Meaning of financial resources

Finance is the science of funds management. The general areas of finance are business finance, personal finance, and public finance. Finance includes saving money and often includes lending money. The field of finance deals with the concepts of time, money, risk and how they are interrelated. It also deals with how money is spent and budgeted.

One facet of finance is through individuals and business organizations, which deposit money in a bank. The bank then lends the money out to other individuals or corporations for consumption or investment and charges interest on the loans.

Loans have become increasingly packaged for resale, meaning that an investor buys the loan (debt) from a bank or directly from a corporation. Bonds are debt instruments sold to investors for organizations such as companies, governments or charities. The investor can then hold the debt and collect the interest or sell the debt on a secondary market. Banks are the main facilitators of funding through the provision of credit, although private equity, mutual funds, hedge funds, and other organizations have become important as they invest in various forms of debt. Financial assets, known as investments, are financially managed with careful attention to financial risk management to control financial risk. Financial instruments allow many forms of securitized assets to be traded on securities exchanges such as stock exchanges, including debt such as bonds as well as equity in publicly traded corporations.

Central banks, such as the Federal Reserve System banks in the United States and Bank of England in the United Kingdom, are strong players in public finance, acting as lenders of last resort as well as strong influences on monetary and credit conditions in the economy

Sources of finance

Sourcing money may be done for a variety of reasons. Traditional areas of need may be for capital asset acquirement – new machinery or the construction of a new building or depot. The development of new products can be enormously costly and here again capital may be required. Normally, such developments are financed internally, whereas capital for the acquisition of machinery may come from external sources. In this day and age of tight liquidity, many organizations have to look for short term capital in the way of overdraft or loans in order to provide a cash flow cushion. Interest rates can vary from organization to organization and also according to purpose.

A company might raise new funds from the following sources:

The capital markets:

- new share issues, for example, by companies acquiring a stock market listing for the first time

- rights issues

- Loan stock

- Retained earnings

- Bank borrowing

- Government sources

- Business expansion scheme funds

- Venture capital

- Franchising.

Ordinary (equity) shares

Ordinary shares are issued to the owners of a company. They have a nominal or ‘face’ value, typically of $1 or 50 cents. The market value of a quoted company’s shares bears no relationship to their nominal value, except that when ordinary shares are issued for cash, the issue price must be equal to or be more than the nominal value of the shares.

Deferred ordinary shares

are a form of ordinary shares, which are entitled to a dividend only after a certain date or if profits rise above a certain amount. Voting rights might also differ from those attached to other ordinary shares.

Ordinary shareholders put funds into their company:

- by paying for a new issue of shares

- through retained profits.

Simply retaining profits, instead of paying them out in the form of dividends, offers an important, simple low-cost source of finance, although this method may not provide enough funds, for example, if the firm is seeking to grow.

A new issue of shares might be made in a variety of different circumstances:

- The company might want to raise more cash. If it issues ordinary shares for cash, should the shares be issued pro rata to existing shareholders, so that control or ownership of the company is not affected? If, for example, a company with 200,000 ordinary shares in issue decides to issue 50,000 new shares to raise cash, should it offer the new shares to existing shareholders, or should it sell them to new shareholders instead?

- If a company sells the new shares to existing shareholders in proportion to their existing shareholding in the company, we have a rights issue. In the example above, the 50,000 shares would be issued as a one-in-four rights issue, by offering shareholders one new share for every four shares they currently hold.

- If the number of new shares being issued is small compared to the number of shares already in issue, it might be decided instead to sell them to new shareholders, since ownership of the company would only be minimally affected.

- The company might want to issue shares partly to raise cash, but more importantly to float’ its shares on a stick exchange.

- The company might issue new shares to the shareholders of another company, in order to take it over.

New shares issues

A company seeking to obtain additional equity funds may be:

- an unquoted company wishing to obtain a Stock Exchange quotation

- an unquoted company wishing to issue new shares, but without obtaining a Stock Exchange quotation

- a company which is already listed on the Stock Exchange wishing to issue additional new shares.

The methods by which an unquoted company can obtain a quotation on the stock market are:

- an offer for sale

- a prospectus issue

- a placing

- an introduction.

Offers for sale:

An offer for sale is a means of selling the shares of a company to the public.

- An unquoted company may issue shares, and then sell them on the Stock Exchange, to raise cash for the company. All the shares in the company, not just the new ones, would then become marketable.

