METHODS OF REMUNERATION

Fixing Wage Rates

Wage rates may be fixed by individual agreement between employer and employee, or more commonly by collective bargaining between trade unions and employers’ associations.

An employer may pay wages on an hourly basis, per piece, or may adopt one of the various bonus methods of payment, but the general principle of a wages policy is to obtain the maximum production per RWF of wages paid while maintaining an acceptable quality of production, within the limits of “social justice” (i.e. employees should receive a “fair day’s wages”).

In deciding on the method of remuneration to use, attention must be paid to the following factors:

- The relative importance of quantity and quality, and the cost of spoilage.

- The degree of specialisation and standardisation of the product.

- The degree to which automatic or semi-automatic machines are used.

Main Methods

Workers may be paid by time of attendance or by results. The latter method provides an incentive to increase production. “Payment by results” covers:

- Piece Rates:

These may be:

− Straight piece rates

− Piece rates with guaranteed minimum − Differential piece rates.

- Bonus Schemes:

These can be any of the following:

− Bonus schemes for direct workers individually

− Bonus schemes for direct workers in groups

− Bonus schemes for indirect workers − Bonus schemes for staff.

Performance-Related Pay

- Indirect Monetary Incentives:

These may take the form of:

− Co-partnership schemes

− Profit-sharing schemes − Allowances and expenses of various kinds.

- Non-Monetary Incentives:

These are further inducements to increase output. They include security of employment, prospects of promotion and the satisfaction that a job gives to an employee (i.e. craft work as opposed to repetitive production).

TIME RATES

At Ordinary Levels

This system is the most common method of wage payment in Britain. It is a system of paying workers for the time worked rather than for work produced. It may be in the form of an hourly rate, or shift or weekly rate for an agreed number of hours. We must examine the circumstances in which it is most favoured, and its advantages and disadvantages.

Where the System Can be Favoured

- Where the work done is very difficult to measure, e.g. when a service is rendered – nurses, policemen, probation officers, lift attendants, teachers – or when the work cannot be standardised, e.g. the majority of clerical operators or administrative work.

- When workers are learning, e.g. apprentices.

- Where the speed of the machine, operation, or process governs the speed at which the operator can work, e.g. assembly lines, chemical plants, and process industries such as bottle or paper making.

- When quality of production is of prime importance and would be endangered by encouraging an operator to work faster.

- When safety is likely to be endangered if the operation is speeded up, e.g. lorry driver.

- When it is found that good employer/employee relations exist and a satisfactory output is being achieved. The introduction of an incentive scheme may disrupt the good employer/employee relations, causing discontent and possibly lower production.

- When work is so unstandardised that the expense and difficulty involved in measuring the work done, etc. would be so great as to outweigh any advantages accruing from an incentive scheme.

Advantages

- The system is simple to understand and simple to operate, saving on clerical labour in number and quality of staff.

- Wages are stable, an advantage rated very highly by many workers.

Disadvantages

- The system provides no direct incentive to the worker to increase output or to produce better quality work.

- It tends towards higher production costs because the workers tend to work at an accepted minimum rate.

- It requires close supervision, and in times of full employment the worker’s output is greatly dependent on his goodwill and conscientious attitude, since there is no fear of dismissal.

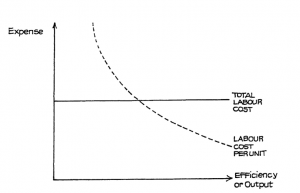

Effect of Variations in Output

Any gain or loss arising from variations in the operators’ efficiency will be borne by the employer. Thus, if the daily wage of each of four operators is RWF40:

If A produces 20 units his labour cost per unit is RWF2, i.e. RWF40 divided by 20 units.

If B produces 40 units his labour cost per unit is RWF1, i.e. RWF40 divided by 40 units.

If C produces 80 units his labour cost per unit is RWF0.50, i.e. RWF40 divided by 80 units.

If D produces 100 units his labour cost per unit is RWF0.40, i.e. RWF40 divided by 100 units.

Clearly, labour cost per unit falls with increased production. This is illustrated in Figure 20.

