INTRODUCTION

The management, creditors, investors and others use the information contained in the statements of changes in financial position (funds and cash flow statements) to form judgment about the operating performance and financial position of the firm. Users of financial statements can get further insight about financial strengths and weaknesses of the firm if they properly analyse information reported in these statements. Management should be particularly interested in knowing financial strengths of the firm to make their best use and to be able to spot out financial weaknesses of the firm to take suitable corrective actions. The future plans of the firm should be laid down in view of the firm’s financial strengths and weaknesses. Thus, financial analysis is the starting point for making plans, before using any sophisticated forecasting and planning procedures.

Understanding the past is a prerequisite for anticipating the future.

USERS OF FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

Financial analysis is the process of identifying the financial strengths and weaknesses of the firm by properly establishing relationships between the items of the balance sheet and the profit and loss account. Financial analysis can be undertaken by the management of the firm, or by parties outside the firm, viz., owners, creditors, investors and others.1 The nature of analysis will differ depending on the purpose of the analyst.

- Trade creditors are interested in a firm’s ability to meet their claims over a very short period of time. Their analysis will, therefore, confine to the evaluation of the firm’s liquidity position.

- Suppliers of long-term debt, on the other hand, are concerned with the firm’s longterm solvency and survival. They analyze the firm’s profitability over time, its ability to generate cash to be able to pay interest and repay principal, and the relationship between various sources of funds (capital structure relationships). Long-term creditors do analyze the historical financial statements, but they place more emphasis on the firm’s projected, or pro forma, financial statements to make analysis about its future solvency and profitability.

- Investors, who have invested their money in the firm’s shares, are most concerned about the firm’s earnings. They restore more confidence in those firms that show steady growth in earnings. As such, they concentrate on the analysis of the firm’s present and future profitability. They are also interested in the firm’s financial structure to the extent it influences the firm’s earnings ability and risk.

- Management of the firm would be interested in every aspect of the financial analysis. It is their overall responsibility to see that the resources of the firm are used most effectively and efficiently, and that the firm’s financial condition is sound.

| Check Your Concepts 1. What is meant by financial analysis? 2. Who uses financial analysis and for what? |

NATURE OF RATIO ANALYSIS

Ratio analysis is a powerful tool of financial analysis. A ratio is defined as “the indicated quotient of two mathematical expressions” and as “the relationship between two or more things.”2 In financial analysis, a ratio is used as a benchmark for evaluating the financial position and performance of a firm. The absolute accounting figures reported in the financial statements do not provide a meaningful understanding of the performance and financial position of a firm. An accounting figure conveys meaning when it is related to some other relevant information. For example, a `5 crore net profit may look impressive, but the firm’s performance can be said to be good or bad only when the net profit figure is related to the firm’s investment. The relationship between two accounting figures, expressed mathematically, is known as a financial ratio (or simply as a ratio). Ratios help to summarize large quantities of financial data and to make qualitative judgment about the firm’s financial performance. For example, consider current ratio (discussed in detail later on). It is calculated by dividing current assets by current liabilities; the ratio indicates a relationship—a quantified relationship between current assets and current liabilities. This relationship is an index or yardstick, which permits a qualitative judgment to be formed about the firm’s ability to meet its current obligations. It measures the firm’s liquidity. The greater the ratio, the greater is the firm’s liquidity and vice versa. The point to note is that a ratio reflecting a quantitative relationship helps to form a qualitative judgment. Such is the nature of all financial ratios.

Standards of Comparison

The ratio analysis involves comparison for a useful interpretation of the financial statements. A single ratio in itself does not indicate favourable or unfavourable condition. It should be compared with some standard. Standards of comparison may consist of:3

- past ratios, i.e., ratios calculated from the past financial statements of the same firm;

- competitors’ ratios, i.e., ratios of some selected firms, especially the most progressive and successful competitor, at the same point in time;

- industry ratios, i.e., ratios of the industry to which the firm belongs; and

- projected ratios, i.e., ratios developed using the projected, or pro forma, financial statements of the same firm.

Time series analysis The easiest way to evaluate the performance of a firm is to compare its present ratios with the past ratios. When financial ratios over a period of time are compared, it is known as the time series analysis. It gives an indication of the direction of change and reflects whether the firm’s financial performance has improved, deteriorated or remained constant over time. The analyst should not simply determine the change, but, more importantly, he/she should understand why ratios have changed. The change, for example, may be affected by changes in the accounting policies without a material change in the firm’s performance.

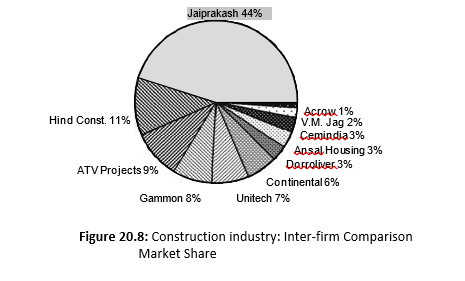

Cross-sectional analysis Another way of comparison is to compare ratios of one firm with some selected firms in the same industry at the same point in time. This kind of comparison is known as the cross-sectional analysis or inter-firm analysis. In most cases, it is more useful to compare the firm’s ratios with ratios of a few carefully selected competitors, who have similar operations. This kind of a comparison indicates the relative financial position and performance of the firm. A firm can easily resort to such a comparison, as it is not difficult to get the published financial statements of the similar firms.

Industry analysis To determine the financial condition and performance of a firm, its ratios may be compared with average ratios of the industry of which the firm is a member. This sort of analysis, known as the industry analysis, helps to ascertain the financial standing and capability of the firm vis-à-vis other firms in the industry. Industry ratios are important standards in view of the fact that each industry has its characteristics, which influence the operating relationships. But there are certain practical difficulties in using the industry ratios. First, it is difficult to get average ratios for the industry. Second, even if industry ratios are available, they are averages—averages of the ratios of strong and weak firms. Sometimes differences may be so wide that the average may be of little utility. Third, averages will be meaningless and the comparison futile if firms within the same industry widely differ in their accounting policies and practices. If it is possible to standardize the accounting data for companies in the industry and eliminate extremely strong and extremely weak firms, the industry ratios will prove to be very useful in evaluating the relative financial condition and performance of a firm.

Pro forma analysis Sometimes future ratios are used as the standard of comparison. Future ratios can be developed from the projected, or pro forma financial statements. The comparison of current or past ratios with future ratios shows the firm’s relative strengths and weaknesses in the past and the future. If the future ratios indicate weak financial position, corrective actions should be initiated.

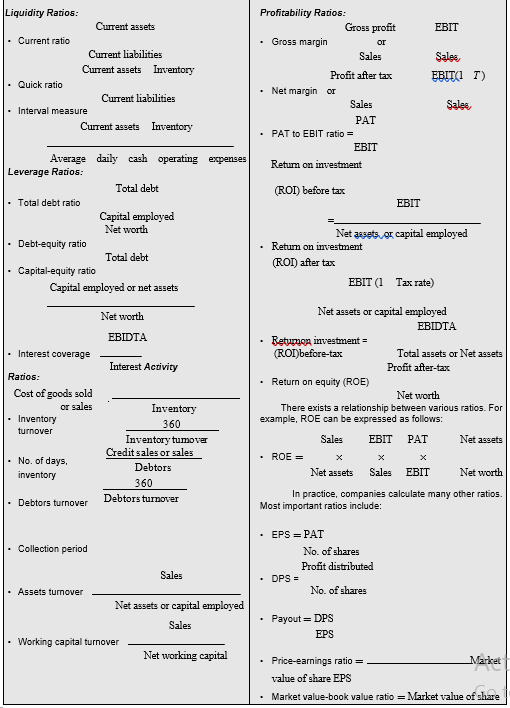

Types of Ratios

Several ratios, calculated from the accounting data, can be grouped into various classes according to the financial activity or function to be evaluated. As stated earlier, the parties interested in financial analysis are short- and long-term creditors, owners and management. Short-term creditors’ main interest is in the liquidity position or the short-term solvency of the firm. Long-term creditors, on the other hand, are more interested in the long-term solvency and profitability of the firm. Similarly, owners concentrate on the firm’s profitability and financial condition. Management is interested in evaluating every aspect of the firm’s performance. They have to protect the interests of all parties and see that the firm grows profitably. In view of the requirements of the various users of ratios, we may classify them into the following four important categories:4

- Liquidity ratios

- Leverage ratios

- Activity ratios

- Profitability ratios

Liquidity ratios measure the firm’s ability to meet current obligations, leverage ratios show the proportions of debt and equity in financing the firm’s assets, activity ratios reflect the firm’s efficiency in utilizing its assets and profitability ratios measure overall performance and effectiveness of the firm. Each of these ratios is discussed below. The accounting data are taken from the financial statements for the Hindustan Manufacturing Company (the real name of the company has been disguised) to illustrate calculation and use of ratios.

| Check Your Concepts

1. What is meant by financial ratio? 2. What are the types of ratios most commonly used in financial analysis? What does each type of theratios measure? 3. With reference to ratio analysis, explain the following: (a) time series analysis, (b) cross-section analysis, (c) industry analysis, (d) pro forma analysis. |

ILLUSTRATION 20.1: Assessing Financial Health of a Firm with Ratio Analysis

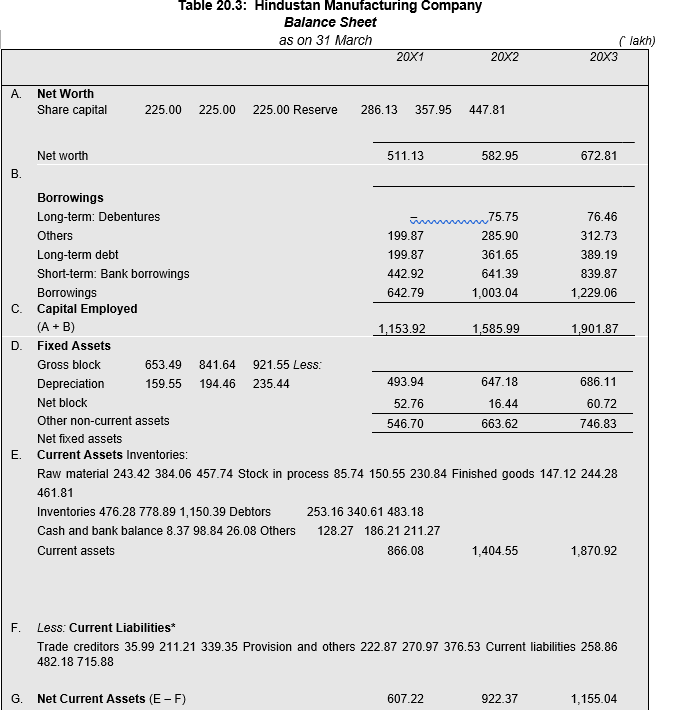

The Hindustan Manufacturing Company is a leading producer and exporter of engineering items such as steel pipes, ingots, billets, etc. It has also recently added a chemical plant and a paper plant as part of its diversification strategy. The company started with a share capital of `25 lakh in the early sixties, which has now increased to `225 lakh. The number of shares outstanding is 22.50 lakh. The average market price (AMP) of the company’s share during 20X1–20X3 has been: `26.38 in 20X1, `34.50 in 20X2 and `29.25 in 20X3. The financial data for the company are given in Tables 20.1 to 20.3. For illustrative purpose, calculations of ratios have been shown only for the year 20X3. However, tables indicating trend in ratios during 20X1–20X3 are also given.

