INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF MANAGEMENT

Management may only have been a field of study for the last 100 years, but management principles have guided how work has been done for over 5,000 years.

From the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Chinese and Romans to modern times, leaders have used planning, organising, leading and controlling to accomplish all types of tasks, from the daily duties to large civil engineering projects.

Work has shifted from families and self-organised groups of skilled labourers, to large factories employing thousands of individuals that use large standardised mass production. As these organisations developed, managers were needed to enforce order and structure, to motivate and direct large groups of workers, and to plan and make decisions that optimised overall performance (Williams, C. 2007).

CLASSICAL MANAGEMENT THEORIES

The study of management theory began around the start of the twentieth century. Mass production and the development of large industries gave rise to demand for a way to manage these organisations and increase labour productivity.

The key elements of the classical management approach are:

- Scientific Management

- Bureaucracy Management

- Administrative Management

- Human Relations Management

Scientific Management

Fredrick Taylor (1865-1915) is credited as one of the founders of scientific management. In his book “The Principles of Scientific Management” in 1911, he emphasised the need to take a more scientific and systematic approach to management.

The main elements of Taylor’s approach were:

- A “work study” or systematic analysis of the production process followed by the breaking of jobs into a number of key tasks with each task to be performed separately.

- All planning was taken over by management, leading to workers losing control over how their work was done.

- Workers were issued with work instructions that set out:

- What needed to be done How it should be done

- How long it should take

- Select workers that were most suitable for the job and train them.

- Provide workers with financial incentives by results based payments – a piece rate system.

Scientific Management led to increased labour productivity from workers who specialised in one simple repetitive task. Replacing skilled workers with non-skilled workers could also reduce labour costs.

Scientific management could also lead to deskilling of workers that may result in dissatisfaction among workers and low levels of motivation, which could adversely affect productivity.

This approach was also accused of dehumanising of workers – treating them as if they were machines.

Scientific Management after Taylor

Three followers of scientific management were Frank and Lillian Gilbreth and Henry Gantt.

The Gilbreth’s followed on from Taylor’s work on work-study by analysing bricklayer’s movements. From their work on task or method study they were able to reduce the movements of a bricklayer. Flow charts were devised by the Gilbreths to enable whole processes or operations to be analysed.

Henry Gantt a contemporary of Taylor felt that the individual worker was not given enough consideration. Gantt introduced a payment system where performance below that described on a workers instruction card still qualified that person for the day rate but performance of all work on the instruction card qualified the individual for a bonus. The Gantt chart was initially used to graphically represent tasks achieved. See Chapter 7 for a description of a Gantt chart.

Overall the most important outcome of scientific management was that it stimulated ideas for improving the systematic analysis of work at the workplace. The disadvantage of scientific management is that it subordinated the worker to the work system.

Bureaucratic Management

Max Weber (1864-1920), a German theorist put forward the idea of the Bureaucratic organisation with its pyramid structure and chain of command with the senior manager at the top. Weber felt that bureaucracy was indispensable for the needs of large-scale organisations and that this form of organisation exists to a greater or lesser extent in practically every business and public enterprise.

The six main elements of Weber’s approach were:

- Division of Labour: The division of labour allowed specialisation, responsibility and authority to be defined, which led to increased efficiency.

- Hierarchy: Authority was centralised at the top of the organisation and positions were organised in a hierarchy structure. The degree of one’s authority depended on the position you occupied in the hierarchy.

- Selection: Weber believed that jobs should be filled according to technical skill and expertise of the individual rather than through favouritism.

- Career Orientation: Management was considered a professional career that did not necessarily involve future ownership in the company.

- Formalisation: Roles and procedures were developed to guide the way things are done, rather than ad-hoc decision-making.

- Impersonality: Rules and procedures applied to all employees regardless of their position in the hierarchy.

Today the term bureaucracy has tended to take on a negative meaning, as it is often associated with excessive administration, overstaffing, inefficiency, rigid rules and procedures.

Administrative Management

Administrative management focused on the whole organisation rather than solely on the employees. Henry Fayol (1841-1925) was one of the pioneers of administrative management. In contrast to Taylor who focused on the bottom of the organisation, Fayol’s focus was on management. The main task of the organisation head, according to Fayol, was forecasting and planning. Fayol believed that all activities in a business could be split into the following six groups:

- Technical (Production)

- Commercial (Buying and selling)

- Financial (Accessing and using capital)

- Security (Guarding property)

- Accounting (Costing and stock-taking)

- Managerial (Planning, organising, controlling, commanding and coordinating)

Fayol believed that all six groups of activities were dependent on each other, and that they all needed to be run effectively for the business to prosper.

