GOVERNMENT SECTOR FINANCIAL REPORTING

An International Perspective

In recent decades, accounting has become increasingly global. The trend towards globalisation began with the development of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRSs) in the private sector. However this has in more recent times been replicated in the public sector with the development of International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSASs). However it would be true to say that for a variety of reasons global convergence on accounting standards is closer in the private rather than the public sectors, and even in the former there are still major challenges to be overcome if full convergence is to take place in the near future.

Traditionally, government accounting and financial reporting around the world has been based on cash accounting rather than an accruals-based approach as has been in use in most private sector organisations for decades. There are several reasons for this. One of the major ones is that governments themselves have been driven by cash. Government revenues such as from taxation, customs duties etc. are forecast for the year ahead and matched to forecast expenditure. There may often be a deficit, depending on the state of the national economy, and if this is the case then governments will seek to borrow money to make up the difference (or failing this will have to cut government expenditure and services or raise taxes).

These revenues and expenditure forecasts are factored into the detailed budget-setting process. Budgets have traditionally been for a year ahead only, though more recently the development of Medium Term Expenditure Frameworks (MTEFs) for a three-year period or longer have helped to introduce longer planning horizons into the process. However, the general economic approach which lies around the development of national budgets is driven more by cash and what is available to spend than accounting concepts such as an accrualsbased approach.

Cash is also simpler to understand. It is after all what is available in the bank, in petty cash and in other forms of cash and cash equivalents. There are no complicating factors to understand – especially for non-accountants. There is no depreciation to worry about, no revaluation of assets, no understanding of what is meant by equity capital and other forms of capital required. There is also limited judgement involved. As soon as factors such as depreciation are introduced then we are into discussions on various methods, useful economic lives etc. and rather than having one clear answer to an accounting problem we have a range of them depending on the approach used. Cash on the other hand is was it is.

Governments and politicians it would be fair to say like clear answers to questions. They and other users can more easily understand cash accounting rather than accruals accounting. However the use of cash accounting can lead to inefficient and ineffective use of funds. A common problem in many countries is that, towards the end of the year, all unspent budgets are hastily spent, sometimes in a frantic attempt to ‘use’ unspent funds rather than ‘lose’ them by returning them to central government coffers.

But what is often disguised in the process is the sometimes-large volumes of unpaid creditors, which can sometimes be so large that organisations can be virtually insolvent and it will not be obvious until it is almost too late to address the underlying problem. This can even happen at a national level; for example, in recent times the large levels of government borrowing in Greece have only become apparent when repayment of major loans is looming. We are all aware of the difficulties this has caused for the Eurozone and the wider international economy.

In order to address these conceptual weaknesses of the traditional cash accounting approach, the International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB) was established to create global public sector accounting standards. The long-term aim of this is to encourage all public sector bodies to embrace the accruals-based IPSASs – in June 2012, there were 32 of these in existence. However this is very much a long-term project. Few countries have embraced accruals-based accounting for their public sector.

Some have though. New Zealand was a trend-setter in this respect and the United Kingdom introduced the Resource Accounting and Budgeting (RAB) project in the late 1990s; this included amongst other things accruals-based accounting. Interestingly neither adopted IPSASs. Instead they have adapted the IFRSs for the public sector.

This might seem strange but the reasoning behind this was that IPSASs were not developed enough to adopt at the time that these countries made their accounting changes. However a major project in 2010 updated the IPSASs and made them more contemporary in their information.

Government Accounting and Reporting – The Range of Possibilities

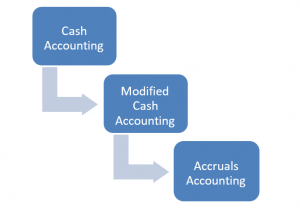

In fact, three different possibilities are possible with regards to government accounting. These simplistically summarised are as follows:

In the diagram above, these possibilities are quite deliberately shown sequentially. Moving to accruals-based accounting in the public sector is a long-term aspiration. Accounting for noncurrent assets alone is a huge undertaking and this is recognised by the fact that IPSAS 17 on Property, Plant and Equipment allows for a 5-year transition before being adopted once a country decides to move to accruals-based accounting approach for the public sector.

However, it is considered unrealistic to move from cash to accruals-based accounting in one go. There is a vast amount of information that needs to be collected, not just on non-current assets but also on a host of other areas, such as payables and receivables, bad debts, capital, leases etc. In order to prepare for this, countries will normally start to collect information to help them prepare for the move before actually fully adopting accruals accounting. This interim stage is called modified cash accounting.

The move to accruals-accounting in the public sector is likely to take a number of years to complete; for example the Republic of Georgia has declared it will move to accruals-based accounting over a ten-year period. The IPSASB has issued guidance on cash accounting and modified accruals accounting in Volume 2 of its annual publication of the IPSASs. We will now see how this has been applied to Rwanda specifically.

The Rwandan Context

Rwanda has currently adopted a modified cash accounting approach to its public sector financial reporting. The legal basis for this approach is to be found in Article 2 (20) of Ministerial Order N. 002/07 dated 9 February 2007 which relates to Financial Regulations and states that the modified cash basis should be used “using appropriate accounting policies supported by reasonable and prudent judgements and estimates”.

More important legal background is given in the Organic Law No. 37/2006 on State Finances and Property. This requires (Article 70) the submission of annual reports from all budget agencies which include all revenues collected and received during the fiscal year and all expenditures made during the same period. It also requires a statement of all outstanding receipts and payments which are known at the end of the fiscal year.

Responsibility for maintaining the accounts and records rests with the Chief Budget Manager (stipulated by Article 21 of the aforementioned Organic Law and Article 9 and 11 of the aforementioned Ministerial Order). He/she is also responsible for preparing reports on budget execution, managing revenues and expenditures, preparing, maintaining and coordinating the use of financial plans, managing the financial resources for the budget agency effectively, efficiently and transparently, ensuring sound internal control systems in the budget agency and safeguarding public property held by it.

This very clear statement of accountability is vital. It means that the Budget Manager is clear that, although they may delegate responsibility for individual accounting tasks, they cannot delegate accountability. The result of this onerous but necessary accountability should be that they take their task very seriously indeed.

The Chief Budget Manager also signs a Statement of Management’s Responsibilities which forms part of the Financial Statements. This states that “in the opinion of the Chief Budget Manager, the financial statements give a true and fair view of the state of the financial affairs of X”. It also states publicly that they are responsible for the maintenance of accounting records that can be relied upon in the preparation of financial statements, ensuring adequate systems of internal financial control and safeguarding the assets of the budget agency. An example of the Statement is shown below:

PROFORMA STATEMENT OF RESPONSIBILITIES

Article 70 of the Organic Law N° 37/2006 of 12/09/2006 on State Finances and Property requires budget agencies to submit annual reports which include all revenues collected or received and all expenditures made during the fiscal year, as well as a statement of all outstanding receipts and payments before the end of the fiscal year.

Article 21 of the Organic Law N° 37/2006 and Article 9 and Article 11 of Ministerial Order N°002/07 of 9 February 2007 further stipulates that the Chief Budget Manager is responsible for maintaining accounts and records of the budget agency, preparing reports on budget execution, managing revenues and expenditures, preparing, maintaining and coordinating the use of financial plans, managing the financial resources for the budget agency effectively, efficiently and transparently, ensuring sound internal control systems in the budget agency and safeguarding the public property held by the budget agency.