- Shareholders in an unquoted company may sell some of their existing shares to the general public. When this occurs, the company is not raising any new funds, but just providing a wider market for its existing shares (all of which would become marketable), and giving existing shareholders the chance to cash in some or all of their investment in their company.

When companies ‘go public’ for the first time, a ‘large’ issue will probably take the form of an offer for sale. A smaller issue is more likely to be a placing, since the amount to be raised can be obtained more cheaply if the issuing house or other sponsoring firm approaches selected institutional investors privately.

Rights issues

A rights issue provides a way of raising new share capital by means of an offer to existing shareholders, inviting them to subscribe cash for new shares in proportion to their existing holdings.

For example, a rights issue on a one-for-four basis at 280c per share would mean that a company is inviting its existing shareholders to subscribe for one new share for every four shares they hold, at a price of 280c per new share.

A company making a rights issue must set a price which is low enough to secure the acceptance of shareholders, who are being asked to provide extra funds, but not too low, so as to avoid excessive dilution of the earnings per share.

Preference shares

Preference shares have a fixed percentage dividend before any dividend is paid to the ordinary shareholders. As with ordinary shares a preference dividend can only be paid if sufficient distributable profits are available, although with ‘cumulative’ preference shares the right to an unpaid dividend is carried forward to later years. The arrears of dividend on cumulative preference shares must be paid before any dividend is paid to the ordinary shareholders.

From the company’s point of view, preference shares are advantageous in that:

- Dividends do not have to be paid in a year in which profits are poor, while this is not the case with interest payments on long term debt (loans or debentures).

- Since they do not carry voting rights, preference shares avoid diluting the control of existing shareholders while an issue of equity shares would not.

- Unless they are redeemable, issuing preference shares will lower the company’s gearing. Redeemable preference shares are normally treated as debt when gearing is calculated.

- The issue of preference shares does not restrict the company’s borrowing power, at least in the sense that preference share capital is not secured against assets in the business.

- The non-payment of dividend does not give the preference shareholders the right to appoint a receiver, a right which is normally given to debenture holders.

However, dividend payments on preference shares are not tax deductible in the way that interest payments on debt are. Furthermore, for preference shares to be attractive to investors, the level of payment needs to be higher than for interest on debt to compensate for the additional risks.

For the investor, preference shares are less attractive than loan stock because:

- they cannot be secured on the company’s assets

- the dividend yield traditionally offered on preference dividends has been much too low to provide an attractive investment compared with the interest yields on loan stock in view of the additional risk involved.

Loan stock

Loan stock is long-term debt capital raised by a company for which interest is paid, usually half yearly and at a fixed rate. Holders of loan stock are therefore long-term creditors of the company.

Loan stock has a nominal value, which is the debt owed by the company, and interest is paid at a stated “coupon yield” on this amount. For example, if a company issues 10% loan stocky the coupon yield will be 10% of the nominal value of the stock, so that $100 of stock will receive $10 interest each year. The rate quoted is the gross rate, before tax.

Debentures are a form of loan stock, legally defined as the written acknowledgement of a debt incurred by a company, normally containing provisions about the payment of interest and the eventual repayment of capital.

Debentures with a floating rate of interest

These are debentures for which the coupon rate of interest can be changed by the issuer, in accordance with changes in market rates of interest. They may be attractive to both lenders and borrowers when interest rates are volatile.

Security

Loan stock and debentures will often be secured. Security may take the form of either a fixed charge or a floating charge.

- Fixed charge; Security would be related to a specific asset or group of assets, typically land and buildings. The company would be unable to dispose of the asset without providing a substitute asset for security, or without the lender’s consent.

- Floating charge; With a floating charge on certain assets of the company (for example, stocks and debtors), the lender’s security in the event of a default payment is whatever assets of the appropriate class the company then owns (provided that another lender does not have a prior charge on the assets). The company would be able, however, to dispose of its assets as it chose until a default took place. In the event of a default, the lender would probably appoint a receiver to run the company rather than lay claim to a particular asset.

The redemption of loan stock

Loan stock and debentures are usually redeemable. They are issued for a term of ten years or more, and perhaps 25 to 30 years. At the end of this period, they will “mature” and become redeemable (at par or possibly at a value above par).

