FULL COST-PLUS PRICING

In full cost-plus pricing the sales price is determined by calculating the full cost of the product and then adding a percentage mark-up for profit. The most important criticism of full cost-plus pricing is that it fails to recognise that since sales demand may be determined by the sales price, there will be a profit-maximising combination of price and demand.

Reasons for its popularity

In practice cost is one of the most important influences on price. Many firms base price on simple cost-plus rules (costs are estimated and then a mark-up is added in order to set the price). A study by Lanzilotti gave a number of reasons for the predominance of this method.

- Planning and use of scarce capital resources are easier.

- Assessment of divisional performance is easier.

- It emulates the practice of successful large companies.

- Organisations fear government action against ‘excessive’ profits.

- There is a tradition of production rather than of marketing in many organisations.

- There is sometimes tacit collusion in industry to avoid competition.

- Adequate profits for shareholders are already made, giving no incentive to maximise profits by seeking an ‘optimum’ selling price.

- Cost-based pricing strategies based on internal data are easier to administer.

- Over time, cost-based pricing produces stability of pricing, production and employment.

Full cost-plus pricing is a method of determining the sales price by calculating the full cost of the product and adding a percentage mark-up for profit.

Setting full-cost plus prices

The ‘full cost’ may be a fully absorbed production cost only, or it may include some absorbed administration, selling and distribution overhead.

A business might have an idea of the percentage profit margin it would like to earn, and so might decide on an average profit mark-up as a general guideline for pricing decisions. This would be particularly useful for businesses that carry out a large amount of contract work or jobbing work, for which individual job or contract prices must be quoted regularly to prospective customers. However, the percentage profit mark-up does not have to be rigid and fixed, but can be varied to suit the circumstances. In particular, the percentage mark-up can be varied to suit demand conditions in the market.

Problems with and advantages of full cost-plus pricing

There are several serious problems with relying on a full cost approach to pricing.

- It fails to recognise that since demand may be determining price, there will be a profit-maximising combination of price and demand.

- There may be a need to adjust prices to market and demand conditions.

- Budgeted output volume needs to be established. Output volume is a key factor in the overhead absorption rate.

- A suitable basis for overhead absorption must be selected, especially where a business produces more than one product.

However, it is a quick, simple and cheap method of pricing which can be delegated to junior managers (which is particularly important with jobbing work where many prices must be decided and quoted each day) and, since the size of the profit margin can be varied, a decision based on a price in excess of full cost should ensure that a company working at normal capacity will cover all of its fixed costs and make a profit.

Example: full cost-plus versus profit-maximising prices

Tiger has budgeted to make 50,000 units of its product, timm. The variable cost of a timm is RWF5,000 and annual fixed costs are expected to be RWF150,000,000.

The financial director of Tiger has suggested that a mark-up of 25% on full cost should be charged for every product sold. The marketing director has challenged the wisdom of this suggestion, and has produced the following estimates of sales demand for timms.

MARGINAL COST-PLUS PRICING OR MARK-UP PRICING

Marginal cost-plus pricing involves adding a profit margin to the marginal cost of production/sales. A marginal costing approach is more likely to help with identifying a profitmaximising price.

Whereas a full cost-plus approach to pricing draws attention to net profit and the net profit margin, a variable cost-plus approach to pricing draws attention to gross profit and the gross profit margin or contribution.

Marginal cost-plus pricing/mark-up pricing is a method of determining the sales price by adding a profit margin on to either marginal cost of production or marginal cost of sales.

The advantages and disadvantages of a marginal cost-plus approach to pricing

Here are the advantages.

- It is a simple and easy method to use.

- The mark-up percentage can be varied, and so mark-up pricing can be adjusted to reflect demand conditions.

- It draws management attention to contribution, and the effects of higher or lower sales volumes on profit. In this way, it helps to create a better awareness of the concepts and implications of marginal costing and cost-volume-profit analysis. For example, if a product costs RWF k10 per unit and a mark-up of 150% is added to reach a price of RWF k25 per unit, management should be clearly aware that every additional RWF k1 of sales revenue would add 600 francs to contribution and profit.

- In practice, mark-up pricing is used in businesses where there is a readilyidentifiable basic variable cost. Retail industries are the most obvious example, and it is quite common for the prices of goods in shops to be fixed by adding a mark-up (20% or 33.3%, say) to the purchase cost.