The Chief Budget Manager accepts responsibility for the annual financial statements, which have been prepared using the “modified cash basis” of accounting as defined by Article 2 (20) of the Ministerial Order N°002/07 of 9 February 2007 relating to Financial Regulations and using appropriate accounting policies supported by reasonable and prudent judgements and estimates.

These financial statements have been extracted from the accounting records of XXX and the information provided is accurate and complete in all material respects. The financial statements also form part of the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Rwanda.

In the opinion of the Chief Budget Manager, the financial statements give a true and fair view of the state of the financial affairs of XXX. The Chief Budget Manager further accepts responsibility for the maintenance of accounting records that may be relied upon in the preparation of financial statements, ensuring adequate systems of internal financial control and safeguarding the assets of the budget agency.

Signature: ______________________________________________

Name: _________________________________________________

[Chief Budget Manager]

Date:__________________________________________

Contents of the Financial Statements

General rules

An important Note always included in the financial statements is that on the Basis of Accounting. This will tell the reader the detailed approaches that have been used in the accounting. As well as confirming that modified cash accounting has been used, it will typically include statements along the following lines:

- That generally all transactions are recognised only at the time that the associated cash flows take place.

- That expenditure on the acquisition of non-current assets is not capitalised. There is no depreciation and the total cost of acquiring the assets involved is effectively written-off when payment is made.

- That all pre-paid expenditure and advances are written-off in the period of disbursement.

It will also normally detail how the ‘modification’ to this cash-based accounting is performed. This will be as follows:

- Invoices for goods and services which are outstanding at the reporting date are recognised as liabilities for that specific year.

- Loans and advances will be recognised as assets or liabilities at the time of disbursement and interest on them recognised only when disbursement is made.

- Any balances denominated in foreign currency are converted into Rwandan Francs at the rates in force at that date. Any associated exchange losses are reported as recurrent expenditure whilst any gains are dealt with as recurrent revenue.

Based on these principles the key financial statements are shown below.

Statement of Revenue and Expenditure

This Statement, as the title suggests, presents information on revenue and expenditure for the entity. The broad outline is shown in the following sample:

Other Information

Notes

We have already mentioned that key items should receive more detailed analysis by way of Notes to the Financial Statements. Students should note that the primary purpose of Financial Statements is disclosure which is associated with key concepts such as transparency and understandability. Notes should therefore not be seen as incidental to the Financial Statements and accordingly less important than the individual Statements we have discussed above. They are instead integral and fundamental to the Financial Statements as a whole (the IPSASs guidance is specific on this point but it is also common sense as users need more information to fully understand the financial situation).

What should be specifically included in the Notes depends on the individual entity. Proper judgement should be used – the preparers of financial statements should put themselves in the position of users who do not have the access to detailed organisational knowledge that they do. However, as we have already seen the Note on the Basis of Accounting is vital in all financial statements. Other areas which will often be presented include:

- The Presentation Currency, which will nearly always be Rwandan Francs.

- Narrative explanation of contents of revenue and numerical analysis of key contents. Transfers from Treasury will often be listed individually with the dates that the transfer was made and the amount involved.

- Narrative description of Expenditure sub-headings and appropriate additional numerical disclosure of the values involved.

- Narrative description of items in the Statement of Financial Position such as cash (which includes Cash Equivalents), Receivables and Payables.

Details of any Foreign Exchange conversions made.

Budget Execution Report

Also included with the Financial Statements should be a Budget Execution Report. This lists out major categories in Income and Expenditure and the resultant Surplus or Deficit and gives a Budgeted amount for each category. Alongside this, presented in columnar format, Actual amounts should be entered and a resultant Variance calculated.

Dates that the Financial Statements are adopted

Finalising the Financial Statements is normally an iterative process as adjustments may emerge as a result of extra information being obtained after the Reporting Date or items requiring correction may emerge during the audit. Therefore it should be clearly stated in a prominent position when the Financial Statements are formally adopted.

Audit

The Office of the Auditor General (OAG) will be responsible for auditing the draft Financial Statements and the Auditor General will express an opinion on whether or not they give a true and fair view of the state of financial affairs of the entity.

ACCOUNTING FOR CONSIGNMENTS

Background to consignments

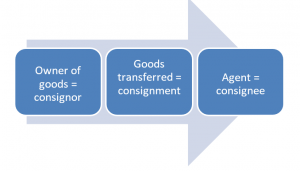

Sometimes a business may not have its own retail premises but may instead choose to undertake its business through an agent. In such situations, the business sending the goods is said to be a consignor and the agent acting on their behalf is a consignee. The goods sent are said to be delivered on a consignment basis.

Accounting implications of consignment

The consignee will then sell the goods on behalf of the consignor, and normally retain an element of the proceeds as a commission. They may also incur costs on behalf of the consignor (e.g. shipping costs, storage costs), and depending on the specific conditions attaching to the arrangement, can then deduct these costs from the proceeds before transferring the net amount to the consignor. They will also have to account for these transactions with what is effectively a receipts and payments account for the items involved.

It should be noted that legal ownership of the goods rests with the consignor until the goods are sold. Any stock which remains unsold at the Reporting Date should be included in the inventory figures for the consignor and not the consignee.

Bookkeeping in the records of the consignor

Three accounts are needed in the records of the consignor. These are;

- The Consignment Account: this is basically the profit and loss account for the consignment transaction. Income received from selling the goods will be recorded here and any expenses will be offset against it. The balance is obviously the profit or loss on the transaction and will be transferred to the Statement of Consolidated Income.

- The Consignee account: this is the debtor or creditor account for the consignee. This will show either any monies that the consignee is due to pay over to the consignor or vice-versa. The former situation is more likely, especially if the consignee deducts their costs from the proceeds before paying the net amount over to the consignor.

- The Consignment Inventory account: these are where all movements of stock are recorded. When items are transferred from ‘normal’ inventory to that despatched on consignment then the double entry will be to credit the ‘normal’ inventory and debit ‘consignment inventory’.

Arrangements will need to be made for regular stock-checks on the consignee’s premises, especially around the Reporting Date. Any agreement should clearly specify who is to be responsible for any losses in inventory due to misplacing them, theft or damage. It should also be clear who is responsible for insuring the items involved. Any bad debts however would normally be the responsibility of the consignor. However in some cases a special (del credere) commission may be paid to the consignee, in which case they will be responsible for accounting for the bad debt and picking up any corresponding loss.

At the end of the period, the unsold consignment inventory value should be carried forward to the next accounting period in the books of the consignor as in any other form of inventory. However, in line with the accounting rules on inventory (IAS 2 in the private sector, IPSAS 12 is the public sector accruals-based equivalent) all costs incurred in bringing that inventory to its present location and condition can be included in the valuation of inventory including consignee’s expenses, provided that the over-arching rule about inventory being shown as the lower of cost or Net Realisable Value (NRV) is complied with. Note however that marketing costs incurred by the consignee cannot be included.

Bookkeeping in the records of the consignee

To some extent, these are a mirror image of the consignor’s accounting entries. However it should be noted that the consignor will not have an inventory account, as the stocks do not belong to them. The account heads required are therefore merely a consignor account, which records the proceeds collected by the consignee on behalf of the consignor, net of any expenses that the consignee is permitted to deduct such as commission and other direct costs of sale. Any commission received will be credited to the appropriate account heading in the general ledger and will be included in the year-end Financial Statements as part of the Statement of Comprehensive Income in the same way as any other item of revenue. Similarly, any costs which are not reimbursed – for example any bad debts that the consignee is responsible for – will be debited to the appropriate expense head.