Most redeemable stocks have an earliest and latest redemption date. For example, 18% Debenture Stock 2007/09 is redeemable, at any time between the earliest specified date (in 2007) and the latest date (in 2009). The issuing company can choose the date. The decision by a company when to redeem a debt will depend on:

- how much cash is available to the company to repay the debt

- the nominal rate of interest on the debt. If the debentures pay 18% nominal interest and the current rate of interest is lower, say 10%, the company may try to raise a new loan at 10% to redeem the debt which costs 18%. On the other hand, if current interest rates are 20%, the company is unlikely to redeem the debt until the latest date possible, because the debentures would be a cheap source of funds.

There is no guarantee that a company will be able to raise a new loan to pay off a maturing debt, and one item to look for in a company’s balance sheet is the redemption date of current loans, to establish how much new finance is likely to be needed by the company, and when.

Mortgages are a specific type of secured loan. Companies place the title deeds of freehold or long leasehold property as security with an insurance company or mortgage broker and receive cash on loan, usually repayable over a specified period. Most organisations owning property which is unencumbered by any charge should be able to obtain a mortgage up to two thirds of the value of the property.

As far as companies are concerned, debt capital is a potentially attractive source of finance because interest charges reduce the profits chargeable to corporation tax.

Retained earnings

For any company, the amount of earnings retained within the business has a direct impact on the amount of dividends. Profit re-invested as retained earnings is profit that could have been paid as a dividend. The major reasons for using retained earnings to finance new investments, rather than to pay higher dividends and then raise new equity for the new investments, are as follows:

- The management of many companies believes that retained earnings are funds which do not cost anything, although this is not true. However, it is true that the use of retained earnings as a source of funds does not lead to a payment of cash.

- The dividend policy of the company is in practice determined by the directors. From their standpoint, retained earnings are an attractive source of finance because investment projects can be undertaken without involving either the shareholders or any outsiders.

- The use of retained earnings as opposed to new shares or debentures avoids issue costs.

- The use of retained earnings avoids the possibility of a change in control resulting from an issue of new shares.

Another factor that may be of importance is the financial and taxation position of the company’s shareholders. If, for example, because of taxation considerations, they would rather make a capital profit (which will only be taxed when shares are sold) than receive current income, then finance through retained earnings would be preferred to other methods.

A company must restrict its self-financing through retained profits because shareholders should be paid a reasonable dividend, in line with realistic expectations, even if the directors would rather keep the funds for re-investing. At the same time, a company that is looking for extra funds will not be expected by investors (such as banks) to pay generous dividends, nor over-generous salaries to owner-directors.

Bank lending

Borrowings from banks are an important source of finance to companies. Bank lending is still mainly short term, although medium-term lending is quite common these days.

Short term lending may be in the form of:

- an overdraft, which a company should keep within a limit set by the bank. Interest is charged (at a variable rate) on the amount by which the company is overdrawn from day to day;

- a short-term loan, for up to three years.

Medium-term loans are loans for a period of from three to ten years. The rate of interest charged on medium-term bank lending to large companies will be a set margin, with the size of the margin depending on the credit standing and riskiness of the borrower. A loan may have a fixed rate of interest or a variable interest rate, so that the rate of interest charged will be adjusted every three, six, nine or twelve months in line with recent movements in the Base Lending Rate.

