Aim

The aim of this subject is to ensure that students have a solid foundation in economics contributing to the development of a competent and well-rounded member of the profession. This subject embraces a knowledge of the sources, interpretations and limitations of economic/business statistics.

Learning Outcomes

On successful completion of this subject students should be able to:

- Explain economic concepts and terms and their uses and application.

- Explain the market environment and income determination.

- Analyse and discuss the impact of government policy and international economic institutions on economic issues.

- Apply micro economic techniques to interpret and explain business and consumer behaviour.

- Describe the modifying and opportunistic aspect of the particular market environment in which a firm operates.

- Discuss and analyse the factors determining the contribution of various resources to the firm’s revenue.

- Explain the upper and lower limits to income determination and the distribution of economic rents.

- Explain the national economic parameters within which business is conducted.

- Discuss the interrelationship of the various sectors within the economy.

- Describe the factors governing the operation of financial institutions and the significance of these for economic activity.

- Discuss the global forces that influence the open Rwandan economy.

The Economic Problem and Production Contents

Basic Economic Problems and Systems

Some Fundamental Questions

Choice and Opportunity Cost

Nature of Production

Economic Goods and Free Goods

Production Factors

Enterprise as a Production Factor

Fixed and Variable Factors of Production

Production Function

Total, Average and Marginal Product

Total Product

Marginal Product of Labour

Average Product of Labour

Production Possibilities

Some Assumptions Relating to the Market Economy

Consistency and Rationality

The Forces of Supply and Demand

Basic Objectives of Producers and Consumers

Consumer Sovereignty

BASIC ECONOMIC PROBLEMS AND SYSTEMS

Some Fundamental Questions

Economics is concerned with people’s efforts to make use of their available resources to maintain and develop their patterns of living according to their perceived needs and aspirations. Throughout the ages people have aspired to different lifestyles with varying degrees of success in achievement but always they have had to reconcile what they have hoped to do with the constraints imposed by the resources available within their environment. Frequently they have sought to escape from these constraints by modifying that environment or moving to a different one. The restlessness and mobility implied by this conflict between aspiration and constraint has, of course, profound social and political consequences but, as far as possible, in economics courses we limit ourselves to considering the strictly economic aspects of human society.

It is usual to identify three basic problems which all human groups have to resolve. These are:

- What, in terms of goods and/or services, should be produced

- How resources should be used in order to produce the desired goods and services

- For whom the goods and services should be produced.

These questions of production and distribution are problems because, for most human societies, people’s aspirations or wants are unlimited – we often seem to want more of everything – whereas the resources available are scarce. This term has a rather special meaning in economics. When we say that resources are scarce we do not mean necessarily that they are in short supply but that we cannot make unlimited use of them. In particular when we use, for example, land for one purpose, say as a road, then that land cannot, at the same time, be used for anything else.

Choice and Opportunity Cost

Since human wants are unlimited but resources scarce, choices have to be made. If it is not possible to have a school, hospital or housing estate all on the same piece of land, the choice of any one of these involves sacrificing the others. Suppose the community’s priorities for these three options are hospital, housing estate and then school. If it chooses to build the hospital it sacrifices the opportunity for having its next most favoured option – the housing estate. It is logical, therefore, to say that the housing estate is the opportunity cost of using the land for a hospital.

Opportunity cost is one of the most important concepts in economics and also one of the most valuable contributions that economists have made to the related disciplines of business management and politics. Awareness of opportunity cost forces us to take account of what we are sacrificing when we use our available resources for any one particular purpose and this awareness helps us to make the best use of these resources by guiding us to choose those activities, goods and services which we perceive as providing the greatest benefits compared with the opportunities we are sacrificing.

Throughout history societies have experimented with many different forms and structures for decision-making in relation to the allocation of the total resources available to the community. Through much of the twentieth century there has been conflict between the centrally planned economy, with decisions taken mostly by the Government, and the free market economy, where decisions are taken mainly by individuals and groups operating in markets where they can choose to buy or not to buy the goods and services offered by suppliers according to their own assessment of the benefits and opportunity costs of the many choices with which they are faced. In the free market economy supply, demand and prices determine what is produced, how and for whom.