Table 20.1: Hindustan Manufacturing Company

Profit and Loss Account

for the year ending on 31 March (` lakh)

| 20X1 | 20X2 | 20X3 | ||

| A. | Net sales* | 2,338.90 | 2,825.69 | 3,717.23 |

| B. | Cost of goods sold** | 1,929.04 | 2,322.80 | 3,053.66 |

| C. | Gross profit (A – B) | 409.86 | 502.89 | 663.57 |

| D. | Less: Selling and adm. expenses | 239.72 | 262.10 | 357.87 |

| E. | Operating income

(C – D) |

170.14 | 240.79 | 305.70 |

| F. | Add: Other income | 15.24 | 25.38 | 36.91 |

| G. | Earning before int.

and tax (EBIT) (E + F) |

185.38 | 266.17 | 342.61 |

| H. | Less: Interest | 59.84 | 124.98 | 143.46 |

| I. | Profit before tax (PBT) (G – H) | 125.54 | 141.19 | 199.15 |

| J. | Provision for tax | 41.79 | 30.00 | 64.29 |

| K. | Profit after tax (PAT) (I – J) | 83.75 | 111.19 | 134.86 |

| L. | Effective tax rate*** | 33% | 21% | 32% |

| M. | Dividend distributed | 33.75 | 39.38 | 45.00 |

| N. | Retained earnings | 50.00 | 71.81 | 89.86 |

* Net of excise duty.

** Depreciation included.

*** Provision for tax divided by profit before tax.

Table 20.2: Hindustan Manufacturing Company Statement of Cost of Goods Sold

for the year ending on March 31 (` lakh)

| 20X1 20X2 20X3 | |

| Raw material | 1,587.34 2,019.54 2,751.52 |

| Direct labour | 138.13 170.86 228.94 |

| Depreciation | 23.07 38.64 41.59 |

| Other mfg. expenses | 205.34 255.72 329.44

1,953.88 2,484.76 3,351.49 |

| Add: Opening stock in

process |

57.09 85.74 150.55

2,010.97 2,570.50 3,502.04 |

| Less: Closing stock in

process |

85.74 150.55 230.83 |

| Cost of Production | 1,925.23 2,419.95 3,271.21 |

| Add: Opening finished

stock |

150.93 147.12 244.26

2,076.16 2,567.07 3,515.47 |

| Less: Closing finished stock | 147.12 244.26 461.81 |

| Cost of Goods Sold | 1,929.04 2,322.81 3,053.66 |

| H. | Net Assets (D + G) 1,153.92 1,585.99 1,901.87 |

* If bank borrowings are considered, then the current liabilities for 20X1 through 20X3 will be: `701.78 lakh; `1123.57 lakh, and `1555.75 lakh.

LIQUIDITY RATIOS

It is extremely essential for a firm to be able to meet its obligations as they become due. Liquidity ratios measure the ability of the firm to meet its current obligations (liabilities). In fact, analysis of liquidity needs the preparation of cash budgets and cash and fund flow statements; but liquidity ratios, by establishing a relationship between cash and other current assets to current obligations, provide a quick measure of liquidity. A firm should ensure that it does not suffer from lack of liquidity, and also that it does not have excess liquidity. The failure of a company to meet its obligations due to lack of sufficient liquidity will result in a poor credit worthiness, loss of creditors’ confidence or even in legal tangles resulting in the closure of the company. A very high degree of liquidity is also bad; idle assets earn nothing. The firm’s funds will be unnecessarily tied up in current assets. Therefore, it is necessary to strike a proper balance between high liquidity and lack of liquidity.

The most common ratios, which indicate the extent of liquidity or lack of it, are: (i) current ratio and (ii) quick ratio. Other ratios include cash ratio, interval measure and networking capital ratio.

Current Ratio

Current ratio is calculated by dividing current assets by current liabilities:

Current assets include cash and those assets that can be converted into cash within a year, such as marketable securities, debtors and inventories. Prepaid expenses are also included in current assets as they represent the payments that will not be made by the firm in the future. All obligations maturing within a year are included in current liabilities. Current liabilities include creditors, bills payable, accrued expenses, short-term bank loan, income-tax liability and longterm debt maturing in the current year.

The current ratio is a measure of the firm’s short-term solvency. It indicates the availability of current assets in rupees for every one rupee of current liability. A ratio of greater than one means that the firm has more current assets than current claims against them.

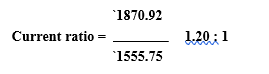

For HMC, the current ratio is:

How to interpret current ratio? As a conventional rule, a current ratio of 2 to 1 or more is considered satisfactory. The Hindustan Manufacturing Co. has a current ratio of 1.20:1; therefore, it may be interpreted to be insufficiently liquid. This rule is based on the logic that in a worse situation, even if the value of current assets becomes half, the firm will be able to meet its obligation. The current ratio represents a margin of safety for creditors. The higher the current ratio, the greater the margin of safety; the larger the amount of current assets in relation to current liabilities, the more the firm’s ability to meet its current obligations. However, an arbitrary standard of 2 to 1 should not be blindly followed. Firms with less than 2 to 1 current ratio may be doing well, while firms with 2 to 1 or even higher current ratios may be struggling to meet their obligations. This is so because the current ratio is a test of quantity, not quality. The current ratio measures only total rupees’ worth of current assets and total rupees’ worth of current liabilities. It does not measure the quality of assets. Liabilities are not subject to any fall in value; they have to be paid. But current assets can decline in value. If the firm’s current assets consist of doubtful and slow-paying debtors or slow-moving and obsolete stock of goods, then the firm’s ability to pay bills is impaired; its short-term solvency is threatened. Thus, too much reliance should not be placed on the current ratio; a further investigation about the quality of the items of current assets is necessary. However, the current ratio is a crude-and-quick measure of the firm’s liquidity.

Quick Ratio

Quick ratio, also called acid-test ratio, establishes a relationship between quick, or liquid, assets and current liabilities. An asset is liquid if it can be converted into cash immediately or reasonably soon without a loss of value. Cash is the most liquid asset. Other assets that are considered to be relatively liquid and included in quick assets are debtors and bills receivable, and marketable securities (temporary quoted investments). Inventories are considered to be less liquid.

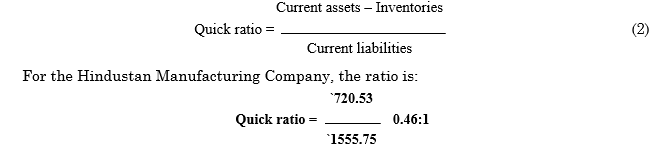

Inventories normally require some time for realizing into cash; their value also has a tendency to fluctuate. The quick ratio is found out by dividing quick assets by current liabilities.

Thus, if the HMC’s inventories do not sell, and it has to pay all its current liabilities, it may find it difficult to meet its obligations because its quick assets are 0.46 times of current liabilities.

Is quick ratio a better measure of liquidity? Generally, a quick ratio of 1 to 1 is considered to represent a satisfactory current financial condition. Although quick ratio is a more penetrating test of liquidity than the current ratio, yet it should be used cautiously. A quick ratio of 1 to 1 or more does not necessarily imply sound liquidity position. It should be remembered that all debtors may not be liquid, and cash may be immediately needed to pay operating expenses. It should also be noted that inventories are not absolutely non-liquid. To a measurable extent, inventories are available to meet current obligations. Thus, a company with a high value of quick ratio can suffer from a shortage of funds if it has slow paying, doubtful and long-duration outstanding debtors. On the other hand, a company with a low value of quick ratio may really be prospering and paying its current obligation in time if it has been turning over its inventories efficiently. Nevertheless, the quick ratio remains an important index of the firm’s liquidity.

Cash Ratio

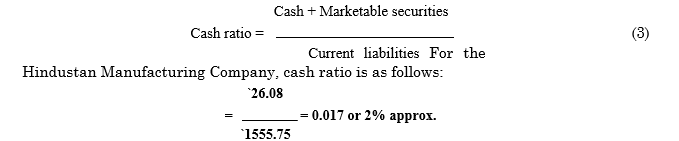

Since cash is the most liquid asset, a financial analyst may examine cash ratio and its equivalent to current liabilities. Trade investment or marketable securities are equivalent of cash; therefore, they may be included in the computation of cash ratio:

The company in our example carries a small amount of cash. There is nothing to be worried about the lack of cash if the company has reserve borrowing power. In India, firms have credit limits sanctioned from banks, and can easily draw cash.

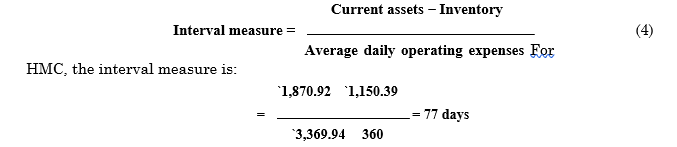

Interval Measure

Yet another ratio, which assesses a firm’s ability to meet its regular cash expenses, is the interval measure. Interval measure relates liquid assets to average daily operating cash outflows. The daily operating expenses will be equal to the cost of goods sold plus selling, administrative and general expenses less depreciation (and other non-cash expenditures) divided by number of days in the year (normally 360).

For HMC, interval measure indicates that it has sufficient liquid assets to finance its operations for 77 days, even if it does not receive any cash.

Interval measure may be refined further. Instead of calculating only the daily operating expenditures, one may also include expenditures required for paying interest, acquiring assets and repaying debt.

