Meaning of Sources of Law

The expression ” source of law” has several distinct meanings First, it may refer to the direct means by which law is made or comes into existence, that is, the legal sources,Secondly, it may mean the place where the rules of law may be found, that is, the literal sources. In this sense law reports, which publish decisions of the superior courts in actual cases, Acts of Parliament, and books of authority by writers such as Blackstone, Coke, and others are literal sources. Lastly, it may refer to factors that have influence the development of the law and to which the content of the law may be traced, that is, historical or material sources. In this sense, received English law and African customary law are historical sources of the Kenyan law. It is in the first sense, however that the expression ‘’ law” is used in this lecture.

3.4 Sources of Law in Kenya

Section 3 of the Judicator Act, 1967 provides that the courts in Kenya shall apply certain laws mentioned below while deciding certain cases before them. Thus, this section contains the sources of law of Kenya. Section 3 provides:

3 (1) the jurisdiction of the High Court, the Court of Appeal and of all subordinate courts shall be exercised in conformity with:

- The Constitution.

- Subject thereto, all other written laws, including the Acts of Parliament of the United Kingdom….

- Subject thereto, and so far as the same do not extend or apply, the substance of

the common law, the doctrines of equity and the statutes of general application in force in England on the 12th August, 1897….

Provided that the said common law, doctrines of equity and statutes of general of application shall apply so far only as the circumstances of Kenya and its inhabitants permit and subject to such qualifications as those circumstances may render necessary.

(2) The High Court, the Court of Appeal and all subordinate courts shall be guided by African customary law in civil cases in which one or more of the parties is subject to it or affected by it, so far as it is applicable and is not repugnant to justice and morality or inconsistence with any written law ….

Additional but limited sources are Islamic and Hindu law.

Thus the following, are the sources of Kenya law:

3.4.1 The Constitution of Kenya

Constitution is basic and supreme law by which a state or nation is governed. It outlines the government structure, allocation of the authority and duties of the government and places limitations on the governmental authorities.

The Constitution of Kenya is a written legal document which was initially agreed upon by citizens through their representatives and the British Government at the constitutional talks in 1960, 1962 and 1963 and came into force in December 1963. However, the present Constitution was enacted in 1969, which has been amended substantial number of times.

The Constitution is the supreme law of Kenya and therefore all organs of the state,

i.e., the legislature or National Assembly, the executive and the judiciary must abide by the constitution. Section 3 of the constitution establishes the supremacy of the constitution by providing:

This Constitution is the Constitution of the Republic of Kenya and shall have the force of the law throughout Kenya and, subject to section 47, if any other law is inconsistence with the Constitution, this Constitution shall prevail and the other law shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void.

Section 47, empowers Parliament to amend or alter the Constitution, Amendment of the Constitution, however, requires 65% vote of all the Members of Parliament excluding ex- officio members.

Take Note

| The Constitution is the supreme law of the land and therefore any law, including the legislation if inconsistent with the provisions of the Constitution, the Constitution shall prevail and that law shall be invalid and void to the extent of inconsistency. |

The Constitution declares Kenya as a Sovereign Republic and a multiparty democratic state. The areas covered by the Constitution briefly are:

- The manner of electing the President, and appointment of the Vice President, and their powers and functions.

- The election of the Prime Minister and his powers and functions

- The appointment of Ministers, Assistant Ministers and Permanent Secretaries.

- The composition of Parliament, election of Members of Parliament and their qualifications for election.

- Election of the Speaker and Deputy Speaker of the National Assembly.

- Constitution of Electoral Commission.

- Establishment of the High Court, the Court of Appeal and other courts. The appointment of judges and their tenure of office.

- The establishment powers and functions of the Judicial Service Commission.

- Protection of fundamental human rights and freedoms of the individual.

- Establishment, powers and functions of the Public Service Commission and appointments of public officers, including ambassadors.

- Trust Land.

3.4.2 Legislation

Legislation is a collection of rules passed by Parliament or made by a person or body other than Parliament, but with Parliament’s authority. The authority is a given in a Parent or enabling Act. It must be noted that legislation is superior to all other laws in Kenya except the Constitution.

That means that legislation supercedes all unwritten laws such as English common law, equity, judicial precedent and African customary law. However, where an Act of Parliament is in conflict with the Constitution then Constitution shall prevail and those provisions of the Act inconsistent with the Constitution shall be declared unconstitutional and void to the extent of inconsistency.

There are two types of the legislation – Parliamentary legislation and delegated legislation.

3.4.2.1 Primary or Parliamentary Legislation

Law enacted by Parliament is called primary or Parliamentary Legislation and is embodied in an Act of Parliament, sometimes referred to as a statute or statutory law. It is a major source of the Kenyan law.

3.4.2.1.1 Purposes of Statutory Law

The purposes of statutes or Acts of Parliament are as follows:

- New legislation: The main purpose of statutory law is to enact new legislation. This is done where it is felt that there is a need for a law to deal with certain problems faced by the community as a whole or by a particular section of the community.

- Law reform: Some statutes set out to revise or reform the substantive and procedural rules which form a certain area of law and completely change the law.

- Repeal: An Act of Parliament cannot be repealed by anybody other than

Parliament itself. It remains in force until repealed: Generally, a statute is repealed if it is considered by the public opinion or judges that particular statute is undesirable and should be abolished.

- Consolidation: Where existing legislation is gathered into one statute this is known as consolidation. This is usually done where an area of law has evolved piecemeal so that the consolidating statute may be passed to clarify the law.

- Codification: This takes place when all the law on a topic, that is, the statutory law, case law

and customary law are gathered together to form a single entity, or included in one statute.

3.4.2.2 Delegated or Subsidiary Legislation

Parliament usually delegates its legislative power to some subordinate bodies or persons such as ministers, local authorities, and statutory corporation. This type of legislation is referred to variously as delegated legislation, subsidiary legislation or subordinate legislation. This is done through an Act of Parliament. The Act giving or delegating power to legislate is known as the Parent Act or enabling Act.

