Key roles and responsibilities of the financial manager

The financial manager is responsible for making decisions which will increase the wealth of the company’s shareholders.

The specific areas of responsibility are listed below.

However, it is also important that the financial manager considers the impact of his role on the other stakeholders of the firm.

You may be asked in the exam to assess the

- strategic impact

- financial impact

- regulatory impact

- ethical impact

- environmental impact of a financial manager’s decisions

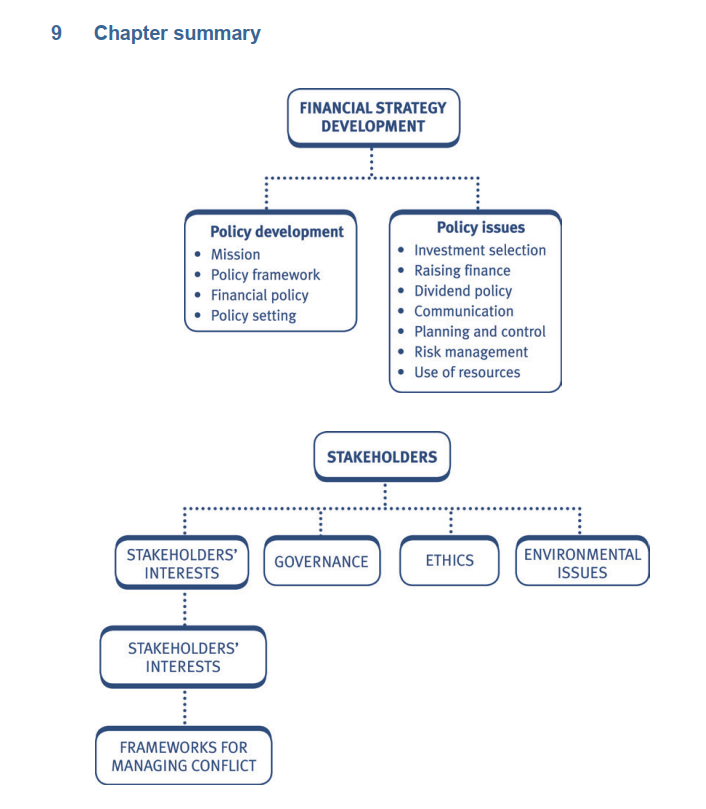

Link between strategy and financial manager’s role

You will remember from your earlier studies that the process of strategy selection starts with the development of a mission statement. A mission statement:

- is the overriding purpose of the firm

- guides and directs all decisions taken.

The mission is then broken down into broad-based goals, and then further, into detailed objectives. Strategies can then be developed to bridge the gap between current forecast performance and the targets set.

Policy framework

The mission will also provide the basis for the development of a policy framework.

The purpose of this framework is:

- to govern the way in which decisions are taken, and

- specify the criteria to be considered in the evaluation of any potential strategy.

At a broad level, this framework will incorporate guidance on issues such as:

Ethics and social responsibility

A consideration of the role of business in society. It covers responsibilities towards society as a whole, the extent to which the company should fulfil or exceed its legal obligations towards stakeholders and the behaviour expected of individuals within the firm itself.

Stakeholder protection

The extent to which the needs and wishes of individual stakeholders are incorporated into decisions and the development of a framework to ensure their needs are met and their rights upheld.

Corporate governance

The system by which companies are directed and controlled, including issues of risk management.

Sustainable development

Ensuring that projects and developments that meet the needs of the present, do not compromise the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

This guidance is often formulated as a general principle:

e.g. all suppliers used must demonstrate commitment to employee welfare,

but may also form the basis for the generation of specific targets:

e.g. increase by 10% the amount of raw materials sourced locally in the next 12 months.

Financial policy

Policies will also be developed to govern decisions within each operational area of the business. These policies specify generally applicable processes or procedures to be followed when decisions are being made, or state one overarching principle which the sets the boundaries for all decisions taken.

The role and responsibility of the financial manager

For example, within the finance function, policies will be developed over areas such as:

- investment selection

- overall cost of finance

- distribution and retentions

- communication with stakeholders

- financial planning and control

- risk management

- efficient and effective use of resources.

Key areas of responsibility for the financial manager

The main roles and responsibilities of the financial manager can be summarised by the following headings:

- investment selection and capital resource allocation

- raising finance and minimising the cost of capital

- distribution and retentions (dividend policy)

- communication with stakeholders

- financial planning and control

- risk management

- efficient and effective use of resources.

The Advanced Financial Management syllabus (and the rest of this Text) covers these areas in detail. This chapter gives a brief introduction to each of them.

Investment selection and capital resource allocation

The primary goal of a company should be the maximisation of shareholder wealth, but any number of stakeholders may have views on the objectives a company should pursue.

Therefore, key policy decisions need to be made:

What method of investment appraisal should be used?

– NPV?

– IRR?

In times of capital rationing, how are competing projects to be evaluated?

– use of theoretical methods

– incorporation of non-financial factors such as:

(1) closeness of match to objectives

(2) degree to which all goals will be achieved.

• As markets are not truly efficient, and investors treat earnings and

dividend announcements as new information, to what extent should the

impact on, for example:

– ROCE

– EPS

– DPS

be considered when evaluating a project?

| More on investment selection |

| Incorporation of corporate policy issues If for example, a decision has been taken to pay a ‘fair’ wage to all employees regardless of the legal minimum requirement in the country where the business is operating, this rule must be applied to the wages figure used in any project evaluation. The financial executive must be aware of the policy requirement and ensure that sufficient research is carried out in advance that the correct figure is used. Methods of investment appraisal Assuming that the discounted cash flow techniques are preferred over Payback and ARR (which do not assure the maximisation of shareholder wealth), it is still necessary to designate which of the DCF methods is to be applied. Although NPV is theoretically superior, it is not as well liked by non-financial managers. IRR as a percentage is deemed clearer and simpler (although the point could be argued!). It is for the senior financial executive to decide on a method and ensure it is applied correctly. Capital rationing The rule for an NPV evaluation states that all projects with a positive NPV should be accepted. However, this presupposes no limits on the available funds. Where restrictions exist, theoretical models can be applied: • Shortages in one period only – use limiting factor analysis (covered in the Financial Management exam). • Shortages in multiple periods – see Chapter 2: Investment appraisal |

However, these methods do not build in evaluation of non-financial

factors such as how well each strategy will meet the objectives set and

practical difficulties that might be encountered along the way.

