Introduction to Advanced Performance Management (APM)

APM will require you to assess different approaches to performance management from a variety of perspectives. This will require you to know what the approaches are and, more importantly, you should be able to compare one with another.

This exam will focus on performance management systems. These are the systems within the organisation by which the performance of the organisation is measured, controlled and improved.

2 Common knowledge

APM builds on knowledge gained in Performance Management (PM). It also includes knowledge contained in the Strategic Business Leader (SBL) exam but it is not a problem if you are yet to study for this exam.

PM tested your knowledge and application of core management accounting techniques. APM develops key aspects introduced at PM level with a greater focus on linking the syllabus topics together and evaluation of the key topics and techniques. Therefore, you should not expect to be retested in a PM style but need to be aware that all PM knowledge is assumed to be known.

In the same way, APM contains knowledge included in the SBL exam but it is important to draw a distinction between the two exams. You need to approach the common topics from an APM perspective, i.e. how do they influence performance management and measurement.

For example, in terms of strategy planning and choice, a SBL question might look at evaluating a strategic decision. However,

- The focus in APM would look at whether the company has a suitable mission and some key strategic objectives, then at what the critical success factors (CSFs) are for these objectives and then at what key performance indicators (KPIs) are being used.

- APM very much focuses on that hierarchy and questions revolve around whether the CSFs/KPIs are appropriate for the objectives and why. If they aren’t, then why not and what could the organisation do better.

- APM thus looks more at what performance management systems are needed and what performance measures are most appropriate.

1 includes the following topics from SBL:

- Strategy and strategic planning

- CSFs and KPIs

- Benchmarking

- SWOT

- BCG matrix

- Porter’s generic strategies.

3 Introduction to 1

This sets the scene to Part A of the syllabus, ‘strategic planning and control’. It introduces the process of strategic planning and control and evaluates how models such as SWOT, Boston Consulting Group and Porter’s generic strategies may assist in the performance management process and reviews the methods for benchmarking performance.

It also explores the changing role of the management accountant and explores the role of the management accountant in integrated reporting (syllabus section C).

4 Introduction to planning and control

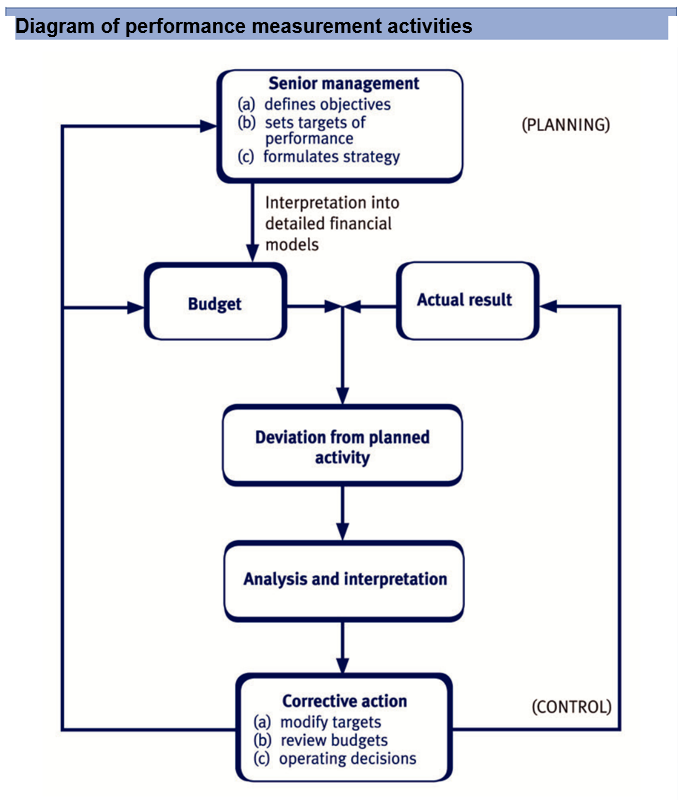

4.1 Definitions

Planning and control are fundamental aspects of performance management.

Strategic planning is concerned with:

- where an organisation wants to be (usually expressed in terms of its objectives) and

- how it will get there (strategies).

Control is concerned with monitoring the achievement of objectives and suggesting corrective action.

4.2 Planning and control at different levels within an organisation

Planning and control takes place at different levels within an organisation. The performance hierarchy operates in the following order:

- Mission

- Strategic (corporate) plans and objectives

- Tactical plans and objectives

- Operational plans and targets.

4.3 Mission

A mission statement outlines the broad direction that an organisation will follow and summarises the reasons and values that underlie that organisation.

A mission should be:

- succinct

- memorable

- enduring, i.e. the statement should not change unless the entity’s mission changes

- a guide for employees to work towards the accomplishment of the mission

- addressed to a number of stakeholder groups, for example shareholders, employees and customers.

Illustration 1 – Mission statement examples

American Express – famous for their great customer service. They believe that customers will never love a company until the employees love it first. Their mission reads:

‘At American Express we have a mission to be the world’s most

respected service brand. To do this, we have to establish a culture that supports our team members, so they can provide exceptional service to our company.’

IKEA – their mission could have been a promise for beautiful, affordable furniture. Instead IKEA dream big with their mission:

‘To create a better everyday life for the many people. Our business ideas support this by offering a wide range of well-designed, functional home furnishing products at prices so low that as many people as possible will be able to afford them.’

Nike – view each customer as an athlete. Their mission is:

‘To bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world. If you have a body, you are an athlete.’

The Motor Neurone Disease Association (MNDA) – mission is just as applicable for not-for-profit organisations. This charity’s mission is:

‘We improve care and support for people with MND, their families and carers. We fund and promote research that leads to new understanding and treatments, and brings us closer to a cure for MND. We campaign and raise awareness so the needs of people with MND and everyone who cares for them are recognised and addressed by wider society.’

The mission forms a key part of the planning process and should enhance organisational performance:

- It acts as a source of inspiration and ideas for the organisation’s detailed plans and objectives.

- It can be used to assess the suitability of any proposed plans in terms of their fit with the organisation’s mission.

- It can impact the day to day workings of an organisation, guiding the organisational culture and business practices used.

Drucker

Drucker concluded that a mission statement should address four fundamental questions.

Test your understanding 1

Required:

What are the potential benefits to an organisation of setting a mission statement and what are the potential drawbacks or failings of a mission statement?

The lifespan of a mission

There are no set rules on how long a mission statement will be appropriate for an organisation. It should be reviewed periodically to ensure it still reflects the organisation’s environment.

If the market or key stakeholders have changed since the mission statement was written, then it may no longer be appropriate.

A change in the mission statement may result in new performance measures being established to monitor the achievement (or otherwise) of the new mission.

4.4 Strategic, tactical and operational plans

To enable an organisation to fulfil its mission, the mission must be translated into strategic, tactical and operational plans.

Each level should be consistent with the one above.

This process will involve moving from general broad aims to more specific objectives and ultimately to detailed targets.

In this we will focus on strategic and operational plans.

Comparing planning and control between strategic and operational levels

Illustration 2 – Strategic planning

Strategic planning is usually, but not always, concerned with the long-term. It raises the question of which business shall we be in? For example, a company specialising in production and sale of tobacco products may forecast a declining market for these products and may therefore decide to change its objectives to allow a progressive move into the leisure industry, which it considers to be expanding.