ACCOUNTING FOR BANKS Banks

It is often the case that banks in particular will have very well-prepared financial statements, though the absolute quality may depend to some extent on the context. Especially if a bank is part of a large, multi-national organisation there will be strong internal pressure to ensure that financial information is prudently prepared and that it is consistent (especially important as financial information will usually have to be consolidated into multi-national financial statements and any inconsistencies or errors could therefore have a serious impact).

There are also sound organisational reasons why banking tends to have high quality financial statements, in many countries providing best practice in financial statements. The financial statements for one thing are especially important and investors and other stakeholders will want reassurance that the bank in question is organised on a sound financial footing; a situation of course that has become more obviously important in the past few years with the serious financial problems that have faced many banks.

Banks also tend to be able to attract top quality accounting staff through the relative attractiveness of salaries and other benefits that they are able to offer. They are also, if they are part of a multinational banking group, likely to be subject to strong internal audit reviews from the banks that they are part of. They will also be subject to a greater degree of external regulation than many other bodies. All of these reasons tend to drive up the quality of financial statements in banks – though the recent problems faced globally by the industry suggest that even here there is in some instances much room for improvement.

Banks in Rwanda and accounting regulation

Banks are subject to IFRS accounting rules in Rwanda. Reviews of the banking sector in the World Bank Report on the Observance of Standards and Codes (ROSC) Report of 2008 stated that the market in Rwanda engaged in the main in traditional banking activities such as lending and deposits and foreign exchange transactions. This perhaps means that the market has been limited in terms of its risk exposure compared to some other nations where for example complex financial instruments like derivatives are much more widely used.

The National Bank of Rwanda (BNR) regulates financial reporting by banks and non-bank financial institutions and issues accounting instructions governing the treatment of specific transactions—e.g. provisions for non-performing loans. In the exercise of powers conferred to it by its statutes, the Banking Act, and other legal provisions, the National Bank of Rwanda is empowered to enact regulations, issue instructions, and take decisions that banks, insurance companies, and other financial institutions must comply with if they wish to do business.

The accounting and auditing requirements, as outlined in the Banking Act, are in addition to those set by the Companies Act. The National Bank of Rwanda requires these institutions to designate at least one external auditor chosen from a list that it prepares on a regular basis. External auditors of banks are required to follow the generally prevailing standards of their profession coupled with the regulations, instructions, and decisions of the Central Bank. The term of an auditor’s mandate is three years, renewable only once.

Compliance with IFRS requirements is a pre-requisite for banks. However, there are additional financial requirements that the banks are required to meet. The ROSC Report noted that the banking and financial institutions were the only ones to have an accounting and reporting framework in Rwanda in 2008 but were not fully in compliance with IFRS in practice. The Report found that “most banks’ accounting treatment for investments in treasury bills and long-term government stocks does not comply with determination of impairment, specifically in relation to the impairment of loans and advances, under IAS 39.

Capital Adequacy Ratios

Banks are in a different financial position than most other institutions as they are holding large sums of money on behalf of others and they may be required to repay money to investors at short notice. Furthermore there is a very close and immediate connection between the health of banks and the health of the economy as a whole. A serious failure in a bank can have serious, and sometimes disastrous, repercussions for the global economy. The failure of the American investment bank Lehman Brothers in 2008 had a major impact, not just on the US economy but on that of the world as a whole. Ongoing challenges for European banks affected by the ‘Euro crisis’ continue to create major pressures on the wider economy of that region.

For this reason, banks in Rwanda, along with many other countries, are required to maintain prudent ratios of capital funds to ensure that they can meet repayment demands and by so doing maintain confidence in the economy and amongst investors. Such regulations are called ‘prudential’ requirements and the BNR Department of Banking Supervision is responsible for monitoring compliance with these requirements.

. INSURANCE COMPANIES

There are no specific legal regulations applying to insurance companies. However they are required to once more comply with IFRS requirements in their accounting and reporting practices. The BNR Department of Supervision of Non-Banking Institutions is responsible for monitoring compliance with IFRS. However the ROSC Review found that the insurance sector was not, in 2008, meeting IFRS requirements..

. LIQUIDATION & BANKRUPTCIES

Definition:

In law, liquidation is the process by which a company (or part of a company) is brought to an end, and the assets and property of the company redistributed. Liquidation is also sometimes referred to as winding up or dissolution, although dissolution technically refers to the last stage of liquidation.

Liquidation may either be compulsory (Creditors’ Liquidation) or voluntary (Shareholders’ Liquidation)

The liquidator will normally have a duty to ascertain whether any misconduct has been conducted by those in control of the company which has caused prejudice to the general body of creditors. In some legal systems, the liquidator may be able to bring an action against errant directors or shadow directors for either wrongful trading or fraudulent trading.

The liquidator must determine the company’s title to property to enforce their claims against the assets of the company to the extent that they are subject to a valid security interest. In most legal systems, only fixed security takes precedence over all claims, security by way of floating charge may be postponed to the preferential creditors.

Priority of Claims on the company’s assets will be determined in the following order:-

- Liquidators Costs

- Creditors with fixed charge over assets

- Costs incurred by an administrator

- Amounts owing to employees for wages/superannuation

- Payments owing in respect of workers injuries

- Amounts owing to employees for leave

- Retrenchment payments owing to employees

- Creditors with floating charge over assets

- Creditors with security over assets

- Shareholders

Having wound up the company’s affairs, the liquidator must call a final meeting of the members, creditors or both. The liquidator is then usually required to send final accounts to the Registrar and to notify the court. The company is then dissolved.

In Rwanda please refer to website: Codes of Laws of Rwanda, Law no 08/2002 of 05/02/2002 relating to Regulations Governing Banks and other Financial Institutions.

Liquidation of Banks or Financial Institutions in Rwanda

Any bank or financial institution under liquidation must:-

- Inscribe after the company’s name, the words – IN LIQUIDATION and not act as a bank or a financial institution except with a clear mention that it is under liquidation

- Immediately stop its operations except those strictly necessary for its liquidation

- Put up in all its premises open to the public, a notice showing its being under liquidation either with the mention, of the Central Bank’s authorization or the Court’s judgement depending on the case

The Central bank will supervise the bank or financial institution during the liquidation process. The Central Bank receives copies of all documents and letters relating to liquidation. The legal status of the bank or financial institution under liquidation remains unaltered till its closure.

In every liquidation of a bank or financial institution the realization of all assets’ and any eventual guarantees (Article 53 paragraph 2), minus expenses linked to the liquidation shall be distributed to the various categories of creditors as follows:-

- Guarantee holders up to the value of their guarantees

- Depositors

- The State

- Other Certified Creditors

The Court may authorize the liquidator to affix seals on properties of administrators and managers whose responsibility seems to be involved in accordance with Article 65.

It may also authorize the liquidator to:-

- Seize and freeze or make restrictions on monies due to the persons as well as on movable or fixed assets belonging to them;

- Make objections in such forms and effects as are allowed by the Civil Law to those same persons exercising their rights to dispose of any fixed assets

Forced liquidation is pronounced by Court after distribution of the remainder and approval of the liquidator’s accounts.

Bankruptcies

Bankruptcy is a legal status of an insolvent person or an organisation, that is, one who cannot repay the debts they owe to creditors. In most jurisdictions bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debtor.