Forms of evaluation such as Cost Benefit Analysis and Weighted Benefit

Scoring can be used where these factors are significant. These methods,

pioneered by the public sector where such problems are commonplace,

include techniques to assign money values to non-financial factors and to

weight subjective factors against each other. Detailed knowledge of such

methods is outside the syllabus.

Earning and dividend measures

Even where improving shareholder wealth is the primary concern of the

financial executive, the impact of the investment decisions on the

reported position and perceived performance of the firm cannot be

ignored. In an imperfect market, the earnings of a company and the

dividends paid, are treated as relevant information for evaluating a

company’s worth and may impact the share price. Yet it is the share price

that the executive is trying to improve.

| Behavioural finance |

| Introduction Conventional financial management is based on the assumption that markets are efficient, and that investors behave in ways that are logical and rational. The efficient market hypothesis (EMH) The EMH states that security prices fully and fairly reflect all relevant information. This means that it is not possible to consistently outperform the market by using any information that the market already knows, except through luck. The idea is that new information is quickly and efficiently incorporated into asset prices at any point in time, so that old information cannot be used to predict future price movements. Behavioural finance Despite the evidence in support of the efficient markets theory, some events seem to contradict it, such as significant share price volatility and boom/crash patterns e.g. the stock market crash of October 1987 where most stock exchanges crashed at the same time. It is virtually impossible to explain the scale of those market falls by reference to any news event at the time |

An explanation has been offered by the science of behavioural finance.

Behavioural finance is a relatively new field that seeks to combine

behavioural and cognitive psychological theory with conventional

economics and finance to provide explanations for why people make

irrational financial decisions.

Key concepts of behavioural finance

Pioneers in the field of behavioural finance have identified the following

factors as some of the key factors that contribute to irrational and

potentially detrimental financial decision making:

Anchoring – investors have a tendency to attach or ‘anchor’ their

thoughts to a reference point – even though it may have no logical

relevance to the decision at hand e.g. investors are often attracted to buy

shares whose price has fallen considerably because they compare the

current price to the previous high (but now irrelevant) price.

Gambler’s fallacy – investors have a tendency to believe that the

probability of a future outcome changes because of the occurrence of

various past outcomes e.g. if the value of a share has risen for seven

consecutive days, some investors might sell the shares, believing that the

share price is more likely to fall on the next day. This is not necessarily

the case.

Herd behaviour– this is the tendency for individuals to mimic the actions

(rational or irrational) of a larger group. There are a couple of reasons

why herd behaviour happens. The first is the social pressure of

conformity – most people are very sociable and have a natural desire to

be accepted by a group. The second is the common rationale that it’s

unlikely that such a large group could be wrong. This is especially

prevalent in situations in which an individual has very little experience.

Over-reaction and availability bias – according to the EMH, new

information should more or less be reflected instantly in a security’s price.

For example, good news should raise a business’ share price

accordingly. Reality, however, tends to contradict this theory. Often,

participants in the stock market predictably over-react to new information,

creating a larger-than-appropriate effect on a security’s price.

Confirmation bias – it can be difficult to encounter something or

someone without having a preconceived opinion. This first impression

can be hard to shake because people also tend to selectively filter and

pay more attention to information that supports their opinions, while

ignoring or rationalising the rest. This type of selective thinking is often

referred to as the confirmation bias.

In investing, the confirmation bias suggests that an investor would be

more likely to look for information that supports his or her original idea

about an investment rather than seek out information that contradicts it.

As a result, this bias can often result in faulty decision making because

one-sided information tends to skew an investor’s frame of reference,

leaving them with an incomplete picture of the situation

Hindsight bias and overconfidence – hindsight bias occurs in

situations where a person believes (after the fact) that the onset of some

past event was predictable and completely obvious, whereas in fact, the

event could not have been reasonably predicted.

Many events seem obvious in hindsight. For example, many people now

claim that signs of the technology bubble of the late 1990s and early

2000s were very obvious. This is a clear example of hindsight bias: If the

formation of a bubble had been obvious at the time, it probably wouldn’t

have escalated and eventually burst.

For investors and other participants in the financial world, the hindsight

bias is a cause for one of the most potentially dangerous mind-sets that

an investor or trader can have: overconfidence. In this case,

overconfidence refers to investors’ or traders’ unfounded belief that they

possess superior stock-picking abilities.

Student Accountant article

The article ‘Patterns of behaviour’ in the Technical Articles section of the

ACCA website provides further details on behavioural finance.

Raising finance and minimising the cost of capital

A key aspect of financial management is the raising of funds to finance existing

and new investments. As with investment decisions, the main objective with

raising finance is assumed to be the maximisation of shareholder wealth.

The following issues thus need to be considered when setting criteria for future

finance and deciding policies:

• Is the firm at its optimal gearing level with associated minimum cost of

capital?

• What gearing level is required?

• What sources of finance are available?

• Tax implications.

• The risk profile of investors and management.

• Restrictions such as debt covenants.

• Implications for key ratios.

Distribution and retention (dividend) policy

When deciding how much cash to distribute to shareholders, the company

directors must keep in mind that the firm’s objective is to maximise shareholder

value:

• Shareholder value arises from the current value of the shares which in turn

is derived from the cash flows from investment decisions taken by the

company’s management.

Retained earnings are a significant source of finance for companies and

therefore directors need to ensure that a balance is struck:

– Paying out too much may require alternative finance to be found to

finance any capital expenditure or working capital requirements.

– Paying out too little may fail to give shareholders their required

income levels.

• The dividend payout policy, therefore, should be based on investor

preferences for cash dividends now or capital gains in future from

enhanced share value resultant from re-investment into projects with a

positive NPV.

It is the task of the financial manager to decide on the appropriate policy for

determining distributions and retentions.

Communication with stakeholders

A vital role for those running a company is to keep both external and internal

stakeholders informed of all significant matters.

External stakeholders

External stakeholders to be kept informed would include:

• shareholders

• government

• suppliers

• customers

• community at large.

Internal stakeholders

Corporate goals and financial policies must be communicated to all those

involved within the organisation, whether at a senior level or in operational

positions

• managers/directors

• employees.

| Test your understanding 1 |

| Suggest reasons why it would be important to keep each of the above stakeholders informed of general corporate goals and intentions |

In addition to information about corporate goals, key matters of financial policy

will also need to be communicated to stakeholders:

• Shareholders will need information about:

– dividend policy

– expected returns on new investment projects

– gearing levels

– risk profile.