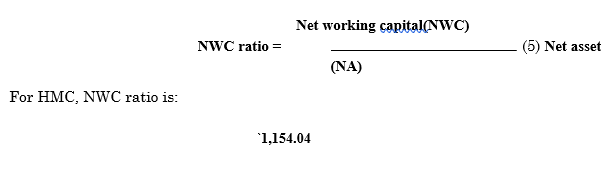

Net Working Capital Ratio

The difference between current assets and current liabilities excluding short-term bank borrowing is called net working capital (NWC) or net current assets (NCA). NWC is sometimes used as a measure of a firm’s liquidity. It is considered that, between two firms, the one having the larger NWC has the greater ability to meet its current obligations. This is not necessarily so; the measure of liquidity is a relationship, rather than the difference between current assets and current liabilities. NWC, however, measures the firm’s potential reservoir of funds. It can be related to net assets (or capital employed):

![]()

Table 20.4 presents the three-year trend of HMC’s liquidity ratios.

Table 20.4: Hindustan Manufacturing Company

Liquidity Ratios

| 20X1 | 20X2 | 20X3 | ||

| Current ratio | 1.24 | 1.25 | 1.20 | |

| Quick ratio | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.46 | |

| Cash ratio | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.02 | |

| Interval measure (days) | 65.00 | 87.00 | 77.00 | |

| Net working capital ratio | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.61 |

Ratios in Table 20.4 indicate that HMC’s liquidity is deteriorating. A note of caution may be sounded: liquidity ratio can mislead since current assets and current liabilities can change quickly. Their utility becomes more doubtful for firms with seasonal business. In the case of seasonal businesses, liquidity ratios from quarterly or monthly financial data would be more appropriate.

| Check Your Concepts

1. What is meant by liquidity ratio? What are the types of liquidity ratios? 2. How are the following ratios calculated: (a) current ratio; (b) quick ratio; (c) cash ratio; (d) net working capital ratio; (e) interval measure? 3. What is the utility of liquidity ratios? |

LEVERAGE RATIOS

The short-term creditors, like bankers and suppliers of raw material, are more concerned with the firm’s current debt-paying ability. On the other hand, long-term creditors, like debenture holders, financial institutions, etc., are more concerned with the firm’s long-term financial strength. In fact, a firm should have a strong short-as well as long-term financial position. To judge the long-term financial position of the firm, financial leverage, or capital structure ratios are calculated. These ratios indicate mix of funds provided by owners and lenders. As a general rule, there should be an appropriate mix of debt and owners’ equity in financing the firm’s assets.

The manner in which assets are financed has a number of implications. First, between debt and equity, debt is more risky from the firm’s point of view. The firm has a legal obligation to pay interest to debt holders, irrespective of the profits made or losses incurred by the firm. If the firm fails to pay to debt holders in time, they can take legal action against it to get payments and in extreme cases, can force the firm into liquidation. Second, use of debt is advantageous for shareholders in two ways: (a) they can retain control of the firm with a limited stake and (b) their earning will be magnified when the firm earns a rate of return on the total capital employed higher than the interest rate on the borrowed funds. The process of magnifying the shareholders’ return through the use of debt is called ‘financial leverage’ or ‘financial gearing’ or ‘trading on equity.’ However, leverage can work in opposite direction as well. If the cost of debt is higher than the firm’s overall rate of return, the earnings of shareholders will be reduced. In addition, there is threat of insolvency. If the firm is actually liquidated for non-payment of debt-holders’ dues, the worst sufferers will be shareholders—the residual owners. Thus, use of debt magnifies the shareholders’ earnings as well as increases their risk. Third, a highly debt-burdened firm will find difficulty in raising funds from creditors and owners in future. Creditors treat the owners’ equity as a margin of safety; if the equity base is thin, the creditors risk will be high. Thus, leverage ratios are calculated to measure the financial risk and the firm’s ability of using debt to shareholders’ advantage.

Leverage ratios may be calculated from the balance sheet items to determine the proportion of debt in total financing. Many variations of these ratios exist; but all these ratios indicate the same thing—the extent to which the firm has relied on debt in financing assets. Leverage ratios are also computed from the profit and loss items by determining the extent to which operating profits are sufficient to cover the fixed charges.

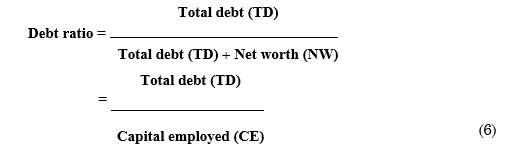

Debt Ratio

Several debt ratios may be used to analyze the long-term solvency of a firm. The firm may be interested in knowing the proportion of the interest-bearing debt (also called funded debt) in the capital structure. It may, therefore, compute debt ratio by dividing total debt (TD) by capital employed (CE) or net assets (NA). Total debt will include short and long-term borrowings from financial institutions, debentures/bonds, deferred payment arrangements for buying capital equipments, bank borrowings, public deposits and any other interest-bearing loan. Capital employed will include total debt and net worth (NW).

Note that capital employed (CE) equals net assets (NA) that consist of net fixed assets (NFA) and net current assets (NCA). Net current assets are current assets (CA) minus current liabilities (CL) excluding interest-bearing short-term debt for working capital. These relationships are:

NFA CA NW TD CL

NFA CA CL NW TD

NFA NCA NW TD

NA CE

Because of the equality of capital employed and net assets, debt ratio can also be defined as total debt divided by net assets:

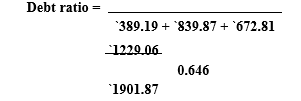

For HMC, the ratio is:

`389.19 + `839.87

The debt ratio of 0.646 means that lenders have financed 64.6 per cent or about two-thirds of HMC’s net assets (capital employed). It obviously implies that owners have provided the remaining finances. They have financed: 1 – 0.646 = 0.354 = 35.4 per cent or about one-third of net assets.

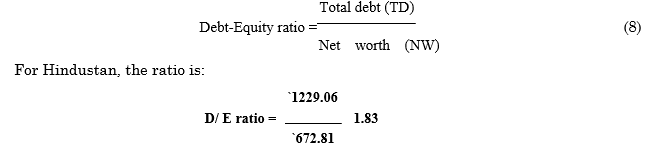

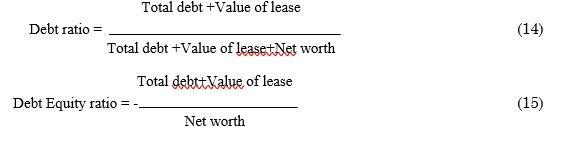

Debt-Equity Ratio

It is clear that from the total debt ratio that HMC’s lenders have contributed more funds than owners; lenders’ contribution is 1.83 times of owners’ contribution, viz., 0.646/0.354 = 1.83. This relationship describing the lenders’ contribution for each rupee of the owners’ contribution is called debt-equity ratio. Debt-equity (DE) ratio is directly computed by dividing total debt by net worth:

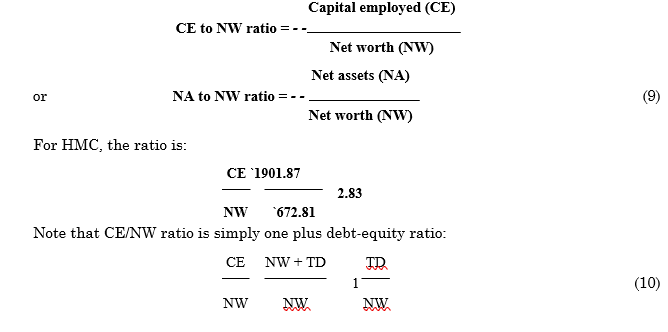

Capital employed to net worth ratio There is yet another alternative way of expressing the basic relationship between debt and equity. One may want to know: How much funds are being contributed together by lenders and owners for each rupee of the owners’ contribution? Calculating the ratio of capital employed or net assets to net worth can find this out:

Other Debt Ratios

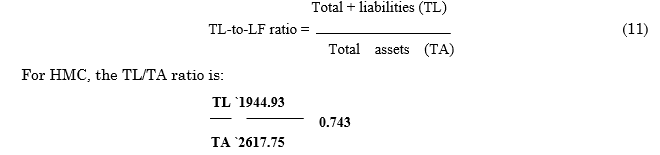

Current liabilities (non-interest bearing current obligations) are generally excluded from the computation of leverage ratios. One may like to include them on the ground that they are important determinants of the firm’s financial risk since they represent obligations and exert pressure on the firm and restrict its activities. Thus, to assess the proportion of total funds—short and long term— provided by outsiders to finance total assets, the following ratio may be calculated:

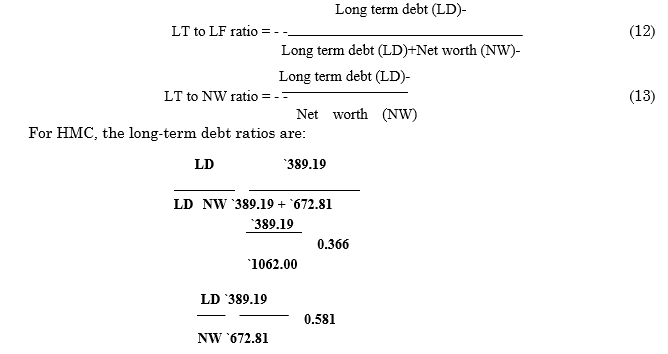

In addition to debt ratios explained so far, a firm may wish to calculate leverage ratios in terms of the long-term capitalization or funds (LTF) alone. Long-term funds or capitalization will include long-term debt and net worth. Thus, the firm may calculate the following long-term debt ratios

How to treat preference capital? Some firms have preference share capital in their capital structure. How should it be treated in computing leverage ratios? Whether the preference capital will be included in debt or net worth will depend on the purpose for which the leverage ratio is being calculated. If it is calculated to show the effect of leverage on the ordinary (or common) shareholders’ earnings, the preference capital should be included in debt. The preference dividend is fixed like the interest cost and the ordinary shareholders’ earnings will be magnified if the rate of preference dividend is less than the firm’s overall rate of return. But if the leverage ratio is calculated to reflect the financial risk, the preference capital should be included in net worth. ‘The treatment of preference share capital as debt ignores the fact that debt and preference share capital present different risk to shareholders. In one case failure to meet payments means bankruptcy and possible elimination of the common shareholders, while in the other case failure to meet payments presents no such risk.’5 In the financial analysis, leverage is seen to reflect the financial risk; therefore, preference capital should be included in net worth.

