OBJECTIVES

Corporate objectives concern the firm as a whole. Unit objectives are specific to individual units, divisions or functions of an organisation.

Corporate objectives are set as part of the corporate planning process which is concerned with the selection of strategies which will achieve the corporate objectives of the organisation.

Corporate objectives versus unit objectives

Corporate objectives should relate to the key factors for business success.

- Profitability Customer satisfaction

- Market share Quality

- Growth Industrial relations

- Cash flow Added value

- Return on capital employed Earnings per share

- Risk

Unit objectives, on the other hand, are specific to individual business units, divisions or functions of an organisation.

| Types | Examples |

| Commercial | • Increase the number of customers by x% (an objective of a sales department)

• Reduce the number of rejects by 50% (an objective of a production department) • Produce monthly reports more quickly, within 5 working days of the end of each month (an objective of the finance & management accounting departments) |

| Public sector | • Introduce x% more places at nursery schools (an objective of a district education department)

• Respond more quickly to calls (an objective of a local police station, fire department or even a telephone-banking help-line) |

| General | • Resources (e.g. cheaper raw materials, lower borrowing costs, ‘topquality’ accountants)

• Market (e.g. market share, market standing) • Employee development (e.g. training, promotion, safety) • Innovation in products or processes • Productivity (the amount of output from resource inputs) • Technology |

Primary and secondary objectives

Primary corporate objectives are supported by secondary objectives, for example for product development or market share. In practice there may be a trade off between different objectives.

An organisation has many objectives. It has been argued that there is a limit to the number of objectives that a manager can pursue effectively. Too many and the manager cannot give adequate attention to each and/or the focus may inadvertently be placed on minor ones. Some objectives are more important than others. It has therefore been suggested that there should be one primary corporate objective (restricted by certain constraints on corporate activity) and other secondary objectives. These are strategic objectives which should combine to ensure the achievement of the primary corporate objective.

- For example, if a company sets itself a primary objective of growth in profits, it will then have to develop strategies by which this primary objective can be achieved.

- Secondary objectives might then be concerned with sales growth, continual technological innovation, customer service, product quality, efficient resource management (e.g. labour productivity) or reducing the company’s reliance on debt capital.

Conflicting objectives

Corporate objectives may conflict with divisional objectives in large organisations. A danger is that the organisation will divide into a number of self-interested segments, each acting at times against the wishes and interests of other segments. Decisions might be taken by a divisional manager in the best interests of his own part of the business, but possibly against the interests of the organisation as a whole. The setting of objectives is very much a political process: objectives are formulated following bargaining by the various interested parties whose requirements may conflict. Such conflict may be resolved via prioritisation, compromise, negotiation and satisficing (satisfy and suffice).

- Prioritisation is where certain goals get priority over others. This is usually determined by senior managers but there can be quite complicated systems to rank goals and strategies according to certain criteria.

- Negotiation is the bargaining process that occurs at each stage of the budgeting process. This allows full participation to take place by all budget holders. Any revisions to the budget must be after giving full consideration to arguments for including any of the budgeted items.

- Compromise is the central aspect of any process of negotiation where there is disagreement. It can be seen as positive where both parties win something but also negative where both parties give something away.

- Satisficing occurs when a satisfactory and sufficient solution rather than an optimum solution is found. Organisations may not aim to maximise performance in one area if

this leads to poor performance elsewhere. Rather they will accept satisfactory, if not excellent performance in a number of areas.

Goal congruence exists when managers working in their best interests also act in harmony with the goals of the organisation as a whole. This is not easy to achieve and a budgetary control system needs to be designed to evoke the required behaviour.

THE PLANNING AND CONTROL CYCLE

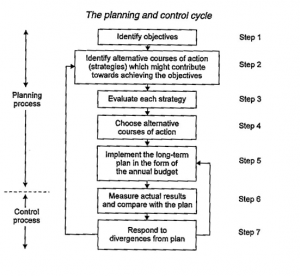

The planning and control cycle has seven steps.

