For the purpose of this chapter, PLC will be taken to mean product life cycle, and product and service will be used interchangeably. Many will be familiar with this timeless model which not only describes the stages in the sales pattern of a product or product category, but also offers some strategic directions for each stage. This model is concerned with the sales pattern & strategic directions for each stage of a product‘s life cycle. It is important to differentiate between a product’s life cycle (home loans), a product category’s life cycle (variable, fixed, no-frill) and a brand’s life cycle (Westpac, St. George‘s, BankWest, ANZ). With matured markets, the life cycle model, for strategic planning, is appropriate at the product category level where one normally finds different categories/variants at different stages of the cycle.

APPLICATION OF THE MODEL

The model can be used for analysis as well as for strategy formulation. We shall examine the former first. The PLC concept attempts to provide managers with an understanding of the characteristics of each stage of the life cycle and, therefore, can be used to predict future sales and profit patterns. Underlying the PLC concept is the theory of diffusion of innovation, which identifies categories of buyers (adopters) of the innovation. By understanding these buyers, marketers can plan for the appropriate target market strategies. The early buyers of a new product are called innovators. The numbers are very small because the new product has to prove itself. If the product is satisfactory, it will attract the next category of buyers, early adopters. Later, mainstream buyers, early and late majority, will start adopting the product. Over time, the market becomes saturated and sales come mainly from product . Eventually, sales decline as new products appear and the original product becomes obsolete. This phenomenon gives rise to the distinct S-shaped pattern of a

typical product life cycle.

The PLC concept provides a framework for developing marketing strategies in each stage of the product life cycle. Bear in mind that these strategies are appropriate for market leaders whose behaviour parallel the industry. Lesser competitors may need different strategies to compete. In some ways, the PLC model can be used as a forecasting or predictive tool. It can enable marketers to forecast the market characteristics of subsequent stages as well as predict the strategies of the leading competitors. This, of course, assumes that the life cycle exhibits the traditional pattern. Later, we will realise that many life cycle patternsare more than traditional, and the stages are of varying duration. In the following section, we shall examine the use of the PLC model both as an analytical tool and as a planning tool. These will be divided into characteristics, objectives, and strategies for each stage of the PLC.

STAGE Characteristics

When the new product is first commercialised, it enters the introduction stage of the life cycle. This stage is characterised by a slow sales growth and profits are usually negative because of the high costs of marketing associated with the introduction. Many buyers are unaware of the product and sales are limited to a category of buyers known as innovators. These buyers tend to be more affluent, venturesome and from upper social classes. Mobile phone innovators include company chief executives, sales representative, and tradespersons. These adopt the product for business use while others may buy it as a status symbol. Regardless, these buyers will be influential. There usually is no or little competition at this stage.

Primary Objectives

The main objective here for the pioneer is market expansion by stimulating primary demand, i.e., demand for the product category. For example, Apple has taken upon itself to market its innovative personal MP3 player. Sony did likewise with its personal stereo, the Walkman, in the late 1970s. The marketing objective at this stage is, therefore, to create product awareness and encourage trial.

Strategic Emphases

With innovators as the target market, the pioneering company would emphasise customer education/trial through advertising and sales promotion; and ―push‖ for trade acceptance (distribution support). The product design and function are usually very basic because of the new technology involved. Price is often cost-based and tends to be very high reflecting the ―newness‖ of the innovation and its associated R&D and marketing costs. Potential competitors, meanwhile, monitor the market closely for signs of customer acceptance.

GROWTH

Characteristics

This stage is characterised by rapidly rising sales as the product receives wide acceptance amongst the early adopters. The innovators, as opinion leaders, serve to ―legitimise‖ the innovation through product use and social interactions. The arrival of major competitors and their combined marketing strategies fuel sales growth and industry profit rises. These events necessitate different marketing objectives.

Primary Objectives

Facing competition, perhaps for the first time, the pioneering company and other leaders will need to maximize their market shares by emphasizing selective demand, i.e., demand for a particular brand. Here, the brand‘s product features and performance are stressed by extensive promotion to both the trade and customers. Stability of market shares of mainstream brands is a characteristic of the next stage, maturity. Therefore, the size of the market share gained in the growth stage will tend to persist in the maturity stage, the longest and most competitive stage of the life cycle. A brand with a small share at the end of the growth stage will find it hard to survive

in the next phase.

