Exam focus

Professional issues are usually examined alongside ethical issues but can be examined in their own right. Typical exam questions may ask for respective responsibilities of management and auditors in respect of fraud & error or laws & regulations, or could ask whether an auditor is liable in a given situation.

Laws and regulations

Guidance relating to laws and regulations in an audit of financial statements is provided in ISA 50 Consideration of Laws and Regulations in an Audit of

Financial Statements.

Non-compliance with laws and regulations may lead to material misstatement if liabilities for non-compliance are not recorded, contingent liabilities are not disclosed, or if they lead to going concern issues which would require disclosure or affect the basis of preparation of the financial statements.

‘Non-compliance’ means acts of omission or commission by the entity, either intentional or unintentional, which are contrary to the prevailing laws or regulations. Non-compliance must specifically relate to the business activities i.e. transactions entered into on behalf of the company. It does not include personal misconduct.

[ISA 50, ]

Responsibilities are considered from the perspective of both auditors and management.

Responsibilities of management

It is the responsibility of management, with the oversight of those charged with governance, to ensure that the entity’s operations are conducted in accordance with relevant laws and regulations, including those that determine the reported amounts and disclosures in the financial statements. [ISA 50, 3]

Management responsibilities

In order to help prevent and detect non-compliance, management can implement the following policies and procedures:

Monitoring legal requirements applicable to the company and ensuring that operating procedures are designed to meet these requirements.

Instituting and operating appropriate systems of internal control.

Developing, publicising and following a code of conduct.

Ensuring employees are properly trained and understand the code of conduct.

Monitoring compliance with the code of conduct and acting appropriately to discipline employees who fail to comply with it.

Engaging legal advisors to assist in monitoring legal requirements.

Maintaining a register of significant laws and regulations with which the entity has to comply.

In larger entities, these policies and procedures may be supplemented by assigning appropriate responsibilities to:

An internal audit function An audit committee

A compliance function. [ISA 50, A ]

Responsibilities of the auditor

The auditor is responsible for obtaining reasonable assurance that the financial statements taken as a whole, are free from material misstatement, whether caused by fraud or error.

[ISA 00 Overall Objectives of the Independent Auditor and the Conduct of an Audit in Accordance with International Standards on Auditing, a].

Therefore, in conducting an audit of financial statements the auditor must perform audit procedures to help identify non-compliance with laws and regulations that may have a material impact on the financial statements.

The auditor must obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence regarding compliance with:

Laws and regulations generally recognised to have a direct effect on the determination of material amounts and disclosures in the financial statements e.g. company law, tax law, applicable financial reporting framework . [ISA 50, 6a]

Other laws and regulations that may have a material impact on the financial statements e.g. environmental legislation . [6b]

Further discussion of auditor responsibility

IFAC recognises that the auditors have a role in relation to non-compliance with laws and regulations. Auditors plan, perform and evaluate their audit work with the aim of providing reasonable, though not absolute, assurance of detecting any material misstatement in the financial statements which arises from non-compliance with laws or regulations. However, auditors cannot be expected to be experts in all the many different laws and regulations where non-compliance might have such an effect. There is also an unavoidable risk that some material misstatements may not be detected due to the inherent limitations in auditing.

Audit procedures to identify instances of non-compliance

Obtaining a general understanding of the legal and regulatory framework applicable to the entity and the industry, and of how the entity is complying with that framework. [ISA 50, ]

Enquiring of the management and those charged with governance as to whether the entity is in compliance with such laws and regulations. [ 4a]

Inspecting correspondence with relevant licensing or regulatory authorities. [ 4b]

Remaining alert to the possibility that other audit procedures applied may bring instances of non-compliance to the auditor’s attention. [ 5]

Obtaining written representation from the directors that they have disclosed to the auditors all those events of which they are aware which involve possible non-compliance, together with the actual or contingent consequences which may arise from such non-compliance. [ 6]

How to obtain a general understanding

Use the auditor’s existing understanding of the industry.

Update the auditor’s understanding of those laws and regulations that directly determine reported amounts and disclosures in the financial statements.

Enquire of management as to other laws and regulations that may be expected to have a fundamental effect on the operations of the entity.

Enquire of management concerning the entity’s policies and procedures regarding compliance with laws and regulations.

Enquire of management regarding the policies or procedures adopted for identifying, evaluating and accounting for litigation claims.

[ISA 50, A7]

Investigations of possible non-compliance

When the auditor becomes aware of information concerning a possible instance of non-compliance with laws or regulations, they should:

Understand the nature of the act and circumstances in which it has occurred.

Obtain further information to evaluate the possible effect on the financial statements.

[ISA 50, ]

Audit procedures when non-compliance is identified

Enquire of management of the penalties to be imposed.

Inspect correspondence with the regulatory authority to identify the consequences.

Inspect board minutes for management’s discussion on actions to be taken regarding the non-compliance.

Enquire of the company’s legal department as to the possible impact of the non-compliance.

Reporting non-compliance

The auditor should report non-compliance to management and those charged with governance. [ISA 50, ]

If the auditor believes the non-compliance is intentional and material the matter should be reported to those charged with governance. [ 3]

If the auditor suspects management or those charged with governance are involved in the non-compliance, the matter should be reported to the audit committee or supervisory board. [ 4]

If the non-compliance has a material effect on the financial statements, a qualified or adverse opinion should be issued. [ 5]

The auditor should also consider whether they have any responsibility to report non-compliance to third parties e.g. to a regulatory authority. [ ]

Engagement withdrawal

The auditor may decide that they need to withdraw from the engagement i.e.

resign as auditor if:

The non-compliance with laws and regulations is so serious that they can no longer maintain a client relationship.

There has been a breakdown of trust between the auditor and management.

The auditor has doubts about the competence of management.

The auditor should seek legal advice before taking this course of action.

[ISA 50, A ]

Responding to Non-Compliance with Laws and Regulations

This publication sets out the professional accountant’s responsibilities when non-compliance with laws and regulations NOCLAR is identified or suspected.

The accountancy profession is expected to act in the public interest. This means considering matters that could cause harm to investors, creditors, employees or the general public.

Examples of laws and regulations covered by this publication:

Fraud, corruption and bribery

, terrorist financing and proceeds of crime Securities markets and trading

Banking and financial products and services

Data protection

Tax and pension liabilities and payments Environmental protection

Public health and safety.

Matters which are not covered by this publication are:

Matters which are clearly inconsequential

Personal misconduct unrelated to the business activities of the client.

