MISSION STATEMENTS AND VISION

Vision is oriented towards the future, to give a sense of direction to the organisation. Mission describes an organisation’s basic purpose, what it is trying to accomplish.

Underlying the behaviour and management processes of most organisations are one or two guiding ideas, which influence the organisation’s activities. Management writers typically analyse these into two categories: vision and mission.

Mission: What is the business for?

Vision: Where is the business going?

Case Study

Beyond petroleum

Vision

In the early 1990s, BP articulated its ‘vision’ as follows:

‘With our bold, innovative strategic agenda, BP will be the world’s most successful oil company in the 1990s and beyond.’

In the early 2000s, BP effectively rebranded itself, with an advertising campaign with the strapline ‘beyond petroleum’. Although petrol is the world’s principal source of global warming, BP is trying to promote an ‘environmentally conscious’ message, by repositioning itself as an energy company and investing more in alternative or renewable sources of energy such as solar power.

Arguably, the ‘vision’ has changed. From the stated desire to be the world’s most successful oil company, BP has moved to a state ‘beyond’ petroleum. The point is that as a business progresses, its vision will need to be “updated”.

But what about mission? Mission describes the purpose of the company, in other words why it exists at all. Many organisations interpret their mission in terms of stakeholders, typically the owners or shareholders and customers.

BP once described itself as follows:

‘BP is a family of businesses principally in oil and gas exploration and production, refining and marketing, chemicals and nutrition. In everything we do we are committed to creating wealth, always with integrity, to reward the stakeholders in BP – our shareholders, our employees, our customers and suppliers and the community.’

Case Study

The Times Online reported the result of research by Bain & Company (Bain & Company’s Management Tools 2005 survey) which found that 72% of companies have a vision or mission statement. However the survey also reported that 88% of companies had them back in 1993.

The survey concluded that ‘They are a fashion staple which is in decline’.

Vision

A vision for the future has three aspects.

- What the business is now

- What it could be in an ideal world

- What the ideal world would be like

A vision gives a general sense of direction to the company. A vision, it is hoped, enables flexibility to exist in the context of a guiding idea.

Mission

Mission ‘describes the organisation’s basic function in society, in terms of the products and

services it produces for its clients’. (Mintzberg)

Case Study

The Co-op

The Co-operative movement (The Co-operative Group is the UKs larget mutual business – owned by its members most of whom are customers) in the UK is a good example of the role of mission. Its mission is not simply profit. Being owned by suppliers/customers rather than external shareholders, it has always, since its foundation, had a wider social concern.

“The Co-op” has been criticised by some analysts on the grounds that it is insufficiently profitable, certainly in comparison with supermarket chains such as Tesco in the UK or Simba and Nakumatt in Rwanda. The Co-op has explicit social objectives, however. In some cases it will retain stores which, although too small to be as profitable as a large supermarket, provide an important social function in the communities which host them.

Of course, the Co-op’s performance as a retailer can be improved, but judging it on the conventional basis of profitability ignores its social objectives.

An expanded definition of mission includes four elements.

| Elements of mission | Detail |

| Purpose | Why does the company exist?

• To create wealth for shareholders? • To satisfy the needs of all stakeholders (including employees, society at large, for example)? |

| Strategy | Mission provides the commercial logic for the company, and so defines the following.

• Nature of its business • Products/services it offers; competitive position • The competences and competitive advantages by which it hopes to prosper, and its way of competing |

| Policies and standards of behaviour | The mission needs to be converted into everyday performance. For example, a firm whose mission covers excellent customer service must deal with simple matters such as politeness to customers, speed at which phone calls are answered and so forth. |

| Values and culture | Values are the basic, perhaps unstated, beliefs of the people who work in the organisation |

Mission statements

A mission statement should be brief, flexible and distinctive, and is likely to place an emphasis on serving the customer.

Although many organisations do not have a clearly defined mission, they are becoming increasingly common, especially in larger organisations, and are usually set out in the form of a mission statement. This written declaration of an organisation’s central mission is a useful concept that can:

- Provide a ready reference point against which to make decisions

- Help guard against there being different (and possibly misleading) interpretations of the organisation’s stated purpose

- Help to present a clear image of the organisation for the benefit of customers and the general public

Most mission statements will address some of the following aspects.

- The identity of the persons for whom the organisation exists (such as shareholders, customers and employees)

- The nature of the firm’s business (such as the products it makes or the services it provides, and the markets it produces for)

- Ways of competing (such as reliance on quality, innovation, technology and low prices; commitment to customer care; policy on acquisition versus organic growth; and geographical spread of its operations)

- Principles of business (such as commitment to suppliers and staff; social policy, for example, on non-discrimination or environmental issues)

- Commitment to customers

A number of questions need to be considered when a mission statement is being formulated.

- Who is to be served and satisfied?

- What need is to be satisfied?

- How will this be achieved?

Case Study

The Financial Times reported the result of research by the Digital Equipment Corporation into a sample of 429 company executives.

- 80% of the sample have a formal mission statement.

- 80% believed mission contributes to profitability.

- 75% believe they have a responsibility to implement the mission statement.

Mission statements might be reproduced in a number of places (at the front of an organisation’s annual report, on publicity material, in the chairman’s office, in communal work areas and so on) as they are used to communicate with those inside and outside the organisation.

There is no standard format, but they should possess certain characteristics.

- Brevity – easy to understand and remember

- Flexibility – to accommodate change

- Distinctiveness – to make the firm stand out

- Open-ended – not stated in quantifiable terms

They tend to avoid commercial terms (such as profit) and do not refer to time frames (some being carved in stone or etched on a plaque!).

A mission does not have to be internally oriented. Some of the most effective focus outwards – on customers and/or competitors. Most mission statements tend to place an emphasis on serving the customer.

Case Study

Private sector organisations (such as Bank of Kigali Ltd, Bralirwa Ltd or Agro-Live) traditionally seek to make a profit, but increasingly companies try to project other images too, such as being environmentally friendly, being a good employer, or being a provider of friendly service. Here’s one such example.

The Bank of Kigali: Vision: Bank of Kigali aspires to be the leading provider of most innovative financial solutions in the region.

And the mission: Our mission is to be the leader in creating value for our stakeholders by providing the best financial services to businesses and individual customers, through motivated and professional staff.

Public sector organisations (such as district councils, universities, colleges and hospitals) provide services and increasingly seek to project quality, value for money, green issues, concern for staff (equal opportunities) and so on as missions. This is illustrated by the following examples.