NATURE OF PRODUCTION

Economic Goods and Free Goods

Goods/services are economic if scarce resources have to be used to obtain or modify them so that they are of use, i.e. have utility, for people. They are free if they can be enjoyed or used without any sacrifice of resources. The air we breathe under normal conditions is free, but not when it has to be purified or kept at a constant and bearable pressure in an airliner. Rainwater, when it falls in the open on growing crops, is free but not when it has to be carried to the crops along irrigation channels or purified to make it safe for humans to drink. Free goods are indeed very precious and people are becoming increasingly aware of the costs of destroying them by their activities, e.g. by polluting the air in the areas where we live.

Production Factors

Since there are very few free goods most have to be modified in some way before they become capable of satisfying a human want. The process of want satisfaction can also be termed the creation of utility or usefulness and is also what we understand by production. In its widest economic sense production includes any human effort directed towards the satisfaction of people’s wants. It can be as simple as picking berries or washing clothes in a stream, or as involved as manufacturing a jet airliner or performing open heart surgery.

Production is simple when it involves the use of very few scarce resources but much more involved and complex when it involves a long chain of interrelated activities and a wide range of resources.

We now need to examine this general term resources, or economic resources, more closely. The resources employed in the processes of production are usually called the factors of production and, for simplicity, these can be grouped into a few simple classifications. Economists usually identify the following production factors.

• Land

This is used in two senses:

- The space occupied to carry out any production process, e.g. space for a factory or office

- The basic resources within land, sea or air which can be extracted for productive use,

e.g. metal ores, coal and oil. Or even used for agriculture such as cassava, coffee, milk or pigs

• Labour

Any mental or physical effort used in a production process. Some economists see labour as the ultimate production factor since nothing happens without the intervention of labour. Even the most advanced computer owes its powers ultimately to some human programmer or group of programmers.

• Capital

This is also used in several senses, and again we can identify two main categories:

- Real capital consists of the tools, equipment and human skills employed in production. It can be either physical capital, e.g. factory buildings, machines or equipment, or human capital – the accumulated skill, knowledge and experience without which physical capital cannot achieve its full productive potential.

- Financial capital is the fund of money which, in a modern society, is usually needed to acquire and develop real capital, both physical and human.

Notice how closely related all the production factors are. Most production requires some combination of all the factors. Only labour can function purely on its own, if we ignore the need for space. A singer or story teller can entertain with voice alone, but will usually give more pleasure with the aid of a musical instrument and is likely to benefit from earlier investment in some kind of training. The hairdresser requires a least a pair of scissors!

Enterprise as a Production Factor

All economic texts will include land, labour and capital as factors of production. There is not quite such universal agreement over what is often described as the fourth production factor, which is most commonly termed enterprise.

The concept of enterprise as a fourth factor was developed by economists who wished to explain the creation and allocation of profit. These economists saw profit as the reward which was earned by the initiator and organiser of an economic activity – the person who had the enterprise and special quality needed to identify an unsatisfied economic want and to combine successfully the other production factors in order to supply the production to satisfy it.

In an age of the small business organisation, owned and managed by one person or family, this seemed quite a reasonable explanation. The skilled worker who gives up secure and often well-paid employment to take the risks of starting and running a business is most likely to be showing enterprise and is prepared to take risks in the hope of achieving profits above the level of his or her previous wage. Many modern firms have been formed in the recent past by initiators, innovators and risk takers of the kind that certainly fit the usual definition of the business entrepreneur. Their names appear constantly in the business press. Few would wish to deny that profit has been and often remains the spur that drives them.

Nevertheless this identification of enterprise in terms of individual risk-taking raises a great many problems when we attempt to apply it generally to the modern business environment. Much contemporary business activity is controlled by large companies such as MTN, PetroRwanda, Engen and Braliwra Ltd (Brasseries Et Limonaderies Du Rwanda SA). Who are the entrepreneurs in such organisations? Are they rewarded by profits? How do these companies recruit and foster enterprise? You, yourself, may work in a large organisation. Can you reconcile the traditional economic concept of enterprise as a factor of production with your observations of the structure of your company?

Fixed and Variable Factors of Production

Both economists and accountants make an important distinction between production factors, based on the way they can be varied as the level of production changes. To take a simple example, suppose you own a successful shop. Initially you do not employ anyone but soon find you do not have time to do everything and are losing sales because you cannot serve more than one customer at a time. So, you employ an assistant. This gives you more time and flexibility and allows you to buy better stock; your monthly sales more than double. You employ another assistant and again your sales increase. You realise, however, that you cannot go on increasing the number of assistants since space in your shop is limited and you can only meet demand in a small local market. You begin to think about opening another shop in another area.