During his career Fayol developed the following fourteen principles of management, which he believed could be applied to any organisation:

Division of Work: Specialisation leads to efficiency as workers develop practice and familiarity.

Authority and Responsibility: The right to give orders should not be considered without reference to responsibility.

Unity of command: Employees should only receive orders from one superioror a manager.

Discipline: Clear defined rules and procedures to ensure order and proper behaviour.

Unity of direction: One head and one plan for group activities.

Subordination: Subordination of the individual interest to group interest.

Remuneration: Pay should be fair and satisfactory to both the employee and the firm. Centralisation: May be present depending upon the quality of management and size of the organisation.

Scalar chain: This is the line of authority from the top of the organisation to the bottom.

Order: A place for everything and everything in its place.

Equity: A combination of kindness and justice to employees.

Stability of tenure: Employees need time to settle into their jobs and feel secure.

Initiative: All levels of the organisation’s staff should be encouraged to show initiative. Espirit de corps: Teamwork and team spirit should be encouraged.

Human Relations Theory

While the classical theorists were principally concerned with the structure and mechanics of the organisation, the theorists of the humanistic school were interested in the human factor.

The human relations movement emphasised the necessity to satisfy employees’ basic needs in order for employee productivity to be increased. They believed that if workers are happy they will work harder.

The turning point in the development of the human relations movement came with the famous Hawthorne experiments at the Western Electric Company’s Hawthorn plant in Illinois (1924-32). Elton Mayo and Fritz Roethlisberger carried out these experiments.

There were four main phases to the Hawthorne experiments:

- The illumination experiment,

- The relay assembly test room experiment,

- The interviewing programme,

- The bank wiring observation room experiment.

The illumination experiment divided the workers into two groups, an experimental and control group. Lighting levels fluctuated with one of the groups whilst the lighting with the other group remained constant.

The results of the tests were inconclusive as production in the experimental group varied without any relationship to the level of lighting, but actually increased when conditions were worse. They concluded that there was no simple cause and effect relationship between illumination and productivity and the increase in output was due to the workers being observed. This phenomenon was called the Hawthorne Effect, where workers were influenced more by psychological and social factors (observation) than by physical and logical factors (illumination).

In the relay assembly test room the work was boring and repetitive. Six women were transferred from another department to the assembly room where a number of tests were carried out including altering hours, rest periods and the provision of refreshments. The observer consulted regularly with the women, listened to their complaints, and kept them informed.

All of the changes to their conditions except one yielded an increase in production and so the conclusion drawn was that the attention paid to the workers was the main reason for the increased productivity.

The interviewing programme was conducted using prepared questions regarding workers feelings towards supervisors and their general work conditions. The result of the programme has given impetus to present day personnel management, counselling interviews and the need for management to listen to the workers.

The bank wiring observation room was centred around a group of fourteen men. It noted that the men formed their own informal organisation with sub groups or cliques. Despite financial incentive the group decided on a level of output below the level they were capable of producing; group pressures were stronger than financial incentives.

The main finding of the Hawthorn experiments is that workers increased their productivity simply because their needs were being catered for as part of the experiment. They were consulted about their part in the work and made to feel special.

Human relations writers demonstrated that people go to work to satisfy a complexity of needs and not simply for monetary reward.

Two other key contributors to the human relations approach were Abraham Maslow (19081970) and Douglas McGregor (1906- 1964).

Maslow proposed that people seek to satisfy a series of needs that range from basic needs such as food and shelter, to high level needs such as “self actualisation”. Maslow’s theory is covered in detail in Chapter 4.

McGregor questioned the assumptions made about workers in the past such as they disliked work and had to be directed and controlled. McGregor believed that organisations should harness the imagination and intellect of workers. His Theory X-Y is covered in detail in Chapter 4.

Other Contributors to the Classical Approach to the Study of Management Two other important contributions to the study of management were:

- Mary Parker Follett’s theories of constructive conflict and coordination.

- Chester Barnard’s theories of cooperation and acceptance of authority.

CONSTRUCTIVE CONFLICT AND COORDINATION: MARY PARKER FOLLETT

Mary Parker Follett is often called the “mother of management”. Her many contributions to modern management include the ideas of negotiation, conflict resolution and power sharing.

She believed that conflict could be a good thing and that it should be embraced and not avoided. She said that conflict is “the appearance of difference, difference of opinion and of interests”. She identified three ways of dealing with conflict:

- Domination: An approach to dealing with conflict in which one party deals with the conflict by satisfying its own desires and objectives at the expense of the other party’s desires and objectives.

- Compromise: An approach to dealing with conflict in which both parties deal with the conflict by giving up some of what they want in order to reach agreement on a plan by reducing or settling the conflict.