• Suppliers and customers will need information about:

– payment policies

– pricing policies.

Financial planning and control

Financial planning and control is the main role of the management accountant

within a company.

The senior financial executive will need to oversee the development of policies

to govern the way in which the process is carried out.

Policies will be needed over areas such as:

• the planning process

• business plans

• budget setting

• monitoring and correcting activities

• evaluating performance.

The management of risk

One of the key matters to consider when developing a financial policy

framework is the way risk and risk management is to be incorporated into the

decision making process.

A number of policy decisions must be made:

• What is the firm’s appetite for risk?

• How should risk be monitored?

• How should risk be dealt with?

A major part of the AFM syllabus involves the choice and use of many

alternative methods and products to manage risk exposure.

| More detail on risk management |

| Appetite for risk Shareholders will invest in companies with a risk profile that matches that required for their portfolio. Management should be wary of altering the risk profile of the business without shareholder support. An increase in risk will bring about an increase in the required return and may lead to current shareholders selling their shares and so depressing the share price. Inevitably management will have their own attitude to risk. Unlike the well-diversified shareholders, the directors are likely to be heavily dependent on the success of the company for their own financial stability and be more risk averse as a consequence. Monitoring risk The essence of risk is that the returns are uncertain. As time passes, so the various uncertain events on which the forecasts are based will occur. Management must monitor the events as they unfold, reforecast predicted results and take action as necessary. The degree and frequency of the monitoring process will depend on the significance of the risk to the project’s outcome. Dealing with risk Risk can be either accepted or dealt with. Possible solutions for dealing with risk include: • mitigating the risk – reducing it by setting in place control procedures • hedging the risk – taking action to ensure a certain outcome • diversification – reducing the impact of one outcome by having a portfolio of different ongoing projects. Policy decisions about which methods are to be preferred should be made in advance of specific actions being required. |

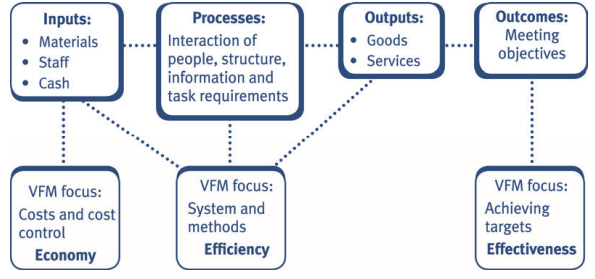

Use of resources

It will be important to develop a framework to ensure all resources (inventory,

labour and non-current assets as well as cash) are used to provide value for

money. Spending must be:

• economic

• efficient

• effective

• transparent.

Performance measures can be developed in each area to set targets and allow

for regular monitoring.

| Definitions of the 3 Es |

| Economy: Minimising the costs of inputs required to achieve a defined level of output. Efficiency: Ratio of outputs to inputs – achieving a high level of output in relation to the resources put in. Effectiveness: Whether outputs are achieved that match the predetermined objectives. Transparency: Ensuring all spending is recorded and reported correctly. |

Treasury

The role of the treasury function

Most large companies have a separate treasury function to undertake some of

the above listed roles.

Developments in technology, the breakdown of exchange controls, increasing

volatility in interest rates and exchange rates, combined with the increasing

globalisation of business have all contributed to greater opportunities and risks

for entities. To survive in today’s complex financial environment, entities need to

be able to actively manage both their ability to undertake these opportunities,

and their exposure to risks.

A separate treasury function is more likely to develop the appropriate skills, and

it should also be easier to achieve economies of scale; for instance in achieving

lower borrowing rates, or netting-off balances.

Treasury and financial control

In a large entity the finance function may be split between treasury and financial

control, with both functions reporting to the chief financial officer.

The financial control function will be concerned primarily with the allocation and

effective use of resources, and will have responsibility for investment decisions.

The treasury function is usually responsible for obtaining finance and managing

relations with the financial stakeholders of the entity who will include

shareholders and lenders.

Close liaison is often required between financial control and treasury, for

example:

• In investment appraisal decisions, the treasurer is best able to assess the

cost of capital and quantify the entity’s aversion to risk, while the financial

controller relates these factors to group strategy.

• When managing currency risks, the financial controller will play an

important role in identifying the entity’s currency risks, while the treasurer

advises on the best means to hedge the risk.

In larger entities, treasury will usually be centralised at head office, providing a

service to all the various units of the entity and thereby achieving more effective

control over financial risks and also achieving economies of scale (for example,

by obtaining better borrowing rates).

Financial control is frequently delegated to individual units, where it can more

closely impact on customers and suppliers and relate more specifically to the

competition that those units have to face.

As a result, treasury and financial control may often tend to be separated by

location as well as by responsibilities.

| Test your understanding 2 |

| Compare and contrast the roles of the treasury and financial control departments with respect to a proposed investment. |

| Treasury: Cost centre or profit centre? |

| As a cost centre the aggregate treasury function costs would simply be charged throughout the group on a fair basis. If no such fair basis can be agreed, the costs can remain as central head office unallocated costs in any group segmental analysis. However it is also possible to identify revenues arising from treasury departments and thus to establish the treasury as a profit centre. Revenues could be realised as follows: • Each division can be charged the market value for the services provided by the treasury. The total value charged throughout the group should exceed the treasury’s costs enabling it to report a profit. • By deciding not to hedge all currency and interest rate risks. Experts in the treasury could decide which risks not to hedge, hoping to profit from unhedged favourable exchange rate and interest rate movements. • Hedging using currency and interest rate options leaves an upside potential which could be realised if the rate moves in the company’s favour. • Taking on additional exchange rate or other risks purely as a speculative activity, e.g. writing options on currencies or on shares held. The trend in recent years has been for large companies to turn their treasuries from cost centres into profit centres and to expect the treasury to pay its way and generate regular profits each year. However the following points should be noted: • A treasury engaged in speculation must be properly controlled by the company’s board of directors. Millions of dollars can be committed in one telephone call by a treasurer, so it is crucial that limits are set on traders’ risk exposures and that these limits are monitored scrupulously. The temptation has been for directors to let treasurers ‘get on with whatever they do’ as long as regular profits are being earned. Such a policy is no longer acceptable; the finance director in particular must control the treasury on a day-to-day basis. |

For example, the German oils and metals company

Metallgesellschaft managed to lose $1 billion after becoming overexposed to oil derivative contracts.

