WHAT ARE LIFE CYCLE COSTS?

Life cycle costing tracks and accumulates costs and revenues attributable to each product over the entire product life cycle.

A product’s life cycle costs are incurred from its design stage through development to market launch, production and sales, and finally to its eventual withdrawal from the market. The component elements of a product’s cost over its life cycle could therefore include the following.

- Research & development costs

- Design

- Testing

- Production process and equipment

- The cost of purchasing any technical data required

- Training costs (including initial operator training and skills updating)

- Production costs

- Distribution costs. Transportation and handling costs

- Marketing costs – Customer service

- Field maintenance

- Brand promotion

- Inventory costs (holding spare parts, warehousing and so on)

- Retirement and disposal costs. Costs occurring at the end of a product’s life

Life cycle costs can apply to services, customers and projects as well as to physical products.

Traditional cost accumulation systems are based on the financial accounting year and tend to dissect a product’s life cycle into a series of 12-month periods. This means that traditional management accounting systems do not accumulate costs over a product’s entire life cycle and do not therefore assess a product’s profitability over its entire life. Instead they do it on a periodic basis.

Life cycle costing, on the other hand, tracks and accumulates actual costs and revenues attributable to each product over the entire product life cycle. Hence the total profitability of any given product can be determined.

Life cycle costing is the accumulation of costs over a product’s entire life.

THE PRODUCT LIFE CYCLE

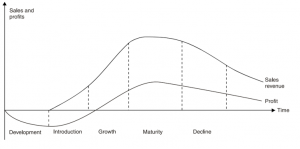

A product life cycle can be divided into five phases.

| • Development | • Maturity |

| • Introduction | • Decline |

- Growth

Every product goes through a life cycle.

- The product has a research and development stage where costs are incurred but no revenue is generated.

- Introduction. The product is introduced to the market. Without advertising or some similar means, the potential customers will be unaware of the product or service – more cost without revenue.

- Growth. The product gains a bigger market as demand builds up. Sales revenues increase and the product begins to make a profit.

- Maturity. Eventually, the growth in demand for the product will slow down and it will enter a period of relative maturity. It will continue to be profitable. The product may be modified or improved, as a means of sustaining its demand.

- Decline. At some stage, the market will have bought enough of the product and it will therefore reach ‘saturation point’. Demand will start to fall. Eventually it will become a loss-maker and this is the time when the organisation should decide to stop selling the product or service.

The level of sales and profits earned over a life cycle can be illustrated diagrammatically as follows.

The horizontal axis measures the duration of the life cycle, which can last from, say, 18 months to several hundred years. Children’s crazes or fad products have very short lives while some products, such as binoculars (invented in the eighteenth century) can last a very long time.

Problems with traditional cost accumulation systems

Traditional cost accumulation systems do not tend to relate research and development costs to the products that caused them. Instead they write off these costs on an annual basis against the revenue generated by existing products. This makes the existing products seem less profitable than they really are. If research and development costs are not related to the causal product the true profitability of that product cannot be assessed.

Traditional cost accumulation systems usually total all non-production costs and record them as a period expense.

THE IMPLICATIONS OF LIFE CYCLE COSTING

Life cycle costing has implications on pricing, performance management and decisionmaking.

With life cycle costing, non-production costs are traced to individual products over complete life cycles.

- The total of these costs for each individual product can therefore be reported and compared with revenues generated in the future.

- The visibility of such costs is increased.

- Individual product profitability can be better understood by attributing all costs to products.

- As a consequence, more accurate feedback information is available on the organisation’s success or failure in developing new products. In today’s competitive environment, where the ability to produce new or updated versions of products is paramount to the survival of an organisation, this information is vital.

The importance of the early stages of the life cycle

It is reported that some organisations operating within an advanced manufacturing technology environment find that approximately 90% of a product’s life cycle cost is determined by decisions made early within the cycle – at the design stage. Life cycle costing is therefore particularly suited to such organisations and products, monitoring spending and commitments to spend during the early stages of a product’s life cycle.

In order to compete effectively in today’s market, organisations need to redesign continually their products with the result that product life cycles have become much shorter. The planning, design and development stages of a product’s cycle are therefore critical to an organisation’s cost management process. Cost reduction at this stage of a product’s life cycle, rather than during the production process, is one of the most important ways of reducing product cost.