High Wage Plan

Significant Points

- An appreciably higher than average wage is paid compared with other factories in the area.

- A higher standard of output, both in quality and quantity, is set.

- As a vacancy attracts a larger number of applicants, the employer can secure the services of better workers, who will be willing to maintain the higher standard in order to retain their jobs and the higher wages.

Advantages

- It is simple to understand and operate.

- Wages are stable.

- It overcomes the lack of incentive of ordinary time rates.

- Output increases, and as a result, the cost per unit falls, compensating the employer for the increase in wages.

Disadvantages

- As with ordinary time rates, this system still does not provide incentive for exceptional effort and ability.

- It requires close supervision.

Graduated Time Rates

These are time rates adjusted for particular reasons, e.g. changes in the cost of living, additional rates for merit, loyalty, etc.

INCENTIVE SCHEMES

General Principles

There are some general principles which should apply to all incentive schemes:

- The reward should be as nearly related to effort as possible, both in amount and in time of payment.

- The scheme should be fair to both employer and employee.

- There should be mutual agreement to ensure that the basis of the scheme is fully understood, covers all reasonable points, and is not capable of being misinterpreted.

- The scheme should be strong and positive; it should have clearly defined, worthwhile and attainable objectives.

- There should be no limits placed upon the amount of additional earnings.

- The incentives should not be affected by matters outside the employees’ control.

- The incentive should be reasonably permanent, not merely a device to be used by the employer when business is good and dropped when it is not.

- The rates for payment by results should be fixed only after the job has been properly assessed.

- Piece rates or time allowances, once fixed, should remain, unless conditions or methods change.

- The standard of performance set must be reasonably attainable by the average employee and it should be possible to demonstrate that this is so.

- The scheme should be simple, capable of being understood by the workers so that they can make their own calculations, and easy to operate with the minimum of clerical work.

- A properly prepared incentive scheme should assist supervision and help to reduce the cost of it. (n) The scheme should be in conformity with any national, local or trade agreement.

Reasons for Having an Incentive Scheme

Before we discuss various incentive schemes, it would be useful if we considered the difference such a scheme of remuneration might make to certain firms.

Firms with high fixed overheads will want to increase output as much as possible, because by increasing output they can spread the fixed overheads over a larger number of units, thus reducing the fixed cost per unit – assuming, as we have already seen, that absorption costing is in operation.

Under some incentive schemes the labour cost per unit will rise, but by increasing the output, the total cost per unit will fall (again employing absorption costing).

PIECE-RATES

Advantages of Piece Rates

- Time wasted by employees is not paid for, although much depends on the cause of the idle time and on the agreement in force in the particular industry.

- Each worker is paid on his merits, and thus individual effort is encouraged.

- The increase in production through the workers being induced to work faster causes a decrease in the fixed expenses chargeable to each unit (in an absorption costing context).

- The employer knows in advance the exact direct labour cost of each job; this information is invaluable when tendering for work.

- The workers tend to be more careful with tools and equipment when they know that any mishap to these will reduce their own earning powers.

Disadvantages

- Difficulty may be encountered in fixing an equitable rate

- Slow workers may feel discontented as they will receive a lower wage than the faster worker. Trade unions are often opposed to piece work on this ground and also on the ground that the greater speed of production due to piece work may reduce employment opportunities in the long run.

- Excessive waste of material may be caused through the workers attempting to work quickly. Scrapped work will not be paid for, but the employer will lose to the extent of the overheads involved and the cost of the material spoilt, particularly if any of the unsatisfactory work has been allowed to continue in production and has passed through subsequent operations. It would be advantageous to introduce a penalty for spoiled work but this would be very difficult.

- Unless some differential or bonus system is introduced, there is no extra reward for exceptional effort, e.g. a worker is paid the same per unit for producing one unit or 50 units. Conversely, no fine is levied for slow production and although only a small wage is earned, the overhead expenses per unit will increase.

- Payment may be irregular, because of numerous factors, e.g. sickness, breakdown of machinery, shortage of raw materials, and bad weather.

In many industries, however, there are now agreements providing for the payment of a guaranteed minimum week when causes outside the control of the workers operate to disturb or prevent normal production.

