18 Personal effectiveness and communication

This chapter draws together a number of topics that relate to

the way that people do their jobs.

Section 1 covers time management, a very necessary skill for

all busy people. Good time management depends to some

extent on ruthless prioritisation and this requires a good

understanding by staff of just what their roles are. The role of

information technology in improving personal effectiveness is

discussed in Section 2.

In Section 3, we look at the consequences of ineffectiveness

at work.

Section 4 covers competence frameworks, and coaching,

mentoring and counselling as tools in personal development.

We also focus on personal development plans, which are

valuable for setting out the activities to ensure development

and improved job performance.

Section 5 looks at conflict and the techniques for resolving it.

The rest of this chapter (Sections 6 to 10) is principally

concerned with communication. Communication is

fundamental to the success of any organisation of any size,

since it is only via communication that we know what is to be

done, by whom and how. Communication is also fundamental

to motivation, as you discovered in Chapter 15.

| Study Guide | Intellectual level |

|

|

| E1 Personal effectiveness techniques

(a) Explain the importance of effective time management. |

K |

||

| (b) Describe the barriers to effective time management and how they may be overcome. | K | ||

| (c) Describe the role of information technology in improving personal effectiveness. | S | ||

| E2 Consequences of ineffectiveness at work

(a) Identify the main ways in which people and teams can be ineffective at work. |

S |

|

|

| (b) Explain how individual or team ineffectiveness can affect organisational performance. | K | ||

| E3 Competence frameworks and personal development (a) Describe the features of a ‘competence framework’. | S |

|

|

| (b) Explain how a competence framework underpins professional development needs. | S | ||

| (c) Explain how personal and continuous professional development can increase personal effectiveness at work. | S | ||

| (d) Explain the purpose and benefits of coaching, mentoring and counselling in promoting employee effectiveness. | K | ||

| (e) Describe how a personal development plan should be formulated, implemented, monitored and reviewed by the individual. | S | ||

| E4 Sources of conflict and techniques for conflict resolution and referral

(a) Identify situations where conflict at work can arise. |

S |

|

|

| (b) Describe how conflict can affect personal and organisational performance. | S | ||

| (c) Identify ways in which conflict can be managed. | S | ||

| E5 Communicating in business (a) Describe methods of communication used in the organisation and how they are used. |

K |

|

|

| (b) Explain how the type of information differs and the purposes for which it is applied at different levels of the organisation: strategic, tactical and operational. | K | ||

| (c) List the attributes of good quality information. | K | ||

| (d) Explain a simple communication model: sender, message, receiver, feedback, noise. | K | ||

| (e) Explain formal and informal communication and their importance in the workplace. | K | ||

| (f) Identify the consequences of ineffective communication. | K | ||

| (g) Describe the attributes of effective communication. | K | ||

| (h) Describe the barriers to effective communication and identify practical steps that may be taken to overcome them. | K | ||

| (i) Identify the main patterns of communication. | K | ||

| 1 | Time management | |||

| Time is a scarce resource and managers’ time must be used to best effect. Urgency and importance must be recognised and distinguished. Tasks must be prioritised and scheduled. In-trays can be managed using the ABCD method. Other important matters are correct use of the telephone, availability to callers and seeing tasks through to completion. | ||||

The scarcest resource any of us has is time. No amount of investment can add more hours to the day or weeks to the year. All we can do is take steps to make more effective use of the time which is available to us. Planning how we spend our time is as normal to us as planning how we will spend our income, and you should already have considerable experience of both.

To be worth their pay, every employee needs to add more value than they cost per hour. If you do the same exercise for the whole team, you can see how expensive the time of your section actually is, and why keeping colleagues waiting to start a meeting or training course is more serious than just a breach of manners. It is important, therefore, that managers work as efficiently as possible.

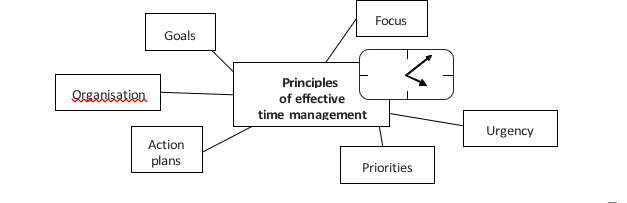

| Effective time management involves attention to:

• Goal or target setting Focus •Action planning Urgency • Prioritising Organisation |

Time management tasks

- Identifying objectives: and the key tasks which are most relevant to achieving them – sorting out what the supervisor must do, from what he could do, and from what he would like to do. Urgent is not always the same as important.

1.1 Principles of time managementPrioritising and scheduling: assessing key tasks for relative importance and amount of time required. Routine non-essential tasks should be delegated – or done away with if possible. Routine key tasks should be organised as standard procedures and systems. Non-routine key tasks will have to be carefully scheduled as they arise, according to their urgency and importance; an up-to-date diary with a carry forward system to follow-up action will be helpful.

- Planning and control: Schedules should be regularly checked for disruption by the unexpected; priorities will indicate which areas may have to be set aside for more urgent items. Information and control systems in the organisation should be utilised so that problems can be anticipated, and sudden decisions can be made on the basis of readily available information.

The key principles of time management can be depicted as follows.

1.1.1 Goals

If you have no idea what it is you are supposed to accomplish, all the time in the world will not be long enough to get it done. Nor is there any way of telling whether you have done it or not. To be useful, goals need to be SMART:

Specific

Measureable

Attainable

Realistic Time-bounded

1.1.2 Action plans

Now you must make written action plans that set out how you intend to achieve your goals.

1.1.3 Priorities

Now you can set priorities from your plan. You do this by deciding which tasks are the most important: what is the most valuable use of your time at that very moment?

Focus: one thing at a time

Work on one thing at a time until it is finished, where possible.

1.1.4 Urgency: do it now!

Do not put off large, difficult or unpleasant tasks simply because they are large, difficult or unpleasant.

1.1.5 Organisation

Apart from working to plans, checklists and schedules, your work organisation might be improved by the following.

- An ABCD method of in-tray management. Resolve to take one of the following approaches.

Act on the item immediately

Bin it, if you are sure it is worthless, irrelevant and unnecessary

Create a definite plan for coming back to the item: get it on your schedule, timetable or ‘to do list’

Delegate it to someone else to handle

- Organise your work in batches. Batches should contain jobs requiring the same activities, files, equipment, and so on.

- Take advantage of your natural work patterns. Self-discipline is aided by developing regular hours or days for certain tasks, like dealing with correspondence first thing, or filing at the end of the day.

- Improving time management

Plan each day. The daily list should include the most important tasks as well as urgent but less important tasks.

Produce a longer-term plan. This can highlight the important tasks so that sufficient time is spent on them on a daily basis.

Do not be available to everyone at all times. Constant interruptions can be prevented by, for example, setting ‘surgery hours’ during which your door is open to visitors.

Stay in control of the telephone. For example, only take calls during certain times and divert calls to your secretary during the rest of the day.

- Prioritisation

| Prioritising tasks involves ordering tasks in order of preference or priority, based on:

• The relative consequences of timely or untimely performance • Importance • Dependency of other people on completion of the task(s) • Urgency • Defined deadlines, timescales and commitments |

Prioritisation involves identifying key results (objectives which must be achieved if the section is to fulfil its aims) and key tasks (those things that must be done on time and to the required standard if the key results are to be achieved).

A job will be important compared with other tasks if it satisfies at least one of three conditions.