For instance: ‘The University of Bradford (in UK) makes knowledge work through accessible programmes of teaching, learning and research with particular emphasis on applied and multi-disciplinary areas of study. It aims to support students in developing the knowledge, understanding and skills that will enable them to fulfil their intellectual and personal potential, and thereby make a mature and critical contribution to society. It aims to attract and retain high quality academic staff, actively engaged in teaching and research.’

(University of Bradford)

Voluntary and community sector organisations cover a wide range of organisations including charities, trades unions, pressure groups and religious organisations. They usually exist either to serve a particular need or for the benefit of their membership. Such organisations do need to raise funds but they will rarely be dedicated to the pursuit of profit. Their mission statements are likely to reflect the particular interests they serve (and perhaps the values of their organisation). Here are some examples.

‘We work to preserve the diversity and abundance of life on earth and the health of ecological systems by:

- Protecting natural areas and wild populations of plants and animals

- Promoting sustainable approaches to the UK of renewable natural resources

- Promoting more efficient use of resources and energy and the maximum

reduction of pollution’

(The World Wide Fund for Nature)

- b) The following statements were taken from annual reports of the organisations concerned. Are they mission statements? If so, are they any good?

- Before its succession of mergers, Glaxo, now GlaxoSmithKline, described itself as ‘an integrated research-based group of companies whose corporate purpose is to create, discover, develop, manufacture and market throughout the world, safe, effective medicines of the highest quality which will bring benefit to patients through improved longevity and quality of life, and to society through economic value.’

- The British Film Institute claimed ‘The BFI is the UK national agency with responsibility for encouraging and conserving the arts of film and television. Our aim is to ensure that the many audiences in the UK are offered access to the widest possible choice of cinema and television, so that their enjoyment is enhanced through a deeper understanding of the history and potential of these vital and popular art forms.’

Mission and planning

Although the mission statement might be seen as a set of abstract principles, it can play an important role in the planning process.

- Inspires planning. Plans should develop activities and programmes consistent with the organisation’s mission.

- Screening. Mission also acts as a yardstick by which plans are judged.

- Mission also affects the implementation of a planned strategy, in the culture and business practices of the firm.

Factors to incorporate in a mission statement

- The business areas in which the organisation will operate

- The organisation’s reason for existence

- The stakeholder groups served by the organisation

GOALS AND OBJECTIVES: AN INTRODUCTION

Goals and objectives are set out to give flesh to the mission in any particular period.

Definitions

There is much confusion over the terms ‘goals’ and ‘objectives’. Some writers use the terms interchangeably while others refer to them as two different concepts, unfortunately with no consistency as to which term refers to which concept. Here we will use the following definitions/distinctions.

- (Shorter-term) objectives are the means by which (longer-term) goals can ultimately be achieved.

- Goals are based on an individual’s value system whereas objectives are based on practical needs.

- Goals are therefore more subjective than objectives.

In particular, operational goals can be expressed as quantified (SMART) objectives: Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Results-oriented, Time-bounded

- Mission: deliver a quality service

- Goal: enhance manufacturing quality

- Objectives: over the next twelve months, reduce the number of defects to 1 part per million

Non-operational goals or aims cannot be expressed as objectives.

- A university’s goal might be to ‘seek truth’. This cannot really be expressed as a quantified objective. To ‘increase truth by 5% this year’ does not make a great deal of sense.

- Customer satisfaction is a goal, but satisfying customers and ensuring that they remain satisfied is a continuous process that does not stop when one target has been reached.

In practice, most organisations set themselves quantified objectives in order to enact the corporate mission.

Features of goals and objectives in organisations

Goal congruence. Goals should be consistent with each other.

-

- Across all departments. There should be horizontal In other words, the goals set for different parts of the organisation should be consistent with each other.

- At all levels. Objectives should be consistent vertically, in other words at all levels in the organisation.

- Over time. Objectives should be consistent with each other over time.

An objective should identify the beneficiaries as well as the nature and size of the benefit.

Types of goal, how they are developed and set

| Goal | Comment |

| Ideological goals | These goals focus on the organisation’s mission. They are shared sets of beliefs and values. |

| Formal goals | These are imposed by a dominant individual or group such as shareholders. People work to attain these goals as a route to their personal goals. |

| Shared personal goals | Individuals reach a consensus about what they want out of an organisation (e.g. a group of academics who decide they want to pursue research). |

| System goals | Derive from the organisation’s existence as an organisation, independent of mission. |

Organisations set goals in a number of different ways.

Goals can be set in many different ways: top down; bottom up; imposed; consensus; precedent.

| Method | Comment |

| Top-down | Goals and objectives are structured from ‘top to bottom’, a cascading process down the hierarchy, with goals becoming more specific the ‘lower’ down the hierarchy. |

| Bottom-up | People in individual departments set their own goals, which eventually shape the overall goals of the organisation. |

| By precedent | Some goals are set simply because they have been set before (e.g. last year’s sales targets plus 5%) |

| By ‘diktat’ | A few key individuals dictate what the goals should be. |

| By consensus | Goals and objectives are achieved by a process of discussion amongst managers – reputedly, Japanese companies employ this approach. |

The setting of objectives is very much a political process: objectives are formulated following bargaining by the various interested parties.

- Shareholders want profits leading to dividends and capital growth.

- Employees want salaries and good working conditions.

- Managers want power.

- Customers demand quality products and services.

These conflicting requirements make it difficult to maximise the objectives of any one particular group. The objectives have to change over time, too, to reflect the changing membership of the groups.

CORPORATE OBJECTIVES

Corporate objectives concern the firm as a whole. Unit objectives are specific to individual units of an organisation.

Corporate objectives are set as part of the corporate planning process. Basically, the corporate planning process is concerned with the selection of strategies which will achieve the corporate objectives of the organisation.

Corporate objectives versus unit objectives

Corporate objectives should relate to the key factors for business success.

- Profitability

- Market share

- Growth

- Cash flow

- Return on capital employed

- Risk

- Customer satisfaction

- Quality

- Industrial relations

- Added value

- Earnings per share

Similar objectives can be developed for each strategic business unit (SBU). (An SBU is a part of the company that for all intents and purposes has its own distinct products, markets and assets.)