- If the proportion of overhead to labour cost is very low, then there is little advantage to be gained.

- It is stated that over-production may result from speedy work, although it should be possible, with an efficient planning and production control (or progress) department, to ensure that only the required amounts of any commodity are produced.

- The risk of accidents may be increased.

- Piece rates may encourage individuals to work purely for themselves and there may be a lack of co-operation in the department.

- There may be a tendency towards absenteeism and bad time-keeping, especially when workers feel they have earned “enough”.

DIFFERENTIAL PIECE-RATE SYSTEMS

The principle behind differential piece-rate systems is to introduce an additional incentive, at the point when most workers feel it is not worthwhile putting any more extra effort into their work – in other words, to encourage them to put in that extra effort.

For example, let us consider lifting potatoes. If there are 12 potato plants in each row, it will not be difficult to dig up one row in one day, but if we are only being paid RWF2 per row it will not give us much of a day’s wage. If we dig up 20 rows this will give us a wage of RWF40, 21 rows a wage of RWF42 and so on. You will probably agree that to dig another row after the twenty-first is going to involve considerable effort – much more effort than the first row. Under a straight piece-work system, we are still paid RWF2 for the first or the twenty-first row.

Taylor realised that the straight piece-work system gave no additional incentive to workers for outstanding effort. He introduced the differential piece-work system, under which a worker receives an additional bonus after he reaches a certain level of output. Thus, in our example of potato lifting, Taylor might have introduced a rate of RWF3 per row once the work has reached 25 rows. Once the figure of 25 has been reached, the RWF3 per row will be paid for all the rows dug (not just for those after 25), thus giving a very strong incentive to the worker to reach and pass the 25 figure.

Differential piece-rate systems are suitable when there are relatively high fixed costs in comparison with direct wages; the aim is continuous maximum production.

PREMIUM BONUS SCHEMES

The main systems using the premium bonus principle are Halsey or Halsey-Weir and Rowan systems. These are important and most examination questions on incentive schemes will he based on them

In premium bonus systems a time allowance and not a piece rate is made for a job. The bonus arising from greater production is shared between employer and employee. Compare this with straight piece work where all the gains or losses arising from labour efficiency or inefficiency are borne by the employee, while the reverse is true with guaranteed time rates, when all gains or losses arising from labour efficiency are borne by the employer

Basic Features

The following points apply to premium bonus schemes:

- Basic time rate is guaranteed.

- The hourly rate of employees increases, but at a lower rate than production.

- A low task is set, e.g. 70% of standard. The result is that employees begin earning bonus at a relatively low level of output, encouraging them to increase efforts.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages

- (c) above is probably the most important – it encourages workers and even learners to increase efforts.

- There is a guaranteed basic wage.

- The system is reasonably simple to understand.

- The employer benefits by sharing in the saving of time, which may encourage him to install time-saving machinery and improve methods.

- The system is suitable where it is impossible to measure production standards with a high degree of accuracy.

- The system can be operated after very little time study and investigation. Obviously, the more elaborate the preparation the more accurate will be the rate setting, but this will increase the overhead costs. Being able to operate the system almost at once can be a very important advantage.

Disadvantages

- Employees often object to sharing the savings in time and it is difficult to explain or to justify the principle to the workers.

- Incentive is not nearly as strong as for straight piece work.

- Direct labour costs increase at low levels of output when compared with a straight piece-work system and even when compared with a guaranteed day-wage system.

Halsey System, or Halsey-Weir System

This is a premium bonus scheme with a time-rate guarantee. Standard time is allowed for the job, and if this time or longer is taken, time rate is paid. If less time is taken the worker is paid a fixed percentage of the saving in time. In practice the bonus percentage varies between 30% and 70% of time saved; the usual proportion is 50%.

Rowan System

This is also a premium bonus scheme. A standard time is allowed for a job and a bonus paid for the time saved. The bonus is paid as a percentage addition to the time rate, equal to the percentage of time saved to standard time.