- Integrative conflict resolution: An approach to dealing with conflict in which both parties deal with the conflict by indicating their preferences and then working together to find an alternative that meets the needs of both parties.

Follett believed that integrative conflict resolution was superior to the other methods used because it focused on developing creative methods for meeting conflicting parties’ needs.

Follett used four principles to emphasise the importance of coordination where leaders and workers at different levels and in different parts of the organisation directly coordinate their efforts to solve problems and produce the best overall outcomes in an integrative way.

These principles are:

- Coordination in relation to all factors in a situation: Because most things that occur in an organisation are related, managers at different levels and at different parts of the organisation must coordinate their efforts to solve problems and produce the best overall outcome.

- Coordination by direct contact with the people concerned: Working with those involved or affected by the organisation problem or issue will produce more effective solutions.

- Coordination in the early stages: The direct contact should be early in the process before people’s views have become crystallised – they can still modify one another’s views.

- Coordination as a continuous process: The need for coordination is never ending. The very process of solving a problem is likely to result in the generation of new problems to solve.

Follett’s work significantly contributed to modern understandings of the human, social and psychological sides of management.

COOPERATION AND ACCEPTANCE OF AUTHORITY: CHESTER BARNARD

The former president of the New Jersey Bell Telephone Company, Chester Barnard, emphasised the critical importance of willing cooperation in organisations and said that managers could gain workers’ willing cooperation through three executive functions:

- Securing essential services from individuals (through material, nonmaterial and associational incentives).

- Unifying members of the organisation by clearly formulating the organisation’s purpose and objectives.

- Providing a system of communication.

Barnard’s definition of an organisation relies heavily on his comprehensive theory of cooperation. He defined an organisation as “a system of consciously coordinated activities or forces created by two or more people”.

Finally, most managerial requests or directives will be accepted because they fall within the zone of indifference, in which acceptance of managerial decisions are automatic. In general people will be indifferent to managerial directives or orders if they:

- are understood

- are consistent with the purpose of the organisation

- are compatible with the people’s personal interests

- can actually be carried out by those people

Rather than threatening workers to force cooperation, Barnard maintained that it is more effective to induce cooperation through incentives, clearly formulating organisational objectives, and effective communication throughout the organisation. Ultimately, he believes that workers grant managers their authority, not the other way around.

CONTEMPORARY MANAGEMENT THEORIES

Since the 1950s, modern approaches to the study of management have tried to build on and integrate many of the elements of the classical approaches to provide a framework for managing modern organisations. This section concentrates on the following four important approaches:

- System Theory

- Contingency Theory

- Total Quality Management

- Organisational Culture

System Theory

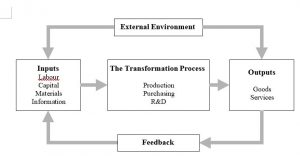

System theory focuses on the analysis of organisations as systems with a number of interrelated sub systems and also an external environment that affects organisational performance (See Figure 2.2).

One of the key elements of system theory is that the organisation should be viewed as an open system with a range of inter-dependencies and both an internal and external environment. In contrast a closed system is one which focuses only on the internal environment of the organisation. Because organisations are open systems, they need to understand and anticipate the external environment if they are to survive.

Organisations also need to consider the subsystems within the business as synergies that can be achieved when all systems are working together (the whole being greater than the sum of its parts). Another aspect of system theory is called entropy; this refers to the tendency of systems to collapse and die if they don’t receive new impetus from the external environment.

Contingency Theory

One of the limitations of many traditional management theories was that it was assumed that they apply to all situations. The contingency theory suggests that there is no single way to organise or manage. So when managers try to answer the questions outlined below, the contingency approach to management assumes there is no universal answer because organisations, people and the external environment vary widely and are constantly changing.

- Should we have a functional or divisional structure?

- Should we have narrow or wide spans of control?

- Should we have centralised or decentralised decision making?

- Should we have an organic or mechanistic structure?

- Should we have a simple versus complex control systems?

- Should we pursue a task focused or people focused style of leadership?

The contingency approach proposes the view that there are contingencies and variables that exist in most business situations and an analysis of these contingencies will assist managers in selecting the best course of action in a particular situation. The main factors or contingencies, which a manager should consider are:

- Production technology

- Size of the organisation

- Organisation structure

- Economic environment; in particular market competition and technological change

For example, according to the contingency view a stable external environment would suggest a centralised structure with an emphasis on standardised rules and procedures in order to achieve efficiency and consistency. On the other hand, an unstable environment suggests a decentralised structure to achieve flexibility and adaptability.

The most appropriate structure and systems of management are dependent upon the contingencies of the situation for each particular organisation.

