likely acceptance of a share for share offer. The procedure is as follows:

- Value the predator company as an independent entity and hence calculate the value of a share in that company.

- Repeat the procedure for the victim company.

- Calculate the value of the combined company post-integration. This is calculated as:

Value of predator company as independent company X

Value of victim company as independent company X

Value of any synergy X

––––

Total value of combined company X

––––

Calculate the number of shares post-integration:

Number of shares originally in the predator company X

Number of shares issued to victim company X

––––

Total shares post-integration X

––––

- Calculate the value of a share in the combined company, and use this to assess the change in wealth of the shareholders after the takeover.

Illustration 1

Company A has 200m shares with a current market value of $4 per share. Company B has 90m shares with a current market value of $2 per share.

A makes an offer of 3 new shares for every 5 currently held in B. A has worked out that the present value of synergies will be $40m.

Required:

Calculate the expected value of a share in the combined company (assuming that the given share prices have not yet moved to anticipate the takeover), and advise the shareholders in company B whether the offer should be accepted.

Solution

MV of A = $800m

MV of B = $180m

PV of synergies = $40m

TOTAL = $1,020m

No. of new shares = 200m + (3/5) × 90m = 254m

New share price = 1,020m/254m = $4.02

| Shares | MV | Old wealth | Change | |

| A | 200m | $804m | $800m | $4m |

| B | (3/5) × 90m = 54m | $216m | $180m | $36m |

The wealth of the shareholders in company B will increase by $36m as a consequence of the takeover. This is a (36/180) 20% increase in wealth.

Company B’s shareholders should be advised to accept the 3 for 5 share for share offer.

Further numerical illustration

Initial example – Cash offer

Summary of information regarding Entity A and Entity B, two UK companies (currency £):

| Entity A | Entity B | |

| Market price per share (£) | 75 | 15 |

| Number of shares | 100,000 | 60,000 |

| Market value (£) | 7,500,000 | 900,000 |

Required:

If A intends to pay £1.2m cash for B, what is the cost premium if:

- the share price does not anticipate the takeover

- the share price of Entity B includes a ‘speculation’ element of £2 per share?

Solution

- The share price accurately reflects the true value of the entity (in theory).

Therefore, the cost to the bidder is simply £1,200,000 – £900,000, that is, £300,000.

Entity A is paying £300,000 for the identified benefits of the takeover.

- The cost is £300,000 + (60,000 × £2), or £420,000.

The entity is therefore really worth only £13 × 60,000, or £780,000.

Follow up example – Share exchange

Suppose A offers 16,000 shares (£1.2m/£75) instead of £1.2m cash. The cost appears to be £300,000 as before, but because B’s shareholders will own part of A, they will benefit from any future gains of the combined entity. Their share will be (16,000/(16,000 + 100,000)), or 13.8%.

Further, suppose that the benefits of the combination have been identified by A to have a present value of £400,000 (i.e. A thinks that B is really worth £900,000 + £ 400,000, or £1.3m). Therefore, the combined entity of A and B is worth £7.5m + £1.3m, or £8.8m.

Required:

Calculate the true cost of the takeover to the acquirer’s shareholders.

| Solution | ||

| Estimate of post-acquisition prices | A | B |

| Proportion of ownership | 86.2% | 13.8% |

| Market value: £8.8m × proportion | £7.586m | £1.214m |

| Number of shares currently in issue | 100,000 | 60,000 |

| Price per share (£) | 75.86 | 20.23 |

What we are attempting to do here is to value the shares in the entity before the takeover is completed, based on estimates of what the entity will be worth after the merger. The valuation of each entity also recognises the split of the expected benefits which will accrue to the combined form once the merger has taken place.

| The true cost to A can now be calculated as follows: | £ | ||

| 60,000 B shares at £20.23 | 1,213,800 | ||

| Less: Current market value | (900,000) | ||

| –––––––– | |||

| Benefits being paid to B’s shareholders | 313,800 | ||

| –––––––– | |||

The regulation of takeovers

Introduction to regulation

During a takeover, it is important that the companies comply with relevant legislation and regulations.

General principles of takeover regulation

The regulation of takeovers varies from country to country but focuses primarily on controlling the directors’ behaviour and ensuring that the shareholders are treated fairly.

General principles include the following:

- At the most important time in the company’s life – when it is subject to a takeover bid – its directors should act in the best interest of their shareholders, and should disregard their personal interests.

- All shareholders must be treated equally.

- Shareholders must be given all the relevant information to make an informed judgement.

- The board must not take action without the approval of shareholders, which could result in the offer being defeated.

- All information supplied to shareholders must be prepared to the highest with standards of care and accuracy.

- The assumptions on which profit forecasts are based and the accounting polices used should be examined and reported on by accountants.

- An independent valuer should support valuations of assets.

Examples of regulation

Although the exam questions will never test the details of any particular country’s regulations, it might be useful to see how the general principles listed above are applied in the UK. Similar examples could be given for other countries.

The City Code (or Takeover Code)

The acquisition of quoted companies in the UK is regulated by the City Code on Takeovers and Mergers (‘the City Code’), which is the responsibility of the Panel on Takeovers and Mergers.