Responsibilities of the professional accountant Obtain an understanding of the matter

Apply knowledge, professional judgment and expertise. The accountant may consult on a confidential basis with others within the firm, a network firm or a professional body, or with legal counsel.

Discuss the matter with management and those charged with governance. This may help to obtain an understanding of the matter and may prompt management to investigate the matter.

Address the matter

Discuss the matter with management and advise them to take appropriate action such as:

Rectify, remediate or mitigate the consequences of the non-compliance.

Deter the commission of non-compliance where it has not yet occurred.

Disclose the matter to an appropriate authority where required by law or regulation or where considered necessary in the public interest.

Determine what further action is needed

Assess the appropriateness of management’s response including whether:

The response is timely.

The non-compliance has been adequately investigated.

Action has been, or is being, taken to rectify, remediate or mitigate the consequences of non-compliance.

Action has been or is being taken to deter the commission of any non-compliance where it has not yet occurred.

Appropriate steps have been taken to reduce the risk of re-occurrence.

The non-compliance has been disclosed to an appropriate authority where appropriate.

The professional accountant should consider whether management integrity is in doubt e.g. if the accountant suspects management are involved in the non-compliance or if management are aware of the non-compliance but have not reported it to an appropriate authority within a reasonable period.

Further action may include:

Disclosure of the matter to a regulatory authority even when there is no legal or regulatory requirement to do so.

Withdrawal from the engagement and the professional relationship where permitted by law or regulation.

The professional accountant should provide the successor accountant with all such facts about the non-compliance that they need to be aware of before deciding whether to accept the audit.

Professional accountants who are not the external auditor of the entity

If the professional accountant is performing non-audit services for an audit client of the firm, the matter should be communicated within the firm.

If the professional accountant is performing non-audit services for an audit client of a network firm, the matter should be communicated in accordance with the network’s procedures or directly to the engagement partner.

If the professional accountant is performing non-audit services to a client that is not an audit client of the firm or a network firm, the matter should be communicated to the client’s external auditor unless this would be contrary to law or regulation.

A professional accountant in business should discuss non-compliance identified or suspected with their immediate superior or the next higher level if they suspect the superior is involved in the matter.

Fraud and error, misstatements and irregularities

Guidance regarding responsibility to consider fraud and error in an audit of financial statements is provided in ISA 40 The Auditor’s Responsibilities Relating to Fraud in an Audit of Financial Statements.

Definitions Irregularity

Irregularity is the collective term for fraud, error, breaches of laws and regulations, and deficiencies in the design or operating effectiveness of controls. An irregularity may or may not result in a misstatement in the financial statements.

Misstatement

A difference between the amount, classification, presentation, or disclosure of a reported financial statement item and the amount, classification, presentation, or disclosure that is required for the item to be in accordance with the applicable financial reporting framework.

[ISA 450 Evaluation of Misstatements Identified During the Audit, 4a]

Misstatements can arise from fraud or error. The distinguishing factor between fraud and error is whether the underlying action that results in the misstatement of the financial statements is intentional or unintentional.

Fraud

Fraud is an intentional act involving the use of deception to obtain an unjust or illegal advantage. It may be perpetrated by one or more individuals among management, employees or third parties.

[ISA 40, a]

There are two categories of fraud that are of concern to auditors:

Fraudulent financial reporting, and Misappropriation of assets.

[ISA 40, 3]

Misappropriation of assets means theft e.g. the creation of dummy suppliers or ghost employees to divert company funds into a personal bank account.

Fraudulent financial reporting in particular may be viewed as more prevalent nowadays for the following reasons:

Increased pressure on companies to publish improved results to shareholders and the markets.

Greater emphasis on performance related remuneration to comply with corporate governance best practise incentivises directors to inflate profits to achieve bigger bonuses.

When trading conditions are difficult as has been seen over recent years, additional finance may be required. Finance providers are likely to want to rely on the financial statements when making lending decisions. Directors may make the financial statements look more attractive in order to secure the finance.

If existing borrowings are in place with covenants attached, directors may manipulate the financial statements to ensure the covenants are met.

Error

An error can be defined as an unintentional misstatement in financial statements, including the omission of amounts or disclosures, such as the following:

A mistake in gathering and processing data from which financial statements are prepared.

An incorrect accounting estimate arising from oversight or a misinterpretation of facts.

A mistake in the application of accounting principles relating to measurement, recognition, classification, presentation or disclosure.

[ISA 450, A ]

Errors are normally corrected by clients when they are identified. If a material error has been identified but has not been corrected, it will require the audit opinion to be modified.

Management responsibilities

The primary responsibility for the prevention and detection of fraud rests with both those charged with governance of an entity and with management.

Management should:

Place a strong emphasis on fraud prevention and error reduction.

Reduce opportunities for fraud to take place.

Ensure the likelihood of detection and punishment for fraud is sufficient to act as a deterrent.

Ensure controls are in place to provide reasonable assurance that errors will be identified.

Foster, communicate and demonstrate a culture of honesty & ethical behaviour.

Consider potential for override of controls or manipulation of financial reporting.

Implement and operate adequate accounting and internal control systems. [ISA 40, 4]

Auditor responsibilities

Provide reasonable assurance that the financial statements are free from material misstatement, whether caused by fraud or error. [ISA 40, 5]

Apply professional scepticism and remain alert to the possibility that fraud could take place. [ ]

Consider the potential for management override of controls and recognise that audit procedures that are effective for detecting error may not be effective for detecting fraud. [ ]

This can be achieved by performing the following procedures:

Discuss the susceptibility of the client’s financial statements to material misstatement due to fraud with the engagement team. [ 5]

Enquire of management regarding their assessment of fraud risk, the procedures they conduct and whether they are aware of any actual or suspected instances of fraud. [ ]

Enquire of the internal audit function to establish if they are aware of any actual or suspected instances of fraud. [ 9]

Enquire of those charged with governance with regard to how they exercise oversight of management processes for identifying the risk of fraud and whether they are aware of any actual or suspected fraud. [ 0]

Consideration of relationships identified during analytical procedures. [ ]

Due to the inherent limitations of an audit, there is an unavoidable risk that some material misstatements may not be detected, even though the audit is properly planned and performed in accordance with ISAs. This risk is greater in relation to misstatement due to fraud, rather than error, because of the potentially sophisticated nature of organised criminal schemes. [5]

Responses to an assessed risk of fraud

Assign responsibility to personnel with appropriate knowledge and skill. [ISA 40, 9a]

Evaluate whether the accounting policies of the entity indicate fraudulent financial reporting. [ 9b]

Use unpredictable procedures to obtain evidence. [ 9c]

Procedures

Review journal entries made to identify manipulation of figures recorded or unauthorised journal adjustments:

– Enquire of those involved in financial reporting about unusual activity relating to adjustments.