Unit objectives, on the other hand, are specific to individual units of an organisation.

| Types | Examples | |

| Commercial | • | Increase the number of customers by x% (an objective of a sales department) |

| • | Reduce the number of rejects by 50% (an objective of a production department) | |

| • | Produce monthly reports more quickly, within 5 working days of the end of each month (an objective of the management accounting department) | |

| Public sector | • | Introduce x% more places at nursery schools (an objective of a local education department) |

| • | Respond more quickly to calls (an objective of a local police station, fire department or hospital ambulance service) | |

| General | • | Resources (e.g. cheaper raw materials, lower borrowing costs, ‘topquality college graduates’) |

| • | Market (e.g. market share, market standing) | |

| • | Employee development (e.g. training, promotion, safety) | |

| • | Innovation in products or processes | |

| • | Productivity (the amount of output from resource inputs) | |

| • | Technology |

Primary and secondary objectives

An organisation has many objectives: even a mission may have multiple parts. It has been argued that there is a limit to the number of objectives that a manager can pursue effectively. Too many and the manager cannot give adequate attention to each and/or the focus may inadvertently be placed on minor ones. Some objectives are more important than others. It has therefore been suggested that there should be one primary corporate objective (restricted by certain constraints on corporate activity) and other secondary objectives. These are strategic objectives which should combine to ensure the achievement of the primary corporate objective.

- For example, if a company sets itself a primary objective of growth in profits, it will then have to develop strategies by which this primary objective can be achieved.

- Secondary objectives might then be concerned with sales growth, continual technological innovation, customer service, product quality, efficient resource management (e.g. labour productivity) or reducing the company’s reliance on debt capital.

SUBSIDIARY OR SECNDARY OBJECTIVES

Primary corporate objectives are supported by secondary objectives, for example for product development or market share. In practice there may be a trade-off between different objectives.

Whatever primary objective(s)is (are) set, subsidiary objectives will then be developed beneath them.

Types of subsidiary objective

Financial

We will be considering these in the next chapter.

Technological

- A commitment to product design and production methods using current and new technology

- A commitment to improve current products through research and development work

- A commitment to a particular level of quality

Product market

| Objectives for products and markets | Comment |

| Market leadership | Whether the organisation wants to be the market leader, or number two in the market etc. |

| Coverage | Whether the product range needs to be expanded |

| Positioning | Whether there should be an objective to shift position in the market – e.g. from producing low-cost for the mass market to higher-cost specialist products |

| Expansion | Whether there should be a broad objective of ‘modernising’ the product range or extending the organisation’s markets |

Product market objectives are key, as the organisation satisfies its shareholders by operating in product market areas. Most major product market objectives are set at corporate level.

Others

- Objectives for the organisation structure are particularly important for growing organisations.

- Productivity objectives. When an organisation is keenly aware of a poor profit record, cost reduction will be a primary consideration. Productivity objectives are often quantified as targets to reduce unit costs and increase output per employee by a certain percentage each year.

- Expansion or consolidation objectives are concerned with the question of whether there is a need to expand, or whether there is a need to consolidate for a while.

Ranking objectives and trade-offs

Where there are multiple objectives a problem of ranking can arise.

- There is never enough time or resources to achieve all of the desired objectives.

- There are degrees of accomplishment. For example, if there is an objective to achieve a 10% annual growth in earnings per share, an achievement of 9% could be described as a near-success. When it comes to ranking objectives, a target ROI of, say, 25% might be given greater priority than an EPS growth of 10%.

When there are several key objectives, some might be achieved only at the expense of others. For example, attempts to achieve a good cash flow or good product quality, or to improve market share, might call for some sacrifice of short-term profits.

For example, there might be a choice between the following two options.

Option A 15% sales growth, 10% profit growth, a RWF10 million negative cash flow and reduced product quality and customer satisfaction

Option B 8% sales growth, 5% profit growth, a RWF5 million surplus cash flow, and maintenance of high product quality/customer satisfaction

If the firm chose option B in preference to option A, it would be trading off sales growth and profit growth for better cash flow, product quality and customer satisfaction. It may feel that the long-term effect of reduced quality would negate the benefits under Option A.

One of the tasks of strategic management is to ensure goal congruence. Some objectives may not be in line with each other, and different stakeholders have different sets of priorities.

Departmental plans and objectives

Implementation involves three tasks.

- Document the responsibilities of divisions, departments and individual managers.

- Prepare responsibility charts for managers at divisional, departmental and subordinate levels.

- Prepare activity schedules for managers at divisional, departmental and subordinate levels.

Responsibility charts

Responsibility charts can be drawn up for management at all levels in the organisation, including the board of directors. They show the control points that indicate what needs to be achieved and how to recognise when things are going wrong. For each manager, a responsibility chart will have four main elements.

- The manager’s major objective

- The manager’s general programme for achieving that objective

- Sub-objectives

- Critical assumptions underlying the objectives and the programme

Example: responsibility charts for marketing director

- Major objective and general programme: to achieve a targeted level of sales, by selling existing well-established products, by breaking into new markets and by a new product launch

- Sub-objectives: details of the timing of the product launch; details and timing of promotions, advertising campaigns and so on

- Critical assumptions: market share, market size, competitors’ activity and so on

Activity schedules

Successful implementation of corporate plans also means getting activities started and completed on time. Every manager should have an activity schedule in addition to his responsibility chart, which identifies what activities he must carry out and the start-up and completion dates for each activity.

Critical dates might include equipment installation dates and product launch dates. In some markets, the launch date for a new product or new model can be extremely important, with an aim to gain maximum exposure for the product at a major trade fair or exhibition. New car models must be ready for a major motor show, for example. If there is a delay in product launch there might be a substantial loss of orders which the trade fair could have generated.

Consequently, to ensure co-ordination, the various functional objectives must be interlocked.

- Vertically from top to bottom of the business.

- Horizontally, for example, the objectives of the production function must be linked with those of sales, warehousing, purchasing, R&D and so on.

- Over time. Short-term objectives can be regarded as intermediate milestones on the road towards long-term objectives

Hierarchy of objectives

The hierarchy of objectives which emerges is this.

Mission

Goals

Objectives

Increasing coverage of

Strategy aspects of the organisation

Tactics

Operational plans

Objectives are normally established within this hierarchical structure. Each level of the hierarchy derives its objectives from the level above, so that all ultimately are founded in the organisation’s mission. Objectives therefore cascade down the hierarchy so that, for example, strategies are established to achieve objectives and they, in turn, provide targets for the purposes of tactical planning

SOCIAL AND ETHICAL OBLIGATIONS

Goals and objectives are often set with stakeholders in mind. For a business, adding value for shareholders is a prime corporate objective, but other stakeholders need to be satisfied. There is no agreement as to the extent of the social or ethical responsibilities of a business.