- One of the problems managers have in allocating their time comes from determining which tasks are important as defined above and distinguishing these from urgent tasks, which may have a deadline but less importance.It adds value to the organisation’s output.

- It comes from a source deserving high priority, such as a customer or senior manager.

- The potential consequences of failure are long term, difficult to reverse, far reaching and costly.

- Tasks both urgent and important should be dealt with now, and given a fair amount of time.

- Tasks not urgent but still important will become urgent as the deadline looms closer. Some of these tasks can be delegated.

- Tasks urgent but not important should be delegated, or designed out of your job. The task might be urgent to someone else, but not to you.

- Tasks neither urgent nor important should be delegated or binned.

Performance objective PO5 of your Practical Experience Requirements requires you to be able to manage yourself effectively. You can apply the knowledge that you learn from this section on time management to help you demonstrate this competence.

1.4 Work planning

| Work planning includes the following basic steps.

• Establishing priorities • Loading, allocation of tasks • Sequencing of tasks • Scheduling: estimating the time taken to complete a task and working forwards or backwards to determine start or finish times |

| Planning activity | Example |

| Scheduling routine tasks so that they will be completed at pre-determined times | You plan to complete bank reconciliations every month. |

| Handling high-priority tasks and deadlines:

working into the routine any urgent tasks which interrupt the usual level of working |

You adjust your plans so that you can prepare an urgent costing requested by the sales manager. |

| Adapting to changes and unexpected demands | A colleague may go off sick: there should be a contingency plan to enable to you to provide cover for them. |

| Setting standards against which performance will be measured | You set a target to complete a certain number of costings to a certain level of accuracy. |

| Co-ordinating your own plans and efforts with those of others | You plan to get your costings to the sales meeting in time for sales staff to prepare a quote for a client. |

Work planning, as the term implies, means planning how, when and by whom work should be done, so that objectives can be efficiently met. At an individual level, this may involve the following.

Work planning consists of a number of basic steps.

- Allocating work to people and machines (sometimes called loading)

- Determining the order in which activities are performed (prioritising: sometimes called activity scheduling or task sequencing)

- Determining exactly when each activity will be performed (timetabling: sometimes called time scheduling)

- Establishing checks and controls to ensure that deadlines are being met and that routine tasks are still achieving their objectives

| 2 | The role of information technology |

In this section we discuss some of the most significant developments in communication technology, and the impact these developments have had on the way people do their work.

Digital means ‘of digits or numbers’. Digital information is information in a coded (binary) form.

Information in analogue form uses continuously variable signals.

- Modems and digital transmission

New technologies require transmission systems capable of delivering substantial quantities of data at great speed.

- Mobile communications

Networks for portable telephone communications, also known as ‘cellular‘ or ‘mobile phones‘, have boomed in developed countries since the 1990s.

Digital networks have been developed which are better able to support data transmission than the older analogue networks, with higher transmission speeds and less likelihood of data corruption.

- Voice messaging systems

Voice messaging systems answer and route telephone calls. Typically, when a call is answered a recorded message tells the caller to dial the extension required, or to hold if they want to speak to the operator.

- A computer bulletin board consists of a central mailbox or area on a computer server where people can deposit messages for everyone to see and, in turn, read what other people have left in the system.Computer bulletin boards

Bulletin boards can be appropriate for a team of individuals at different locations to compare notes. It becomes a way of keeping track of progress on a project between routine team meetings.

2.5 Videoconferencing

Videoconferencing is the use of computer and communications technology to conduct meetings.

Videoconferencing has become increasingly common as the internet and webcams have brought the service to desktop PCs at reasonable cost. More expensive systems feature a separate room with several video screens, which show the images of those participating in a meeting.

2.6 Electronic Data Interchange (EDI)

EDI is a form of computer-to-computer data interchange. Instead of sending each other reams of paper in the form of invoices, statements, and so on, details of inter-company transactions are sent via telecoms links, avoiding the need for output and paper at the sending end, and for re-keying of data at the receiving end.

2.7 Deciding on a communication tool

| The channel of communication will impact on the effectiveness of the communication process. The characteristics of the message will determine what communication tool is best for a given situation. |

Technological advances have increased the number of communication tools available. The features and limitations of ten common tools are outlined in the following table.

| Tool | Features/Advantages | Limitations |

| Conversation | Requires little or no planning | May be easily forgotten |

| Meeting | Allows multiple opinions to be expressed | Can highlight differences and become time-wasting confrontations |

| Presentation | Visual aids such as slides can help the communication process | Requires planning and skill |

| Telephone | Good for communications that do not require (or you would prefer not to have) a permanent written record | No written record gives greater opportunity for misunderstandings |

| Facsimile | Enables reports and messages to reach remote locations quickly | Complex images do not transmit well |

| Memorandum | Provides a permanent record | Can come across as impersonal |

| Letter | Provides a permanent record of an external message Adds formality to external communications |

If inaccurate or poorly presented provides a permanent record of incompetence

May be slow to arrive depending on distance and the postal service |

| Report | Provides a permanent, often comprehensive written record | Complex messages may be misunderstood in the absence of immediate feedback |

| Provides a written record

Attachments (eg reports or other documents) can be included Quick – regardless of location Can be sent to multiple recipients easily, can be forwarded on to others |

Long messages (more than one ‘screen’) may best be dealt with via other means, or as attached documents | |

| Videoconference | This is in effect a meeting conducted using a computer and video system Some non-verbal messages (eg gestures) will be received |

Image quality is often poor – resulting in not much more than an expensive telephone conference call! |

2.8 The effect of office automation on business

Office automation has an enormous effect on business. We discuss some of the most significant effects in this section.

2.8.1 Routine processing

The processing of routine data can be done in bigger volumes, at greater speed and with greater accuracy than with non-automated, manual systems.

2.8.2 The paperless office

There might be less paper in the office (but not necessarily so) with more data processing done using computers. Many organisations print information held in computer files resulting in more paper in the office than with manual systems!

2.8.3 Management information

The nature and quality of management information has changed.

- Managers are likely to have access to more information – for example from a database. Information is also likely to be more accurate, reliable and up to date. The range of management reports is likely to be wider and their content more comprehensive.

- Planning activities should be more thorough, with the use of models (eg spreadsheets for budgeting) and sensitivity analysis.

- Information for control should be more readily available. For example, a computerised sales ledger system should provide prompt reminder letters for late payers, and might incorporate other credit control routines. Stock systems, especially for companies with stocks distributed around several different warehouses, should provide better stock control.

- Decision-making by managers can be helped by decision support systems.

2.8.4 Organisation structure

The organisation structure might change. PC networks give local office managers a means of setting up a good local management information system, and localised data processing while retaining access to centrally held databases and programs. Office automation can therefore encourage a tendency towards decentralisation of authority within an organisation.

On the other hand, such systems help head office to keep in touch with what is going on in local offices. Head office can therefore readily monitor and control the activities of individual departments, and retain a co-ordinating influence.

2.8.5 Customer service

Office automation, in some organisations, results in better customer service. When an organisation receives large numbers of telephone enquiries from customers, the staff who take the calls should be able to provide a prompt and helpful service if they have online access to the organisation’s data files.

2.8.6 Homeworking or remote working

Advances in communications technology have, for some tasks, reduced the need for the actual presence of an individual in the office.

The advantages to the organisation of homeworking are as follows.

- Cost savings on space. Office rental costs and other charges can be very expensive. If firms can move some of their employees on to a homeworking basis, money can be saved.