- Step 1. Identify objectives

- Step 2. Identify potential strategies

- Step 3. Evaluate strategies

- Step 4. Choose alternative courses of action

- Step 5. Implement the long-term plan

- Step 6. Measure actual results and compare with the plan

- Step 7. Respond to divergences from the plan

The diagram below represents the planning and control cycle. The first five steps cover the planning process. Planning involves making choices between alternatives and is primarily a decision-making activity. The last two steps cover the control process, which involves measuring and correcting actual performance to ensure that the alternatives that are chosen and the plans for implementing them are carried out.

| Step 1 | Identify objectives

Objectives establish the direction in which the management of the organisation wishes it to be heading. They answer the question: ‘where do we want to be?’

|

| Step 2 | Identify potential strategies

Once an organisation has decided ‘where it wants to be’, the next step is to identify a range of possible courses of action or strategies that might enable the organisation to get there. The organisation must therefore carry out an information-gathering exercise to ensure that it has a full understanding of where it is now. This is known as a ‘position audit‘ or ‘strategic analysis‘ and involves looking both inwards and outwards. a) The organisation must gather information from all of its internal parts to find out what resources it possesses: what its manufacturing capacity and capability are, what is the state of its technical know-how, how well it is able to market itself, how much cash it has in the bank and so on. b) It must also gather information externally so that it can assess its position in the environment. Just as it has assessed its own strengths and weaknesses, it must do likewise for its competitors (threats). Current and potential markets must be analysed to identify possible new opportunities. The ‘state of the world’ must be considered. Is it in recession or is it booming? What is likely to happen in the future? This part of the analysis is known as SWOT analysis – Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats. Having carried out a strategic analysis, alternative strategies can be identified. An organisation might decide to be the lowest cost producer in the industry, perhaps by withdrawing from some markets or developing new products for sale in existing markets. This may involve internal development or a joint venture.

|

| Step 3 | Evaluate strategies |

The strategies must then be evaluated in terms of suitability, feasibility and acceptability. Management should select those strategies that have the greatest potential for achieving the organisation’s objectives.

| Step 4 | Choose alternative courses of action

The next step in the process is to collect the chosen strategies together and coordinate them into a long-term financial plan. Typically this would show the following. • Projected cash flows • Capital expenditure plans • Projected long-term profits • Balance sheet forecasts • A description of the long-term objectives and strategies in words

|

| Step 5 | Implement the long-term plan

The long-term plan should then be broken down into smaller parts. It is unlikely that the different parts will fall conveniently into successive time periods. Strategy A may take two and a half years, while Strategy B may take five months, but not start until year three of the plan. It is usual, however, to break down the plan as a whole into equal time periods (usually one year). The resulting short-term plan is called a budget.

|

| Step 6 | Measure actual results and compare with plan

Actual results are recorded and analysed and information about actual results is fed back to the management concerned, often in the form of accounting reports. This reported information is feedback (see section named ‘Feedback’ below).

|

| Step 7 | Respond to divergences from plan |

By comparing actual and planned results, management can then do one of three things, depending on how they see the situation.

- They can take control action. By identifying what has gone wrong, and then finding out why, corrective measures can be taken.

- They can decide to do nothing. This could be the decision when actual results are going better than planned, or when poor results were caused by something which is unlikely to happen again in the future.

| Level | Detail | |

| Corporate plans | • | Focused on overall performance |

| • | Environmental influence | |

| • | Set plans and targets for units and departments | |

| • | Sometimes qualitative (e.g. a programme to change the culture of the organisation) | |

| • | Aggregate | |

| Operational plans | • • |

Based on objectives about ‘what’ to achieve

Specific (e.g. acceptable number of ‘rings’ before a phone is answered) |

| • | Little immediate environmental influence | |

| • | Likely to be quantitative | |

| • | Detailed specifications | |

| • | Based on ‘how’ something is achieved | |

| • | Short time horizons |

They can alter the plan or target if actual results are different from the plan or target, and there is nothing that management can do (or nothing, perhaps, that they want to do) to correct the situation.

Control

Consider how the activities of planning and control are inter-related.

- Plans set the targets.

- Control involves two main processes.

- Measure actual results against the plan.

- Take action to adjust actual performance to achieve the plan or to change the plan altogether.

Control is therefore impossible without planning.