Public opinion and attitudes, and legal and political pressures, mean that organisations can no longer concentrate solely on financial corporate objectives. Environmental and social obligations now play a part in shaping an organisation’s objectives.

Stakeholder approach

An organisation’s stakeholders have a significant impact on its social and ethical obligations.

Stakeholders are groups of people or individuals who have a legitimate interest in the activities of an organisation. They include customers, employees, the community, shareholders, suppliers and lenders.

There are three broad types of stakeholder in an organisation.

- Internal stakeholders (employees, management)

- Connected stakeholders (shareholders, customers, suppliers, financiers)

- External stakeholders (the community, government, pressure groups)

The stakeholder approach suggests that corporate objectives are, or should be, shaped and influenced by those who have sufficient involvement or interest in the organisation’s operational activities.

Internal stakeholders: employees and management

Because employees and management are so intimately connected with the company, their objectives are likely to have a strong influence on how it is run. They are interested in the following issues.

- The organisation’s continuation and growth. Management and employees have a special interest in the organisation’s continued existence.

- Managers and employees have individual interests and goals which can be harnessed to the goals of the organisation.

- Jobs/careers (iii) Benefits (v) Promotion

- Money (iv) Satisfaction

For managers and employees, an organisation’s social obligations will include the provision of safe working conditions and anti-discrimination policies

Connected stakeholders

Increasing shareholder value should assume a core role in the strategic management of a business. If management performance is measured and rewarded by reference to changes in shareholder value then shareholders will be happy, because managers are likely to encourage long-term share price growth.

| Connected stakeholder | Interests to defend |

| Shareholders (corporate strategy) | • Increase in shareholder wealth, measured by profitability, P/E ratios, market capitalisation, dividends and yield • Risk |

| Bankers (cash flows) | • Security of loan • Adherence to loan agreements |

| Suppliers (purchase

strategy) |

• Profitable sales • Long-term relationship

• Payment for goods |

| Customers (product

market strategy) |

• Goods as promised • Future benefits |

Even though shareholders are deemed to be interested in return on investment and/or capital appreciation, many want to invest in ethically-sound organisations.

External stakeholders

External stakeholder groups – the government, local authorities, pressure groups, the community at large, professional bodies – are likely to have quite diverse objectives.

| External stakeholder | Interests to defend |

| Government | • Jobs, training, tax revenues |

| Interest/pressure groups / charities / ‘civil society’ | • Pollution • Rights • Other

|

It is external stakeholders in particular who induce social and ethical obligations.

Social responsibility

Why should organisations play an active social role in the society within which they function?

- ‘The public’ is a stakeholder in the business. A business only succeeds because it is part of a wider society. Giving to charity is one way of enhancing the reputation of the business.

- Charitable donations and artistic sponsorship are a useful medium of public relations and can reflect well on the business.

- Involving managers and staff in community activities is good work experience.

- It helps create a value culture in the organisation and a sense of mission, which is good for motivation.

- In the long term, upholding the community’s values, responding constructively to criticism, contributing towards community well-being might be good for business, as it promotes the wider environment in which businesses flourish.

- There is increasing political pressure on businesses to be socially responsible. Such activities help ‘buy off’ environmentalists.

Case Study

Arriva plc

Arriva plc (Arriva was acquired by Deutsche Bahn of Germany in 2010) operated bus and train services in the UK and Europe. It had a revenue of $1.6bn and 33,000 employees. Here is an extract from its 2005 accounts.

‘A community focus

We know that we are an important part of the communities we serve. By the very nature of our business, we have a responsibility to these communities across the UK and mainland Europe. For that reason, our community relations activities are at the heart of our commitment to corporate responsibility. Our Community Relations Committee, which is chaired by an executive director, Steve Clayton, includes representatives from across the Group and it continues to work towards the vision we established in 2004: ‘As a people business, we value, encourage and celebrate the contribution our employees and others make to the communities we serve.’ Arriva has worked hard to establish a series of long-term partnerships giving not only financial, but also practical support. One such partnership is with Age Concern. As part of this developing partnership, in 2004 we supported Age Concern’s information technology (IT) project in Hertfordshire to help older people take part in computer training. A facility was established to help them use IT in a number of areas, including keeping in touch with family and friends, finding out information such as bus and train timetables and ordering shopping for home delivery. Arriva’s support has meant that this project was able to continue throughout 2005. We have joined forces with the Wales Deaf Rugby Union as official sponsor of the team in another successful partnership. In addition to supporting the development of deaf rugby in communities right across Arriva’s rail network, the partnership is also helping us to understand better the needs of people who are hard of hearing and ensure we offer the best possible service to all our customers.

Employees in the Community

Our employees are involved in our Community Relations Programme and vote each year for their ‘Charity of the Year’ for the UK. This has been running for six years and provides employees with the opportunity to select a charity that they would like the Group to support for 12 months. Our employees voted for Cancer Research UK as the 2006 Charity of the Year for the third year running. In the Netherlands, some of the charities we have supported during 2005 include ‘Doo een Wens’, the Dutch Make a Wish Foundation whose aim is to grant the wishes of children with life-threatening illnesses around the world; ‘Cool Flevoland’, a youth panel initiative which aims to improve young people’s interest in politics and social themes, and ‘Dance4Life’ which has been set up by young people to fight the spread of Aids. Many of our employees across the UK and mainland Europe make valuable contributions to their local communities outside of their working life with Arriva. We value this and we recognise many of their efforts through our Community Action Awards. Employees are encouraged to tell us about their charitable work. In return, they are put forward for consideration of an award, which is donated to the organisation they support. In 2005, we presented 57 cash awards to our employees for their chosen causes.

Business in the Community

We are a national member of Business in the Community (BITC) and we actively support some of its initiatives. BITC is a charitable organisation which helps businesses contribute to the social and economic regeneration of local communities. During 2005, Arriva employees from the north east of England took part in a reading programme with a local primary school, which selected pupils it felt would benefit from extra support. They listened to the children read and helped with the reading process. The project proved enjoyable and worthwhile for both the children and volunteers. We were also named as one of BITC’s top ten overall performers in the Race for Opportunity awards. This recognises efforts that organisations make to ensure that their workforce is diverse and that differences are valued and understood.’