Total Quality Management (TQM)

The quality movement is associated with the Japanese economic renaissance after World War II. TQM is an approach based on the use of quality concepts developed in Japan. The aim of TQM is to minimise waste and reworking by achieving zero defects in the production process.

Two of the best-known writers on the TQM approach are Deming and Juran.

Deming identified a number of points that were essential ingredients for achieving quality within the organisation. These include:

- Organisations should cease to rely on inspection to ensure quality.

- Quality should be built into every stage of the production process.

- The cause of inefficiency and poor quality lay with the systems used and not with the people using them.

- It was management’s responsibility to correct the systems in order to achieve high quality.

- Deming also stressed the importance of reducing deviations from standards. Juran believed that quality revolved around three areas:

- Quality planning to identify the key processes capable of achieving standards.

- Quality control to highlight when corrective action is necessary.

- Quality improvement to identify ways of doing things better. The TQM approach involves a number of steps:

- Find out what the customer wants,

- Design products /services that meets/exceeds customer requirements,

- Design quality into the work processes so that tasks are done correctly,

- Monitor performance,

- Expand the approach to suppliers and distributors.

Organisational Culture

An organisational culture is the shared values, beliefs and assumptions held by members of the organisation and are commonly communicated through symbolic means. Schiein (1985) defines organisational culture as:

“The pattern of basic assumptions that a given group has invented, discovered or developed in learning to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration”.

Organisational culture can be described as consisting of four layers:

- Values: These may be easy to identify in an organisation as they are often written down as statements about the organisation’s mission, objectives or strategy. However they often tend to be vague such as “service to the community”.

- Beliefs: These tend to be more specific but again there are issues, which people in the organisation can bring to the surface and talk about. They might include the belief that the company should not trade with a particular country.

- Behaviours: These are the day-to-day ways in which an organisation operates and can be seen by people both inside and outside the organisation. This includes the work routines, and how the organisation is structured and controlled.

- Taken for granted Assumptions (paradigm): These are the core of an organisation’s culture. They are the aspects of organisational life which people find difficult to identify and explain. For an organisation to operate effectively there has to be a generally accepted set of assumptions. These assumptions can underpin successful strategies and constrain the development of new strategies.

The culture of an organisation develops over time from a number of interdependent influences:

- Firstly it is developed by the prevailing national culture which influences attitudes to work, authority, equality and a number of other important factors that differ from one location to another. These values will change over time, and may even vary between different regions in larger countries. Organisations that operate internationally have the added problem of having to deal with many different national cultures.

- The second major influence is the nature of the industry, which acts as a determinant of an organisation’s culture. Specific industries contain cultural characteristics which become manifested in an organisation’s culture. Gordon (1991) argues that organisational culture is shaped by the competitive environment and the degree to which the organisation is in a monopoly situation or faced by many competitors. Similarly customer requirements in the form of reliability versus novelty shape an organisation’s culture. Finally society holds certain expectations about particular industries, which influence the values adopted.

- The final element shaping an organisation’s culture is the role of the founder of the organisation. Founder members shape organisational culture by their own cultural values, which they use to develop assumptions and theories in establishing organisations. Organisational culture is therefore developed from three interdependent sources all of which influence the beliefs, values and assumptions of the organisation.

A number of books published in the early 1980s sought to explain why some organisations were more successful than others and pointed at aspects of culture, which they argue, contributed to organisational performance.

Peters and Waterman (1982) focused on the relationship between organisation culture and performance. They chose a sample of highly successful organisations and tried to describe the management practices that led these organisations to be successful. They identified eight cultural values that led to successful management practices, which they called excellent values.

The characteristics of the excellent organisation suggested by Peters and Waterman are:

- Bias for action: Managers are expected to make decisions even if all the facts are not available.

- Stay close to the customer: Customers should be highly valued.

- Encourage autonomy and entrepreneurship: The organisation is broken into small, more manageable parts and these are encouraged to be independent, creative and risktaking.

- Encourage productivity through people: People are the organisation’s most important asset and the organisation must let them flourish.

- Hands-on management: Managers stay in touch with business activities by wandering around the organisation and not managing from behind closed doors

- Stick to the knitting: These organisations are reluctant to engage in business activities outside of the organisation’s core expertise – i.e. what it is good at.

- Simple form, lean staff: Few administrative and hierarchical layers, and small corporate staff.

- Simultaneously loosely and tightly organised: Tightly organised in that all organisational members understand and believe in the organisation’s values. At the same time, loosely organised in that the organisation has fewer administrative overheads, fewer staff members and fewer rules and procedures.

In summary, the organisational culture perspective argued that successful management resulted from the development of key cultural values rather than any innovations in structure and systems.