The essence of control is the measurement of results and comparing them with the original plan. Any deviation from plan indicates that control action is required to make the results conform more closely with plan.

Feedback

Feedback occurs when the results (outputs) of a system are used to control it, by adjusting the input or behaviour of the system.

A business organisation uses feedback for control.

- Negative feedback indicates that results or activities must be brought back on course, as they are deviating from the plan.

- Positive feedback results in control action continuing the current course. You would normally assume that positive feedback means that results are going according to plan and that no corrective action is necessary: but it is best to be sure that the control system itself is not picking up the wrong information.

- Feedforward control is control based on forecast results: in other words if the forecast is bad, control action is taken well in advance of actual results.

There are two types of feedback.

- Single loop feedback is control, like a thermostat, which regulates the output of a system. For example, if sales targets are not reached, control action will be taken to ensure that targets will be reached soon. The plan or target itself is not changed, even though the resources needed to achieve it might have to be reviewed.

- Double loop feedback is of a different order. It is information used to change the plan itself. For example, if sales targets are not reached, the company may need to change the plan.

Control at different levels

Budgetary control occurs at the lower levels of the performance hierarchy.

Control at the lower-levels of the performance hierarchy, such as standard costing, and budgetary control has the following features.

- Exercised externally by management or, in the case of empowered teams, by the staff themselves

- Immediate or rapid feedback

- Single loop feedback (i.e. little authority to change plans or targets)

Control does also occur at the higher-levels of the hierarchy, however, and has the following characteristics.

- Exercised by external stakeholders (e.g. shareholders)

- Exercised by the market

- Double loop feedback (i.e. relatively free to change targets)

- Often feed forward elements

OBJECTIVES OF BUDGETARY SYSTEMS

Here are the objectives of a budgetary planning and control system.

- Ensure the achievement of the organisation’s objectives

- Compel planning

- Communicate ideas and plans

- Coordinate activities

- Provide a framework for responsibility accounting

- Establish a system of control

- Motivate employees to improve their performance

A budgetary planning and control system is essentially a system for ensuring communication, coordination and control within an organisation. Communication, coordination and control are general objectives: more information is provided by an inspection of the specific objectives of a budgetary planning and control system.

| Objective | Comment |

| Ensure the achievement of the organisation’s objectives | Objectives are set for the organisation as a whole and for individual departments and operations within the organisation. Quantified expressions of these objectives are then drawn up as targets to be achieved within the timescale of the budget plan. |

| Compel planning | This is probably the most important feature of a budgetary planning and control system. Planning forces management to look ahead, to set out detailed plans for achieving the targets for each department, operation and (ideally) each manager and to anticipate problems. It thus prevents management from relying on ad hoc or uncoordinated planning which may be detrimental to the performance of the organisation. |

| Communicate ideas and plans |

A formal system is necessary to ensure that each person affected by the plans is aware of what he or she is supposed to be doing. Communication might be one-way, with managers giving orders to subordinates, or there might be a two-way dialogue and exchange of ideas. |

| Coordinate activities | The activities of different departments or sub-units of the organisation need to be coordinated to ensure maximum integration of effort towards common goals. This concept of |

| Objective | Comment |

| coordination implies, for example, that the purchasing department should base its budget on production requirements and that the production budget should in turn be based on sales expectations. Although straightforward in concept, coordination is remarkably difficult to achieve, and there is often ‘sub-optimality’ and conflict between departmental plans in the budget so that the efforts of each department are not fully integrated into a combined plan to achieve the company’s best targets. | |

| Provide a framework for responsibility accounting | Budgetary planning and control systems require that managers of budget centres are made responsible for the achievement of budget targets for the operations under their personal control. |

| Establish a system of control | A budget is a yardstick against which actual performance is measured and assessed. Control over actual performance is provided by the comparisons of actual results against the budget plan. Departures from budget can then be investigated and the reasons for the departures can be divided into controllable and uncontrollable factors. |

| Motivate employees to improve their performance | The interest and commitment of employees can be retained via a system of feedback of actual results, which lets them know how well or badly they are performing. The identification of controllable reasons for departures from budget with managers responsible provides an incentive for improving future performance. Some argue that motivation can only come from within one’s self; encouragement and discouragement are the external stimuli |

Exam Focus Point

An exam question could well ask you to explain a number of these objectives in the context of a particular scenario such as a not-for-profit organisation.

