INTRODUCTION

In Chapter 12, we discussed the effect of leverage on the shareholders’ earnings and risk. Under favourable economic conditions, the earnings per share increase with financial leverage. But leverage also increases the financial risk of shareholders. As a result, it cannot be stated definitely whether or not the firm’s value will increase with leverage. The objective of a firm should be directed towards the maximization of the firm’s value. The capital structure or financial leverage decision should be examined from the point of its impact on the value of the firm. If capital structure decision can affect a firm’s value, then it would like to have a capital structure, which maximizes its market value. However, there exist conflicting theories on the relationship between capital structure and the value of a firm. The traditionalists believe that capital structure affects the firm’s value while Modigliani and Miller (MM), under the assumptions of perfect capital markets and no taxes, argue that capital structure decision is irrelevant. MM reverse their position when they consider corporate taxes. Tax savings resulting from interest paid on debt create value for the firm. However, the tax advantage of debt is reduced by personal taxes and financial distress. Hence, the trade-off between costs and benefits of debt can turn capital structure into a relevant decision. There are other views also on the relevance of capital structure. We first discuss the traditional theory of capital structure followed by MM theory and other views.

| RELEVANCE OF CAPITAL STRUCTURE: |

| THE NET INCOME (NI) AND THE TRADITIONAL VIEWS |

The Net Income Approach

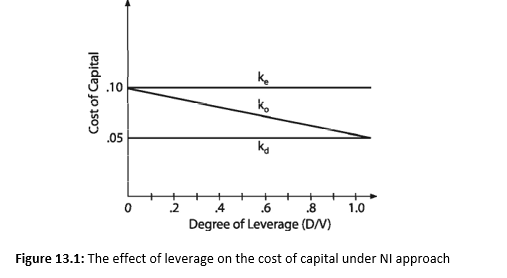

There are several variations of the traditional theory. But the thrust of all views is that capital structure matters. One earlier version of the view that capital structure is relevant is the net income (NI) approach.1 We will first discuss the NI approach, followed by other traditional views.

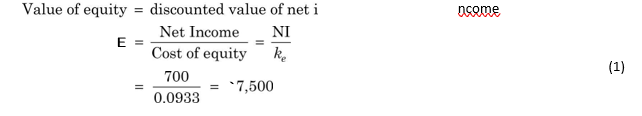

A firm that finances its assets by equity and debt is called a levered firm. On the other hand, a firm that uses no debt and finances its assets entirely by equity is called an unlevered firm. Suppose firm L is a levered firm and it has financed its assets by equity and debt. It has perpetual expected EBIT or net operating income (NOI) of `1,000 and the interest payment of `300. The firm’s cost of equity (or equity capitalization rate), ke, is 9.33 per cent and the cost of debt, kd, is 6 per cent. What is the firm’s value? The value of the firm is the sum of the values of all of its securities. In this case, firm L’s securities include equity and debt; therefore the sum of the values of equity and debt is the firm’s value. The value of a firm’s shares (equity), E, is the discounted value of shareholders’ earnings, called net income, NI. Firm L’s net income is: NOI – interest = 1,000 – 300 = `700, and the cost of equity is 9.33 per cent. Hence the value of L’s equity is: 700/0.0933 = `7,500:

Similarly the value of a firm’s debt is the discounted value of debt-holders’ interest income.

The value of L’s debt is: 300/0.06 = `5,000:

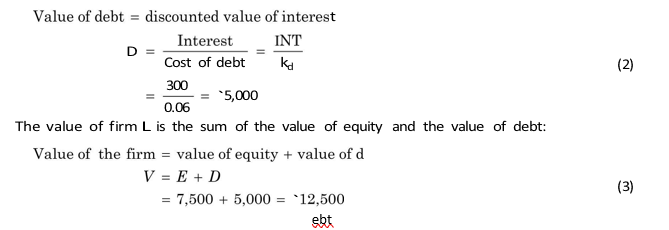

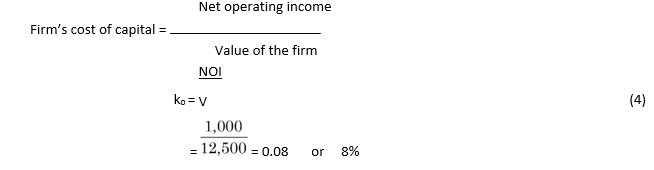

Firm’s L’s value is `12,500 and its expected net operating income is `1,000. Therefore, the firm’s overall expected rate of return or the cost of capital is:

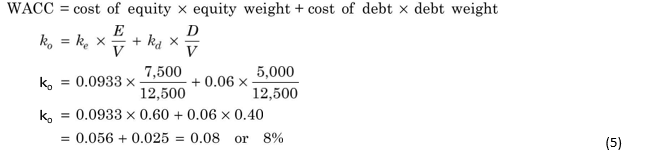

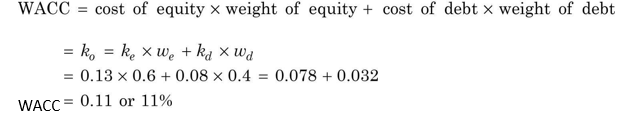

The firm’s overall cost of capital is the weighted average cost of capital (WACC). There is an alternative way of calculating WACC. WACC is the weighted average of costs of all of the firm’s securities. Firm L’s securities include debt and equity. Therefore, firm L’s WACC or ko, is the weighted average of the cost of equity and the cost of debt. Firm L’s value is `12,500, value of its equity is `7,500 and value of its debt is `5,000. Hence, the firm’s debt ratio (D/V) is: 5,000/12,500 = 0.40 or 40 per cent, and the equity ratio (E/V) is: 7,500/12,500 = 0.60 or 60 per cent. Firm L’s weighted average cost of capital is:

Suppose firm L operates in a frictionless world. That is, there are no taxes and transaction costs and debt is risk-free and shareholders perceive no financial risk arising from the use of debt. Under these conditions, the cost of equity, ke, and the cost of debt, kd, will remain constant with financial leverage. Since debt is a cheaper source of finance than equity, the firm’s weighted average cost of capital will reduce with financial leverage. Suppose firm L’s substitutes debt for equity and raises its debt ratio to 90 per cent. Its WACC will be: 0.0933 × 0.10 + 0.06 × 0.90 = 0.0633 or 6.33 per cent. Firm L’s WACC will be 6 per cent if it employs 100 per cent debt.

You may note from Equation (6) that, given the constant cost of equity, ke, and cost of debt, kd, and kd less than ke, the weighted average cost of capital, ko, will decrease continuously with financial leverage, measured by D/V. You may also notice that ko equals the cost of equity, ke, minus the spread between the cost of equity and the cost of debt multiplied by D/V. WACC, ko, will be equal to the cost of equity, ke, if the firm does not employ any debt (i. e., D/V = 0), and ko will approach kd, as D/V approaches one (or 100 per cent).

Under the assumption that ke and kd remain constant, the value of the firm will be:

The unlevered firm’s cost of equity is also its WACC and its expected net operating income is its expected net income. Hence, the value of an unlevered (an all-equity) firm is the discounted value of the net operating income. You may also notice that as the firm substitutes debt for equity and so long as ke and kd are constant, the value of the firm, V, increases.

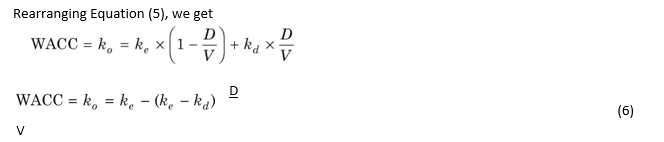

Figure 13.1 plots WACC as a function of financial leverage. Financial leverage, D/V, is plotted along the horizontal axis and WACC, ko, and the cost of equity, ke, and the cost of debt, kd, on the vertical axis. You may notice from Figure 13.1 that, under NI approach, ke and kd are constant. As debt is replaced for equity in the capital structure, being less expensive, it causes weighted average cost of capital, ko, to decrease, so that it ultimately approaches the cost of debt with 100 per cent debt ratio (D/V). The optimum capital structure occurs at the point of minimum WACC. Under the NI approach, the firm will have the maximum value and minimum WACC when it is 100 per cent debt-financed.

The Traditional View

The traditional view2 has emerged as a compromise to the extreme position taken by the NI approach. Like the NI approach, it does not assume constant cost of equity with financial leverage and continuously declining WACC. According to this view, a judicious mix of debt and equity capital can increase the value of the firm by reducing the weighted average cost of capital (WACC or k0) up to certain level of debt. This approach very clearly implies that WACC decreases only within the reasonable limit of financial leverage and after reaching the minimum level, it starts increasing with financial leverage. Hence, a firm has an optimum capital structure that occurs when WACC is minimum, and thereby maximizing the value of the firm.