Bankruptcy is not the only legal status that an insolvent person or organisation may have, and the term bankruptcy is therefore not the same as insolvency. In some countries, including the United Kingdom, bankruptcy is limited to individuals, and other forms of insolvency proceedings, for example, liquidation and administration are applied to companies. In the United States the term bankruptcy is applied more broadly to formal insolvency proceedings.

Bankruptcy prevents a person’s creditors from obtaining a judgment against them. With a judgment a creditor can attempt to garnish wages or seize certain types of property. However, if a debtor has no wages (because they are unemployed or retired) and has no property, they are “judgment proof”, meaning a judgment would have no impact on their financial situation. Creditors typically do not initiate legal action against a debtor with no assets, because it’s unlikely they could collect the judgment.

If enough time passes, seven years in most jurisdictions, the debt is removed from the debtor’s credit history.

A debtor with no assets or income cannot be garnished by a creditor, and therefore the “Take No Action” approach may be the correct option, particularly if the debtor does not expect to have a steady income or property a creditor could attempt to seize.

. IPSAS

Presentation of Financial Statements – IPSAS 1

IPSAS 1 (“Presentation of Financial Statements”) gives general guidance as to the types of financial statements to be prepared in the public sector (along with IPSAS 2 on the cash flow statement). It is drawn primarily from IAS 1. It should be applied to all general purpose financial statements prepared and presented under the accrual basis of accounting in accordance with IPSASs. In common with most IPSASs, it applies to all public sector entities other than Government Business Enterprises which use IFRSs for their financial reporting.

It outlines that there are six basic components of financial statements namely a Statement of Financial Position, a Statement of Financial Performance, a statement of changes in net assets/equity, a cash flow statement, a comparison of budget and actual amounts (only if the budget is made publicly available) and the notes to the financial statements. It is important to emphasise that the disclosures in the notes are considered a fundamental part of the financial statements – but detailed guidelines on what should go into the notes for specific elements of the financial statements are found in individual IPSASs on the topics involved and not in IPSAS 1, which sets out high level contents only.

Many of these financial statements are similar to those in use within the private sector. One important difference however is the comparison of budget and actual amounts. This reflects the fact that in the public sector the budget has a greater and different significance than it does in the private sector. In particular it is a tool to help ensure accountability of those responsible for the control of resources and their effective, efficient and economic use. IPSAS 1 does not give detailed guidance on the budget v actual comparison statement which is covered in more detail within IPSAS 24, “Presentation of Budget Information in Financial Statements” (this is one of the few IPSASs for which there is no equivalent IFRS).

Entities are encouraged to present other information than that included in the financial statements to assist users in assessing the performance of the entity, its stewardship of assets and making an informed evaluation about decisions on the allocation of resources. Such information might include performance indicators, statements of service performance, program reviews and other reports by management. These areas will be further covered in the “Conceptual Framework” which is currently being prepared by IFAC to provide a framework within which future IPSASs will be prepared and current IPSASs possibly revised.

IPSAS 1 states that financial statements shall present fairly the financial position, financial performance, and cash flows of an entity. Fair presentation requires the faithful representation of the effects of transactions, other events, and conditions in accordance with the definitions and recognition criteria for assets, liabilities, revenue, and expenses set out in IPSASs. The application of IPSASs, with additional disclosures when necessary, is presumed to result in financial statements that achieve a fair presentation.

An entity whose financial statements comply with IPSASs shall make an explicit and unreserved statement of such compliance in the notes. Financial statements shall not be described as complying with IPSASs unless they comply with all the requirements of IPSASs – in other words selective application of IPSASs is not permitted.

In addition to the over-arching consideration of ‘fair presentation’ other important concepts are included, for example;

- that the financial statements are prepared on the basis that the entity is a ‘going concern’

- that there is in normal circumstances consistency of presentation from one reporting period to the next

- the concept of materiality and aggregation of large numbers of transactions into classes for reporting purposes

- that the offsetting of assets and liabilities, or revenue and expenses, is not permitted unless specifically allowed or required by an IPSAS

- that comparative information for previous periods will be included in the financial statements unless an IPSAS allows or requires its non-inclusion (e.g. in the first reporting period for a new entity)

Much of the detailed guidance in IPSAS 1 replicates that found in IAS 1 and is therefore not replicated here. The main differences between the two are shown below:

- Commentary additional to that in IAS 1 has been included in IPSAS 1 to clarify the applicability of the Standard to accounting by public sector entities, e.g., discussion on the application of the going concern concept has been expanded.

- IAS 1 allows the presentation of either a statement showing all changes in net assets/equity, or a statement showing changes in net assets/equity, other than those arising from capital transactions with owners and distributions to owners in their capacity as owners. IPSAS 1 requires the presentation of a statement showing all changes in net assets/equity.

- IPSAS 1 uses different terminology, in certain instances, from IAS 1. The most significant examples are the use of the terms “statement of financial performance,” and “net assets/equity” in IPSAS 1. The equivalent terms in IAS 1 are “income statement,” and “equity”.

- IPSAS 1 does not use the term “income,” which in IAS 1 has a broader meaning than the term “revenue.”

- IPSAS 1 contains commentary on timeliness of financial statements, because of the lack of an equivalent Framework in IPSASs (paragraph 69). However this may be revised once the Conceptual Framework is finalised.

- IPSAS 1 contains an authoritative summary of qualitative characteristics (based on the IASB framework) in Appendix A. Again, this may be revised once the Conceptual Framework is finalised.

Cash Flow Statements – IPSAS 2

IPSAS 2 is drawn primarily from International Accounting Standard (IAS) 7, Cash Flow Statements. You should note that although cash flow statements are discussed in detail in IPSAS 2, IPSAS 1 on the presentation of financial statements also makes reference to them.

In practice, there are no significant differences between IPSAS 2 and IAS 7. However there are some differences in the detail, namely:

- Commentary additional to that in IAS 7 has been included in IPSAS 2 to clarify the applicability of the standards to accounting by public sector entities. IPSAS 2 uses different terminology, in certain instances, from IAS 7. The most significant examples are the use of the terms “revenue,” “statement of financial performance,” and “net assets/equity” in IPSAS 2. The equivalent terms in IAS 7 are “income,” “income statement,” and “equity.”

- IPSAS 2 contains a different set of definitions of technical terms from IAS 7 (paragraph

- In common with IAS 7, IPSAS 2 allows either the direct or indirect method to be used to present cash flows from operating activities. Where the direct method is used to present cash flows from operating activities, IPSAS 2 encourages disclosure of a reconciliation of surplus or deficit to operating cash flows in the notes to the financial statements (paragraph 29).

Inventories – IPSAS 12

IPSAS 12 (“Inventories”) is drawn substantially from IAS 2. As the name suggests, its objective is to prescribe the accounting treatment for inventories. Specifically it provides guidance on the calculation of cost and the subsequent recognition of inventories as expenses when they are consumed or sold. They also provide guidance on the write-down of inventories to their Net Realisable Value (in the case of inventories held for re-sale, defined as the future sales proceeds of any inventory less any future costs that would be incurred to make that sale happen).

Inventories in the public sector may take a number of different forms, some of them quite unusual. These include:

- Ammunition

- Consumable stores

- Maintenance materials

- Energy reserves

- Stocks of unissued currency

The cost of inventories shall comprise all costs of purchase, costs of conversion, and other costs incurred in bringing the inventories to their present location and condition. Costs of purchase includes any non-reclaimable taxes and import duties. If there are any conversion costs, such as would be the case with a publicly-owned manufacturing environment which takes raw materials and turns them into finished goods then any attributable overheads may also be added to the cost as long as these overhead costs are allocated in a systematic fashion.