Strategic and operational planning

Planning

Strategic planning is characterised by the following:

- long-term

- considers the whole organisation as well as individual SBUs

- matches the activities of an organisation to its external environment

- matches the activities of an organisation to its resource capability and specifies future resource requirements

- will be affected by the expectations and values of all stakeholders, not just shareholders

- its complexity distinguishes strategic management from other aspects of management in an organisation. There are several reasons for this including:

– it involves a high degree of uncertainty

– it is likely to require an integrated approach to management – it may involve major change in the organisation.

Quite apart from strategic planning, the management of an organisation has to undertake a regular series of decisions on matters that are purely operational and short-term in character. Such decisions:

- are usually based on a given set of assets and resources

- do not usually involve the scope of an organisation’s activities

- rarely involve major change in the organisation

- are unlikely to involve major elements of uncertainty and the techniques used to help make such decisions often seek to minimise the impact of any uncertainty

- use standard management accounting techniques such as cost-volume-profit analysis, limiting factor analysis and linear programming.

Test your understanding 2

Required:

Is the activity of setting a profit-maximising selling price for a product a strategic or operational decision?

Give reasons for your answer.

The role of performance management in planning and control

Performance management is any activity that is designed to improve the organisation’s performance and ensure that its goals are met.

- Planning will take place first to establish an appropriate mission and objectives. These should be aligned with the organisation’s critical success factors (see Section 6).

- SMART objectives (targets) (see Section 5.3) should be set and appropriate performance indicators (performance measures) for each target established.

- Performance management techniques will then be used to put the most appropriate strategies in place in order to achieve the organisation’s mission and objectives.

- Finally, performance management techniques will aim to measure the achievement of the targets set and hence the mission and objectives and to recommend any improvement strategies required.

Performance management aims to direct and support the performance of all employees and departments so that the organisation’s goals are achieved. Therefore, any performance management system should be linked to performance measures at different levels of the hierarchy. One model of performance management that helps to link the different levels of the hierarchy is the performance pyramid.

The performance pyramid derives from the idea that an organisation operates at different levels, each of which has a different focus. However, it is vital that these levels support each other. It translates objectives from the top down and measures from the bottom up, the aim being that these are co-ordinated and support each other (this will be explored in more detail in 11).

5 Strategic (corporate) planning

We are now going to explore in more detail the role of strategic planning in performance management.

5.1 What is strategy?

The core of a company’s strategy is about choosing:

- where to compete and

- how to compete.

It is a means to achieve sustainable competitive advantage.

In terms of performance management, the test of a good strategy is whether it enables an organisation to use its resources and competencies advantageously in the context of an ever changing environment.

Strategic (or corporate) planning involves formulating, evaluating and selecting strategies to enable the preparation of a long-term plan of action and to attain objectives.

5.2 Strategic analysis, choice and implementation (rational model)

This three stage model of strategic planning is a useful framework for seeing the ‘bigger picture’ of performance management (and should be very familiar to you).

Each of these areas will be explored in greater detail throughout the course. However, it is worth noting that although strategy is still included in this exam, the main thrust in APM will be looking at where objectives come from, identifying critical success factors, choosing metrics and how to implement strategy. Theory will be secondary.

5.3 Clarifying corporate objectives

Corporate objectives concern the business as a whole and focus on the desired performance and results that a business intends to achieve.

Put more simply, objectives are the targets that an organisation sets out to achieve.

The first stage of the strategic planning process, strategic analysis, will generate a range of objectives, typically relating to:

- maximisation of shareholder wealth

- maximisation of sales

- growth

- survival

- research and development

- leadership

- quality of service

- contented workforce

- respect for the environment.

These need to be clarified in two respects:

- conflicts need to be resolved, e.g. profit versus environmental concerns

- to facilitate implementation and control, objectives need to be translated into SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time bound) targets.

Illustration 3 – SMART objectives

A statement such as ‘maximise profits’ would be of little use in corporate planning terms. The following would be far more helpful:

- achieve a growth in earnings per share (EPS) of 5% pa over the coming ten-year period

- obtain a turnover of $10 million within six years

- launch at least two new products per year.

5.4 Role of performance measurement in making strategic choices

The viability of a strategic choice should be assessed using three criteria:

The role of performance measurement in checking towards the objectives set

It is not enough merely to make plans and implement them.

- The results of the plans have to be measured and compared against stated objectives to assess the firm’s performance.

- Action can then be taken to remedy any shortfalls in performance.

Performance measurement is an ongoing process, which must react quickly to the changing circumstances of the firm and of the environment.

- Objectives, critical success factors and key performance indicators

6.1 Introduction

Once an organisation has established its objectives, it needs to identify the key factors and processes that will enable it to achieve those objectives.

Some aspects of performance are ‘nice to have’ but others are critical to the organisation if it is to succeed.

Critical success factors (CSFs) are the vital areas ‘where things must go right’ for the business in order for them to achieve their strategic objectives. The achievement of CSFs should allow the organisation to cope better than rivals with any changes in the competitive environment and to maximise performance.

Just as critical success factors are more important than other aspects of performance, not all performance indicators are created equal. The performance indicators that measure the most important aspects of performance are the key performance indicators.

Key performance indicators (KPIs) are the measures which indicate whether or not the CSFs are being achieved.

Illustration 4 – CSFs and KPIs

A parcel delivery service, such as DHL, may have an objective to increase revenue by 4% year on year. The business will establish CSFs and KPIs which are aligned to the achievement of this objective, for example:

| CSF | KPI |

| Speedy collection from | Collection from customers within |

| customers after their request | 3 hours of receiving the orders, in any |

| for a parcel to be delivered. | part of the country, for orders received |

| before 2.30pm on a working day. | |

| Rapid and reliable delivery. | Next day delivery for destinations within |

| the UK or delivery within 2 days for | |

| destinations in Europe. | |

6.2 CSFs

The organisation will need to have in place the core competencies that are required to achieve the CSFs, i.e. something that they are able to do that is difficult for competitors to follow.

There are five prime sources of CSFs:

- The structure of the industry – CSFs will be determined by the characteristics of the industry itself, e.g. in the car industry ‘efficient dealer network organisation’ will be important where as in the food processing industry ‘new product development’ will be important.

- Competitive strategy, industry position and geographic location

– Competitive strategies such as differentiation or cost leadership will impact CSFs.

– Industry position, e.g. a small company’s CSFs may be driven by a major competitor’s strategy.

– Geographical location will impact factors such as distribution costs and hence CSFs.

- Environmental factors – factors such as increasing fuel costs can have an impact on the choice of CSFs.

- Temporary factors – temporary internal factors may drive CSFs, e.g. a supermarket may have been forced to recall certain products due to contamination fears and may therefore generate a short term CSF of ensuring that such contamination does not happen again in the future.

- Functional managerial position – the function will affect the CSFs, g. production managers will be concerned with product quality and cost control.

6.3 Classifying CSFs

Further detail on classifying CSFs Internal versus external sources of CSFs

Every manager will have internal CSFs relating to the department and the people they manage. These CSFs can range across such diverse interests as human resource development or inventory control. The primary characteristic of such internal CSFs is that they deal with issues that are entirely within the manager’s sphere of influence and control.

External CSFs relate to issues that are generally less under the manager’s direct control such as the availability or price of a particular critical raw material or source of energy.