• Treasury staff must be well trained and probably well paid, so that

staff of the right calibre can be secured.

• The low volume of foreign currency transactions undertaken by a

small company would probably make a profit centre approach

unviable. A regular flow of large foreign transactions is needed

before the cost centre approach is abandoned.

| International aspects |

| The international treasury function The corporate treasurer in an international group of companies will be faced with problems relating specifically to the international spread of investments. • Setting transfer prices to reduce the overall tax bill. • Deciding currency exposure policies and procedures. • Transferring of cash across international borders. • Devising investment strategies for short-term funds from the range of international money markets and international marketable securities. • Netting and matching currency obligations. |

| The centralisation of treasury activities |

| The question arises in a large international group of whether treasury activities should be centralised or decentralised. • If centralised, then each operating company holds only the minimum cash balance required for day to day operations, remitting the surplus to the centre for overall management. This process is sometimes known as cash pooling, the pool usually being held in a major financial centre or a tax haven country. • If decentralised, each operating company must appoint an officer responsible for that company’s own treasury operations. Advantages of centralisation • No need for treasury skills to be duplicated throughout the group. One highly trained central department can assemble a highly skilled team, offering skills that could not be available if every company had their own treasury. |

| Agency theory |

| Agency theory identifies that, although individual members of a business team act in their own self-interests much of the time, the well-being of each individual and of the business overall depends on the well-being of the other team members too. The separation of owners and management in many businesses leads to the classic ‘agency problem’. Definition of ‘Agency Problem’ A conflict of interest inherent in any relationship where one party is expected to act in another’s best interests. The problem is that the agent who is supposed to make the decisions that would best serve the principal is naturally motivated by self-interest, and the agent’s own best interests may differ from the principal’s best interests. Application to shareholders/managers In corporate finance, the agency problem usually refers to a conflict of interest between a company’s management and the company’s owners or shareholders. The manager, acting as the agent for the shareholders, or principals, is supposed to make decisions that will maximise shareholder wealth. However, it is in the manager’s own best interest to maximise his own wealth. While it is not possible to eliminate the agency problem completely, the manager can be motivated to act in the shareholders’ best interests through incentives such as performance-based compensation, direct influence by shareholders, the threat of firing and the threat of takeovers. Application to not-for-profit organisations In not-for-profit and public sector organisations, the agency problem changes, because of the ambiguity in identifying the principals, or owners, of the organisation. It could be argued that the owner of a public sector organisation such as a hospital is society as a whole, so there is more a moral rather than a legal ownership in place. As with a profit-focussed organisation, the managers have to make decisions in the best interests of the ‘owners’ rather than in their own interests, so the agency problem doesn’t disappear in a not-for-profit organisation. |

| Examples of stakeholder conflict |

| Stakeholders Potential conflict Costs resulting from the conflict Employees v Shareholders Employees may resist the introduction of automated processes which would improve efficiency but cost jobs. Shareholders may resist wage rises demanded by employees as uneconomical. Costs of strike or work to rule from employees. Costs of additional compensation to redundant staff. Costs of strikes etc. as above. Costs of reassuring shareholders – additional meetings for example. Customers v Community at large Customers may demand lower prices and greater choice, but in order to provide them a company may need to squeeze vulnerable suppliers or import products at great environmental cost. Costs of overcoming negative publicity. Time spent renegotiating supplier contracts/ sourcing new suppliers. Shareholders v Finance providers Shareholders may encourage management to pursue risky strategies in order to maximise potential returns, whereas finance providers prefer stable lower risk policies that ensure liquidity for the payment of debt interest. Agency costs: loan covenants restricting further borrowing, dividend payouts, investment policy etc. Government v Shareholders Government will often insist upon levels of welfare (such as the minimum wage and Health and Safety practices) which would otherwise be avoided as an unnecessary expense. Costs of complying with legislation. NB: You may have come up with different suggestions in an exam scenario. The point is to recognise that there are a huge range of potential conflicts of interest and each one results in additional costs for the business and therefore a reduction in returns to shareholders. |

Strategies for the resolution of stakeholder conflict

Hierarchies of decision making (corporate governance codes)

In order to prevent abuse of decision-making power by the executive, control

over decisions tends to be distributed between:

• the full board

• individual executive directors making operational decisions

• non-executive directors

– audit committee

– remuneration committee

• shareholders in general meeting

• specific classes of shareholders where particular rights are concerned.

In addition, a company may elect to take some key decisions in consultation

with the employees.

| More on Corporate Governance |

| The full board Whilst for most operational matters, decisions may be taken by the appropriate functional director, matters of corporate policy, investment decisions over a certain limit, sensitive decisions etc. are likely to require the consent of the full board. This ensures that all salient factors are considered when the decision is taken. Non-executive directors Whilst executive directors are employees involved in the day-to-day running of the business, non-executives are independent of the company, and appointed to monitor and challenge the executives as well as to advise and support them. Removing decisions such as director remuneration and appointment from the remit of the executive, mitigates the likelihood of directors making self-serving decisions contrary to the interests of other stakeholders. In addition, creating an audit committee to provide an independent reporting line for internal auditors and external auditors alike, provides a safeguard for shareholders against potential cover-ups of poor management practices. |

Shareholders in general meeting

Legislation reserves for the shareholders certain key corporate decisions

such as the appointment and removal of auditors and directors. When

taking decisions, the directors will be aware that ignoring the wishes of

the shareholders would put them at risk of removal. Shareholders may

also use the company general meetings as an opportunity to express

their concerns and remind the directors of their voting control.

Specific classes of share

In order to protect the rights of non-voting shareholders such as those

holding preference shares, it is common to allow them voting rights in

particular circumstances such as where their dividend goes into arrears.

The principles of corporate governance

Corporate governance is usually defined as ‘the system by which

companies are directed and controlled’. The concept encompasses

issues of ethics, risk management and stakeholder protection.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

issues specific guidelines for national legislation and regulation in the

form of the Principles of Corporate Governance. These were explored in

the Strategic Business Leader syllabus.

Practical implications

The implications of the guidelines for companies in all countries are a

need for the:

• Separation of the supervisory function and the management

function.

• Transparency in the recruitment and remuneration of the board.

• Appointment of non-executive directors.

• Establishment of an audit committee.