There are two methods of calculation:

|

(a) |

Time wages + (% Hours saved × Time wages). |

| (b) Time taken + Time taken × Time saved × Time rate per hour

Time allowed |

Assume: Time rate RWF4 per hour

Time allowed 50 hours

Time taken 40 hours

Earnings would be RWF160 + (20% × RWF160) = RWF192.

You will notice that, under the Rowan system, the worker is paid more than under the Halsey system at levels of production just over standard; but the Halsey system gives the worker a much higher incentive at high levels of efficiency.

GROUP BONUS SCHEMES

General Principles

Incentive bonus schemes can be applied to the group as well as to individuals. The bonus is calculated for the group and shared among them on an agreed basis.

Use

Group bonus schemes are usually introduced where particular circumstances apply:

- Where there is a desire to encourage an “esprit de corps” in the factory.

- Where it is impossible to measure an individual’s output, as in many automated processes. The output is dependent on the group.

- Where individual bonus schemes are causing jealousy among workers and possibly a reduction in co-operative effort.

- Advantages

- The great advantage is that the group bonus scheme promotes team work. The bonus is paid to all workers, i.e. not only direct workers but foremen, inspectors, internal transport workers, tool-men, etc.

- It may encourage poorer workers to work harder, following the lead of better workers. Poorer workers may feel that they cannot let their team-mates down and may therefore put extra effort into their work

- Group bonus schemes are usually simple and fairly cheap to operate compared with individual schemes.

- Mutual supervision is often exercised by the group members.

Disadvantages

- Many employers contend that total output tends to fall because good workers have not the same incentive to work as efficiently.

- The incentive may be lessened as wages tend to be more constant than in individual schemes.

Bonus Schemes for Indirect Workers

These usually take the form of, say, a proportion of the average bonus of a related group of direct workmen, or of a shop.

Staff Incentive Schemes

These are not common but may take many forms.

A bonus for a foreman may be related to the output of his department, or the total hours saved in his department.

The grading of clerical staff may persuade people to work to attain a higher grade and thus increase earnings. In some cases work measurement may be made the basis (see later). This applies particularly to machine operators such as typists and data processing input operators.

PERFORMANCE-RELATED PAY

In recent years many organisations have introduced remuneration systems in which the wage and salary levels are based upon the performance of individual employees. These systems are aimed at rewarding employees according to their performance, ensuring that those employees who perform the best receive the highest rewards. Incentives are also built into the remuneration system that motivate employees to improve their performance at work. Examples of performance-related pay are:

- Sales personnel who are paid a commission on sales.

- Branch managers whose pay is based upon the profits earned by each branch.

PROFIT SHARING AND CO-PARTNERSHIP

Profit sharing and co-partnership are not synonymous; you should be able to define each one.

Definitions

- Profit Sharing

The definition of profit sharing, as agreed at an international congress in 1889, is that “an employer agrees with his employees that they shall receive in partial remuneration of their labour, and in addition to their wages, a share, fixed beforehand, in the profits realised by the undertaking”.

Be careful to note that the share in the profits is fixed beforehand and is not a bonus granted at the discretion of the employer, although the agreed formula will usually define the limits which will permit a profit share.

- Co-Partnership

Co-partnership gives the workers an opportunity to share in the profits, capital and control of the undertaking.

Thus, the worker will participate in the profits of the firm in addition to standard wages. He should be able to accumulate his share of profits in the capital of the company and, if these are in the form of shares with voting rights, he will automatically share in the control of the undertaking. A share in the control of the undertaking may also be secured by forming a co-partnership committee of workers, which will have some influence in the management of the firm.

Methods

There is a great variety of methods used in schemes for profit sharing and co-partnership. Circumstances differ among firms and consideration will be given to the following points:

- Capital employed and the division of profit between capital and labour.

- Labour employed and to what extent labour influences output and cost of production

Once the amount of profit to be divided among the workers has been decided upon we have a problem, namely how is this money to be divided among the workers? A straight percentage of wages would not compensate for loyalty, long service, etc. On the other hand, a person employed for a few months has not contributed fully to the profits.

This brings us to the question of qualification for participation in the scheme, e.g. at age 21 or after one or two years’ service are possible qualifications. It is important that the qualifications are decided before the scheme begins – and agreed with those who hope to participate in it.