Monitoring versus building/adapting CSFs

Managers who are geared to producing short-term operating results invest considerable effort in tracking and guiding their organisation’s performance, and therefore employ monitoring CSFs to continuously scrutinise existing situations.

Almost all managers have some monitoring CSFs, which often include financially-oriented CSFs such as actual performance versus budget or the current status of product or service transaction cost. Another monitoring CSF might be personnel turnover rates.

Managers who are either in reasonable control of day-to-day operations, or who are insulated from such concerns, spend more time in a building or adapting mode. These people can be classified as future-oriented planners whose primary purpose is to implement major change programmes aimed at adapting the organisation to the perceived emerging environment.

Typical CSFs in this area might include the successful implementation of major recruitment and training efforts, or new product or service development programmes.

Test your understanding 4

The directors of Dream Ice Cream (DI), a successful ice cream producer, with a reputation as a quality supplier, have decided to enter the frozen yogurt market in its country of operation. It has set up a separate operation under the name of Dream Yogurt (DY). The following information is available:

- DY has recruited a management team but production staff will need to be recruited. There is some concern that there will not be staff available with the required knowledge of food production.

- DY has agreed to supply yogurts to Jacksons, a chain of supermarkets based in the home country. They have stipulated that delivery must take place within 24 hours of an order being sent.

- DY hopes to become a major national producer of frozen yogurts.

- DY produces four varieties of frozen yogurt at present; Mango Tango, Very Berry, Orange Burst and French Vanilla.

Required:

Explain five CSFs on which the directors must focus if DY is to achieve success in the marketplace.

(10 marks)

Student accountant article: visit the ACCA website, www.accaglobal.com, to review the article on ‘defining managers’ information requirements’.

6.4 KPIs

KPIs are essential to the achievement of strategy since:

‘what gets measured gets done’

i.e. things that are measured get done more often than things that are not measured.

Features of good performance measures

In addition, KPIs should be SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and time-bound).

Care must be taken when choosing what to measure and report. An unbalanced set of indicators may be valid for fulfilling the short-term needs of the organisation but will not necessarily result in long-term success. The balanced scorecard approach will seek to address this and is discussed in 11.

What gets measured gets done

In the previous section the quote “what gets measured gets done” was referred to. In some respects the statement seems obvious – measuring something gives you the information you need in order to make sure you actually achieve what you set out to do. Without a standard, there is no logical basis for making a decision or taking action.

However, there can be some problems with this approach:

- It assumes that staff have some motivation to deliver what is measured, whether due to the potential of positive feedback and/or rewards or the consequences of failure. The statement could thus be modified to say “What gets measured and fed back gets done well. What gets rewarded gets repeated.”

- It assumes that staff have been informed up front that the particular issue would be measured and have thus been able to change their behaviour.

- It assumes that the factor being measured can be directly influenced by staff. In many situations factors have elements that are not controllable – for example, sales volume is partly due to the state of the economy.

- It assumes that expectations and targets are seen to be fair and achievable – failure on either of these counts could result in staff giving up and not trying to meet targets.

- A significant potential problem is that a firm will focus on what is easy to measure, such as cost, but ultimately ignore factors that are more difficult to measure, such as customer perception. Albert Einstein reportedly had a sign on his office wall that stated: “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.”

- It implies that “what gets done” is what management wanted – for example, a focus on measuring profit may result in short termism at the expense of long term shareholder value.

- Measurement may foster unhealthy rivalry whereas before there was cooperation.

Student accountant article: visit the ACCA website, www.accaglobal.com, to review the article on ‘performance indicators’.

6.5 Past exam question

Some of the test your understandings in this material are shorter or more straightforward than questions in the APM exam. They are contained in the material for learning purposes and will help you to build your knowledge and confidence so that you are ready to tackle past exam questions during the revision phase.

However, it is useful to look at some past exam/exam standard questions right from the beginning of this course in order to understand how the areas covered may be tested in the real exam. You need to understand how to interpret the requirements read and understand the scenario and plan and structure your answer. You may not be able to tackle the entire question at this point but you should read and learn from the answer.

Note: requirement (d) has been included for completeness but the areas tested have not been covered in the material as yet.

Test your understanding 5

Film Productions Co (FP) is a small international company producing films for cinema release and also for sale on DVD or to television companies. FP deals with all areas of the production from casting, directing and managing the artists to negotiating distribution deals with cinema chains and TV channels. The industry is driven by the tastes of its films’ audience, which when accurately predicted can lead to high levels of profitability on a successful film.

The company’s stated mission is to ‘produce fantastic films that have mass appeal’. The company makes around $ 200 million of sales each year equally split between a share of cinema takings, DVD sales and TV rights. FP has released 32 films in the past five years. Each film costs an average of $18 million and takes 12 months to produce from initial commissioning through to the final version. Production control is important in order to hit certain key holiday periods for releasing films at the cinema or on DVD.

The company’s films have been moderately successful in winning industry awards although FP has never won any major award. Its aims have been primarily commercial with artistic considerations secondary.

The company uses a top-down approach to strategy development with objectives leading to critical success factors (CSFs) which must then be measured using performance indicators. Currently, the company has identified a number of critical success factors. The two most important of these are viewed as:

- improve audience satisfaction

- strengthen profitability in operations.

At the request of the board, the chief executive officer (CEO) has been reviewing this system in particular the role of CSFs. Generally, the CEO is worried that the ones chosen so far fail to capture all the factors affecting the business and wants to understand all possible sources for CSFs and what it means to categorise them into monitoring and building factors.

These CSFs will need to be measured and there must be systems in place to perform that role. The existing information system of the company is based on a fairly basic accounting package. However, the CEO has been considering greater investment in these systems and making more use of the company’s website in both driving forward the business’ links to its audience and in collecting data on them.

The CEO is planning a report to the board of Film Productions and has asked you to help by drafting certain sections of this report.

Required:

You are required to draft the sections of the CEO’s report answering the following questions:

- Explain the difference between the following two types of CSF: monitoring and building, using examples appropriate to FP.

(4 marks)

- Identify information that FP could use to set its CSFs and explain how it could be used giving two examples that would be appropriate to FP.

(6 marks)

- For each of the two critical success factors given in the question, identify two performance indicators (PIs) that could support measurement of their achievement and explain why each PI is relevant to the CSF.

(10 marks)

- Discuss the implications of your chosen PIs for the design and use of the company’s website, its management information system and its executive information system.

(9 marks)

2 professional marks will be awarded for appropriateness of style and structure of the answer.

(Total: 31 marks)

7 Long-term and short-term conflicts

Strategic planning is a long-term, top-down process. The decisions made can conflict with the short-term localised decisions:

- Divisional managers tend to be rewarded on the short-term results they achieve. Therefore, it will be difficult to motivate managers to achieve long-term strategic objectives.

- Divisional managers need to be able to take advantage of short-term unforeseen opportunities or avoid serious short-term crisis. Strict adherence to a strategy could limit their ability to do this.

Long-term and short-term conflicts

The whole concept of strategic planning explored earlier in this implies a certain top-down approach. Even in the era of divisional autonomy and employee empowerment it is difficult to imagine that a rigorous strategic planning regime could be associated with a bottom-up management culture. There is a potential for conflict here.

- The idea of divisional autonomy is that individual managers operate their business units as if they were independent businesses – seeking and exploiting local opportunities as they arise.

- Managers are rewarded in a manner which reflects the results they achieve.