- A larger pool of labour. The possibility of working at home might attract more applicants for clerical positions, especially from people who have other demands on their time (eg going to and from school) which cannot be fitted round standard office hours.

- If the homeworkers are freelance, then the organisation avoids the need to pay them when there is insufficient work, when they are sick, on holiday, etc.

Performance objective PO5 of your Practical Experience Requirements requires you to be able to ’work with others to recognise, assess and improve business performance. You use different techniques and technology to do this’. You can apply the knowledge that you learn from this section on the role of information technology to help you demonstrate this competence.

2.9 How technology can enhance personal effectiveness

2.9.1 Intranet

Many organisations use their intranets to deliver training modules eg ethics, work and safety procedures. Studying and assessment is carried out online, enabling employees to get immediate results as part of their ongoing learning and development.

2.9.2 Proprietary systems

Examples include:

- Skype – using your PC to telephone with video link, also useful for video conferencing

- Webex – web conferencing, online meetings and events

| 3 | Ineffectiveness at work |

3.1 The main ways in which employees can be ineffective

- Failing to communicate (eg problems, delays)

- Failing to meet deadlines

- Failing to comply with job specifications Failing to deliver the exact product needed

3.2 Effects on the organisation

- Potential problems are not identified and so no countermeasures can be taken in time to prevent the problem arising

- Problems are not dealt with as they arise

- Deadlines are not met

- Customers are angry and go elsewhere

| 4 | Competence frameworks and personal development |

4.1 Competence frameworks

A competence framework sets out what an employee should be able to do and what the employee ought to know.

An employee’s job description should include a competence framework and the employee should be encouraged to keep up to date with developments in their field. This may involve regular attendance at conferences and update courses as part of the employee’s professional development. Having a defined set of competences that are necessary for a job should help an organisation in the following ways.

- Assisting effective recruitment

- As a tool for performance evaluation

- Identifying skills gaps and planning training accordingly

4.1.1 Advantages of competence frameworks

Evaluating an individual’s performance on the basis of what they can actually do is fairer than judging them on their personal qualities, qualifications or the amount of time spent on activities, providing a foundation for more objective performance reviews.

The framework also provides a basis for employees to plan their personal development.

www.ACCAGlobalBox.com

4.1.2 Disadvantages of competence frameworks

Competency frameworks are hard to develop. They require a clear understanding of the job and a focus to think in terms of what employees need to be able to do rather than what they need to be.

Competences can be expressed at such a generic level (‘innovativeness’, ‘leadership’) that they become meaningless and difficult to measure.

4.2 Coaching

Coaching is an approach whereby a trainee is put under the guidance of an experienced employee who shows the trainee how to perform tasks. It is also a fashionable aspect of leadership style and a feature of superior/subordinate relationships, where the aim is to develop people by providing challenging opportunities and guidance in tackling them.

| Step 1 | Establish learning targets. The areas to be learnt should be identified, and specific, realistic goals (eg completion dates, performance standards) stated by agreement with the trainee. |

| Step 2 | Plan a systematic learning and development programme. This will ensure regular progress, appropriate stages for consolidation and practice. |

| Step 3 | Identify opportunities for broadening the trainee’s knowledge and experience, eg by involvement in new projects, placement on interdepartmental committees, suggesting new contacts, or simply extending the job, adding more tasks, greater responsibility, etc. |

| Step 4 | Take into account the strengths and limitations of the trainee in learning, and take advantage of learning opportunities that suit the trainee’s ability, preferred style and goals. |

| Step 5 | Exchange feedback. The coach will want to know how the trainee sees their progress and future. They will also need performance information in order to monitor the trainee’s progress, adjust the learning programme if necessary, identify further needs which may emerge and plan future development for the trainee. |

Note that coaching focuses on achieving specific objectives.

3 Mentoring

Mentoring is a long-term relationship in which a more experienced person acts as a teacher, counsellor, role model, supporter and encourager to another person with the aim of fostering the individual’s personal and career development.

Mentoring differs from coaching in two main ways.

- The mentor is not usually the protégé’s immediate superior.

- Mentoring covers a wide range of functions, not always related to current job performance.

Career functions include:

- Sponsoring within the organisation and providing exposure at higher levels Coaching and influencing progress through appointments

- Protection

- Drawing up personal development plans

- Advice with administrative problems that people face in their new jobs Help in tackling projects by pointing people in the right direction Psychosocial functions include:

- Creating a sense of acceptance and belonging

- Counselling and friendship Providing a role model

Organisational arrangements for coaching and mentoring will vary, but in general a coach needs to be an expert in the trainee’s professional field. Mentors are often drawn from other areas of the organisation but can open up lines of communication to those with power and influence across it. For this reason, a mentor is usually in a senior position.

4.4 Counselling

| Counselling is an interpersonal interview, the aim of which is to facilitate another person in identifying and working through a problem. |

The need for workplace counselling can arise in many different situations.

- Note that counselling is non-directive. The individual decides what is to be achieved and how. Counselling helps people to help themselves.During appraisal, to solve work or performance problems

- In grievance or disciplinary situations

- Following change, such as promotion or relocation

- On redundancy or dismissal

- As a result of domestic or personal difficulties

- In cases of sexual, racial or religious harassment or bullying at work (to support the victim and educate the perpetrator)

4.5 Benefits of counselling

Effective counselling is not merely a matter of pastoral care for individuals, but is very much in the organisation’s interests. Counselling can:

- Prevent underperformance, reduce labour turnover and absenteeism and increase commitment from employees

- Demonstrate an organisation’s commitment to and concern for its employees

- Give employees the confidence and encouragement necessary to take responsibility for self and career development

- Recognise that the organisation may be contributing to the employees’ problems and provide an opportunity to reassess organisational policy and practice

- Support the organisation in complying with its obligations (eg in regard to managing harassment in the workplace).

www.ACCAGlobalBox.com

4.6 The counselling process

| Counselling is facilitating others through the process of defining and exploring their own problems: it is primarily a non-directive role. |

Managers may be called on to use their expertise to help others make informed decisions or solve problems by:

- The counselling process has three broad stages (Egan, 2014).Advising: offering information and recommendations on the best course of action. This is a relatively directive role, and may be called for in areas where you can make a key contribution to the quality of the decision: advising an employee about the best available training methods, say, or about behaviour which is considered inappropriate in the workplace.

- Counselling: facilitating others through the process of defining and exploring their own problems and coming up with their own solutions. This is a relatively non-directive role, and may be called for in areas where you can make a key contribution to the ownership of the decision: helping employees to formulate learning goals, for example, or to cope with work (and sometimes nonwork) problems.

| Step 1 | Reviewing the current scenario: helping people to identify, explore and clarify their problem situations and unused opportunities. This is done mostly by listening, encouraging them to tell their ‘story’, and questioning/probing to help them to see things more clearly. |

| Step 2 | Developing a preferred scenario: helping people to identify what they want, in terms of clear goals and objectives. This is done mostly by encouraging them to envisage their desired outcome, and what it will mean for them (in order to motivate them to make the necessary changes). |

| Step 3 | Determining how to get there: helping people to develop action strategies for accomplishing goals, for getting what they want. This is done mostly by encouraging them to explore options and available resources, select the best option and plan their next steps. |

- Confidentiality

There will be situations when an employee cannot be completely open unless they are sure that any comments will be treated confidentially. However, certain information, once obtained by the organisation (for example about fraud or sexual harassment) calls for action. In spite of the drawbacks, employees must be made aware when their comments will be passed on to the relevant authority, and when they will be treated completely confidentially.