Advantages and Disadvantages

- Advantages

- The most important advantage is that the scheme can be designed to reduce labour turnover, e.g. double bonus may be paid after five years’ service or there may be a system of increasing bonuses after every four years’ service.

- It does help to build up a team spirit. The status of the worker is raised, particularly with co-partnership, when workers may have a little influence in management decisions through their share voting rights.

- It is said to stimulate interest in the work and increase efficiency; for instance, the employee may feel it is worthwhile making more suggestions.

- It is said to increase productivity.

- Disadvantages

- There is considerable difficulty in deciding on a basis for apportioning the profits as indicated above.

- Profits fluctuate; therefore bonuses will fluctuate and may sometimes be zero.

- Workers in fact have little say in management policy. Although policy decisions may be best for the firm in the long term, they may not be for immediate profits.

- Trade unions have been against such schemes, arguing that they weaken the trade unions, and that share ownership is “an extension of the capitalist society”.

- The poor workers share equally with good workers.

- The scheme provides no direct incentive because rewards are too long deferred,

i.e. paid once, or possibly twice, per annum.

- Employees may not trust the figures given by management.

- The amount of profit is not controlled solely by the workers, efforts, and this makes them suspicious of the scheme. For example, suppose the workers work at the same level of efficiency in two successive years, but because the buying department makes a highly profitable purchase, the first-year profits and bonuses are high. In the second year there could be a trade depression and profits and bonuses will probably be non-existent.

- Workers share in the profits of good years but do not suffer the losses of bad years.

NON-MONETARY INCENTIVES

Purpose

Financial incentives aim mainly at immediate results, while the object of non-monetary incentives is, in general, to build up output over a long-term period, by the following methods:

- Encouraging loyalty in the firm and reducing labour turnover.

- Improving the employees’ health, thus reducing absences through illness and increasing efficiency because the workforce is physically fitter.

- Building up a happy and contented staff, thus reducing absenteeism and increasing output through more willing co-operation.

- Making prospects with the firm attractive so that it can select the best workers when a vacancy arises.

- Building up good industrial relations, thereby reducing strikes.

- Giving the worker a sense of purpose and a feeling of security through the interest shown by management in providing the various amenities.

Various Aspects

It is impossible to list all non-monetary incentives but you should consider the following:

- Health:

− Medical unit in the factory staffed by trained nursing and first-aid staff and possibly a doctor.

− Safety officer. − Provision for private medical treatment.

- Canteen: − Subsidised meals, ensuring that workers have at least one substantial meal per day.

- Social: − Sport as well as dancing and social gatherings.

- Education:

− Day-release facilities or provision for full-time sandwich courses.

− Prizes and/or increments in salary for examination successes.

− Training in all branches of the firm so that employees have the experience when there is a possibility of internal promotion.

MEASUREMENT OF THE EFFICIENCY OF LABOUR

Efficiency Ratio

The efficiency (productivity) ratio is defined as:

Standard hours of output × 100% Actual hours to produce output

Output per Man/Hour

This is an alternative method of measuring overall efficiency, where total output is divided by the number of hours taken to produce it.

The method of calculating “man-hours” may or may not include both direct and indirect workers. It is probably better, from the point of view of controlling labour costs, to include both.

Trends in this statistic need careful interpretation. For instance, if further mechanisation is introduced, output per man/hour should increase. (The efficiency ratio would automatically take account of such changes because the standard hours allowance would be adjusted on any change in methods.)

An alternative to “output per man/hour” would be “output per RWF100 of labour cost”. This takes account of wages increases: if a pay rise is awarded, output must increase if the “output per RWF100” statistic is not to decrease.

Ratio of Direct to Indirect Labour

Provided the degree of mechanisation does not change, management should control the proportion of indirect labour. If the ratio shows that indirect labour forms an increasing proportion, this points to administrative inefficiency. On the other hand, too low a proportion of indirect labour may mean that direct workers are not receiving the back-up services they need.

Care needs to be taken in interpreting this measure, however, as clearly the proportion of direct workers will fall with increasing mechanisation. There is thus no “ideal” ratio which can be quoted.