This example helps to illustrate the difference between a production factor which you can vary as the level of production varies, i.e. a variable factor, in this case the assistants (labour), and a factor which you can only move in steps at intervals when production levels change. This latter, which in our example is the shop, i.e. land (space) and capital (the shop building and equipment), is the fixed factor.

In most examples at this level of study it is usual to regard capital as a fixed factor and labour as a variable factor. Although it is not possible to have a fraction of a worker we can think in terms of worker-hours and recognise that many workers are prepared to vary the number of hours worked per week. It is more difficult to have half a shop and even if a shop is rented rather than bought, tenancies are usually for fixed periods. It is more difficult to reduce the amount of fixed factors employed than the variable factors. When a machine or piece of equipment is bought it can only be sold at a considerable financial loss.

This distinction between fixed and variable production factors is very important, particularly when we come to examine production costs in Study Unit 4. It also gives us an important distinction in time. When analysing production, economists distinguish between the short run and the long run. By short run they mean that period during which at least one production factor, usually capital, is fixed, e.g. one shop, one factory, one passenger coach. By long run they mean that period when it is possible to vary all the factors of production, e.g. increase the number of shops, factories or passenger coaches. Sometimes you may find the short and long run referred to as short and long term.

Production Function

We can now summarise the main implications of our recognition of factors of production. We can say that to produce most goods and services we need some combination of land, capital and labour. At present we can leave out enterprise as this is difficult to quantify. In slightly more formal language we say that production is a function of land, capital and labour. Using the symbols Q for production, S for land, K for capital and L for labour, this allows us, if we wish, to use the mathematical expression: Q = f(S, K, L)

TOTAL, AVERAGE AND MARGINAL PRODUCT

Total Product

In this study unit we examine what happens when production increases in the short run, when the production factor, capital, is fixed and when the factor, labour, is variable. Once again we can take a simple example of a small business which is able to increase its use of labour. For simplicity we can use the term worker as a unit of labour, but you may wish to regard a worker as a block of worker-hours which can be varied to meet the needs of the business.

Suppose the effect of adding workers to the business is reflected by the following table, where the quantity of production is measured in units and relates to a specific period of time, say, a month. The amount of capital employed by the business is fixed.

The marginal product of labour is the change in total product resulting from a change in the amount of labour employed. It is called marginal because it is the change at the edge, and the term ‘marginal’ is used in economics to denote a change in the total of one variable which results from a single unit change in another variable. Here the total is quantity of production resulting from changes in the number of workers employed.

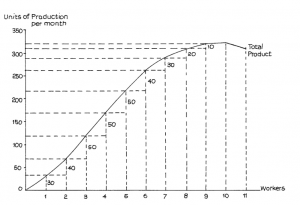

The marginal product column shows the difference in the total product column at each level of employment. Notice that the marginal value is shown midway between the values for total product and number of workers. This is because it shows the change that takes place as we move from one level of employment to the next. In Figure 1.1 the marginal product is represented by the vertical distance between each step in production as each worker is added.

The sum of the marginal product values up to each level of worker is equal to the total product at that level.

Notice how these marginal product values change as total product rises: one worker alone can produce 30 units but another enables the business to increase production by 40 units and one more by 50 units. There are many ways in which this increase might be achieved, e.g. by specialisation and by freeing the manager to improve administration, purchasing and selling. However, these increases cannot continue and the additional third, fourth and fifth workers all add a constant amount to production. Thereafter, further workers, while still increasing production, do so by diminishing amounts until the tenth worker adds nothing to the total. At this level of labour employment production has reached its maximum, and the eleventh worker actually provides a negative return – total production falls. Perhaps people get in each other’s way or cause distraction and confusion. If the business owner wishes to continue to expand production, thought must be given to increasing capital through more buildings and/or equipment. Short-run expansion at this level of capital has to cease. Only by increasing the fixed factors can further growth be achieved.