There are, of course, drawbacks to marginal cost-plus pricing.

- Although the size of the mark-up can be varied in accordance with demand conditions, it does not ensure that sufficient attention is paid to demand conditions, competitors’ prices and profit maximisation.

- It ignores fixed overheads in the pricing decision, but the sales price must be sufficiently high to ensure that a profit is made after covering fixed costs.

In our study of decision making to date we have adopted a marginal cost approach in that we have considered the effects on contribution and have classed (most) fixed overheads as irrelevant. In pricing decisions, however, there is a conflict with such an approach because of the need for full recovery of all costs incurred.

ECONOMISTS’ VERSUS ACCOUNTANTS’ VIEWS ON PRICING DECISIONS

Economic theory claims that profit is maximised by setting a price so that marginal cost equals marginal revenue. But because most cost accounting systems are set up to provide information for financial reporting purposes, it can be difficult to identify short-run or long-run marginal cost, even if ABC is used.

Mike Lucas (Management Accounting, June 1999) looked at this topic. What follows is a summary of his article.

Research by accountants has suggested that full costs play an important role in many pricing and output decisions. The use of full cost is at odds with the economists’ view that prices should be set at a level which equates marginal cost and marginal revenue, however.

Economic research findings

Economic research by Hall and Hitch in 1939 found that most organisations tended to set prices by adding a fairly constant mark-up to full cost for three principal reasons.

Organisations have no knowledge of their demand curves because of a lack of information about customers’ preferences and/or competitor reaction to price changes. b) Price stickiness

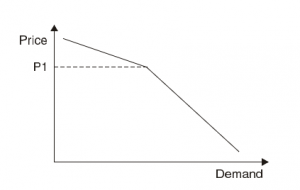

As illustrated in the diagram below (a kinked demand curve), an organisation may feel that if prices are increased above the current price P1, competitors will not match the increase, demand being very elastic. The increase in profit per unit will not compensate for the profit lost from the reduction in quantity sold, and so total profit will fall.

If price is reduced below the current price P1, competitors will match the price decrease, demand being inelastic. The small increase in the quantity sold will not compensate for the drop in profit per unit, and so total profit will fall.

The organisation would therefore be reluctant to increase or decrease the price from the current level if there are minor changes in costs or market conditions, giving rise to apparent price stickiness.

) The frequent price changes which are likely to occur if profit-maximising prices are set (as prices are changed whenever there is a change in demand or costs) can be administratively expensive to bring in and can inconvenience sales staff, distributors as well as customers.

Economists countered the suggested predominance of cost-based approaches, however, with arguments of ‘implicit marginalism’, whereby organisations act as though they are setting prices on the basis of equating MC and MR, even if this approach is not consciously adopted. Evidence for this includes:

- Discounting prices when market circumstances change and/or accepting a lower profit margin when competition increases. This is similar to using a marginal revenue function.

- Reducing the overhead charged to products to reflect the short-term nature of some fixed costs. This is similar to using a marginal cost function.

Reconciling full cost pricing and marginalist, profit-maximising principles

Some economists have tried to show that full cost pricing is compatible with marginalist principles. One argument (by Koutsoylannis) is that: Price (P) = average variable cost (AVC) + costing margin where the costing margin = average fixed cost (AFC) + normal profit mark-up.

Taking AVC to be the best available approximation of long-run marginal cost, any adjustments made to the costing margin because of competitive forces can be viewed as the organisation attempting to establish its demand curve, and so – by implication – its marginal revenue function.

Accounting research

Problems with the methods used for accounting research may not have picked up on the fact that organisations are constantly making adjustments to prices in order to meet market situations, and, while many organisations might believe they set prices on a cost plus basis, these prices are the actual prices charged in just a few situations.

ABC and long-run marginal cost

As you will know from your Certificate level studies, ABC costs should be long-run avoidable (marginal) costs and so in theory organisations using ABC costs are following economists’ views of pricing. The treatment of ‘indivisibilities’ means that this is not necessarily the case, however.

‘Indivisibilities’ occur when a reduction in the level of activity does not lead to a proportionate reduction in resource inputs. For example, a process may be duplicated so that output can be doubled but it may not necessarily be possible to halve the process if demand drops by 50%.