LABOUR TURNOVER

We mentioned in the previous study unit that the various incentive schemes can help to reduce labour turnover. Now we will study this topic in more detail.

Measuring Labour Turnover

The most common measure of labour turnover is:

Number of leavers replaced × 100%

Average workforce

Thus, if a reduction in the workforce were planned, e.g. by offering early retirement, the people retiring early would not enter into the turnover statistics. In measuring labour turnover, management is concerned to control the cost of having to replace those employees who leave.

Cost of Labour Turnover

The cost of labour turnover can be high. It includes the following:

- Personnel Department

Under this heading come all the costs associated with recruitment: advertising, interviewing, interviewees’ expenses, etc.

- Training New Recruits and Losses Resulting

Every new recruit must have some training. Training costs money, i.e. the time of another operator who has to show the new beginners how to do the job; or the time of a supervisor or training school.

Even after training, the beginner will be unable for some time to do a full day’s work equivalent to that of a skilled operator with years of experience. The result is that the machines used by the new recruit are underemployed, causing further loss.

The new recruit is also likely to cause more scrap and possibly break tools and equipment more readily than a skilled operator. He or she is also more liable to accidents, causing further loss.

Reasons for Turnover

A certain amount of labour turnover is inevitable – employees retire or die, thus giving younger staff opportunities for promotion. However, as has been pointed out, labour turnover is costly and so should be controlled. Every effort should be made to find out why workers leave and, where defects are found, to put them right.

Where labour turnover is high and workers are being regularly lost to other firms in the same locality, the following factors require careful consideration:

- Methods of wage remuneration, e.g. is skill being adequately rewarded? Does average remuneration compare well with other local firms? Can workers reach an adequate rate of earnings without a high proportion of overtime working?

- Have the employees confidence in the future long-term prospects of employment within the organisation?

- Is there any antagonism on the part of the employees, owing to inefficient management?

- Are there sufficient general incentives to encourage employees to stay within the organisation, e.g. long service awards, pensions, canteen facilities, joint consultation, sports and recreational facilities, etc?

Suggested Remedies

- Personnel Department

If recruitment procedures are good, labour turnover will be reduced because the right people will be given the right jobs.

The personnel department can also help reduce labour turnover by developing and maintaining good employee/employer relations. Joint consultation may be developed. Clearly wage rates will be an important issue, as will opportunities for training and promotion.

- General Welfare

Good employee/employer relations may be developed by the personnel department but certain services will also go a long way towards maintaining such relationships and improving morale. The most important of these include the provision of sports facilities, e.g. sports field, tennis court, , etc; canteen facilities with, possibly, subsidised meals; adequate first-aid facilities with possibly a medical centre run by a doctor (depending on the size of the firm); pension scheme – a very powerful factor in reducing labour turnover among employees.. Part of the expense of providing these facilities must be set against the cost of labour turnover, although some of these services will also tend to reduce absenteeism and sickness.

RECORDING LABOUR COSTS

The calculation of wages and payroll normally requires two sets of documentation in respect of each employee, i.e. a time record and a work summary record. By evaluating each record separately and then comparing the respective payable hours, we can be sure that a full analysis has been made for cost purposes.

Time Recording

The recording of gate times, i.e. the arrival of each employee at the works in the morning and his or her departure in the evening, is very important. A number of methods are in use, depending on the number of employees involved, and you must know the outline of these methods. If you work in a large factory with the latest machinery you may feel that some of these methods are old fashioned, but in cost accounting it is important to bear in mind that circumstances in different concerns vary considerably and what may be old fashioned and cumbersome in a large works may be the most convenient way of dealing with a small factory of 20 or 30 employees. You must remember that the costing methods to be used in any business must be the most suitable for that business, and not necessarily those which have proved successful elsewhere.

More attention is being paid nowadays to effective clocking systems. The sellers of the many types of clock claim, quite justifiably, that an installation which includes a time clock, other clocks and a “hooter”, all synchronised, more than pays for itself in a short time by reason of the extra production resulting from more prompt starts, precisely-timed tea breaks, etc. These systems are usually obtainable on a rental basis, which includes full maintenance, at a reasonable cost.