• Establishment of risk control procedures to monitor strategic,

business and operational activities.

Performance monitoring and evaluation systems

Managers are more likely to act in accordance with shareholders’ wishes when

their performance is regularly monitored and appraised against prescribed

targets. To be of real value, the targets must be congruent with the

maximisation of shareholder value.

| Performance appraisal methods – Link to s/h wealth maximisation |

| Listed below are some of the ways in which management performance may be appraised. For each method we have considered the extent to which it is congruent with the maximisation of shareholder wealth objective. Financial measures Accounting ratios: • EPS/ROCE/RI – both suffer from the same criticism – that earnings are not directly related to shareholder wealth and therefore may encourage non-goal congruent behaviour. • DPS – is a measure of immediate improvement in wealth but must be looked at in conjunction with the company share price. Dividends may be reduced in order to invest in positive NPV projects, but in that case, the gain should be reflected in the share price. • Economic value added – EVA is a more sophisticated method of residual income (registered as a trademark by Stern, Stewart & Co.), which more accurately measures improvements in shareholder wealth by adjusting the accounting data to eliminate much of the subjectivity and incorporating the company’s WACC into the calculation. Stock market figures: • Share price – reflects the expectations of the investors. Is a direct measure of company success but is hard to link directly to directors’ performance as it is affected by so many outside factors. • PE ratio – as a multiple of share price over earnings it does reflect investors’ view of the investment potential of the company but suffers from the same weakness as all other earnings related measures and is not easy to relate to directors activities. Shareholder value added A calculation of the present value free cash flows, this method is a more accurate measure of improvements in shareholder wealth, but its complexity makes it of little use as a regular performance measure. |

Specific cost/revenue targets

A vast array of financial targets may be set around the levels of spending

and investment, or around revenues earned. Care must be taken to

ensure that the targets are achievable and within the control of the

person being assessed. Particular attention must be paid to the

interdependence of the various aspects of performance. If managers are

incentivised to achieve a reduction in purchase spending for example,

alternative measures must also confirm that quality is maintained.

Non-financial measures

Balanced scorecard

Many businesses operate a balanced scorecard approach to

management appraisal. This involves setting targets in all of those

aspects of the business where success is necessary if positive NPVs are

to be earned. In addition to financial targets, managers are measured on

the satisfaction of customers, improvement of business practices and

levels of innovation. Since achieving these targets should lead to

improved project returns and greater cost efficiency, a balanced

scorecard approach should lead to improved shareholder wealth.

Employee/satisfaction

In addition, some businesses specifically set management targets related

to employee satisfaction ratings, or related targets such as absenteeism

or staff turnover.

| Non-financial information |

| According to the International Accounting Standards Board’s (IASB’s) conceptual framework, the objective of financial reporting is to ‘provide information about the reporting entity that is useful to existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors in making decisions about providing resources to the entity’. Financial statements provide historic financial information. To help users make decisions, it may be helpful to provide information relating to other aspects of an entity’s performance. For example: • how the business is managed • its future prospects • the entity’s policy on the environment • its attitude towards social responsibility etc. There has been increasing pressure for entities to provide more information in their annual reports beyond just the financial statements since non-financial information can also be important to users’ decisions. |

Non-financial reporting

The important additional non-financial information can be reported in a

number of ways, for example:

A management commentary (sometimes called an operating and

financial review) will assess the results of the period and discuss future

prospects of the business.

An environmental report will discuss responsibilities towards the

environment and a social report will discuss responsibilities towards

society. Both these issues could be combined in a report on sustainability

which will also encompass economic issues.

| Integrated Reporting |

| The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) The IIRC was formed in 2010 and aims to create a globally accepted framework for a process that results in communications by an organisation about value creation over time. The IIRC brings together a cross section of representatives from corporate, investment, accounting, securities, regulatory, academic and standard-setting sectors as well as civil society. Objective of the IIRC At the time of its formation, the IIRC’s stated objective was to develop an internationally accepted integrated reporting framework to create the foundations for a new reporting model to enable organisations to provide concise communications of how they create value over time. After a consultation process, the IIRC published the first version of its ‘International Integrated Reporting Framework’ in 2013. This framework is intended as a guide for all businesses producing integrated reports. The concept of Integrated Reporting (<IR>) Integrated Reporting (<IR>) is seen by the IIRC as the basis for a fundamental change in the way in which entities are managed and report to stakeholders. A stated aim of <IR> is to support integrated thinking and decision making. Integrated thinking is described in the <IR> Framework as “the active consideration by an organization of the relationships between its various operating and functional units and the capitals that the organization uses or affects” |

The objectives for integrated reporting include:

• To improve the quality of information available to providers of

financial capital to enable a more efficient and productive allocation

of capital.

• Provide a more cohesive and efficient approach to corporate

reporting that draws on different reporting strands and

communicates the full range of factors that materially affect the

ability of an organisation to create value over time.

• Enhance accountability and stewardship for the broad base of

capitals (financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and

relationship, and natural) and promote understanding of their

interdependencies.

• Support integrated thinking, decision-making and actions that focus

on the creation of value over the short, medium and long term.

Purpose and content of an integrated report

The <IR> Framework sets out the purpose of an integrated report as

follows:

The primary purpose of an integrated report is to explain to

providers of financial capital how an entity creates value over time.

An integrated report benefits all stakeholders interested in an

entity’s ability to create value over time, including employees,

customers, suppliers, business partners, local communities,

legislators, regulators, and policy-makers.

The ‘building blocks’ of an integrated report are:

Guiding principles – these underpin the preparation of an integrated

report, informing the content of the report and how information is

presented.

Content elements – the key categories of information required to be

included in an integrated report under the Framework, presented as a

series of questions rather than a prescriptive list of disclosures.

<IR> illustration

Key requirements of an integrated report

An integrated report should be a designated, identifiable communication.

A communication claiming to be an integrated report and referencing the

<IR> Framework should apply all the key requirements (identified using

bold type below), unless the unavailability of reliable data, specific legal

prohibitions or competitive harm results in an inability to disclose

information that is material (in the case of unavailability of reliable data or

specific legal prohibitions, other information is provided).

Performance – To what extent has the organisation achieved its

strategic objectives for the period and what are its outcomes in terms of

effects on the capitals?

Outlook – What challenges and uncertainties is the organisation likely to

encounter in pursuing its strategy, and what are the potential implications

for its business model and future performance?