Why does WACC decline under the traditional view? WACC declines with moderate level of leverage since low-cost debt is replaced for expensive equity capital. Financial leverage, resulting in risk to shareholders, will cause the cost of equity to increase. But the traditional theory assumes that at moderate level of leverage, the increase in the cost of equity is more than offset by the lower cost of debt. The assertion that debt funds are cheaper than equity funds carries the clear implication that the cost of debt plus the increased cost of equity, together on a weighted basis, will be less than the cost of equity that existed on the equity before debt financing.3 For example, suppose the cost of capital for a totally equityfinanced firm is 12 per cent. Since the firm is financed only by equity, 12 per cent is also the firm’s cost of equity (ke). The firm replaces, say, 40 per cent equity by a debt bearing 8 per cent rate of interest (cost of debt, kd). According to the traditional theory, the financial risk caused by the introduction of debt may increase the cost of equity slightly, but not so much that the advantage of cheaper debt is taken off totally. Assume that the cost of equity increases to 13 per cent. The firm’s WACC will be:

Thus, WACC will decrease with the use of debt. But as leverage increases further, shareholders start expecting higher risk premium in the form of increasing cost of equity until a point is reached at which the advantage of lower-cost debt is more than offset by more expensive equity. Let us consider an example as given in Illustration 13.2.

| ILLUSTRATION 13.2: The Traditional Theory of Capital Structure |

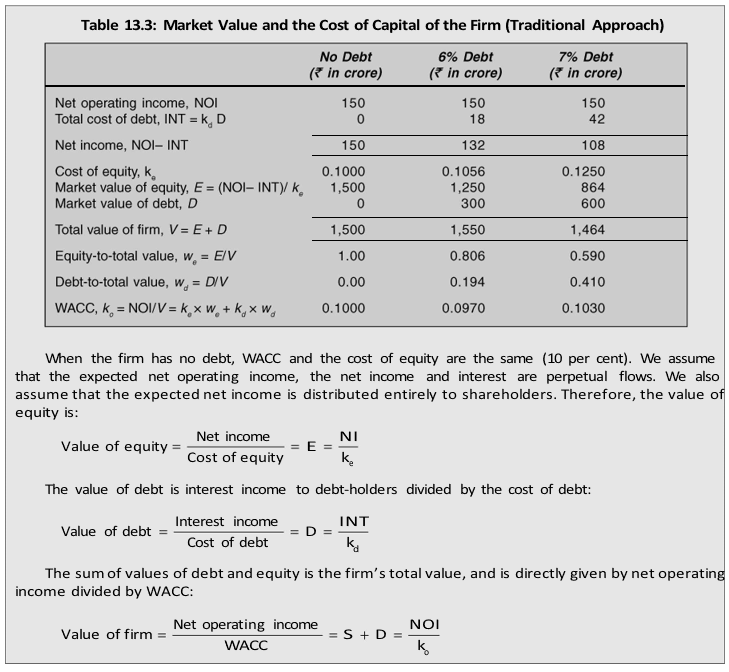

| Suppose a firm is expecting a perpetual net operating income of `150 crore on assets of `1,500 crore, which are entirely financed by equity. The firm’s equity capitalization rate (the cost of equity) is 10 per cent. It is considering substituting equity capital by issuing perpetual debentures of `300 crore at 6 per cent interest rate. The cost of equity is expected to increase to 10.56 per cent. The firm is also considering the alternative of raising perpetual debentures of `600 crore and replace equity. The debt-holders will charge interest of 7 per cent, and the cost of equity will rise to 12.5 per cent to compensate shareholders for higher financial risk. Notice that at higher level of debt (`600 crore), both the cost of equity and cost of debt increase more than at lower level of debt. The calculations for the value of the firm, the value of equity and WACC are shown in Table 13.3.

|

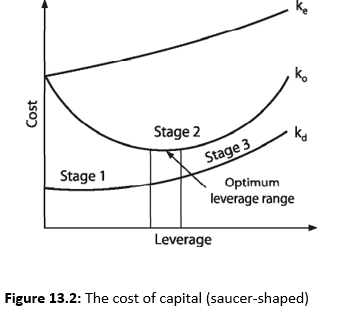

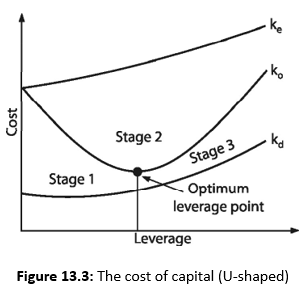

You may notice from the above discussion that, according to the traditional theory, the value of the firm may first increase with moderate leverage, reach the maximum value and then start declining with higher leverage. This is so because WACC first decreases and after reaching the minimum, it starts increasing with leverage. Thus, the traditional theory on the relationship between capital structure and the firm value has three stages.4

First stage: Increasing Value

In the first stage, the cost of equity, ke, the rate at which the shareholders capitalize their net income, either remains constant or rises slightly with debt. The cost of equity does not increase fast enough to offset the advantage of low-cost debt. During this stage, the cost of debt, kd, remains constant since the market views the use of debt as a reasonable policy. As a result, the overall cost of capital, WACC or ko, decreases with increasing leverage, and thus, the total value of the firm, V, also increases.

Second stage: Optimum Value

Once the firm has reached a certain degree of leverage, any subsequent increases in leverage have a negligible effect on WACC and hence, on the value of the firm. This is so because the increase in the cost of equity due to the added financial risk just offsets the advantage of low-cost debt. Within that range or at the specific point, WACC will be minimum, and the maximum value of the firm will be obtained.

Third stage: Declining Value

Beyond the acceptable limit of leverage, the value of the firm decreases with leverage as WACC increases with leverage. This happens because investors perceive a high degree of financial risk and demand a higher equity-capitalization rate, which exceeds the advantage of low-cost debt.

The overall effect of these three stages is to suggest that the cost of capital (WACC) is a function of leverage. It first declines with leverage and after reaching a minimum point or range, starts rising. The relation between costs of capital and leverage is graphically shown in Figure 13.2 wherein the overall cost of capital curve, ko, is saucer-shaped with a horizontal range. This implies that there is a range of capital structures in which the cost of capital is minimized. ke, is assumed to increase slightly in the beginning and then at a faster rate. In Figure 13.3 the cost of capital curve is shown as U-shaped. The U-shaped cost of capital implies that there is a precise point at which the cost of capital is minimum. This precise point defines the optimum capital structure.

As stated earlier, many variations of the traditional view exist (Figures 13.2 and 13.3). Whether the cost of equity function is horizontal or slightly rising is not very pertinent from the theoretical point of view, as a number of different costs of equity curves can be consistent with a declining average cost of capital curve. The relevant issue is whether or not the average cost of capital curve declines at all, as debt is used.5 All supporters of the traditional view agree that the cost of capital declines with debt.

Criticism of the Traditional View

The traditional theory implies that investors value levered firms more than unlevered firm. This means that they pay a premium for the shares of levered firms. The contention of the traditional theory, that moderate amount of debt in ‘sound’ firms does not really add very much to the ‘riskiness’ of the shares, is not defensible. There does not exist sufficient justification for the assumption that investors’ perception about risk of leverage is different at different levels of leverage. However, as we shall explain later, the existence of an optimum capital structure can be supported on two counts: the tax deductibility of interest charges and other market imperfections.

Check Your Concepts

- What is the net income approach of valuing a firm? What are its assumptions?

- What is the traditional approach of valuing a firm? Briefly explain the three stages of thetraditional approach.

-

IRRELEVANCE OF CAPITAL STRUCTURE: THE NET OPERATING INCOME (NOI) APPROACH What are the assumptions of the traditional approach? Are they plausible?

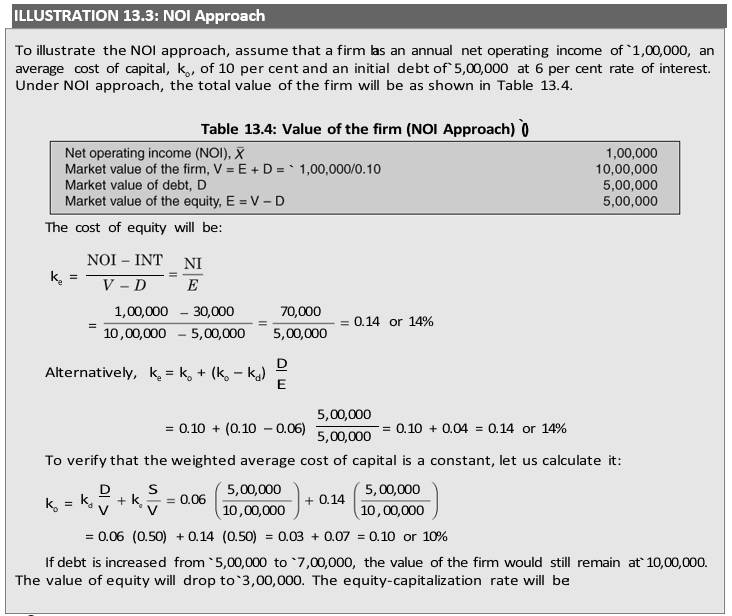

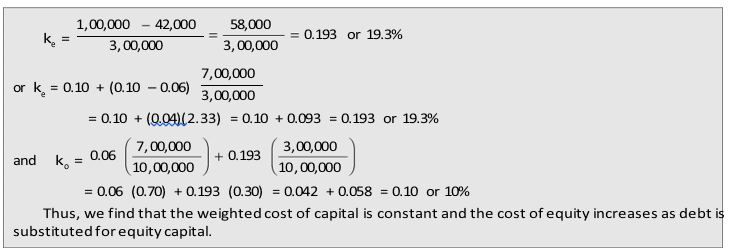

According to the net operating income (NOI) approach, the market value of the firm is not affected by the capital structure changes. The market value of the firm is found out by capitalising the net operating income at the overall, or the weighted average cost of capital, ko, which is a constant. The market value of the firm V, is determined by Equation (8):

where ko is the overall capitalization rate and depends on the business risk of the firm. It is independent of financial mix. If NOI and ko are independent of financial mix, V will be a constant and independent of capital structure changes. The critical assumptions of the NOI approach are: The market capitalizes the value of the firm as a whole. Thus, the split between debt and equity is not important.