The cost of indivisible resources should therefore not be attributed to individual products as, to the extent that they are indivisible, they will be incurred regardless of the activity level and so are unavoidable in relation to a particular product.

Conclusion

Economic theory claims that profit is maximised by setting a price so that marginal cost equals marginal revenue. But because most cost accounting systems are set up to provide information for financial reporting purposes, it can be difficult to identify short-run or long-run marginal cost, even if ABC is used.

It is difficult to know whether organisations are carrying out the analysis necessary to determine marginal cost or whether the full cost provided by the accounting system is used for pricing decisions.

The debate over the theory of pricing therefore continues.

PRICING BASED ON MARK-UP PER UNIT OF LIMITING FACTOR

Another approach to pricing might be taken when a business is working at full capacity, and is restricted by a shortage of resources from expanding its output further. By deciding what target profit it would like to earn, it could establish a mark-up per unit of limiting factor.

Example: mark-up per unit of limiting factor

Suppose that a company provides a window cleaning service to offices and factories. Business is brisk, but the company is restricted from expanding its activities further by a shortage of window cleaners. The workforce consists of 12 window cleaners, each of whom works a 40 hour week. They are paid RWF400 per hour. Variable expenses are RWF600 per hour. Fixed costs are RWF1,500,000 per week. The company wishes to make a contribution of at least RWF5,000 per hour.

The minimum charge per hour for window cleaning would then be as follows.

| RWF per hour | |

| Direct wages | 400 |

| Variable expenses | 600 |

| Contribution | 5,000 |

| Charge per hour | 6,000 |

The company has a total workforce capacity of (12 × 40) 480 hours per week, and so total revenue would be RWF2,880,000 per week, contribution would be (480 × RWF5,000) RWF2,400,000, leaving a profit after fixed costs of RWF900,000per week.

BLANK

PRICING STRATEGIES FOR SPECIAL ORDERS

The basic approach to pricing special orders is minimum pricing.

What is a special order?

A special order is a one-off revenue-earning opportunity. These may arise in the following situations.

- When a business has a regular source of income but also has some spare capacity allowing it to take on extra work if demanded. For example a brewery might have a capacity of 500,000 barrels per month but only be producing and selling 300,000 barrels per month. It could therefore consider special orders to use up some of its spare capacity.

- When a business has no regular source of income and relies exclusively on its ability to respond to demand. A building firm is a typical example as are many types of subcontractors. In the service sector consultants often work on this basis.

The reason for making the distinction is that in the case of (a), a firm would normally attempt to cover its longer-term running costs in its prices for its regular product. Pricing for special orders need therefore take no account of unavoidable fixed costs. This is clearly not the case for a firm in (b)’s position, where special orders are the only source of income for the foreseeable future.

Minimum pricing

The minimum price is the price at which the organisation would break even if it undertook the work. It would have to cover the incremental costs of producing and selling the item and the opportunity costs of the resources consumed.

Firms with high overheads are faced with difficulties. Ideally some means should be found of identifying the causes of such costs. Activity based analysis might reveal ways of attributing overheads to specific jobs or perhaps of avoiding them altogether.

In today’s competitive markets it is very much the modern trend to tailor products or services to customer demand rather than producing for stock. This suggests that ‘special’ orders may become the norm for most businesses.

In the motor trade in the UK, an order for a new car is often fulfilled not from stock, but by programming that order into the manufacturing schedule. Each customer wants a different colour, trim and other accessories and it is cheaper to make to order than to make for stock in case a passing motorist wants just that car.

The same can be for furniture suites where many different combinations of colour/pattern and materials are available.

PRICING STRATEGIES FOR NEW PRODUCTS

Two pricing strategies for new products are market penetration pricing and market skimming pricing.

First on the market?

A new product pricing strategy will depend largely on whether a company’s product or service is the first of its kind on the market.

- If the product is the first of its kind, there will be no competition – yet and the company, for a time at least, will be a monopolist. Monopolists have more influence over price and are able to set a price at which they think they can maximise their profits. A monopolist’s price is likely to be higher, and its profits bigger, than those of a company operating in a competitive market.

- If the new product being launched by a company is following a competitor’s product onto the market, the pricing strategy will be constrained by what the competitor is already doing. The new product could be given a higher price if its quality is better, or it could be given a price which matches the competition. Undercutting the competitor’s price might result in a price war and a fall of the general price level in the market.