– Select journal entries and adjustments made at the end of the reporting period.

– Consider the need to test journal entries throughout the period. [3 a]

Review management estimates for evidence of bias:

– Evaluate the reasonableness of judgments and whether they indicate any bias on behalf of management.

– Perform a retrospective review of management judgments reflected in the prior year. [3 b]

Review transactions outside the normal course of business, or transactions which appear unusual and assess whether they are indicative of fraudulent financial reporting.

[3 c]

Obtain written representation from management and those charged with governance that they:

– acknowledge their responsibility for internal controls to prevent and detect fraud.

– have disclosed to the auditor the results of management’s fraud risk assessment

– have disclosed to the auditor any known or suspected frauds.

– have disclosed to the auditor any allegations of fraud affecting the entity’s financial statements.

[39]

Reporting of fraud and error

If the auditor identifies a fraud they must communicate the matter on a timely basis to the appropriate level of management i.e. those with the primary responsibility for prevention and detection of fraud . [ISA 40, 40]

If the suspected fraud involves management the auditor must communicate the matter to those charged with governance. If the auditor has doubts about the integrity of those charged with governance they should seek legal advice regarding an appropriate course of action. [4 ]

In addition to these responsibilities the auditor must also consider whether they have a responsibility to report the occurrence of a suspicion to a party outside the entity. Whilst the auditor does have an ethical duty to maintain confidentiality, it is likely that any legal responsibility will take precedence. In these circumstances it is advisable to seek legal advice. [43]

If the fraud has a material impact on the financial statements the auditor’s report will be modified. When the auditor’s report is modified, the auditor will explain why it has been modified and this will make the shareholders aware of the fraud.

Engagement withdrawal

In exceptional circumstances the auditor may consider it necessary to withdraw from the engagement. This may be if fraud is being committed by management or those charged with governance and therefore casts doubt over the integrity of the client and reliability of representations from management.

The auditor should seek legal advice first as withdrawal may also require a report to be made to the shareholders, regulators or others. [ISA 40, 3 ]

Current issue: The future of fraud and the audit

Fraud is a controversial area for auditors, and the extent of auditor responsibility for the prevention and detection of fraud continues to be debated by those in the profession, governments and other users of financial statements.

The Kingston Cotton Mill case 96 emphasised that the reader of the auditor’s report should have a realistic viewpoint of what the auditor’s role should actually be.

The judge in the case set the benchmark for auditor responsibility when he said “An auditor is not bound to be a detective, or… to approach his work with suspicion, or with a foregone conclusion that there is something wrong. He is a watchdog, not a bloodhound.”

Auditors do have a recognised responsibility for considering fraud when conducting an audit of financial statements, but the primary responsibility for fraud and error continues to rest with management, and those charged with governance. However, the auditor’s responsibility with respect to fraud could change.

Auditors are currently responsible for detecting material misstatements whether caused by fraud or error. However, misstatements due to fraud are, by their very nature, extremely difficult to detect. Auditors are not trained as, nor expected to be, forensic investigators and even the most experienced auditor may have failed to detect a material misstatement caused by fraud. The auditor’s responsibility for detecting material misstatements could be limited to exclude those caused by fraud.

Conversely, many users would like to see auditors’ responsibility for fraud extended. In order to achieve this, auditors would have to be given the training necessary to identify fraud. In addition, the extent of auditor’s responsibilities would have to be defined. It would not be realistic to expect the auditor to detect all fraud. Some frauds especially where collusion is involved are almost impossible to identify. However, auditors could be given responsibility for performing audit procedures specifically to detect fraud, possibly in those areas that are more susceptible to fraud e.g. payroll .

The audit profession is dynamic and subject to much debate at the current time. It is not possible to know what the future holds, but perhaps auditors will be required to move towards the role of a bloodhound in the not too distant future.

Not absolute assurance

An auditor cannot provide absolute assurance over the accuracy of the financial statements because of such factors as:

Nature of financial reporting:

– The use of judgment by management.

– Subjectivity of items in the financial statements. Nature of audit procedures:

– Management may not provide complete information to the auditor.

– Fraud may be sophisticated and well concealed.

– The auditor does not have legal powers to conduct an official investigation into wrongdoing.

The need to conduct the audit within a reasonable time and at a reasonable cost, therefore all items cannot be tested.

[IAS 00 Overall Objectives of the Independent Auditor and the Conduct of an Audit in Accordance with International Standards on Auditing, A47]

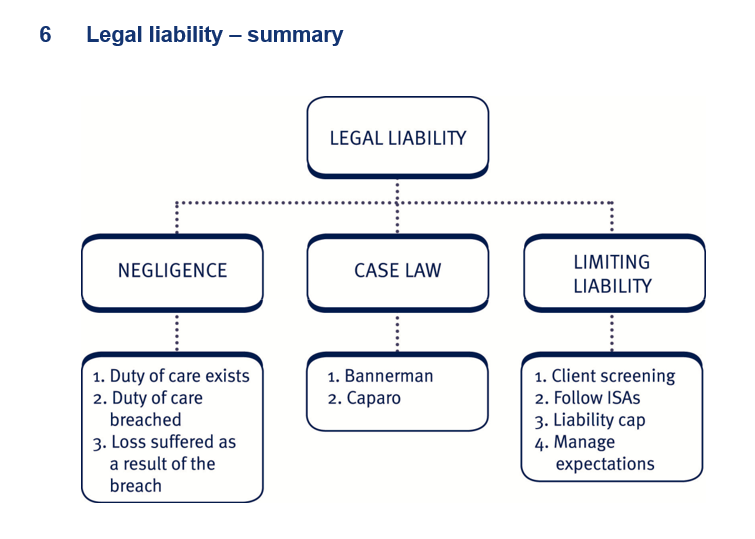

3 Legal liability

Liability to the client and liability to third parties

Liability to the client

Liability to the client arises from contract law. The company has a contract with the auditor, the engagement letter, and hence can sue the auditor for breach of contract if the auditor delivers a negligently prepared report.

When carrying out their duties the auditor must exercise due care and skill.