How to treat lease payments? When a company obtains the use of fixed assets under long-term lease agreements, it commits itself to a series of fixed payments (viz., lease rentals). The value of lease obligations is thus equivalent to debt. It is, therefore, natural to include the capitalized value of lease obligation in debt while measuring the firm’s financial leverage:

What do debt ratios imply? Whatever way the debt ratio is calculated, it shows the extent to which debt financing has been used in the business. A high ratio means that claims of creditors are greater than those of owners. A high level of debt introduces inflexibility in the firm’s operations due to the increasing interference and pressures from creditors. A high-debt company is able to borrow funds on very restrictive terms and conditions. The loan agreements may require a firm to maintain a certain level of working capital, or a minimum current ratio, or restrict the payment of dividends, or fix limits to the officers’ and employees’ salaries and so on. Heavy indebtedness leads to creditors’ pressures and constraints on the management’s independent functioning and energies.6 During the periods of low profits, a highly debt-financed company suffers great strains: it cannot even pay the interest charges of creditors. As a result, their pressure and control are further tightened. To meet their working capital needs, the firm finds difficulty in getting credit. It may have to borrow on highly unfavourable terms. Thus, it gets entangled in a debt trap.

A low debt-equity ratio implies a greater claim of owners than creditors. From the point of view of creditors, it represents a satisfactory situation since a high proportion of equity provides a larger margin of safety for them. During the periods of low profits, the debt servicing will prove to be less burdensome for a company with low debt–equity ratio. However, from the shareholders’ point of view, there is a disadvantage during the periods of good economic activities if the firm employs a low amount of debt. The higher the debt-equity ratio, the larger the shareholders’ earnings when the cost of debt is less than the firm’s overall rate of return on investment. Thus, there is a need to strike a proper balance between the use of debt and equity. The most appropriate debt-equity combination would involve a trade-off between return and risk.

Interpretation of debt ratio needs caution. Companies do not show some fixed obligations in the balance sheet but state them in the notes to the annual accounts. Liability arising out of the possible payment of pension benefits is an example. Similarly, some of the contingent liabilities may become real liabilities. They should not be ignored while analysing financial leverage and risk of the firm.

The three-year trend of the HMC’s leverage ratios is shown in Table 20.5.

Table 20.5: Hindustan Manufacturing Company: Leverage Ratios

| 20X1 | 20X2 | 20X3 | ||

| Total debt ratio | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.65 | |

| Debt–equity ratio | 1.26 | 1.72 | 1.83 | |

| Equity ratio | 2.26 | 2.72 | 2.83 | |

| Total liabilities ratio | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.74 | |

| Long-term debt ratio | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.37 |

HMC seems to depend more on outsiders’ funds to finance its expanding activities. The level of long-term debt is not very excessive, but the proportion of other liabilities is increasing. As much as three-fourths of the company’s assets are financed by outsiders’ money; the stake of owners is quite low in the total capital employed by the company. From the creditors’ point of view, the trend is risky and undesirable.

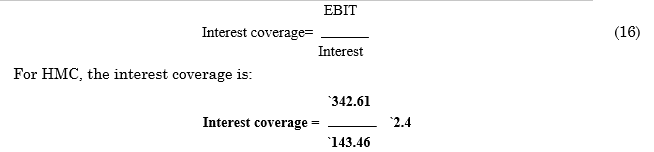

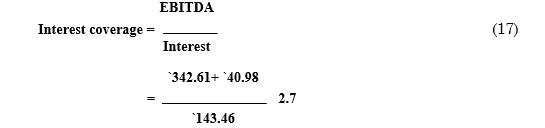

Coverage Ratios

Debt ratios described above are static in nature, and fail to indicate the firm’s ability to meet interest (and other fixed-charges) obligations. The interest coverage ratio or the times-interestearned is used to test the firm’s debt-servicing capacity. The interest coverage ratio is computed by dividing earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) by interest charges:

The interest coverage ratio shows the number of times the interest charges are covered by funds that are ordinarily available for their payment. Since taxes are computed after interest, interest coverage is calculated in relation to before-tax earnings. Depreciation is a non-cash item. Therefore, funds equal to depreciation are also available to pay interest charges. We can thus calculate the interest average ratio as earnings before interest taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) divided by interest:

This ratio indicates the extent to which earnings may fall without causing any embarrassment to the firm regarding the payment of the interest charges. A higher ratio is desirable; but too high a ratio indicates that the firm is very conservative in using debt, and that it is not using credit to the best advantage of shareholders. A lower ratio indicates excessive use of debt or inefficient operations. The firm should make efforts to improve the operating efficiency, or to retire debt to have a comfortable coverage ratio.

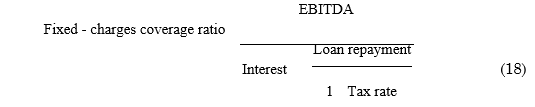

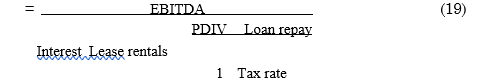

The limitation of the interest coverage ratio is that it does not consider repayment of loan. Therefore, a more inclusive ratio—the fixed-charges coverage—is calculated. This ratio is calculated by dividing EBITDA by interest plus principal repayment:

In Equation (18) all variables are on before-tax basis. Since only the after-tax earnings are available to repay principal, the principal repayment is converted to a before-tax basis by dividing it by 1 – tax rate. Depreciation and other non-cash charges are added to the numerator to provide a coverage measure in terms of cash flow rather than earnings. Equation (18) can be extended to include other fixed obligations such as preference dividends and lease rentals. Thus, the fixed-charges coverage ratio will be:

It should be obvious that a high level of debt is a problem for a company only if its future cash flows (earnings being a large component) are uncertain. An analyst, therefore, may analyze the variability of the company’s cash flows (or earnings) over time. This may be done by calculating the standard deviation of yearly changes in cash flows (or earnings) relative to the average level of cash flows (or earnings).

| Check Your Concepts

1. What is meant by leverage ratio? What are the types of leverage ratios? 2. How are the following ratios calculated: (a) debt ratio; (b) debt-equity ratio; (c) total liabilities-to total assets ratio? 3. How are coverage ratios calculated? What is its significance? 4. What purpose do leverage ratios serve? |

ACTIVITY RATIOS

Funds of creditors and owners are invested in various assets to generate sales and profits. The better the management of assets, the larger the amount of sales. Activity ratios are employed to evaluate the efficiency with which the firm manages and utilizes its assets. These ratios are also called turnover ratios because they indicate the speed with which assets are being converted or turned over into sales. Activity ratios, thus, involve a relationship between sales and assets. A proper balance between sales and assets generally reflects that assets are managed well. Several activity ratios can be calculated to judge the effectiveness of asset utilization.

Inventory Turnover

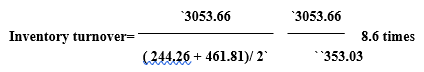

Inventory turnover indicates the efficiency of the firm in producing and selling its product. It is calculated by dividing the cost of goods sold by the average inventory:

Cost of goods sold

Inventory turnover = (20) Average inventory

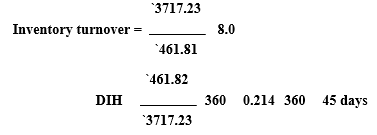

The average inventory is the average of opening and closing balances of inventory. In a manufacturing company inventory of finished goods is used to calculate inventory turnover. For HMC, the inventory turnover ratio is:

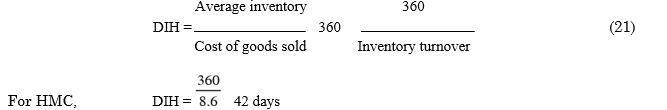

HMC is turning its inventory of finished goods into sales (at cost) 8.6 times in a year. In other words, it holds average inventory of: 12 months/8.6 = 1.4 months, or 360 days/8.6 = 42 days. The reciprocal of inventory turnover gives average inventory holdings in percentage term. When the numbers of days in a year (say, 360) are divided by inventory turnover, we obtain days of inventory holdings (DIH):

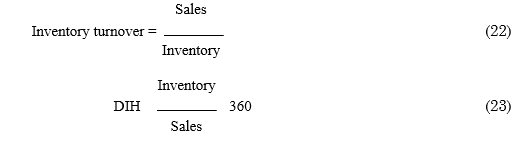

The cost of goods sold figure may not be available to an outside analyst from the published annual accounts. He/she may therefore compute inventory turnover as sales divided by the average inventory or the year-end inventory.

For HMC, the inventory turnover and DIH in terms of sales and year-end inventory are:

`3717.23

It should be noticed that Equation (20) is more logical than Equation (22) in calculating the inventory turnover. In Equation (20) both the numerator—the cost of goods sold and the denominator—the average inventory, are valued at cost and are comparable. While in Equation (22) the numerator—sales—is valued at market price and the denominator is valued at cost and is non-comparable. Further, the average inventory figure is more appropriate to use than the yearend inventory figure because the levels of inventories fluctuate over the year. The average inventory figure smoothes out the fluctuations. If the firm has a strong seasonal character, it is more desirable to take the average of the monthly inventory levels.

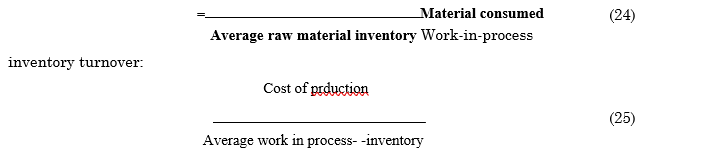

Components of inventory The manufacturing firm’s inventory consists of two more components: (i) raw materials and (ii) work-in-process. An analyst may also be interested in examining the efficiency with which the firm converts raw materials into work-in-process and work-in-process into finished goods. That is, the analyst would like to know the levels of raw materials inventory and work in process inventory held by the firm on an average. The raw material inventory should be related to materials consumed, and work-in-process to the cost of production. Thus:

Raw material inventory turnover:

Material consumed can be found out as opening balance of raw material plus purchases minus closing balance of raw material. Cost of production is determined as material consumed plus other manufacturing expenses plus opening balance minus closing balance of work-in-process. In the absence of information of material consumed or cost of production, raw material and work-inprocess inventories may be related to sales.