The accounting treatment in IPSAS 12 is similar to that in IAS 2. Basically, when inventories are sold, exchanged, or distributed, the carrying amount of those inventories shall be recognized as an expense in the period in which the related revenue is recognized. If there is no related revenue, the expense is recognized when the goods are distributed or the related service is rendered.

There are only a few differences between IPSAS 12 and IAS 2. IPSAS 12 requires that where inventories are provided at no charge or for a nominal charge, they are to be valued at the lower of cost and current replacement cost (in the public sector it is not as unusual for inventories to move from one organisation to another on a free-of-charge basis as it is in the private sector). In addition the financial statement known as the ‘Statement of Financial Performance’ is known as the ‘Income Statement’ in IAS 2, which also uses the term ‘income’ rather than ‘revenue’.

Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors – IPSAS 3

IPSAS 3 (“Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors”) is drawn from IAS 8. The objective of this Standard is to prescribe the criteria for selecting and changing accounting policies, together with the (a) accounting treatment and disclosure of changes in accounting policies, (b) changes in accounting estimates, and (c) the corrections of errors. This Standard is intended to enhance the relevance and reliability of an entity’s financial statements, and the comparability of those financial statements over time and with the financial statements of other entities.

In the public, as in the private, sector an entity has some discretion as to the accounting policies it adopts to most fairly represent the financial transactions of the business. Therefore it is important that there is some guidance laid out to ensure that there is an appropriate methodology for the adoption of accounting policies and also around how they are changed. Equally, mistakes will from time to time be made in the preparation of financial statements and they may not always be picked up in the audit subsequently. Therefore guidance is also required to ensure that if errors are not discovered until after the financial statements have been formally approved then there are appropriate measures adopted to react to the situation.

It should be noted that one of the allowable reasons for changing an accounting policy is the publication of a new IPSAS. Entities will always have a transition period during which they may move from the existing accounting treatment to that which is required by the new IPSAS. On the other hand the management of the entity may feel that a different policy is required because of changes that have taken place within the entity itself. Changes of accounting policy, which usually require restatement of comparative figures and opening balances should not be confused with changes in accounting estimate, which do not.

Estimates may often be used in government accounting for example estimated amounts of tax revenues, estimated bad debt provisions for uncollected debts or the obsolescence of inventory. When these estimates turn out to be in need of correction – and remember that an estimate is almost certain to be incorrect to some extent because the outcome is uncertain. These estimates should be corrected in the current financial period and not previous ones.

Errors can arise in respect of the recognition, measurement, presentation, or disclosure of elements of financial statements. Financial statements do not comply with IPSASs if they contain either material errors, or immaterial errors made intentionally to achieve a particular presentation of an entity’s financial position, financial performance, or cash flows. Nevertheless some financial statements may inadvertently contain material errors which are not picked up. If they do and the financial statements have not yet been finalised then the drafts of these should of course be collected before publication. However if they are only picked up once the financial statements are approved then the correct accounting treatment is to adjust the comparative figures in the next year’s financial statements and adjust the opening balances accordingly.

Once more the major differences between IPSAS 3 and IAS 8 mainly revolve around terminology. IPSAS 3 uses the terms ‘Statement of Financial Performance’, accumulated surplus or deficit and net assets/equity whereas in IAS 8 these are termed ‘income statement’, ‘retained earnings’ and ‘equity’. Also IPSAS 3 talks of ‘revenue’, which is called ‘income’ in IAS 8. In addition, unlike IAS 8 IPSAS 3 does not require disclosures about earnings per share, which are not normally relevant in a public sector context.

Events after the reporting date – IPSAS 14

IPSAS 14, “Events after the reporting date”, is drawn from IAS 10, “Events after the balance sheet date”. Its objective is to prescribe;

- When an entity should adjust its financial statements for events after the reporting date; and

- The disclosures that an entity should give about the date when the financial statements were authorized for issue, and about events after the reporting date.

It also requires that an entity should not prepare its financial statements on a going concern basis if events subsequent to the reporting date mean that this is not appropriate.

Events after the reporting date may be analysed into adjusting and non-adjusting in nature. Adjusting events occur when information is received after the reporting date which gives more evidence about a condition that already existed at the reporting date. One example would be when a court case has been commenced against the entity where, say, a provision of 30,000,000 RwF has been established. If the court case is decided after the reporting date but before the financial statements are organised and the court finds that the entity is liable to make payments of 40,000,000 RwF then the financial statements should be adjusted accordingly.

Non-adjusting events are those which occur after the reporting date and, although significant, do not normally give evidence of a condition existing at the balance sheet date. Examples given by IPSAS 14 include a major fire after the reporting date that destroys a substantial asset, a major acquisition or disposal, changes in tax rates or tax laws, large falls in asset values or big foreign exchange losses. These non-adjusting events do not require the financial statements to be re-stated but they should be disclosed in the notes to the financial statements if they are material.

There are no major differences in principle between IPSAS 14 and IAS 10, although some extra guidance is given in the former to explain better how it applies to the private sector. Other than that the differences are once more largely in terminology.

Property , Plant and Equipment – IPSAS 17

IPSAS 17 (“Property, Plant and Equipment”) is drawn primarily from IAS 16, which has the same name. It provides one of the major challenges when public sector accounting moves from a cash to an accruals basis for the first time. It is often a major exercise to assemble all the information required to accurately state an entity’s Property, Plant and Equipment (PPE) values for the first time. It is also necessary to establish policies on depreciation, that is allocating the cost of the asset over the period in which it is expected to have a useful life and amortisation, which is effectively a write-down that must be made when an asset suffers a permanent diminution in value.

The objective of IPSAS 17 is to prescribe the accounting treatment for property, plant, and equipment so that users of financial statements can discern information about an entity’s investment in this and the changes in such investment. The principal issues in accounting for property, plant, and equipment are (a) the recognition of the assets, (b) the determination of their carrying amounts (a carrying amount is the value that the asset has in the Statement of Financial Position), and (c) the depreciation charges and impairment losses to be recognized in relation to them.

The Standard applies to all assets (except some which are specifically dealt with by other IPSAS) including some that are quite specific to the public sector such as specialist military equipment and infrastructure assets (these would be for example roads or bridges). It does not however apply to mining activities when mineral reserves such as oil or gas are depleted by uses. It does not apply either to biological assets (these include animals kept for resale or slaughter or crops grown for harvesting) which are dealt with by IPSAS 27. Other IPSAS also deal with assets in specific situations, such as IPSAS 16, which deals with properties held for investment purposes, or IPSAS 13 on leased assets.

An in private sector accounting, the general rules are that the cost of an item of property, plant, and equipment shall be recognized as an asset if, and only if:

- It is probable that future economic benefits or service potential associated with the item will flow to the entity; and

- The cost or fair value of the item can be measured reliably (fair value is the price at which the property could be exchanged between knowledgeable, willing parties in an arm’s length transaction).

The cost of an item of property, plant, and equipment comprises:

- Its purchase price, including import duties and non-refundable purchase taxes, after deducting trade discounts and rebates.

- Any costs directly attributable to bringing the asset to the location and condition necessary for it to be capable of operating in the manner intended by management.

- The initial estimate of the costs of dismantling and removing the item and restoring the site on which it is located, the obligation for which an entity incurs either when the item is acquired, or as a consequence of having used the item during a particular period for purposes other than to produce inventories during that period.