Generally, if auditors can show that they have complied with generally accepted auditing standards, they will not have been negligent.

Liability to third parties

A third party i.e. a person who has no contractual relationship with the auditor may be able to sue the auditor for damages, i.e. a financial award.

In the tort of negligence, the plaintiff i.e. the third party must prove that:

- The defendant e. the auditor owes a duty of care, and

- The defendant has breached the appropriate standard of care as discussed above, and

- The plaintiff has suffered loss as a direct result of the defendant’s breach.

The critical matter in most negligence scenarios is whether a duty of care is owed in the first place.

When is a duty of care owed?

A duty of care exists when there is a special relationship between the parties, i.e. where the auditors knew, or ought to have known, that the audited financial statements would be made available to, and would be relied upon by, a particular person or class of person .

The injured party must therefore prove:

The auditor knew, or should have known, that the injured party was likely to rely on the financial statements.

The injured party has sufficient ‘proximity’, i.e. belongs to a class likely to rely on the financial statements.

The injured party did in fact so rely.

The injured party would have acted differently if the financial statements had shown a different picture.

Has the auditor exercised due professional care?

The auditor will have exercised due professional care if they have:

Complied with the most up-to-date professional standards and ethical requirements.

Complied with the terms and conditions of appointment as set out in the letter of engagement and as implied by law.

Employed competent staff who are adequately trained and supervised in carrying out instructions.

Has the injured party suffered a loss?

This is normally a matter of fact. For example, if X relies on the audited financial statements of Company A and pays $5 million to buy the company, but it soon becomes clear that the company is worth only $ million, then a loss of

$4 million has been incurred.

Criminal vs. civil

Auditors’ liability can be categorised under the following headings:

Civil or criminal liability arising under legislation Liability arising from negligence.

Civil liability

Auditors may be liable in the following circumstances:

To third parties suffering loss as a result of relying on a negligently prepared auditor’s report.

Under insolvency legislation to creditors – auditors must be careful not to be implicated in causing losses to creditors alongside directors.

Under tax legislation – particularly where the auditor is aware of tax frauds perpetrated by the client.

Under financial services legislation to investors. Under stock exchange legislation and/or rules.

The only possible penalty for a civil offence is payment of damages.

Criminal liability

Criminal liability can arise in the following circumstances:

Acting as auditor when ineligible.

Fraud, such as: theft, bribery and other forms of corruption, falsifying accounting records, and knowingly or recklessly including misleading matters in an auditor’s report.

Insider dealing.

Knowingly or recklessly making false statements in connection with the issue of securities.

Penalties for criminal liability include fines and/or imprisonment.

In addition to the various civil and criminal liabilities the professional bodies that regulate accountants and auditors have various sanctions, such as warnings, fines, reprimands, severe reprimands and exclusion from membership for misconduct by members. Conviction of a criminal offence involving financial misconduct is normally sufficient to warrant exclusion from membership of a professional body.

Case Study: Bannerman

The Bannerman case Royal Bank of Scotland RBS v Bannerman

Johnstone Maclay 00

RBS provided overdraft facilities to APC Limited and Bannerman were APC’s auditors. The relevant facility letters between RBS and APC contained a clause requiring APC to send RBS, each year, a copy of the annual audited financial statements. In 99 APC was put into receivership with approximately $ 3. 5 million owing to RBS. RBS claimed that, due to a fraud, APC’s financial statements for the previous years had misstated the financial position of APC and Bannerman had been negligent in not detecting the fraud. RBS contended that it had continued to provide the overdraft facilities in reliance on Bannerman’s unmodified opinions.

Bannerman applied to the court for an order striking out the claim on the grounds that, even if all the facts alleged by RBS were true, the claim could not succeed in law because Bannerman owed no duty of care to RBS. The judge held that the facts pleaded by RBS were sufficient in law to give rise to a duty of care and so the case could proceed to trial. The judge held that, although there was no direct contact between Bannerman and RBS, knowledge gained by Bannerman in the course of their ordinary audit work was sufficient, in the absence of any disclaimer, to create a duty of care owed by Bannerman to RBS. In order to consider APC’s ability to continue as a going concern, Bannerman would have reviewed the facilities letters and so would have become aware that the audited financial statements would be provided to RBS for the purpose of RBS making lending decisions. Having acquired this knowledge, Bannerman could have disclaimed liability to RBS but did not do so. The absence of such a disclaimer was an important circumstance supporting the finding of a duty of care.

Case Study: Caparo

The Caparo case Caparo Industries v Dickman and others 9 4

Caparo Industries took over Fidelity plc in 9 4 and alleged that it increased its shareholding on the basis of Fidelity’s accounts, audited by Touche Ross. Caparo sued Touche Ross for alleged negligence in the audit, claiming that the stated $ .3 million profit for the year to 3 March 9 4 should have been reported as a loss of $460,000. It was held in this case that the auditors owed no duty of care in carrying out the audit to individual shareholders or to members of the public who relied on the accounts in deciding to buy shares in the company. The House of Lords looked at the purpose of statutory accounts. They concluded that such accounts, on which the auditor must report, are published with the principal purpose of providing shareholders as a class with information relevant to exercising their proprietary interests in the company. They are not published to assist individuals whether existing shareholders or not to speculate with a view to profits.

Case Study: ADT Ltd v BDO Binder Hamlyn ADT Ltd v BDO Binder Hamlyn 995

BDO BH were the joint auditors of the Britannia Security Systems Group. Before the 9 9 audit was finished, ADT were considering bidding for Britannia, so an ADT representative met the BDO BH audit partner and asked him to confirm that the audited accounts gave a true and fair view and that he had learnt nothing subsequently which cast doubt on the accounts. The partner said that BDO BH stood by the accounts and there was nothing else that ADT should be told. ADT then bought Britannia for $ 05 million, but it was found to be worth only $40 million.

It was held that BDO BH owed ADT a duty of care when the partner made his statements, and the accounts had been negligently audited, so ADT were awarded $ 65 million plus interest. The shortfall in BH’s insurance cover was $34 million. The partners were individually liable for that amount. BH appealed, and ADT agreed an out-of-court settlement.

Case Study: Lloyd Cheyham v Littlejohn de Paula Lloyd Cheyham v Littlejohn de Paula 9 5

Littlejohn de Paula successfully defended themselves against a negligence claim in this case by showing:

That they had followed the standard expected of the normal auditor, i.e. auditing standards.

That their working papers were good enough to show consideration of the problems raised by the plaintiff and reasonable decisions made after consideration.