BEHAVIOURAL IMPLICATIONS OF BUDGETING

Used correctly, a budgetary control system can motivate but it can also produce undesirable negative reactions.

The purpose of a budgetary control system is to assist management in planning and controlling the resources of their organisation by providing appropriate control information. The information will only be valuable, however, if it is interpreted correctly and used purposefully by managers and employees.

The correct use of control information therefore depends not only on the content of the information itself, but also on the behaviour of its recipients. This is because control in business is exercised by people. Their attitude to control information will colour their views on what they should do with it and a number of behavioural problems can arise.

- The managers who set the budget or standards are often not the managers who are then made responsible for achieving budget targets.

- The goals of the organisation as a whole, as expressed in a budget, may not coincide with the personal aspirations of individual managers.

- Control is applied at different stages by different people. A supervisor might get weekly control reports, and act on them; his superior might get monthly control reports, and decide to take different control action. Different managers can get in each others’ way, and resent the interference from others.

Motivation

Motivation is what makes people behave in the way that they do. It comes from individual attitudes, or group attitudes. Individuals will be motivated by personal desires and interests. These may be in line with the objectives of the organisation, and some people ‘live for their jobs’. Other individuals see their job as a chore, and their motivations will be unrelated to the objectives of the organisation they work for.

It is therefore vital that the goals of management and the employees harmonise with the goals of the organisation as a whole. This is known as goal congruence. Although obtaining goal congruence is essentially a behavioural problem, it is possible to design and run a budgetary control system which will go some way towards ensuring that goal congruence is achieved. Managers and employees must therefore be favourably disposed towards the budgetary control system so that it can operate efficiently.

The management accountant should therefore try to ensure that employees have positive attitudes towards setting budgets, implementing budgets (that is, putting the organisation’s plans into practice) and feedback of results (control information).

Poor attitudes when setting budgets

Poor attitudes or hostile behaviour towards the budgetary control system can begin at the planning stage. If managers are involved in preparing a budget the following may happen.

- Managers may complain that they are too busy to spend much time on budgeting.

- They may build ‘slack’ into their expenditure estimates.

- They may argue that formalising a budget plan on paper is too restricting and that managers should be allowed flexibility in the decisions they take.

- They may set budgets for their budget centre and not coordinate their own plans with those of other budget centres.

- They may base future plans on past results, instead of using the opportunity for formalised planning to look at alternative options and new ideas.

On the other hand, managers may not be involved in the budgeting process. Organisational goals may not be communicated to them and they might have their budget decided for them by senior management or administrative decision. It is hard for people to be motivated to achieve targets set by someone else.

Poor attitudes when putting plans into action

Poor attitudes can also arise when a budget is implemented.

- Managers might put in only just enough effort to achieve budget targets, without trying to beat targets.

- A formal budget might encourage rigidity and discourage flexibility.

- Short-term planning in a budget can draw attention away from the longer-term consequences of decisions.

- There might be minimal cooperation and communication between managers.

- Managers will often try to make sure that they spend up to their full budget allowance, and do not overspend, so that they will not be accused of having asked for too much spending allowance in the first place.

Poor attitudes and the use of control information

The attitude of managers towards the accounting control information they receive might reduce the information’s effectiveness.

- Management accounting control reports could well be seen as having a relatively low priority in the list of management tasks. Managers might take the view that they have more pressing jobs on hand than looking at routine control reports.

- Managers might resent control information; they may see it as part of a system of trying to find fault with their work. This resentment is likely to be particularly strong when budgets or standards are imposed on managers without allowing them to participate in the budget-setting process.

- If budgets are seen as pressure devices to push managers into doing better, control reports will be resented.

- Managers may not understand the information in the control reports, because they are unfamiliar with accounting terminology or principles.

- Managers might have a false sense of what their objectives should be. A production manager might consider it more important to maintain quality standards regardless of cost. He would then dismiss adverse expenditure variances as inevitable and unavoidable.

- If there are flaws in the system of recording actual costs, managers will dismiss control information as unreliable.