- The pressures on management are for short-term results and ostensibly strategy is concerned with the long-term. Often it is difficult to motivate managers by setting long-term expectations.

- Long-term plans have to be set out in detail long before the period to which they apply. The rigidity of the long-term plan, particularly in regard to the rationing and scheduling of resources, may place the company in a position where it is unable to react to short-term unforeseen opportunities, or serious short-term crisis.

- Strict adherence to a strategy can limit flair and creativity. Operational managers may need to respond to local situations, avert trouble or improve a situation by quick action outside the strategy. If they then have to defend their actions against criticisms of acting ‘outside the plan’, irrespective of the resultant benefits, they are likely to become apathetic and indifferent.

- The adoption of corporate strategy requires a tacit acceptance by everyone that the interests of departments, activities and individuals are subordinate to the corporate interests. Department managers are required to consider the contribution to corporate profits or the reduction in corporate costs of any decision. They should not allow their decisions to be limited by short-term departmental parameters.

- It is only natural that local managers should seek personal advancement. A problem of strategic planning is identifying those areas where there may be a clash of interests and loyalties, and in assessing where an individual has allowed vested interests to dominate decisions.

Test your understanding 6

Required:

How might an organisation take steps to avoid conflict between strategic business plans and short-term localised decisions?

8 The changing role of the management accountant

8.1 What is strategic management accounting?

Strategic management accounting is a form of management accounting which aims to provide information that is relevant to the process of strategic planning and control. The focus is on both external and internal information and non-financial as well as financial factors.

The strategic management accountant plays a key role in performance management helping to determine the financial implications of an organisation’s activities and decisions and in ensuring that these activities are focused on shareholders’ needs for profit.

Test your understanding 7

A company selling wooden garden furniture in northern Europe is facing a number of problems:

- demand is seasonal

- it is sometimes difficult to forecast demand as it varies with the weather – more is sold in hot summers than when it is cooler or wetter

- the market is becoming more fashion-conscious with shorter product life cycles

- there is a growth in the use of non-traditional materials such as plastics.

As a result the company finds itself with high inventory levels of some items of furniture which are not selling, and is unable to meet demand for others. A decision is needed on the future strategic direction and possible options which have been identified are to:

- use largely temporary staff to manufacture products on a seasonal basis in response to fluctuations in demand – however it has been identified that this could result in quality problems

- automate production to enable seasonal production with minimum labour-related problems

- concentrate on producing premium products which are smaller volume but high-priced and less dependent on fashion.

Required:

How could strategic management accounting help with the decision making?

8.2 Changes in the role of the management accountant

The role of the management accountant has changed as a result of environmental pressures. Burns and Scapens studied how the role has changed in recent years.

- The role has changed focus from financial control to business support making the management accountant more of a generalist.

Management accountants may now spend much of their time as internal consultants and although they still produce standardised reports, more time is spent analysing and interpreting information rather than preparing reports.

- This new role has been called a hybrid accountant since the management accountant has a valuable combination of both accounting and operational/commercial knowledge.

- Traditionally, it was thought that accountants needed to be independent from operational managers in order to allow them to objectively judge and report their accounting information to senior managers. However, today accountants do not necessarily work in a separate accounting department but may be fully integrated into other departments, thus playing a key part in the operations and decision making process of the department.

Role of a management accountant

A scan of current job advertisements for management accountants would show that they are frequently being asked to:

- inform strategic decisions and formulate business strategies

- lead the organisation’s business risk management

- ensure the efficient use of financial and other resources

- advise on ways of improving business performance

- liaise with other managers to put the finance view in context

- train functional and business managers in budget management

- identify the implications of product and service changes

- work in cross-functional teams involved in strategic planning or new product development.

8.3 Driving forces for change

| Driving force | Explanation | ||||

| Management | | Head office has delegated much responsibility to the | |||

| structure | strategic business units thus reducing the | ||||

| involvement of management accountants in areas | |||||

| such as detailed budgeting. | |||||

| | The management accountant may now provide a link | ||||

| between the operational reports, the financial | |||||

| consequences and the strategic outcomes desired | |||||

| by the board. | |||||

| Technology | | Management Information Systems (MIS) allow | |||

| access for users across the organisation to input | |||||

| data and run reports giving the type of analysis once | |||||

| only provided by the management accountant. | |||||

| Competition | | The competitive environment has driven | |||

| organisations to take a more strategic focus. | |||||

| | Management accountants no longer focus their | ||||

| efforts on the final profit figure (this is seen as short- | |||||

| termism) but focus on a number of measures which | |||||

| try to capture long-term performance. | |||||

| 24 | |||||

8.4 Benefits of the changes for performance management

- From an organisation’s perspective, the accountant will be a guide to the strategic business unit manager to ensure that strategic goals are reflected in performance management.

- The management accountant will take a supporting role in assisting strategic business unit managers in getting the most from their management information system. This will entail the accountant understanding the needs of the particular manager and then working with them to extract valuable reports from the management information system.

- The management accountant can develop a range of performance measures to capture the different factors that will drive its success.

8.5 Role of the management accountant in providing information to stakeholders

Introduction

The demands placed on management accountants have grown in recognition of significant sustainability challenges.

Illustration 5 – Ben and Jerry’s

Let’s revisit mission. The ice -cream manufacturer, Ben and Jerry’s operate a three part mission that aims to create linked prosperity for everyone that’s connected to the business: suppliers, employees, farmers, franchisees, customers and neighbours alike.

‘Our Product Mission drives us to make fantastic ice-cream – for its own sake.’

‘Our Economic Mission asks us to manage our Company for sustainable financial growth.’

‘Our Social Mission compels us to use our Company in innovative ways to make the world a better place.’

These demands require a rich supply of information, capable of informing stakeholders of the financial and non-financial impact of the company’s decisions.

Conventional management accounting systems often failed to provide this information.

The triple bottom line

Whilst all businesses are used to monitoring their profit figures, there are also environmental and social aspects to consider in the longer term.

The triple bottom line focuses on economic, environmental and social areas of concern.

| Area of concern | Explanation | |

| Economic | | The management accountant must monitor the |

| performance | financial performance of the organisation to ensure | |

| its continued prosperity and fulfilment of | ||

| shareholders’ needs. | ||

| Environmental | | Improved environmental practices may include taking |

| performance | steps to reduce waste, increase recycling and use | |

| energy efficient equipment. | ||

| | The management accountant must monitor the costs | |

| and benefits of such actions to ensure that the needs | ||

| of stakeholders are being met. | ||

| Social | | Many examples exist such as a contribution by a |

| performance | company to community projects. | |

| | Perhaps harder to measure than the economic and | |

| environmental aspects. | ||

| | Many activities don’t have to cost the organisation | |

| much (for example, giving staff time off every year to | ||

| volunteer for charitable causes) but can have far | ||

| reaching social benefits. | ||

| | The management accountant must monitor the costs | |

| and benefits (as above). | ||

The management accountant has an important role in preparing sustainability reports and capturing non-financial information.

There is a growing trend for companies to issue sustainability reports, sometimes as part of traditional financial reports. The problem with this type of ‘add-on’ to the annual financial report is that it is very selective and may communicate only the good news for readers, ignoring or obscuring the bad.

Illustration 6 – Enron

US energy giant Enron was well known for its social and environmental work and published reports on all the good work they did in this area.