A vast amount of legislation is created by delegated legislation. The total volume of delegated invariably outweighs that of parliamentary legislation i.e. statutes. The most common form of delegated legislation is called statutory instruments, when made by a minister in the form of rules and regulations. Other types of delegated legislation are local authority by-laws made by local councils in respect of matters in their areas, by-laws made by statutory corporations in respect of matters relating to their affairs, and the rules of court made by the Rules Committee in respect of the various courts, their procedures and jurisdictions.

3.4.2.2.1 Reasons for Delegated Legislation

There are a number of reasons for the use of delegated legislation. Some of them are listed below:

- Parliament scarcely has time to give proper consideration to the material which now finds its way into statutory instruments or other forms of delegated legislation.

- Delegated legislation may also cover areas which involve quite specialized technical knowledge and members of Parliament generally do not have the knowledge required to deal with the details of technical nature which is accordingly left to experts in government departments or public authorities.

- Delegated legislation allows broad and general laws to be passed by Parliament and more detailed provisions to be supplied by the relevant persons or bodies in the form of statutory instruments, by-laws, etc.

- Delegated legislation can be quickly and easily updated to cope with the changing economic and social conditions.

- Delegated legislation allows the delegate to cope with the emergency or urgent problems that may arise since the procedure in Parliament is slow, and in addition Parliament is not always in session.

3.4.2.2.2 Criticism of Delegated Legislation

Delegated legislation can be criticized for a variety of reasons:

- The main criticism is that it is undemocratic to delegate the power to make law to persons

or bodies who are not-elected. There is an exception, however, in that the local authorities’ by-laws are made by the elected representatives.

- There is inadequate Parliamentary control. Although in theory all delegated legislation may be vetted by Parliament but in practice they are so numerous and complex that

Parliament cannot do any such thing effectively.

- Delegated powers are so wide that they may be misused.

- Delegated legislation is even more complex than the legislation itself which makes the problem of understanding the law more difficult.

3.4.2.2.3 Control of Delegated Legislation

Delegated legislation can be controlled in two ways:

- Parliamentary control. Many Parent Acts contain provisions requiring delegated legislation made under them to be laid before Parliament, but they are in practice so numerous and complex that Parliament cannot effectively scrutinize them. Local bylaws have to be submitted to the minister concerned for approval. Despite such controls Parliament cannot effectively supervise the use of delegated legislation.

- Judicial control. Any scrutiny by the courts is after the event. Nevertheless delegated

legislation can be challenged in court of law on two grounds. First, that it is inconsistent with the provisions of the Constitution. It is unconstitutional and therefore null and void. Secondly, if it does not conform to the Parent Act that conferred power to make the delegated legislation then the courts can declare it ultra vires (beyond the powers) and therefore void. Delegated legislation can be substantively ultra-vires if the person or body authorized to make law had exceeded the power delegated by the Parent Act or exercised the power for another purpose rather than the particular purpose for which it was given or if its terms are unreasonable. It can be declared procedurally ultra vires in that it does not conform with the procedure laid down in the Parent Act. In Mwangi v R, the accused persons were convicted for overcharging for a haircut contrary to an order made under the price control regulations in force at that time. On appeal the conviction was quashed on the ground that the order had not been published in the Kenya Gazette as required by the law.

Activity 3.2

| Explain how far control of delegated legislation is effective in practice?

|

Take Note

| Statutory law overrides any other source of law except the Constitution, especially the case law, common law, equity and African customary law, while only Parliament itself by further legislation can override a statute. But where a statute is in conflict with the Constitution, the Constitution shall prevail. |

3.4.2.1.2 The Legislative Process or Procedure for Passing an Act of Parliament

The legislative powers of Parliament are contained in section 46 of the Constitution which empowers the National Assembly to pass statutes. A proposal for enactment by Parliament as a statute is known as a Bill. Bills are usually drafted in the office of the Attorney General by specialists. They are instructed by the particular Ministry which seeks to introduce the legislation.

Bills are of the following categories:

Public Bills, which affect the general public as whole, Private Bills, which concern a specific section of community or private persons such as a company and Private Member’s Bill which are introduced by individual members of Parliament.

Before a Bill can become an Act, it has to pass through three readings and five stages in Parliament and receive the President’s assent.

First Reading

The first reading consists of no more than reading the title of the Bill and a brief summary of contents of Bill in order to notify members that the Bill has been proposed,. It is just a formality and no debate or vote takes place at this reading.

Second Reading

The second reading is the most important stage because at this reading debate takes place on the general principles of the Bill. The mover of the Bill explains and defends it. Every member is allowed to participate in the debate. At the end of the debate the vote is taken. If the Bill sails through the second reading it goes the next stage, the Committee Stage.

Committee Stage

After the second reading the bill is referred to a committee of the whole House, that is, the whole House sitting as a committee of itself or it is sent to a select committee. Detailed analysis of the Bill takes place at the Committee Stage where the provisions of the Bill are minutely examined and if necessary amended.

Report Stage

Having been fully considered the details of the Bill, clause by clause at the committee stage, the Bill is reported back to the House by the chairman of the committee. At the report stage amendments made in committee are drawn to the attention of the House. If the House agrees with the Committee’s report, the Bill must pass its third reading.

Third Reading

In the third reading details or principles of the Bill are not debated only minor drafting changes are permitted. At the third reading a formal vote is taken and if approved the Bill is sent to receive the President’s assent.

The President’s Assent

If the President assents it becomes law. If the President refuses to assent he will sent it back to Parliament indicating specific provisions of the Bill which in his opinion should be reconsidered. If Parliament approves the recommendations by the President, the Bill will be resubmitted to the President for assent. However, Parliament may refuse to accept the recommendation and approve the Bill in its original form by sixty-five percent vote of all the members of Parliament, excluding ex-officio members. In that case the President shall assent the Bill.

After assent the Bill becomes an Act of Parliament and shall have the force of law, although it may not actually come into force until some later date specified in the Act itself or on the date to be set by the appropriate Minister who is authorized to do so by the Act or if there if no indication in the Act, then it becomes law midnight following the President’s assent. Also, it shall not be operative until published in Kenya Gazette.

3.4.2.1.3 Advantages of Statute Law

Several advantages may be claimed for statute law, in comparison with judge made law.

- If new laws have to be passed, or if an area of law needs drastic updating, then it is through an Act of Parliament that it is most easily done.