Only directly attributable costs may be capitalised as part of the asset value. IPSAS 17 says that these include:

- The costs of employee benefits (as defined in the relevant international or national accounting standard dealing with employee benefits – the IPSAS dealing with this is IPSAS 25) arising directly from the construction or acquisition of the item of property, plant, and equipment;

- Costs of site preparation;

- Initial delivery and handling costs;

- Installation and assembly costs;

- Costs of testing whether the asset is functioning properly, after deducting the net proceeds from selling any items produced while bringing the asset to that location and condition (such as samples produced when testing equipment); and

- Professional fees.

An important element of IPSAS 17 is that entities that are making the transition to accruals accounting based on IPSAS for the first time have a five-year period to make that transition as far as the recognition of plant, property and equipment under this particular Standard is concerned.

Further, an entity that adopts accrual accounting for the first time in accordance with IPSASs shall initially recognize property, plant, and equipment at cost or fair value. For items of property, plant, and equipment that were acquired at no cost, or for a nominal cost, cost is the item’s fair value as at the date of acquisition (this might be the case if for example an asset was gifted as part of a legacy or was transferred at no cost from another government department).

In such situations, the entity shall recognize the effect of the initial recognition of property, plant, and equipment as an adjustment to the opening balance of accumulated surpluses or deficits for the period in which the property, plant, and equipment is initially recognized.

Although IPSAS 17 is drawn primarily from IAS 16, Property, Plant and Equipment, as amended by IAS 16 (part of the Improvements to IFRSs which was issued in May 2008) there are some differences between the private and public sector versions of the Standard. As one detailed example, at the time of issuing IPSAS 17, the IPSASB has not yet considered the applicability of IFRS 5, Non-current Assets Held for Sale andDiscontinued Operations to public sector entities; therefore, IPSAS 17 does not reflect amendments made to IAS 16 consequent upon the issue of IFRS 5.

However, the main differences between IPSAS 17 and IAS 16 (2003) are as follows:

- IPSAS 17 does not require or prohibit the recognition of heritage assets. An entity that recognizes heritage assets is required to comply with the disclosure requirements of this Standard with respect to those heritage assets that have been recognized and may, but is not required to, comply with other requirements of this Standard in respect of those heritage assets. IAS 16 does not have a similar exclusion. (A heritage asset is one which has particular historic or cultural significance, such as a Parliament building or an archaeological site which makes the use of conventional asset valuation rules of limited relevance)

- IAS 16 requires items of property, plant, and equipment to be initially measured at cost. IPSAS 17 states that where an item is acquired at no cost, or for a nominal cost, its cost is its fair value as at the date it is acquired.

- IAS 16 requires, where an enterprise adopts the revaluation model and carries items of property, plant, and equipment at revalued amounts, the equivalent historical cost amounts should be disclosed. This requirement is not included in IPSAS 17.

- Under IAS 16, revaluation increases and decreases may only be matched on an individual item basis. Under IPSAS 17, revaluation increases and decreases are offset on a class of asset basis (this could make a significant difference).

- IPSAS 17 contains transitional provisions for both the first time adoption and changeover from the previous version of IPSAS 17. IAS 16 only contains transitional provisions for entities that have already used IFRSs. Specifically, IPSAS 17 contains transitional provisions allowing entities to not recognize property, plant, and equipment for reporting periods beginning on a date within five years following the date of first adoption of accrual accounting in accordance with IPSASs. The transitional provisions also allow entities to recognize property, plant, and equipment at fair value on first adopting this Standard. IAS 16 does not include these transitional provisions. This is an important concession in that it can sometimes be very difficult to assemble all the necessary data to allow the transition to an accruals-based approach to asset accounting and it allows public sector entities a significant amount of time to do so.

- IPSAS 17 contains definitions of “impairment loss of a non-cash-generating asset” and “recoverable service amount.” IAS 16 does not contain these definitions. This is an important distinction. A non-cash generating asset is one that is not held for the generation of a commercial return and there are a number of these in use in the public sector which would not be the case in the private sector.

- IPSAS 17 uses different terminology, in certain instances, from IAS 16. The most significant examples are the use of the terms “statement of financial performance,” and “net assets/equity” in IPSAS 17. The equivalent terms in IAS 16 are “income statement” and “equity.” IPSAS 17 does not use the term “income,” which in IAS 16 has a broader meaning than the term “revenue.”

- IC SECTOR

Intangible Assets – IPSAS 31

This is one of the most recent IPSASs to be created and is based on International Accounting Standard (IAS) 38, Intangible Assets published by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). It also contains extracts from the Standing Interpretations Committee Interpretation 32 (SIC 32), Intangible Assets—Web Site Costs. It includes useful application guidance on how to deal with website costs and has a number of illustrative examples which show how accounting for intangible assets could be applied in various situations such as when a patent, copyright or license is acquired from a public sector entity.

The main differences between IPSAS 31 and IAS 38 are as follows:

- IPSAS 31 incorporates the guidance contained in the Standing Interpretation Committee’s Interpretation 32, Intangible Assets—Web Site Costs as Application Guidance to illustrate the relevant accounting principles.

- IPSAS 31 does not require or prohibit the recognition of intangible heritage assets (as is also the case with tangible assets dealt with by IPSAS 17). An entity that recognizes intangible heritage assets is required to comply with the disclosure requirements of this Standard with respect to those intangible heritage assets that have been recognized and may, but is not required to, comply with other requirements of this Standard in respect of those intangible heritage assets. IAS 38 does not have similar guidance.

- IAS 38 contains requirements and guidance on goodwill and intangible assets acquired in a business combination. IPSAS 31 does not include this guidance.

- IAS 38 contains guidance on intangible assets acquired by way of a government grant. Paragraphs 50–51 of IPSAS 31 modify this guidance to refer to intangible assets acquired through non-exchange transactions. IPSAS 31 states that where an intangible asset is acquired through a non-exchange transaction, the cost is its fair value as at the date it is acquired.

- IAS 38 provides guidance on exchanges of assets when an exchange transaction lacks commercial substance. IPSAS 31 does not include this guidance.

- The examples included in IAS 38 have been modified to better address public sector circumstances.

- IPSAS 31 uses different terminology, in certain instances, from IAS 38. The most significant examples are the use of the terms “revenue,” “statement of financial performance,” “surplus or deficit,” “future economic benefits or service potential,” “accumulated surpluses or deficits,” “operating/operation,” “rights from binding arrangements (including rights from contracts or other legal rights),” and “net assets/equity” in IPSAS 31. The equivalent terms in IAS 38 are “income,” “statement of comprehensive income,” “profit or loss,” “future economic benefits,” “retained earnings,” “business,” “contractual or other legal rights,” and “equity.”

Investment Property – IPSAS 16

IPSAS 16 is drawn primarily from International Accounting Standard (IAS) 40 (Revised 2003), Investment Property. In common with some other IPSASs, there are some transitional arrangements that apply when an entity adopts accrual accounting for the first time in accordance with IPSASs. These state that in such circumstances the entity shall initially recognize investment property at cost or fair value. For investment properties that were acquired at no cost, or for a nominal cost, cost is the investment property’s fair value as at the date of acquisition. The entity should recognize the effect of the initial recognition of investment property as an adjustment to the opening balance of accumulated surpluses or deficits for the period in which accrual accounting is first adopted in accordance with IPSASs.