However, at the same time it was misleading its stakeholders about its profits. When the truth emerged, it led to the company’s collapse in 2001 and top executives were jailed for conspiracy and fraud.

All of its community and environmental work was undermined by the fact that it was carried out by a company with dishonest business practices.

9 Integrated Reporting

9.1 Introduction

To tackle the problem discussed above, a new approach is being recommended called integrated reporting (IR).

With IR, instead of having environmental and social issues reported in a separate section of the annual report, or a standalone ‘sustainability’ report, the idea is that one report should capture the strategic and operational actions of management in its holistic approach to business and stakeholder ‘wellbeing’.

9.2 The management accountant’s role in providing key performance information for IR

The management accountant must now be able to collaborate with top management in the integration of financial wellbeing with community and stakeholder wellbeing. This is a more strategic view considering factors that drive long-term performance.

IR will bring statutory reporting closer to the management accountant and will make management accountants even more important in bridging the gap between stakeholders and the company’s reports.

The management accountant will be expected to produce information that:

- is a balance between quantitative and qualitative information. The information system must be able to capture both financial and non-financial measures

- links past, present and future performance. The forward looking nature will require more forecasted information

- considers the regulatory impacts on performance

- provides an analysis of opportunities and risks that could impact in the future

- considers how resources should be best allocated

- is tailored to the specific business situation but remains concise.

There is clearly a need for the profession to accept the challenge for being the mechanism for a new type of transparency and accountability; one that incorporates social and environmental impacts as well as economic ones.

The role of the management accountant in sustainability is as yet not well established. However, it is anticipated that over time, IR will become the corporate reporting norm. This will offer a productive and rewarding future, not only for the management accountant but for society as a whole.

9.3 The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC)

The IIRC was formed in August 2010 and aims to create a globally accepted framework for a process that results in communication by an organisation about value creation over time.

The IIRC seeks to secure the adoption of an Integrated Reporting Framework (an alternative to the recommendations by the GRI) by report preparers. The Framework sets out several guiding principles and content elements that have to be considered when preparing an integrated report.

Illustration 7 – Guiding principles

There are seven guiding principles, as follows:

Strategic focus and future orientation – the report should provide and insight into the organisation’s strategy and how it relates to the organisation’s ability to create value in the short, medium and long term.

Connectivity of information – the report should show a holistic picture of the combination, inter-relatedness and dependencies between the factors that affect the organisation’s ability to create value over time.

Stakeholder relationships – the report should provide an insight into the nature and quality of the organisation’s relationships with its stakeholders.

Materiality – the report should disclose information about matters that substantively affect the organisation’s ability to create value.

Conciseness – the report should be concise and include relevant information only.

Reliability and completeness – the report should include all material matters, both positive and negative, in a balanced way and without material error.

Consistency and comparability – the report should be consistent and comparable over time.

Illustration 8 – Content elements

There are eight content elements. The first six are particularly relevant to APM.

Organisational overview and external environment – what does the organisation do and what are the circumstances under which it operates? The organisation’s mission and objectives, stakeholder analysis and PEST analysis would be relevant in this section.

Risks and opportunities – what are the risks and opportunities, both internal and external, that affect the organisation’s ability to create value over the short, medium and long term and how is the organisation dealing with them?

Strategy and resource allocation – where does the organisation want to go and how does it intend to get there? This section may make use of Porter’s 5 Forces, the BCG matrix and the value chain.

Business model – what is the organisation’s business model, i.e. what activities will it carry out to create value? Many of the performance management models (such as the value chain) and methods (such as BPR, VBM and ABM) are relevant here.

Future outlook – what challenges and uncertainties is the organisation likely to encounter in pursuing its strategy and what are the implications for future performance? PEST and Porter’s 5 Forces are likely to be particularly relevant here.

Performance – to what extent has the organisation achieved its strategic objectives for the period? The most appropriate performance indicators should be chosen here.

Governance – how does the organisation’s governance structure support its ability to create value in the short, medium and long term?

Basis of preparation and presentation – how does the organisation determine what matters to include in the integrated report and are such matters quantified or evaluated?

The models and methods above will be discussed later on in the text.

Student accountant article: visit the ACCA website, www.accaglobal.com, to review the article on ‘integrated reporting’.

9.4 IR and capital

The IR Framework recognises the importance of looking at financial and sustainability performance in an integrated way – one that emphasises the relationships between what it identifies as the “six capitals”:

- Financial capital

This is what we traditionally think of as ‘capital’ – e.g. shares, bonds or banknotes. It enables the other types of Capital described below to be owned and traded.

- Manufactured capital

This form of capital can be described as comprising of material goods, or fixed assets which contribute to the production process rather than being the output itself – e.g. tools, machines and buildings.

- Intellectual capital

This form of capital can be described as the value of a company or organisation’s employee knowledge, business training and any proprietary information that may provide the company with a competitive advantage.

- Human capital

This can be described as consisting of people’s health, knowledge, skills and motivation. All these things are needed for productive work.

- Social and relationship capital

This can be described as being concerned with the institutions that help maintain and develop human capital in partnership with others;

e.g. Families, communities, businesses, trade unions, schools, and voluntary organisations.

- Natural capital

This can be described as any stock or flow of energy and material within the environment that produces goods and services. It includes resources of a renewable and non-renewable materials e.g. land, water, energy and those factors that absorb, neutralise or recycle wastes and processes – e.g. climate regulation, climate change, CO2 emissions.

The fundamental assumption of the IR Framework is that each of these types of capital – whether internal or external to the business, tangible or intangible – represents a potential source of value that must be managed for the long run in order to deliver sustainable value creation.

As well as external reporting to a range of stakeholders, the principles of IR can be extended to performance management systems. This is sometimes referred to as ‘internal IR’.

An emphasis on these types of capital could result in more focussed performance management in the following ways:

- KPIs can be set up for each of the six capitals, ensuring that each of the drivers of sustainable value creation are monitored, controlled and developed.

- These can be developed further to show how the KPIs connect with different capitals, interact with, and impact each other.

- The interaction and inter-connectedness of these indicators should then be reflected in greater integration and cooperation between different functions and operations within the firm.

- This should result in greater transparency of internal communications allowing departments to appreciate better the wider implications of their activities.

- Together this should result in better decision making and value creation over the longer term.

Test your understanding 8

For each of the six capitals outlined in the Integrated Reporting

Framework, suggest appropriate KPIs.

9.5 The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)

The most accepted framework for reporting sustainability is the GRI’s Sustainability Reporting Guidelines, the latest of which ‘G4’ – the fourth of the guidelines – was issued in May 2013. The G4 Guidelines consist of principles and disclosure items.

- The principles help to define report content, quality of the report and give guidance on how to set the report boundary.

- The disclosure items include disclosures on management of issues as well as performance indicators themselves.

Reporting principles and disclosures

Reporting principles

Reporting principles are essentially the required characteristics of the Report Content and the Report Quality. The Principles for Defining Report Content are given as:

- Stakeholder Inclusiveness

- Sustainability Context

- Materiality

The Principles for Defining Report Quality are given as:

- Balance

- Comparability

- Accuracy

- Timeliness

- Clarity

Standard disclosures

Two types of disclosure are required: General standard disclosures:

- Strategy and Analysis

- Organisational Profile

- Identified Material Aspects and Boundaries

- Stakeholder Engagement

- Report profile

- Governance

- Ethics and Integrity.