Try to inspect some different types of machine and system; make sure that you are fully aware of the method adopted by your own employer.

Time Recording Methods

Time Book

Here, employees on arrival write their names in a book which is ruled off at the time for starting, late arrivals signing below the line, or alternatively the names are placed in alphabetical order and each employee enters his or her time of arrival.

Check or Disc Method

Here, numbered metal discs are hung up outside the office. On arrival, each employee removes a disc bearing his or her own number and places it, either in a receptacle, or on another board, also numbered.

Note that the time book and disc methods record only the fact of early arrival or lateness and not the extent of this, but they both have the advantage of being simple to operate.

INDIRECT LABOUR

In all works, some staff will be employed on servicing work, e.g. plant maintenance. Where an employee is continuously engaged on the same type of service or indirect labour, a record of his or her work may not be required since the total wages may be charged to the one expense account. Where an employee undertakes various kinds of indirect work, however, it may be necessary to keep some record of the manner in which he or she spends his or her time, so that the labour costs may be allocated to the correct accounts in the cost ledger. A time-sheet similar to that shown in Figure 27 may be used.

(From Study Unit 2 you will recall that direct labour is where the employee’s efforts are applied directly to a product or saleable service which can be identified separately in a product cost.)

| Name:

Clock No.: |

Rate per Hour | ||||||||

| Nature of Work | Hours |

RWF |

|

||||||

| Th. | Fri. | Sat. | Mon. | Tues. | Wed. | Total | |||

| Machinery Repairs | |||||||||

| Dept A | |||||||||

| ” B | |||||||||

| ” C | |||||||||

| Machine Cleaning | |||||||||

| ” Oiling | |||||||||

|

|

Sig. …………………………………………………. | ||||||||

Figure 27: Indirect Labour Record

Examples of Direct and Indirect Labour

| Direct | Indirect |

| P | |

| P | |

| P | |

| P | |

| P | |

| P |

Wages of Support Staff

Bonuses

Basic Pay of Indirect Workers

Basic Pay of Direct Workers

Cost of Idle Time

Overtime at Request of Customer Order

TREATMENT OF OVERTIME

It is not within the scope of a cost accountant’s duties to decide whether or not overtime working should be authorised, but he or she must record the cost of such working, analyse the cause and report the facts to management. Clearly, when a department has had idle time during normal working hours and has worked overtime, this situation should be referred to higher management.

There should be a separate column on the pay sheets for overtime so that it is possible to obtain the total overtime cost quickly.

For employees who are required to work “unsocial hours” it is now common practice to make shift premium payments as an additional incentive. These are a particular feature of operations that have to be run on a 24-hour, 365 days of the year basis and, eventually, they tend to lose their free incentive advantage, once the employee has become used to receiving them on a regular basis.

The underlying principle for charging overtime is: charge the cost to the cost unit causing the expense. This may be illustrated as follows:

Job Cost

Charge to individual jobs if customer wishes delivery date to be brought forward and overtime has to be worked to do so.

General Overhead

This category of overhead account is charged with overtime if general pressure of business has caused occasional overtime working. It would be unfair to make an extra charge to those jobs which just happened to be done in the evening.

Direct Labour Cost

On the other hand, if overtime is worked regularly and consistently because of a shortage of direct workers, it is really part of the normal direct labour cost and should be treated accordingly. An average hourly rate would be calculated based on the number of hours at standard rate and the number of hours at premium rates, and all jobs would be charged with labour at this average rate.

Departmental Overhead

- If inefficiency within a particular department has caused overtime then that departmental overhead account should be charged with the cost.

- If overtime has been worked in Department B because Department A was inefficient, the cost of overtime in Department B should be charged to the departmental overhead of Department A.

SUMMARY

The information given in this study unit covers a broad spectrum of the recording systems used. It must be emphasised that each industry has its own problems in recording both attendance times and work-on-the-job times and that the solutions adopted are likely to be unique. Great care needs to be taken to ensure that enough data is collected to meet central requirements without making the procedure so onerous that it becomes inefficient.