Basis of preparation and presentation – How does the organisation

determine what matters to include in the integrated report and how are

such matters quantified or evaluated?

Integrated reporting (<IR>) and performance appraisal

<IR> enables an organisation to prepare a much wider range of information that

can be used by stakeholders to appraise the performance of the management.

The <IR> information covers both financial and non-financial performance.

Therefore, when making decisions, the financial manager must consider the

impact of the decisions on all aspects of the organisation’s performance, not

just its financial performance.

Student Accountant article

Read the article ‘Myopic management’ in the Technical Articles section of the

ACCA website for more details on stakeholder considerations and finding a

balance between short-term and long-term success of a business.

4 The strategic impact of the financial manager’s decisions

Strategic issues are those which impact the whole business in the long term.

Key strategic issues which may arise from decisions made by the financial

manager are:

Does the new investment project help to enhance the firm’s competitive

advantage?

For example, if the firm has traditionally competed on the basis of cost

leadership, the financial manager needs to ensure that new projects maintain

this position, and that any new finance is raised at the lowest possible cost.

Fit with environment

A knowledge of the main Political, Economic, Social and Technological factors

which impact the business will help the financial manager to identify likely

opportunities.

Use of resources

The financial manager should identify new investment opportunities which make

the best use of the firm’s key resources. Knowledge of the firm’s current

strengths (core competencies) and weaknesses is critical in assessing which

new projects are most likely to be successful.

Stakeholder reactions

As discussed above, it is critical that the views of all stakeholders are

considered when financial management decisions are made. Theoretically, the

directors have a primary objective to maximise shareholder wealth. However,

decisions which appear to satisfy this requirement by ignoring other

stakeholders’ views in the short term can damage the firm’s prospects for longer

term shareholder wealth maximisation.

Impact on risk

Investors will have been attracted to the firm because they deem its risk profile

to be acceptable. Making decisions which change the overall risk of the firm

may alienate shareholders and damage the firm’s long term prospects.

5 The financial impact of the financial manager’s decisions

It is common to assess the financial impact of a financial manager’s decision by

focussing on the likely Net Present Value (NPV) of investment projects

undertaken. After all, the primary aim of a company is to maximise the wealth of

its shareholders, and NPV represents the increase in shareholder wealth if a

project is undertaken.

However, it is also important to consider the following issues:

Likely impact on share price

In a perfect capital market, the NPV of the project would immediately be

reflected in the company’s share price. In the real world, unless the details of

the project are communicated effectively to the market, the share price will not

be impacted.

Likely impact on financial statements

In theory, a positive NPV project should increase shareholder wealth. However,

if the project has low (or negative) cash flows in the early years, the negative

impact on the financial statements in the short term may give a negative signal

to the market, thus causing the share price to fall.

Impact on cost of capital

As discussed in detail elsewhere, raising new finance causes the firm’s cost of

capital to change. However, undertaking projects of different business risk from

the firm’s existing activities can also impact cost of capital. Projects will be more

valuable when discounted at a low cost of capital, so the financial manager

should avoid high risk projects unless it is felt that they are likely to deliver a

high level of return.

| Test your understanding 3 |

| The directors of Ribs Co, a listed company, are reviewing the company’s current strategic position. The firm makes high quality garden tools which it sells in its domestic market but not abroad. Over the last few years, the share price has risen significantly as the firm has expanded organically within its domestic market. Unfortunately, in the last 12 months, the influx of cheaper, foreign tools has adversely impacted the firm’s profitability. Consequently, the share price has dropped sharply in recent weeks and the shareholders expressed their displeasure at the recent AGM. The directors are evaluating two alternative investment projects which they hope will arrest the decline in profitability. Project 1: This would involve closing the firm’s domestic factory and switching production to a foreign country where labour rates are a quarter of those in the domestic market. Sales would continue to be targeted exclusively at the domestic market. Project 2: This would involve a new investment in machinery at the domestic factory to allow production to be increased by 50%. The extra tools would be exported and sold as high quality tools in foreign market places. Both projects have a positive Net Present Value (NPV) when discounted at the firm’s current cost of capital. Required: Discuss the strategic and financial issues that this case presents. |

6 The regulatory impact of the financial manager’s decisions

The extent to which the financial manager’s actions are scrutinised by

regulators is determined by:

• the type of industry – some industries (for example the privatised utility

industries in the UK) are subject to high levels of regulation

• whether the company is listed – listed companies are subject to high levels

of scrutiny. The Regulator for Public Companies has the primary objective

of ensuring clarity for all investors.

The UK City Code

The City Code applies to takeovers in the UK. It stresses the vital importance of

absolute secrecy before any takeover announcement is made. Once an

announcement is made, the Code stipulates that the announcement should be

as clear as possible, so that all shareholders (and potential shareholders) have

equal access to information.

The ethical impact of the financial manager’s decisions

Ethics, and the company’s ethical framework, should provide a basis for all

policy and decision making. The financial manager must consider whether an

action is ethical at a:

• society level

• corporate level

• individual level.

| Explanation of levels of ethics |

| Society level The extent to which the wishes of all stakeholders both internal and external should be taken into account, even where there is no legal obligation to do so. Corporate level The extent to which companies should exceed legal obligations to stakeholders, and the approach they take to corporate governance and stakeholder conflict. Individual level The principles that the individuals running the company apply to their own actions and behaviours. |

As key members of the decision-making executive, financial managers are

responsible for ensuring that all the actions of the company for which they work:

• are ethical

• are grounded in good governance

• achieve the highest standards of probity.

In addition to general rules of ethics and governance, members of the ACCA

have additional guidance to support their decision making.

| ACCA Code of Ethics |

| At an individual level, members of the ACCA are governed by a set of fundamental ethical principles. These principles are binding on all members and members review and agree to them each year when they renew their ACCA membership and submit their CPD return. The fundamental principles are: • integrity • objectivity • professional competence and due care • confidentiality • professional behaviour. Integrity Members should be straightforward and honest in all professional and business relationships. Objectivity Members should not allow bias, conflicts of interest or undue influence of others to override professional or business judgements. Professional competence and due care Members have a continuing duty to maintain professional knowledge and skill at a level required to ensure that a client or employer receives competent professional service based on current developments in practice, legislation and techniques. Members should act diligently and in accordance with applicable technical and professional standards when providing professional services. Confidentiality Members should respect the confidentiality of information acquired as a result of professional and business relationships and should not disclose any such information to third parties without proper and specific authority or unless there is a legal or professional right or duty to disclose. Confidential information acquired as a result of professional and business relationships should not be used for the personal advantage of members or third parties. Professional behaviour Members should comply with relevant laws and regulations and should avoid any action that discredits the profession. |

In working life, a financial manager may:

• have to deal with a conflict between stakeholders

• face a conflict between their position as agent and the needs of the

shareholders for whom they act.