- Personal development plans and objectives

- A personal development plan is a clear developmental action plan for an individual which incorporates a wide set of developmental opportunities, including formal training.

- Self development may be defined as: ‘personal development, with the person taking primary responsibility for his or her own learning and for choosing the means to achieve this.’ (Pedler, et al, 1991)

Personal development implies a wide range of activities with the objectives of:

- Improving performance in an existing job

- Improving skills and competences, perhaps in readiness for career development or organisational change

- Planning experience and pathways for career development and/or advancement within the organisation

- Acquiring transferable skills and competences for general ’employability’ or change of direction

- Pursuing personal growth towards the fulfilment of one’s personal interests and potential

4.9 A systematic approach to personal development planning

A systematic approach to planning your own development will include the following steps.

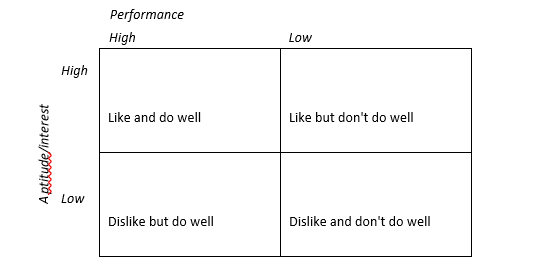

| Step 1 | Select an area for development: a limitation to overcome or a strength to build on. Your goals might be based on your need to improve performance in your current job and/or on your career goals, taking into account possible changes in your current role and opportunities within and outside the organisation. You might carry out a personal SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis. One helpful tool is an interest/ aptitude and performance matrix, on which you can identify skills which you require (don’t do well) but for which you can build on your aptitudes and interests (like). |

| Step 2 | Set a SMART (specific, measurable, agreed, realistic and time-bounded) learning objective: what you want to be able to do or do better, and in what timescale. |

| Step 3 | Determine how you will move towards your objective:

• Research relevant learning resources and opportunities • Evaluate relevant learning resources and opportunities for suitability, attainability and cost effectiveness • Secure any support or authorisation required from your manager or training development |

| Step 4 | Formulate a comprehensive and specific action plan, including: • The SMART objective • The learning approaches you will use, described as specific actions to take. (Ask a colleague to provide feedback; watch a training video; enrol in a course.) Each action should have a realistic timescale or schedule for completion. • A monitoring and review plan. Precisely how and when (or how often) will you assess your progress and performance against your objectives? (Seek feedback? review results? pass an end of course test?) |

| Step 5 | Secure agreement to your action plan (if required to mobilise organisational support or resources). |

| Step 6 | Implement your action plan. |

Make sure you don’t neglect your study and revision in what may appear to be ‘soft’ syllabus topics, such as the preparation of a PDP.

Part of performance objective PO3 of your Practical Experience Requirement on strategy and innovation indicates that you should ‘plan, identify and monitor appropriate personal targets and standards of delivery so that they meet the wider departmental and strategic objectives of your organisation’. You can apply the knowledge that you have learnt from this section to help fulfil this requirement.

| 5 | Conflict | |||

| Key approaches to managing disagreements and conflicts include understanding the problem and the personalities involved; encouraging those involved to discuss the problem; exploring possibilities for mutual satisfaction (win-win); negotiating compromise where required; using formal grievance procedures where necessary. | ||||

5.1 How does conflict arise?

Conflict is the clash of opposing ‘forces’, including the personalities, interests, opinions or beliefs of individuals and groups. Conflict often arises within and between teams because of a number of factors.

- Power and resources are limited (and sometimes scarce) in the organisation. Individuals and groups compete for them, fearing that the more someone else has, the less there is to go around.

- Individuals and teams have their own goals, interests and priorities – which may be incompatible.

- There may be differences and incompatibilities of personality between individuals, resulting in ‘clashes’.

- There may be differences and incompatibilities of work methods, timescales and working style, so that individuals or teams frustrate each other with apparent lack of co-ordination (especially if one person’s task depends on the other’s).

Difference and competition by themselves do not lead directly to conflict: they can even be positive forces, helping people to solve problems or to lift their performance.

However, they can escalate or deteriorate into destructive conflict if:

- There is poor or limited communication: assumptions go unchallenged, misunderstandings go unclarified, and feelings are left undealt with.

QUESTION ConflictThere is poor co-ordination: working relationships are not managed or structured, and so are subject to interpersonal problems or unchecked competition.

- There are status barriers: problems in the relationship are glossed over by the superior asserting authority (‘do it because I said so’), or hidden by the subordinate feeling powerless or threatened (‘it’s more than my job’s worth to say anything’).

- Work demands put pressure on individuals and teams: competition may escalate, feelings may become less manageable under stress, and there may be little time allowed for interpersonal problem-solving.

Suggest how conflict may be (a) positive or constructive and (b) negative or destructive.

ANSWER

Conflict is constructive, when its effect is to:

- Introduce different solutions to problems

- Define power relationships more clearly

- Encourage creativity, the testing of ideas

- Focus attention on individual contributions

- Bring emotions out into the open

- Release of hostile feelings that have been, or may be, repressed otherwise

Conflict is destructive when its effect is to:

- Distract attention from the task

- Polarise views and ‘dislocate’ the group

- Subvert objectives in favour of secondary goals

- Encourage defensive or ‘spoiling’ behaviour

- Force the group to disintegrate (f) Stimulate emotional, win-lose conflicts, ie hostility

5.2 Managing your own interpersonal conflicts

Performance objective PO2, covering stakeholder relationship management, mentions as an example demonstrating how you are able to discuss work problems or issues with colleagues or clients to improve or maintain relationships. If you have experienced any problems or conflicts while working with someone, you might attempt some of the methods discussed here..

Conflicts and sources of dissatisfaction can be managed informally in several ways.

- Communicate

The first step in any conflict or difficulty should be direct, informal discussion with the person concerned.

- Where there is a personality or style clash, this gets the problem out in the open and gives an opportunity to clear up any misunderstandings and misperceptions.

- Problems of incompatible working styles or excessive work demands are matters which can be taken, informally, to your supervisor: they will best be able to help you develop solutions to the problem.

- If your dissatisfaction is with someone in authority over you, or about your own status, you may have to discuss the matter with someone higher up in the organisation: this is probably best handled using more formal channels.

- Negotiate

Where interests or styles are genuinely incompatible, or work demands are unmanageable, you may need to work together to explore a range of options that will at least partially satisfy both parties. You may have to make a concession in order to gain a concession: this is called compromise. However, the best approach is to attempt to find a mutually satisfying solution: a win-win.

- Separate

If personality clash is the main source of conflict, you may have to arrange (or request) a way of dealing with the other person as little as possible. It may be within your power to simply walk away from potential conflicts, rather than allow yourself to participate. If the problems persist, you may need to initiate formal conflict resolution proceedings: to have a third party mediate – or to physically separate you in different areas, duties or departments.