The market uses an overall capitalization rate, ko to capitalize the net operating income. ko depends on the business risk. If the business risk is assumed to remain unchanged, ko is a constant.

The use of less costly debt funds increases the risk of shareholders. This causes the equity-capitalization rate to increase. Thus, the advantage of debt is offset exactly by the increase in the equity-capitalization rate, ke.

The debt-capitalization rate, kd, is a constant.

The corporate income taxes do not exist.

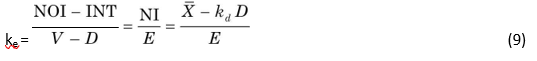

As stated above, under NOI approach, the total value of the firm is found out by dividing the net operating income by the overall cost of capital, ko. The market value of equity, E, can be determined by subtracting the value of debt, D, from the total market value of the firm V (i.e., E = V – D). The cost of equity, ke, will be measured as follows:

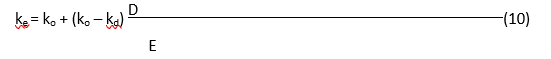

where INT is the interest charges. Alternatively, the cost of equity can be defined as follows:

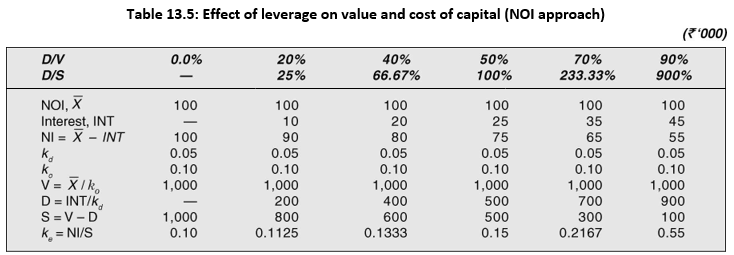

Equation (10) indicates that, if ko and kd are constant, ke would increase linearly with debt-equity ratio, D/E.

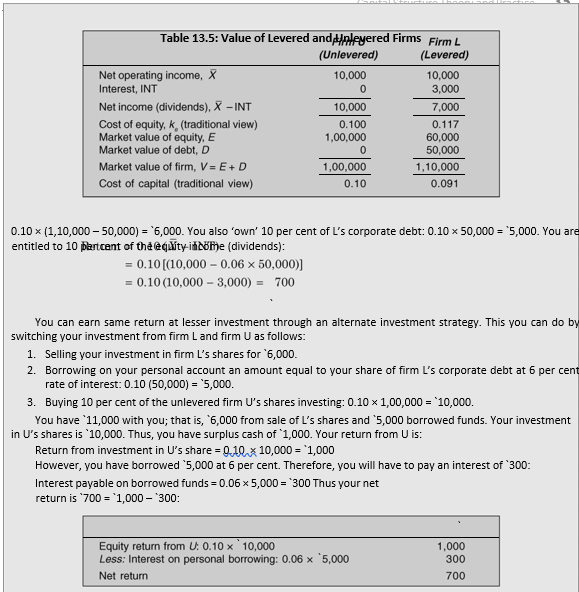

To demonstrate the effect of the various degrees of financial leverage on the value of the firm and the cost of capital under NOI approach, Table 13.5 has been constructed. The calculations in Table 13.5 are based on the following data: NOI = `1,00,000; ko = 0.10 and kd = 0.05. The firm is supposed to pay no income tax.

IRRELEVANCE OF CAPITAL STRUCTURE: THE MM HYPOTHESIS WITHOUT TAXES

Modigliani and Miller (MM) do not agree with the traditional view.6 They argue that, in perfect capital markets without taxes and transaction costs, a firm’s market value and the cost of capital remain invariant to the capital structure changes. The value of the firm depends on the earnings and risk of its assets (business risk) rather than the way in which assets have been financed. The MM hypothesis can be best explained in terms of their two propositions.

Proposition I

Consider two pharmaceutical firms, Ultrafine and Lifeline, which have identical assets, operate in same market segments and have equal market share. These two firms belong to the same industry and they face similar competitive and business conditions. Hence, they are expected to have same net operating income and exposed to similar business risk. Since the two firms have equivalent business risk, it is logical to conclude that investors’ expected rates of return from assets, ka, or the opportunity cost of capital, or the capitalization rate of the two firms, would be identical. Suppose both firms are totally equity financed and both have assets of `225 crore each. Both expect to generate net operating income of `45 crore each perpetually. Further, suppose the opportunity cost of capital or the capitalization rate for both firms is 15 per cent. Let us assume that there are no taxes so that the before and after-tax net operating income is the same. Capitalizing NOI (`45 crore) by the opportunity cost of capital (15 per cent), you can find the value of the firms. The two firms would have the same value: 45/0.15 = `300 crore.

Let us now change the assumption regarding the financing. Suppose Ultrafine is an unlevered firm with 100 per cent equity and Lifeline a levered firm with 50 per cent equity and 50 per cent debt. Should the market values of two firms differ? Debt will not change the earnings potential of Lifeline as it depends on its investment in assets. Debt also cannot affect the business conditions and therefore, the business (operating) risk of Lifeline—the levered firm. You know that the value of a firm depends upon its expected net operating income and the overall capitalization rate or the opportunity cost of capital. Since the form of financing (debt or equity) can neither change the firm’s net operating income nor its operating risk, the values of levered and unlevered firms ought be the same. Financing changes the way in which the net operating income is split or distributed between equity holders and debt-holders. Firms with identical net operating income and business (operating) risk, but differing capital structure, should have same total value. MM’s Proposition I is that, for firms in the same risk class, the total market value is independent of the debt– equity mix and is given by capitalizing the expected net operating income by the capitalization

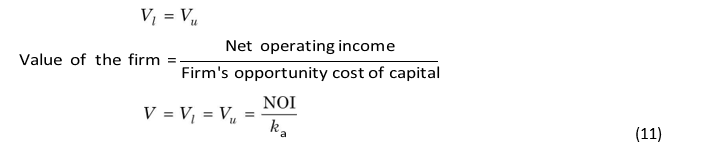

rate (i.e., the opportunity cost of capital) appropriate to that risk class:7

Value of levered firm = Value of unlevered firm

where V is the market value of the firm and it is sum of the value of equity, E, and the value of debt, D; NOI = EBIT = X, the expected net operating income; and ka = the firm’s opportunity cost of capital or the capitalization rate appropriate to the risk class of the firm.

MM’s approach is a net operating income approach because the value of the firm is the capitalized value of net operating income. Both net operating income and the firm’s opportunity cost of capital are assumed to be constant with regard to the level of financial leverage. For a levered firm, the expected net operating income is sum of the income of shareholders and the income of debt-holders. Debt-holders’ income is interest and shareholders’ income, called net income, is the expected net operating income less interest. The levered firm’s value is the sum of the value of equity and value of debt. The levered firm’s expected rate of return is the ratio of the expected operating income to the value of all its securities. This is an average expected rate of return that the levered firm’s all securityholders would require the firm to earn on total investments (assets) which we refer as ka. In fact, ka is before-tax weighted average cost of capital. Thus,

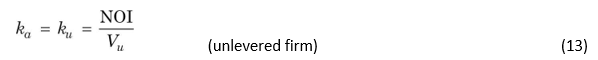

In the case of an unlevered firm, the entire net operating income is the shareholders net income. Therefore, the unlevered firm’s opportunity cost of capital ku also equals its opportunity cost of capital (that is, cost of assets, ka):

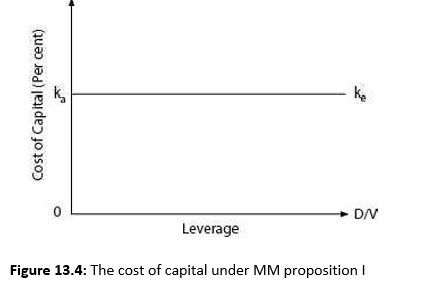

Since the values of the levered and unlevered firms and the expected net operating income (NOI) do not change with financial leverage, the opportunity cost of capital would also not change with financial leverage. Hence, MM’s Proposition I also implies that the opportunity cost of capital for two identical firms, one levered and another unlevered, will be same (Figure 13.4):

Levered firm‘s cost of capital (kl) = Unlevered firm’s cost of capital (ku)

Opportunity cost of capital = kl = ka = ku

Arbitrage Process

Why should MM’s Proposition I work? As stated earlier, the simple logic of Proposition I is that two firms with identical assets, irrespective of how these assets have been financed, cannot command different market values. Suppose this were not true and two identical firms, except for their capital structures, have different market values. In this situation, arbitrage (or switching) will take place to enable investors to engage in the personal or homemade leverage as against the corporate leverage, to restore equilibrium in the market. Consider the following example.

ILLUSTRATION 13.4: The MM Proposition I and Arbitrage

Suppose two firms—Firm U, an unlevered firm and Firm L, a levered firm—have identical assets and expected net operating income (NOI = X) of `10,000. The value of Firm L is `1,00,000 assuming the cost of equity of 10 per cent under the traditional view. Since Firm U has no debt, the value of its equity is equal to its total value (Eu = Vu). Firm L employs 6 per cent `50,000 debt. Suppose its cost of equity under the traditional view is 11.7 per cent. Thus, the value of Firm L’s equity shares (El) is `60,000, and its total value (Vl) firm is `1,10,000 (Vl = El + Dl = 60,000 + 50,000).