Maximising the return over the product life cycle

Design costs out of products

Between 70% to 90% of a product’s life cycle costs are determined by decisions made early in the life cycle, at the design or development stage. Careful design of the product and manufacturing and other processes will keep cost to a minimum over the life cycle.

Minimise the time to market

This is the time from the conception of the product to its launch. More products come onto the market nowadays and development times have been reduced over the years. Competitors watch each other very carefully to determine what types of product their rivals are developing. If an organisation is launching a new product it is vital to get it to the market place as soon as possible. This will give the product as long a period as possible without a rival in the market place and should mean increased market share in the long run. Furthermore, the life span may not proportionally lengthen if the product’s launch is delayed and so sales may be permanently lost. It is not unusual for the product’s overall profitability to fall by 25% if the launch is delayed by six months. This means that it is usually worthwhile incurring extra costs to keep the launch on schedule or even to speed up the launch.

Minimise breakeven time (BET)

A short BET is very important in keeping an organisation liquid. The sooner the product is launched the quicker the research and development costs will be repaid, providing the organisation with funds to develop further products.

Maximise the length of the life span

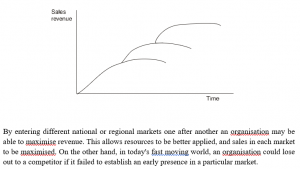

Product life cycles are not predetermined; they are set by the actions of management and competitors. Once developed, some products lend themselves to a number of different uses; this is especially true of materials, such as plastic, PVC, nylon and other synthetic materials. The life cycle of the material is then a series of individual product curves nesting on top of each other as shown below.

By entering different national or regional markets one after another an organisation may be able to maximise revenue. This allows resources to be better applied, and sales in each market to be maximised. On the other hand, in today’s fast moving world, an organisation could lose out to a competitor if it failed to establish an early presence in a particular market.

Minimise product proliferation

If products are updated or superseded too quickly, the life cycle is cut short and the product may just cover its R and D costs before its successor is launched.

Manage the product’s cashflows

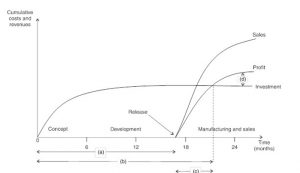

Hewlett-Packard developed a return map to manage the lifecycle of their products. Here is an example.

Key time periods are measured by the map:

- Time to market

- Breakeven time

- Breakeven time after product launch

- Return factor (the excess of profit over the investment)

Changes to planned time periods can be incorporated into the map (for example, if the development plan takes longer than expected) and the resulting changes to the return factor at set points after release highlighted.

Service and project life cycles

A service organisation will have services that have life cycles. The only difference is that the R & D stages will not exist in the same way and will not have the same impact on subsequent costs. The different processes that go to form the complete service are important, however, and consideration should be given in advance as to how to carry them out and arrange them so as to minimise cost.

Products that take years to produce or come to fruition are usually called projects, and discounted cash flow calculations are invariably used to cost them over their life cycle in advance. The projects need to be monitored very carefully over their life to make sure that they remain on schedule and that cost overruns are not being incurred.

Customer life cycles

Customers also have life cycles, and an organisation will wish to maximise the return from a customer over their life cycle. The aim is to extend the life cycle of a particular customer or decrease the ‘churn’ rate, as the Americans say. This means encouraging customer loyalty. For example, Europe some large chain retail outlets issue loyalty cards that offer discounts to loyal customers who return to the shop and spend a certain amount with the organisation. As existing customers tend to be more profitable than new ones they should be retained wherever possible.

Customers become more profitable over their life cycle. The profit can go on increasing for a period of between approximately four and 20 years. For example, if you open a bank account, take out insurance or invest in a pension, the company involved has to set up the account, run checks and so on. The initial cost is high and the company will be keen to retain your business so that it can recoup this cost. Once customers get used to their supplier they tend to use them more frequently, and so there is a double benefit in holding on to customers. For example, you may use the bank to purchase shares on your behalf, or you may take out a second insurance policy with the same company.

The projected cash flows over the full lives of customers or customer segments can be analysed to highlight the worth of customers and the importance of customer retention. It may take a year or more to recoup the initial costs of winning a customer, and this could be referred to as the payback period of the investment in the customer.

CHAPTER ROUNDUP

- Life cycle costing tracks and accumulates costs and revenues attributable to each product over the entire product life cycle.

- A product life cycle can be divided into five phases.

− Development

− Introduction

− Growth

− Maturity

− Decline

- Life cycle costing has implications on pricing, performance management and decisionmaking.