- Statute law is made in advance. If there are no statutory provisions covering a particular legal point, the parties may not know what their rights are until the court has decided the dispute between them.

- Statutory provisions are expressed more clearly and comprehensively than case law.

- Statute law can cover wide range of points.

- Law can be passed to avoid future problems.

- Statute law overrides judge-made law, but it can be challenged as being unconstitutional.

Activity 3.1

| Discuss advantages of statutory law |

3.4.3 Received English Law

When the British came to Kenya they introduced English law into Kenya which is also an important source of law. The received English law is statutory as well as judge made law. It should be noted that what is received is English law and not British law because in Great Britain there are two systems of law. The common law system which applies to England and Wales and the civil law system which applies to Scotland. The Scottish law is based on the principles of law contained in elaborate codes. Whereas the English law is basically developed by the courts although in recent times statute has also become prolific source of the English law.

By virtue of section 3(1)(c) of the Judicature Act the English statutes of general application, the substance of the common law and the doctrines of equity are applicable in Kenya.

The application of the English law, however, is subject to two conditions. First, only the English law that was in force in England on 12th August 1897 is applicable in Kenya and secondly, it applies only so far as the circumstances of Kenya and its inhabitants permit.

It must be noted that changes in English law after the date of reception are of little significance so far as Kenya is concerned. It is concerned only with the law in effect in 1897.Thus, developments in common law and equity in England after the date of reception technically have no effect on Kenyan law.

Nevertheless we find that the Kenyan courts still consider the recent developments in

English law and try to adopt them if they find it suitable to the local circumstances

3.4.3.1 English Statutes of General Application

The term ‘’statute of general application” means those British Acts of Parliament which were applicable to the people at large and to whole England. If an Act of Parliament is limited in its application to specific persons or to specific areas in England it is not a statute of general application and therefore is not part of the received law in Kenya.

Thus, all the legislation of a general nature in force in England on the date of reception are applicable in Kenya.

In Karanja v. Karanja (1976), the High Court of Kenya held that the Married Woman’sProperty ActJudicature Act.of England was a statute of general application and therefore applicable in Kenya by virtue of section 3 (1) (c) of the

Similarly, in Uganda case, Lakhani v. Vaitha (1965), the Gaming Acts of 1835 and 1845 which made gaming contracts illegal were held to be applicable in Uganda by the reception clause similar to that in Kenya in section 2 of the Uganda Judicature Act, 1962.

Certain points concerning statutes of general application may be noted:

- The statute must have been in force in England on or before the reception date. Statutes passed subsequent to the date of reception in England, have no legal effect in Kenya

- If a statute applies the whole Act or substantial part of it which applies and not merely a few

provisions.

- Repeal or amendment of statutes of general application after the date reception is of no

significance to Kenyan law. The Kenyan law is concerned only with the law in effect in

1897, and its applicability is unaffected by subsequent changes in English law.

- Interpretation of statutes of general application made by the English before 1897 is binding

on the Kenyan courts unless overruled. However, interpretations made after that date are not binding but have the persuasive authority.

3.4.3.2 The Development of English Common Law

Common law is the law made by judges. It has nothing to do with any law created or passed by Parliament. The common law of England has been developing for nearly thousand years through the system of precedent.

Originally the term ‘’common law” was used to denote the law in England which was enforced in the Kings’ courts. Prior to the Norman conquest in 1066 the law in England was based largely on local customary law. The effect of the Norman conquest was to set in motion the unification of local customs into one system of law. The various customary laws of the different regions gave way to national law. This national law comes to be known as the common law. It is called ‘’common” because it was common to the whole country, as opposed to the local customs which had previously predominated in the different regions.

Not long after the conquest, the Normans adopted the system of sending out royal justices to different parts of the country to deal with civil and criminal matters in the locality in which they arose. These judges played an important part to formulate the common law. At first they administered local customs ascertained with the help of a local jury. These judges would meet formally and informally and discuss the merits of the various customs they had discovered. Some of the customs would be rejected, whereas others gained general acceptance and gradually applied throughout the whole country. Thus the principles of law once accepted and developed by the judges formed the common law.

Problem of the writ system

The early common law was rigid and often harsh. A highly technical procedure developed in the early common law courts. Civil proceedings could only be commenced through the issue of a writ. The writ consisted of an order addressed to the sheriff of the county in which the defendant resided commanding him to secure the presence of the defendant at the trial and also outlining the plaintiff’s cause of action. There was a specific writ and form of action or procedural rules for each particular type of legal wrong, and it was vital that the plaintiff chose the right writ to fit his cause of action. If he used the wrong kind of writ or wrong kind of pleading to go with it, he would lose his action or at best have to begin it all over again. Also, if there was no recognized form of writ available to cover his grievances, he might be left with no remedy at all.

Inadequate remedies

In civil actions the only remedy which the common law could provide was award of monetary compensation or damages. In many cases damages might not be an adequate remedy. For example, for the breach of the contract, the only remedy provided under the common law was damages. There was no remedy to compel the party in breach to perform his part of the contract, especially where the subjectmatter of the contract is unique, one of its own kind.

3.4.3.3 The Development of Equity

As a result of these and other imperfections in the common law, dissatisfaction grew and the dissatisfied persons began to petition the king to provide them with a remedy. For a time the king determined these petitions himself but they become so numerous that he delegated this function to his Lord Chancellor. There were no fixed rules which the Chancellor had to apply, hence the Chancellor would decide the case as he thought fair. Eventually, a Court of Chancery was created to deal with such cases. The Court of Chancery was guided by the equity and fairness. Consequently the legal decision which Chancery Courts made come to be known collectively as Equity.

In due course of time, the Courts of Chancery evolved a body of rules, the principles of which were as firm as those of the common law. The rules of equity became uniform and certain in extent.

In practice both Common law and Equity operated as parallel systems, with each set of courts regarding itself as bound by its own judicial precedent. Ultimately the common law courts and the courts of chancery were combined together and now if a case combined elements of common law and equity; it could be heard in one court. Although the courts were combined, the two still remain distinct systems each with its own different principles.