- Control information might be received weeks after the end of the period to which it relates, in which case managers might regard it as out-of-date and no longer useful.

- Managers might be held responsible for variances outside their control.

It is therefore obvious that accountants and senior management should try to implement systems that are acceptable to budget holders and which produce positive effects.

Pay as a motivator

Many researchers agree that pay can be an important motivator, when there is a formal link between higher pay (or other rewards, such as promotion) and achieving budget targets. Individuals are likely to work harder to achieve budget if they know that they will be rewarded for their successful efforts. There are, however, problems with using pay as an incentive.

- A serious problem that can arise is that formal reward and performance evaluation systems can encourage dysfunctional behaviour. Many investigations have noted the tendency of managers to pad their budgets either in anticipation of cuts by superiors or to make the subsequent variances more favourable. And there are numerous examples of managers making decisions in response to performance indices, even though the decisions are contrary to the wider purposes of the organisation.

- The targets must be challenging but fair, otherwise individuals will become dissatisfied. Pay can be a de-motivator as well as a motivator!

SETTING THE DIFFICULTY LEVEL OF A BUDGET

‘Aspirations’ budgets can be used as targets to motivate higher levels of performance but a budget for planning and decision making should be based on reasonable expectations.

Budgets can motivate managers to achieve a high level of performance. But how difficult should targets be? And how might people react to targets of differing degrees of difficulty in achievement?

- There is likely to be a de-motivating effect where an ideal standard of performance is set, because adverse efficiency variances will always be reported.

- A low standard of efficiency is also de-motivating, because there is no sense of achievement in attaining the required standards. If the budgeted level of attainment is too ‘loose’, targets will be achieved easily, and there will be no impetus for employees to try harder to do better than this.

- A budgeted level of attainment could be the same as the level that has been achieved in the past. Arguably, this level will be too low. It might encourage budgetary slack.

Academics have argued that each individual has a personal ‘aspiration level’. This is a level of performance in a task with which the individual is familiar, which the individual undertakes for himself to reach.

Individual aspirations might be much higher or much lower than the organisation’s aspirations, however. The solution might therefore be to have two budgets.

- A budget for planning and decision making based on reasonable expectations

- A budget for motivational purposes, with more difficult targets of performance

These two budgets might be called an ‘expectations budget‘ and an ‘aspirations budget‘ respectively.

BLANK

PARTICIPATION IN BUDGETING

A budget can be set from the top down (imposed budget) or from the bottom up

(participatory budget). Many writers refer to a third style, the negotiated budget.

Participation

It has been argued that participation in the budgeting process will improve motivation and so will improve the quality of budget decisions and the efforts of individuals to achieve their budget targets (although obviously this will depend on the personality of the individual, the nature of the task (narrowly defined or flexible) and the organisational culture).

There are basically two ways in which a budget can be set: from the top down (imposed budget) or from the bottom up (participatory budget).

Imposed style of budgeting (top-down budgeting)

In this approach to budgeting, top management prepare a budget with little or no input from operating personnel which is then imposed upon the employees who have to work to the budgeted figures.

The times when imposed budgets are effective are as follows.

- In newly-formed organisations

- In very small businesses

- During periods of economic hardship

- When operational managers lack budgeting skills

- When the organisation’s different units require precise coordination

There are, of course, advantages and disadvantages to this style of setting budgets.

Advantages

- Strategic plans are likely to be incorporated into planned activities

- They enhance the coordination between the plans and objectives of divisions

- They use senior management’s awareness of total resource availability

- They decrease the input from inexperienced or uninformed lower-level employees

- They decrease the period of time taken to draw up the budgets

Disadvantages

- Dissatisfaction, defensiveness and low morale amongst employees

- The feeling of team spirit may disappear

- The acceptance of organisational goals and objectives could be limited

- The feeling of the budget as a punitive device could arise

- Unachievable budgets for overseas divisions could result if consideration is not given to local operating and political environments

- Lower-level management initiative may be stifled

Participative style of budgeting (bottom-up budgeting)

In this approach to budgeting, budgets are developed by lower-level managers who then submit the budgets to their superiors. The budgets are based on the lower-level managers’ perceptions of what is achievable and the associated necessary resources.