There are three contrasting views about a corporation’s responsibilities.

- If the company creates a social problem, it must fix it (eg Exxon (see below)).

- The multinational corporation has the resources to fight poverty, illiteracy, malnutrition, illness and so on. This approach disregards who actually creates the problem.

Case Study

Such an approach dates back to Henry Ford, who said ‘I do not believe that we should make such an awful profit on our cars. A reasonable profit is right, but not too much. So it has been my policy to force the price of the car down as fast as production would permit, and give the benefits to the users and the labourers, with surprisingly enormous benefits to ourselves.’

Companies already discharge their social responsibility, simply by increasing their profits and thereby contributing more in taxes. If a company was expected to divert more resources to solve society’s problems, this would represent a double tax.

The social audit

Social audits involve five key elements.

- Recognising a firm’s rationale for engaging in socially responsible activity

- Identification of programmes which are congruent with the mission of the company

- Determination of objectives and priorities related to this programme

- Specification of the nature and range of resources required

- Evaluation of company involvement in such programmes past, present and future

Whether or not a social audit is used depends on the degree to which social responsibility is part of the corporate philosophy.

Case Study

In the USA, social audits on environmental issues have increased since the Exxon Valdez catastrophe in 1989 in which millions of gallons of crude oil were released into Alaskan waters.

Conclusion

The importance of corporate social responsibility reporting is evident from facts included in ‘How to be good’ by Cathy Hayward (Financial Management, October 2002).

- A Mori poll has found that [92 per cent of the British public believe that multinational companies should meet the highest human health, animal welfare and environmental standards wherever they are operating, and] that almost 90 per cent of British people believe the government should protect the environment, employment conditions and health even when this conflicts with the interests of multinationals.

- A survey by the National Union of Students in UK has shown that more than 75 per cent of student jobseekers would not work for an “ethically unsound” employer.’

Ethics and ethical conduct

Whereas social responsibility deals with the organisation’s general stance towards society, and affects the activities the organisation chooses to do, ethics relates far more to how an organisation conducts individual transactions.

We previously looked at the ethical issues that might impact on drawing up strategic plans as well as affecting performance. In this chapter we consider how ethical obligations should be considered when pursuing corporate objectives.

Organisations are coming under increasing pressure from a number of sources to behave more ethically.

- Government

- UK and European legislation

- Treaty obligations (such as the Kyoto Summit)

- Consumers

- Employers

- Pressure groups

These sources of pressure expect an ethical attitude towards the following.

- Stakeholders

- Animals

- Green issues (such as pollution and the need for re-cycling)

- The disadvantaged

- Dealings with unethical companies or countries

A clear example of unethical conduct is bribery.

- In some countries, government officials routinely demand bribes, to supplement their meagre incomes. For example customs officials demand ‘commission’ before releasing documentation enabling goods to move from the warehouse.

- More serious bribes occur when companies bid for large public sector contracts, and pay substantial amounts to politicians and key decision makers.

The boundary between dubious ethics and criminality has shifted over the years, particularly with increased standards of corporate governance. Insider dealing, whereby individuals benefit from unpublished information which may affect the share price, used to be normal practice (a perk of working in stock broking); now it is a crime.

Attitudes to corporate ethics

Reidenbach and Robin usefully distinguish between five different attitudes to corporate ethics. The following is an adapted version of a report in the Financial Times.

Amoral organisations

Such organisations are prepared to condone any actions that contribute to the corporate aims (generally the owner’s short-term greed). Getting away with it is the only criterion for success. Getting caught will be seen as bad luck. In a nutshell, there is no set of values other than greed. Obviously, this company gets away without a written code.

Legalistic organisations

Such organisations obey the letter of the law but not necessarily the spirit of it, if that conflicts with economic performance. Ethical matters will be ignored until they become a problem. Frequent problems would lead to a formal code of ethics that says, in effect, ‘Don’t do anything to harm the organisation’.

Responsive companies

These organisations take the view – perhaps cynically, perhaps not – that there is something to be gained from ethical behaviour. It might be recognised, for example, that an enlightened attitude towards staff welfare enabled the company to attract and retain higher calibre staff. If such a company has a formal code of ethics it will be one that reflects concern for all stakeholders in the business.

Emerging ethical (or ‘ethically engaged’) organisations

They take an active (rather than a reactive) interest in ethical issues.

‘Ethical values in such companies are part of the culture. Codes of ethics are action documents, and contain statements reflecting core values. A range of ethical support measures are normally in place, such as ethical review committees; hotlines; ethical audits; and ethics counsellors or ombudsmen.

Problem solving is approached with an awareness of the ethical consequence of an action as well as its potential profitability, and pains are taken to uphold corporate values.’

Ethical organisations

These organisations have a ‘total ethical profile’: a philosophy that informs everything that the company does and a commitment on the part of everyone to carefully selected core values.

Case Study

The Co-operative Bank (a mutual organisation and part of the Co-operative Group in the UK), which has a strong record of ethical reporting, publishes a partnership report. This is an independently-audited ethical and ecological health check that considers how the bank is meeting its obligations to customers, employees and their families, members, suppliers, local communities, national and international society and past and future generations.

According to an article in Financial Management (‘How to be good,’ Cathy Hayward, October 2002), the ethical and ecological positioning of the Co-operative bank contributed more than £20 million, or 20 per cent, of its profits in 2001. Almost a third of its current account customers (the bank’s key market) were with the bank primarily because of its ethical policies, according to a survey.

Corporate codes and corporate culture Case Study

The following extraxct is from a UK newspaper but is a good illustration:

‘Shocking tactics including bribery, fabrication and plagiarism are being used by unscrupulous drug companies to get their research published in influential medical journals, according to a damning new report.

Only a week after controversial research on the MMR (MMR = Measles, Mumps and Rubella) vaccine was discredited by the journal which published it following a ‘fatal conflict of interest’, an influential committee has revealed the widespread use of underhand tactics by researchers.

And the Committee on Public Ethics (COPE) is urging the editors of scientific journals to sign up to a new code of conduct aimed at preventing conflicts of interest and mistakes in published research.

The right kind of report appearing in a scientific journal can be worth millions of pounds for drug companies and manufacturers of medical equipment. In addition, industries such as tobacco, alcohol and health, and even junk foods, hope to cite studies masquerading as independent research in support of their products.