Diminishing Marginal Productivity Theory

The figures are chosen deliberately to illustrate some of the most important principles of economics, the so-called laws of varying proportions and diminishing returns. It has been constantly observed in all kinds of business activities that when further increments of one, variable production factor are added to a fixed quantity of another factor, the additional production achieved is likely, first, to increase, then to remain roughly constant and eventually to diminish. It is this third stage that is usually of the greatest importance, this is the stage of diminishing marginal product, more commonly known as diminishing returns. Most firms are likely to operate under these conditions and it is during this stage that the most difficult managerial decisions, relating to additional production and the expansion of fixed production factors, have to be taken.

The production level at which further employment ceases to be profitable depends on several other considerations, including the value of the marginal product, which depends on the revenue gained from product sales, and the cost of employing labour, made up of wages and labour taxes. The higher the cost of employing labour, the less labour will be employed in the short run and the sooner will employers seek to replace labour by capital in the form of labour-saving equipment.

Average Product of Labour

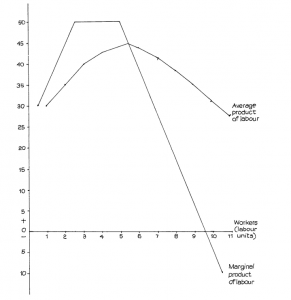

The average product of labour employed is found simply by dividing the total product at any given level of employment by the number of workers (or some unit of worker-hours). The average product of labour, though a measure easily understood and used by many business managers and their accountants, is less important than the marginal product. However, the following table adds average product to our earlier statistics, and Figure 1.2 shows both marginal and average product in graph form.

The falling marginal product curve intersects the average product curve at about the 5th worker. Average product then starts to fall because for more workers marginal product is below average product.

Notice the relationship between average and marginal product. Average product continues to rise until it is the same as the falling marginal product, then it falls.

PRODUCTION POSSIBILITIES

If individual firms are likely to face a point of maximum production as they reach the limits of their available resources the same is likely to be true of communities, whose total potential product must also be limited by the resources available to the community and by the level of technology which enables those resources to be put to productive use.

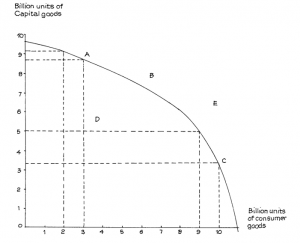

This idea is frequently illustrated by economists through what is usually termed the production possibilities frontier (or curve), which is illustrated in Figure 1.3.

The frontier represents the limit of what can be produced by a community from its available resources and at its current level of production technology. Because we wish to illustrate this through a simple two-dimensional graph we have to assume just two classes of goods and, for simplicity, we can call these consumer goods (goods and services for personal and household use) and capital goods (goods and services for use by production organisations for the production of further goods).

Because resources are scarce in the sense explained earlier in this study unit, we cannot use the same production factors to produce both sets of goods at the same time. If we want more of one set we must sacrifice some of the other set. However, the extent of the sacrifice, i.e. the opportunity cost, of increasing production of each set is unlikely to be constant through each level of production since some factors are likely to be more efficient at some kinds of production than others. Consequently the shape of the frontier curve can be assumed to reflect the principle of increasing opportunity costs. This is shown in Figure 1.3.

The curve illustrates other features of the production system. For example, the community can produce any combination of consumer and capital goods within and on the frontier but cannot produce a combination outside the frontier – say at E. If it produces the mixtures represented by points A or C on the frontier all resources (production factors) are fully employed, i.e. there are no spare or unused resources. The community can produce within the frontier, say at D, but at this point some production factors must be unemployed.

To raise production of consumer goods from 2 to 3 billion units involves sacrificing the possibility of producing 0.3 billion units of capital goods. However when production of consumer goods is 9 billion units, an additional 1 billion units involves the sacrifice of 1.6 billion units of capital goods.

The shape of the curve is based on the principle of increasing opportunity costs.

We can, of course, turn the argument round. If we know that some production factors are unemployed, e.g. if people are out of work, farm land is left uncultivated, factories and offices left empty, then we must be producing within and not on the edge of the frontier. The community is losing the opportunity of increasing its production of goods and services and is thus poorer in real terms than it need be. If, at the same time, some goods and services are in evident inadequate supply – e.g. if there are long hospital waiting lists, many families without homes, some people short of food or unable to obtain the education or training to fit them for modern life – then the production system of the community is clearly not operating efficiently to meet its expressed requirements.

Although generally used in relation to the economy as a whole the production possibilities curve can also be used to illustrate the options open to a particular firm. In this case the shape of the curve need not always follow the pattern of Figure 1.3. It might be that if the firm devoted all its resources to the production of one good instead of to more than one then it would be able to use them more efficiently. They would then gain from what will later be described as increasing returns to scale.