5.2.1 Managing conflict in the team

Management responses to the handling of conflict (not all of which are effective).

| Response | Comment |

| Denial/withdrawal | ‘Sweeping it under the carpet’. If the conflict is very trivial, it may indeed blow over without an issue being made of it, but if the causes are not identified, the conflict may grow to unmanageable proportions. |

| Suppression | ‘Smoothing over’, to preserve working relationships despite minor conflicts. |

| Dominance | The application of power or influence to settle the conflict. The disadvantage of this is that it creates all the lingering resentment and hostility of ‘win-lose’ situations. |

| Compromise | Bargaining, negotiating, conciliating. To some extent, this will be inevitable in any organisation made up of different individuals. However, individuals tend to exaggerate their positions to allow for compromise, and compromise itself is seen to weaken the value of the decision, perhaps reducing commitment. |

| Integration/collaboration | Emphasis must be put on the task, individuals must accept the need to modify their views for its sake, and group effort must be seen to be superior to individual effort. |

| Encourage co-operative behaviour | Common goals may be set for all teams/departments. This would encourage co-operation and joint problem-solving. |

QUESTION Conflict resolution

In the light of the above consider how conflict could arise, what form it would take and how it might be resolved in the following situations.

- Two managers who share a secretary have documents to be typed.

- One worker finds out that another worker who does the same job as he does is paid a higher wage.

- A company’s electricians find out that a group of engineers have been receiving training in electrical work.

- Department A stops for lunch at 12:30pm while Department B stops at 1pm. Occasionally the canteen runs out of puddings for Department B workers.

- The Northern Region and Southern Region sales teams are continually trying to better each other’s results, and the capacity of production to cope with the increase in sales is becoming overstretched.

ANSWER

- Both might need work done at the same time. Compromise and co-ordinated planning can help them manage their secretary’s time.

- Differential pay might result in conflict with management – even an accusation of discrimination. There may be good reasons for the difference (eg length of service). To prevent conflict such information should be kept confidential. Where it is public, it should be seen to be not arbitrary.

- The electricians are worried about their jobs, and may take industrial action. Yet if the engineer’s training is unrelated to the electricians’ work, management can allay fears by giving information. The electricians cannot be given a veto over management decisions: a ‘win-lose’ situation is inevitable, but both sides can negotiate.

- The kitchen should plan its meals better – or people from both departments can be asked in advance whether they want puddings.

- Competition between sales regions is healthy, as it increases sales. The conflict lies between sales regions and the production department. In the long term, an increase in production capacity is the only solution. Where this is not possible, proper co-ordination methods should be instituted.

5.3 A win-win approach

One useful model of conflict resolution is the win-win model. This states that there are three basic ways in which a conflict or problem can be worked out.

| Method | Frequency | Explanation |

| Win-lose | This is quite common. | One party gets what they want at the expense of the other party:

for example, Department A gets the new photocopier, while Department B keeps the old one (since there were insufficient resources to buy two new ones). However well justified such a solution is (Department A needed the facilities on the new photocopier more than Department B), there is often lingering resentment on the part of the ‘losing’ party, which may begin to damage work relations. |

| Lose-lose | This sounds like a senseless outcome, but actually compromise comes into this category. It is thus very common. | Neither party gets what they really wanted: for example, since Department A and B cannot both have a new photocopier, it is decided that neither department should have one. However ‘logical’ such a solution is, there is often resentment and dissatisfaction on both sides. (Personal arguments where neither party gives ground and both end up storming off or not talking are also lose-lose: the parties may not have lost the argument, but they lose the relationship …) Even positive compromises only result in halfsatisfied needs. |

| Win-win | This may not be common, but working towards it often brings out the best solution. | Both parties get as close as possible to what they really want. How can this be achieved? |

It is critical to the win-win approach to discover why both parties really want something.

- They want something because they have not considered any other options.

- They can get away with having something.

- They need something in order to avoid an outcome they fear.

Department B may want the new photocopier because they have never found out how to use all the features (which do the same things) on the old photocopier; because they just want to have the same equipment as Department A; or because they fear that if they do not have the new photocopier, their work will be slower and less professionally presented.

To get to the heart of what people really need and want, the important questions in working towards winwin are:

- What do you want this for?

- What do you think will happen if you don’t get it?

In our photocopier example, Department A says it needs the new photocopier to make colour copies (which the old copier does not do), while Department B says it needs the new copier to make clearer copies (because the copies on the old machine are a bit blurred). Now there are options to explore. It may be that the old copier just needs fixing in order for Department B to get what it really wants. Department A will still end up getting the new copier – but Department B has in the process been consulted and had its needs met.

Win-win is not always possible: it is working towards it that counts. The result can be mutual respect and co-operation, enhanced communication, more creative problem-solving and – at best – satisfied needs all round.

QUESTION You win again

Suggest a (i) win-lose, (ii) compromise and (iii) win-win solution in the following scenarios.

- Two of your team members are arguing over who gets the desk by the window: they both want it.

- You and a colleague both need access to the same file at the same time. You both need it to compile reports for your managers, for the following morning. It is now 3pm, and each of you will need it for two hours to do the work.

- Manager A is insisting on buying new computers for her department before the budgetary period ends. Manager B cannot understand why, since the old computers are quite adequate. She will moreover be severely inconvenienced by such a move, since her own systems will have to be upgraded as well in order to remain compatible with department A (the two departments constantly share data files). Manager B protests, and conflict erupts.

ANSWER

- (i) Win-lose: one team member gets the window desk, and the other does not. (Result: broken relationships within the team.)

- Compromise: the team members get the window desk on alternate days or weeks. (Result: half satisfied needs.)

- Win-win: what do they want the window desk for? One may want the view, the other better lighting conditions. This offers options to be explored: how else could the lighting be improved, so that both team members get what they really want? (Result: at least, the positive intention to respect everyone’s wishes equally, with benefits for team communication and creative problem-solving.)

- (i) Win-lose: one of you gets the file and the other doesn’t.

- Compromise: one of you gets the file now, and the other gets it later (although this has an element of win-lose, since the other has to work late or take it home).

- Win-win: you photocopy the file and both take it, or one of you consults your boss and gets an extension of the deadline (since getting the job done in time is the real aim – not just getting the file). These kind of solutions are more likely to emerge if the parties believe they can both get what they want.

- (i) Win-lose: Manager A gets the computers, and Manager B has to upgrade her systems.

- Compromise: Manager A will get some new computers, but keep the same old ones for continued data sharing with Department B. Department B will also need to get some new computers, as a back-up measure.

- Win-win: what does Manager A want the computers for, or to avoid? Quite possibly, she needs to use up her budget allocation for buying equipment before the end of the budgetary period: if not, she fears she will lose that budget allocation. However, that may not be the case, or there may be other equipment that could be more usefully purchased – in which case, there is no losing party.

5.4 The limits of your ability and authority to resolve relationship issues

Resolving difficulties in working relationships may be:

- Beyond your authority

Difficulties arising from work demands, work methods and status, for example, may require the intervention of someone who has the authority to change work schedules, reorganise work – and discipline unco-operative subordinates and colleagues (or even superiors) if necessary.

- Beyond your ability

You may have done your best to resolve personality clashes or to solve other problems, but the situation or relationship may just not be improving. It may require a wider perspective, more developed interpersonal skills, or special expertise in conflict resolution.

In these cases, you may need to mobilise organisational procedures for formal grievance handling.

5.5 Formal grievance procedures

A grievance occurs when an individual thinks that they are being wrongly treated by their colleagues or supervisors; that is, when working relationships break down.

The individual may consider that they are being picked on, being given an unfair workload, unfairly appraised in the annual report or unfairly blocked for promotion, or discriminated against.

When an individual has a grievance they should be able to pursue it and ask to have the problem resolved.