An ethical framework should provide a strategy for dealing with the situation.

| More on ethics |

| Ethical financial policy All senior financial staff would be expected to sign up and adhere to an ethical financial policy framework. A typical code would cover matters such: • acting in accordance with the ACCA principles • disclosure of any possible conflicts of interest at the first possible opportunity to the appropriate company member • ensuring full, fair, accurate, complete, objective, timely and understandable disclosure in all reports and documents that the company files • ensuring all company financial practices concerning accounting, internal accounting controls and auditing matters meet the highest standards of professionalism, transparency and honesty • complying with all internal policy all external rules and regulations • responsible use and control of assets and other resources employed • promotion of ethical behaviour among subordinates and peers and ensuring an atmosphere of continuing education and exchange of best practices. Assessing the ethical impact of decisions Once a framework has been developed it is essential that all decisions are made in accordance with it. This will involve: • all employees explicitly signing up to the framework • providing employees with guidelines to apply to ethical decisions • offering resources for consultation in ethical dilemma • ensuring unethical conduct can be reported without reprisal • taking disciplinary action where violations have occurred. |

Guidelines for making ethical decisions often take the form of a series of

questions which employees are encouraged to ask themselves before

implementing a decision.

For example:

• Have colleagues been properly consulted?

• Are actions legal and in compliance with professional standards?

• Is individual or company integrity being compromised?

• Are company values being upheld?

• Is the choice of action the most ethical one?

• If the decision were documented would a reviewer agree with the

decision taken?

In addition to written ethical guidelines firms often provide employees with

a list of people who can be consulted in the case of an ethical dilemma.

For example:

• Line manager.

• Appointed quality and risk leaders.

• Firm legal team.

• Ethics hotline within the firm (obviously only in larger companies is

this likely to be affordable).

• Professional hotline – the ACCA for example, provides its members

with ethical advice and support, as do many other professional

organisations.

Interconnectedness of the ethics of good business practice

The ethical financial manager understands the importance of the

interconnectedness of the ethics of good business practice.

It is vitally important that decision makers throughout an organisation

appreciate the impact of their decisions on the likely success of all the

other, interconnected parts of the organisation. Unethical business

practices undertaken in one part of the business can have disastrous

consequences elsewhere. For example, an unethical marketing

campaign could have a knock-on impact on the sales of a business,

leading to a reduction in production and a subsequent cut in purchasing

and staffing.

| Test your understanding 4 |

| Suggest ways in which ethical issues would influence the firm’s financial policies in relation to the following: • shareholders • suppliers • customers • investment appraisal • charity. |

8 The environmental impact of the financial manager’s decisions

In the last few years, the issue of sustainable development has taken on greater

urgency as concerns about the long-term impact of business on the planet have

grown.

The United Nations defines sustainable development as:

Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising

the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

The underlying principle for firms is that environmental, social and economic

systems are interdependent and decisions must address all three concerns

coherently.

In developing corporate policies and objectives, specific attention should be

given to matters of sustainability and environmental risk.

| Specific examples of environmental issues |

| Carbon-trading and emissions Firms with high energy use may need to set objectives for their emissions of greenhouse gases in order to achieve targets set by governments under the Kyoto Protocol. This may include: • reducing emissions to reduce liability for energy taxes • entering a carbon emissions trading scheme. |

The Kyoto Protocol

The Kyoto Protocol was negotiated by 160 nations in 1997. It is an

attempt to limit national emissions of greenhouse gases in order to slow

or halt an associated change of climate. The agreement sets emission

targets for the individual nations. Australia, for instance, agreed to limit its

annual emission by the year 2012 to no more than 108% of its emission

in 1990.

The Protocol was negotiated based on an economic mechanism of

‘carbon trading’ evolving; i.e. nations issuing permits for carbon emission,

set to match the targets set by the Kyoto Protocol or its follow-on

agreements. The permits, tradeable, both nationally and internationally,

are intended to operate such that market forces ultimately replace

government direction in the process of encouraging more efficient use of

fossil fuel.

Individual companies will be able to decide whether to spend money on

new ‘carbon efficient’ technology or on the acquisition of carbon credits

from those industries or countries which have a surplus.

In the UK for example, there is a carbon emissions trading scheme,

which is run by the Department of Energy and Climate Change. Details

are provided here only to provide a clear picture of how such a scheme

works.

The UK scheme

Organisations in the scheme volunteer to reduce emissions in return for a

financial incentive provided by the government. They are set emissions

targets based on a formula. If they overachieve they can sell or bank the

excess allowances. If they underachieve they must buy the allowances

they need.

Some firms already have targets as a result of Climate Change Levy

Agreements (CCLAs – see below) set up to help businesses with

intensive energy use mitigate the effects of the UK energy tax. These

firms can sell their surpluses or buy needed credits.

Other firms, even if they do not emit greenhouse gases, may set up an

account to trade in the allowances.

The climate change levy is a tax on the use of energy in industry,

commerce and the public sector, with offsetting cuts in employers’

National Insurance Contributions – NICs – and additional support for

energy efficiency schemes and renewable sources of energy. The levy

forms a key part of the Government’s overall Climate Change

Programme.

The role of an environment agency

Government environment agencies (in the UK – Defra – the Department

for the environment, food and rural affairs) work to ensure that business

meets the environmental targets set internationally. They set local

business targets in key areas such as:

• energy conservation

• recycling

• protection of the countryside

• sustainable development.

which will need to be taken into account when setting objectives for the

business as a whole.

| Triple Bottom Line (TBL) reporting |

| Environmental audits and the triple bottom line approach First coined in the mid-1990s, the phrase triple bottom line, refers to the need for companies to focus on the: • economic value and • environmental value and • social value. both added and destroyed by the firm. Providing stakeholders with corporate performance data in each of these areas is known as triple bottom line reporting. In order to provide credible data, companies will need to: • set up a suitable management system to capture the information • ensure the reports are subject to an appropriate audit scrutiny. Triple bottom line reporting A triple bottom line approach requires a shift in culture and focus, and the development of appropriate policies and objectives. It can also be used as a framework for measuring and reporting corporate performance. Many leading companies are now publishing environmental and sustainability reports – demonstrating to stakeholders that they are addressing these issues. |

In order to provide meaningful data, a business must be able to assess

the environmental and social impact of their operations. One way to do

this is to adopt the framework provided by ISO 14000. ISO 14000 is a

series of international standards on environmental management.