Participative budgets are effective in the following circumstances.

- In well-established organisations

- In very large businesses

- During periods of economic affluence

- When operational managers have strong budgeting skills

- When the organisation’s different units act autonomously

The advantages of participative budgets are as follows.

- They are based on information from employees most familiar with their unit of operation

- Knowledge spread among several levels of management is pulled together

- Morale and motivation are improved

- They increase operational managers’ commitment to organisational objectives

- In general they are more realistic

- Co-ordination between units is improved

- Specific resource requirements are included

- Senior managers’ overview is mixed with operational level details

There are, on the other hand, a number of disadvantages of participative budgets.

- They often consume more time

- Changes implemented by senior management may cause dissatisfaction

- Budgets may be unachievable if managers’ are not qualified to participate

- They may cause managers to introduce budgetary slack

- They can support ’empire building’ by subordinates

- An earlier start to the budgeting process could be required

Negotiated style of budgeting

At the two extremes, budgets can be dictated from above or simply emerge from below but, in practice, different levels of management often agree budgets by a process of negotiation. In the imposed budget approach, operational managers will try to negotiate with senior managers the budget targets which they consider to be unreasonable or unrealistic. Likewise senior management usually review and revise budgets presented to them under a participative approach through a process of negotiation with lower level managers. Final budgets are therefore most likely to lie between what top management would really like and what junior managers believe is feasible. The budgeting process is hence a bargaining process and it is this bargaining which is of vital importance, determining whether the budget is an effective management tool or simply a clerical device.

BLANK

MUTUALLY EXCLUSIVE PROJECTS WITH UNEQUAL LIVES

All of the discounted cash flow examples that we have seen so far have involved a choice between projects with equal lives. However, if manager are deciding between projects with different time spans a direct comparison of the NPV generated by each project would not be valid.

For example if an organisation decides to invest in a project with a shorter life it may then have the opportunity to invest in a new project in the future sooner than if a longer term project is accepted. This should be taken into account in the analysis in order to be able to make direct comparisons between projects with unequal lives.

Annualised equivalents are used to enable a comparison made between the net present values of projects with different durations. However, this method cannot be used when inflation is a factor. Another method, the lowest common multiple method, is used instead.

Not all mutually exclusive investments need to be considered over the same level of time. It very much depends on what the organisation intends to do once the shorter-life project ends. If the organisation has to invest in similar assets again at that point, the projects should be compared over equal time periods. Investment in manufacturing equipment for a product that will be made for more years than the life of an asset is an example.

If the organisation does not have to invest in similar assets when the asset’s life ends, however, the approach we have described is not needed. If the investments are alternative advertising campaigns for a short-life product such as a commemorative item, the investments will be one-offs and so can be compared over different lives.

CHAPTER ROUNDUP

- Corporate objectives concern the firm as a whole. Unit objectives are specific to individual units , divisions or functions of an organisation.

- Primary corporate objectives are supported by secondary objectives, for example for product development or market share. In practice there may be a trade off between different objectives.

- The planning and control cycle has seven steps.

- Step 1. Identify objectives

- Step 2. Identify potential strategies

- Step 3. Evaluate strategies – SWOT analysis

- Step 4. Choose alternative courses of action

- Step 5. Implement the long-term plan

- Step 6. Measure actual results and compare with the plan

- Step 7. Respond to divergences from the plan

- Planning and control occurs at all levels of the performance hierarchy to different degrees.

- Budgetary control occurs at the lower levels of the performance hierarchy.

- Here are the objectives of a budgetary planning and control system.

- Ensure the achievement of the organisation’s objectives

- Compel planning

- Communicate ideas and plans

- Coordinate activities

- Provide a framework for responsibility accounting

- Establish a system of control

- Motivate employees to improve their performance

- Used correctly, a budgetary control system can motivate but it can also produce undesirable negative reactions.

- ‘Aspirations’ budgets can be used as targets to motivate higher levels of performance but a budget for planning and decision making should be based on reasonable expectations.

A budget can be set from the top down (imposed budget) or from the bottom up (participatory budget). Many writers refer to a third style, the negotiated budget.