If one to one discussion has not worked, a more formal approach will be needed. A typical grievance procedure provides for the following steps.

| Step 1 | The grievance should be carefully explained to the aggrieved individual’s immediate boss (unless they are the subject of the complaint, in which case it will be the next level up). Employees have the right to be accompanied by a colleague or representative to such an interview, if they feel they need support or a witness. |

| Step 2 | If the immediate boss or other person cannot resolve the matter, or an employee is otherwise dissatisfied with the first interview, the case should be referred to the next level of management (and if necessary, in some cases, to an even higher authority). |

| Step 3 | Cases referred to a higher manager should also be reported to the personnel department, for the assistance/advice of a personnel manager in resolving the problem. |

All complaints should be thoroughly investigated, so if you do find that you have to go through a formal grievance procedure it is important that you are honest and fair. Records should be kept of all interviews and actions taken – and these should be confidential.

QUESTION Grievance procedures

Check what the grievance procedures are in your organisation! If there is nothing set out in your job description or procedures manual, ask the personnel department.

ANSWER

Your own observations.

| 6 | Communication in the workplace |

6.1 Communication in the organisation

| Communication is a two-way process involving the transmission or exchange of information and the provision of feedback. It is necessary to direct and co-ordinate activities. |

Communication is required for planning, co-ordination and control.

- Management decision-making requires data. Managers are at the hub of a communications system.

- Interdepartmental co-ordination depends on information flows. All the interdependent systems for purchasing, production, marketing and administration can be synchronised to perform the right actions at the right times to co-operate in accomplishing the organisation’s aims.

- Individual motivation and effectiveness depends on communication, so that people know what they have to do and why.

Communication in the organisation may take the following forms.

- Giving instructions

- Giving or receiving information

- Exchanging ideas

- Announcing plans or strategies

- Comparing actual results against a plan

- Rules or procedures

- Communication about the organisation structure and job descriptions

| Communication in an organisation flows downwards, upwards, sideways and diagonally. |

6.2 Direction of communication

Communication links different parts of the organisation.

- Vertical communication flows up and down the scalar chain from superior to subordinate and back.

- Horizontal or lateral communication flows between people of the same rank, in the same section or department, or in different sections or departments. Horizontal communication between peer groups is usually easier and more direct then vertical communication, being less inhibited by considerations of rank. It may be part of a formal work relationship, to co-ordinate the work of several people, and perhaps departments, who have to co-operate to carry out a certain operation. Alternatively, informal communication may furnish emotional and social support to an individual.

- Interdepartmental communication by people of different ranks may be described as diagonal communication. Departments in the technostructure which serve the organisation in general, such as Human Resources or Information Systems, have no clear line authority linking them to managers in other departments who need their involvement.

6.3 Communication patterns (or networks)

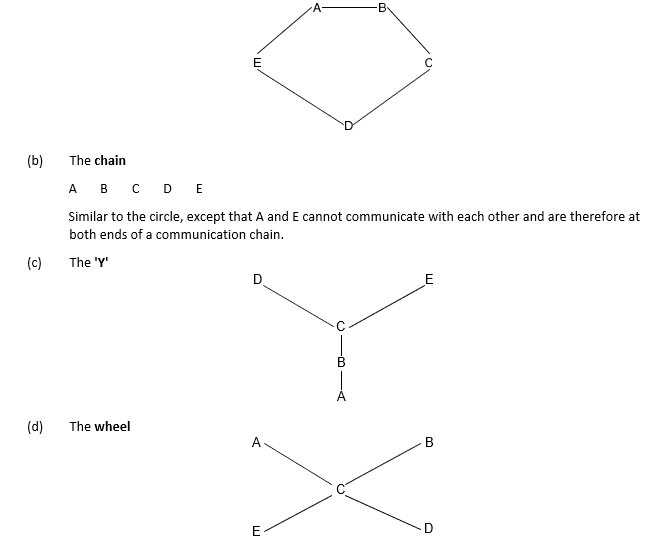

A communication pattern channels communication between people. One of the purposes of a formal organisation structure is the design of a communications pattern for the organisation.

Leavitt (1951), in a series of experiments, examined the effectiveness of four communication networks for written communication between members of a small group.

- The circle. Each member of the group could communicate with only two others in the group, as shown.

In both the ‘Y’ and the ‘wheel’ patterns, C occupies a more central position in the network.

| Wheel | Y | Chain | Circle | |

| Speed of problem-solving | Fastest | 2nd fastest | 3rd fastest | Slowest |

| Leader | C | C | C (less so than wheel and Y) | None emerged |

| Job satisfaction | Lowest | 3rd highest | 2nd highest | Highest(?) |

In Leavitt’s experiment, each member of a group of five people had to solve a problem and each had an essential piece of information. Only written communication, channelled according to one of the four patterns described above, was allowed. The findings of the experiment are tabulated below. A direct trade off between speed and job satisfaction is evident.

6.4 Internal information

| Data and information come from sources both inside and outside an organisation. An organisation’s information systems should be designed so as to obtain – or capture – all the relevant data and information required. |

Capturing data and information from inside the organisation involves designing a system for collecting or measuring data and information which sets out procedures for:

- What data and information is collected

- How frequently

- By whom

- By what methods

- How data and information is processed, filed and communicated

6.4.1 The accounting records

The accounting ledgers provide an excellent source of information regarding what has happened in the past. This information may be used as a basis for predicting future events eg budgeting.

Accounting records can provide more than purely financial information. For example, an inventory control system includes purchase orders, goods-received notes and goods-returned notes that can be analysed to provide information regarding the speed of delivery or the quality of supplies. Receivables ledgers can provide sales information for the marketing function.

6.4.2 Other internal sources

Much information that is not strictly part of the accounting records nevertheless is closely tied in to the accounting system.

- Information about personnel will be linked to the payroll Additional information may be obtained from this source if, say, a project is being costed and it is necessary to ascertain the availability and rate of pay of different levels of staff, or the need for and cost of recruiting staff from outside the organisation.

- Much information will be produced by a production department about machine capacity, fuel consumption, movement of people, materials, and work in progress, set up times, maintenance requirements, and so on. A large part of the traditional work of cost accounting involves ascribing costs to the physical information produced by this source.

- Many service businesses, notably accountants and solicitors, need to keep detailed records of the time spent on various activities, both to justify fees to clients and to assess the efficiency and profitability of operations.

Staff themselves are one of the primary sources of internal information. Information may be obtained either informally in the course of day-to-day business or through meetings, interviews or questionnaires.

6.5 External information

Formal collection of data from outside sources includes the following.

- A company’s tax specialists will be expected to gather information about changes in tax law and how this will affect the company.

- Obtaining information about any new legislation on health and safety at work, or employment regulations, must be the responsibility of a particular person – for example the company’s legal expert or company secretary – who must then pass on the information to other managers affected by it.

- Research and development (R&D) work often relies on information about other R&D work being done by another company or by government institutions. An R&D official might be made responsible for finding out about R&D work in the company.

- Marketing managers need to know about the opinions and buying attitudes of potential customers. To obtain this information, they might carry out market research exercises.

Informal gathering of information from the environment occurs naturally, consciously or unconsciously, as people learn what is going on in the world around them – perhaps from newspapers, television reports, meetings with business associates or the trade press.

Organisations hold external information, such as invoices, letters and advertisements, received from customers and suppliers. But there are many occasions when an active search outside the organisation is necessary.

The phrase environmental scanning is often used to describe the process of gathering external information, which is available from a wide range of sources.