In terms of the comparison of IPSAS 16 to IAS 40 (2003), Investment Property, the IPSAS notes that the IPSASB has not yet considered the applicability of IFRS 4, Insurance Contracts, and IFRS 5, Non-current Assets Held for Sale and Discontinued Operations, to public sector entities; therefore IPSAS 16 does not reflect amendments made to IAS 40 consequent upon the issue of those IFRSs.

The other main differences between IPSAS 16 and IAS 40 are as follows:

- IPSAS 16 requires that investment property initially be measured at cost and specifies that where an asset is acquired for no cost or for a nominal cost, its cost is its fair value as at the date of acquisition. IAS 40 requires investment property to be initially measured at cost.

- There is additional commentary to make clear that IPSAS 16 does not apply to property held to deliver a social service that also generates cash inflows. Such property is accounted for in accordance with IPSAS 17, Property, Plant, and Equipment.

- IPSAS 16 contains transitional provisions for both the first time adoption and changeover from the previous version of IPSAS 16. IAS 40 only contains transitional provisions for entities that have already used IFRSs.

- IFRS 1 deals with first time adoption of IFRSs. IPSAS 16 includes additional transitional provisions that specify that when an entity adopts the accrual basis of accounting for the first time and recognizes investment property that was previously unrecognized, the adjustment should be reported in the opening balance of accumulated surpluses or deficits.

- Commentary additional to that in IAS 40 has been included in IPSAS 16 to clarify the applicability of the standards to accounting by public sector entities.

- IPSAS 16 uses different terminology, in certain instances, from IAS 40. The most significant example is the use of the term “statement of financial performance” in IPSAS 16. The equivalent term in IAS 40 is “income statement.” In addition, IPSAS 16 does not use the term “income,” which in IAS 40 has a broader meaning than the term “revenue.”

Provisions, Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets – IPSAS 19

This International Public Sector Accounting Standard (IPSAS) is drawn primarily from International Accounting Standard (IAS) 37 (1998), Provisions, Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets. It includes guidance on what action should be taken when transitioning to using IPSAS 19 for the first time, namely that the effect of adopting this Standard shall be reported as an adjustment to the opening balance of accumulated surpluses/(deficits) for the period in which the Standard is first adopted. Entities are encouraged, but not required, to (a) adjust the opening balance of accumulated surpluses/(deficits) for the earliest period presented, and (b) to restate comparative information. If comparative information is not restated, this fact shall be disclosed.

There are some differences between IPSAS 19 and IAS 37 as follows:

- IPSAS 19 includes commentary additional to that in IAS 37 to clarify the applicability of the standards to accounting by public sector entities. In particular, the scope of IPSAS 19 clarifies that it does not apply to provisions and contingent liabilities arising from social benefits provided by an entity for which it does not receive consideration that is approximately equal to the value of the goods and services provided directly in return from recipients of those benefits (this is to take account of the fact that public sector entities often provide goods or services that are “free at the point of delivery” to the end user or at least provided in return for consideration that is below normal market values). However, if the entity elects to recognize provisions for social benefits, IPSAS 19 requires certain disclosures in this respect.

- The scope paragraph in IPSAS 19 makes it clear that while provisions, contingent liabilities, and contingent assets arising from employee benefits are excluded from the scope of the Standard, the Standard, however, applies to provisions, contingent liabilities, and contingent assets arising from termination benefits that result from a restructuring dealt with in the Standard.

- IPSAS 19 uses different terminology, in certain instances, from IAS 37. The most significant examples are the use of the terms “revenue” and “statement of financial performance” in IPSAS 19. The equivalent terms in IAS 37 are “income” and “income statement.”

- The Implementation Guidance included in IPSAS 19 has been amended to be more reflective of the public sector.

- IPSAS 19 contains an Illustrated Example that illustrates the journal entries for recognition of the change in the value of a provision over time, due to the impact of the discount factor (the discount factor measures the way that time affects the value of money and is built into the calculations of long-term provisions).

Accounting for revenues in the public sector (IPSASs 9 and 23)

There are two IPSASs in particular that focus on accounting for revenues in the public sector. IPSAS 9 deals with accounting for what is known as exchange transactions and IPSAS 23 deals with accounting for non-exchange transactions, especially taxes and transfers. As IPSAS 23 has no IFRS equivalent it will be necessary to discuss this in more detail than some other IPSASs.

What is the difference between exchange and a non-exchange transactions?

Exchange transactions are transactions in which one entity receives assets or services, or has liabilities extinguished, and directly gives approximately equal value (primarily in the form of cash, goods, services, or use of assets) to another entity in exchange. This might be thought of as being equivalent to a commercial transactions which explains why this IPSAS is based on an IFRS (IAS 18, Revenue). So when, for example, a public sector provides goods and/or services for which it receives in return a payment that is related to their market value then it should apply IPSAS 9 in its accounting treatment.

If on the other hand there is no exchange of approximately equal value then IPSAS 23 will apply – such transactions will be described as ‘non-exchange’ in nature. This will be the case for many public sector transactions. For example when governments raise taxation revenues, there is no direct correlation between them and consequent expenditures. Although the taxpayer will rightly expect ‘value’ from their tax contributions, it is not normally possible to directly match their individual contributions to say expenditures on health, education, defence or many other public services.

IPSAS 9 – Exchange Transactions

As already mentioned these have a similar nature to commercial transactions and are therefore based on IAS 18. IPSAS 9 reminds us that revenue is recognised when it is probable that future economic benefits or service potential will flow to the entity and when such benefits can be measured reliably.

There are no significant variations between IPSAS 9 and IAS 18, with the differences in detail being as follows:

- The title of IPSAS 9 differs from that of IAS 18, and this difference clarifies that IPSAS 9 does not deal with revenue from non-exchange transactions.

- The definition of “revenue” adopted in IPSAS 9 is similar to the definition adopted in IAS 18. The main difference is that the definition in IAS 18 refers to ordinary activities (IPSAS 9 makes no such distinction).

- Commentary additional to that in IAS 18 has also been included in IPSAS 9 to clarify the applicability of the standards to accounting by public sector entities.

- IPSAS 9 uses different terminology, in certain instances, from IAS 18. The most significant example is the use of the term “net assets/equity” in IPSAS 9. The equivalent term in IAS 18 is “equity.”

IPSAS 23 – Non-Exchange Transactions

The introduction to IPSAS 23 notes that the majority of government revenues is generated in the form of taxes and transfers but that, until the passing of the Standard, there was no specific guidance in how to deal with transactions involving such items.

In summary, IPSAS 23:

- Takes a transactional analysis approach whereby entities are required to analyse inflows of resources from non-exchange transactions to determine if they meet the definition of an asset and the criteria for recognition as an asset, and if they do, determine whether a liability is also required to be recognized;

- Requires that assets recognized as a result of a non-exchange transaction initially be measured at their fair value as at the date of acquisition;

- Requires that liabilities recognized as a result of a non-exchange transaction be recognized in accordance with the principles established in IPSAS 19, Provisions,

Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets;

- Requires that revenue equal to the increase in net assets associated with an inflow of resources be recognized;

- Provides specific guidance that addresses:

- Taxes; and

- Transfers, including:

- Debt forgiveness and assumption of liabilities;

- Fines;

- Bequests;

- Gifts and Donations, including goods in-kind;

- Services in-kind;

- Permits, but does not require, the recognition of services in-kind; and

- Requires disclosures to be made in respect of revenue from non-exchange transactions. IP

An entity will recognize an asset arising from a non-exchange transaction when it gains control of resources that meet the definition of an asset and satisfy the recognition criteria. Contributions from owners do not give rise to revenue, so each type of transaction is analysed, and any contributions from owners are accounted for separately. Consistent with the approach set out in this Standard, entities will analyse non-exchange transactions to determine which elements of general purpose financial statements will be recognized as a result of the transactions.