You may notice that Firm L and Firm U have identical assets and NOI, but they have different market prices. The cheaper debt of `50,000 of Firm L has increased shareholders wealth by `10,000. MM argue that this situation cannot continue for long, as arbitrage will bring two prices into equilibrium. How does arbitrage work?

Assume that you hold 10 per cent shares of the levered firm L. What is your return from your investment in the shares of firm L? Since you own 10 per cent of L’s shares, your equity investment is:

You earn the same return from the alternate strategy. But now you also have extra cash of `1,000 that you can invest to enhance your return. Thus, the alternate strategy will yield higher overall return. Your risk is same in both the cases. While shifting your investment from firm L to firm U, you replaced your share of L’s debt by personal debt. You have created ‘personal’ or ‘homemade leverage’ instead of ‘corporate leverage’.

Due to the advantage of the alternate investment strategy, a number of investors will be induced towards it. They will sell their shares in firm L and buy shares and debt of firm U. This arbitrage will tend to increase the price of firm U’s shares and to decline that of firm L’s shares. It will continue until the equilibrium price for the shares of firm U and firm L is reached.

The arbitrage would work in the opposite direction if we assume that the value of the unlevered firm U is greater than the value of the levered firm L (i.e., Vu > Vl). Let us assume that Vu = Eu = `100,000 and Vl = El + Dl = `40,000 + `50,000 = `90,000. Further, suppose that you still own 10 per cent shares in the unlevered firm U. Your return and investment will be:

Return = 0.10 (10,000) = `1,000

Investment = 0.10 (1,00,000) = `10,000

You can design a better investment strategy. You should do the following:

- Sell your shares in firm U for `10,000.

- Buy 10 per cent of firm L’s shares and debt:

Investment = 0.10 (40,000 + 50,000)

= 4,000 + 5,000 = `9,000

Your investment in firm L is `9,000. You have extra cash of `1,000. Since you own 10 per cent of equity and debt of firm L, your return will include both equity income and interest income. Thus your return is `1,000:

Return = 0.10 (10,000) = 0.10 (10,000 – 3,000) + 0.10 (3,000) = `1,000

Note that your alternate investment strategy pays you off the same return but at a lesser investment. Both strategies give the investor same return, but your alternate investment strategy costs you less since Vl < Vu. In such a situation, investors will sell their shares in the unlevered firm and buy the shares and debt of the levered firm. As a result of this switching, the market value of the levered firm’s shares will increase and that of the unlevered firm will decline. Ultimately, the price equilibrium will be reached (i.e., Vl = Vu) and there will be no advantage of switching anymore.

On the basis of the arbitrage process, MM conclude that the market value of a firm is not affected by leverage. Thus, the financing (or capital structure) decision is irrelevant. It does not help in creating any wealth for shareholders. Hence one capital structure is as much desirable (or undesirable) as the other.

Key Assumptions

MM’s Proposition I is based on certain assumptions. These assumptions relate to the behaviour of investors and capital markets, the actions of the firm and the tax environment.

Perfect capital markets Securities (shares and debt instruments) are traded in the perfect capital market situation. This specifically means that (a) investors are free to buy or sell securities; (b) they can borrow without restriction at the same terms as the firms do; and (c) they behave rationally. It is also implied that the transaction costs, i.e., the cost of buying and selling securities, do not exist. The assumption that firms and individual investors can borrow and lend at the same rate of interest is a very critical assumption for the validity of MM Proposition I. The homemade leverage will not be a substitute for the corporate leverage if the borrowing and lending rates for individual investors are different from firms.

Homogeneous risk classes Firms operate in similar business conditions and have similar operating risk. They are considered to have similar operating risk and belong to homogeneous risk classes when their expected earnings have identical risk characteristics. It is generally implied under the MM hypothesis that firms within same industry constitute a homogeneous class.

Risk The operating risk is defined in terms of the variability of the net operating income (NOI). The risk of investors depends on both the random fluctuations of the expected NOI and the possibility that the actual value of the variable may turn out to be different than their best estimate.8

No taxes There do not exist any corporate taxes. This implies that interest payable on debt do not save any taxes.

Full payout Firms distribute all net earnings to shareholders. This means that firms follow a 100 per cent dividend payout.

Proposition II

We have explained earlier that the value of the firm depends on the expected net operating income and the opportunity cost of capital, ka, which is same for both levered and unlevered firms. In the absence of corporate taxes, the firm’s capital structure (financial leverage) does not affect its net operating income. Hence, for the value of the firm to remain constant with financial leverage, the opportunity cost of capital, ka, must also stay constant with financial leverage. The opportunity cost of capital, ka depends on the firm’s operating risk. Since financial leverage does not affect the firm’s operating risk, there is no reason for the opportunity cost of capital, ka to change with financial leverage.

Financial leverage does not affect a firm’s net operating income, but as we have discussed in Chapter 12, it does affect shareholders’ return (EPS and ROE). EPS and ROE increase with leverage when the interest rate is less than the firm’s return on assets. Financial leverage also increases shareholders’ financial risk by amplifying the variability of EPS and ROE. Thus, financial leverage causes two opposing effects: it increases the shareholders’ return but it also increases their financial risk. Shareholders of the levered firm will increase the required rate of return (i.e., the cost of equity) on their investment to compensate for the financial risk. The higher the financial risk, the higher the shareholders’ required rate of return or the cost of equity. This is MM’s Proposition II.

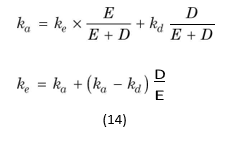

An all-equity financed or unlevered firm has no debt; its opportunity cost of capital is equal its cost of equity; that is, unlevered firm’s ke = ka. MM’s Proposition II provides justification for the levered firm’s opportunity cost of capital remaining constant with financial leverage. In simple words, it states that the cost of equity, ke, will increase enough to offset the advantage of cheaper cost of debt so that the opportunity cost of capital, ka, does not change. A levered firm has financial risk while an unlevered firm is not exposed to financial risk. Hence, a levered firm will have higher required return on equity as compensation for financial risk. The cost of equity for a levered firm should be higher than the opportunity cost of capital, ka; that is, the levered firm’s ke > ka. It should be equal to constant ka, plus a financial risk premium. How is this financial risk premium determined? You know that a levered firm’s opportunity cost of capital is the weighted average of the cost of equity and the cost of debt (no taxes assumed):

You can solve this equation to determine the levered firm’s cost of equity, ke:

You may note from the equation that for an unlevered firm, D (debt) is zero; therefore, the second part of the right-hand side of the equation is zero and the opportunity cost of capital, ka equals the cost of equity, ke. We can see from the equation that financial risk premium of a levered firm is equal to debt–equity ratio, D/E, multiplied with the spread between the constant opportunity cost of capital and the cost of debt, (ko – kd). The required return on equity is positively related to financial leverage, because the financial risk of shareholders increases with financial leverage. The cost of equity, ke, is a linear function of financial leverage, D/E. It is noteworthy that the functional relationship given in Equation (13) is valid, irrespective of any particular valuation theory. For example, MM assume the levered firm’s opportunity cost of capital or WACC to be constant, while according to the traditional view, WACC depends on financial leverage.

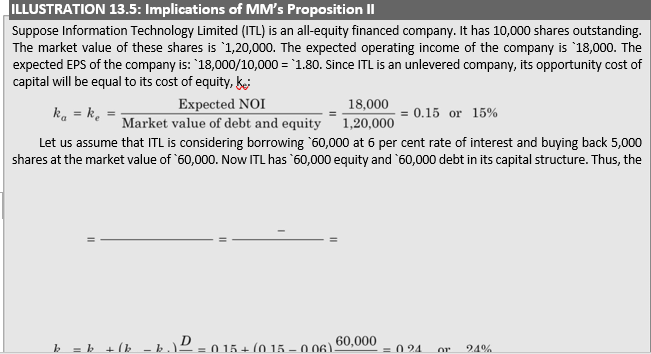

Let us consider the following example to understand the implications of MM’s Proposition II.

company’s debt-equity ratio is 1. The change in the company’s capital structure does not affect its assets and expected net operating income. However, EPS will change. The expected EPS is:

Net income 18,000 3,600

EPS `2.88

Number of shares 5,000

ITL’s expected EPS increases by 60 per cent due to financial leverage. If ITL’s expected NOI fluctuates, its EPS will show greater variability with financial leverage than as an unlevered firm. Since the firm’s operating risk does not change, its opportunity cost of capital will still remain 15 per cent. The cost of equity will increase to compensate for the financial risk:

You may notice that ka which is the before-tax weighted cost of capital will remain at 15 per cent:

E D

ka = ke V kd V = 0.24 × .50 + .06 × 0.50 = 0.15 or 15%

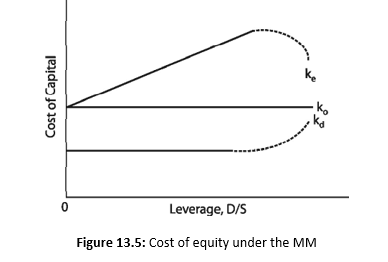

The crucial part of Proposition II is that the levered firm’s opportunity cost of capital will not rise even if very excessive use of financial leverage is made. The excessive use of debt increases the risk of default. Hence, in practice, the cost of debt, kd, will increase with high level of financial leverage. MM argue that when kd increases, ke will increase at a decreasing rate and may even turn down eventually.9 The reason for this behaviour of ke, is that debt-holders, in the extreme leveraged situations, own the firm’s assets and bear some of the firm’s business risk. Since the operating risk of shareholders is transferred to debtholders, ke declines. This is illustrated in Figure 13.5.