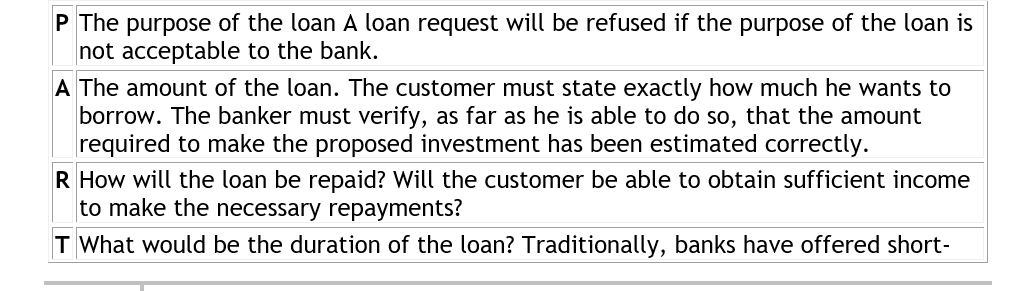

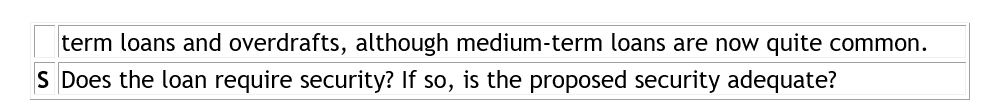

Lending to smaller companies will be at a margin above the bank’s base rate and at either a variable or fixed rate of interest. Lending on overdraft is always at a variable rate. A loan at a variable rate of interest is sometimes referred to as a floating rate loan. Longer-term bank loans will sometimes be available, usually for the purchase of property, where the loan takes the form of a mortgage. When a banker is asked by a business customer for a loan or overdraft facility, he will consider several factors, known commonly by the mnemonic PARTS.

Purpose

Amount

Repayment

Term

Security

Leasing

A lease is an agreement between two parties, the “lessor” and the “lessee”. The lessor owns a capital asset, but allows the lessee to use it. The lessee makes payments under the terms of the lease to the lessor, for a specified period of time.

Leasing is, therefore, a form of rental. Leased assets have usually been plant and machinery, cars and commercial vehicles, but might also be computers and office equipment. There are two basic forms of lease: “operating leases” and “finance leases”.

Operating leases

Operating leases are rental agreements between the lessor and the lessee whereby:

- the lessor supplies the equipment to the lessee

- the lessor is responsible for servicing and maintaining the leased equipment

- he period of the lease is fairly short, less than the economic life of the asset, so that at the end of the lease agreement, the lessor can either

- lease the equipment to someone else, and obtain a good rent for it, or sell the equipment secondhand.

Finance leases

Finance leases are lease agreements between the user of the leased asset (the lessee) and a provider of finance (the lessor) for most, or all, of the asset’s expected useful life.

Suppose that a company decides to obtain a company car and finance the acquisition by means of a finance lease. A car dealer will supply the car. A finance house will agree to act as lessor in a finance leasing arrangement, and so will purchase the car from the dealer and lease it to the company. The company will take possession of the car from the car dealer, and make regular payments (monthly, quarterly, six monthly or annually) to the finance house under the terms of the lease.

Other important characteristics of a finance lease:

- The lessee is responsible for the upkeep, servicing and maintenance of the asset. The lessor is not involved in this at all.

- The lease has a primary period, which covers all or most of the economic life of the asset. At the end of the lease, the lessor would not be able to lease the asset to someone else, as the asset would be worn out. The lessor must, therefore, ensure that the lease payments during the primary period pay for the full cost of the asset as well as providing the lessor with a suitable return on his investment.

- It is usual at the end of the primary lease period to allow the lessee to continue to lease the asset for an indefinite secondary period, in return for a very low nominal rent. Alternatively, the lessee might be allowed to sell the asset on the lessor’s behalf (since the lessor is the owner) and to keep most of the sale proceeds, paying only a small percentage (perhaps 10%) to the lessor.

Why might leasing be popular

The attractions of leases to the supplier of the equipment, the lessee and the lessor are as follows:

The supplier of the equipment is paid in full at the beginning. The equipment is sold to the lessor, and apart from obligations under guarantees or warranties, the supplier has no further financial concern about the asset.

The lessor invests finance by purchasing assets from suppliers and makes a return out of the lease payments from the lessee. Provided that a lessor can find lessees willing to pay the amounts he wants to make his return, the lessor can make good profits. He will also get capital allowances on his purchase of the equipment.

Leasing might be attractive to the lessee:

- if the lessee does not have enough cash to pay for the asset, and would have difficulty obtaining a bank loan to buy it, and so has to rent it in one way or another if he is to have the use of it at all; or

- if finance leasing is cheaper than a bank loan. The cost of payments under a loan might exceed the cost of a lease.

Operating leases have further advantages:

- The leased equipment does not need to be shown in the lessee’s published balance sheet, and so the lessee’s balance sheet shows no increase in its gearing ratio.

- The equipment is leased for a shorter period than its expected useful life. In the case of high-technology equipment, if the equipment becomes out-of-date before the end of its expected life, the lessee does not have to keep on using it, and it is the lessor who must bear the risk of having to sell obsolete equipment secondhand.

The lessee will be able to deduct the lease payments in computing his taxable profits.

Hire purchase

Hire purchase is a form of instalment credit. Hire purchase is similar to leasing, with the exception that ownership of the goods passes to the hire purchase customer on payment of the final credit instalment, whereas a lessee never becomes the owner of the goods.