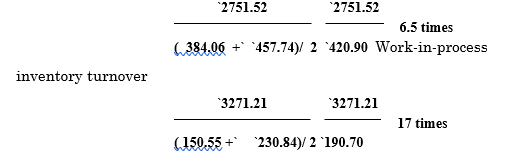

For HMC, the raw material and the work-in-process inventory turnovers are: Raw material inventory turnover

HMC’s inventories of raw material and work-in-process on an average turn, respectively, 6.5 times and 17 times in a year. Interpreted differently, the company holds 55 days’ (i.e., 360/6.5) inventory of raw material and 21 days’ (i.e., 360/17) inventory of work-in-process.

What does inventory turnover indicate? The inventory turnover shows how rapidly the inventory is turning into receivable through sales. Generally, a high inventory turnover is indicative of good inventory management. A low inventory turnover implies excessive inventory levels than warranted by production and sales activities, or a slow-moving or obsolete inventory. A high level of sluggish inventory amounts to unnecessary tie-up of funds, reduced profit and increased costs. If the obsolete inventories have to be written off, this will adversely affect the working capital and liquidity position of the firm. However, a relatively high inventory turnover should be carefully analysed. A high inventory turnover may be the result of a very low level of inventory, which results in frequent stock outs; the firm may be living from hand-to-mouth. The turnover will also be high if the firm replenishes its inventory in too many small lot sizes. The situations of frequent stock outs and too many small inventory replacements are costly for the firm. Thus, too high and too low inventory turnover ratios should be investigated further. The computation of inventory turnovers for individual components of inventory may help to detect the imbalanced investments in the various inventory components.

To judge whether HMC’s inventory turnover is good or not, it should be compared with the past and the expected ratios as well as with inventory turnover ratios of similar firms and industry average. The HMC’s trend in inventory turnover ratios is given in Table 20.6.

Table 20.6: Hindustan Manufacturing Company

Inventory Turnover Ratio

| 20X1 | 20X2 | 20X3 | |

| Finished goods turnover | 12.9 (28) | 11.9 (30) | 8.6 (42) |

| Work-in-process turnover | 27.0 (13) | 20.5 (18) | 17.1 (21) |

| Materials turnover | 6.5* (55) | 6.4 (56) | 6.5 (55) |

| Sales to total inventory | 4.9** (73) | 3.6**(100) | 3.2**(113) |

| Inventory to sales | 20.4% | 27.8% | 31.3% |

Notes: Numbers within parenthesis give number of days inventory holdings.

* Year-end inventory is used for calculating 20X1 ratio.

** Total of year-end inventory of raw material, work-in-process and finished goods are used.

HMC’s efficiency in turning its inventories is continuously deteriorating. The company’s utilization of inventories in generating sales is poor; the yearly holding of all types of inventories is increasing.

Debtors (Accounts Receivable) Turnover

A firm sells goods for cash and credit. Credit is used as a marketing tool by a number of companies. When the firm extends credits to its customers, debtors (accounts receivables) are created in the firm’s accounts. Debtors are convertible into cash over a short period and, therefore, are included in current assets. The liquidity position of the firm depends on the quality of debtors to a great extent. Financial analysts apply three ratios to judge the quality or liquidity of debtors: (a) debtors turnover, (b) collection period, (c) aging schedule of debtors.

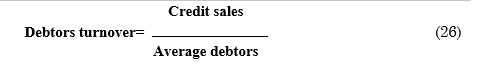

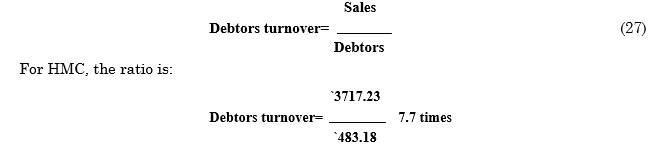

Debtors turnover Debtors turnover is found out by dividing credit sales by average debtors:

Debtors turnover indicates the number of times debtors turnover each year. Generally, the higher the value of debtors turnover, the more efficient is the management of credit.

To an outside analyst, information about credit sales and opening and closing balances of debtors may not be available. Therefore, debtors turnover can be calculated by dividing total sales by the year-end balance of debtors:

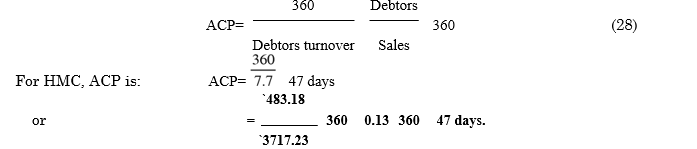

Collection period HMC is able to turnover its debtors 7.7 times in a year. In other words, its debtors remain outstanding for: 12 months/7.7 = 1.56 months or 360 days/7.7 = 47 days. The average number of days for which debtors remain outstanding is called the average collection period (ACP) and can be computed as follows:

Note that HMC’s debtors are 13 per cent of its sales. For making calculation of ACP, we have used sales for the year. It would be consistent to do so when the firm has constant sales rate throughout the year. ACP calculated on the basis of sales for the year will give a distorted and misleading picture of the firm’s collection rate if sales are seasonal or rapidly growing. ACP calculated at different points of time will vary on account of varying sales rate although there may not be any change in collection rate. Therefore, ACP in the case of seasonal or growing firms should be interpreted cautiously.

What does collection period measure? The average collection period measures the quality of debtors since it indicates the speed of their collection. The shorter the average collection period, the better the quality of debtors, since a short collection period implies the prompt payments by debtors. The average collection period should be compared against the firm’s credit terms and policy to judge its credit and collection efficiency. For example, if the credit period granted by a firm is 35 days, and its average collection period is 50 days, the comparison reveals that the firm’s debtors are outstanding for a longer period than warranted by the credit period of 35 days. An excessively long collection period implies a very liberal and inefficient credit and collection performance. This certainly delays the collection of cash and impairs the firm’s liquidity. The chances of bad debt losses are also increased. On the other hand, a low collection period is not necessarily favourable. Rather, it may indicate a very restrictive credit and collection policy. Because of the fear of bad debt losses, the firm sells only to those customers whose financial conditions are undoubtedly sound, and who are very prompt in making the payment. Such a policy succeeds in avoiding the bad debt losses, but it so severely curtails sales that overall profits are reduced. The firm should consider relaxing its credit and collection policy to enhance the sales level and improve profitability. In addition to measuring the firm’s credit-and-collection efficiency with its own credit terms, the analyst must compare the firm’s average collection period with the industry average. If there is a great divergence between the industry average and the firm’s average collection period, the analyst must investigate the causes. The investigation may reveal that the firm manages its debtors more efficiently or inefficiently than the industry, or its credit policy is too liberal or too restrictive. This may warrant a change in the credit policy. The effect of the changes in the firm’s existing credit policy on sales, profits and liquidity should be analyzed.

The collection period ratio thus helps an analyst in two respects:7

- in determining the collectibility of debtors and thus, the efficiency of collection efforts, and

- in ascertaining the firm’s comparative strength and advantage relative to its credit policy and performance vis-à-vis the competitors’ credit policies and performance.

It is useful to examine the trend in ACP to know the firm’s collection experience. HMC’s debtors turnover, ACP and debtors to sales ratio for three years are given in Table 20.7.

Table 20.7: Hindustan Manufacturing Company

Days of Sales Outstanding

| 20X1 | 20X2 | 20X3 | |

| Debtors turnover (times) | 9.2 | 8.3 | 7.7 |

| Average collection period (days) | 39 | 43 | 47 |

| Debtors/sales ratio (per cent) | 10.9 | 12.1 | 13.0 |

HMC’s average collection period has been increasing; it has increased from 39 days in 20X1 to 47 days in 20X3. This increase may be due to change in the economic conditions and/or laxity in managing receivables.

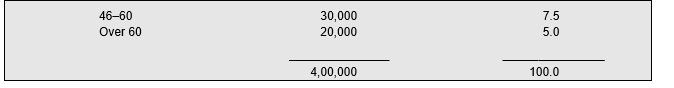

Aging schedule The average collection period measures the quality of debtors in an aggregative way. We can have a detailed idea of the quality of debtors through the aging schedule. The aging schedule breaks down debtors according to the length of time for which they have been outstanding. A hypothetical example of the aging schedule is given in Table 20.8.

The aging schedule given in Table 20.8 shows that within the collection period ranging between zero to 25 days, 50 per cent of its debtors are overdue. It also reveals that some of the accounts of the firm have serious problems of collection. The aging schedule gives more information than the collection period, and very clearly spots out the slow-paying debtors.

Table 20.8: Example of Debtors Aging Schedule

| Outstanding Period | Outstanding Amount of | Percentage of Total |

| (days) | Debtors (`) | Debtors |

| 0–25 | 2,00,000 | 50.0 |

| 26–35 | 1,00,000 | 25.0 |

| 36–45 | 50,000 | 12.5 |

(Contd…)

Assets Turnover Ratios

Assets are used to generate sales. Therefore, a firm should manage its assets efficiently to maximize sales. The relationship between sales and assets is called assets turnover. Several assets turnover ratios can be calculated.

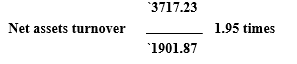

Net assets turnover The firm can compute net assets turnover simply by dividing sales by net assets (NA).

It may be recalled that net assets (NA) include net fixed assets (NFA) and net current assets (NCA), that is, current assets (CA) minus current liabilities (CL). Since net assets equal capital employed, net assets turnover may also be called capital employed turnover. For Hindustan, the ratio is

The net assets turnover of 1.95 times implies that Hindustan is producing `1.95 of sales for one rupee of capital employed in net assets.

A firm’s ability to produce a large volume of sales for a given amount of net assets is the most important aspect of its operating performance. Unutilized or under-utilized assets increase the firm’s need for costly financing as well as expenses for maintenance and upkeep. The net assets turnover should be interpreted cautiously. The net assets in the denominator of the ratio include fixed assets net of depreciation. Thus old assets with lower book (depreciated) values may create a misleading impression of high turnover without any improvement in sales.

Some analysts exclude intangible assets like goodwill, patents, etc., while computing the net assets turnover. Similarly, fictitious assets, accumulated losses or deferred expenditures may also be excluded for calculating the net assets turnover ratio.

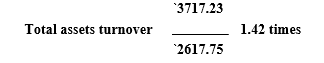

Total assets turnover Some analysts like to compute the total assets turnover in addition to or instead of the net assets turnover. This ratio shows the firm’s ability in generating sales from all financial resources committed to total assets. Thus:

Total assets

Total assets (TA) include net fixed assets (NFA) and current assets (CA) (TA = NFA + CA). For Hindustan, the ratio is:

The total assets turnover of 1.42 times implies that Hindustan generates a sale of `1.42 for one rupee investment in fixed and current assets together.