Strategic Emphases

The competing brands are priced to penetrate the now mainstream market, both to secure intensive distribution and build customer preference. The target market is broader in demographic terms and the product range, therefore, has to be expanded to cater to the

diverse needs of the market. The companies that enter at this stage of the PLC are often large and formidable competitors with similar access to the core/basic technology. Technological advancement is pursued vigorously for product superiority. This leads to

improvements to a product‘s form and function, i.e., the physical attributes of a product that can be evaluated objectively. Examples include frost-free refrigerators, digital mobile phones, ABS brakes and stereo video cassette recorders.

MATURITY

STAGE

Characteristics

This is, perhaps, the most important turning point of a market. Its potential indefinite duration, together with its dynamism, makes this stage the most difficult to predict or plan for. Consider the digital camera market. In the early days, they were targeted as

a computer multi-media accessory and as a status symbol. Today, they are marketed as a replacement of the conventional film-camera for anyone and everyone. Is the market now still growing or reaching maturity? Technically, a product matures when the market

has been saturated and further sales are mainly from replacements. In other words, most potential customers already have one. Who are these potential customers?

Some indicators of maturity may be helpful to analyze the market:

Sales growth and market saturation — maturity is evident when sales growth declines because the number of potential first-time buyers is decreasing. The market is said to be saturated, or fully penetrated, and sales level is maintained mainly because of replacement purchases.

Lower prices and profitability — oversupply and intense competition force prices to fall resulting in lower industry profitability.

Technological maturity and product parity — the core technology used has matured and this leads to mainstream brands all having similar product form and functions. There are very little physical differences among the competing products‘ key features. Products are usually differentiated on brand name, image and perceived quality, i.e., subjective dimensions.

Buyer knowledge — over time, buyers gain experience in the use and evaluation of the product. They may eventually accept the reality of product parity and will buy on price or convenience (economic-driven buyers) or simply on brand name (status-driven).

Primary Objectives

The main objective for most competitors is market share protection. Because the industry does not recognize the notion of a given market share starting point for each competitor, any marketing strategies can be construed as either offensive or defensive. In

a sense, market share protection is a misnomer. An aggressive competitor can claim that it is merely rebuilding lost market share (on the defence) where, in fact, it could had lost share previously by letting its guard down. Also, pro-competitive legislation may prevent businesses from having too high a market share especially through corporate takeovers. These quasi-monopolists or functional monopolists will always be under the scrutiny of the Trade Practices Commission because of their ability to control the market.

Strategic Emphases

For the reasons mentioned above, it would be difficult to generalize marketing strategies especially for the early maturity stage. The marketing mix strategies adopted in the growth stage tend to persist in the early maturity stage but with greater intensity. However, product strategies would usually involve multi-branding and an increased number of product variants/models to appeal to an even broader market. The intention is to revitalize or prolong the maturity stage through product quality improvements, functional

improvements, or style/design improvements. Recall that this stage can last indefinitely. Strategies in the late maturity/decline stages will be presented in the next section.

DECLINE STAGE

Characteristics

This stage is characterized by declining sales and profits. However, the contributing factors need to be identified and analyzed so that the business can decide on the best course of action. It is important to note that we are not concerned here with the decline stage of a brand‘s life cycle. A brand may decline due to poor marketing, etc. Rather, we are concerned with the fate of the product category‘s decline such as those evident in the case of dialup internet connections, floppy disks, CD players, CRT TV sets, etc.

These products and others have declined because of obsolescence. There are even products or models with planned obsolescence, being replaced with new models. Products become obsolete because of substitutes and forward-planning companies are usually

prepared for with these product substitutes. Buyers of these products are known as laggards. They tend to be older, more conservative and from lower socio-economic backgrounds. Their numbers are usually very small. Competition is less intense as some players are quick to exit the market (industry shake-out).

Primary Objective

Since many businesses may have a sizeable infrastructure investment in the product, e.g., plant and machinery, a quick exit may not be the best solution. The more usual move is to reduce expenditure and milk (harvest) the product. Therefore, the primary objective is to maximize cash or profit generation as quickly as possible. Another option is to maintain in, and dominate, the market when others are exiting—―a big fish in a small pond‖. There are also situations where a business can attempt to revitalize the market to create growth.

Strategic Emphases

Some options are available at this stage.

Exiting the market involves either selling the business (divestment) or liquidating existing assets such as plant and equipment. Sometimes there could be ready overseas buyers for outdated equipment especially for third world or developing countries. This should be seen as a last resort especially when milking or harvesting is not feasible. Harvesting attempts to milk the business of all available profits or cash. This is usually possible when there is still a loyal, but small, group of buyers (laggards) to maintain sufficient sales to generate profits. All marketing and overhead expenses are kept at a bare minimum in order to manage profitability and cash flow. The marketing of typewriters is a classic example.

If exit barriers exist, the business may be motivated to continue business-as-usual. This suggests allowing enough investment to maintain the business and sending a message to the competitors of its determination. An industry shake-out, typical at this stage, will

allow the surviving businesses to reap additional market share and profits from the industry. Of course, depending on the nature of the decline stage, this strategy may not be durable.

Finally, a more positive strategy would be to revitalize the market. This can be achieved by creating new uses for the product (Teflon in paints), targeting new markets (baby shampoo for adults) and product modifications/variants (breakfast cereal redeveloped and

repackaged as snack bars).

CRITIQUE OF THE MODEL

The model is not without its critics. The major criticisms of the concept can be summarized as follows:

External versus internal impact on the life cycle

The model assumes that the pattern of a product or brand‘s life cycle is influenced by the chosen strategies (internal) of the business. There is enough empirical evidence to suggest that many companies fail miserably in meeting forecast sales. We can only conclude that environmental forces (external) can play an important role in shaping the sales pattern of the product or brand.

Consider this. An unexpected turn in the environment may, in the short term, cause the sales of a product to decline. Adhering to the PLC concept a manager may misread it as the decline stage of the product‘s life cycle and act accordingly. Marketing support gets

withdrawn and this will surely kill off the product. This creates a self-fulfilling prophecy that the brand is at the end of its life.

It is, therefore, not clear how much influence a firm‘s strategy has on the life cycle. One way of resolving this argument is to consider whether pattern follows strategy or strategy follows pattern. The former assumes that the chosen strategy is the primary influence on the life cycle pattern. This is typical of proactive companies, which attempt to prolong both the growth and maturity stages through some of the aggressive marketing strategies discussed earlier.

Lesser competitors tend to be more reactive by accepting the pattern as given. They have lesser control over environmental and competitive forces. They respond by adopting strategies appropriate for each stage. In this case, strategy follows pattern.

Other PLC patterns

Not all products or brands exhibit the traditional S-shaped pattern.

Styles are common in clothing, home design and passenger cars. A style such as blue jeans may last for decades, going in and out of vogue. Fads come as quickly as they decline. They have a steep introduction stage followed by a rapid decline and are found in toys and paraphernalia associated with hit movies. Scalloped or staircase life cycles exhibit a series of upward growth-maturity stages. This

occurs when new applications of the product are found, as in nylon, Teflon, and ScotchGuard.

Varying duration

So far it is not surprising to learn that life cycles do not have a fixed pattern and that the duration of each stage varies. Also, it is not always evident when the turning point (from one stage to the next) occurs. Only a sales history can provide the evidence. By

then, it may be too late for strategy development. Within a product category life cycle, the product form and brand life cycles can exhibit contrasting patterns. Brands tend to have the shortest life cycle with the exception of ―classics‖ such as Levi‘s, Colgate, Coca-cola, Hill‘s hoist, Speedo, etc. Product forms are prone to style patterns. Moreover, there may be no clear delineation among product

forms, which could result in a strategic planning nightmare. For example, should prebrush mouth rinses be separate from traditional mouthwashes for analysis and strategy formulation? Should product forms of passenger cars be based on price range, engine

capacity (1.5 litres), body style (sedans), or body types (sports)?

Despite these limitations, the PLC model remains one of the most widely used (and misused or abused) strategic tools. The concept is simple and many of its limitations can be minimised or totally avoided through proper market definition, understanding of

key environmental forces, and careful dealing of exceptions. After all, there is no known model that can predict the dynamic and erratic marketing environment.

DIVERSIFICATION

A diversification strategy involves venturing into a new business to exploit growth opportunities in that area but is a high risk move because of the unfamiliarity with the new business. It makes sense when attractive opportunities are found outside the present

businesses. There are two types of diversification, related and unrelated.

Related Diversification

Here, the new business has some commonalities with the company‘s existing businesses. These typically involve skills and assets (resources) that can be shared for synergy or economies of scale. Related diversification is appropriate when any of the following

dimensions is present:

R&D/technology — Canon‘s photographic and electronic technologies have successfully allowed the company to diversify into photocopiers, video cameras, and printers. SaabScania boasts of its association with passenger cars, trucks, and jet fighters. Even a conglomerate like Pacific-Dunlop has many related businesses. Its tyre, rubber glove, mattress, and, industrial foam and hose businesses are all rubber/latex-based.

Brand image/association — a strong brand name can help launch a new product especially one that will directly benefit from the brand association. Matsushita‘s Panasonic brand now dons its host of consumer electrical and electronic goods. However, its Technics‘ brand is reserved for its upmarket sound systems. Levi‘s was successful when it marketed a range of casual wear but failed in the sportswear

business.

Some brands are so well positioned in a given product category that extending them to other areas can be a disaster. Windex (window cleaners) lost out when the brand was extended to other household cleaners. Xerox failed when it ventured into computers and

so did IBM when it attempted to diversify into photocopiers.

Marketing skills — the marketing functional areas most responsive to synergy are distribution and promotion. Many good products failed due to the lack of adequate distribution and are targets of takeovers. For example, a major pharmaceutical company

may diversify by taking over a failing toiletry company and relaunching the latter‘s brands through its existing distribution channels.

Traditional soft drink producers such as Coca-Cola & Pepsi have diversified into packaged snack foods, mineral water and packaged fruit juices to take advantage of their distribution and mass marketing strengths.

Unrelated Diversification

Unrelated diversification is the seeking of new businesses that have little or no relationship with the company‘s core business. By definition, unrelated diversification has few opportunities to share or exchange skills and assets across businesses. It can be

argued that the motivations for such a strategy are primarily financial. These conglomerates usually have a ―parent‖ known aptly as a holding company. Because some of these conglomerates are so diversified, the holding company or board of directors are so removed from the daily operations of each business. These businesses operate independently and are quick to be sold or new ones acquired depending on some financial criteria.

Common financial criteria include cash flow, ROI, risk spreading, and tax benefits. The text even suggested the enhancement of CEO‘s personal power. Many Japanese conglomerates have ventured into real estate, hotels, golf clubs, casinos, private colleges,

INNOVATION

Innovation is defined as revolutionalizing service delivery in terms of translating new ideas into practice, offering new customer prepositions, and implementing effective organizational change. This change adds value and is driven by one or more of the

following;- transformed inputs, process/technology, habits/behavior or mindsets, experimentation, feedback and responsiveness.

For example, innovation in the public service context has a wide scope which encompasses but is not limited to the following areas:-

- Innovation in the service delivery chain including systems, processes, operations, concepts, designs and technologies

- Innovation in the final product/service which is required by the customer

- Innovation in partnerships, participation and promoting social inclusion

- Innovation in governance and advancement in democracy

- Innovation in knowledge/information management and feedback systems

- Innovation in development of policy, strategy and leadership

- Innovation in value and legal systems, and corporate culture

- Innovation in career actualization and staff welfare

- Innovation in science and its application

- Innovation in organizational arrangements

Kenya Vision 2030 recognizes that innovation is crucial in making service delivery to the customer more efficient and effective.

Evaluation of innovations

1. Enhancement of customer satisfaction

- Ability to save time

- Reduction in cost

- Handling of feedback

- Access to service/information

- Safety and convenience

- Esteem

2. Enhancement of product or service features

- Originality

- Integration (muiltipurpose utility or application)

- Quality

- Modification

3. Service delivery processes and systems

- Automation

- Partnership arrangements

- Efficiency

- Service provider safety

- Reduction of fatigue

- Utilization of skills

- Workplace environment and safety

4. Community impact

- Effect on vulnerable groups

- Promotion of equity

- Social inclusion

- Social integration

5. Sustainability/Replication

- On the basis of local resources

- Evidence of having been instituoalized

- Simplicity in application and universal appeal.

Note.

Patenting: Individuals, groups or institutions which come up with inventions/innovations have a responsibility to make them legitimate by acquiring patents or copyrights.Innovation is not possible without knowledge. So in this session we will also cover

knowledge management. What is Knowledge? It is important to understand the concept of what is knowledge when looking at Knowledge Based Economies and Knowledge System. Knowledge can be defined as information and skills acquired through experience or education or it is a process of knowing, taking available information and translating it into action.

Knowledge is a valuable resource that holds the potential for sound governance, socioeconomic development and service delivery. Knowledge system is used to understand the process of knowledge and is often equated with ‗culture ‗ or ‗ world view‘, terms that

refer collectively to a society, its way of life and its underpinning values and beliefs. People‘s culture is not consciously learned but rather absorbed from birth throughout life. It forms the foundation of all societies by reinforcing a given society‘s way of life,

thereby giving legitimacy. Different systems of knowledge exist to allow us to understand, perceive define and experience reality.

Knowledge is an acquaintance with facts, truth or principles as from study or investigation critical for decision making. We view Knowledge in three forms, namely, tacit knowledge, explicit knowledge and Indigenous knowledge (IK).

Tacit Knowledge is Personal knowledge existing within people that enables them to know how to do things based on their experiences. This is what informs their judgment, insights, experience, know-how as well as personal beliefs and values. Explicit knowledge is documented information that can be shared with someone based on training materials read and interaction with others during training. A trainer may know the exact sequencing and/or steps in conducting and delivering his or her training. Indigenous knowledge in the other hand is traditional knowledge which requires increased focus. This has been identified through research work and documentation by coding or recoding. These are subsequently transformed into explicit knowledge through written materials and studies on the same in Africa. Indigenous knowledge thus includes African traditional knowledge systems and western knowledge systems.

Definition of Knowledge-Based Economy:

Knowledge and technology have become increasingly complex, raising the importance of links between firms and other organisations as a way to acquire specialised knowledge. A parallel economic development has been the growth of innovation in services in advanced

economies. Knowledge based economy is an expression coined to describe trends in advanced economies towards greater dependence on knowledge, information and high skill levels, and the increasing need for ready access to all of these by the business and public sectors. The recognition of knowledge as a critical element of economic growth is not new. Over the past two decades, knowledge has become the engine of the social, economic and cultural development in today‘s world, radically transforming all other dimensions of

development and the ways in which societies operate.

The issue has long been acknowledged as a factor behind the economic success of the developed world according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 1996). The OECD‘s definition of a knowledge economy (KE) focuses on sectors that apply the intensive use of technology and include services, which are also heavily knowledge-based.

Pillars of Knowledge Based Economy

There are four elements that allow effective exploitation of knowledge which are;

- An economic and institutional regime that provides incentives for the efficient use of the existing knowledge, the creation of new knowledge, and the flourishing of entrepreneurship;

- An educated and skilled population that can create, share and use knowledge well;

- A dynamic information and communication infrastructure that can facilitate processing, communication, dissemination; and finally

- An effective innovation system (i.e. a network of research centres, universities, think tanks, private enterprises and community groups) that can tap into the growing stock of global knowledge, assimilate and adapt it to local needs, while creating new knowledge and technologies as appropriate.

GLOBAL / AFRICA’S PERSPECTIVE OF KNOWLEDGE ECONOMY

The global economy is currently undergoing a major shift to a knowledge-based economy. The broad consensus, evidenced by extensive World Bank data, is that this shift presents a major opportunity for developing nations. In a knowledge-based economy, the principle means of exchange and creation of value is through knowledge. Key enablers of the knowledge value chain include the development of collaborative communities with aligned or complementary objectives and the facilitation of knowledge access designed to catalyse innovation, application and implementation.

Through embracing a knowledge-based economy, Africa can make disproportionate progress by building on its own natural strengths to overcome perceived challenges and disadvantages. By developing a knowledge-based economy infrastructure across the entire continent, Africa can overcome tendencies towards knowledge silos and socially exclusive knowledge infrastructures. Various scholars have questioned why Africa should be part of the global knowledge economy; why and how can Africa mobilise its indigenous knowledge, innovation systems and natural resources in the promotion of sustainable development and community livelihoods.

The experience in other developing countries such as South Korea, Singapore, etc. has demonstrated that knowledge is the foundation of sustainable development. A global knowledge revolution is taking place, leading to a post-industrial society. The mega-trends in this knowledge revolution and globalisation include: an explosion of telecommunications; intensified global competition; scientific advances in areas such as bio-technology; increased exchanges of technology (international licensing flows); and knowledge investments which exceed capital goods investments. It is argued that Africa missed the opportunity of going through an industrial era. Therefore, Africa now needs to take advantage of its Indigenous Knowledge and innovation systems, including resources,

to participate effectively in the knowledge revolution characterised by a shift from a resource-based to a knowledge-based economy.

Africa‘s sustained economic growth will increasingly depend on the continent‘s economic capacity for innovation, as well as its ability to produce a wider array of goods and services, to accelerate the pace of technological change and to integrate with the global economy. Enhancing this capacity will require investment in human resources development and a strengthening of the innovation environment and Africa‘s information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure.

If Africa is to benefit from the ICT revolution, more work is needed to review and modernise telecommunication policies and regulations to generate fair competition and reduce high communication and operational costs. It is this consideration that highlights

the importance of the quality of education Africa should offer, particularly tertiary education, as it is a crucial element of the capacity to innovate. Alders (2003) emphasises that innovation is the path to economic diversification and moving up the value chain. The following section looks at the role of Indigenous Knowledge (IK) and innovation systems in promoting a sustainable knowledge economy.

INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

The term Indigenous Knowledge (IK) and innovation systems refers to a distinctive body of knowledge and skills, including practices and technologies, that have been developed over many generations outside the formal educational system and which enable

communities to survive. Indigenous knowledge (IK) and innovations are a significant resource, which could contribute to the increased efficiency, effectiveness and sustainability of the development process in Africa. It is a key element of rural communities‘ social capital and constitutes their main asset in their efforts to gain control of their own lives (Mascarenhas, 2004). Full recognition and utilisation of IK may reduce the risk of creating dependency, which is often the result of developmental projects. Therefore, mobilisation of IK and innovations will assist Africa to attain the following goals:

Kayumba (1999) argues that African governments and their international aid efforts to achieve sustainable development since political independence in the 1950s and 1960s have failed. This is attributed to a number of factors related to the marginalisation and/or

distortion by imported western technologies of Indigenous Knowledge Systems and innovations.

Most development models have tended to rely on western development paradigms and structures. Hence, there was a mismatch between what local people know (IK) and western development models. Western values and technological interests are perpetuated

by the existing education systems in Africa and their western-style curricula. There was also a lack of understanding and appreciation by African governments and development agencies of the pertinent local issues and no development of a common approach by stakeholders, i.e. a participatory model, which takes into consideration local communities‘ interests and knowledge systems. Another factor is that some African elites suffer from colonised minds and do not appreciate the role of Indigenous Knowledge and

innovations in sustainable development and community livelihoods.

It is important to note that there is increasing realisation among researchers, academics, policy-makers and development agencies within and outside Africa that development efforts which ignore local circumstances tend to waste an enormous amount of time and

resources. Compared to modern technologies and approaches to sustainable community livelihood, Indigenous Knowledge and innovations have been tried and tested by the local people themselves.

They are effective, inexpensive, locally available, culturally appropriate, and based on preserving and building on the patterns and processes of nature. It is in recognition of this important role of IK and innovation systems in sustainable development, especially in

R&D, that IKS were identified as one of the flagship programme areas of the NEPAD Science and Technology.

Indigenous Knowledge (IK) and innovation systems are important because they are cumulative and represent generations of experiences, careful observations, and trial and error experimentation. They are also dynamic because new knowledge is continuously

being added through local innovations as people struggle to survive in their specific environments. In this process of innovation they use and adapt external knowledge to suit the local situations. Experience shows that African local communities have over centuries used these knowledge systems as the basis for decisions pertaining to food security, human and animal health, education, natural resources management, conflict transformation and other vital activities. IK and innovations are a key element of the social capital of the poor and constitute the main asset in their efforts to gain control of their own lives.

INTERFACE BETWEEN IK AND INNOVATIONS WITH MODERN SCIENCE &TECHNOLOGY FOR SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITY LIVELIHOODS

African indigenous knowledge systems are increasingly becoming an integral part of the global body of knowledge. Indigenous knowledge systems can be compared and contrasted with the global knowledge system (Warren, 1993) and in so doing uncover

mechanisms for evaluating the strengths and weakness of each system. This interactive flow has already resulted in mutually-beneficial exchanges of knowledge that have enhanced the capacity of the formal research system to solve priority problems identified within local communities. Both multilateral and bilateral donor agencies are now recognising the role of indigenous knowledge in sustainable development including the promotion of public health care.

Most local African communities are realising that Indigenous Knowledge and innovations continue to provide the building blocks for development and public health in most African countries, while seeking co-operation with modern knowledge for the mutual benefit of the two systems. A number of communities have demonstrated efforts made in various parts of the continent to interface African indigenous knowledge with modern knowledge systems for sustainable community livelihoods.

The Tanga AIDS Group (TAWG) in Tanzania has demonstrated a partnership between traditional healers and bio-medical practitioners to combat HIV/AIDS, and the training of traditional healers in diagnosing HIV/AIDS from a western perspective at the Nelson Mandela Medical University of Zululand. In Northern Malawi, local farmers practice ethno-veterinary work in collaboration with research and academic institutions such as the Bunda College of Agriculture (University of Malawi) and the National Herbarium in Zomba for botanical identification of the indigenous medicinal materials.

They collaborate on trials that use western scientific methods to verify the claims of the farmers. The collaboration aims to promote the conservation of medicinal plants and the complementary use of indigenous and conventional veterinary medicine for sustainable

livestock production.