- The Government

- Advice or information bureaux eg Reuters

- Consultants

- Newspaper and magazine publishers

- There may be specific reference works which are used in a particular line of work

- Libraries and information services

- Increasingly businesses can use each other’s systems as sources of information, for instance via extranets or electronic data interchange (EDI)

- Electronic sources of information are becoming increasingly important

- For some time there have been ‘viewdata’ services, such as Prestel, offering a very large bank of information gathered from organisations including the Office for National Statistics, newspapers and the British Library. Topic offers information on the stock market. Companies like Reuters operate primarily in the field of provision of information – often in electronic form.

(ii) The internet is a vast source of information.

6.6 Efficient data collection

To produce meaningful information it is first necessary to capture the underlying data. The method of data collection chosen will depend on the nature of the organisation, cost and efficiency. Some common data collection methods are listed below.

- Document reading methods

6.7 Why do organisations need information?Magnetic ink character recognition (MICR)

- Optical mark reading (OMR)

- Scanners and optical character recognition (OCR)

- Bar coding and Electronic Point of Sale (EPOS)

- Electronic Funds Transfer at the Point of Sale (EFTPOS)

- Magnetic stripe cards

- Smart cards

- Touch screens

- Voice recognition

- Data is the raw material for data processing. Data consists of numbers, letters and symbols and relates to facts, events and transactions.

- Information is data that has been processed in such a way as to be meaningful to the person who receives it.

| Organisations require information for a range of purposes.

• Planning Decision-making • Controlling |

6.7.1 Planning

Once any decision has been made, it is necessary to plan how to implement the steps necessary to make it effective. Planning requires a knowledge of, among other things, available resources, possible timescales for implementation and the likely outcome under alternative scenarios.

6.7.2 Controlling

Once a plan is implemented, its actual performance must be controlled. Information is required to assess whether it is proceeding as planned or whether there is some unexpected deviation from the plan. It may consequently be necessary to take some form of corrective action.

6.7.3 Decision-making

Information is also required to make informed decisions. This completes the full circle of organisational activity.

6.8 The qualities of good information

| Good information has a number of specific qualities: the mnemonic ACCURATE is a useful way of remembering them. |

| Quality | Example |

| Accurate | Figures should add up, the degree of rounding should be appropriate, there should be no typos, items should be allocated to the correct category and assumptions should be stated for uncertain information (no spurious accuracy). |

| Complete | Information should include everything that it needs to include, for example external data if relevant, or comparative information. |

| Costbeneficial | It should not cost more to obtain the information than the benefit derived from having it. Providers of information should be given efficient means of collecting and analysing it. Presentation should be such that users do not waste time working out what it means. |

| User targeted | The needs of the user should be borne in mind, for instance senior managers may require summaries, junior ones may require detail. |

| Relevant | Information that is not needed for a decision should be omitted, no matter how ‘interesting’ it may be. |

| Authoritative | The source of the information should be a reliable one (not, for instance, ‘Joe Bloggs Predictions Page’ on the internet unless Joe Bloggs is known to be a reliable source for that type of information. |

| Timely | The information should be available when it is needed. |

| Easy to use | Information should be clearly presented, not excessively long, and sent using the right medium and communication channel (email, telephone, hard-copy report, etc). |

The qualities of good information are outlined below – in mnemonic form. If you think you have seen this before, note that the second A here stands for ‘Authoritative’, an increasingly important concern given the huge proliferation of information sources available today.

6.9 Information in the organisation

A modern organisation requires a wide range of systems to hold, process and analyse information. We will now examine the various information systems used to serve organisational information requirements.

Organisations require different types of information system to provide different levels of information in a range of functional areas.

| System level | System purpose |

| Strategic | To help senior managers with long-term planning. Their main function is to ensure changes in the external environment are matched by the organisation’s capabilities. |

| Management/

tactical |

To help middle managers monitor and control. These systems check if things are working well or not. Some management-level systems support non-routine decision-making, such as ‘what if?’ analyses. |

| Operational | To help operational managers track the organisation’s day-to-day operational activities. These systems enable routine queries to be answered, and transactions to be processed and tracked. |

6.9.1 Example

Finance subsystem

- The operational level would deal with cash receipts and payments, bank reconciliations and so forth.

- The tactical level would deal with cash flow forecasts and working capital management.

- Strategic level financial issues are likely to be integrated with the organisation’s commercial strategy, but may relate to the most appropriate source of finance (eg long-term debt, or equity).

The type of information at each level can be seen in the table below.

| Inputs | Process | Outputs | |

| Strategic | Plans, competitor information, overall market information | Summarise

Investigate Compare Forecast |

Key ratios, ad hoc market analysis, strategic plans |

| Management/tactical | Historical and budget data | Compare

Classify Summarise |

Variance analyses

Exception reports |

| Operational | Customer orders, programmed inventory control levels, cash receipts/payments | Update files

Output reports |

Updated file listings, invoices |

| 7 | Formal communication processes |

7.1 The communication process

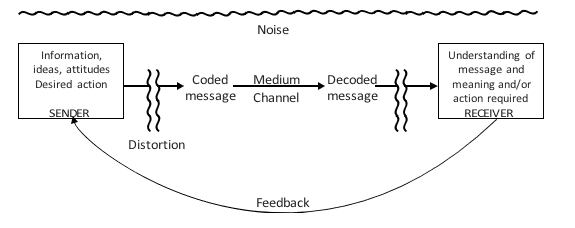

|

| Process | Comment |

| Encoding of a message | The code or ‘language’ of a message may be verbal (spoken or written) or it may be non-verbal, in pictures, diagrams, numbers or body language. |

| Medium for the message | There are a number of channels for communication, such as a conversation, a letter, a noticeboard or via computer. The choice of medium used in communication depends on a number of factors, such as urgency, permanency, complexity, sensitivity and cost. |

| Feedback | The sender of a message needs feedback on the receiver’s reaction. This is partly to test the receiver’s understanding of it and partly to gauge the receiver’s reaction. |

| Distortion | The meaning of a message can be lost at the coding and decoding stages. Usually the problem is one of language and the medium used; it is very easy to give the wrong impression in a brief email message. |

| Noise | Distractions and interference in the environment in which communication is taking place may be physical noise (passing traffic), technical noise (a bad telephone line), social noise (differences in the personalities of the parties) or psychological noise (anger, frustration, tiredness). |

7.2 Desirable qualities of a communication system in an organisation

Clarity. The coder of a message must bear in mind the potential recipient. Jargon can be used – and will even be most appropriate – where the recipient shares the same expertise. It should be avoided for those who do not.

Recipient. The recipient should be clearly identified, and the right medium should be chosen, to minimise distortion and noise.

Medium. The channel or medium should be chosen to ensure it reaches the target audience. Messages of general application (eg health and safety signs) should be displayed prominently.

Timing. Information has to be timely to be useful.

7.3 Effective communication

|

What does ‘good communication’ look like? It is perhaps easiest to identify poor or ineffective communication, where information is not given; is given too late to be used; is too much to take in; is inaccurate or incomplete; is hard to understand. Effective communication is:

- Directed to appropriate people. This may be defined by the reporting structure of the organisation, but it may also be a matter of discretion, trust, and so on.

- Relevant to their needs. Information should be non-excessive in volume (causing overload); focused on relevant topics; communicated in a format, style and language that they can understand.

- Accurate and complete (within the recipient’s needs). Information should be ‘accurate’ in the sense of ‘factually correct’, but need not be minutely detailed: in business contexts, summaries and approximations are often used.