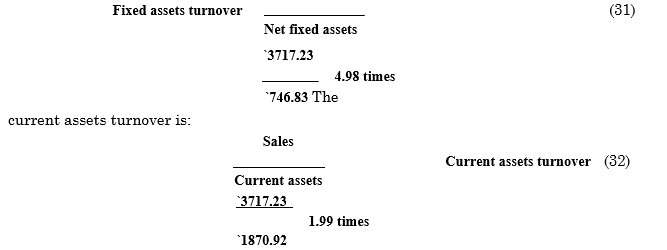

Fixed and current assets turnover The firm may wish to know its efficiency of utilizing fixed assets and current assets separately. For HMC, the fixed assets turnover is:

Sales

HMC turns over its fixed assets faster than current assets. Interpreting the reciprocals of these ratios, one may say that for generating a sale of one rupee, the company needs, respectively, `0.20 investment in fixed assets and `0.50 investment in current assets.

As explained previously, the use of depreciated value of fixed assets in computing the fixed assets turnover may render comparison of firm’s performance over a period or with other firms meaningless. Therefore, gross fixed assets (GFA) may be used to calculate the fixed assets turnover for a meaningful comparison.

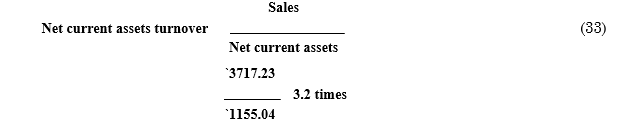

Working capital turnover A firm may also like to relate net current assets (or net working capital gap) to sales. It may thus compute net working capital turnover by dividing sales by net working capital. For HMC, the ratio is:

The reciprocal of the ratios is 0.31. Thus it is indicated that for one rupee of sales, the company needs `0.31 of net current assets. This gap will be met from bank borrowings and long-term sources of funds.

Table 20.9 gives the three-year summary of assets turnover ratios for the HMC’s turnover ratios do not show much improvement. The company has marginally improved its utilization of fixed assets, but its current assets turnover is declining.

Table 20.9: Hindustan Manufacturing Company

Assets Turnover Ratios

| 20X1 | 20X2 | 20X3 | |

| Current assets turnover (sales/CA) | 2.70(37.0) | 2.01(49.8) | 1.99(50.3) |

| Net current assets turnover (sales/NCA) | 3.85(26.0) | 3.06(32.7) | 3.22(31.1) |

| Fixed assets turnover (sales/NFA) | 4.28(23.4) | 4.26(23.5) | 4.98(20.1) |

| Total assets turnover (sales/TA) | 1.66(60.4) | 1.37(73.2) | 1.42(70.4) |

| Net assets or capital employed turnover (sales/NA) | 2.03(49.3) | 1.78(56.1) | 1.95(51.3) |

Note: Numbers in parenthesis represent assets as percentage of sales.

| Check Your Concepts

1. What is meant by activity ratio? Why are activity ratios also called turnover ratios? What are thetypes of activity ratios? 2. How are the following ratios calculated: (a) assets turnover ratio; (b) current asset turnover ratio; (c) fixed assets turnover ratio; (d) Net assets turnover ratio; and (e) net current assets turnover ratio? 3. What purpose do activity ratios serve? |

PROFITABILITY RATIOS

A company should earn profits to survive and grow over a long period of time. Profits are essential, but it would be wrong to assume that every action initiated by the management of a company should be aimed at maximizing profits, irrespective of concerns for customers, employees, suppliers or social consequences. It is unfortunate that the word ‘profit’ is looked upon as a term of abuse since some firms always want to maximize profits at the cost of employees, customers and society. Except such infrequent cases, it is a fact that sufficient profits must be earned to sustain the operations of the business to be able to obtain funds from investors for expansion and growth and to contribute towards the social overheads for the welfare of the society.8

Profit is the difference between revenues and expenses over a period of time (usually one year). Profit is the ultimate ‘output’ of a company, and it will have no future if it fails to make sufficient profits. Therefore, the financial manager should continuously evaluate the efficiency of the company in term of profits. The profitability ratios are calculated to measure the operating efficiency of the company. Besides management of the company, creditors and owners are also interested in the profitability of the firm. Creditors want to get interest and repayment of principal regularly. Owners want to get a required rate of return on their investment. This is possible only when the company earns enough profits.

Generally, two major types of profitability ratios are calculated:

- profitability in relation to sales

- profitability in relation to investment.

How is Profit Measured?

As already discussed in Chapter 2, profit can be measured in various ways. Gross profit (GP) is the difference between sales and the manufacturing cost of goods sold. A number of companies in India define gross profit differently. They define it as earnings profit before depreciation, interest and taxes (PBDIT or EBDIT). A number of multinational companies call this profit or earnings measure as earnings before interest, taxes and depreciation, and amortization or EBITDA. The most common measure of profit is profit after taxes (PAT), or net income (NI), which is a result of the impact of all factors on the firm’s earnings. Taxes are not controllable by management. To separate the influence of taxes, therefore, profit before taxes (PBT) may be computed. If the firm’s profit has to be examined from the point of view of all investors (lenders and owners), the appropriate measure of profit is operating profit. Operating profit is equivalent of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT). This measure of profit shows earnings arising directly from the commercial operations of the business without the effect of financing. The concept of EBIT may be broadened to include non-operating income if they exist. On an after-tax basis, profit to investors is equal to: EBIT (1 – T), where T is the corporate tax rate. This profit measure is called net operating profit after tax or NOPAT.

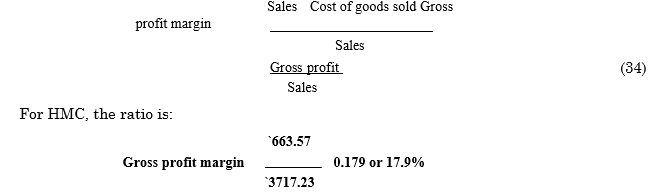

Gross Profit Margin

The first profitability ratio in relation to sales is the gross profit margin (or simply gross margin ratio9). It is calculated by dividing the gross profit by sales:

Sales Cost of goods sold Gross profit margin

The gross profit margin reflects the efficiency with which management produces each unit of product. This ratio indicates the average spread between the cost of goods sold and the sales revenue. When we subtract the gross profit margin from 100 per cent, we obtain the ratio of cost of goods sold to sales. Both these ratios show profits relative to sales after the deduction of production costs, and indicate the relation between production costs and selling price. A high gross profit margin relative to the industry average implies that the firm is able to produce at relatively lower cost.

A high gross profit margin ratio is a sign of good management. A gross margin ratio may increase due to any of the following factors;10 (i) higher sales prices, cost of goods sold remaining constant, (ii) lower cost of goods sold, sales prices remaining constant, (iii) a combination of variations in sales prices and costs, the margin widening and (iv) an increase in the proportionate volume of higher margin items. The analysis of these factors will reveal to the management how a depressed gross profit margin can be improved.

A low gross profit margin may reflect higher cost of goods sold due to the firm’s inability to purchase raw materials at favourable terms, inefficient utilization of plant and machinery, or over-investment in plant and machinery, resulting in higher cost of production. The ratio will also be low due to a fall in prices in the market, or marked reduction in selling price by the firm in an attempt to obtain large sales volume, the cost of goods sold remaining unchanged. The financial manager must be able to detect the causes of a falling gross margin and initiate action to improve the situation.

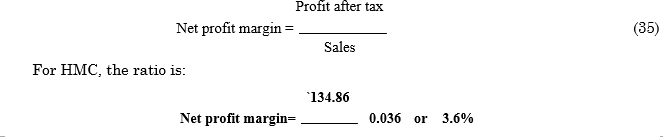

Net Profit Margin

Net profit is obtained when operating expenses, interest and taxes are subtracted from the gross profit. The net profit margin ratio is measured by dividing profit after tax by sales:

` 3717.23

If the non-operating income figure is substantial, it may be excluded from PAT to see profitability arising directly from sales. For HMC, operating profit after taxes to sales ratio is 3.6 per cent.

Net profit margin ratio establishes a relationship between net profit and sales and indicates management’s efficiency in manufacturing, administering and selling the products. This ratio is the overall measure of the firm’s ability to turn each rupee sales into net profit. If the net margin is inadequate, the firm will fail to achieve satisfactory return on shareholders’ funds.

This ratio also indicates the firm’s capacity to withstand adverse economic conditions. A firm with a high net margin ratio would be in an advantageous position to survive in the face of falling selling prices, rising costs of production or declining demand for the product. It would really be difficult for a low net margin firm to withstand these adversities. Similarly, a firm with high net profit margin can make better use of favourable conditions, such as rising selling prices, falling costs of production or increasing demand for the product. Such a firm will be able to accelerate its profits at a faster rate than a firm with a low net profit margin.

An analyst will be able to interpret the firm’s profitability more meaningfully if he/she evaluates both the ratios—gross margin and net margin—jointly. To illustrate, if the gross profit margin has increased over the years, but the net profit margin has either remained constant or declined, or has not increased as fast as the gross margin, it implies that the operating expenses relative to sales have been increasing. The increasing expenses should be identified and controlled. Gross profit margin may decline due to fall in sales price or increase in the cost of production. As a consequence, net profit margin will decline unless operating expenses decrease significantly. The crux of the argument is that both the ratios should be jointly analysed and each item of expense should be thoroughly investigated to find out the causes of decline in any or both the ratios.

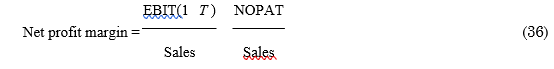

Net Margin Based on NOPAT

The profit after tax (PAT) figure excludes interest on borrowing. Interest is tax deductible, and therefore, a firm that pays more interest pays less tax. Tax saved on account of payment of interest is called interest tax shield. Thus the conventional measure of net profit margin—PAT to sales ratio—is affected by the firm’s financing policy. It can mislead if we compare two firms with different debt ratios. For a true comparison of the operating performance of firms, we must ignore the effect of financial leverage, viz., the measure of profit should ignore interest and its tax effect. Thus net profit margin (for evaluating operating performance) may be computed in the following way:11

where T is the corporate tax rate. EBIT (1 – T) is the after-tax operating profit, assuming that the firm has no debt.