Specific Standard Disclosures

- Disclosures on Management’s Approach

The G4 guidelines encourage disclosure of various ‘aspects’ in the three categories: Economic, Environmental and Social.

Illustration 9 – Categories and aspects in the G4 guidelines

Examples of the aspects grouped by category are:

Economic

- Economic Performance

- Market Presence

Environmental

- Materials, energy and water

- Biodiversity

- Emissions

- Effluents and Waste

Social – this category is split into four sub-categories, each with several aspects associated with it as follows:

Labour Practices and Decent Work

- Labour/Management Relations

- Occupational Health and Safety

- Training and Education

- Diversity and Equal Opportunity

Human rights

- Non-discrimination

- Child Labour

- Human Rights Grievance Mechanisms.

Society

- Local Communities

- Anti-corruption

Product responsibility

- Customer Health and Safety

- Product and Service Labelling

10 Benchmarking performance

10.1 What is benchmarking?

Benchmarking is the process of identifying best practice in relation to the products (or services) and the processes by which those products (or services) are created and delivered. The objective of benchmarking is to understand and evaluate the current position of a business or organisation in relation to best practice and to identify areas and means of performance improvement.

10.2 Types of benchmarks

There are three basic types:

- Internal: this is where another function or department of the organisation is used as a benchmark.

Can be straightforward but may lack innovative solutions due to there being no external focus.

Furthermore it is difficult to use such benchmarks to understand if the company as a whole has a competitive advantage.

- Competitor: uses a direct competitor in the same industry with the same or similar processes as the benchmark.

The biggest problem will be obtaining information from the competitor. However, such benchmarks will be much more useful for indicating relative competitive advantage or the lack of it.

- Process or activity: focuses on a similar process in another company which is not a direct competitor.

Can prove easier to obtain information from a non-competitor and can still find innovative solutions.

Illustration 10 – Process benchmarking at Xerox

Among the pioneers in the benchmarking ‘movement’ were Xerox, Motorola, IBM and AT&T. The best known is the Xerox Corporation.

Some years ago, Xerox confronted its own unsatisfactory performance in product warehousing and distribution. It did so by identifying the organisation it considered to be the very best at warehousing and distribution, in the hope that ‘best practices’ could be adapted from this model. The business judged to provide a model of best practice in this area was L L Bean, a catalogue merchant (i.e. it existed in an unrelated sector). Xerox approached Bean with a request that the two engage in a co-operative benchmarking project. The request was granted and the project yielded major insights in inventory arrangement and order processing, resulting in major gains for Xerox when these insights were adapted to its own operations.

Strategic, functional and operational benchmarks

Benchmarks could include the following:

Strategic benchmarks

- market share

- return on assets

- gross profit margin on sales.

Functional benchmarks

- % deliveries on time

- order costs per order

- order turnaround time

- average stockholding per order.

Operational benchmarks

These are at a level below functional benchmarks. They yield the reasons for a functional performance gap. An organisation has to understand the benchmarks at the operational level in order to identify the corrective actions needed to close the performance gap.

10.3 The benchmarking process

Benchmarking and the strategic planning process

Benchmarking can be used in all three areas of the strategic planning process:

- Strategic analysis – a company’s mission may be to be ‘the premium provider of its products’ but without comparison through benchmarking how will they know if they are delivering premium products? In addition, a company’s position can be summarised in a SWOT analysis. Each of these factors can be identified through benchmarking and any gaps identified.

- Strategic choice – benchmarking can help in assessing generic strategy. For example, an organisation may compare its costs to the leading competitor. If the organisation cannot better or equal those results then cost leadership is an inappropriate strategy to pursue.

- Strategic implementation – for example, budgetary targets should be benchmarked against other organisations to ensure that they are both challenging and attainable.

10.5 Benchmarking metrics

Once an organisation has decided which aspects of its performance should be benchmarked, it must then establish metrics for these, i.e. how can performance be measured? Some areas will be easy to measure (such as material used) where as others will be more difficult (such as customer service).

Illustration 11 – Benchmarking success at Kelloggs

Kelloggs’ factories all use the same monitoring techniques, so it is possible to compare performance between sites, although there are always some things that are done differently.

They can interrogate this information to improve performance across every site. As things have improved, Kelloggs have also had to reassess their baseline figures and develop more sophisticated tools to monitor performance to ensure they continue to make progress.

They have seen a 20% increase in productivity in a six year period using this system.

10.6 Benchmarking evaluation

| Benefits | Drawbacks | |||||

| | Identifies gaps in performance | | Best practice companies may be | |||

| and sets targets which are | unwilling to share data. | |||||

| challenging but achievable. | | Lack of commitment by | ||||

| | ||||||

| Can help in assessing its current | management and staff. Staff | |||||

| strategic position (more on | need to be reassured that their | |||||

| SWOT analysis in section 11.1). | status, remuneration and working | |||||

| conditions will not suffer. | ||||||

| 36 | ||||||

- A method for learning and applying best practices.

- Encourages continuous improvement.

- A method of learning from the success of others.

- Can help to assess generic strategy.

- Minimises complacency and self-satisfaction with your own performance and can provide an early warning of competitive disadvantage.

- Identifying best practice is difficult.

- Costly in terms of time and money.

- What is best today may not be so tomorrow.

- Differences, for example in accounting treatment, may make comparisons meaningless.

- Too much attention is paid to the aspects of performance that are measured as a result of the benchmarking exercise, to the detriment of the organisation’s overall performance.

Performance comparison with the competition

Comparative analysis can be usefully applied to any value activity which underpins the competitive strategy of an organisation, an industry or a nation.

To find out the level of investment in fixed assets of competitors, the business can use physical observation, information from trade press or trade association announcements, supplier press releases as well as their externally published financial statements, to build a clear picture of the relative scale, capacity, age and cost for each competitor.

The method of operating these assets, in terms of hours and shift patterns, can be established by observation, discussions with suppliers and customers or by asking existing or ex-employees of the particular competitor. If the method of operating can be ascertained it should enable a combination of internal personnel management and industrial engineering managers to work out the likely relative differences in labour costs. The rates of pay and conditions can generally be found with reference to nationally negotiated agreements, local and national press advertising for employees, trade and employment associations and recruitment consultants. When this cost is used alongside an intelligent assessment of how many employees would be needed by the competitor in each area, given their equipment and other resources, a good idea of the labour costs can be obtained.

Another difference which should be noted is the nature of the competitors’ costs as well as their relative levels. Where a competitor has a lower level of committed fixed costs, such as lower fixed labour costs due to a larger proportion of temporary workers, it may be able to respond more quickly to a downturn in demand by rapidly laying off the temporary staff. Equally, in a tight labour market and with rising sales, it may have to increase its pay levels to attract new workers.

In some industries, one part of the competitor analysis is surprisingly direct. Each new competitive product is purchased on a regular basis and then systematically taken apart, so that each component can be identified as well as the processes used to put the parts together. The respective areas of the business will then assess the costs associated with each element so that a complete product cost can be found for the competitive product.

A comparison of similar value activities between organisations is useful when the strategic context is taken into consideration. For example, a straight comparison of resource deployment between two competitive organisations may reveal quite different situations in the labour cost as a percentage of the total cost. The conclusions drawn from this, however, depend upon circumstances. If the firms are competing largely on the basis of price, then differentials in these costs could be crucial. In contrast, the additional use of labour by one organisation may be an essential support for the special services provided which differentiate that organisation from its competitors.