That the plaintiff had not made all reasonable enquiries one could expect when purchasing a company. For example a review of the business was not undertaken upon investigating the purchase but only after purchase.

The judge, therefore, held that far too much reliance was placed on the accounts by the plaintiff and he awarded costs against the plaintiff to the defendant.

Restricting auditors’ liability

Audit firms may take the following steps to minimise their exposure to negligence claims:

Restrict the use of the auditor’s report and assurance reports to their specific, intended purpose.

Engagement letter clause to limit liability to third parties.

Screening potential audit clients to accept only clients where the risk can be managed.

Take specialist legal advice where appropriate.

Respective responsibilities and duties of directors and auditors communicated in the engagement letter and auditor’s report to minimise misunderstandings.

Insurance – professional indemnity insurance PII . Carry out high quality audit work.

Take on LLP status.

Set a liability cap with clients.

The impact of limiting audit liability

Some commentators have argued that limiting audit liability is contrary to the public interest, since auditors will be less motivated to do quality work if they know that they won’t have to pay for their mistakes.

Other commentators say that this ignores the professional nature of the audit discipline. People choose to be audit partners because they want to do a high quality job for themselves and for society.

Methods of limiting audit liability

- Liability caps

This could be a fixed amount as in Germany or a multiple of the audit fee. A possible adverse effect of the latter would be to either reduce the quality of work done, or to reduce the fee, as the lower the fee, the lower the liability.

In the UK such agreements were illegal until the Companies Act 006, which now permits liability limitation agreements between auditors and companies, subject to shareholders’ approval. The Act does not specify what sort of limit can be agreed, so a fixed cap, or a multiple of fees, or any other type, are all now possible.

- Modification of the ‘joint and several liability’ principle. Auditors are jointly and severally liable with directors where negligence claims are made, either under legislation, or under case law. This means that directors and auditors are held responsible together for the issue of negligently prepared and audited financial statements. If, say, the auditors and directors share the blame for falsifying records e. the auditors did not detect it , the auditor may bear all of the costs if the directors have no resources to pay. The objective is to protect the plaintiff and maximise their chances of recovery of losses.

An associated problem is the fact that all partners and directors are responsible for the misconduct of other partners and directors in audit firms, regardless of whether they were directly involved in a particular audit. In the US, and now the UK, this problem is partly dealt with by limited liability partnerships.

- Compulsory insurance for directors

If directors are partly to blame then they should be responsible for their share of the costs. If auditors must hold compulsory insurance in case of any claims it could be argued that directors should also hold insurance.

Insurance for accountancy firms

One of the obligations of practising as a professional accountant is to ensure that, if an accountant’s negligence has caused loss to a client, the accountant has an insurance policy to ensure that he can pay any damages awarded.

Professional indemnity insurance PII is insurance taken out by an accountant against claims made by clients and third parties arising from work that the accountant has carried out.

Fidelity guarantee insurance FGI is insurance taken out by an accountant against any liability arising through acts of fraud or dishonesty by any partner or employee in respect of money or goods held in trust by the accountancy firm.

The expectation gap

The expectation gap is the gap between what the public believe that auditors do or ought to do and what they actually do.

This expectation gap can be categorised into:

Standards and performance gap – where users believe auditing standards to be more comprehensive than they actually are and therefore the auditor does not perform the level of work the user expects.

Liability gap – where users do not understand to whom the auditor is legally responsible.

Bridging the expectation gap

Recent developments and proposals include:

Educating users to reduce the standards gap e.g.

– Auditor’s reports now include greater detail of the auditor’s responsibilities and key audit matters.

– Written representation letters require management to sign to acknowledge their responsibilities in respect of the financial statements.

Increasing communication between the auditor and those charged with governance regarding their respective responsibilities.

Increasing the scope of the work of the auditor e.g. to require greater detection of fraud and error.

Expectation gap: Examples

Users believe that auditors are responsible for preventing and detecting fraud and error, while ISAs require auditors to only have a reasonable expectation of detecting material fraud and error.

Users believe that they can sue the auditors if a company fails, while auditors maintain that it is the directors’ responsibility to run their business as a going concern, It is not the auditor’s function to protect individual shareholders if they make a poor investment decision.

Users believe the audit firm will report externally all ‘wrong doing’ e.g. non-compliance with laws and regulations. The auditor will only report externally where there is a duty to do so.

Users believe the audit firm will highlight poor performance by management. The objective of the auditor is to express an opinion on the truth and fairness of the financial statements. If poor decisions have been made but the financial effects of these decisions have been properly reflected in the financial statements, there is nothing to mention in the auditor’s report.

Disclaimer statements

Reaction to the Bannerman decision

In the Bannerman case the judge commented that, if the auditors had inserted a disclaimer statement in their report, then they would have had no legal liability to RBS who was suing them.

Following this case, the ICAEW recommended additional wording to be routinely included in all auditor’s reports by ICAEW members:

‘This report is made solely to the company’s members as a body. Our audit work has been carried out so that we might state to the company’s members those matters we are required to state to them in an audit report and for no other purpose. We do not accept responsibility to anyone other than the company and the company’s members as a body, for our audit work or for the opinions we have formed.’

The ACCA’s view in Technical Factsheet 4 is that standard disclaimer clauses should be discouraged since they could have the effect of devaluing the auditor’s report. Disclaimers of responsibility should be made in appropriate, defined circumstances e.g. where the auditor knows that a bank may rely on a company’s financial statements but the ACCA does not believe that, where an audit is properly carried out, such clauses are always necessary to protect auditors’ interests.

In practice, the difference of opinion between the ICAEW and the ACCA may not be so great. If an ACCA auditor is not aware that a bank is going to place reliance on an audit report so no disclaimer is given , then it seems likely under Caparo or Bannerman that no duty of care would be owed to the bank in any event.

Settlements out of court

Legal cases may be settled out of court due to negotiation between the plaintiff and the defendent.

Benefits

Cost saving i.e. lower fees .

Time saving.

Less risk of damage to reputation.

Drawbacks

Does not address the importance of the practitioner’s legal responsibilities.

May be due to pressure from insurers, who are willing to risk a court settlement.

Insurance premiums may still rise.