Market penetration pricing

Market penetration pricing is a policy of low prices when the product is first launched in order to obtain sufficient penetration into the market.

Circumstances in which a penetration policy may be appropriate

- If the firm wishes to discourage new entrants into the market

- If the firm wishes to shorten the initial period of the product’s life cycle in order to enter the growth and maturity stages as quickly as possible

- If there are significant economies of scale to be achieved from a high volume of output, so that quick penetration into the market is desirable in order to gain unit cost reductions

- If demand is highly elastic and so would respond well to low prices.

Penetration prices are prices which aim to secure a substantial share in a substantial total market. A firm might therefore deliberately build excess production capacity and set its prices very low. As demand builds up the spare capacity will be used up gradually and unit costs will fall; the firm might even reduce prices further as unit costs fall. In this way, early losses will enable the firm to dominate the market and have the lowest costs.

Market skimming pricing

Market skimming pricing involves charging high prices when a product is first launched and spending heavily on advertising and sales promotion to obtain sales.

As the product moves into the later stages of its life cycle, progressively lower prices will be charged and so the profitable ‘cream’ is skimmed off in stages until sales can only be sustained at lower prices.

The aim of market skimming is to gain high unit profits early in the product’s life. High unit prices make it more likely that competitors will enter the market than if lower prices were to be charged.

Circumstances in which such a policy may be appropriate

- Where the product is new and different, so that customers are prepared to pay high prices so as to be one up on other people who do not own it – e.g. the iPad.

- Where the strength of demand and the sensitivity of demand to price are unknown. It is better from the point of view of marketing to start by charging high prices and then reduce them if the demand for the product turns out to be price elastic than to start by charging low prices and then attempt to raise them substantially if demand appears to be insensitive to higher prices.

- Where high prices in the early stages of a product’s life might generate high initial cash flows. A firm with liquidity problems may prefer market-skimming for this reason.

- Where the firm can identify different market segments for the product, each prepared to pay progressively lower prices. If product differentiation can be introduced, it may be possible to continue to sell at higher prices to some market segments when lower prices are charged in others. This is discussed further below.

- Where products may have a short life cycle, and so need to recover their development costs and make a profit relatively quickly.

OTHER PRICING STRATEGIES

Product differentiation may be used to make products appear to be different. Price discrimination is then possible.

Product differentiation and price discrimination

Price discrimination is the practice of charging different prices for the same product to different groups of buyers when these prices are not reflective of cost differences.

In certain circumstances the same product can be sold at different prices to different customers. There are a number of bases on which such discriminating prices can be set.

| Basis | Detail |

| By market segment | A cross-border bus company could market its services at different prices in Rwanda and Uganda for say a return journey between Kampala and Kigali. |

| By product version | Many car models have optional extras which enable one brand to appeal to a wider cross-section of customers. The final price need not reflect the cost price of the optional extras directly: usually the top of the range model would carry a price much in excess of the cost of providing the extras – as a prestige appeal. |

| By place | Theatre seats are usually sold according to their location in the theatre so that patrons pay different prices for the same performance according to the seat type they occupy. |

| By time | This is perhaps the most popular type of price discrimination. Offpeak travel bargains, hotel prices and telephone charges are all attempts to increase sales revenue by covering variable but not necessarily average cost of provision. In Europe railway companies are successful price discriminators, charging more to rush hour rail commuters whose demand is inelastic at certain times of the day. |

Price discrimination can only be effective if a number of conditions hold.

- The market must be segmentable in price terms, and different sectors must show different intensities of demand. Each of the sectors must be identifiable, distinct and separate from the others, and be accessible to the firm’s marketing communications.

- There must be little or no chance of a black market developing (this would allow those in the lower priced segment to resell to those in the higher priced segment).

- There must be little or no chance that competitors can and will undercut the firm’s prices in the higher priced (and/or most profitable) market segments.

- The cost of segmenting and administering the arrangements should not exceed the extra revenue derived from the price discrimination strategy.

‘Own label’ pricing: a form of price discrimination

Many supermarkets and multiple retail stores sell their ‘own label’ products, often at a lower price than established branded products. The supermarkets or multiple retailers do this by entering into arrangements with manufacturers, to supply their goods under the ‘own brand’ label.