KNOWLEDGE BASED ECONOMY AND KENYA’S ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AGENDA

Kenya intends to become a knowledge-led economy wherein, the creation, adaptation and use of knowledge will be among the most critical factors for rapid economic growth. The Kenya Vision 2030 recognises the role of science, technology and innovation (STI) in a

modern economy, in which new knowledge plays a central role in wealth creation, social welfare and international competitiveness.

The Kenya Vision 2030 recognises that STI will be critical to the socio-economic transformation of the country. Kenya harnesses science, technology and innovation in all aspect of its social and economic development in order to foster national prosperity and

global competitiveness. Science, technology and innovation will be mainstreamed in all the sectors of the economy through carefully-targeted investments. The introduction and use of internet in many rural areas in Kenya has impacted positively on individual lives in the rural villages making them the catalytic and developmental potential nerve of the entire economy. The internet has changed people‘s lives by empowering them to live more sustainable.

Another major innovation that is widely viewed as a success story to be emulated across the developing world is M- Pesa services, an SMS based money transfer system that allows individuals to deposit, send, and withdraw funds using their cell phone. M-PESA has grown rapidly, currently reaching approximately 38 percent of Kenya‘s adult population. The service allows users to deposit money into an account stored on their cell phones, to send balances using SMS technology to other users (including sellers of goods and services), and to redeem deposits for regular money. Charges, deducted from users‘ accounts, are levied when e-float is sent, and when cash is withdrawn.

The ongoing projects in the development of ICT in Kenya shows that people and communities in rural and urban areas benefit from ICT both socially and economically and thereby being able to use the internet for the same purposes as people in western countries, such as communicating with others, searching for information and buying goods and services. It has also been noted that Indigenous Knowledge and innovation provides the potential for local communities to go beyond poverty alleviation and generate wealth utilising their local knowledge, innovations and resources. A Case Study in Kenya by Mr. Ngumbi Kimeu of Kitui District, entitled: ‗Rethinking Indigenous Knowledge in Beekeeping for Sustainable Livelihood demonstrated how local communities in the district use their

knowledge and innovations developed over the years to promote beekeeping activities for sustainable income generation.

As envisaged in the Kenya Vision 2030, Strategies for promoting science, technology and innovation and hence the management of knowledge are;

- Strengthening technical capabilities: Kenya will strengthen her overall STI capacity. This will focus on creation of better production processes, with strong emphasis on technological learning. The capacities of STI institutions will be enhanced through advanced training of personnel, improved infrastructure, equipment, and throughstrengthening linkages with actors in the productive sectors. This will increase the capacity of local firms to identify and assimilate existing knowledge in order to increase competitiveness.

- High skilled human resources: Measures will be taken to improve the national pool of skills and talent through training that is relevant to the needs of the economy.

- Intensification of innovation in priority sectors: To intensify innovation, there will be increased funding for basic and applied research at higher institutions of learning and for research and development in collaboration with industries. Measures will be taken to identify and protect heritage. In order to encourage innovation and scientific endeavours, a system of national recognition will be established to honour innovators.

In order therefore to attain Knowledge-based economies, the following should be done;

- Provide community development services – a knowledge-sharing hub supporting a collaborative, network of knowledge networks. This can only be stimulated to develop organically – by supporting knowledge networks to address particular shared interests and goals such as, for example, government service delivery, governance, management of HIV/Aids, promotion of women‘s rights. The goal is to connect forward-thinking leadership and change agents throughout the African continent and its Diaspora, creating a strong and effective continental and global support network;

- Facilitate monitoring and evaluation, benchmarking and learning for different aspects of development and service delivery. service-delivery challenges stored and continuously improved through a shared library;

- Develop a shared knowledge repository, linked to benchmarking measures of related challenges and solutions, where solutions include action-learning resources, services and providers, and infrastructure approaches.

Knowledge is an acquaintance with facts, truth or principles as from study or investigation critical for decision making. Knowledge is informed by understanding that germinates from combination of data, information, experience, and individual interpretation is referred to as Knowledge . Within the context of organisation, knowledge is the sum of what is known and resides in the intelligence

and competence of the people. Personal knowledge existing within people that enables them to know how to do things based on

their experiences and which informs their judgment, insights, experience, know-how as well as personal beliefs and values is called tacit knowledge.

This knowledge is exhibited at individual level. For instance, one may have training materials but may not have the experience to deliver training that would lead to transfer of knowledge or skills. He or she therefore lacks the tacit knowledge which is the know-how based on previous experience. On the other hand, information that has been documented and can be shared with someone is referred to explicit knowledge. Based on the training materials read and interaction with others a trainer may know the exact sequencing of steps conduct and deliver his or her training. Though viewed as tacit knowledge, intensified activities involving research and documentation through coding or recoding will subsequently transforms IK into explicit knowledge. Practitioners observe that, much is yet to be captured and time is running out.