Test your understanding

You are an audit manager in Ebony, a firm of Chartered Certified Accountants. Your specific responsibilities include planning the allocation of professional staff to audit assignments. The following matters have arisen in connection with the audits of three client companies:

- The finance director of Almond, a private limited company, has requested that only certain staff are to be included on the audit team

to prevent unnecessary disruption to Almond’s accounting department during the conduct of the audit. In particular, that Xavier be assigned as accountant in charge AIC of the audit and that no new trainees be included in the audit team. Xavier has been the AIC

for this client for the last two years. 5 marks

- Alex was one of the audit trainees assigned to the audit of Phantom, a private limited company, for the year ended 3 March Alex resigned from Ebony with effect from 30 November 0X4 to pursue a career in medicine. Kurt, another AIC, has just told you that on the

day Alex left he told Kurt that he had ticked schedules of audit work as having been performed when he had not actually carried out the

tests. 5 marks

- During the recent interim audit of Magenta, a private limited company, the AIC, Jamie, has discovered a material error in the prior year financial statements for the year ended 3 December These financial statements had disclosed an unquantifiable contingent liability for pending litigation. However, the matter was settled out of court for $4.5 million on 4 March 0X4. The auditor’s report on the financial statements for the year ended 3 December

0X3 was signed on 9 March 0X4. Jamie believes that Magenta’s management is not aware of the error and has not drawn it to their

attention. 5 marks

Required:

Comment on the ethical, quality control and other professional issues raised by each of the above matters and their implications, if any, for Ebony’s staff planning.

Note: The mark allocation is shown against each of the three issues.

Total: 5 marks

Test your understanding

The partner in charge of your audit firm has asked your advice on frauds which have been detected in recent audits.

- The audited financial statements of Lambley Trading were approved by the shareholders at the AGM on 3 June 0X . On 7 June 0X the managing director of Lambley Trading discovered a petty cash fraud by the cashier. Investigation of this fraud has revealed that it has been carried out over a period of a year. It involved the cashier making out, signing and claiming petty cash expenses which were charged to motor expenses. No receipts were attached to the petty cash vouchers. The managing director signs all cheques for reimbursing the petty cash float. Lambley Trading has sales of

$ million and the profit before tax is $ 50,000. The cashier has prepared the draft financial statements for audit.

The partner in charge of the audit decided that no audit work should be carried out on petty cash. He considered that petty cash expenditure was small, so the risk of a material error or fraud was small.

Required:

- Briefly state the auditor’s responsibilities for detecting fraud and error in financial statements.

- Consider whether your firm is negligent if the fraud amounted to $5,000.

- Consider whether your firm is negligent if the fraud amounted to

$ 0,000. 9 marks

- The audit of directors’ remuneration at Colwick Enterprises, a limited company, has confirmed that the managing director’s salary is $450,000, and that he is the highest paid director. However, a junior member of the audit team asked you to look at some purchase invoices paid by the company.

Your investigations have revealed that the managing director has had work amounting to $ 00,000 carried out on his home, which has been paid by Colwick Enterprises. The managing director has authorised payment of these invoices and there is no record of authorisation of this work in the board minutes.

The managing director has refused to include the $ 00,000 in his remuneration for the year, and to change the financial statements. If you insist on modifying your auditor’s report on this matter, the managing director says he will get a new firm to audit the current year’s financial statements. The company’s profit before tax for the year is $9 million.

Required:

Assuming the managing director owns 60% of the issued shares of

Colwick Enterprises and refuses to amend the financial statements:

- Consider whether the undisclosed remuneration is a material item in the financial statements.

- Describe the matters you will consider and the action you will take:

– to avoid being replaced as auditor, and

– if you are replaced as auditor.

- Describe the matters you will consider and the action you will take to avoid being replaced as auditor, assuming Colwick Enterprises is a listed company with an audit committee, and the managing director

owns less than % of the issued shares. marks

Total: 0 marks

Test your understanding 3

You are the auditor of Promise Co. The finance director has asked for a meeting with you. She recently discovered that the purchase ledger manager has diverted $50,000 of company funds into his own bank account. The FD has asked for an explanation as to why you did not highlight this issue during your recent audit. The profit for the year was $ 7.5 million.

Required

Explain the matters you should discuss with the FD at the meeting.

6 marks

Test your understanding 4

You are the auditor of a chain of restaurants. You have read a newspaper report that guests at a wedding have fallen ill after eating at one of your client’s restaurants.

Required

In relation to this report, describe the audit procedures you should

perform in respect of compliance with laws and regulations. 5 marks

Test your understanding 5

The directors of Jubilee Co have asked your firm to provide a detailed report at the end of the audit listing all the deficiencies in the internal control system. They are unhappy that during the year discounts had been given to customers who did not qualify for them. They have expressed dissatisfaction with your audit firm as this control deficiency was not reported to them by your firm.

Required

Draft points to include in your reply to Jubilee Co. 5 marks

Test your understanding 6

Set out the arguments for and against allowing auditors to agree a

contractual liability cap with clients. 6 marks

Test your understanding

The majority of marks will be awarded for application of knowledge to the scenario. Regurgitation of rote-learned facts will not score well. Therefore, in your answer refer to the situations, companies and individuals described in the question.

- Almond

There are many factors to be taken into account when allocating staff to an assignment, for example:

– the number of staff and levels of technical expertise required.

– logistics of time and place.

– the needs of staff e.g. for study leave .

– what is in the client’s best interest e.g. an expeditious audit .

A client should not dictate who staffs their audit. If the finance director’s requests are based solely on the premise that to have staff other than as requested would cause disruption then he should be assured that anyone assigned to the audit will be:

– technically competent to perform the tasks delegated to them.

– adequately briefed and supervised.

– mindful of the need not to cause unnecessary disruption.

Ebony may have other more complex assignments on which

Xavier and other staff previously involved in the audit of Almond could be better utilised.

To reassign Xavier to the job may be to deny him other on-the-job training necessary for his personal development. For example, he may be ready to assume a more demanding supervisory role with another client, or he may wish to expand the client base on which he works.

To keep Xavier with Almond for a third year may also increase the risk of familiarity with the client’s staff. Xavier may be too trusting of the client and lack professional scepticism.

If it is usual to assign new trainees to Almond then the finance director should be advised that to assign a higher grade of staff is likely to increase the audit fee as more experienced staff cannot necessarily do the work of more junior staff in any less time .

Conclusion

The finance director’s requests should be granted only if:

- it is in the interests of Almond’s shareholders primarily .

- meets the needs of Ebony’s staff.

- Almond agrees to the appropriate audit fee.

- Phantom

Ebony’s quality control procedures should be such that:

– the work delegated to Alex was within his capability.

– Alex was supervised in its execution.