We can see in Table 20.1 that the effective tax rate for the HMC in 20X3 is 32 per cent. Therefore, the net margin (modified) ratio is:

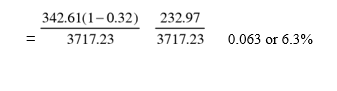

Taxes are not controllable by a firm, and also, one may not know the marginal corporate tax rate while analysing the published data. Therefore, the margin ratio may be calculated on beforetax basis:12, 13

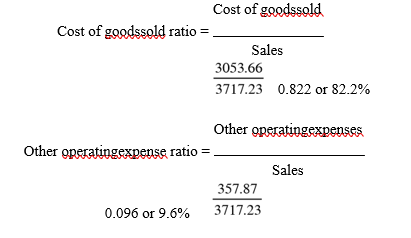

The operating ratio for HMC indicated that 91.8 per cent of sales have been consumed together by the cost of goods sold and other operating expenses. This implies that 8.2 per cent of sales is left to cover interest, taxes, and earnings to owners. Other incomes contribute about 1 per cent of sales. In practice, a firm may decompose the operating expense ratio into: (a) cost of goods sold ratio and (b) other operating expense ratio. For HMC, these ratios are calculated as follows:

What does operating expense ratio reveal? A higher operating expenses ratio is unfavourable since it will leave a small amount of operating income to meet interest, dividends, etc. To get a comprehensive idea of the behaviour of operating expenses, variations in the ratio over a number of years should be studied. Certain expenses are within the managerial discretion; therefore, it should be seen whether change in discretionary expenses is due to changes in the management policy. Detailed analysis may reveal that the year-to-year variations in the operating expense ratio are temporary in nature arising due to some temporary conditions. The variations in the ratio, temporary or long-lived, can occur due to several factors such as: (a) changes in the sales prices, (b) changes in the demand for the product, (c) changes in the administrative or selling expenses or (d) changes in the proportionate shares of sales of different products with varying gross margins. These and other causes of variations in the operating ratio should be thoroughly examined.

The operating expense ratio is a yardstick of operating efficiency, but it should be used cautiously. It is affected by a number of factors, such as external uncontrollable factors, internal factors, employees and managerial efficiency (or inefficiency), all of which are difficult to analyse. Further, the ratio cannot be used as a test of financial condition in the case of those firms where nonoperating revenue and expenses form a substantial part of the total income.

The operating expense ratio indicates the average aggregative variations in expenses, where some of the expenses may be increasing while others may be falling. Thus, to know the behaviour of specific expense items, the ratio of each individual operating expense to sales should be calculated. These ratios when compared from year to year for the firm will throw light on managerial policies and programmes. For example, the increasing selling expenses, without a sufficient increase in sales, can imply uncontrolled sales promotional expenditure, inefficiency of the marketing department, general rise in selling expenses or introduction of better substitutes by competitors. The expenses ratios of the firm should be compared with the ratios of the similar firms and the industry average. This will reveal whether the firm is paying higher or lower salaries to its employees as compared to other firms; whether its capacity utilization is high or low; whether the salesmen are given enough commission; whether it is unnecessarily spending on advertisement and other sales promotional activities; whether its cost of production is high or low and so on.

Return on Investment (ROI)

The term investment may refer to total assets or net assets. The funds employed in net assets is known as capital employed. Net assets equal net fixed assets plus current assets minus current liabilities excluding bank loans. Alternatively, capital employed is equal to net worth plus total debt.

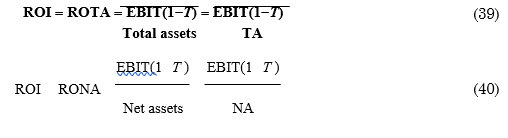

The conventional approach of calculating return on investment (ROI) is to divide PAT by investment. Investment represents pool of funds supplied by shareholders and lenders, while PAT represents residue income of shareholders; therefore, it is conceptually unsound to use PAT in the calculation of ROI. Also, as discussed earlier, PAT is affected by capital structure. It is therefore more appropriate to use one of the following measures of ROI for comparing the operating efficiency of firms:

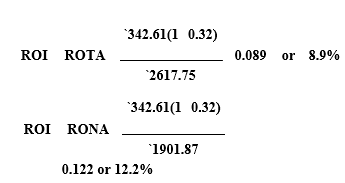

where ROTA and RONA are, respectively, return on total assets and return on net assets. RONA is equivalent of return on capital employed, i.e., ROCE. The after tax ROTA and RONA for HMC are

0.122 or 12.2%

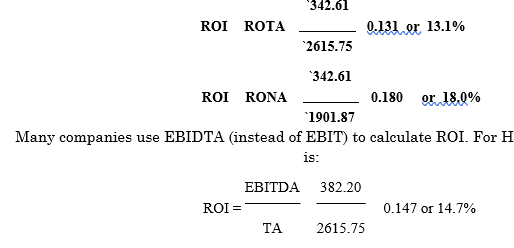

Since taxes are not controllable by management, and since firm’s opportunities for availing tax incentives differ, it may be more prudent to use before-tax measure of ROI. Thus, the beforetax ratios are:14

EBIT

ROI/ROTA (41)

TA

EBIT

ROI /RONA (42)

NA

For HMC, the before-tax ROI is:

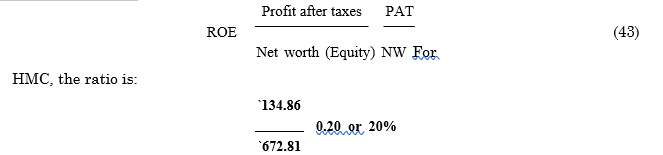

Return on Equity (ROE)

Common or ordinary shareholders are entitled to the residual profits. The rate of dividend is not fixed; the earnings may be distributed to shareholders or retained in the business. Nevertheless, the net profits after taxes represent their return. A return on shareholders’ equity is calculated to see the profitability of owners’ investment. The shareholders’ equity or net worth will include paid-up share capital, share premium and reserves and surplus less accumulated losses. Net worth can also be found by subtracting total liabilities from total assets.

The return on equity is net profit after taxes divided by shareholders’ equity which is given by net worth:15

ROE indicates how well the firm has used the resources of owners. In fact, this ratio is one of the most important relationships in financial analysis. The earning of a satisfactory return is the most desirable objective of a business. The ratio of net profit to owners’ equity reflects the extent to which this objective has been accomplished. This ratio is, thus, of great interest to the present as well as the prospective shareholders and also of great concern to the management, which has the responsibility of maximizing the owners’ welfare.

The returns on owners’ equity of the company should be compared with the ratios for other similar companies and the industry average. This will reveal the relative performance and strength of the company in attracting future investments.

The trend in sales and assets-based profitability ratios for HMC is given below:

Table 20.10: Hindustan Manufacturing Company

Profitability Ratios

| 20X1 | 20X2 | 20X3 | ||

| Gross Margin | 0.175 | 0.178 | 0.179 | |

| Net Margin | 0.036 | 0.039 | 0.036 | |

| EBIT/Sales | 0.079 | 0.094 | 0.092 | |

| PAT/Total Assets | 0.059 | 0.054 | 0.052 | |

| EBIT/Total Assets | 0.131 | 0.129 | 0.131 | |

| PAT/Net Assets | 0.072 | 0.070 | 0.071 | |

| EBIT/Net Assets | 0.161 | 0.168 | 0.180 | |

| Return on Equity | 0.164 | 0.191 | 0.200 |

It can be seen from Table 20.10 that sales as well as investment related ratios of the company have remained more or less constant. Return on equity has shown an increase. This is perhaps due to the use of more debt over years by the company.

| Check Your Concepts

1. What is meant by profitability ratio? What are the types of profitability ratios? 2. What are sales-related profitability ratios? How are they calculated? 3. How do you calculate EBIT, NOPAT and EBITDA? How do they relate to sales and assets? 4. How will you define ‘investment’ to measure investment-related profitability ratio? 5. Is it appropriate to calculate PAT-to-total or net assets ratio? Why or why not? 6. Briefly explain the significance of profitability ratios? |

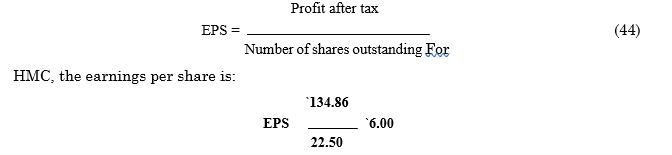

Earnings per Share (EPS)

The profitability of the shareholders’ investment can also be measured in many other ways. One such measure is to calculate the earnings per share. The earnings per share (EPS) is calculated by dividing the profit after taxes by the total number of ordinary shares outstanding.

EPS calculations made over the years indicate whether or not the firm’s earnings power on per-share basis has changed over that period. The EPS of the company should be compared with the industry average and the earnings per share of other firms. EPS simply shows the profitability of the firm on a per-share basis; it does not reflect how much is paid as dividend and how much is retained in the business. But as a profitability index, it is a valuable and widely used ratio.

Bonus and rights issues adjustment Adjustments for bonus or rights issues should be made while comparing EPS over a period of time. Bonus shares are free additional shares issued (through a transfer from reserves and surplus to the share capital) to the shareholders. The total wealth of a shareholder before or after bonus issue remains the same. Suppose the share price before bonus issue is `100, and a bonus issue of 1:3 is made. A shareholder holding 3 shares before bonus issue has a wealth of: `100 × 3 = `300. Since no cash flow takes place when bonus shares are issued his/her total wealth remains the same but is now divided into 4 shares. Thus, the share price after bonus is diluted to: `300/4 = `75 (ex-bonus price).

For a proper comparison of EPS, DPS (dividend per share), book value and share price for the periods before bonus issue, the data for the periods after bonus issue should be adjusted. For example, if a bonus issue in the proportion of 1:3 is made, then the adjustment factor 4/3 should be applied to adjust EPS of the year in which bonus issue is made as well as the subsequent years. Further, if the bonus issue, say, of 1:5 is made once again after some years, then the adjustment factor will become: 4/3 × 6/5 = 24/15 = 1.68, for the bonus year and subsequent years.