Criticism of the MM Hypotheses

The arbitrage process is the behavioural foundation for MM’s hypotheses. The shortcomings of this hypothesis lie in the assumption of perfect capital market in which arbitrage is expected to work. Due to the existence of imperfections in the capital market, arbitrage may fail to work and may give rise to discrepancy between the market values of levered and unlevered firms. The arbitrage process may fail to bring equilibrium in the capital market for the following reasons:10

Lending and Borrowing Rates Discrepancy

The assumption that firms and individuals can borrow and lend at the same rate of interest does not hold in practice. Because of the substantial holding of fixed assets, firms have a higher credit standing. As a result, they are able to borrow at lower rates of interest than individuals. If the cost of borrowing to an investor is more than the firm’s borrowing rate, then the equalization process will fall short of completion.

Non-substitutability of Personal and Corporate Leverages

It is incorrect to assume that ‘personal (homemade) leverage’ is a perfect substitute for ‘corporate leverage.’ The existence of limited liability of firms in contrast with unlimited liability of individuals clearly places individuals and firms on a different footing in the capital markets. If a levered firm goes bankrupt, all investors stand to lose to the extent of the amount of the purchase price of their shares. But, if an investor creates personal leverage, then in the event of the firm’s insolvency, he would lose not only his principal in the shares of the unlevered company, but will also be liable to return the amount of his personal loan. Thus, it is more risky to create personal leverage and invest in the unlevered firm than investing directly in the levered firm.

Transaction Costs

The existence of transaction costs also interferes with the working of arbitrage. Because of the costs involved in the buying and selling securities, it would become necessary to invest a greater amount in order to earn the same return. As a result, the levered firm will have a higher market value.

Institutional Restrictions

Institutional restrictions also impede the working of arbitrage. The ‘homemade’ leverage is not practically feasible as a number of institutional investors would not be able to substitute personal leverage for corporate leverage, simply because they are not allowed to engage in the ‘homemade’ leverage.

Existence of Corporate Tax

The incorporation of the corporate income taxes will also frustrate MM’s conclusions. Interest charges are tax deductible. This, in fact, means that the cost of borrowing funds to the firm is less than the contractual rate of interest. The very existence of interest charges gives the firm a tax advantage, which allows it to return to its equity and debt-holders a larger stream of income than it otherwise could have. Consider an example.

Suppose a levered and an unlevered firm have NOI = `10,000. Further, the levered firm has: kd = 0.06 and Dl = `20,000. Assume that the corporate income tax exists and the rate is 50 per cent. The unlevered firm’s after tax operating income will be: NOI – tax on NOI, i.e., 10,000 – 10,000 × 0.50 = 10,000 – 5,000 = `5000. Interest is tax exempt. Therefore, levered firm’s taxes will be less. The after-tax net operating income of the levered firm will be: NOI – tax on NOI minus interest, i.e., 10,000 – (10,000 – 1,200) × 0.50 = 10,000 – 4,400 = `5,600. Thus, the total after-tax operating earnings of debt-holders and equity holders is more in the case of the levered firm. Hence, the total market value of a levered firm should tend to exceed that of the unlevered firm for this very reason. This point is explained further in the following section.

Check Your Concepts

- What is the MM Proposition I? What are its key assumptions?

- Is there a similarity between the MM hypothesis and the net operating income approach?

- Illustrate the arbitrage process as explained by MM.

- What is the MM Proposition II? What are its implications?

- What is the criticism of the MM hypotheses without taxes?

| RELEVANCE OF CAPITAL STRUCTURE: |

| THE MM HYPOTHESIS UNDER CORPORATE TAXES |

MM’s hypothesis that the value of the firm is independent of its debt policy is based on the critical assumption that corporate income taxes do not exist. In reality, corporate income taxes exist, and interest paid to debt-holders is treated as a deductible expense. Thus, interest payable by firms saves taxes. This makes debt financing advantageous. In their 1963 article, MM show that the value of the firm will increase with debt due to the deductibility of interest charges for tax computation, and the value of the levered firm will be higher than of the unlevered firm.11 Consider an example.

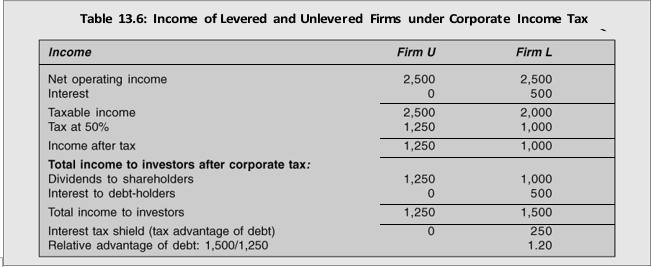

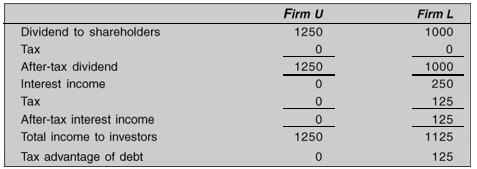

ILLUSTRATION 13.6: Debt Advantage: Interest Tax Shields

The after-tax income accruing to investors of firm L and firm U are shown in Table 13.6. You may notice that the total income available to the shareholders and debt-holders after corporate tax is `1,250 for the unlevered firm U and `1,500 for the levered firm L. Thus, the levered firm L’s investors are ahead of the unlevered firm U’s investors by `250. You may also note that the tax liability of the levered firm L is `250 less than the tax liability of the unlevered firm U. For firm L the tax savings has occurred on account of payment of interest to debt-holders. Hence, this amount is the interest tax shield or tax advantage of debt of firm L: 0.5 × (0.10 × 5,000) = 0.5 × 500 = `250. Thus, erest

Suppose two firms L and U are identical in all respects except that firm L is levered and firm U is unlevered. Firm U is an all-equity financed firm while firm L employs equity and `5,000 debt at 10 per cent rate of interest. Both firms have an expected earning before interest and taxes (or net operating income) of `2,500, pay corporate tax at 50 per cent and distribute 100 per cent earnings as dividends to shareholders.

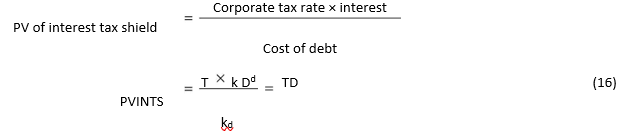

(15)

where T is the corporate tax rate, kd is the cost of debt, D is the amount of debt and kdD is the amount of interest (INT). The total after-tax income of investors of firm L is more by the amount of the interest tax shield. The levered firm’s after-tax income (Table 13.6) consists of after-tax net operating income and interest tax shield. Note that the unlevered firm is an all-equity firm and its after-tax income is just equal to the after-tax net operating income:

The after-tax income of levered firm– The after tax income of unlevered firm = interest tax shield

Value of Interest Tax Shield

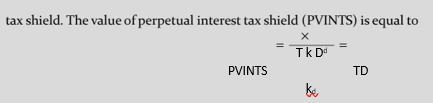

Interest tax shield is a cash inflow to the firm and therefore, it is valuable. Suppose that firm L will employ debt of `5,000 perpetually (forever). If firm L’s debt of `5,000 is permanent, then the interest tax shield of `250 is a perpetuity. What is the value of this perpetuity? For this, we need a discount rate, which reflects the riskiness of these cash flows.

The cash flows arising on account of interest tax shield are less risky than the firm’s operating income that is subject to business risk. Interest tax shield depends on the corporate tax rate and the firm’s ability to earn enough profit to cover the interest payments. The corporate tax rates do not change very frequently. Firm L can be assumed to earn at least equal to the interest payable otherwise it would not like to borrow. Thus, the cash inflows from interest tax shield can be considered less risky, and they should be discounted at a lower discount rate. It will be reasonable to assume that the risk of interest tax shield is the same as that of the interest payments generating them. Thus, the discount rate is 10 per cent, which is the rate of return required by debt-holders. The present value of the unlevered firm L’s perpetual interest tax shield of `250 is:

![]()

Thus, under the assumption of permanent debt, we can determine the present value of the interest tax shield as follows:

You may note from Equation (15) that the present value of the interest tax shields (PVINTS) is independent of the cost of debt: it is simply the corporate tax rate multiplied by the amount of permanent debt (TD). For firm L, the present value of interest tax shield can be determined as: 0.50 × 5,000 = `2,500. Note that the government, through its fiscal policy, assumes 50 per cent (the corporate tax rate) of firm L’s `5,000 debt obligation.