Important contributions which equity made to the development of law may be summarized as under:

- New rights. Equity created certain new rights. Equity developed the whole law relating to

trusts, which had become an important aspect of property law. Under the law of trusts obligations of a trustee to a beneficiary were recognized and enforced. The law relating to mortgages was also developed by equity. It accepted the use of the mortgage as a method of borrowing money against the security of real property.

- New remedies. In common law the only remedy provided is damages. Equity provided

discretionary remedies, namely injunction, specific performance, rectification, rescission of a contract, quantum meruit and specific restitution of property.

- New procedures. In contrast to the rigidity of the common law Equity favored a flexible

approach. It ordered a witness by ‘’subpoena” to attend a trial, to have examined and cross examined orally, for discovery of documents and to insist on relevant question being answered. It provided for immediate sanction for contempt of court in the event of failure to comply with an order.

Take Note

| Common law and equity are unwritten laws and therefore can be superseded by the statutory law. They also apply only in civil cases and not criminal cases. |

3.4.4 Judicial Precedent or Stare Decisis

3.4.4.1 Doctrine of Judicial Precedent

The doctrine of the judicial precedent or principle of stare decisis is the process where by courts or judges apply the legal principles laid down or applied in previous cases. Stare decisismeans “Let it (the previous decision) stand”. Judicial precedent is also sometimes referred to as case law. The doctrine of judicial precedent requires that all courts are bound to follow the precedent set by the superior courts above them in the hierarchy.

The courts in deciding a case do not approach it entirely from the first principles. Rather, they consider whether such a case has previously been ruled upon by the courts, and if it has been then they may choose to decide the case before them in the same way. The decision in a previous case is a precedent. Where there is no previous decision on a point of law that has to be decided by a court, then the decision made in that case on that point of law is an original precedent.

However, a past decision is binding only if:

- The legal principle involved is the same as the legal principle in the case now before the court;

- The facts of the case before the court are substantially similar to the earlier case, and

- The earlier decision was made by a superior court above it in hierarchy.

It is not that every part of a judgement given by a court will be binding. It is only that part which contains reason for the decision which can form a binding precedent. This is known as ratio decidendi (usually abbreviated to ratio), which literally means the reason for the decision. It is defined by Michael Zender as “a proposition of law which decides the case, in the light or in the context of material facts”. Thus, only the principles of law that are essential to the decision are ratio decidendi and therefore are binding.

Intext Question

| When a decision of a highest court binds a judge in a lower court, what is it called? |

The part of the of the judgment which is not binding is known as obiter dictum (usually abbreviated to obiter), i.e. things said by the way. Obiter dictum is a judicial statement of law without any precedent value. The statements of law which do not contribute directly to the resolution of actual dispute. Although obiter dictum is not binding, it may have persuasive authority, especially when made by judges or courts of high standing.

Thus, a decision which is not binding may be a persuasive precedent, which the lower courts will consider and give due weight while deciding a case, but which does not necessarily have to be followed. Persuasive precedent comes from a variety of different sources such as obiter dicta by a higher ranking court; ratio decidendi and obiter statements by courts outside the Kenyan legal system, e.g. the House of Lords, the Judicial Committee of Privy Council, courts in New Commonwealth countries and courts in countries following a common law system, and the dissenting judgment in a case by an eminent judge.

Before any system of binding precedent can operate effectively, two important requirements must be satisfied. First, there must be a reliable system for the full and accurate law reporting. Many, but not all decisions of the superior courts, i.e. the Court of Appeal and the High Court are reported in law reports such as the Kenya Law

Reports (abbreviated as K.L.R) and the East African Law Reports (abbreviated as E.A.L.R). Secondly, there must be a clear hierarchy of courts, so as to make it clear which court’s decisions binds which other courts.

3.4.4.2 The Hierarchy of Courts

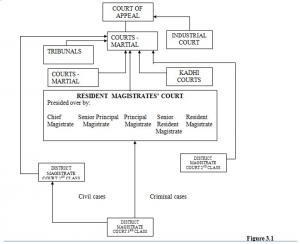

It should be noted that it is only the precedent set by superior courts, that is, Court of Appeal and the High Court that is binding on the inferior courts. Decisions of the inferior courts do not bind any court, including other inferior courts even if the decision is by the inferior court of the highest rank. Inferior Courts in Kenya include all Magistrates’ Courts, Tribunals, Kadhis’ Courts and Courts Martial.

The Judicature Act established a relatively clear hierarchy of courts, as discussed below. The structure of the courts will be discussed in detail later in this lecture, (also see figure 3.1 below)

The Court of Appeal

The Court of Appeal is the highest Court in the land and its decisions are binding on all lower courts, including the High Court. Earlier the Court of Appeal was bound by its own previous decisions, but now it would no longer regard itself as absolutely bound by its own previous decisions. For example, in Dodhia v National and Grindlays Bank Ltd (1997), the Court of Appeal stated that it was at liberty to depart from its previous decisions where it appears right to do so. The Court of Appeal being the highest court of a sovereign country is not bound by the decisions of any other court, including the House of Lords, Judicial Committee of the Privy Council and former East African Court of Appeal. Their decisions however, have a persuasive authority.

The High Court

The High Court is bound by the decisions of the Court of Appeal but it is not bound by previous High Court decisions. The decisions of the High Court are binding on all lower courts. A lower court may, however, refuse to follow a decision of the High Court if it is inconsistent with a subsequent decision of the Court of Appeal.

Other Courts

Other courts that is, inferior courts do not set any precedent and therefore their decisions are not binding on any courts. For example, District Magistrates’ Courts are not bound by the decisions of the Chief Magistrate or Senior Principal Magistrate.

3.4.4.3 Avoiding Precedents

Since precedents are binding on inferior courts, such courts are restricted even where they feel the need to depart from a precedent. However, a court may avoid following a precedent in two ways. First, by distinguishing the previous case and the case in hand by showing that the facts of the case before it are not sufficiently similar to the previous decision so as to be treated as like cases hence there is no reason why the same rule should apply to both. Secondly, where the previous decision was reached per incurium, that is, the earlier decision failed to consider some relevant statute or principle of law.

3.4.4.4 Advantages of Precedent or Case Law

- Certainty. Judicial precedent is important as it makes judge-made law certain. Legal certainty is achieved in that, if the legal problem raised has a precedent before, the judge is bound to adopt it. The certainty in the law allows lawyers to advise their clients on the probable outcome of a case.