Articles in scientific journals can also be used to knock out competitors or quieten down public concern about controversial issues.

In one of the cases cited by the report a journal published a paper on passive smoking in which the authors failed to declare financial support from the tobacco industry.

On another occasion, a high-ranking government official telephoned an editor in an attempt to stop an article being written which was critical of some government research.

In one of the most disturbing examples, a team of scientists was forced to withdraw a paper after refusing to detail how they had been allowed to analyse blood taken from babies.

Tactics have also included bribery. On one occasion an editor was telephoned by a representative who said she would guarantee to buy 1,000 reprints if the journal would continue to consider for publication a study that conflicted with a policy the journal had just introduced. ‘And I will buy you a dinner at any restaurant you choose,’ added the representative.

Plagiarism is also seen as a growing problem in scientific papers, especially where Internet search engines allow researchers to cull information from other papers.

A spectacular example saw authors copy another study almost wholesale, but change the number of patients, the type of surgery, the regimen of one of the drugs and add data for another drug.

‘If we don’t have strict ethics, how can we trust medical research?’

The revelations follow the controversy surrounding Dr Andrew Wakefield’s work on the MMR vaccine, published in the Lancet in 1998. It emerged 10 days ago that Wakefield had been looking for evidence to support a legal action by parents claiming the vaccine had harmed their children at the same time.

The research, linking MMR to autism in children, sparked a major controversy and led to large numbers of parents refusing to allow their children to be treated with the jab.

Lancet editor Dr Richard Horton said the situation represented a ‘fatal conflict of interest’ and called into question whether Wakefield’s paper should have been published.

His comments came as the General Medical Council prepared to open an investigation into the way Wakefield carried out his study.

Last week, Sir Liam Donaldson, England’s chief medical officer, accused Wakefield of peddling ‘poor science’. Wakefield has insisted he has done nothing wrong and says the science behind his study still stands.

COPE, which represents more than 178 editors around the world, is now publishing a guide for the editors of science publications. It puts them under an obligation to ensure the accuracy of the material they publish, maintain scientific integrity and ensure business needs do not compromise intellectual standards.

Editors are also asked to be willing to correct, clarify and retract material or issue apologies when necessary.

The new code warns them that they can be held responsible for publishing ‘unethical’ research. It advises that systems should be in place for managing conflicts of interest relating to journal editors, their staff, authors and the reviewers who vet papers before they are published.

The code was drafted by Dr Richard Smith, editor of the British Medical Journal – the Lancet’s main rival.

He said: ‘Like everybody else we are much more interested in other people’s accountability than we are our own. Editors are peculiarly unaccountable because of their traditions of editorial freedom, and there are no bodies that attempt to regulate medical and scientific editors.’

A spokeswoman for the Medical Research Council said: ‘We in no way ever approve of such tactics to get research approved. We expect scientists to abide by the highest ethical standards in their work.’

Bill O’ Neill, the Scottish secretary of the British Medical Association, said: ‘I don’t think anyone would question the need for strict rules. If we don’t have rigorous ethics then how can we trust research?’

Source: Scotsman News,March 2004

Many commentators would argue that the introduction of a code of ethics is inadequate on its own. To be effective a code needs to be accompanied by positive attempts to foster guiding values, aspirations and patterns of thinking that support ethically sound behaviour – in short a change of culture.

Increasingly organisations are responding to this challenge by devising ethics training programmes for the entire workforce, instituting comprehensive procedures for reporting and investigating ethical concerns within the company, or even setting up an ethics office or department to supervise the new measures. About half of all major companies now have a formal code of some kind.

Lynne Paine (Harvard Business Review, March – April 1994) suggests that ethical decisions are becoming more important as, in the US at least, penalties for companies which break the law are becoming tougher. Paine describes two approaches to the management of ethics in organisations.

- A compliance-based approach is primarily designed to ensure that the company and its personnel act within the letter of the law. Mere compliance is not an adequate means for addressing the full range of ethical issues that arise every day.

- An integrity-based approach combines a concern for the law with an emphasis on managerial responsibility for ethical behaviour. When integrated into the day-to-day operations of an organisation, such strategies can help prevent damaging ethical lapses.

It would seem to follow that the imposition of social and ethical responsibilities on management should come from within the organisation itself, and that the organisation should issue its own code of conduct for its employees.

Code of conduct

A corporate code typically contains a series of statements setting out the company’s values and explaining how it sees its responsibilities towards stakeholders.

The impact of a corporate code

A code of conduct can set out the company’s expectations, and in principle a code may address many of the problems that the organisations may experience. However, merely issuing a code is not enough.

- The commitment of senior management to the code needs to be real, and it needs to be very clearly communicated to all staff. Staff need to be persuaded that expectations really have changed.

- Measures need to be taken to discourage previous behaviours that conflict with the code.

- Staff need to understand that it is in the organisation’s best interests to change behaviour, and become committed to the same ideals.

- Some employees – including very able ones – may find it very difficult to buy into a code that they perceive may limit their own earnings and/or restrict their freedom to do their job.

- In addition to a general statement of ethical conduct, more detailed statements (codes of practice) will be needed to set out formal procedures that must be followed.

Case Study

An extract from Google’s Code of Conduct

‘Our informal corporate motto is ‘Don’t be evil’. We Googlers generally relate those words to the way we serve our users – as well we should. But being ‘a different kind of company’ means more than the products we make and the business we’re building; it means making sure that our core values inform our conduct in all aspects of our lives as Google employees.

The Google Code of Conduct is the code by which we put those values into practice. This document is meant for public consumption, but its most important audience is within our own walls. This code isn’t merely a set of rules for specific circumstances but an intentionally expansive statement of principles meant to inform all our actions; we expect all our employees, temporary workers, consultants, contractors, officers and directors to study these principles and do their best to apply them to any and all circumstances which may arise.

The core message is simple: being Googlers means striving toward the highest possible standard of ethical business conduct. This is a matter as much practical as ethical; we hire great people who work hard to build great products, but our most important asset by far is our reputation as a company that warrants our users’ faith and trust. That trust is the foundation upon which our success and prosperity rests, and it must be re-earned every day, in every way, by every one of us.

So please do read this code, and then read it again, and remember that as our company evolves, The Google Code of Conduct will evolve as well. Our core principles won’t change, but the specifics might, so a year from now, please read it a third time. And always bear in mind that each of us has a personal responsibility to do everything we can to incorporate these principles into our work, and our lives.’