Value of the Levered Firm

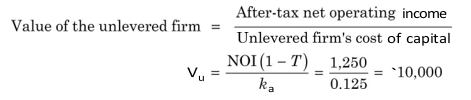

In our example, the unlevered firm U has the after-tax operating income of `1,250. Suppose the opportunity cost of capital of the unlevered firm U, ku = ka is 12.5 per cent. The value of the unlevered firm U will be `10,000:

What is the total value of the levered firm L? The after-tax income of the levered firm includes the after-tax operating income, NOI(1 – T) plus the interest tax shield, TkdD. Therefore, the value of the levered firm is the sum of the present value of the after-tax net operating income and the present value of interest tax shield. The after-tax net operating income, NOI (1 – T), of the levered firm L is equal to the after-tax income of the pure-equity (the unlevered) firm U. Hence, the opportunity cost of capital of a pure-equity firm, ku or ka, should be used to discount the stream of the after-tax operating income of the levered firm. Thus, the value of the levered firm L is equal to the value of the unlevered firm U plus the present value of the interest tax shield: d firm + PV of tax shield

We can write the formula for determining the value of the levered firm as follows:

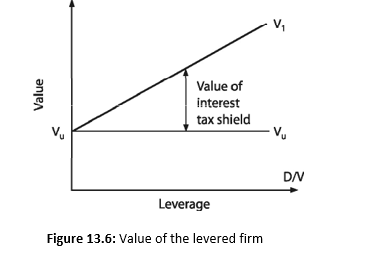

Equation (18) implies that when the corporate tax rate, T, is positive (T > 0), the value of the levered firm will increase continuously with debt. Thus, theoretically the value of the firm will be maximized when it employs 100 per cent debt. This is shown in Figure 13.6.

One significant implication of the MM hypothesis with the corporate tax in practice is that a firm without debt or with low debt can enhance its value if it exchanges debt for equity.

Personal Taxes and Capital Structure

In most countries, income from shares has no or low tax as compared to interest income. Thus, an investor has to pay more tax when her income comes in the form of interest. This will reduce the advantage of interest tax shield. How? Suppose in Illustration 13.6, there is no tax on dividend income while interest on debt is taxed at 50 per cent. Then, the total income of shareholders and debt-holders after personal taxes will be:

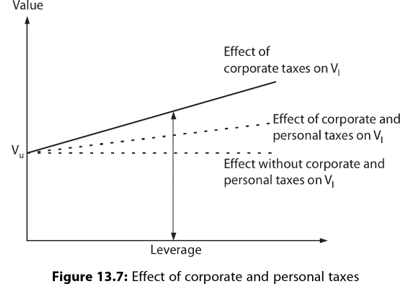

To attract investors to supply debt funds to the company, the firm will have to offer higher pre-tax interest rate, particularly to the investors in high tax brackets. By offering high interest rate to investors, the advantage arising from the interest tax shield reduces, and ultimately, the advantage will become zero. The personal taxes on interest takes away the advantage of the corporate taxes. Thus, employing debt is not so advantageous as predicted under the corporate taxes. The effect of corporate and personal taxes can be shown in Figure 13.7.

FINANCIAL DISTRESS AND OPTIMUM CAPITAL STRUCTURE

We have argued earlier that it is difficult to believe that a firm will have 100 per cent debt because of tax advantage. Why don’t firms in practice borrow 100 per cent? What are the corresponding disadvantages of debt? The disadvantages of debt are grouped under financial distress. Financial distress arises when a firm is not able to meet its obligations (payment of interest and principal) to debt-holders. The firms continuous failure to make payments to debt-holders can ultimately lead to the insolvency of the firm. For a given level of operating risk, financial distress exacerbates with higher debt. With higher business risk and higher debt, the probability of financial distress becomes much greater. The degree of business risk of a firm depends on the degree of operating leverage (i.e., the proportion of fixed costs),

general economic conditions, demand and price variations, intensity of competition, extent of diversification and the maturity of the industry. Companies operating in turbulent business environment and in highly competitive markets are exposed to higher operating risk. The operating risk is further aggravated if the companies are highly capital intensive and have high proportion of fixed costs. Matured companies with unrelated businesses are in better position to face fluctuating market conditions.

Financial distress may ultimately force a company to insolvency. Direct costs of financial distress include costs of insolvency. The proceedings to insolvency involve cumbersome process. The conflicting interests of creditors and other stakeholders can delay liquidation of the company’s assets. The physical conditions of assets, which are not in use once the insolvency proceedings start, may deteriorate over time. They may not be properly maintained. Their realizable values may decline. Finally, these assets may have to be sold at ‘distress’ prices, which may be much lower than their current values. Insolvency also causes high legal and administrative costs. The expected costs of insolvency raises the lenders’ required rate of return, which causes a dampening effect ont he market value of equity.

Financial distress, with or without insolvency, also has many indirect costs. These costs relate to the actions of employees, managers, customers, suppliers and shareholders.

In a financially distressed firm, the morale of employees is adversely affected and their productivity declines. Customers get concerned about the quality and after-sale services. Suppliers curtail supplies. Shareholders start withdrawing their investments by selling off shares and managers expropriate the firm’s resources.

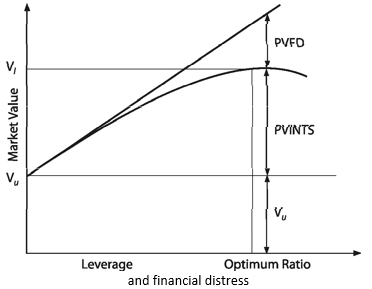

Financial distress reduces the value of the firm. Thus,the value of a levered firm is given as follows:

Vl = Vu + PVINTS – PVFD (19)

Value of levered firm = Value of unlevered firm +PV of interest tax shield –PV of financial distress.

Figure 13.8 shows how the capital structure of the firm is determined as a result of the tax benefits and the costs of financial distress. The present value of the interest tax shield increases with borrowing but so does the present value of the costs of financial distress. However, the costs of financial distress are quite insignificant with moderate level of debt, and therefore, the value of the firm increases with debt. With more and more debt, the costs of financial distress increases and therefore, the tax benefit shrinks. The optimum point is reached when the marginal present values of the tax benefit and the financial distress cost are equal. The value of the firm is

maximum at this point.

Figure 13.8: Value of levered firm under corporate taxes

PECKING ORDER THEORY

The ‘pecking order’ theory is based on the assertion that managers have more information about their firms than investors. This disparity of information is referred to as asymmetric information. Other things being equal, because of asymmetric information, managers will issue debt when they are positive about their firms’ future prospects and will issue equity when they are unsure. A commitment to pay to fixed amount of interest and principal to debt-holders implies that the company expects steady cash flows. On the other hand, an equity issue would indicate that the current share price is overvalued. Therefore, the manner in which managers raise capital gives a signal of their belief in their firm’s prospects to investors. This also implies that firms always use internal finance when available, and choose debt over new issue of equity when external financing is required. Myers has called it the ‘pecking order’ theory since there is not a well-defined debt-equity target, and there are two kinds of equity, internal and external, one at the top of the pecking order and one at the bottom.12 Debt is cheaper than the costs of internal and external equity due to interest deductibility. Internal equity is cheaper and easier to use than external equity. Internal equity is cheaper because (1) personal taxes might have to be paid by shareholders on distributed earnings while no taxes are paid on retained earnings, and (2) no transaction costs (issue costs, etc.) are incurred when the earnings are retained.13

Managers avoid signalling adverse information about their companies by using internal finance. The profitable firms have lower debt ratios not because they have lower targets but because they have internal funds to finance their activities. They will issue equity capital when they think that shares are overvalued. Because of this, it has been found that the announcement of new issue of shares generally causes share prices of fall. Thus, the pecking order theory implies that managers raise finance in the following order:14

- Managers always prefer to use internal finance.

- When they do not have internal finance, they prefer issuing debt. They first issue secureddebt and then unsecured debt followed by hybrid securities such as convertible debentures. 3. As a last resort, managers issue shares to raise finances.

Check Your Concepts

The pecking order theory is able to explain the negative inverse relationship between profitability and debt ratio within an industry. However, it does not fully explain the capital structure differences between industries.

- What is the interest tax shield? How is it valued?

- What is the value of the levered firm under the MM hypothesis with taxes?

- What is meant by financial distress? What are its costs?

- Briefly explain the essence of the pecking order theory.

CAPITAL STRUCTURE PLANNING AND POLICY

Some companies do not plan their capital structures; it develops as a result of the financial decisions taken by the financial manager without any formal policy and planning. Financing decisions are reactive and they evolve in response to the operating decisions. These companies may prosper in the short-run, but ultimately they may face considerable difficulties in raising funds to finance their activities. With unplanned capital structure, these companies may also fail to economize the use of their funds. Consequently, it is being increasingly realized that a company should plan its capital structure to maximize the use of the funds and to be able to adapt more easily to the changing conditions.

Theoretically, the financial manager should plan an optimum capital structure for the company. The optimum capital structure is one that maximizes the market value of the firm. So far our discussion of the optimum capital structure has been theoretical. In practice, the determination of an optimum capital structure is a formidable task, and one has to go beyond the theory. There are significant variations among industries and among companies within an industry, in terms of capital structure. Since a number of factors influence the capital structure decision of a company, the judgment of the person making the capital structure decision plays a crucial part. Two similar companies may have different capital structures if the decision makers differ in their judgment of the significance of various factors. A totally theoretical model perhaps cannot adequately handle all those factors, which affect the capital structure decision in practice. These factors are highly psychological, complex and qualitative and do not always follow accepted theory, since capital markets are not perfect and the decision has to be taken under imperfect knowledge and risk.