- Timely. Information must be made available within the time period when it will be relevant (as input to a decision, say).

- Flexible. Information should be suited in style and structure to the needs of the parties and situation. Assertive, persuasive, supportive and informative communication styles have different applications.

- Effective in conveying meaning. Style, format, language and media all contribute to the other person’s understanding or lack of understanding. If the other person doesn’t understand the message, or misinterprets it, communication has not been effective.

- Cost effective. In business organisations, all the above must be achieved, as far as possible, at reasonable cost.

| 8 | Informal communication channels | |||

|

||||

The formal pattern of communication in an organisation is always supplemented by an informal one, which is sometimes referred to as the grapevine. People like to gossip about rumours and events.

8.1 The grapevine

The grapevine has a number of characteristics.

- The grapevine acts quickly.

- The working of the grapevine is selective: information is not divulged randomly.

- The grapevine usually operates at the place of work and not outside it.

- Oddly, the grapevine is most active when the formal communication network is active: the grapevine does not fill a gap created by an ineffective formal communication system.

- Higher-level executives were better communicators and better informed than their subordinates.

- More technostructure executives were in the know about events than line managers (because the staff executives are more mobile and get involved with more different functions in their work).

8.2 The importance of informal communications

Managers, rather than staff, might rely on the grapevine, as opposed to formal communication channels, because of the qualities informal communication possesses.

- It is more current than the formal system.

- It is relevant to the informal organisation (where many decisions are actually determined).

- It relates to internal politics, which may not be reflected in formal communications anyway.

- It can bypass excessively secretive management.

8.3 Interpersonal skills

Interpersonal skills are needed in order to understand and manage roles, relationships, attitudes and perceptions. They enable us to communicate effectively and to achieve our aims when dealing with other people.

Interpersonal skills

- The ability to interpret body language and to use it to reinforce messages

- The ability to listen attentively and actively

- The ability to put others at their ease, to persuade and to smooth over difficult situations

- The ability to identify when false or dishonest arguments are being used, and to construct logical ones

- The ability to recognise how much information, and of what kind, another person will need and be able to take in

- The ability to use communication media effectively: to speak well, write legibly, use appropriate vocabulary and use visual aids where required

- The ability to sum up or conclude an argument clearly and persuasively (h) The ability to communicate and show enthusiasm, ie leadership or inspiration The above list is by no means exhaustive.

Here are some more important things to consider in interpersonal relations.

| Factor | Comment |

| Goal | What does the other person want from the process? What do you want from the process? What will both parties need and be trying to do to achieve their aims? Can both parties emerge satisfied? |

| Perceptions | What, if any, are likely to be the factors causing distortion of the way both parties see the issues and each other? (Attitudes, personal feelings, expectations?) |

| Roles | What roles are the parties playing? (Superior/subordinate, customer/server, complainer/soother?) What expectations does this create of the way they will behave? |

| Resistances | What may the other person be afraid of? What may they be trying to protect? (Their ego/self-image, attitudes?) Sensitivity will be needed in this area. |

| Attitudes | What sources of difference, conflict or lack of understanding might there be, arising from attitudes and other factors which shape them (sex, race, specialism, hierarchy)? |

| Relationships | What are the relative positions of the parties and the nature of the relationship between them? (Superior/subordinate? Formal/informal? Work/non-work)? What style is appropriate to it? |

| Environment | What factors in the immediate and situational environment might affect the issues and the people? (Eg competitive environment; customer care; pressures of disciplinary situation; nervousness; physical surroundings formality/informality) |

8.3.1 Listening

Listening in the communications model is about decoding and receiving information. Effective listening has three consequences.

- It encourages the sender to listen effectively in return to what you have to say.

- It reduces the effect of noise.

- It helps resolve problems by encouraging understanding from someone else’s viewpoint.

Advice for good listening

- Be prepared to listen. Put yourself in the right frame of mind and be prepared to grasp the main concepts.

- Be interested. Make an effort to analyse the message for its relevance.

- Keep an open mind. Your own beliefs and prejudices can get in the way of what the other person is actually saying.

- Keep an ear open for the main ideas. An awareness of how people generally structure their speech can help the process of understanding. Be able to distinguish between the thrust of the argument and the supporting evidence.

- Listen critically. This means trying to assess what the person is saying by identifying any assumptions, omissions and biases.

- Avoid distraction. People have a natural attention curve, high at the beginning and end of an oral message, but sloping off in the middle.

- Take notes. However, note taking can be distracting.

8.3.2 Non-verbal communication: body language

The hidden messages in face-to-face communication can be a common cause for communication breakdown, as they cause decoding problems. Observe others in meetings, presentations, interviews or just talking in the bar. Notice the signs of boredom or disagreement, support and interest. Picking up these signals will help you improve your own communication skills.

While watching others, also become more aware of yourself. Be aware of the signals you are sending and transmit only those you intend to.

Non-verbal communication can be controlled and used for several purposes.

- It can provide appropriate feedback to the sender of a message (a yawn, applause, clenched fists, fidgeting).

- It can create a desired impression (smart dress, a smile, punctuality, a firm handshake).

- It can establish a desired atmosphere or conditions (a friendly smile, informal dress, attentive posture, a respectful distance).

- It can reinforce spoken messages with appropriate indications of how interest and feelings are engaged (an emphatic gesture, sparkling eyes, a disapproving frown).

If we can learn to recognise non-verbal messages, our ability to listen is improved.

- When we are speaking, non-verbal feedback helps us to modify our message.

- We may recognise people’s real feelings when their words are constrained by formal courtesies (an excited look, a nervous tic, close affectionate proximity).

- We can recognise existing or potential personal problems (the angry silence, the indifferent shrug, absenteeism or lateness at work, refusal to look someone in the eye).

Non-verbal cues

- Facial expression

- Movement and stillness

- Gesture

- Silence and sounds

- Posture and orientation

- Appearance and grooming

- Proximity and contact

- Response to norms and expectations

8.4 Observation

While not really a form of communication, observation as a management skill is linked to topics in communication such as interviewing, so it is convenient to deal with it here.

Observation is an important data-gathering technique. It can be used to measure the effectiveness of procedures, or, indeed, to establish just what procedures and processes are in use. It is perhaps most useful in establishing the nature of less formal aspects of the organisation, such as how the informal organisation works; how individuals perform their tasks; who interacts with whom; and how specified procedures are informally modified.

| 9 | Barriers to communication | |||

|

||||

- General faults in the communication process

Distortion or omission of information by the sender

Misunderstanding due to lack of clarity or technical jargon

Non-verbal signs (gesture, posture, facial expression) contradicting the verbal message, so that its meaning is in doubt

‘Overload’ – a person being given too much information to digest in the time available

People hearing only what they want to hear in a message

Differences in social, racial or educational background, compounded by age and personality differences, creating barriers to understanding and co-operation

(Mnemonic using words in bold above: Distorted Messages Never Overcome Personal Differences.)

- Communication difficulties at work

Status (of the sender and receiver of information)

- A senior manager’s words are listened to closely and a colleague’s perhaps discounted.

- A subordinate might mistrust their superior believing that they might look for hidden meanings in a message.

Jargon. People from different job or specialist backgrounds (eg accountants, personnel managers, IT experts) can have difficulty in talking on a non-specialist’s wavelength.

Suspicion. People discount information from those not recognised as having expert power.

Priorities. People or departments have different priorities or perspectives so that one person places more or less emphasis on a situation than another.