Rights issues are the shares issued to the existing shareholders of a company at a subscription price that may be different (generally lower) from the current share price. Suppose the market price of a company’s share is `100, and the subscription price per share under a rights issue is `60. The share price of `100 with the rights is called cum-rights price. Further, assume that 3 rights are needed to subscribe to one share (i.e., 1:3 rights issue). What is the implication of this for the shareholder’s wealth? Before the rights issue, the wealth of the shareholder holding 3 shares is: `100 × 3 = `300. After subscribing to the rights issue, he/she owns one additional share by paying `60. Thus, the shareholder now has a wealth of: `300 + `60 = `360 divided into 4 shares. Thus, the price per share after exercising the rights (ex-rights price) will be: `360/4 = `90. The shareholder’s existing wealth remains unchanged; he/she has paid `60 to increase his/her wealth by this amount. However, the shareholder’s proportionate ownership remains the same when he/she exercises the rights. When the rights shares have been issued, EPS, DPS, book value and share price are diluted (as the number of shares increase). To make them comparable with the data of earlier periods (before the issue of rights), they should be adjusted for the effect of the rights issue. In the example, the rights adjustment factor will be in proportion to cum-right and ex-right prices: 100/90 = 1.11.

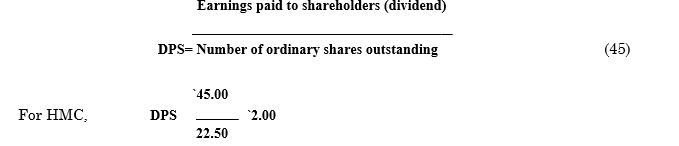

Dividend per Share (DPS or DIV)

The net profits after taxes belong to shareholders. But the income, which they really receive, is the amount of earnings distributed as cash dividends. Therefore, a large number of present and potential investors may be interested in DPS, rather than EPS. DPS is the earnings distributed to ordinary shareholders divided by the number of ordinary shares outstanding:

The company distributed `2.00 per share as dividend out of `6.00 earned per share. The difference per share is retained in the business. Like in the case of EPS, adjustments for bonus or rights issues should be made while calculating DPS over the years.

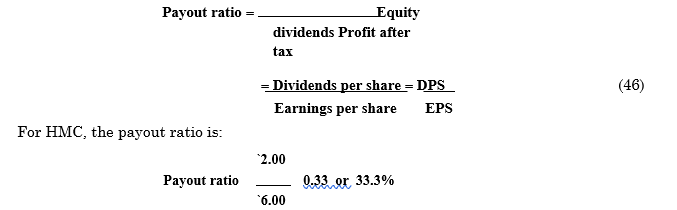

Dividend-Payout Ratio

The dividend-payout ratio or simply payout ratio is DPS (or total equity dividends) divided by the EPS (or profit after tax):

`6.00

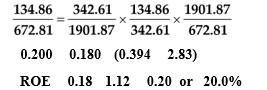

Earnings not distributed to shareholders are retained in the business. Thus retention ratio is: 1 – Payout ratio. If this figure is multiplied by the return on equity (ROE), we can know the growth in the owners’ equity as a result of retention policy. Thus, HMC, the growth in equity is:16

Growth in equity = Retention ratio × ROE

g = b × ROE (47)

For HMC, growth in equity is as follows:

g= 0.667 ¥ 0.20 = 0.133 or 13.3%

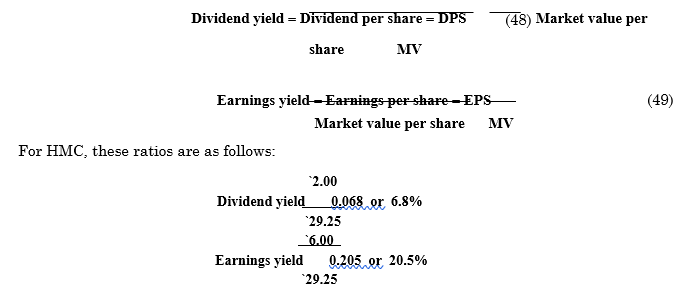

Dividend Yield and Earnings Yield

The dividend yield is the dividends per share divided by the market value per share, and the earnings yield is the earnings per share divided by the market value per share. That is:

The dividend yield and earnings yield evaluate the shareholders’ return in relation to the market value of the share. The earnings yield is also called the earnings–price (E/P) ratio. The information on the market value per share is not generally available from the financial statements; it has to be collected from external sources, such as the stock exchanges or the financial newspapers.

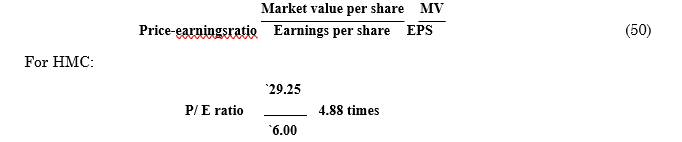

Price–Earnings Ratio

The reciprocal of the earnings yield is called the price–earnings (P/E) ratio. Thus:

The price-earnings ratio is widely used by the security analysts to value the firm’s performance as expected by investors. It indicates investors’ judgement or expectations about the firm’s performance. Management is also interested in this market appraisal of the firm’s performance and will like to find the causes if the P/E ratio declines.

P/E ratio reflects investors’ expectations about the growth in the firm’s earnings. Industries differ in their growth prospects; accordingly, the P/E ratios for industries vary widely.

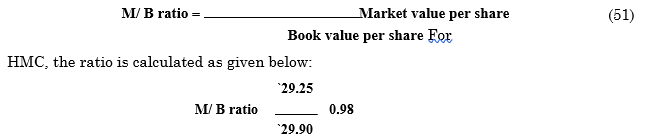

Market Value-to-Book Value (MV/BV) Ratio

Market value-to-book value (M/B) ratio is the ratio of share price to book value per share

HMC:

Note that book value per share is net worth divided by the number of shares outstanding. HMC’s M/B ratio of 0.98 means that the company is worth 2 per cent less than the funds, which shareholders have put into it.

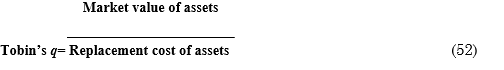

Tobin’s q

Tobin’s q is the ratio of the market value of a firm’s assets (or equity and debt) to its assets’ replacement costs. Thus

This ratio differs from the market value-to-book value ratio in two respects: it includes both debt and equity in the numerator, and all assets in the denominator, not just the book value of equity. It is argued that firms will have the incentive to invest when q is greater than 1. They will be reluctant to invest once q becomes equal to 1.17

Table 20.11 gives trend in the company’s EPS, DPS and Market-related profitability ratios.

Table 20.11: Hindustan Manufacturing Company

EPS, DPS and Market-related

Profitability Ratios (` lakh)

| 20X1 | 20X2 | 20X3 | |

| EPS (`) | 3.72 | 4.94 | 5.99 |

| DPS (`) | 1.50 | 1.75 | 2.00 |

| Market value (average) (`) | 26.38 | 34.50 | 29.25 |

| Book value (`) | 22.72 | 25.91 | 29.90 |

| Dividend payout | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.33 |

| Earnings yield | 0.141 | 0.143 | 0.205 |

| Dividend yield | 0.057 | 0.051 | 0.068 |

| P/E Ratio (times) | 7.09 | 7.00 | 4.88 |

| M/B ratio (times) | 1.16 | 1.33 | 0.98 |

It is indicated that the company’s EPS and DPS are increasing; but the proportionate increase in DPS is less than that in EPS and therefore dividend payout ratio is declining. EPS may be increasing more as a result of increasing use of debt than due to improved operations. Because of increase in the financial risk, the market price of share may come down. In spite of the increase in EPS and DPS, the market price of Hindustan’s share has declined to `29.25 in 20X3. As a result, the P/E ratio has substantially reduced to 4.88 in 20X3. The market value-to-book value ratio has also declined to 0.98. Thus, in terms of market performance, the company is showing deterioration.

| Check Your Concepts

1. What ratios are shareholders interested in? 2. How are the following ratios calculated: (a) EPS; (b) DPS; (c) market-to-book value; (d) book value per share? 3. How and why are price-earnings ratio, earnings yield and dividend yield calculated? 4. How do bonus shares and rights issues affect EPS and DPS? What adjustment is needed to be madeto compare EPS and DPS across time? |

EVALUATION OF A FIRM’S EARNING POWER: DUPONT ANALYSIS

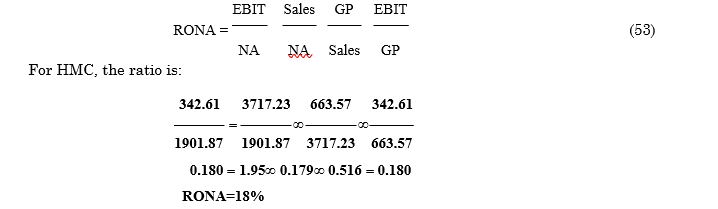

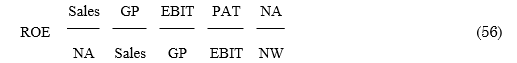

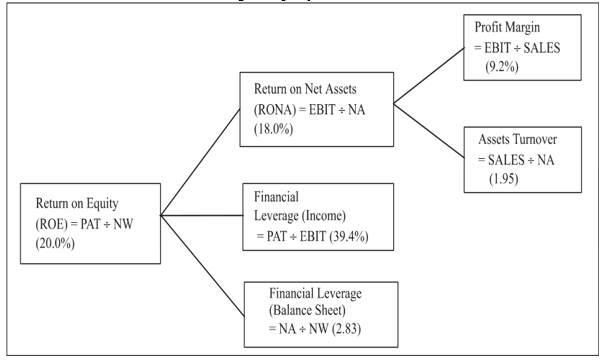

RONA (or ROCE) is the measure of the firm’s operating performance. It indicates the firm’s earning power. It is a product of the asset turnover, gross profit margin and operating leverage.18 Thus, RONA can be computed as follows:

It may be seen from Table 20.12 that HMC’s RONA has shown improvement over the years in spite of a constant gross margin and slightly declining assets turnover. RONA has increased on account of a higher operating leverage, as measured by EBIT/GP ratio, employed by the company.

All firms would like to improve their RONA. In practice, however, competition puts a limit on RONA. Also, firms may have to trade-off between asset turnover and gross profit margin. To improve profit margin, some firms resort to vertical integration for cost reduction and synergistic benefits.

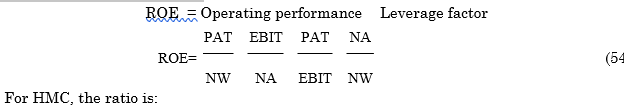

A firm can convert its RONA into an impressive ROE through financial efficiency. Financial leverage and debt-equity ratios affect ROE and reflect financial efficiency. ROE is thus a product of RONA (reflecting operating efficiency) and financial leverage ratios (reflecting financing efficiency):

For HMC, the ratio is: