Audit evidence

In order for the auditor’s opinion to be considered trustworthy, auditors must come to their conclusions having completed a thorough examination of the books and records of their clients and they must document the procedures performed and evidence obtained, to support the conclusions reached.

ISA 500 Audit Evidence states the objective of the auditor, in terms of gathering evidence, is:

‘to design and perform audit procedures in such a way to enable the auditor to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence to be able to draw reasonable conclusions on which to base the auditor’s opinion.’ [ISA 500, 4]

- Sufficiency relates to the quantity of evidence.

- Appropriateness relates to the quality or relevance and reliability of

[ISA 500, 5b, 5e]

Sufficient evidence

There needs to be ‘enough’ evidence to support the auditor’s conclusion. This is a matter of professional judgment. When determining whether there is enough evidence the auditor must consider:

- The risk of material misstatement

- The materiality of the item

- The nature of accounting and internal control systems

- The results of controls tests

- The auditor’s knowledge and experience of the business

- The size of a population being tested

- The size of the sample selected to test

- The reliability of the evidence obtained.

Sufficient evidence

Consider, for example, the audit of a bank balance:

Auditors will confirm year-end bank balances directly with the bank. This is a good source of evidence but on its own is not sufficient to give assurance regarding the completeness and final valuation of bank and cash amounts. The key reason is timing differences. The client may have received cash amounts or cheques before the end of the year, or may have paid out cheques before the end of the year, that have not yet cleared the bank account.

For this reason the auditor should also review and reperform the client’s year-end bank reconciliation.

In combination these two pieces of evidence will be sufficient to give assurance over the bank balances.

Appropriate evidence

Appropriateness of evidence breaks down into two important concepts:

- Reliability

[ISA 500, 5b]

Reliability

Auditors should always attempt to obtain evidence from the most trustworthy and dependable source possible.

- Evidence obtained from an independent external source is more reliable than client generated evidence.

- Evidence obtained directly by the auditor is more reliable than evidence obtained indirectly.

- Client generated evidence is the least reliable source of evidence. If the client is manipulating the financial statement figures they may produce fictitious evidence to support the figures. Client generated evidence is more reliable if effective controls are in place. This doesn’t mean the auditor should not rely on client generated evidence. It simply means that where more reliable evidence is available, the auditor should obtain it.

- In addition, written evidence is more reliable than oral evidence as oral representations can be withdrawn or challenged. Originals are more reliable than copies as it may be difficult to see whether copies have been tampered with.

[ISA 500, A31]

Broadly speaking, the more reliable the evidence the less of it the auditor will need. However, if evidence is unreliable it will never be appropriate for the audit, no matter how much is gathered. [ISA 500, A4]

Relevance

Relevance means the evidence relates to the financial statement assertions being tested. [ISA 500, A27]

For example, when attending an inventory count, the auditor will:

- Select a sample of items from physical inventory and trace them to inventory records to confirm the completeness of accounting records

- Select a sample of items from inventory records and trace them to physical inventories to confirm the existence of inventory assets.

Whilst the procedures are similar in nature, their purpose (and relevance) is to test different assertions regarding inventory balances.

2 Financial statements assertions

The objective of audit testing is to assist the auditor in coming to a conclusion as to whether the financial statements are free from material misstatement.

Auditors perform a range of tests on the significant classes of transaction and account balances. These tests focus on what are known as financial statements assertions:

Assertions about classes of transactions and events, and related disclosures, for the period under audit

Occurrence – the transactions and events recorded and disclosed actually occurred and pertain to the entity.

Completeness – all transactions and events that should have been recorded have been recorded, and all related disclosures that should have been included have been included.

Accuracy – amounts and other data have been recorded appropriately and related disclosures have been appropriately measured and described.

Cut-off – transactions and events have been recorded in the correct accounting period.

Classification – transactions and events have been recorded in the proper accounts.

Presentation – transactions and events are appropriately aggregated or disaggregated and clearly described, and related disclosures are relevant and understandable in the context of the applicable financial reporting framework.

[ISA 315, A129a]

Assertions about account balances and related disclosures at the period end

Existence – assets, liabilities and equity interests exist.

Rights and obligations – the entity holds or controls the rights to assets and liabilities are the obligations of the entity.

Completeness – all assets, liabilities and equity interests that should have been recorded have been recorded, and all related disclosures that should have been included have been included.

Accuracy, valuation and allocation – assets, liabilities and equity interests have been included in the financial statements at appropriate amounts and any resulting valuation or allocation adjustments have been appropriately recorded, and related disclosures have been appropriately measured and described.

Classification – assets, liabilities and equity interests have been recorded in the proper accounts.

Presentation – account balances are appropriately aggregated or disaggregated and clearly described, and related disclosures are relevant and understandable in the context of the applicable financial reporting framework.

[ISA 315, A129b]

Inventory misstatements

There are many ways inventory could be materially misstated:

- Items might not be counted and therefore not be included in the balance.

- Items delivered after the year-end could be included in this accounting period.

- Damaged or obsolete inventory might not be valued at the lower of cost and net realisable value.

- Purchase costs might not be recorded accurately.

Addressing disclosures in the audit of financial statements

Disclosures are an important part of the financial statements and seen as a way for communicating further information to users. Poor quality disclosures may obscure understanding of important matters.

Concerns have been raised about whether auditors are giving sufficient attention to disclosures during the audit. The IAASB believes that where the term financial statements is used in the ISAs it should be clarified that this is intended to include all disclosures subject to audit.

Recent changes to ISAs include:

- Emphasis on the importance of giving appropriate attention to addressing disclosures.

- Focus on matters relating to disclosures to be discussed with those charged with governance, particularly at the planning stage.

- Emphasis on the need to agree with management their responsibility to make available information relevant to disclosures, early in the audit process.

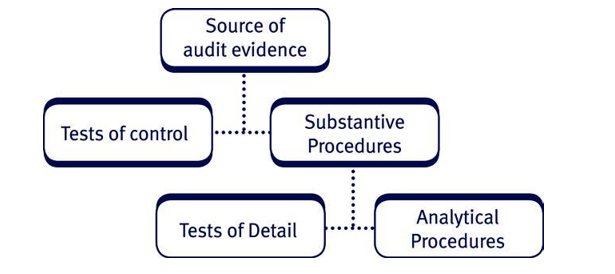

3 Sources of audit evidence

Auditors can obtain assurance from:

Tests of control: Tests of control are designed to evaluate the operating effectiveness of controls in preventing or detecting and correcting material misstatement.

Substantive procedures: Substantive procedures are designed to detect material misstatement at the assertion level.

[ISA 330, 4]

Tests of controls

In order to design further audit procedures the auditor must assess the risk of material misstatement in the financial statements.