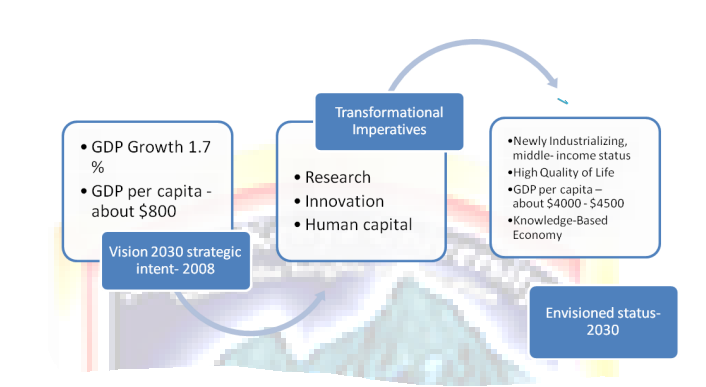

In a local example we shall deal with vision 2030 transformation as shown above.

Vision 2030 imperatives – Research

- Contextualized and applied research

- Multi-disciplinary – academia/industry/government

- Demand-led research – what are the requirements of Vision 2030? Infrastructure, economic zones, energy, ICT, construction, etc

- Funding for R & D – targeted and prioritized

- Science and technology curricula

Vision 2030 imperatives – Innovation

- New products, technology, processes, markets, ventures, and organizational models – or adoption/modifications

- Innovative capacity a function of university/industry collaborations and R&D spending

- Productivity and competitiveness – dependent on innovation and human capital

- Required – incentives for innovators – incubation, awards

Vision 2030 imperatives – Human Capital

- Human capital and Vision 2030 – Agro-processing, infrastructural development, Knowledge-intensive industries, entrepreneurship (new and innovative ventures) – these require highly skilled workforce

- Relevant knowledge for Vision 2030 at all levels – graduate and post-graduate engineers, but also intermediate and vocational training (technicians)

- Skills raise the prospect of adoption of new technologies and business opportunities

On basis of this we can conclude that:-

- The government should prioritize research funding based on relevance to development goals

- Demand-led research and skills development as opposed to reactive

- Various levels in science and technology qualifications, including intermediate (vocational) training to be given priority

- Multi-disciplinary, inter-organizational research design involving universities, government, and industry. (Industry – academic collaboration)

- Support recognized innovators and protect them through intellectual property laws

PRODUCT/SERVICE RE-ENGINEERING

Definition

This is the fundamental reconsideration and redesign of organizational products/services in order to achieve drastic improvement of current performance in cost. As organizations continue to evolve and reinvent themselves to develop new focus areas

and cater to new markets, it is imperative that their business systems do not fall behind and become obsolete. An organization should provide maintenance and reengineering services to keep its products tuned so that business needs do not outpace business

systems.

The Reengineering Process Model has the following phases:

- Product study phase

- Reengineering phase

- Regression testing phase

- Acceptance testing phase

Objectives of product/service reengineering

- Productivity and competitiveness

This emphasizes increased productivity and competitiveness as one of the key guiding principles for expanding and maintaining the domestic and export markets in a liberalized environment. - Market development

The takes cognizance of the need to diversify and expand markets for industrial value added products. It addresses supply side constraints with regard to product quality, volume and standards. - High value addition and diversification

The recognizes high value addition to the resource endowment as key for optimizing creation of wealth, employment and regional development. It therefore emphasizes on further processing of primary products. - Regional dispersion

The underscores the need for equitable dispersion of industries throughout the country in order to accelerate the pace of development especially in the marginalized areas. - Technology and innovation

The recognizes innovation as central to meeting the rapidly changing consumer tastes and preferences while also boosting productivity and competitiveness of the industrial sector. - Employment Creation

This focuses on quality and sustainable employment creation. - Environmental Sustainability

The recognizes the need to promote sustainable industrial development that upholds environmental protection, management and efficient resource utilization. - Compliance with the New Constitution and achievement of Vision 2030

This is particularly in the Public Sector . Process reengineering should be well-aligned to the provisions of the constitution and takes into account the constitutional provisions for a devolved structure of government and the particular call to encourage regional

dispersal of industries as a basis for equity and empowerment across the nation.

Education and manpower development

This recognizes that reengineering can only take place when there is a strong and well trained workforce from all levels of training.