– the work performed by Alex was reviewed by appropriate personnel i.e. someone of at least equal competence .

Alex’s working papers for the audit of Phantom should be reviewed again to confirm that there is evidence of his work having been properly directed, supervised and reviewed. If there is nothing which appears untoward it should be discussed with Alex’s supervisor on the assignment whether Alex’s confession to Kurt could have been a joke.

As Alex has already left not only the firm, but the profession, it may not seem worth the effort taking any disciplinary action against him e.g. reporting the alleged misconduct to ACCA . However, ACCA’s disciplinary committee would investigate such a matter and take appropriate action.

It is likely that Ebony will have given Alex’s new employer a reference. This should be reviewed in the light of any evidence which may cast doubt on Alex’s work ethics.

As there are doubts about the integrity of Alex, his work should now be reviewed again, to determine the risk that the conclusions drawn on his work may be unsubstantiated in terms of the relevance, reliability and sufficiency of audit evidence.

The review process should have identified the problem. If the reviewer did not detect an evident problem this would indicate the review process was not effective and the reviewer should be re trained as necessary.

The work undertaken by Alex for audit clients other than Phantom should also be subject to scrutiny.

Conclusion

As Kurt is already aware of the potential problem, it may be appropriate that he be assigned as AIC to audits on which Alex undertook audit work, as he will be alert to any ramifications. It is possible that Ebony should not want to make the situation known to its staff generally.

- Magenta

It appears that the subsequent events review was inadequate in that the impact of an adjusting event the out-of-court settlement was not considered.

The financial statements for the year ended 3 December 0X3 contained a material error in that they disclosed a contingent liability of unspecified amount when a provision should have been made.

The reasons for the error/oversight should be ascertained. For example:

– Who was responsible for signing off the subsequent events review?

– When was the review completed?

– For what reason, if any, was it not extended to the date of signing the auditor’s report?

– On what date was the written representation letter signed?

– Did the written representation letter cover the outcome of pending litigation?

The error has implications for the firm’s quality control procedures. For example:

– Was the AIC adequately directed and supervised in the completion of the subsequent events review?

– Was the work of the AIC adequately reviewed, to notice that it was not extended up until the date on which the auditor’s report was signed?

Ebony may need to review and improve on its procedures for the audit of provisions, contingent liabilities and subsequent events.

If the AIC or other staff involved in the prior year audit of Magenta was not as thorough as they should have been with respect to the subsequent events review, then other audit clients may be similarly affected.

The auditor has a duty of care to draw the error/oversight to Magenta’s attention. This would be an admission of fault for which Ebony should be liable if Magenta decided to take action against the firm.

If Ebony remains silent and in the hope the error is unnoticed, there is the risk that Magenta will find out anyway.

As the matter is material, it warrants a prior period adjustment IAS® Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors . If this is not made, the financial statements will be materially misstated with respect to the current year and comparatives because the expense of the out-of-court settlement should be attributed to the prior period and not the current year’s profit or loss.

The most obvious implication for the current year audit of Magenta is that a more thorough subsequent event review will be required than the previous year. This may have a consequent effect on the time/fee/staff budgets of Magenta for the year ended 3 December 0X4.

As the matter is material, it needs to be brought to the attention of Magenta’s management, so that a prior year adjustment is made. If an adjustment is not made a modified opinion qualified – ‘except for’ will be required.

Conclusion

The staffing of the final audit of Magenta should be reviewed and perhaps a more experienced person assigned to the subsequent event review than in the prior year. The assignments allocated to the staff responsible for the oversight in Magenta’s prior period should be reviewed and their competence/capability re-assessed.

Test your understanding

There are three main aspects of auditing examined in this question:

The role of, and potential liability of, the auditor in connection with the detection and prevention of fraud

The concept of materiality

The position of the auditor when threatened with dismissal and replacement.

Note: Misstatements of > 5% profit before tax and > ½ % revenue are considered material.

- Lambley Trading

- Auditors should design their audit procedures to have a reasonable expectation of detecting material fraud and error in the financial statements.

An auditor would generally be considered to be at fault if he fails to detect material fraud and error. However, the auditor may not be liable if the fraud is difficult to detect because the fraud had been concealed.

A claim for negligence against the auditor for not detecting immaterial fraud or error would be unsuccessful, except in the circumstances described below.

An auditor may be negligent if he:

– Finds an immaterial fraud while carrying out his normal procedures and does not report it to the company’s management. However, he may not be negligent if the evidence to support a suspected fraud is weak.

– Carries out audit procedures on immaterial items, of which the company’s management is aware, and these procedures are not carried out satisfactorily, so failing to detect an immaterial fraud. For instance, there may be a teeming and lading fraud, and the auditor may check receipts from sales are correctly recorded in the cash book and sales ledger, but fail to check that the cash from these sales is banked promptly.

– Carries out audit procedures on immaterial items at the specific request of the company’s management, and the auditor failed to detect an immaterial fraud due to negligent work. The management would have a good case to claim damages for negligence against the auditor.

- A fraud of $5,000 is 3.3% of the company’s profit before tax, so it is immaterial.

As the auditor has carried out no work in this area, and is not responsible for detecting immaterial fraud, it is probable that he is not negligent.

It could be argued that the other audit procedures should have detected an apparent irregularity, such as analytical procedures. This might have indicated an increase in motor expenses compared with the previous year and budget, or the auditor could have looked at petty cash expenditure, which would show an increase compared with the previous year.

It could also be argued that the auditor should have looked at the absolute level of petty cash expenditure in order to decide whether to carry out work on the petty cash system. These arguments against the auditor are relatively weak, and it is unlikely that a claim for negligence would be successful. However, not detecting the fraud is likely to lead to a deterioration of the client’s confidence in the auditor.

- A fraud of $ 0,000 is 3% of the company’s profit before tax, so it is material. It appears that the auditor may have been negligent in not carrying out any audit work on petty cash.

The auditor should design audit procedures so as to have a reasonable expectation of detecting material fraud or error. As no work was performed on petty cash there is no chance of detecting the fraud.

As a minimum, the auditor should have looked at the level of petty cash expenditure, comparing it with the previous year and the budget. This should have highlighted the increase in expenditure and led to the auditor carrying out further investigations.

As this is a petty cash fraud, it could be difficult to detect, but the cashier writing out and signing the petty cash vouchers, with no receipt attached, should have led the auditor to suspect the fraud.