Remember: Audit risk = Inherent risk × Control risk × Detection risk

Internal controls are a vital component of this risk model, they are the mechanisms that clients design in an attempt to prevent, detect and correct misstatement. This is not only necessary for good financial reporting, it is necessary to safeguard the assets of the shareholders and is a requirement of corporate governance.

The stronger the control system the lower the control risk and as a result, there is a lower risk of material misstatement in the financial statements.

In order to be able to rely on controls the auditor will need to:

- Ascertain how the system operates

- Document the system in audit working papers

- Test the operation of the system

- Assess the design and operating effectiveness of the control system

- Determine the impact on the audit approach for specific classes of transactions, account balances and disclosures.

The focus of a test of control is not the monetary amount of a transaction. A test of control provides evidence of whether a control procedure has operated effectively. For example, inspecting an invoice for evidence of authorisation. It is irrelevant whether the invoice is for $100 or $1000 as it the control being tested, not the amount. Therefore, it could be said that a test of control provides indirect evidence over the financial statements. The auditor makes the assumption that if controls are working effectively there is less risk of material misstatement in the financial statements. However, the test of control itself does not test the figure within the financial statements, this is the purpose of a substantive procedure.

We will learn more about the systems themselves and tests of controls in the ‘Systems and controls’.

Substantive procedures

Substantive procedures consist of:

- Tests of detail: tests of detail to verify individual transactions and

- Substantive analytical procedures: analytical procedures (as seen in the ‘Risk’) involve analysing relationships between information to identify unusual fluctuations which may indicate possible misstatement.

Tests of detail v analytical procedures

A test of detail looks at the supporting evidence for an individual transaction such as inspection of a purchase invoice to verify the amount/date/classification of a specific purchase. If there are 5000 purchase invoices recorded during the accounting period, this one test of detail has only provided evidence for one of those transactions.

An analytical procedure would be used to assess the reasonableness of the purchases figure in total. For example, calculate the percentage change in purchases from last year and then compare this with the percentage change in revenue to see if they move in line with each other as expected.

The analytical procedure is not looking at the detail of any of the individual purchases but at the total figure. It is possible that there are a number of misstatements within the purchases population which would only be discovered by testing the detail as they may cancel each other out. An analytical procedure would not detect these misstatements.

Because of this, analytical procedures should only be used as the main source of substantive evidence where the internal controls have been found to be reliable as there is less chance of misstatements being present as the control system would have detected and corrected them.

In some circumstances the auditor may rely solely on substantive testing:

- The auditor may choose to rely solely on substantive testing where it is considered to be a more efficient or more effective way of obtaining audit evidence, e.g. for smaller organisations.

- The auditor may have to rely solely on substantive testing where the client’s internal control system cannot be relied on.

The auditor must always carry out some substantive procedures on material items, and also carry out specific substantive procedures required by ISA 330 The Auditor’s Response to Assessed Risks.

The auditor is required to carry out the following substantive procedures:

- Agreeing the financial statements to the underlying accounting records.

- Examination of material journals and other adjustments made in preparing the financial statements.

[IAS 330, 20]

4 Types of audit procedure

The auditor can adopt the following procedures to obtain audit evidence:

- Inspection of records, documents or physical assets.

- Observation of processes and procedures, e.g. inventory counts.

- External confirmation obtained in the form of a direct written response to the auditor from a third party.

- Recalculation to confirm the numerical accuracy of documents or records.

- Re-performance by the auditor of procedures or controls.

- Analytical procedures.

- Enquiry of knowledgeable parties.

[ISA 500, A14 – A22]

In the ‘Procedures’ we will look in detail at how these procedures are applied to specific items in the financial statements.

Explanation of audit procedures

Inspection of documents and records: examining records or documents, in paper or electronic form.

- May give evidence of rights and obligations, e.g. title deeds.

- May give evidence that a control is operating, e.g. invoices stamped paid or authorised for payment by an appropriate signature.

- May give evidence about cut-off, e.g. the dates on invoices, despatch notes, etc.

- Confirms sales values and purchases costs.

Inspection of tangible assets: physical examination of an asset.

- To obtain evidence of existence of that asset.

- May give evidence of valuation, e.g. evidence of damage indicating impairment of inventory or non-current assets.

Observation: looking at a process or procedure being performed by others.

- May provide evidence that a control is being operated, e.g. segregation of duties or a cheque signatory.

- Only provides evidence that the control was operating properly at the time of the observation. The auditor’s presence may have had an influence on the operation of the control.

- Observation of a one-off event, e.g. an inventory count, may well give good evidence that the procedure was carried out effectively.

Enquiry: seeking information from knowledgeable persons, both financial and non-financial, within the entity or outside.

Whilst a major source of evidence, the results of enquiries will usually need to be corroborated in some way through other audit procedures. This is because responses generated by the audit client are considered to be of a low quality due to their inherent bias.

The answers to enquiries may themselves be corroborative evidence. In particular they may be used to corroborate the results of analytical procedures.

Written representations from management are part of overall enquiries. These involve obtaining written statements from management to confirm oral enquiries. These are considered further in the ‘Completion and review’.

External confirmation: obtaining a direct response (usually written) from an external, third party.

- Examples include:

– Circularisation of receivables

– Circularisation of payables where supplier statements are not available

– Confirmation of bank balances in a bank letter

– Confirmation of actual/potential penalties from legal advisers

– Confirmation of inventories held by third parties.

- May give good evidence of existence of balances, e.g. receivables confirmation.

- May not necessarily give reliable evidence of valuation,

e.g. customers may confirm receivable amounts but, ultimately, be unable to pay in the future.

Recalculation: manually or electronically checking the arithmetical accuracy of documents, records, or the client’s calculations,

e.g. recalculation of the translation of a foreign currency transaction.

Reperformance: the auditor’s independent execution of procedures or controls that were originally performed as part of the entity’s internal control system, e.g. reperformance of a bank reconciliation.

Analytical procedures: analysis of plausible relationships between data.

See below.

Analytical procedures as substantive tests

We have already come across analytical procedures as a risk procedure at the planning stage. Later in the text we will also see that they are a component of the completion of an audit. Here we consider their use as substantive procedures, i.e. procedures designed to detect material misstatement.

Analytical procedures are used to identify trends and understand relationships between sets of data. This in itself will not detect misstatement but will identify possible areas of misstatement. As such, analytical procedures cannot be used in isolation and should be coupled with other, corroborative, forms of testing, such as enquiry of management.

When performing analytical procedures, auditors do not simply look at current figures in comparison to last year. Auditors may consider other points of comparison, such as budgets and industry data.

Other techniques are also available, including:

- Ratio analysis

- Trend analysis

- Proof in total, for example: an auditor might create an expectation of payroll costs for the year by taking last year’s cost and inflating for pay rises and changes in staff numbers.

Analytical procedures are useful for assessing several assertions at once as the auditor is effectively auditing a whole account balance or class of transaction to see if it is reasonable.

They can be used to corroborate other audit evidence obtained, such as statements by management about changes in cost structures.

By using analytical procedures the auditor may identify unusual items that can then be further investigated to ensure that a misstatement doesn’t exist in the balance.

However, in order to use analytical procedures effectively the auditor needs to be able to create an expectation. It would be difficult to do this if operations changed significantly from the prior year. If the changes were planned, the auditor could use forecasts as a point of comparison, although these are inherently unreliable due to the number of estimates involved. In this circumstance it would be pointless comparing to prior years as the business would be too different to be able to conduct effective comparison.

It would also be difficult to use analytical procedures if a business had experienced a number of significant one-off events in the year as these would distort the year’s figures making comparison to both prior years and budgets meaningless.

The suitability of analytical procedures as substantive tests

The suitability of this approach depends on four factors:

- The assertion(s) under scrutiny

- The reliability of the data

- The degree of precision possible

- The amount of variation which is acceptable.

For example:

- Assertions under scrutiny

– Analytical procedures should be suitable for the assertion being tested. They are clearly unsuitable for testing the existence of inventories. They are, however, suitable for assessing the value of inventory in terms of the need for allowances against old inventories, identified using the inventory holding period ratio.

– Analytical procedures are more suitable for testing balances which are likely to be predictable over time meaning relationships between data can be analysed to identify usual fluctuations.

- Reliability of data

If controls over financial data are weak, the data is likely to contain misstatement and is therefore not suitable as a basis for assessment.

- Precision required

– As analytical procedures are a high level approach to test a balance as a whole, if the auditor needs to test with precision, analytical procedures are unlikely to identify the misstatements.

– Precision will be improved if disaggregated information is obtained and analysed. For example, when performing analytical procedures over revenue, it may produce more reliable results if sales by month/customer/product/region are analysed rather than the revenue figure as a whole.

- Acceptable variation

The amount of acceptable variation between the expected figure and the actual figure will impact whether analytical procedures provide sufficient appropriate evidence. If the level of variation from actual is higher than the level of variation the auditor is willing to accept, further procedures will be necessary to ensure the balance in the financial statements is not materially misstated.

There are two types of expert an auditor may use:

- Management’s expert – an employee of the client or someone engaged by the audit client who has expertise that is used to assist in the preparation of the financial statements.

- Auditor’s expert – an employee of the audit firm or someone engaged by the audit firm to provide sufficient appropriate evidence.

Relying on the work of a management’s expert

ISA 500 Audit Evidence provides guidance on what the auditor should consider before relying on the work of a management’s expert. This guidance is very similar to that given for relying on the work of an auditor’s expert.

The auditor must:

- Evaluate the competence, capabilities and objectivity of that expert.

- Obtain an understanding of the work of that expert.

- Evaluate the appropriateness of that expert’s work as audit evidence for the relevant assertion.

[ISA 500, 8]

The rest of this section focuses on the work of an auditor’s expert.

Relying on the work of an auditor’s expert

ISA 620 Using the Work of an Auditor’s Expert provides guidance to auditors.

If the auditor lacks the required technical knowledge to gather sufficient appropriate evidence to form an opinion, they may have to rely on the work of an expert.

Examples of such circumstances include:

- The valuation of complex financial instruments, land and buildings, works of art, jewellery and intangible assets.

- Actuarial calculations associated with insurance contracts or employee benefit plans.

- The estimation of oil and gas reserves.

- The interpretation of contracts, laws and regulations.

- The analysis of complex or unusual tax compliance issues.

[ISA 620, A1]

The auditor must determine if the expert’s work is adequate for the auditor’s purposes. [ISA 620, 5b]

To fulfil this responsibility the auditor must evaluate whether the expert has the necessary competence, capability and objectivity for the purpose of the audit. [ISA 620, 9]

Evaluating competence [ISA 620, A15]

Information regarding the competence, capability and objectivity on an expert may come from a variety of sources, including:

- Personal experience of working with the expert.

- Discussions with the expert.

- Discussions with other auditors.

- Knowledge of the expert’s qualifications, memberships of professional bodies and licences.

- Published papers or books written by the expert.

- The audit firm’s quality control procedures.

Evaluating objectivity [ISA 620, A20]

Assessing the objectivity of the expert is particularly difficult, as they may not be bound by a similar code of ethics as the auditor and, as such, may be unaware of the ethical requirements and threats with which auditors are familiar.

It may therefore be relevant to:

- Make enquiries of the client about known interests or relationships with the chosen expert.

- Discuss applicable safeguards with the expert.

- Discuss financial, business and personal interests in the client with the expert.

- Obtain written representation from the expert.

Agreeing the work [ISA 620, 11]

Once the auditor has considered the above matters they must then obtain written agreement from the expert of the following:

- The nature, scope and objectives of the expert’s work.

- The roles and responsibilities of the auditor and the expert.

- The nature, timing and extent of communication between the two parties.

- The need for the expert to observe confidentiality.

Evaluating the work [ISA 620, 12]

Once the expert’s work is complete the auditor must scrutinise it and evaluate whether it is appropriate for audit purposes.

In particular, the auditor should consider:

- The reasonableness of the findings and their consistency with other evidence.

- The significant assumptions made.

- The use and accuracy of source data.

Reference to the work of an expert

Auditors cannot devolve responsibility for forming an audit opinion. The auditor has to use their professional judgment whether the evidence produced by the expert is sufficient and appropriate to support the audit opinion.

The use of an auditor’s expert is not mentioned in an unmodified auditor’s report unless required by law or regulation. Reference to the work of an expert may be included in a modified report if it is relevant to the understanding of the modification. This does not diminish the auditor’s responsibility for the opinion. [ISA 620, 14 & 15]

Relying on internal audit

ISA 610 Using the Work of Internal Auditors provides guidance.

An internal audit department forms part of the client’s system of internal control. If this is an effective element of the control system it may reduce control risk, and therefore reduce the need for the auditor to perform detailed substantive testing.

Additionally, auditors may be able to co-operate with a client’s internal audit department and place reliance on their procedures in place of performing their own.

Before relying on the work of internal audit, the external auditor must assess the effectiveness of the internal audit function and assess whether the work produced by the internal auditor is adequate for the purpose of the audit.

Evaluating the internal audit function [ISA 610, 15]

- The extent to which the internal audit function’s organisational status and relevant policies and procedures support the objectivity of the internal auditors.

- The competence of the internal audit function.

- Whether the internal audit function applies a systematic and disciplined approach.

Evaluating objectivity [ISA 610, A7]

- Whether the internal audit function reports to those charged with governance or has direct access to those charged with governance.

- Whether the internal audit function is free from operational responsibility.

- Whether those charged with governance are responsible for employment decisions such as remuneration.

- Whether any constraints are placed on the internal function by management or those charged with governance.

- Whether the internal auditors are members of a professional body which requires compliance with ethical requirements.

Evaluating competence [ISA 610, A8]

- Whether the resources of the internal audit function are appropriate and adequate for the size of the organisation and nature of its operations.

- Whether there are established policies for hiring, training and assigning internal auditors to internal audit engagements.

- Whether internal auditors have adequate technical training and proficiency, including relevant professional qualifications and experience.

- Whether the internal auditors have the required knowledge of the entity’s financial reporting and the applicable financial reporting framework and possess the necessary skills to perform work related to the financial statements.

- Whether the internal auditors are members of a professional body which requires continued professional development.

Evaluating the systematic and disciplined approach

- Existence, adequacy and use of internal audit procedures and guidance.

- Application of quality control standards such as those in ISQC 1.

[ISA 610, A11]

If the auditor considers it appropriate to use the work of the internal auditors they then have to determine the areas and extent to which the work of the internal audit function can be used (by considering the nature and scope of work) and incorporate this into their planning to assess the impact on the nature, timing and extent of further audit procedures. [ISA 610, 17]

Evaluating the internal audit work

- The work was properly planned, performed, supervised, reviewed and documented.

- Sufficient appropriate evidence has been obtained.

- The conclusions reached are appropriate in the circumstances.

- The reports prepared are consistent with the work performed.

[ISA 610, 23]

To evaluate the work adequately, the external auditor must re-perform some of the procedures that the internal auditor has performed to ensure they reach the same conclusion. [ISA 610, 24]

The extent of the work to be performed on the internal auditor’s work will depend on the amount of judgment involved and the risk of material misstatement in that area. [ISA 610, 24]

When reviewing and re-performing some of the work of the internal auditor, the external auditor must consider whether their initial expectation of using the work of the internal auditor is still valid. [ISA 610, 25]

Note that the auditor is not required to rely on the work of internal audit. In some jurisdictions, the external auditor may be prohibited or restricted from using the work of the internal auditor by law.

Responsibility for the auditor’s opinion cannot be devolved and no reference should be made in the auditor’s report regarding the use of others during the audit.

Using the internal audit to provide direct assistance

External auditors can consider whether the internal auditor can provide direct assistance with gathering audit evidence under the supervision and review of the external auditor. ISA 610 provides guidance to aim to reduce the risk that the external auditor over uses the internal auditor.

The following considerations will be made:

- Direct assistance cannot be provided where laws and regulations prohibit such assistance, e.g. in the UK. [ISA 610, 26]

- The competence and objectivity of the internal auditor. Where threats to objectivity are present, the significance of them and whether they can be managed to an acceptable level must be considered. [ISA 610, 27]

- The external auditor must not assign work to the internal auditor which involves significant judgment, a high risk of material misstatement or with which the internal auditor has been involved. [ISA 610, 30]

- The planned work must be communicated with those charged with governance so agreement can be made that the use of the internal auditor is not excessive. [ISA 610, 31]

Where it is agreed that the internal auditor can provide direct assistance:

- Management must agree in writing that the internal auditor can provide such assistance and that they will not intervene in that work.

[ISA 610, 33a]

- The internal auditors must provide written confirmation that they will keep the external auditors information confidential. [ISA 610, 33b]

- The external auditor will provide direction, supervision and review of the internal auditor’s work. [ISA 610, 34]

- During the direction, supervision and review of the work, the external auditor should remain alert to the risk that the internal auditor is not objective or competent. [ISA 610, 35]

Documentation [ISA 610, 37]

The auditor should document:

- The evaluation of the internal auditor’s objectivity and competence.

- The basis for the decision regarding the nature and extent of the work performed by the internal auditor.

- The name of the reviewer and the extent of the review of the internal auditor’s work.

- The written agreement of management mentioned above.

- The working papers produced by the internal auditor.

Use of service organisations

Many companies use service organisations to perform business functions such as:

- Payroll processing

- Receivables collection

- Pension management.

If a company uses a service organisation this will impact the audit as audit evidence will need to be obtained from the service organisation instead of, or in addition to, the client. This needs to be taken into consideration when planning the audit.

ISA 402 Audit Considerations Relating to an Entity Using a Service Organisation provides guidance to auditors.

Planning the audit

The service organisation is an additional element to be taken into account when planning the audit and greater consideration needs to be made regarding obtaining sufficient appropriate evidence.

The auditor will need to:

- Obtain an understanding of the service organisation sufficient to identify and assess the risks of material misstatement.

- Design and perform audit procedures responsive to those risks.

[ISA 402, 1]

This requires the auditor to obtain an understanding of the service provided:

- Nature of the services and their effect on internal controls.

- Nature and materiality of the transactions to the entity.

- Level of interaction between the activities of the service organisation and the entity.

- Nature of the relationship between the service organisation and the entity including contractual terms.

[ISA 402, 9]

The auditor should determine the effect the use of a service organisation will have on their assessment of risk. The following issues should be considered:

- Reputation of the service organisation.

- Existence of external supervision.

- Extent of controls operated by service provider.

- Experience of errors and omissions.

- Degree of monitoring by the user.

Sources of information about the service organisation

- Obtaining a type 1 or type 2 report from the service organisation’s auditor. A Type 1 report provides a description of the design of the controls at the service organisation prepared by the management of the service organisation. It includes a report by the service auditor providing an opinion on the description of the system and the suitability of the controls. [ISA 402, 8bi]

A Type 2 report is a report on the description, design and operating effectiveness of controls at the service organisation. It contains a report prepared by management of the service organisation. It includes a report by the service auditor providing an opinion on the description of the system, the suitability of the controls, the effectiveness of the controls and a description of the tests of controls performed by the auditor. [para 8bii] If the auditor intends to use a report from a service auditor they should consider:

– The competence and independence of the service organisation auditor.

– The standards under which the report was issued.

- Contacting the service organisation through the client.

- Visiting the service organisation.

- Using another auditor to perform tests of controls.

[ISA 402, 12]

Responding to assessed risks

The auditor should determine whether sufficient appropriate evidence is available from the client and if not, perform further procedures or use another auditor to perform procedures on their behalf. [ISA 402, 15]

If controls are expected to operate effectively:

- Obtain a type 2 report if available and consider:

– Whether the date covered by the report is appropriate for the audit.

– Whether the client has any complementary controls in place.

– The time elapsed since the tests of controls were performed.

– Whether the tests of controls performed by the auditor are relevant to the financial statement assertions.

[ISA 402, 17]

- Perform tests of controls at the service organisation.

- Use another auditor to perform tests of controls. [ISA 402, 16]

The auditor should enquire of the client whether the service organisation has reported any frauds to them or whether they are aware of any frauds.

[ISA 402, 19]

Impact on the auditor’s report

If sufficient appropriate evidence has not been obtained, a qualified or disclaimer of opinion will be issued. [ISA 402, 20]

The use of a service organisation auditor is not mentioned in an unmodified auditor’s report unless required by law or regulation. Reference to the work of a service organisation auditor may be included in a modified report if it is relevant to the understanding of the modification. This does not diminish the auditor’s responsibility for the opinion. [ISA 402, 21]

Benefits to the audit

- Independence: because the service organisation is external to the client, the audit evidence derived from it is regarded as being more reliable than evidence generated internally by the client.

- Competence: because the service organisation is a specialist, it may be more competent in executing its role than the client’s internal department resulting in fewer errors.

- Possible reliance on the service organisation’s auditors: it may be possible for the client’s auditors to confirm information directly with the service organisation’s auditors.

Drawbacks

- The main disadvantage of outsourced services from the auditor’s point of view concerns access to records and information.

- Auditors generally have statutory rights of access to the client’s records and to receive answers and explanations that they consider necessary to enable them to form their opinion.

- They do not have such rights over records and information held by a third party such as a service organisation.

- If access to records and other information is denied by the service organisation, this may impose a limitation on the scope of the auditor’s work. If sufficient appropriate evidence is not obtained this will result in a modified auditor’s report.

6 Selecting items for testing

The auditor has 3 options for selecting items to test:

- Select all items to test (100% testing) [ISA 500, A53]

This may be chosen where the population may be very small and it is easy for the auditor to test all items. Alternatively, if it is an area over which the auditor requires greater audit confidence, for example an area that is material by nature or is considered to be of significant risk, the auditor may decide to test all items within the population.

- Selecting specific items for testing [ISA 500, A54]

Items with specific characteristics may be chosen for testing such as:

- High value items within a population

- All items over a certain amount

- Items to obtain information.

Although less than 100% of the population is being tested, this does not constitute sampling. As explained below, sampling requires all items in the population to have a chance of selection. In the categories above, only the items with the specific characteristics have a chance of selection.

- Sampling [ISA 500, A56]

The definition of sampling, as described in ISA 530 Audit Sampling is:

‘The application of audit procedures to less than 100% of items within a population of audit relevance such that all sampling units have a chance of selection in order to provide the auditor with a reasonable basis on which to draw conclusions about the entire population.’ [ISA 530, 5a]

The need for sampling

It will usually be impossible to test every item in an accounting population because of the costs involved.

It is also important to remember that auditors give reasonable not absolute assurance and therefore do not certify that the financial statements are 100% accurate.

Selecting an appropriate sample

When sampling, the auditor must choose a representative sample.

- If a sample is representative, the same conclusion will be drawn from that sample as would have been drawn had the whole population been tested.

- For a sample to be representative, it must have the same characteristics as the other items in the population from which it was chosen.

[ISA 520, A12]

- In order to reduce sampling risk and ensure the sample is representative, the auditor can increase the size of the sample selected or use stratification.

Stratification [ISA 530, Appendix 1]

Stratification is used in conjunction with sampling. Stratification is the process of breaking down a population into smaller subpopulations. Each subpopulation is a group of items (sampling units) which have similar characteristics.

The objective of stratification is to enable the auditor to reduce the variability of items within the subpopulation and therefore allow sample sizes to be reduced without increasing sampling risk.

For example the auditor may stratify the population of revenue into three subpopulations: revenue from Product A, revenue from Product B and revenue from Product C. The auditor may select a sample of revenue from Product A. The results of the testing of that sample can be extrapolated across the whole subpopulation of revenue from Product A. A sample may be selected of revenue from Product B and again, the results of that testing can be extrapolated across that subpopulation. Revenue from Product C may not be tested if it is considered immaterial.

Statistical and non-statistical sampling

Statistical sampling means any approach to sampling that uses:

- Random selection of samples, and

- Probability theory to evaluate sample results.

Any approach that does not have both these characteristics is considered to be non-statistical sampling. [ISA 530, 5g]

The approach taken is a matter of auditor judgment. [ISA 530, A9]

Statistical sampling methods

- Random selection – this can be achieved through the use of random number generators or tables.

- Systematic selection – where a constant sampling interval is used (e.g. every 50th balance) and the first item is selected randomly.

- Monetary unit selection – selecting items based upon monetary values (usually focusing on higher value items).

Non-statistical sampling methods

- Haphazard selection – auditor does not follow a structured technique but avoids bias or predictability.

- Block selection – this involves selecting a block of contiguous (i.e. next to each other) items from the population. This technique is used for cut-off testing.

[Appendix 4]

When non-statistical methods (haphazard and block) are used the auditor uses judgment to select the items to be tested. Whilst this lends itself to auditor bias it does support the risk based approach, where the auditor focuses on those areas most susceptible to material misstatement.

Designing a sample

When designing a sample the auditor has to consider:

- The purpose of the procedure

- The combination of procedures being performed

- The nature of evidence sought

- Possible misstatement conditions.

[ISA 530, A5, A6]

Illustration 1 – Murray Co sampling

Sampling

Murray Co deals with large retail customers, and therefore has a low number of large receivables balances on the receivables ledger. Given the low number of customers with a balance on Murray Co’s receivables ledger, all balances would probably be selected for testing. However, for illustrative purposes the following shows how a sample of balances would be selected using systematic and Monetary Unit Sampling.

Credit and zero balances on the receivables ledger have been removed. The number of items to be sampled has been determined as 6. The customer list has been alphabetised.

Systematic Sampling

There are 19 customers with balances in the receivables ledger. The sampling interval is calculated by taking the total number of balances and dividing it by the sample size. The sampling interval (to the nearest whole number) is therefore 3. The first item is chosen randomly, in this case item 10. Every third item after that is then also selected for testing until 6 items have been chosen.

| $000 | Customer Name | Balance | Item | Sampling |

| Customer | $ | number | Item | |

| Ref | ||||

| A001 | Anfield United Shop | 176 | 1 | |

| B002 | The Beautiful Game | 84 | 2 | |

| B003 | Beckham’s | 42 | 3 | (5) |

| C001 | Cheryl & Coleen Co | 12 | 4 | |

| D001 | Dream Team | 45 | 5 | |

| E001 | Escot Supermarket | 235 | 6 | (6) |

| G001 | Golf is Us | 211 | 7 | |

| G002 | Green Green Grass | 61 | 8 | |

| H001 | HHA Sports | 59 | 9 | |

| J001 | Jilberts | 21 | 10 | (1) |

| J002 | James Smit | 256 | 11 | |

| Partnership | ||||

| J003 | Jockeys | 419 | 12 | |

| O001 | The Oval | 92 | 13 | (2) |

| P001 | Pole Vaulters | 76 | 14 | |

| S001 | Stayrose | 97 | 15 | |

| Supermarket | ||||

| T001 | Trainers and More | 93 | 16 | (3) |

| W001 | Wanderers | 89 | 17 | |

| W003 | Walk Hike Run | 4 | 18 | |

| W004 | Winners | 31 | 19 | (4) |

Monetary Unit Sampling

Monetary Unit Sampling can utilise either the random or systematic

selection method. This example illustrates the systematic selection method.

The cumulative balance is calculated.

The sampling interval is calculated by taking the total value on the ledger of $2,103,000 (to the nearest $000) and dividing by the sample size of 6. The sampling interval is therefore $351,000.

The first item is chosen randomly (a number between 1 and 2,103,000), in this case 233. Each item after that is selected by adding the sampling interval to the last value, until six items have been selected.

| $000 | Customer Name | Balance Cumulative | Sampling | |||

| Customer | $ | Item | ||||

| Ref | ||||||

| A001 | Anfield United Shop | 176 | 176 | |||

| B002 | The Beautiful Game | 84 | 260 | (1) | $233 | |

| B003 | Beckham’s | 42 | 302 | |||

| C001 | Cheryl & Coleen Co | 12 | 314 | |||

| D001 | Dream Team | 45 | 359 | |||

| E001 | Escot Supermarket | 235 | 594 | (2) | $584 | |

| G001 | Golf is Us | 211 | 805 | |||

| G002 | Green Green Grass | 61 | 866 | |||

| H001 | HHA Sports | 59 | 925 | |||

| J001 | Jilberts | 21 | 946 | (3) | $935 | |

| J002 | James Smit | 256 | 1,202 | |||

| Partnership | ||||||

| J003 | Jockeys | 419 | 1,621 | (4) | $1,286 | |

| O001 | The Oval | 92 | 1,713 | (5) | $1,637 | |

| P001 | Pole Vaulters | 76 | 1,789 | |||

| S001 | Stayrose | 97 | 1,886 | |||

| Supermarket | ||||||

| T001 | Trainers and More | 93 | 1,979 | |||

| W001 | Wanderers | 89 | 2,068 | (6) | $1,988 | |

| W003 | Walk Hike Run | 4 | 2,072 | |||

| W004 | Winners | 31 | 2,103 | |||

Evaluating deviations and misstatements in a sample

Deviations

Any issues identified during a test of control are called deviations.

If the auditor tests a sample of 100 invoices for evidence of authorisation and 10 are found not to have been authorised, there is a deviation rate of 10%. There is no need to project this across the population as the deviation rate will still be 10%.

If the actual deviation rate exceeds the tolerable deviation rate (i.e. the rate of deviation the auditor is willing to accept), the risk of material misstatement is greater and more substantive procedures will be required.

Misstatements

Misstatements are differences between the amounts actually recorded and what should have been recorded. Misstatements are identified when performing substantive tests of detail.

The auditor must first consider the nature and cause of the misstatement. If the misstatement is an anomaly (isolated), no further procedures will be performed as the misstatement is not representative of further misstatements.

If the auditor believes the misstatement could be representative of further misstatements the auditor will project the misstatement found in the sample across the population as a whole, and evaluate the results by considering tolerable misstatement.

Tolerable misstatement is defined as:

A monetary amount set by the auditor in respect of which the auditor seeks to obtain an appropriate level of assurance that the monetary amount set by the auditor is not exceeded by the actual misstatement in the population. [ISA 530, 5e]

Tolerable misstatement is the practical application of performance materiality to an audit sample:

- If the total projected misstatement in the sample is less than tolerable misstatement then the auditor may be reasonably confident that the risk of material misstatement in the whole population is low and no further testing will be required.

- If the total projected misstatement in the sample exceeds tolerable misstatement the auditor will extend the sample in order to determine the total misstatement in the population.

Evaluating misstatements in a sample

A sample of $50,000 has been tested out of a population of $800,000. Misstatements of $2,000 were found. Tolerable misstatement has been set at $10,000.

The auditor needs to consider whether the misstatement is an anomaly and therefore isolated, or whether the misstatement is likely to be representative of further misstatements in the population.

If the misstatement is an anomaly, no further procedures will be necessary.

If it is expected that the misstatement is likely to be representative of further misstatements, the auditor should extrapolate the effect of the misstatement across the population to assess whether the projected misstatement is greater than tolerable misstatement.

Here, the auditor might expect that there are misstatements of $32,000 ($2,000/$50,000 × $800,000) in the population.

As the projected misstatement of $32,000 exceeds tolerable misstatement of $10,000, further audit testing will be required.

The use of computers as a tool to perform audit procedures is often referred to as a ‘computer assisted audit techniques’ or CAATs for short.

There are two broad categories of CAAT:

- Test data

- Audit software.

Test data

Test data involves the auditor submitting ‘dummy’ data into the client’s system to ensure that the system correctly processes it and that it prevents or detects and corrects misstatements. The objective of this is to test the operation of application controls within the system.

To be successful test data should include both data with errors built into it and data without errors. Examples of errors include:

- Codes that do not exist, e.g. customer, supplier and employee.

- Transactions above predetermined limits, e.g. salaries above contracted amounts, credit above limits agreed with customer.

- Invoices with arithmetical errors.

- Submitting data with incorrect batch control totals.

Data may be processed during a normal operational cycle (‘live’ test data) or during a special run at a point in time outside the normal operational cycle (‘dead’ test data). Both have their advantages and disadvantages, for example:

- Live tests could interfere with the operation of the system or corrupt master files/standing data.

- Dead testing avoids this issue but only gives assurance that the system works when not operating live. This may not be reflective of the strains the system is put under in normal conditions.

Advantages and disadvantages of test data

Advantages

- Enables the auditor to test programmed controls which wouldn’t otherwise be able to be tested.

- Once designed, costs incurred will be minimal unless the programmed controls are changed requiring the test data to be redesigned.

Disadvantages

- Risk of corrupting the client’s systems.

- Requires time to be spent on the client’s system if used in a live environment which may not be convenient for the client.

Audit software

Audit software is used to interrogate a client’s system. It can be either packaged, off-the-shelf software or it can be purpose written to work on a client’s system. The main advantage of these programs is that they can be used to scrutinise large volumes of data, which it would be inefficient to do manually. The programs can then present the results so that they can be investigated further.

Specific procedures they can perform include:

- Extracting samples according to specified criteria, such as:

– random

– over a certain amount e.g. individually material balances or expenses

– below a certain amount e.g. debit balances on a payables ledger or credit balances on a receivables ledger

– at certain dates e.g. receivables or inventory over a certain age

- Calculating ratios and select indicators that fail to meet certain predefined criteria (i.e. benchmarking)

- Casting ledgers and schedules

- Recalculation of amounts such as depreciation

- Preparing reports (budget vs actual)

- Stratification of data (such as invoices by customer or age)

- Identifying changes to standing data e.g. employee or supplier bank details

- Produce letters to send out to customers and suppliers.