Premium pricing

This involves making a product appear ‘different’ through product differentiation so as to justify a premium price. The product may be different in terms of, for example, quality, reliability, durability, after sales service or extended warranties. Heavy advertising can establish brand loyalty which can help to sustain a premium and premium prices will always be paid by those customers who blindly equate high price with high quality.

Product bundling

Product bundling is a variation on price discrimination which involves selling a number of products or services as a package at a price lower than the aggregate of their individual prices. For example a hotel might offer a package that includes the room, meals, use of leisure facilities and entertainment at a combined price that is lower than the total price of the individual components. This might encourage customers to buy services that they might otherwise not have purchased and so increase cash-flow and contribution to fixed overheads.

The success of a bundling strategy depends on the expected increase in sales volume and changes in margin. Other cost changes, such as in product handling, packaging and invoicing costs, are possible. Longer-term issues such as competitors’ reactions must also be considered.

Another bundle could be a PC with software, printer and extended warranty insurance.

Pricing with optional extras

The decision here is very similar to that for product bundling. It rests on whether the increase in sales revenue from the increased price that can be charged is greater than the increase in costs required to incorporate extra features. Not all customers will be willing to pay a higher price for additional features if they do not want or need those features.

Psychological pricing

Psychological pricing strategies include pricing a product at RWF19,990 instead of RWF20,000 and withdrawing an unsuccessful product from the market and then relaunching it at a higher price, the customer having equated the lower price with lower quality (which was not the seller’s intention).

Multiple products and loss leaders

Most organisations sell a range of products. The management of the pricing function is likely to focus on the profit from the whole range rather than the profit on each single product. Take, for example, the use of loss leaders: a very low price for one product is intended to make consumers buy additional products in the range which carry higher profit margins.

Case Study

Printers for PCs – The printers are priced very attractive and low prices, but the ink cartridges are comparatively highly priced. Once you have bought the printer, the market for the ink cartridges is almost secure.

Using discounts

Reasons for using discounts to adjust prices

− To get rid of perishable goods that have reached the end of their shelf life

− To sell off seconds – cheaper than disposal and does help towards contribution

− Normal practice (e.g.2nd hand and antiques trade)

− To increase sales volumes during a poor sales period without dropping prices permanently

− To differentiate between types of customer (wholesale, retail and so on) − To get cash in quickly

Controlled prices

State owned or nationalised industries operate in a monopolistic environment. Their prices are regulated by the government or by a designated ministry. Over the next few years it is expected that shares in some will be offered to the public and they then will operate within the private sector. However they will probably be overseen by an industry regulator.

Regulators tend to concentrate on price so that these near monopolies cannot exploit their position (although the regulators are also concerned with quality of service/product and capital investment).

If a price is regulated, the elasticity of demand is zero: ‘small’ customers pay less than they otherwise would, whereas ‘large’ customers pay more than in a competitive environment.

In general though, prices have become more flexible in recent year through:

- Introduction of discounted prices for very large customers

- Entry of other companies into the market

If asked to compare two pricing strategies and to determine which is the better, you basically need to consider which produces the higher cash inflows.

When asked to assess the financial viability of the better strategy, however, you need to perform a DCF appraisal on the forecast cash flows.

CHAPTER ROUNDUP

- In full cost-plus pricing the sales price is determined by calculating the full cost of the product and then adding a percentage mark-up for profit. The most important criticism of full cost-plus pricing is that it fails to recognise, that since sales demand may be determined by the sales price, there will be a profit-maximising combination of price and demand.

- Marginal cost-plus pricing involves adding a profit margin to the marginal cost of production/sales. A marginal costing approach is more likely to help with identifying a profit-maximising price.

- Economic theory claims that profit is maximised by setting a price so that marginal cost equals marginal revenue. But, because most cost accounting systems are set up to provide information for financial reporting purposes, it can be difficult to identify short-run or long-run marginal cost, even if ABC is used.

- Another approach to pricing might be taken when a business is working at full capacity, and is restricted by a shortage of resources from expanding its output further. By deciding what target profit it would like to earn, it could establish a mark-up per unit of limiting factor.

- The basic approach to pricing special orders is minimum pricing.

- Two pricing strategies for new products are market penetration pricing and market skimming pricing.

- Product differentiation may be used to make products appear to be different. Price discrimination is then possible.