It could be argued that the company has some responsibility for allowing the fraud to take place, as there was a serious deficiency in the system of internal control i.e. the cashier recorded and made petty cash payments, and appeared to be able to authorise petty cash vouchers .

A more senior employee e.g. the managing director should have checked the cashier’s work. Also, the managing director would have signed cheques which reimburse the petty cash, and he should have been aware that these had increased and investigated the reasons for the increase.

- Colwick Enterprises

- In terms of profit before tax, the sum of $ 00,000 is immaterial. Normally, a material item in terms of profit before tax is a misstatement which exceeds 5% of the profit before tax

i.e. $4.55 million , so $ 00,000 is very small.

However, in terms of the director’s remuneration, the $ 00,000 is 44% of the managing director’s annual salary of $450,000.

Directors’ remuneration is an important item in the financial statements, both as far as legal requirements are concerned, and to the users of the financial statements, therefore is material by nature.

The company is proposing that the financial statements should show only 69% of the managing director’s remuneration, so the understatement is material.

- If the managing director refused to change the financial statements, the auditor’s opinion should be qualified and the basis for qualified opinion should state his total emoluments are $650,000.

However, it seems probable that he will try to dismiss the audit firm before they issue their auditor’s report on the financial statements. In order to change the auditor, he must:

– Find another auditor who is prepared to accept appointment as auditor, and

– Call a general meeting to vote on the change of auditor, and

– Notify the shareholders, the new auditor, and the existing auditor.

The auditor has the right to make representations to the shareholders, which can either be sent to the shareholders before the meeting, and/or make the representations at the meeting when the replacement of the auditor is proposed.

Although these representations are likely to have little effect on the change of auditor as the managing director owns 60% of the shares, and only a majority vote is required to change the auditor , it would alert the other shareholders to the action of the managing director and concealment of information.

As a further point, provided the new auditors are a member of the ACCA or one of the recognised bodies, the Code of Ethics requires the new auditor to contact the outgoing auditor asking if there are any matters to be brought to their attention to enable them to decide whether or not they are prepared to accept the audit appointment. The outgoing auditor should reply to their letter promptly, saying that the managing director has had $ 00,000 of benefits-in-kind, which he refuses to allow to be disclosed in the financial statements.

It has been explained to the managing director that the auditor’s opinion will be qualified if these emoluments are not disclosed and this is the reason why he is proposing replacement of the auditor. If the proposed new auditors have the expected amount of integrity, they should discuss this point with the managing director, and point out that they will have to qualify the opinion if the benefits of $ 00,000 are not included in his remuneration in the financial statements.

If the new auditors take over the appointment and give an unmodified report, the outgoing auditor should take legal advice. The action taken would include:

– Disclosing information about the director’s remuneration to the new auditor’s professional body, and the fact that the auditor’s report has not been modified.

– Disclosing the benefit to the tax authorities as it may not have been subject to income tax .

- If the managing director owned less than % of the issued shares, the auditor’s position would be much stronger than in part ii If the managing director refuses to increase the remuneration in the draft accounts, the matter should be referred to the audit committee.

If he still refuses to change the remuneration, a meeting with the members should be arranged with the chairman of the audit committee. The auditor would explain that the opinion will be qualified unless the remuneration was increased to $650,000.

However if the audit committee believes the financial statements should not be changed, the auditor’s report will need to be modified. If, at this stage, the directors decide to replace the audit firm, they will have to call a general meeting for this purpose. Representations should be made in writing to the shareholders, and/or circulated at the general meeting.

As Colwick Enterprises is a listed company, this information is likely to be picked up by the press and financial institutions, and result in adverse publicity for the company. It is likely to make shareholders suspicious of the integrity of the managing director and the other directors.

In addition, it is likely that either the company or the managing director is committing an offence by not disclosing this benefit to the tax authorities.

Test your understanding 3

Notes for meeting with finance director

Engagement letter:

– Refer to any specific points regarding work in this area.

– Refer to section on auditor’s and directors’ responsibilities.

– Client signed the engagement letter agreeing to the terms.

Responsibility for detection of fraud is primarily the responsibility of management.

Implementation of an internal control system is the responsibility of management.

The auditor’s role is to obtain reasonable assurance that financial statements are free from material fraud and error.

The amounts in question are not material, only 0.3% PBT.

Ascertain how the FD discovered the fraud.

Ascertain how the amounts of diverted funds were quantified. Discuss whether there might be further unidentified sums.

Test your understanding 4

The auditor should consider whether there has been a breach of laws or regulations, for example laws and regulations over health and safety, food hygiene, product use by dates etc.

Procedures include:

Obtain a general understanding of the relevant legal and regulatory framework by:

– Researching the industry on the internet

– Considering laws and regulations applicable to other clients in the same industry

– Enquiring of management.

Discuss with the directors and other appropriate management whether there have been any instances of non-compliance.

Inspect correspondence with the local authority and hygiene inspectors regarding instances of non-compliance.

Evaluate the financial impact of the non-compliance, for example, possible penalties, cost of compensation claims, cost of remedial action, and impact on the value of the brand name.

Obtain written representations from management that they have provided the auditor with all information in relation to the non-compliance and its impact.

Consult experts in the area if considered necessary.

Test your understanding 5

Auditors must determine the most effective approach to each area of the financial statements. This may involve a combination of tests of controls and substantive procedures, or substantive procedures only.

Where the auditors choose to test the internal control systems of the company, they must design their work to have a reasonable expectation of detecting any deficiencies which would be likely to result in a material misstatement in the financial statements.

The area of discounts may have been one which did not involve testing of the internal controls as analytical procedures are likely to be effective.

Even if the controls in this area have been tested, the discounts given to customers may have been recorded accurately in the financial statements. In this case no material misstatement has occurred.

Jubilee must be reminded that the control deficiencies included in the report to management is simply a by-product of the audit. It is not intended to be a comprehensive list of all possible deficiencies. Should Jubilee Co require a more comprehensive review, then this could be undertaken as a separate assurance assignment.

Test your understanding 6

For

Avoids firms exiting from the statutory audit market and thus maintaining choice and competition.

Clearly quantifies the extent of auditors’ liability to the public. Reduces the risk of auditors being used as scapegoats.

Ensures that directors bear their extent of liability.

Against

Auditors may not feel as accountable or be seen to be as accountable.

May reduce the perceived value of an audit if risk to auditors is reduced.

Setting a cap may be a difficult and contentious issue to agree with the client.

Shareholders or other parties to whom the auditors owe a duty of care may find themselves inadequately protected.