- There is opportunity for law to develop and change with the changing needs of society.

- Practicality. The sheer volume of reported cases containing solutions to innumerable factual situations arising in real cases are practical illustration of the law.

- Time-saving device. Judicial precedent is a time-saving device, as for most situations there is an existing solutions.

- Flexibility. A general ratio decidendi may be extended to a variety of factual situations.

- Justice and Fairness. It serves the interests of justice and fairness as similar material facts will be treated in the same manner.

3.4.4.5 Disadvantages of Precedent

- The obvious disadvantage of the doctrine of binding precedent is its inherent rigidity which may cause hardship. Precedent is rigid in the sense that once the rule has been laid down it is binding even if it is considered as a bad law. The doctrine can lead to perpetuation of bad decisions for long period of time. The courts may be very slow or may not be able to rectify the problem unless a similar case comes before them. However, flexibility may be achieved by the possibility of the bad decision being overruled or by distinguishing the case before the court from the bad precedent.

- Bulk and complexity. The vast and ever increasing bulk of reported cases to which the courts and lawyers must refer to determine what the law is can obscure the basic principles. The law is complex, with too many fine distinctions.

- Artificial distinctions. In order to avoid having to follow a particular precedent, the judges may be tempted to draw vague or artificial distinctions which will introduce an element of artificiality into the law.

- Slow developments. The law is slow to develop. Even where it is clear that there is need of law reform, changes cannot be made unless a case on the particular point of law comes before the court.

- Isolating ratio decidendi. It is not always easy to ascertain what the ratio decidendiof a particular case may have been, as the judges do not always make this clear. This leads to an element of uncertainty.

Take Note

| The common law, rules of equity and judicial precedents are unwritten laws and therefore superseded by the written law, i.e. the statutory law. |

3.4.5 African Customary Law

African Customary law is the oldest source of Kenyan law, having existed in various communities and tribes long before the advent of British in Kenya. All tribes in Kenya had certain rules and customs for redressing personal wrongs. They also had some means whereby a wrong could be remedied.

African customary law is not a single uniform set of customs prevailing throughout Kenya. There are important differences between customary laws of different tribes. When British came to Kenya they did not abolish customary law but permitted it to exist side by side with the new law introduced by them. They did, however, control it within certain limits.

African customary law is still applicable in Kenya subject to four conditions.

First, it applies in civil cases only and never in criminal cases. This is because African customary law is an unwritten law and therefore by virtue of section 77 of the Constitution quoted earlier it cannot be applied to criminal matters. Also, section 3

(2) of the Judicature Act specifically provides that African customary law shall be applied only in civil cases. Secondly, it will apply only in cases when one or more of the parties is subject to it or affected by it. Thirdly, customary law will apply only if it is not ‘’repugnant to justice, and morality” Lastly, it applies only if it is not inconsistent with any written law.

InMaria GiseseAngoi v Marcella Nyomenda (1982), the High Court of Kenya had an opportunity to consider when customary law may be repugnant to justice. In that case Kisii customary law allowing women to women marriages was involved. A Kisii custom allowed a widow who had no male child of her own to marry a girl by entering into an arrangement with the girl’s parents. The widow then chooses a man from her husband’s clan who will be fathering children for her through the girl she married. This custom was held to be repugnant to justice and the marriage between the widow and the girl and was, therefore, declared as null and void.

Although the African customary law is applicable in civic cases, its scope even in civil matters is further restricted the Magistrates’ Court Act. Section 2 of this Act empowers District Magistrates Courts to deal with a claim under customary law. The Act defines a “claim under customary law” as a claim concerning any of the following matters:

- Land held under customary law

- Marriage, divorce, maintenance or dowry

- Seduction or pregnancy of an unmarried woman or girl

- Enticement of or adultery with a married woman

- Matters affecting status and in particular the status of women, widows and children, including guardianship, custody, adoption and legitimacy

- Succession, both testate and intestate and administration of estates except as regards to property disposed of by a will made under written law.

It was held inKamanzaChiway v Tsuma by the High Court that the list of claims under customary law provided by section 2 of the Magistrates’ Courts Act was exhaustive and therefore claims in tort and contract could not be entertained under the African customary law.

Intext Question

| What are the necessary conditions for the application of African customary law? | |

3.4.6 Islamic Law and Hindu Law

Islamic law and Hindu law are also sources of Kenyan law. They are limited in scope in that Islamic law applies only to persons professing Islamic faith and Hindu law applies only to Hindus.

Islamic law is based on the Holy Quran and Hadith of Prophet Mohammed. Islamic law applies only to personal matters such as marriage, divorce, personal status and inheritance. Hindu law is based on Hindu Scriptures but it is a source of Kenya law only for the purposes of Hindu marriages.

Take Note

| Islamic law and Hindu law are considered as unwritten law like African customary law and therefore inferior to the statutory law. |

3.4.7 Foreign Statutes

Apart from the laws passed by the Kenya National Assembly, several British and Indian statutes have also been made specifically enforceable and binding in Kenya. For example, The Indian Transfer of Property Act, 1882, the English Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act, 1943, the Law Reform (Married Women and Tortfeesors) Act, 1935, etcare incorporated into the Kenya Law. In addition, many other statutes from Britain, mentioned in the Judicature Act are applicable in Kenya.

3.5 The Structure and Jurisdiction of the Courts

The Kenya court structure operates at three basic levels – the Court of Appeal, the

High Court and the Magistrates Courts. The Court of Appeal, the High Court and the Industrial Court constitute the superior courts and the magistrates’ courts make up inferior (subordinate) courts.

There are other judicial or quasi-judicial bodies such as the courts martial, Kadhis’ courts, and tribunals, which are subordinate to the High Court. (See figure 3.1 below).

The Court of Appeal

This is the highest court in the country. It is established under section 64 (1) of the Constitution of Kenya. It consists of the Chief Justice and not less than two other judges referred, to as Judges of Appeal, as may be prescribed by Parliament. The number of judges of Appeal shall not exceed fourteen. However, the number of Judges of Appeal may be increased .The Judges of Appeal are appointed by the President acting in accordance with the advice of the Judicial Service Commission. The qualifications, tenure of office, remuneration, etc for the Judges of Appeal are the same as those of the puisne judges.

The Court of Appeal has it’s headquarter in Nairobi but it sits in several other places including Mombasa, Nakuru, Kisumu and Nyeri. The Court of Appeal has only appellate jurisdiction. It hears appeals from the High Court and the Industrial Court. It does not have original jurisdiction.

3.5.2 The High Court

The High Court is established by Section 60 (1) of the Constitution. The Judges of the High Court consist of the Chief Justice and such number, not being less than eleven, of other judges, referred also Puisne Judges as may be prescribed by Parliament. The number of Puisne Judges shall not exceed seventy. However, the number may be increased.

The Chief Justice is appointed by the President. The judges of the High Court are also appointed by the President but in accordance with the advice of the Judicial Service Commission. To qualify for appointment as a judge of the High Court a person must be an advocate of the High Court of Kenya for not less than seven years standing, or has been previously a judge in a commonwealth country’s court of unlimited jurisdiction or has held for at least seven years a position such as that of a state counsel in the office of the Attorney General. A judge may be removed from the office only after a special tribunal appointed to investigate him has so recommended. He can be removed on the grounds of misbehavior or inability to perform the functions of his office. The judges retire at the age of seventy four.

The headquarter of the High Court is in Nairobi but it sits in several places, including

Mombasa, Machakos, Meru, Nyeri, Nakuru, Eldoret, Kisumu, Kakamega and Kisii. The High Court has unlimited original jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters and such other jurisdiction and powers conferred on it by the Constitution or any other law. Although the High Court has unlimited jurisdiction, in practice it hears those criminal cases which cannot be tried by the subordinate courts such as murder and only civil cases which cannot be heard by any Residential Magistrate’s Court because of the lack of jurisdiction.

The High Court has supervisory jurisdiction under section 65 (2) of the Constitution in any civil or criminal proceeding before any subordinate court or court martial and may make such orders, issue writs and give such directions as it may consider appropriate for the purpose of ensuring that justice is duly administered by such courts. The High Court has an exclusive jurisdiction in the interpretation of the Constitution. Section 67 (1) of the Constitution provides that where any question as to the interpretation of the Constitution arises in proceedings in a subordinate court and the court is of the opinion that the question involves a substantial question of law, the court may or shall if a party to the proceedings so requests, refer the question to the High Court. After the decision of the High Court on the substantial constitutional issue, the subordinate court must dispose of the case in accordance with that decision.

By section 67 (4) of the Constitution there is right to appeal where a subordinate court has given a final decision in civil or criminal proceedings on a question as to the interpretation of the Constitution.

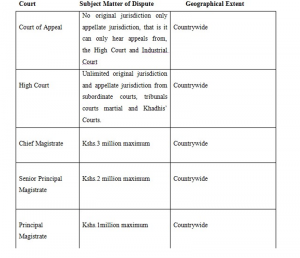

3.5.3 The Resident Magistrates’ Court

The Resident Magistrates’ Court is constituted by section 3 (1) of the Magistrate’s

Courts Act. It is duly constituted when held by a Chief Magistrate, a Senior Principal

Magistrate, a Principal Magistrate, a Senior Resident Magistrate or a Resident Magistrate. It is a court subordinate to the High court. The Resident Magistrates Court has jurisdiction to hear cases arising any where in Kenya. The civil jurisdiction the Resident Magistrates’ Court is based on the value of the subject matter in dispute.

(See Table 3.1). Under section 5 (2) of the Magistrates Courts Act, the Resident Magistrates’ Court has same jurisdiction and powers in proceedings concerning claims under the African customary law as is conferred on District Magistrates’ under section 9 (a) of the Act. This means that they can hear any case involving African customary law irrespective of the value of the subject matter.

In criminal cases, a court held by a Chief Magistrate down to a Resident Magistrate can give any sentence provided by law in cases which can be heard by them, that is in cases not heard by the High Court or could not be heard by the District Magistrates’ Courts.

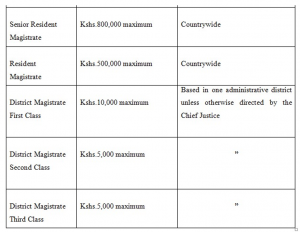

3.5.4 District Magistrates’ Courts

The District Magistrates’ Courts are established by section 7 (1) of the Magistrates’

Courts Act. District Magistrates’ Courts are of three categories, District Magistrate First class, District Magistrate Second Class and District Magistrate Third Class. Each of these courts is a court subordinate to the High Court. A District Magistrates’ Court is duly constituted when held by a District Magistrate who has been assigned to the district in question by the Judicial Service Commission. A District Magistrate Court exercises jurisdiction only within the district for which the court is established. However, the Chief Justice may extend the area of jurisdiction of a District Magistrates’ Court.

District Magistrates’ Court like the Resident Magistrates’ Courts have jurisdiction to listen to civil cases regarding claims under African customary law irrespective of the value of the subject-matter. With regard other civil matters the powers of a District Magistrate Court depends upon the value of the matter in dispute. The criminal jurisdiction of a District Magistrates’ court is limited by the maximum sentence it can impose.

All cases are normally filed in the lowest courts competent to try them. Where the suit is for compensation or damages for a civil wrong done to a person or moveable property and, if the wrong was done within the local limits of the jurisdiction of one court and the defendant resides or carries on business or personally works within the local limits of the jurisdiction of another court, the case may be filed by the plaintiff in either of these courts. Also, where the suit concerns an immovable property, the case is filed within the local limits of the jurisdiction where the property is situated.

Most of the cases start in the District Magistrates’ Courts and for this reason these courts are called courts of first instance.

For details of civil and criminal jurisdiction of courts in Kenya see charts below.

3.5.1 The Court of Appeal

This is the highest court in the country. It is established under section 64 (1) of the Constitution of Kenya. It consists of the Chief Justice and not less than two other judges referred, to as Judges of Appeal, as may be prescribed by Parliament. The number of judges of Appeal shall not exceed fourteen. However, the number of Judges of Appeal may be increased .The Judges of Appeal are appointed by the President acting in accordance with the advice of the Judicial Service Commission. The qualifications, tenure of office, remuneration, etc for the Judges of Appeal are the same as those of the puisne judges.