THE SHORT TERM AND LONG TERM

The S/L trade-off refers to the balance of organisational activities aiming to achieve longterm and short-term objectives when they conflict or where resources are scarce.

Long-term and short-term objectives

Objectives may be long term and short term.

For example, a company’s primary objective might be to increase its earnings per share from RWF300 to RWF500 in the next five years. A number of strategies for achieving the objective might then be selected.

-

- Increasing profitability in the next twelve months by cutting expenditure

- Increasing export sales over the next three years

- Developing a successful new product for the domestic market within five years

Secondary objectives might then be re-assessed to include the following.

-

- The objective of improving manpower productivity by 10% within twelve months.

- Improving customer service in export markets with the objective of doubling the number of overseas sales outlets in selected countries within the next three years.

- Investing more in product-market research and development, with the objective of bringing at least three new products to the market within five years.

Targets cannot be set without an awareness of what is realistic. Quantified targets for achieving the primary objective, and targets for secondary objectives, must therefore emerge from a realistic ‘position audit’.

Trade-offs between short-term and long-term objectives

Just as there may have to be a trade-off between different objectives, so too might there be a need to make trade-offs between short-term objectives and long-term objectives. This is referred to as S/L trade-off.

The S/L trade-off refers to the balance of organisational activities aiming to achieve long term and short-term objectives when they are in conflict or where resources are scarce.

Some decisions involve the sacrifice of longer-term objectives.

- Postponing or abandoning capital expenditure projects, which would eventually contribute to growth and profits, in order to protect short term cash flow and profits.

- Cutting R&D expenditure to save operating costs, and so reducie the prospects for future product development.

- Reducing quality control, to save operating costs (but also adversely affect reputation and goodwill).

- Reducing the level of customer service, to save operating costs (but sacrifice goodwill).

- Cutting training costs or recruitment (so the company might be faced with skills shortages).

Steps that could be taken to control S/L trade-offs, so that the ‘ideal’ decisions are taken, include the following.

- Making short-term targets realistic. If budget targets are unrealistically tough, a manager will be forced to make S/L trade-offs.

- Providing sufficient management information to allow managers to see what tradeoffs they are making. Managers must be kept aware of long-term aims as well as shorter-term (budget) targets.

- Evaluating managers’ performance in terms of contribution to long-term as well as short-term objectives.

THE PLANNING GAP AND STRATEGIES TO FILL IT

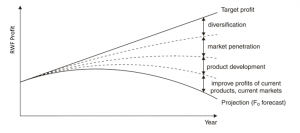

Forecasts based on current performance may reveal a gap between the firm’s objectives and the likely outcomes. New strategies (e.g. market penetration, market development, product development, diversification, withdrawal) are developed to fill the gap.

Strategic planners need to consider the extent to which new strategies are needed to enable the organisation to achieve its objectives. One technique whereby this can be done is gap analysis.

Gap analysis

Gap analysis involves comparing an organisation’s ultimate objective (most commonly expressed in terms of demand, but may be reported in terms of profit, ROCE and so on) and the expected performance of planned and current projects.

Purpose of gap analysis

- Determine the organisation’s targets for achievement over the planning period

- Establish what the organisation would be expected to achieve if it ‘did nothing’ (did not develop any new strategies, but simply carried on in the current way with the same products and selling to the same markets)

This difference is the ‘gap’. New strategies will then have to be developed which will close this gap, so that the organisation can expect to achieve its targets over the planning period. We cover these strategies below.

The planning gap is not the gap between the current position of the organisation and the forecast desired position.

Rather, it’s the gap between the forecast position from continuing with current activities, and the forecast of the desired position.

A forecast based on doing nothing will probably provide an unrealistic estimate of future performance, but it is useful.

- The forecast is used to determine the requirement for new strategies and so it must exclude such strategies.

- Including the impact of strategies of which the organisation has little or no experience will produce an even more inaccurate forecast.

- It reduces the complexity involved in the forecasting exercise.

- It provides an assessment of what could be achieved without taking on new risk.

Forecasts must cover a period far enough into the future to reveal any significant gap. How far ahead an organisation needs to plan, however, will depend on the lead time for corrective action to take effect, which in turn depends on the nature of the organisation’s business and the type of action required.

Closing the gap with product-market strategies

A product-market strategy considers the mix of products and markets. The aim of such strategies is to close the gap found by gap analysis.

Product-market mix is a short hand term for the products/services a firm sells (or a service which a public sector organisation provides) and the markets it sells them to.

Product-market mix: Ansoff’s growth vector matrix

The Ansoff matrix identifies various options.

- Market penetration: current products, current markets

- Market development: current products, new markets

- Product development: new products, current markets

- Diversification: new products, new markets

All of these can secure growth.

Igor Ansoff drew up a growth vector matrix, describing how a combination of a firm’s activities in current and new markets, with existing and new products, can lead to growth. Ansoff’s original model was a four cell matrix based on product and market.

We look at Ansoff’s matrix in more detail in Study Unit 21. All you need to know here is that the matrix is used to indicate strategies for closing the gap found by gap analysis.

Closing the profit gap and product-market strategy

The aim of product-market strategies is to close the profit gap that is found by gap analysis. A mixture of strategies may be needed to do this.

It is worth remembering that divestment is a product-market option to close the profit gap, if the business is creating losses.

A related question is what do you do with spare capacity – go for market penetration, or go into new markets. Many companies begin exporting into new overseas markets to use surplus capacity.

The strategies in the Ansoff matrix are not mutually exclusive. A firm can quite legitimately pursue a penetration strategy in some of its markets, while aiming to enter new markets.

OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Operations can make or break strategies. They are directly focused on value-adding activities.

The Study Guide requires you to ‘identify and discuss the characteristics of operational performance’.

Operations are the day to day activities that are carried out in order to achieve specific targets and objectives. Here are some examples.

| Sector | Operations carried out by … |

| Fast-food | Staff employed at a McDonald’s checkout |

| Bank | Dealer on the Forex markets |

| Law | Solicitor finalising the details of a contract for a client |

| Call centre | People hosting the switch board |

| Media | TV camera-person, or presenter Website construction |

| Manufacturing | Assembly line worker |

| Construction | Building site operations |

These examples show that operations are directly focused on activities which immediately add value to the customer.

Unlike strategy, which involves taking decisions, operations have the following characteristics.