One danger of inter-firm analysis is that the company may overlook the fact that the whole industry is performing badly, and is losing out competitively to other countries with better resources or even other industries which can satisfy customers’ needs in different ways. Therefore, if an industry comparison is performed it should make some assessment of how the resource utilisation compares with other countries and industries. This can be done by obtaining a measurement of stock turnover or yield from raw materials.

Benchmarking against competitors involves the gathering of a range of information about them. For quoted companies financial information will generally be reasonably easy to obtain, from published accounts and the financial press. Some product information may be obtained by acquiring their products and examining them in detail to ascertain the components used and their construction (‘reverse engineering’). Literature will also be available, for example in the form of brochures and trade journals.

However, most non-financial information, concerning areas such as competitors’ processes, customer and supplier relationships and customer satisfaction will not be so readily available. To overcome this problem, benchmarking exercises are generally carried out with organisations taken from within the same group of companies (intragroup benchmarking) or from similar but non-competing industries (inter-industry benchmarking).

Question practice

The following question is an exam standard and style question on benchmarking. Make sure that you take the time to attempt this question and to review the recommended answer.

Test your understanding 9

AV is a charitable organisation, the primary objective of which is to meet the accommodation needs of persons within its locality.

In an attempt to improve its performance, AV’s directors have started to carry out a benchmarking exercise. They have identified a company called BW which is a profit seeking private provider of rented accommodation.

BW has provided some operational and financial data which is summarised below along with the most recent results for AV for the year ended 31 May 20X4.

Income and expenditure accounts for the year ended 31 May 20X4 were as follows:

| AV ($) | BW ($) | |

| Rents received | 2,386,852 | 2,500,000 |

| Less: | ||

| Staff and management costs | 450,000 | 620,000 |

| Major repairs and planned maintenance | 682,400 | 202,200 |

| Day-to-day repairs | 478,320 | 127,600 |

| Sundry operating costs | 305,500 | 235,000 |

| Net interest payable and other similar charges | 526,222 | 750,000 |

| –––––––– | –––––––– | |

| Total costs | 2,442,442 | 1,934,800 |

| Operating (deficit/surplus) | (55,590) | 565,200 |

Operating information in respect of the year ended 31 May 20X4 was as follows:

1 Property and rental information:

| AV – size of | AV – number | AV – rent payable | BW – number |

| property | of properties | per week | of properties |

| ($) | |||

| 1 bedroom | 80 | 40 | 40 |

| 2 bedrooms | 160 | 45 | 80 |

| 3 bedrooms | 500 | 50 | 280 |

| 4 bedrooms | 160 | 70 | nil |

AV had certain properties that were unoccupied during part of the year. The rents lost as a consequence of unoccupied properties amounted to $36,348. BW did not have any unoccupied properties at any point during the year.

2 Staff salaries were payable as follows:

| AV – number | AV – salary per | BW – number BW – salary per | |||

| of staff | staff member | of staff | staff member | ||

| per year | per year | ||||

| $ | $ | $ | |||

| 2 | 35,000 | 3 | 50,000 | ||

| 2 | 25,000 | 2 | 35,000 | ||

| 3 | 20,000 | 20 | 20,000 | ||

| 18 | 15,000 | – | – | ||

| 3 Planned maintenance and major repairs undertaken | |||||

| Nature of work | AV – | AV – | BW – | BW – | |

| number of | cost per | number of | cost per | ||

| properties | property | properties | property | ||

| ($) | ($) | ||||

| Miscellaneous | 20 | 1,250 | – | – | |

| construction work | |||||

| Fitted kitchen | 90 | 2,610 | 10 | 5,220 | |

| replacements (all are | |||||

| the same size) | |||||

| Heating upgrades/ | 15 | 1,500 | – | – | |

| replacements | |||||

| Replacement sets of | 100 | 4,000 | 25 | 6,000 | |

| windows and doors | |||||

| for 3 bedroomed | |||||

| properties | |||||

All expenditure on planned maintenance and major repairs may be regarded as revenue expenditure.

4 Day-to-day repairs information:

| Classification | AV – number of | AV – total | BW – number of |

| of repair | repairs undertaken | cost | repairs undertaken |

| $ | |||

| Emergency | 960 | 134,400 | 320 |

| Urgent | 1,880 | 225,600 | 752 |

| Non-urgent | 1,020 | 118,320 | 204 |

Each repair undertaken by BW costs the same irrespective of classification of repair.

Required:

- Assess the progress of the benchmarking exercise to date, explaining the actions that have been undertaken and those that are still required.

(8 marks)

- Evaluate, as far as possible, AV’s benchmarked position.

(9 marks)

- Evaluate the benchmarking technique being used and discuss whether BW is a suitable benchmarking partner for AV to use.

(8 marks)

Student accountant article: visit the ACCA website, www.accaglobal.com to review the article on ‘benchmarking’.

11 Models used in the performance management process

A number of models can assist in the performance management process.

These include:

- SWOT analysis

- Boston Consulting Group

- Porter’s generic strategies

- Porter’s 5 Forces and

- the balanced scorecard.

The first three of these are discussed below. Porter’s 5 Forces is covered in 2 and the balanced scorecard is discussed in 11.

11.1 SWOT analysis

The purpose of SWOT analysis (corporate appraisal) is to provide a summarised analysis of the company’s present situation in the market place. It can also be used to identify CSFs and KPIs.

Using a SWOT analysis

Once a SWOT analysis has been carried out strategies can be developed that:

- neutralise weaknesses or convert them into strengths.

- convert threats into opportunities.

- match strengths with opportunities – a strength is of little use without an opportunity.

Test your understanding 10

Required:

What types of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats would a ‘no frills’ airline have?

SWOT analysis and the performance management process

SWOT analysis helps an organisation to understand its environment and its internal capacities and hence to evaluate the potential strategic options it could pursue in its quest to improve organisational performance and to close any performance gaps that exist.

It can also help an organisation to identify key aspects of performance (CSFs) that need measuring (through the establishment of KPIs).

Finally, it can help in determining the information needs of the business in relation to measuring and reporting on the KPIs set.

Test your understanding 11

Envie Co owns a chain of retail clothing stores specialising in ladies’ designer fashion and accessories. Jane Smith, the original founder, has been pleasantly surprised by the continuing growth in the fashion industry during the last decade.

The company was established 12 years ago, originally with one store in the capital city. Jane’s design skills and entrepreneurial skills have been the driving force behind the expansion. Due to unique designs and good quality control, the business now has ten stores in various cities.

Each store has a shop manger that is completely responsible for managing the staff and stock levels within each store. They produce monthly reports on sales. Some stores are continually late in supplying their monthly figures.

Envie runs several analysis programmes to enable management information to be collated. The information typically provides statistical data on sales trends between categories of items and stores. The analysis and preparation of these reports are conducted in the marketing department. In some cases the information is out of date in terms of trends and variations.

As the business has developed Jane has used the service of a local IT company to implement and develop their systems. She now wants to invest in website development with the view of reaching global markets.

Required:

- Construct a SWOT analysis with reference to the proposal of website development.

- Explain how the use of SWOT analysis may be of assistance to Envie Co’s performance management and measurement process.