This code does not have the force of law. It is enforced by the various City regulatory authorities, including the Stock Exchange (which has the power to suspend a company which does not comply), and specifically by the Panel on Takeovers and Mergers (the ‘Takeover Panel’).

Its basic principle is that of equity between one shareholder and another and it sets out rules for the conduct of acquisitions.

Competition and Markets Authority

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) replaced both the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) and the Competition Commission on 1 April 2014.

Many bids, because of their size, will require review by the CMA, and a limited number will subsequently be investigated if the CMA thinks that a merger might be against the public interest (i.e. constraining of competition).

As a rule of thumb the CMA may investigate an acquisition if it will result in the combined entity acquiring 25% or more of market share.

The investigations may take several months to complete during which time the merger is put on hold, thus giving the target company valuable time to organise its defence. The acquirer may abandon its bid as it may not wish to become involved in a time consuming investigation.

The CMA may simply accept or reject the proposals or accept them subject to certain conditions.

In recent years, the Competition Commission (former name of the CMA) has investigated the several UK banking mergers and also mergers in the UK airport industry. BAA was told by the Commission in 2009 that it had to sell off three of its existing airports in order to open up the market.

In addition, if the offer gives rises to a concentration (i.e. a potential monopoly) within the EU, the European Commission may initiate proceedings. This can result in considerable delay, and constitutes grounds for abandoning a bid.

Shareholder/stakeholder models of regulation

In the UK and US the market-based ‘shareholder model’ of regulation is used:

- Shareholder model – to protect rights of shareholders.

- Wide shareholder base.

In contrast, the European model looks at regulation from a wider stakeholder perspective:

- Stakeholder perspective to protect all stakeholders in a company.

- Stakeholders include:

– employees

– creditors

– government

– suppliers

– general public.

Which model is better?

There is a wide ranging debate as to whether the shareholder or stakeholder model is better from an economic and a more general public interest viewpoint.

- Stakeholder model appears to be more successful at dealing with the agency problem and managerial abuse of their power.

- Shareholder model appears to be more economically efficient.

- In practice the shareholder model is becoming more dominant:

– Due to strength of UK/US economies.

– Power of US/UK capital markets.

– The move is reflected in legislation.

- Synergy is often gained through redundancies in an acquired firm. Many are concerned with what they see as an unethical practice. A stakeholder model is more likely to give emphasis to employee protection.

Specific examples of takeover regulation

The principle of equal treatment

This stipulates that all shareholder groups must be offered the same terms, and that no shareholder group’s terms are more or less favourable than another group’s terms.

The main purpose of this principle is to ensure that minority shareholders are offered the same level of benefits, as the previous shareholders from whom the controlling stake in the target company was obtained.

Squeeze-out rights

Squeeze-out rights allow the bidder to force minority shareholders to sell their stakes, at a fair price, once the bidder has acquired a specific percentage of the target company’s equity. The percentage varies between countries but typically ranges between 80% and 95%.

The main purpose of this is to enable the acquirer to gain a 100% stake of the target company and prevent problems arising from minority shareholders at a later date.

The mandatory-bid condition through sell out rights

This allows remaining shareholders to exit the company at a fair price once the bidder has accumulated a certain number of shares. The amount of shares accumulated before the rule applies varies between countries. The bidder must offer the shares at the highest share price, as a minimum, which had been paid by the bidder previously.

The main purpose of this condition is to ensure that the acquirer does not exploit its position of power at the expense of minority shareholders.

Merger and acquisition accounting

- There are two different methods of consolidation designed to reflect the substance of two different types of business combination.

- Acquisition accounting is used for the purchase of one company by another with the purchaser controlling the net assets of the subsidiary.

– Net assets acquired are included at their fair values.

– Only post-acquisition profits of the subsidiary included in consolidated reserves.

- Merger accounting is when there is a pooling of interests of two or more roughly equal partners. Effectively adds the two sets of accounts together.

- The investment in a new subsidiary will be shown as a fixed asset investment in the parent company’s own accounts.

- The amount at which this investment will be stated will depend upon whether merger accounting or acquisition accounting is used.

- Under acquisition accounting the investment will be recorded at cost (generally the fair value of the consideration given).

- If merger accounting is used the investment is recorded at the nominal value of the shares issued as purchase consideration plus the fair value of any additional consideration.

Comparison of merger and acquisition accounting – Illustration

Fred makes an offer to all the shareholders of Ginger to acquire their shares on the basis of one new $1 share (market value $3) plus 25 c for every two $1 shares (market value $1.10 each) in Ginger. The holders of 95,000 shares in Ginger (representing 95% of the total shares) accept this offer.

The investment in Ginger will be recorded in the books of Fred as follows:

If acquisition accounting is to be used on consolidation:

| $ | $ | |

| Dr: Investment in Ginger plc | 154,375 | |

| Cr: $1 ordinary shares | 47,500 | |

| Cr: Share premium | 95,000 | |

| Cr: Cash | 11,875 | |

| ––––––– | ––––––– | |

| 154,375 | 154,375 | |

| ––––––– | ––––––– |

If merger accounting is to be used on consolidation:

$ $

Dr: Investment in Ginger plc 59,375

Cr: $1 ordinary shares 47,500

Cr: Cash 11,875

–––––– ––––––

59,375 59,375

–––––– ––––––