These procedures can simplify the auditor’s task by selecting samples for testing, identifying risk areas and by performing certain substantive procedures. The software does not, however, replace the need for the auditor’s own procedures.

Advantages and disadvantages of audit software

Advantages

- Calculations and casting of reports will be quicker.

- More transactions can be tested as compared with manual testing.

- The computer files are tested rather than printouts.

- Once set up can be a cost effective means of testing.

Disadvantages

- Bespoke software (specific to one client) can be expensive to set up.

- Training of audit staff will be required incurring additional cost.

- The audit software may slow down or corrupt the client’s systems.

- If errors are made in the design of the software, issues may go undetected by the auditor.

General advantages and disadvantages of CAATs General advantages of CAATs

- Enables the auditor to test more items more quickly.

- The auditor is able to test the system rather than printouts.

- Obtain greater evidence as the results of CAATs can be compared with other tests to increase audit confidence.

- Perform audit tests more cost effectively.

Disadvantages of CAATs

- CAATs can be expensive and time consuming to set up.

- Client permission and cooperation may be difficult to obtain.

- Potential incompatibility with the client’s computer system.

- The audit team may not have sufficient IT skills and knowledge to create the complex data extracts and programming required.

- The audit team may not have the knowledge or training needed to understand the results of the CAATs.

- Data may be corrupted or lost during the application of CAATs.

Developments in the use of CAATs

In the past, CAATs have been used to analyse data. The CAATs were tailored to the specific client who required significant investment and as a result were not widely used across all audits.

Technological development means it is now possible to capture and analyse entire datasets allowing for the interrogation of 100% of the transactions in a population – data analytics (DA). Whilst DA can be developed for bespoke issues, a key characteristic is that there is development of standard tools and techniques which allows for more widespread use. Some of the more widely used DA tools started out as bespoke CAATs and have been developed for wider application.

Definitions

Data analytics is the science and art of discovering and analysing patterns, deviations and inconsistencies, and extracting other useful information in the data of underlying or related subject matter of an audit through analysis, modelling, visualisation for the purpose of planning and performing the audit.

Big data refers to data sets that are large or complex.

Big data technology allows the auditor to perform procedures on very large or complete sets of data rather than samples.

Features of data analytics

- Data analytics allows the auditor to manipulate 100% of the data in a population quickly which reduces audit risk.

- Results can be visualised graphically which may increase the user-friendliness of the reports.

- Data analytics can be used throughout the audit to help identify risks, test the controls and as part of substantive procedures. The results of data analytics still need to be evaluated using the professional skills and judgment of the auditor in order to analyse the results and draw conclusions.

- As with analytical procedures in general, the quality of data analytics depends on the reliability of the underlying data used.

- Data analytics can incorporate a wider range of data. For example data can be extracted and analysed from social media, public sector data, industry data and economic data.

Example

The auditor may use data analytics to analyse journals posted. The analysis identifies:

- The total number of journals posted.

- The number of journals posted manually.

- The number of journals posted automatically by the system.

- The number of people processing journals.

- The time of day the journals are posted.

The auditor may conclude there is a higher risk of fraud this year compared with last if:

- The number of manual versus automatic journals increases significantly.

- The number of people processing journals increases.

- Journals are posted outside of normal working hours.

Benefits of data analytics

- Audit procedures can be performed more quickly and to a higher standard. This provides more time to analyse and interpret the results rather than gathering the information for analysis.

- Audit procedures can be carried out on a continuous basis rather than being focused at the year-end.

- Reporting to the client and users will be more timely as the work may be completed within weeks rather than months after the year-end.

- May result in more frequent interaction between the auditor and client over the course of the year.

- Reduction in billable hours as audit efficiency increases. Whilst this is good news for the client it will mean lower fees for the auditor.

What it means for the profession

- Larger accountancy firms are developing their own data analytic platforms. This requires significant investment in computer hardware and software, training of staff and quality control.

- Small firms are unlikely to have the resources available to develop their own software as the cost is likely to be too prohibitive. However, external computer software companies have developed audit systems that work with popular accounting systems such as Sage, Xero and Intuit which many clients of small accountancy firms may be using.

- Medium sized firms may also find the level of investment too restrictive and may therefore be unable to compete with the larger audit firms for listed company audits. However, these firms may find that listed companies require systems and controls assurance work which their auditors would not be allowed to perform under ethical standards.

Other techniques

There are other forms of CAAT that are becoming increasingly common as computer technology develops, although the cost and sophistication involved currently limits their use to the larger accountancy firms with greater resources. These include:

Integrated test facilities – this involves the creation of dummy ledgers and records to which test data can be sent. This enables more frequent and efficient test data procedures to be performed live and the information can simply be ignored by the client when printing out their internal records.

Embedded audit software – this requires a purpose written audit program to be embedded into the client’s accounting system. The program will be designed to perform certain tasks (similar to audit software) with the advantage that it can be turned on and off at the auditor’s wish throughout the accounting year. This will allow the auditor to gather information on certain transactions (perhaps material ones) for later testing and will also identify peculiarities that require attention during the final audit.

Auditing around the computer

Test your understanding 1

List FOUR factors that influence the reliability of audit evidence.

(4 marks)

Test your understanding 2

List and explain FOUR methods of selecting a sample of items to test from a population in accordance with ISA 530 Audit Sampling.

(4 marks)

Test your understanding 3

List and explain FOUR factors that will influence the auditor’s judgment regarding the sufficiency of the evidence obtained.

(4 marks)

Test your understanding 4

During the audit, the auditor will use sampling. There are a variety of sampling methods available. Some sampling methods are statistical and some non-statistical. The auditor must use an appropriate method for the item being tested.

- You have identified a higher than expected deviation rate when performing tests of controls over purchases. Which of the following would be an appropriate response?

- Pick alternative items to test in place of those just tested and ignore the deviations.

- Extend the sample size.

- Perform more substantive procedures over purchases as tests of controls have not provided sufficient appropriate evidence.

- (i) and (ii) only

- (iii) only

- (ii) and (iii) only

- (i), (ii) and (iii)

- Which of the following statements is true?

A Random sampling is a method where the auditor picks the sample with no particular pattern

B Deviations must be extrapolated to determine the effect on the population

C Block sampling is where the auditor tests all items in a population

D Monetary unit sampling is a statistical method of sampling

- Which of the following constitutes sampling?

A Where less than 100% of the items in a population are tested and have an equal chance of selection

B Where less than 100% of the items in a population are tested and have a chance of selection

C Where items within a population with certain characteristics are chosen for testing

D Where every nth item in a population are chosen for testing

- Which of the following statements is true?