11.2 Boston Consulting Group (BCG)

The BCG matrix shows whether the firm has a balanced portfolio in terms of the products it offers and the market sectors it operates in. The matrix is constructed using the following steps:

| 1 | Divide the business into divisions/strategic business units or products | |||||||

| 2 | Allocate each of these to the matrix. | |||||||

| 3 | Assess the prospects of each division or product. | |||||||

| 4 | Develop strategies and targets for each division or product. | |||||||

| Star | Problem child | |||||||

| | Large share of high- | | Small share of high- | |||||

| growth market. | growth market. | |||||||

| High | | High reinvestment rate | | Large investment | ||||

| required to hold/build | required to grow (so | |||||||

| position. | cash user). | |||||||

| Market | | Moderate cash flow. | | Or divest. | ||||

| growth | Cash cow | Dog | ||||||

| | Large share of low- | | Small share of low- | |||||

| growth market. | growth market. | |||||||

| Low | | Cash generator. | | Moderate or negative | ||||

| | Strategy is minimal | cash flow. | ||||||

| | ||||||||

| investment to keep the | Divest. | |||||||

| product going. | ||||||||

| High | Relative market share | Low | ||||||

If the relevant information is available, market growth and relative market share should be calculated as follows:

- Market growth = the % increase/decrease in annual market revenue

Note: if market revenue is given for a number of successive years the average % increase/decrease in annual market revenue can be calculated as follows:

1 + g = n√ most recent market revenue ÷ earliest market revenue

where g = the increase/decrease in annual market revenue as a decimal and

n = the number of periods of growth

As a guide, 10% is often used as the dividing line between high and low growth. However, this is a general guide only – do refer to and use the information given in the scenario.

- Relative market share = division’s market share ÷ largest competitor’s market share

where divisional market share = divisional revenue ÷ market revenue

A relative market share greater than 1 indicates that the division or product is the market leader. 1 can be used as the dividing line between high and low market share. However, this is a general guide only – do refer to and use the information given in the scenario.

Factors to consider for performance management

When conducting a BCG assessment an organisation should consider:

- how to manage the different categories in order to optimise the performance of the organisation.

- what performance indicators are required for each category.

- the alignment of the performance indicators with the objectives of the organisation and the individuals within it.

- how to measure market growth and relative market share and the reliability of these measurements.

BCG evaluation

| Benefits | Drawbacks | |||||

| | Ensures that a balanced portfolio | | Too simplistic, i.e. market growth | |||

| of products or divisions exists, | is just one indicator of industry | |||||

| i.e. are there enough cash cows | attractiveness and market share | |||||

| to support our question marks | is just one indicator of | |||||

| and stars? Are there a minimum | competitive advantage. Other | |||||

| number of dogs? | factors will also be determinants | |||||

| | Can use to manage divisions in | of profit. | ||||

| | ||||||

| different ways, e.g. divisions in a | Designed as a tool for product | |||||

| mature market should focus on | portfolio analysis rather than | |||||

| cost control and cash generation. | performance measurement. | |||||

| 44 | ||||||

| 1 | ||||||

| | Metrics used by the division can | | Downgrades traditional measures | |||

| be in line with the analysis, e.g. | such as profit and so may not be | |||||

| metrics for high growth prospects | aligned with shareholder’s | |||||

| may be based on profit and ROI | objectives. | |||||

| and metrics for lower growth | | Determining what ‘high’ and ‘low’ | ||||

| prospects will focus on margin | ||||||

| growth and share mean in | ||||||

| and cash generation. | ||||||

| different situations is difficult. | ||||||

| | Looks at the portfolio of divisions | |||||

| | Does not consider links between | |||||

| or products as a whole rather | ||||||

| business units, e.g. a dog may be | ||||||

| than assessing the performance | ||||||

| required to complete a product | ||||||

| of each one separately. | ||||||

| range. | ||||||

| | Can be used to assess | |||||

| performance, e.g. if an | ||||||

| organisation consists mainly of | ||||||

| cash cows we would expect to | ||||||

| see static or low growth in | ||||||

| revenue. | ||||||

Test your understanding 12

Food For Thought (FFT) has been established for over 20 years and has a wide range of food products. The company’s objective is the maximisation of shareholder wealth.

The organisation has four divisions:

- Premier

- Organic

- Baby

The Premier division manufactures a range of very high quality food products, which are sold to a leading supermarket, with stores in every major city in the country. Due to the specialist nature of the ingredients these products have a very short life cycle.

The Organic division manufactures a narrow range of food products for a well-established Organic brand label.

The Baby division manufactures specialist foods for infants, which are sold to the largest UK Baby retail store.

The Convenience division manufactures low fat ready-made meals for the local council.

FFT’s board have decided to perform a Boston Consulting Group (BCG)

analysis to understand whether they have right mix of businesses.

The following revenue data has been gathered:

| Year ending 31st March: | ||||||

| $m | ||||||

| 20X3 | 20X4 | 20X5 | 20X6 | 20X7 | ||

| Premier | Market size | 180 | 210 | 260 | 275 | 310 |

| Sales revenue | 10 | 12 | 18 | 25 | 30 | |

| Organic | Market size | 18.9 | 19.3 | 19.6 | 19.8 | 20.4 |

| Sales revenue | 13.5 | 14 | 14.5 | 15 | 16 | |

| Baby | Market size | 65 | 69 | 78 | 92 | 96 |

| Sales revenue | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3 | |

| Convenience | Market size | 26 | 27.2 | 27.6 | 28 | 29 |

| Sales revenue | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.9 | |

The management accountant has also collected the following information for 20X7 for comparison purposes.

Largest competitor % share

Premier 17%

Organic 20%

Baby 25%

Convenience 31%

Each of division’s performance is measured using EVA. The divisional manager’s remuneration package contains a bonus element which is based on the achievement of the division’s cost budget (this is set at board level).

Required:

Using the BCG matrix assess the competitive position of Food For Thought. Evaluate the divisional manager’s remuneration package in light of the divisional performance system and your BCG analysis.

Measurement problems using the BCG matric

There are a number of measurement problems regarding the BCG growth share matrix.

Measurement problems inherent in the model

The BCG matrix is a model and the weakness of any model is inherent in its assumptions. For example many strategists are of the opinion that the axes of the model are much too simplistic when trying to measure market attractiveness and competitive strength.

The model implies that competitive strength is indicated by relative market share. This would imply that economies of scale and/or the experience curve are usually dominating factors in markets and that market share is achieved through cost leadership. However other factors such as strength of brands, perceived product/service quality and costs structures also contribute to competitive strength.

Likewise the model implies that the attractiveness of the marketplace is indicated by the growth rate of the market. This is not necessarily the case as organisations that lack the necessary capital resources may find low-growth markets an attractive proposition especially as they tend to have a lower risk profile than hi-growth markets.

Measurement issues when applying the model

The main measurement problem when trying to apply the model lies in defining the market. The model requires management to define the market place within which a business is trading in order that its rate of growth and relative market share can be calculated.

Even having defined the appropriate market segment, ideally growth needs to be an estimate of future growth. This could involve a range of approaches, including analysing historic growth, time series analysis and looking at underlying drivers using a PEST analysis. Alternatively it could also include evaluating budgets and forecasts in terms of increasing potential customers, new customers and so on.

Similarly there may be issues in identifying the lead competitor within that market to enable a calculation of relative market share to be made. This can prove problematic in comparing competitors since if they supply different products and services then the absence of a consistent basis for comparison impairs the usefulness of the model.