The Court of Appeal has it’s headquarter in Nairobi but it sits in several other places including Mombasa, Nakuru, Kisumu and Nyeri. The Court of Appeal has only appellate jurisdiction. It hears appeals from the High Court and the Industrial Court. It does not have original jurisdiction.

3.5.2 The High Court

The High Court is established by Section 60 (1) of the Constitution. The Judges of the High Court consist of the Chief Justice and such number, not being less than eleven, of other judges, referred also Puisne Judges as may be prescribed by Parliament. The number of Puisne Judges shall not exceed seventy. However, the number may be increased.

The Chief Justice is appointed by the President. The judges of the High Court are also appointed by the President but in accordance with the advice of the Judicial Service Commission. To qualify for appointment as a judge of the High Court a person must be an advocate of the High Court of Kenya for not less than seven years standing, or has been previously a judge in a commonwealth country’s court of unlimited jurisdiction or has held for at least seven years a position such as that of a state counsel in the office of the Attorney General. A judge may be removed from the office only after a special tribunal appointed to investigate him has so recommended. He can be removed on the grounds of misbehavior or inability to perform the functions of his office. The judges retire at the age of seventy four.

The headquarter of the High Court is in Nairobi but it sits in several places, including

Mombasa, Machakos, Meru, Nyeri, Nakuru, Eldoret, Kisumu, Kakamega and Kisii. The High Court has unlimited original jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters and such other jurisdiction and powers conferred on it by the Constitution or any other law. Although the High Court has unlimited jurisdiction, in practice it hears those criminal cases which cannot be tried by the subordinate courts such as murder and only civil cases which cannot be heard by any Residential Magistrate’s Court because of the lack of jurisdiction.

The High Court has supervisory jurisdiction under section 65 (2) of the Constitution in any civil or criminal proceeding before any subordinate court or court martial and may make such orders, issue writs and give such directions as it may consider appropriate for the purpose of ensuring that justice is duly administered by such courts. The High Court has an exclusive jurisdiction in the interpretation of the Constitution. Section 67 (1) of the Constitution provides that where any question as to the interpretation of the Constitution arises in proceedings in a subordinate court and the court is of the opinion that the question involves a substantial question of law, the court may or shall if a party to the proceedings so requests, refer the question to the High Court. After the decision of the High Court on the substantial constitutional issue, the subordinate court must dispose of the case in accordance with that decision.

By section 67 (4) of the Constitution there is right to appeal where a subordinate court has given a final decision in civil or criminal proceedings on a question as to the interpretation of the Constitution.

3.5.3 The Resident Magistrates’ Court

The Resident Magistrates’ Court is constituted by section 3 (1) of the Magistrate’s

Courts Act. It is duly constituted when held by a Chief Magistrate, a Senior Principal

Magistrate, a Principal Magistrate, a Senior Resident Magistrate or a Resident Magistrate. It is a court subordinate to the High court. The Resident Magistrates Court has jurisdiction to hear cases arising any where in Kenya. The civil jurisdiction the Resident Magistrates’ Court is based on the value of the subject matter in dispute.

(See Table 3.1). Under section 5 (2) of the Magistrates Courts Act, the Resident Magistrates’ Court has same jurisdiction and powers in proceedings concerning claims under the African customary law as is conferred on District Magistrates’ under section 9 (a) of the Act. This means that they can hear any case involving African customary law irrespective of the value of the subject matter.

In criminal cases, a court held by a Chief Magistrate down to a Resident Magistrate can give any sentence provided by law in cases which can be heard by them, that is in cases not heard by the High Court or could not be heard by the District Magistrates’ Courts.

3.5.4 District Magistrates’ Courts

The District Magistrates’ Courts are established by section 7 (1) of the Magistrates’

Courts Act. District Magistrates’ Courts are of three categories, District Magistrate First class, District Magistrate Second Class and District Magistrate Third Class. Each of these courts is a court subordinate to the High Court. A District Magistrates’ Court is duly constituted when held by a District Magistrate who has been assigned to the district in question by the Judicial Service Commission. A District Magistrate Court exercises jurisdiction only within the district for which the court is established. However, the Chief Justice may extend the area of jurisdiction of a District Magistrates’ Court.

District Magistrates’ Court like the Resident Magistrates’ Courts have jurisdiction to listen to civil cases regarding claims under African customary law irrespective of the value of the subject-matter. With regard other civil matters the powers of a District Magistrate Court depends upon the value of the matter in dispute. The criminal jurisdiction of a District Magistrates’ court is limited by the maximum sentence it can impose.

All cases are normally filed in the lowest courts competent to try them. Where the suit is for compensation or damages for a civil wrong done to a person or moveable property and, if the wrong was done within the local limits of the jurisdiction of one court and the defendant resides or carries on business or personally works within the local limits of the jurisdiction of another court, the case may be filed by the plaintiff in either of these courts. Also, where the suit concerns an immovable property, the case is filed within the local limits of the jurisdiction where the property is situated.

Most of the cases start in the District Magistrates’ Courts and for this reason these courts are called courts of first instance.

For details of civil and criminal jurisdiction of courts in Kenya see charts below.

Take Note

| Resident Magistrates’ Court and District Magistrates’ Courts have unlimited jurisdiction in proceedings concerning a claim under African customary law.

Since the above financial ceilings change from time to time, you must contact the court’s administrative wing about the latest ceilings. |

Criminal Jurisdiction of the Courts in Kenya

The Court of Appeal has the jurisdiction and powers to hear appeals on criminal matters from the High Court in cases in which appeals lie to it under any law.

The High Court has unlimited original jurisdiction in criminal matters. Generally it tries cases for which capital punishment or death sentence is permitted except robbery with violence.

The Resident Magistrates’ Courts have powers to pass any sentence authorized by an offence triable by that Court. The Chief Magistrate, Senior Principal Magistrate, Principal Magistrate, Senior Resident Magistrate and Resident Magistrate have jurisdiction to try offences and punish those offences in accordance with the powers given to each of them under the First Schedule to the Criminal Procedure Code. Generally these Courts try criminal cases not heard by the High Court or the District Magistrate Courts. The District Magistrate’s Court First Class has criminal jurisdiction to try and punish offences for which the sentence of imprisonment upto 7 years and/or a fine is upto Shs.20,000. The District Magistrates’ Court Second Class has jurisdiction and powers to try and punish offences for which the sentence of imprisonment is two years and/or fine is upto Shs.10,000.