Elements of Capital Structure

The Board of Directors or the chief financial officer (CFO) of a company should develop an appropriate or target capital structure, which is most advantageous to the company. This can be done only when all those factors, which are relevant to the company’s capital structure decision, are properly analyzed and balanced. The capital structure should be planned generally, keeping in view the interests of the equity shareholders and the financial requirements of a company. The equity shareholders, being the owners of the company and the providers of risk capital (equity), would be concerned about the ways of financing a company’s operations. However, the interests of other groups, such as employees, customers, creditors, society and government, should also be given reasonable consideration. As stated in Chapter 1, when the company lays down its objective in terms of the Shareholder Wealth Maximization (SWM), it is generally compatible with the interests of other groups. Thus, while developing an appropriate capital structure for its company, the financial manager should inter alia aim at maximizing the long-term market price per share. Theoretically, there may be a precise point or range within which the market value per share is maximum. In practice, for most companies within an industry there may be a range of an appropriate capital structure within which there would not be great differences in the market value per share. One way to get an idea of this range is to observe the capital structure patterns of companies vis-à-vis their market prices of shares. It may be found empirically that there are not significant differences in the share values within a given range. The management of a company may fix its capital structure near the top of this range in order to make maximum use of favourable leverage, subject to other requirements such as flexibility, solvency, control and norms set by the financial institutions, the Security Exchange Board of India (SEBI) and stock exchanges.

A company formulating its long-term financial policy should, first of all, analyse its current financial structure. The following are the important elements of the company’s financial structure that need proper scrutiny and analysis:15

Capital Mix

Firms have to decide about the mix of debt and equity capital. Debt capital can be mobilized from a variety of sources. How heavily does the company depend on debt? What is the mix of debt instruments? Given the company’s risks, is the reliance on the level and instruments of debt reasonable? Does the firm’s debt policy allow its flexibility to undertake strategic investments in adverse financial conditions? The firms and analysts use debt ratios, debtservice coverage ratios, and the funds flow statement to analyse the capital mix.

Maturity and Priority

The maturity of securities used in the capital mix may differ. Equity is the most permanent capital. Within debt, commercial paper has the shortest maturity and public debt has the longest. Similarly, the priorities of securities also differ. Capitalized debt like lease or hire– purchase finance is quite safe from the lender’s point of view and the value of assets backing the debt provides the protection to the lender. Collateralized or secured debts are relatively safe and have priority over unsecured debt in the event of insolvency. Do maturities of the firm’s assets and liabilities match? If not, what trade-off is the firm making? A firm may obtain a risk-neutral position by matching the maturity of assets and liabilities; that is, it may use current liabilities to finance current assets and short-medium and long-term debt for financing the fixed assets in that order of maturities. In practice, firms do not perfectly match the sources and uses of funds. They may show preference for retained earnings. Within debt, they may use long-term funds to finance current assets and assets with shorter life. Some firms are more aggressive, and they use short-term funds to finance long-term assets.

Terms and Conditions

Firms have choices with regard to the basis of interest payments. They may obtain loans either at fixed or floating rates of interest. In case of equity, the firm may like to return income either in the form of large dividends or large capital gains. What is the firm’s preference with regard to the basis of payments of interest and dividend? How do the firm’s interest and dividend payments match with its earnings and operating cash flows? The firm’s choice of the basis of payments indicates the management’s assessment about the future interest rates and the firm’s earnings. Does the firm have protection against interest rates fluctuations? There are other important terms and conditions that the firm should consider. Most loan agreements include what the firm can do and what it can’t do. They may also state the schemes of payments, pre-payments, renegotiations, etc. What are the lending criteria used by the suppliers of capital? How do negative and positive conditions affect the operations of the firm? Do they constraint and compromise the firm’s operating strategy? Do they limit or enhance the firm’s competitive position? Is the company level to comply with the terms and conditions in good time and bad time?

Currency

Financial Innovations

Firms in a number of countries have the choice of raising funds from the overseas markets. Overseas financial markets provide opportunities to raise large amounts of funds. Accessing capital internationally also helps company to globalize its operations fast. Because international financial markets may not be perfect and may not be fully integrated, firms may be able to issue capital overseas at lower costs than in the domestic markets. The exchange rates fluctuations can create risk for the firm in servicing it foreign debt and equity. The financial manager will have to ensure a system of risk hedging. Does the firm borrow from the overseas markets? At what terms and conditions? How has firm benefited—operationally and/or financially—in raising funds overseas? Is there a consistency between the firm’s foreign currency obligations and operating inflows?

Firms may raise capital either through the issues of simple securities or through the issues of innovative securities. Financial innovations are intended to make the security issue attractive to investors and reduce cost of capital. For example, a company may issue convertible debentures at a lower interest rate rather than non-convertible debentures at a relatively higher interest rate. A further innovation could be that the company may offer higher simple interest rate on debentures and offer to convert interest amount into equity. The company will be able to conserve cash outflows. A firm can issue varieties of optionlinked securities; it can also issue tailor-made securities to large suppliers of capital. The financial manager will have to continuously design innovative securities to be able to reduce the cost. An innovation introduced once does not attract investors any more. What is the firm’s history in terms of issuing innovative securities? What were the motivations in issuing innovative securities and did the company achieve intended benefits?

Financial Market Segments

There are several segments of financial markets from where the firm can tap capital. For example, a firm can tap the private or the public debt market for raising long-term debt. The firm can raise short-term debt either from banks or by issuing commercial papers or certificate deposits in the money market. The firm also has the alternative of raising short-term funds by public deposits. What segments of financial markets have the firm tapped for raising funds and why? How did the firm tap and approach these segments?

Framework for Capital Structure: The FRICT Analysis

A financial structure may be evaluated from various perspectives. From the owners’ point of view, return, risk and value are important considerations. From the strategic point of view, flexibility is an important concern. Issues of control, flexibility and feasibility assume great significance. A sound capital structure will be achieved by balancing all these considerations:

Flexibility The capital structure should be determined within the debt capacity of the company, and this capacity should not be exceeded. The debt capacity of a company depends on its ability to generate future cash flows. It should have enough cash to pay creditors’ fixed charges and principal sum and leave some excess cash to meet future contingency. The capital structure should be flexible. It should be possible for a company to adapt its capital structure with a minimum cost and delay if warranted by a changed situation. It should also be possible for the company to provide funds whenever needed to finance its profitable activities.

Risk The risk depends on the variability in the firm’s operations. It may be caused by the macroeconomic factors and industry and firm specific factors. The excessive use of debt magnifies the variability of shareholders’ earnings, and threatens the solvency of the company.

Control The capital structure should involve minimum risk of loss of control of the company. The owners of closely held companies are particularly concerned about dilution of control. Timing The capital structure should be feasible to implement given the current and future conditions of the capital market. The sequencing of sources of financing is important. The current decision influences the future options of raising capital.

Income The capital structure of the company should be most advantageous to the owners (shareholders) of the firm. It should create value; subject to other considerations, it should generate maximum returns to the shareholders with minimum additional cost.

The FRICT (flexibility, risk, income, control and timing) analysis provides the general framework for evaluating a firm’s capital structure.16 The particular characteristics of a company may reflect some additional specific features. Further, the emphasis given to each of these features will differ from company to company. For example, a company may give more importance to flexibility than control, while another company may be more concerned about solvency than any other requirement. Furthermore, the relative importance of these requirements may change with shifting conditions. The company’s capital structure should, therefore, be easily adaptable.

Check Your Concepts

- What is a target capital structure? How is it different from the optimum capital structure?

- What are the elements of the capital structure that need proper scrutiny and analysis?

- Explain the FRICT approach to the capital structure analysis.

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN DETERMINING CAPITAL STRUCTURE

The determination of capital structure in practice involves additional considerations in addition to the concerns about EPS, value and cash flow. A firm may have enough debt servicing ability but it may not have assets to offer as collateral. Attitudes of firms with regard to financing decisions may also be quite often influenced by their desire of not losing control, maintaining operating flexibility and have convenient timing and cheaper means of raising funds. Some of the most important considerations are discussed below.

Assets

The forms of assets held by a company are important determinants of its capital structure. Tangible fixed assets serve as collateral to debt. In the event of financial distress, the lenders can access these assets and liquidate them to realize funds lent by them. Companies with higher tangible fixed assets will have less expected costs of financial distress and hence, higher debt ratios. On the other hand, those companies, whose primary assets are intangible assets, will not have much to offer by way of collateral and will have higher costs of financial distress. Companies have intangible assets in the form of human capital, relations with stakeholders, brands, reputation, etc., and their values start eroding as the firm faces financial difficulties and its financial risk increases.

Growth Opportunities

Mature firms with low market-to-book value ratio and limited growth opportunities face the risk of managers spending free cash flow either in unprofitable maturing business or diversifying into risky businesses. Both these decisions are undesirable. This behaviour of managers can be controlled by high leverage that makes them more careful in utilizing surplus cash. Mature firms have tangible assets and stable profits. They have low costs of financial distress. Hence these firms would raise debt with longer maturities as the interest rates will not be high for them and they have a lesser need of financial flexibility since their fortunes are not expected to shift suddenly. They can avail high interest tax shields by having high leverage ratios.