It provides a framework for the development of an environmental

management system and a supporting audit programme.

Environmental auditing is a systematic, documented, periodic and

objective process in assessing an organisation’s activities and services in

relation to:

• Assessing compliance with relevant statutory and internal

requirements.

• Facilitating management control of environmental practices.

• Promoting good environmental management.

• Maintaining credibility with the public.

• Raising staff awareness and enforcing commitment to departmental

environmental policy.

• Exploring improvement opportunities.

• Establishing the performance baseline for developing an

Environmental Management System (EMS).

| Test your understanding 1 |

| Shareholders – The support of shareholders is necessary for the smooth running of the business. Actions from awkward questions at AGMs through to (in the worst case) a vote to remove the directors, are available to aggrieved shareholders. The goals set by a company should reflect their concerns as key stakeholders, and communication of them should reassure shareholders that the firm is acting as they would wish. Government – Government targets and policies often include specific expectations of the business community. Keeping government departments informed of activities and consulting in key areas can help prevent later government intervention, or punitive action from regulators. Customers – A business will struggle to continue without the support of its customers. Today, consumers are increasingly concerned about how the goods and services they buy are provided. Companies are therefore keen to demonstrate their commitment to ethical, environmental policies. They can do so by communicating clearly the specific goals and policies they have developed to ensure they meet customer expectations. Suppliers – If shareholder and customer concern over the provenance of the supply chain is to be addressed, it is essential that suppliers are clear about the expectations of the company. This may include requirements for their own suppliers, the treatment of their own staff, the way in which their products are produced etc. The company must ensure such policies are clear and enforced. Community at large – The larger community may not have any direct involvement with the company but can be quick to take action such as arranging boycotts or lobbying if it disapproves of the way the company conducts business. Reassurance about corporate goals can reduce the likelihood of disruptive action. Managers/directors/employees – Senior staff will need to be kept fully up-to-date about all goals and policies set by the firm, so they can apply them when taking decisions. Explaining to employees why decisions are being taken can help to ensure co-operation in their implementation. |

| Test your understanding 2 |

| Treasury is the function concerned with the provision and use of finance and thus handles the acquisition and custody of funds whereas the Financial Control Department has responsibility for accounting, reporting and control. The roles of the two departments in the proposed investment are as follows: Evaluation • Treasury will quantify the cost of capital to be used in assessing the investment. • The financial control department will estimate the project cash flows. Implementation • Treasury will establish corporate financial objectives, such as wanting to restrict gearing to 40%, and will identify sources and types of finance. • Treasury will also deal with currency management – dealing in foreign currencies and hedging currency risks – and taxation. • The financial control department will be involved with the preparation of budgets and budgetary control, the preparation of periodic financial statements and the management and administration of activities such as payroll and internal audit. Interaction • The Treasury Department has main responsibility for setting corporate objectives and policy and Financial Control has the responsibility for implementing policy and ensuring the achievement of corporate objectives. This distinction is probably far too simplistic and, in reality, both departments will make contributions to both determination and achievement of objectives. • There is a circular relationship in that Treasurers quantify the cost of capital, which the Financial Controllers use as the criterion for the deployment of funds; Financial Controllers quantify projected cash flows which in turn trigger Treasurers’ decisions to employ capital. |

| Test your understanding 3 |

| Strategic issues Competitive advantage – currently the firm is a differentiator (it competes on quality rather than cost). The new entrants into the market seem to be cost leaders. Undertaking Project 1 might reduce the quality of the Ribs Co tools and undermine the firm’s long standing competitive advantage. Fit with environment – clearly the environment has changed in the last 12 months. The new imports indicate that perhaps the economic environment has changed (movement in exchange rates? removal of import tariffs?), and also that customers are seemingly looking for cheaper tools (social factor). Ribs Co is right to try to find new projects which enable it to compete in this new environment. Stakeholder reactions – the shareholders are not happy, so they will welcome the new projects (providing the directors communicate the positive NPV information effectively). However, other stakeholders are likely to be less impressed. For example, under Project 1 there are likely to be job cuts in the domestic market, so the employees, local community and domestic government are likely to be unhappy about this option. The directors must consider the long term consequences of upsetting these key stakeholders in the short term. Risk – Project 2 appears to be the more risky option – it involves exporting goods into a foreign market where Ribs Co currently has no operations. There is no guarantee that the Ribs tools will be a success in the new market. However, there is huge potential under this option. Clearly the domestic market is becoming saturated, so perhaps now is the time for Ribs to seek out new opportunities abroad. Financial issues Positive NPVs – both prospective projects have positive NPVs, so theoretically shareholder wealth should increase whichever is undertaken. However, the cash flow estimates need to be analysed and sensitivity analysis should be performed to see what changes in estimates can be tolerated. Impact on cost of capital – Ribs Co’s current cost of capital has been used for discounting the projects. However the change in risk (caused by the exposure to foreign factors in both projects) is likely to change the cost of capital. Financing – both projects are likely to require significant short term capital expenditure. The directors will have to consider the size of investment required, and the firm’s target gearing ratio, as they assess whether debt or equity funding should be sought. |

| Test your understanding 4 |

| Shareholders: • Providing timely and accurate information to shareholders on the company’s historical achievements and future prospects. Suppliers: • paying fair prices • attempting to settle invoices promptly • co-operating with suppliers to maintain and improve the quality of inputs • not using or accepting bribery or excess hospitality as a means of securing contracts with suppliers. Customers: • charging fair prices • offering fair payment terms • honouring quantity and settlement discounts • ensuring sufficient quality control processes are built in that goods are fit for purpose. Investment appraisal: • payment of fair wages • upholding obligations to protect, preserve and improve the environment • only trading (both purchases and sales) with countries and companies that themselves have appropriate ethical frameworks. Charity: • Developing a policy on donations to educational and charitable institutions. |

One thought on “The role and responsibility of the financial manager”