A Statistical sampling methods are more reliable than non-statistical methods

B The auditor must always use stratification to ensure a representative sample is tested

C More than one sampling method may be used to test one population

D A deviation occurs when a result differs from expectation during a substantive procedure

- The auditor has identified a misstatement in a sample. Which of the following is the most appropriate initial course of action? A Consider whether the misstatement is an anomaly or

representative of further possible misstatement B Inform the client of the misstatement

C Calculate the materiality of the misstatement in relation to the financial statements

D Compare the misstatement to the tolerable misstatement level

Test your understanding 5

You are planning the audit of Wyndham Co. The company sells diamonds and other precious stones. You have decided to use the work of an auditor’s expert to provide sufficient appropriate evidence over the valuation of inventory.

- Before appointing an auditor’s expert, what factors must the auditor consider?

- Reliability of the source data.

- (i), (ii) and (iii)

- (ii), (iii) and (iv)

- (i) (iii) and (iv) only

- (i), (ii), (iii) and (iv)

- How can the auditor assess the competence of an auditor’s expert?

- Obtain copies of professional certificates and make enquiries of the expert’s experience.

- Ask for confirmation from the expert of their independence.

- Inspect the register of members of the relevant professional body for the name of the expert.

- (i) and (ii) only

- (ii) and (iii) only

- (i) and (iii) only

- (i), (ii) and (iii)

- What must be agreed with the auditor’s expert in writing before the work is performed?

- Responsibilities of each party.

- Inherent limitations of the audit.

- Deadline for the work.

- Scope and objectives.

- (i), (ii), (iii) and (iv)

- (i), (iii) and (iv) only

- (iii) and (ii) only

- (i), (ii) and (iv) only

- Which of the following statements is true in respect of the expert’s work?

- The auditor can rely on the expert’s work and does not need to review it

- The auditor may choose not to review the expert’s work if it is an area in which the auditor has knowledge or experience

- The auditor must review the assumptions and source data used by the expert to ensure they were reasonable and reliable

- The auditor will engage a second expert to review the work of the first to ensure sufficient appropriate evidence has been obtained

- Which of the following statements best describes a management’s expert?

- A management’s expert is an employee of the company

- A management’s expert is someone appointed by the company to provide evidence for the auditor

- A management’s expert is someone recommended by the auditor which management appoints to provide evidence for the audit

- A management’s expert is someone appointed by the company to provide evidence for management which may be relied upon by the auditor

Test your understanding 1

The following five factors that influence the reliability of audit evidence are taken from ISA 500 Audit Evidence:

- Audit evidence is more reliable when it is obtained from independent sources outside the entity.

- Audit evidence that is generated internally is more reliable when the related controls imposed by the entity are effective.

- Audit evidence obtained directly by the auditor (for example, observation of the application of a control) is more reliable than audit evidence obtained indirectly or by inference (for example, inquiry about the application of a control).

- Audit evidence is more reliable when it exists in documentary form, whether paper, electronic, or other medium. (For example, a contemporaneously written record of a meeting is more reliable than a subsequent oral representation of the matters discussed.)

- Audit evidence provided by original documents is more reliable than audit evidence provided by photocopies or facsimiles (fax).

Only four examples are required.

Test your understanding 2

Sampling methods

Methods of sampling in accordance with ISA 530:

- Random Ensures each item in a population has an equal chance of selection, for example by using random number tables.

- Systematic In which a number of sampling units in the population is divided by the sample size to give a sampling interval.

- Haphazard The auditor selects the sample without following a structured technique – the auditor would avoid any conscious bias or predictability.

- Sequence or block. Involves selecting a block(s) of contiguous items from within a population.

- Monetary unit sampling. This selection method ensures that each individual $1 in the population has an equal chance of being selected.

Note: Only four sampling methods were required.

Test your understanding 3

Sufficiency of evidence

- Assessment of risk at the financial statement level and/or the individual transaction level. As risk increases then more evidence is required.

- The materiality of the item. More evidence will normally be collected on material items whereas immaterial items may simply be reviewed to ensure they appear materially correct.

- The nature of the accounting and internal control systems. The auditor will place more reliance on good accounting and internal control systems limiting the amount of audit evidence required.

- The auditor’s knowledge and experience of the business. Where the auditor has good past knowledge of the business and trusts the integrity of staff then less evidence will be required.

- The findings of audit procedures. Where findings from related audit procedures are satisfactory (e.g. tests of controls over revenue) then less substantive evidence will be collected.

- The source and reliability of the information. Where evidence is obtained from reliable sources (e.g. written evidence) then less evidence is required than if the source was unreliable (e.g. verbal evidence).

Test your understanding 4

| (1) | C | Extend the sample size and perform more substantive |

| tests. The auditor should never disregard deviations or | ||

| misstatements identified during testing. | ||

| (2) | D | Option A describes haphazard sampling. Deviations are |

| not extrapolated as the deviation rate will be the same | ||

| across the population. Misstatements are extrapolated | ||

| across the population. Block sampling is where items next | ||

| to each other in the population are tested. If the auditor | ||

| tests all items in the population the auditor is not using | ||

| sampling. | ||

| (3) | B | Sampling is when each item in a population has a chance |

| of selection. They do not need to have an equal chance. | ||

| (4) | C | An auditor may use multiple sampling methods to test |

| items from the same population for example if the | ||

| population has been stratified into three sub-populations | ||

| the auditor may use random sampling to test one sub- | ||

| population, haphazard to test the second and monetary | ||

| unit to test the third. | ||

| (5) | A | If the misstatement is considered to be an anomaly there |

| is no need to perform any further testing and a conclusion | ||

| can be drawn. If the misstatement was considered to be | ||

| representative of further misstatements the auditor should | ||

| extend the sample before assessing whether the | ||

| misstatement exceeds tolerable misstatement or is | ||

| material. | ||

| Test your understanding 5 | ||||||

| (1) | A | Reliability of source data is evaluated after the expert | ||||

| has performed the work. | ||||||

| (2) | C | An independence confirmation from the expert would | ||||

| confirm objectivity but not competence. | ||||||

| (3) | B | Inherent limitations of an audit would not be | ||||

| communicated to the expert. This would be included in | ||||||

| an audit engagement letter. | ||||||

| (4) | C | The auditor cannot just rely on the expert’s work. They | ||||

| must review it to ensure it provides sufficient | ||||||

| appropriate evidence and therefore must consider the | ||||||

| assumptions and source data. If the auditor already | ||||||

| had knowledge and experience in this area there would | ||||||

| be no need to use an auditor’s expert. If the auditor has | ||||||

| evaluated the competence, capability and objectivity of | ||||||

| the expert before using them, there should be no need | ||||||

| to appoint a second expert to the review the first | ||||||

| expert’s work. | ||||||

| (5) | D | A management’s expert is appointed by management | ||||

| to produce evidence to be used by management. If the | ||||||

| evidence is reliable and relevant to the external audit, | ||||||

| the auditor may choose to rely on that work. | ||||||