Two kinds of revenue transaction are relevant within the framework of IPSAS 23. The first is when an asset comes under the control of an entity without an approximately equivalent exchange taking place in return. This would be the case when for example an asset is transferred to an organisation free of charge (or, if there is a charge, it is significantly below market value). In such circumstances a simple yes/no decision tree needs to be followed which is illustrated below.

Simplistically summarised, the flowchart shows that in certain circumstances when a nonexchange transaction takes place then it creates both an asset and also revenue. For example, if an entity were given an asset for which they paid nothing but its market value was worth 5,000,000 RWF then the double entry for this would be to create an asset of 5,000,000 RwF and to recognise revenue (as a credit entry) also of 5,000,000 RwF. However, if the entity incurs a liability for that asset which is below its market value then the revenue should be reduced to the extent of that liability.

Revenue from taxes

The general rule is that an entity shall recognize an asset in respect of taxes when the taxable event occurs and the asset recognition criteria are met. The definition of an asset is met when the entity controls the resources as a result of a past event (the taxable event) and expects to receive future economic benefits or service potential from those resources. In addition, it must be probable that the inflow of resources will occur and that their fair value can be reliably measured.

Taxation revenue arises only for the government that imposes the tax, and not for other entities. For example, where the Rwandan government imposes a tax that is collected by the RRA, assets and revenue accrue to the government, not the taxation agency which is effectively acting as a collection agency on behalf of government.

Taxes do not satisfy the definition of contributions from owners, because the payment of taxes does not give the taxpayers a right to receive (a) distributions of future economic benefits or service potential by the entity during its life, or (b) distribution of any excess of assets over liabilities in the event of the government being wound up. Nor does the payment of taxes provide taxpayers with an ownership right in the government that can be sold, exchanged, transferred, or redeemed.

On the other hand, taxes satisfy the definition of a non-exchange transaction because the taxpayer transfers resources to the government, without receiving approximately equal value directly in exchange. While the taxpayer may benefit from a range of social policies established by the government, these are not provided directly in exchange as consideration for the payment of taxes.

Recognition of taxation revenue is based on the time at which the taxable event takes place, examples of which are when:

- Income tax is the earning of assessable income during the taxation period by the taxpayer;

- Value-added tax is the undertaking of taxable activity during the taxation period by the taxpayer;

- Goods and services tax is the purchase or sale of taxable goods and services during the taxation period;

- Customs duty is the movement of dutiable goods or services across the customs boundary;

- Property tax is the passing of the date on which the tax is levied, or the period for which the tax is levied, if the tax is levied on a periodic basis.

Other types of non-exchange revenue

Fines are economic benefits or service potential received or receivable by a public sector entity, from an individual or other entity, as determined by a court or other law enforcement body, as a consequence of the individual or other entity breaching the requirements of laws or regulations.

Fines normally require an entity to transfer a fixed amount of cash to the government, and do not impose on the government any obligations which may be recognized as a liability. As such, fines are recognized as revenue when the receivable meets the definition of an asset and satisfies the criteria for recognition as an asset which have already been discussed. Where an entity collects fines in the capacity of an agent, the fine will not be revenue of the collecting entity. Assets arising from fines are measured at the best estimate of the inflow of resources to the entity.

Sometimes a bequest may be made to a government entity. A bequest is a transfer made according to the provisions of a deceased person’s will. The past event giving rise to the control of resources embodying future economic benefits or service potential for a bequest occurs when the entity has an enforceable claim, for example on the death of the person making the bequest.

Bequests that satisfy the definition of an asset are recognized as assets and revenue when it is probable that the future economic benefits or service potential will flow to the entity, and the fair value of the assets can be measured reliably. Determining the probability of an inflow of future economic benefits or service potential may be problematic if a period of time elapses between the death of the testator and the entity receiving any assets.

The entity will need to determine if the deceased person’s estate is sufficient to meet all claims on it, and satisfy all bequests. If the will is disputed, this will also affect the probability of assets flowing to the entity. Therefore it can be seen that asset and revenue recognition is not always a straightforward situation with bequests. It is necessary to obtain an estimate of the fair value of bequeathed assets, for example by obtaining the latest market values for assets bequeathed.

Disclosures

Both IFRSs and IPSASs are as much about disclosure as they are about accounting treatment. IPSAS 23 has a list of disclosure requirements that apply specifically to non-exchange transactions. These include a requirement to disclose the following details:

- Either on the face of, or in the notes to, the general purpose financial statements:

UBLIC SECTOR

- The amount of revenue from non-exchange transactions recognized during the period by major classes showing separately:

- Taxes, showing separately major classes of taxes; and

- Transfers, showing separately major classes of transfer revenue.

- The amount of receivables recognized in respect of non-exchange revenue;

- The amount of liabilities recognized in respect of transferred assets subject to conditions

- The amount of assets recognized that are subject to restrictions and the nature of those restrictions; and

- The existence and amounts of any advance receipts in respect of non-exchange transactions.

- An entity shall disclose in the notes to the general purpose financial statements:

- The accounting policies adopted for the recognition of revenue from non-exchange transactions;

- For major classes of revenue from non-exchange transactions, the basis on which the fair value of inflowing resources was measured;

- For major classes of taxation revenue that the entity cannot measure reliably during the period in which the taxable event occurs, information about the nature of the tax; and

- The nature and type of major classes of bequests, gifts, and donations.

Borrowing Costs – IPSAS 5

IPSAS 5 is drawn primarily from IAS 23, Borrowing Costs. The Standard makes clear that borrowing may be for commercial purposes or, in the case of government entities, for social policy at a notional charge – IPSAS 5 specifically gives as an example of such an entity a government housing department.

There are no significant differences between IPSAS 5 and IAS 23. Those small differences which do exist are as follows:

- Commentary additional to that in IAS 23 has been included in IPSAS 5 to clarify the applicability of the standards to accounting by public sector entities.

- IPSAS 5 uses different terminology, in certain instances, from IAS 23. The most significant examples are the use of the terms “revenue,” “statement of financial performance,” and “net assets/equity” in IPSAS 5. The equivalent terms in IAS 23 are “income,” “income statement,” and “equity.”

- IPSAS 5 contains a different set of definitions of technical terms from IAS 23 (these are included in paragraph 5 and cover ‘borrowing costs’ and ‘qualifying asset’).

Leases – IPSAS 13

This is drawn primarily from IAS 17, Leases. Several exceptions are outlined by IPSAS 13 where other IPSASs will be applied instead. These are IPSAS 16 (Investment Properties) and IPSAS 27 (Biological Assets). Also not covered by IPSAS 13 are situations where there are leases to explore or use mineral assets, oil, etc. and licensing agreements such as those covering motion picture films, plays, patents and copyrights.

Specific mention is made of transitional arrangements that apply to leasing. Retrospective application of IPSAS 13 by entities that have already adopted the accrual basis of accounting and that intend to comply with IPSASs as they are issued is encouraged but not required.

There are no substantial differences between IPSAS 13 and IAS 17. Those differences that do exist are as follows;

- Commentary additional to that in IAS 17 has been included in IPSAS 13 to clarify the applicability of the standards to accounting by public sector entities.