The nature of growth opportunities has an important influence on a firm’s financial leverage. Firms with high market-to-book value ratios have high growth opportuni-ties. A substantial part of the value for these companies comes from organizational or intangible assets. These firms have a lot of investment opportunities. There is also higher threat of bankruptcy and high costs of financial distress associated with high growth firms once they start facing financial problems. These firms employ lower debt ratios to avoid the problem of under-investment and costs of financial distress. But bankruptcy is not the only time when debt-financed high-growth firms let go of the valuable investment opportunities. When faced with the possibility of interest default, managers tend to be risk averse and either put off major capital projects or cut down on R&D expenses or both. Therefore, firms with growth opportunities will probably find debt financing quite expensive in terms of high interest to be paid due to lack of good collateral and investment opportunities to be lost. High growth firms would prefer to take debts with lower maturities to keep interest rates down and to retain the financial flexibility since their performance can change unexpectedly any time. They would also prefer unsecured debt to have operating flexibility.

Debt and Non-debt Tax Shields

We know that debt, due to interest deductibility, reduces the tax liability and increases the firm’s after-tax free cash flows. In the absence of personal taxes, the interest tax shields increase the value of the firm. Generally, investors pay taxes on interest income but not on equity income. Hence, personal taxes reduce the tax advantage of debt over equity. The tax advantage of debt implies that firms will employ more debt to reduce tax liabilities and increase value. In practice, this is not always true as is evidenced from many empirical studies. Firms also have non-debt tax shields available to them. For example, firms can use depreciation, carry forward losses, etc., to shield taxes. This implies that those firms that have larger non-debt tax shields would employ low debt, as they may not have sufficient taxable profit available to have the benefit of interest deductibility. However, there is a link between the non-debt tax shields and the debt tax shields since companies with higher depreciation would tend to have higher fixed assets, which serve as collateral against debt.

Financial Flexibility and Operating Strategy

A cash flow analysis might indicate that a firm could carry high level of debt without much threat of insolvency. But in practice, the firm may still make conservative use of debt since the future is uncertain and it is difficult to be able to consider all possible scenarios of adversity. It is, therefore, prudent to maintain financial flexibility that enables the firm to adjust to any change in the future events or forecasting error.

As discussed earlier, financial flexibility is a serious consideration in setting up the capital structure policy. Financial flexibility means a company’s ability to adapt its capital structure to the needs of the changing conditions. The company should be able to raise funds, without undue delay and cost, whenever needed, to finance the profitable investments. It should also be in a position to redeem its debt whenever warranted by the future conditions. The financial plan of the company should be flexible enough to change the composition of the capital structure as warranted by the company’s operating strategy and needs. It should also be able to substitute one form of financing for another to economize the use of funds. Flexibility depends on loan covenants, option to early retirement of loans and the financial slack, viz., excess resources at the command of the firm.

Loan Covenants

Financial Slack

Restrictive covenants are commonly included in the long-term loan agreements and debentures. These restrictions curtail the company’s freedom in dealing with the financial matters and put it in an inflexible position. Covenants in loan agreements may include restrictions to distribute cash dividends, to incur capital expenditure, to raise additional external finances or to maintain working capital at a particular level. The types of covenants restricting the firm’s investment, financing and dividend policies vary depending on the source of debt. While private debt contains both affirmative and negative covenants, public debt has a lot of negative covenants and commercial paper does not entail much restrictions. Loan covenants may look quite reasonable from the lenders’ point of view as they are meant to protect their interests, but they reduce the flexibility of the borrowing company to operate freely and it may become burdensome if conditions change. Growth firms prefer to take private rather than public debt since it is much easier to renegotiate terms in time of crisis with few private lenders than several debenture-holders. Generally, a company while issuing debentures or accepting other forms of debt should ensure to have minimum of restrictive clauses that circumscribe its financial actions in the future in debt agreements. This is a tough task for the financial manager. A highly levered firm is subject to many constraints under debt covenants that restrict its choice of decisions, policies and programmes. Violation of covenants can have serious adverse consequences. The firm’s ability to respond quickly to changing conditions also reduces. The operating inflexibility could prove to be very costly for the firms that are operating in unstable environment. These companies are likely to have low debt ratios and maintain high financial flexibility to remain competitive and not allow compromising their competitive posture. Thus, financial flexibility is essential to maintain the operating flexibility and face unanticipated contingencies.

The financial flexibility of a firm depends on the financial slack it maintains. The financial slack includes unused debt capacity, excess liquid assets, unutilized lines of credit and access to various untapped sources of funds. The financial flexibility depends a lot on the company’s debt capacity and unused debt capacity. The higher is the debt capacity of a firm and the higher is the unused debt capacity, the higher will be the degree of flexibility enjoyed by the firm. If a company borrows to the limit of its debt capacity, it will not be in a position to borrow additional funds to finance unforeseen and unpredictable demands, except at restrictive and unfavourable terms. Therefore, a company should not borrow to the limit of its capacity, but keep available some unused capacity to raise funds in the future to meet some sudden demand for finances.17

Early Repayment

A considerable degree of flexibility will be introduced if a company has the discretion of repaying its debt early. This will enable management to retire or replace cheaper source of finance for the expensive one is whenever warranted by the circumstances. When a company has excess cash and does not have profitable investment opportunities, it becomes desirable to retire debt. Similarly, a company can take advantage of declining rates of interest if it has a right to repay debt at its option. Suppose that funds are available at 12 per cent rate of interest presently. The company has outstanding debt at 16 per cent rate of interest. It can save in terms of interest cost if it can retire the ‘old’ debt and replace it by the ‘new’ debt.

Limits of Financial Flexibility

Sustainability and Feasibility

Financial flexibility is useful, but the firm must understand its limit. It can help a profitable firm to seize opportunities, and it can provide temporary help in adverse situation, but it cannot save a firm, which is basically unhealthy. No doubt that financial flexibility is desirable, but the firm should have basic financial strength. Also, it is achieved at a cost. A company trying to obtain loans on easy terms will have to pay interest at a higher rate. Also, to obtain the right of refunding, it may have to compensate lenders by paying a higher interest or may have to allow them to participate in the equity. Therefore, the company should compare the benefits and costs of attaining the desired degree of flexibility and balance them properly.

The financing policy of a firm should be sustainable and feasible in the long run. Most firms want to maintain the sustainability of their financing policy over a long period of time. The sustainable growth model helps to analyze the sustainability and the feasibility of the longterm financial plans in achieving growth. This model is based on the assumption that the firm uses the internal financing and debt, consistent with the target debt–equity ratio and payout ratio and does not issue shares during the planning horizon. Given the firm’s financing and payout policies and operating efficiency, this model implies that its assets and sales will grow in tandem with growth in equity (internal). Thus, the sustainable growth depends on return on equity (ROE) and retention ratio:

Sustainable growth = ROE × (1 – payout) (20)

ROE depends on assets turnover, net margin, and financial leverage:

ROE = asset turnover × net margin × leverage

ROE = assets/sales × net profit/sales × assets/equity (21)

Alternatively, ROE depends on the firm’s before-tax return on capital employed (ROCE), the financial leverage premium and the tax rate:

ROE = [ROCE + (ROCE – kd) D/E](1 – T) (22)

The sustainable growth model indicates the growth rate that the firm should target. Any other growth rate will not be consistent with the financial policies set by the management. If the firm intends to achieve a different growth rate than that implied by the sustainable growth model, it will have to change its financial policy, either the debt–equity ratio, or the payout ratio or both. In fact, the model also indicates the trade-offs between the financing and operating policies. Instead of changing its financial policies for achieving higher growth, the firm can examine its operating policies vis-à-vis price, cost, assets utilization, etc. The firm must realize that growth does not ensure value creation. If the firm does not account for the investment duration and the cost of capital, growth may destroy value. The firm should also examine the impact of alternative financial policy on the value of the firm.

Control

In designing the capital structure, sometimes the existing management is governed by its desire to continue control over the company. This is particularly so in the case of the firms promoted by entrepreneurs. The existing management team not only wants control and ownership but also to manage the company, without any outside interference.

Widely held Companies

The ordinary shareholders elect the directors of the company. If the company issues new shares, there is risk of dilution of control. The company can issue rights shares to avoid dilution of ownership. But the existing shareholders may not be willing to fully subscribe to the issue. Dilution is not a very important consideration in the case of widely held companies. Most shareholders are not interested in taking active part in a company’s management. Nor do they have time and money to attend the meetings. They are interested in dividends and capital gains. If they are not satisfied, they will sell their shares. Thus, the best way to ensure control and to have the confidence of the shareholders is to manage the company most efficiently and compensate shareholders in the form of dividends and capital gains. The risk of loss of control can be reduced by distribution of shares widely and in small lots.

The consideration of maintaining control may be significant in case of closely held and small companies. A shareholder or a group of shareholders can purchase all or most of the new shares of a small or closely held company and control it. Even if the owner-managers hold the majority shares, their freedom to manage the company will be curtailed when they go for initial public offerings (IPOs). Fear of sharing control and being interfered by others often delays the decision of the closely held small companies to go public. To avoid the risk of loss of control, small companies may slow their rate of growth or issue preference shares or raise debt capital. If the closely held companies can ensure a wide distribution of shares, they need not worry about the loss of control so much.

Closely held Companies

The holders of debt do not have voting rights. Therefore, it is suggested that a company should use debt to avoid the loss of control. However, when a company uses large amount of debt, a lot of restrictions are put by the debt-holders, specifically the financial institutions in India, since they are the major providers of loan capital to the companies. These restrictions curtail the freedom of the management to run the business. A very excessive amount of debt can also cause serious liquidity problem and ultimately render the company sick, which means a complete loss of control.

Marketability and Timing