Yet another possibility is that the firm could switch resources without any gain or loss in efficiency, i.e. it would experience constant returns from scale in using its resources.

SOME ASSUMPTIONS RELATING TO THE MARKET ECONOMY

Consistency and Rationality

It is possible to predict with rather more confidence what groups of people are likely to do over a period of time rather than individuals. On this basis it becomes possible to estimate, for example, how many sweet potatoes will be consumed in a certain town each week or month. A supermarket manager does not know what any shopper will buy when that shopper enters the store, but can estimate how much, on average, the total number of shoppers will spend on any given day in the month and will know how much is likely to be spent on each of the many classes of goods stocked. There will be trends that will enable projections to be made into the future with some degree of confidence. As groups, therefore, people tend to be consistent and to behave according to consistent and predictable patterns and trends.

People are also assumed to be rational in their behaviour. For example if, given the choice between, say, bread and tea and sweet potatoes and porridge for breakfast we choose bread and tea and if given the choice between, say, sweet potatoes and porridge and fruit we choose sweet potatoes and porridge, then, if we are rational and offered the choice between bread and tea and fruit we would be expected to choose bread and tea, because we prefer bread and tea to sweet potatoes and porridge and sweet potatoes and porridge to fruit. It would be irrational to choose fruit in preference to bread and tea if we have already indicated a preference for sweet potatoes and porridge over fruit and for bread and tea over sweet potatoes and porridge.

If we accept consistency and rationality in human behaviour then analysis of that behaviour becomes possible, and we can start to identify patterns and trends and measure the extent to which people are likely to react to specific changes in the economic environment, such as price, in ways that we can identify, predict and measure. If we could not do this the entire study of economics would become virtually impossible.

The Forces of Supply and Demand

In studying the modern market economy we assume that the economic community is large and specialised to the extent that we can realistically separate organisations which produce goods and services from those that consume them. We are not studying village, subsistence economies which can consume only what they themselves produce. Those who have to live on what theyproduce do not have a high standard of living. We can, of course, be both producer and consumer, but the goods and services we help to produce are sold and we receive money which enables us to buy the things we wish to consume.

As individuals and members of households we are, therefore, part of the force of consumer demand. As workers and employers we are part of the separate force of production supply. Right at the start of your studies it is important to recognise that supply and demand are two separate forces. These do, of course, interact in ways that we examine in later study units but essentially they exist independently. It is quite possible for demand to exist for goods where there is no supply and only too common for goods to be supplied when there is no demand, as thousands of failed business people can testify. As students of economics you must never make the mistake of saying that supply influences demand or that demand influences supply.

Basic Objectives of Producers and Consumers

In a market economy we assume that all people wish to maximise their utility. This is simplified to suggest that producers seek to maximise profits, since the object of production for the market is to make a profit and, if given the choice between producing A or B and if A is more profitable than B, we would expect the producer to choose to produce A.

At the same time consumers can be expected to devote their resources, represented by money, to acquiring the goods and services that give them the greatest satisfaction. This is not to say that we all spend our money wisely or eat the most healthy foods or wear the most sensible clothes. We perceive satisfaction or utility in more complex ways. Economists, as economists, do not pass judgements on the wisdom or folly of particular consumer wants. They recognise that a want exists when it is clear that a significant group of people are prepared to sacrifice their resources to satisfy that want.

When this happens there is demand which can be measured and which becomes part of the total force of consumer demand.

Unfortunately this does not stop some groups of people from seeking to dictate what the rest of the community should or should not want, consume or enjoy.

Consumer Sovereignty – The Customer is King

The market economy operates on the assumption that, of supply and demand, consumer demand is dominant. Consumers decide what they want to buy and that influences suppliers; however, monopolies and advertising reduce customer sovereignty. The market production system is demand-led: supply adjusts to meet demand. In this sense the consumer is sovereign. Producers who cannot sell their goods at a profit fail and disappear from the production system. Profit is the driving force of the production system, and profit is achieved by the ability to produce goods that people will buy at prices that people will pay while enabling the producer to earn sufficient profit to stay in business – and to wish to stay in business. However strong the demand for goods, if they cannot be produced at a profit they will not, in the long run, be supplied.