The District Magistrates’ Court Third Class has jurisdiction and powers to try and punish offences for which the sentence of imprisonment is one year and/or a fine is upto Shs.5000.

Note: The criminal jurisdiction of any magistrate may be increased by the Judicial Service Commission.

3.5.5 Miscellaneous Adjudicating Bodies

These are many other judicial or quasi-judicial bodies, which cannot all be considered in detail. Such bodies include:

(i)The Industrial Court.

It is established by the Labour Institutions Act, 2007. it consist of a Principal Judge and as many judges as the President on the advice of the Judicial Service Commission may consider necessary and other members appointment by the Minister for Labour. The Principal Judge must be an advocate of the High Court of Kenya of not less than ten years standing and a judge of the High Court of Kenya of not less than seven years standing. The Industrial Court has exclusive jurisdiction in respect of matters relating to labour law and industrial relations.

The Industrial court is at the same level as the High Court and therefore appeal from this Court directly goes to the Court of Appeal. However, appeals from a judgement of the Industrial Court shall lie only in matters of law.

(ii)Kadhis’ Courts

Kadhis’ courts are established under Section 66 of the Constitution. They are courts subordinate to the High Court. Their jurisdiction is limited to proceedings relating to personal status, marriage, divorce and inheritance under the Islamic Law, in which all the parties profess the Muslim religion.

(iii)Tribunals:

These are quasi-judicial bodies which consist of both judges and non-lawyers. They are created by various Acts of Parliament to deal with certain specific matters. For example, the Restrictive Trade Practices Tribunal is established to hear appeals from the orders of the Minister for Finance on restrictive trade practices, concentration of economic power, and mergers and takeovers. Appeal from this Tribunal can be made to the High Court whose decision shall be final.

Also, there are Rent Tribunals. There are two types of Rent Tribunals. First Dwelling

Houses Tribunal established by the Rent Restriction Act and second, the Business

Premises Tribunal created by the Landlord and Tenant (Shops, Hotels and Catering Establishment) Act. Dwelling Houses tribunal has powers to assess the standard of rent of any premises, to order recovery of premises from a tenant and to order recovery of arrears of rent, service profit, or service charges. The Tribunal has also powers to order landlord to repair his premises, to permit the landlord to levy distress for unpaid rent and to reduce the standard rent where the landlord has been unable to carry out necessary repairs. The Tribunal also has power to decide whether to evict or not to evict a tenant in certain circumstances. Business Premises Tribunal’s primary function is to determine whether or not any tenancy of business premises is a “controlled tenancy”. A controlled tenancy is that which has been reduced into writing and which is for a period not exceeding five years. A controlled tenancy can only be terminated or altered in accordance with the provisions of the Act. A party wishing to terminate or alter the tenancy must give notice to the other party specifying the grounds on which the termination or alteration is sought. If the other party does not wish to comply with the notice it must refer the matter to the Tribunal. After hearing the Tribunal will make an order. Any party aggrieved by the order of the Tribunal may appeal to the High Court whose decision shall be final.

(iv) Courts Martial

They are established by virtue of section 65(1) of the Constitution. A Court Martial is a military court which is not a permanent court but it is convened from time to time to try persons accused of offences under military law. The court is dissolved as soon as the trial is over. The offences which are triable by courts martial include aiding the enemy, mutiny, insubordination, cowardice, desertion, absence without leave, neglect of duty, drunkenness etc. Appeal from the decision of the courts martial can be made to the High Court. The decision of the High Court shall be final.

Activity 3.3

|

1. Explain various sources of law in Kenya 2. Discuss the importance of Constitution and legislation in Kenyan legal system. What main purposes does legislation serve? 3. Describe the procedure to pass an Act of Parliament. 4. Explain the importance of judicial precedent. Discuss its advantage and disadvantages. 5. Describe the structure of courts in Kenya. 6. Explain briefly the jurisdiction of each court in Kenya. |

3.6 Summary Summary

|

This lecture mainly concerned itself with the sources of Kenyan law, and the structure and jurisdiction of courts in Kenya. The sources of law are the Constitution, legislation, received English law, that is, common law, equity and statutes of general application, judicial precedent, African customary law, Islamic law, Hindu law and foreign statutes. These sources are important in the sense that while deciding a case the courts must exercise their powers in conformity with these sources. Also, these sources are all not of the same importance. The Constitution takes precedence over any other law. All other written laws applicable in Kenya, namely Acts of Kenyan Parliament, those of the United Kingdom and India are superior to all other unwritten laws, that is the common law and equity, judicial precedent, African customary law, Islamic law and Hindu law and in case of conflict the written law shall prevail. However, common law and equity do not override the African customary law because they are applied in different circumstances. We have also briefly discussed the structure of courts. Court of appeal is the Apex Court but it has only appellate jurisdiction. It has no original |

|

| jurisdiction. Its decisions are binding on all lower courts.

Next is the High Court, which has unlimited original jurisdiction in both civil and criminal matters. It can try any civil or criminal case. It also has supervisory jurisdiction and powers for interpretation of the Constitution. Its decisions are binding on all subordinate courts. Several magistrates’ courts are established to resolve disputes between parties which are run by magistrates of varying seniority. They have limited jurisdictions to try civil and criminal cases. We also briefly touched on other judicial and quasi-judicial bodies which are created for specific matter. Such bodies include Industrial Court, Kadhis’ courts’ courts martial and tribunals. |

3.7 References

3.7 References

| 1. John Joseph Ogola, (1999, reprint 2005), Business Law. (Nairobi: Focus Books), Chapters 1 &2.

2. William Mbaya (1991), Commercial Law of Kenya (Nairobi: Petrans Ltd), Chapters 2 and 3. 3. Keith Abbot, Norman Pendlebury& Kevin Wardman, (2007) Business Law (London: Thomson, 8th Ed.), Chapters |