- Customer-facing, in service industries

- Specialised, as the tasks are closely defined

- More likely to be routine, but this is not true of all ‘operations’

- Limited in scope

- Characterised by short time horizons

- Easier to automate than some management tasks

The significance of operations

- Many operational activities require expert or specialised skills – such as surgery.

- Operations can be areas of significant risk for a company and its customers.

- Operations are ‘moments of truth’ between the firm and its customers. A company’s reputation can be made or broken by the quality of its goods and services, which are determined by operational quality and consistency.

- The operational infrastructure comprises the most significant element of cost for most businesses.

- The most well-designed strategy can be destroyed by poor implementation at operational level.

- Operations and the deployment of operational activities are a key determinant of organisation structure.

PLANNING AND CONTROL AT DIFFERENT LEVELS IN THE PERFORMANCE HIERARCHY

Planning and control occurs at all levels of the performance hierarchy to different degrees.

Planning

Although it implies a ‘top down’ approach to management, we could describe a cascade of goals, objectives and plans down through the layers of the organisation. The plans made at the higher levels of the performance hierarchy provide a framework within which the plans at the lower levels must be achieved. The plans at the lower levels are the means by which the plans at the higher levels are achieved.

It could therefore be argued that without the plans allied directly to the vision and corporate objective the operational-level and departmental plans have little meaning. Planning could therefore be deemed as more significant at the higher levels of the performance hierarchy than the lower levels.

This is not to say that planning at an operational level is not important. It is just that the two types of planning are different.

| Level | Detail | |

| Corporate plans | •

• |

Focused on overall performance Environmental influence |

| • | Set plans and targets for units and departments | |

| • | Sometimes qualitative (e.g. a programme to change the culture of the organisation) | |

| • | Aggregate | |

| Operational plans | • • |

Based on objectives about ‘what’ to achieve

Specific (e.g. acceptable number of ‘rings’ before a phone is answered) |

| • | Little immediate environmental influence | |

| • | Likely to be quantitative | |

| • | Detailed specifications | |

| • | Based on ‘how’ something is achieved | |

| • | Short time horizons |

Control

Consider how the activities of planning and control are inter-related.

- Plans set the targets.

- Control involves two main processes.

- Measure actual results against the plan.

- Take action to adjust actual performance to achieve the plan or to change the plan altogether.

Control is therefore impossible without planning.

The essence of control is the measurement of results and comparing them with the original plan. Any deviation from plan indicates that control action is required to make the results conform more closely with plan.

Feedback

Feedback occurs when the results (outputs) of a system are used to control it, by adjusting the input or behaviour of the system.

A business organisation uses feedback for control.

- Negative feedback indicates that results or activities must be brought back on course, as they are deviating from the plan.

- Positive feedback results in control action continuing the current course. You would normally assume that positive feedback means that results are going according to plan and that no corrective action is necessary: but it is best to be sure that the control system itself is not picking up the wrong information.

- Feedforward control is control based on forecast results: in other words if the forecast is bad, control action is taken well in advance of actual results.

There are two types of feedback.

- Single loop feedback is control, like a thermostat, which regulates the output of a system. For example, if sales targets are not reached, control action will be taken to ensure that targets will be reached soon. The plan or target itself is not changed, even though the resources needed to achieve it might have to be reviewed.

- Double loop feedback is of a different order. It is information used to change the plan itself. For example, if sales targets are not reached, the company may need to change the plan.

Control at different levels

You might think that control can only occur at the lower-levels of the performance hierarchy, as that is the type of control you have encountered in your studies to date (standard costing, budgetary control). Such control has the following features.

- Exercised externally by management or, in the case of empowered teams, by the staff themselves

- Immediate or rapid feedback

- Single loop feedback (i.e. little authority to change plans or targets)

Control does occur at the higher-levels of the hierarchy, however, and has the following characteristics.

- Exercised by external stakeholders (e.g. shareholders)

- Exercised by the market

- Double loop feedback (i.e. relatively free to change targets)

- Often feedforward elements

Summary

The best way to envisage the differences is by two case examples.

Case Study

Call centres

Staff who in call centres are subject to precise controls and targets.

- The longest time a phone should ring before it is answered

- Speed of dealing with the caller’s query

- Rehearsal of a ‘script’, or use of precise responses or prompts from software

Staff who take too long dealing with queries may be counselled or dismissed.

The targets are precisely and exactly linked to the service provided and provide rapid feedback. Control and planning is exercised over the process of delivery.

Senior management

Senior management initiate the planning process, but their time is planned to a far less rigid degree than people at operational level.

For example, the Chief Executive of Network Rail in the UK is responsible to shareholders but, given the nature of the industry and its reliance on UK government subsidies, must also be accountable to other stakeholders. The market is mainly concerned with results. Controls over corporate governance – over how the company is run – are mainly to do with ensuring the transparency and integrity of the governance process.

CHAPTER ROUNDUP

- Vision is oriented towards the future, to give a sense of direction to the organisation. Mission describes an organisation’s basic purpose, what it is trying to accomplish.

- A mission statement should be brief, flexible and distinctive, and is likely to place an emphasis on serving the customer.

- Goals and objectives are set out to give flesh to the mission in any particular period.

- Goals can be set in many different ways: top down; bottom up; imposed; consensus; precedent.

- Corporate objectives concern the firm as a whole. Unit objectives are specific to individual units of an organisation.

- Primary corporate objectives are supported by secondary objectives, for example for product development or market share. In practice there may be a trade-off between different objectives.

- Goals and objectives are often set with stakeholders in mind. For a business, adding value for shareholders is a prime corporate objective, but other stakeholders need to be satisfied. There is no agreement as to the extent of the social or ethical responsibilities of a business.

- The S/L trade-off refers to the balance of organisational activities aiming to achieve long-term and short-term objectives when they conflict or where resources are scarce.

- Forecasts based on current performance may reveal a gap between the firm’s objectives and the likely outcomes. New strategies (eg market penetration, market development, product development, diversification, withdrawal) are developed to fill the gap.

- A product-market strategy considers the mix of products and markets. The aim of such strategies is to close the gap found by gap analysis.

- The Ansoff matrix identifies various options.

- Market penetration: current products, current markets

- Market development: current products, new markets

- Product development: new products, current markets

- Diversification: new products, new markets

All of these can secure growth.

- Operations can make or break strategies. They are directly focused on value-adding activities.

- Planning and control occurs at all levels of the performance hierarchy to different degrees.