Hire purchase agreements usually involve a finance house.

- The supplier sells the goods to the finance house.

- The supplier delivers the goods to the customer who will eventually purchase them.

- The hire purchase arrangement exists between the finance house and the customer.

The finance house will always insist that the hirer should pay a deposit towards the purchase price. The size of the deposit will depend on the finance company’s policy and its assessment of the hirer. This is in contrast to a finance lease, where the lessee might not be required to make any large initial payment.

An industrial or commercial business can use hire purchase as a source of finance. With industrial hire purchase, a business customer obtains hire purchase finance from a finance house in order to purchase the fixed asset. Goods bought by businesses on hire purchase include company vehicles, plant and machinery, office equipment and farming machinery.

Government assistance

The government provides finance to companies in cash grants and other forms of direct assistance, as part of its policy of helping to develop the national economy, especially in high technology industries and in areas of high unemployment. For example, the Indigenous Business Development Corporation of Zimbabwe (IBDC) was set up by the government to assist small indigenous businesses in that country.

Venture capital

Venture capital is money put into an enterprise which may all be lost if the enterprise fails. A businessman starting up a new business will invest venture capital of his own, but he will probably need extra funding from a source other than his own pocket. However, the term ‘venture capital’ is more specifically associated with putting money, usually in return for an equity stake, into a new business, a management buy-out or a major expansion scheme.

The institution that puts in the money recognises the gamble inherent in the funding. There is a serious risk of losing the entire investment, and it might take a long time before any profits and returns materialise. But there is also the prospect of very high profits and a substantial return on the investment. A venture capitalist will require a high expected rate of return on investments, to compensate for the high risk.

A venture capital organisation will not want to retain its investment in a business indefinitely, and when it considers putting money into a business venture, it will also consider its “exit”, that is, how it will be able to pull out of the business eventually (after five to seven years, say) and realise its profits. Examples of venture capital organisations are: Merchant Bank of Central Africa Ltd and Anglo American Corporation Services Ltd.

When a company’s directors look for help from a venture capital institution, they must recognise that:

- the institution will want an equity stake in the company

- it will need convincing that the company can be successful

- it may want to have a representative appointed to the company’s board, to look after its interests.

The directors of the company must then contact venture capital organisations, to try and find one or more which would be willing to offer finance. A venture capital organisation will only give funds to a company that it believes can succeed, and before it will make any definite offer, it will want from the company management:

- a business plan

- details of how much finance is needed and how it will be used

- the most recent trading figures of the company, a balance sheet, a cash flow forecast and a profit forecast

- details of the management team, with evidence of a wide range of management skills

- details of major shareholders

- details of the company’s current banking arrangements and any other sources of finance

- any sales literature or publicity material that the company has issued.

A high percentage of requests for venture capital are rejected on an initial screening, and only a small percentage of all requests survive both this screening and further investigation and result in actual investments.

Franchising

Franchising is a method of expanding business on less capital than would otherwise be needed. For suitable businesses, it is an alternative to raising extra capital for growth. Franchisors include Budget Rent-a-Car, Wimpy, Nando’s Chicken and Chicken Inn.

Under a franchising arrangement, a franchisee pays a franchisor for the right to operate a local business, under the franchisor’s trade name. The franchisor must bear certain costs (possibly for architect’s work, establishment costs, legal costs, marketing costs and the cost of other support services) and will charge the franchisee an initial franchise fee to cover set-up costs, relying on the subsequent regular payments by the franchisee for an operating profit. These regular payments will usually be a percentage of the franchisee’s turnover.

Although the franchisor will probably pay a large part of the initial investment cost of a franchisee’s outlet, the franchisee will be expected to contribute a share of the investment himself. The franchisor may well help the franchisee to obtain loan capital to provide his-share of the investment cost.

The advantages of franchises to the franchisor are as follows:

- The capital outlay needed to expand the business is reduced substantially.

- The image of the business is improved because the franchisees will be motivated to achieve good results and will have the authority to take whatever action they think fit to improve the results.

The advantage of a franchise to a franchisee is that he obtains ownership of a business for an agreed number of years (including stock and premises, although premises might be leased from the franchisor) together with the backing of a large organisation’s marketing effort and experience. The franchisee is able to avoid some of the mistakes of many small businesses, because the franchisor has already learned from its own past mistakes and developed a scheme that works.