THE BALANCED SCORECARD

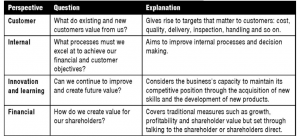

The balanced scorecard approach to performance measurement focuses on four different perspectives and uses financial and non-financial indicators.

Knowledge brought forward from earlier studies

The balanced scorecard approach emphasises the need to provide management with a set of information which covers all relevant areas of performance in an objective and unbiased fashion. The information provided may be both financial and non-financial and cover areas such as profitability, customer satisfaction, internal efficiency and innovation. The balanced scorecard focuses on four different perspectives, as follows.

Performance targets are set once the key areas for improvement have been identified, and the balanced scorecard is the main monthly report.

The scorecard is ‘balanced’ as managers are required to think in terms of all four perspectives, to prevent improvements being made in one area at the expense of another.

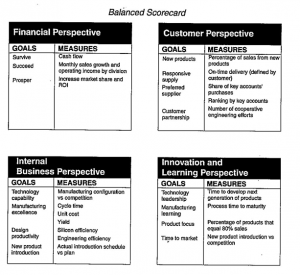

An example of how a balanced scorecard might appear is offered below.

Read the case study. You should be able to identify the perspectives as they appear here.

Case Study

The fall from grace of Digital Equipment Corporation, in the past second only to IBM in the world computer rankings, was examined in a Financial Times article. The downfall is blamed on Digital’s failure to keep up with the development of the PC, but also on the company’s culture.

The company was founded on brilliant creativity, but was insufficiently focused on the bottom line. Outside the finance department, monetary issues were considered vulgar and organisational structure was chaotic. Costs were not a core part of important decisions – ‘if expenditure was higher than budget, the problem was simply a bad budget’. Ultimately the low-price world of lean competitors took its toll, leading to huge losses. It was acquired by

Compaq which itself is now part of the HP (Hewlett Packard) group

Advantages and disadvantages of the balanced scorecard

Important features of this approach are as follows.

- It looks at both internal and external matters concerning the organisation.

- It is related to the key elements of a company’s strategy.

- Financial and non-financial measures are linked together.

As with all techniques, problems can arise when it is applied.

| Problem | Explanation |

| Conflicting measures | Some measures in the scorecard such as research funding and cost reduction may naturally conflict. It is often difficult to determine the balance which will achieve the best results. |

| Selecting measures | Not only do appropriate measures have to be devised but the number of measures used must be agreed. Care must be taken that the impact of the results is not lost in a sea of information. |

| Expertise | Measurement is only useful if it initiates appropriate action. Nonfinancial managers may have difficulty with the usual profit measures. With more measures to consider this problem will be compounded. |

| Interpretation | Even a financially-trained manager may have difficulty in putting the figures into an overall perspective. |

The scorecard should be used flexibly. The process of deciding what to measure forces a business to clarify its strategy. For example, a manufacturing company may find that 50% – 60% of costs are represented by bought-in components, so measurements relating to suppliers could usefully be added to the scorecard. These could include payment terms, lead times, or quality considerations

Case Study

An oil company (quoted by Kaplan and Norton, Harvard Business Review) ties 60% of its executives’ bonuses to their achievement of ambitious financial targets on ROI, profitability, cash flow and operating cost, and 40% on indicators of customer satisfaction, retailer satisfaction, employee satisfaction and environmental responsibility.

THE PERFORMANCE PYRAMID

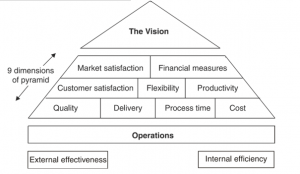

The performance pyramid highlights the links running between an organisation’s vision and its functional objectives.

The performance pyramid derives from the idea that an organisation operates at different levels, each of which has different concerns which should nevertheless support each other in achieving business objectives. The pyramid therefore links the overall strategic view of management with day to day operations.

It includes a range of objectives for both external effectiveness (such as related to customer satisfaction) and internal efficiency (such as related to productivity), which are achieved through measures at the various levels.

- At corporate level, financial and market objectives are set.

- At strategic business unit level, strategies are developed to achieve these financial and market objectives.

- Customer satisfaction is defined as meeting customer expectations.

- Flexibility indicates responsiveness of the business operating system as a whole.

- Productivity refers to the management of resources such as labour and time.

These in turn are supported by more specific operational

-

- Quality of the product or service, consistency of product and fit for the purpose for which it is intended

- Delivery of the product or service (the method of distribution, its speed and ease of management)

- Process time of all processes from cash collection to order processing to recruitment (iv) Cost, meaning the elimination of all non-value added activities

The pyramid highlights the links running between the vision for the company and functional objectives. For example, a reduction in process time should lead to increased productivity and hence improved financial performance.

BUILDING BLOCKS

Fitzgerald and Moon’s building blocks for dimensions, standards and rewards attempt to overcome the problems associated with performance measurement of service businesses.

Question

What are the five major characteristics of services that distinguish services from manufacturing. Can you relate them to the provision of a haircut?

Answer

- Intangibility. A haircut is intangible in itself, and the performance of the service comprises many other intangible factors, like the music in the salon, the personality of the hairdresser.

- Simultaneity/inseparability. The production and consumption of a haircut are simultaneous, and so cannot be inspected for quality in advance, nor returned if it is not what was required.

- Perishability. Haircuts are perishable, so they cannot be stored. You cannot buy them in bulk, and the hairdresser cannot do them in advance and keep them in store in case of heavy demand.

- Heterogeneity/variability. A haircut is heterogeneous and so the exact service received will vary each time: not only will A and B cut hair differently, but A will not consistently deliver the same standard of haircut.

- No transfer of ownership. A haircut does not become the property of the customer.

Question

Consider how the factors intangibility, simultaneity, perishability, no transfer of ownership and heterogeneity apply to the various services that you use: public transport, your bank account, meals at stalls or in restaurants, the mobile ‘phone service, your annual holiday and so on.

Knowledge brought forward from earlier studies

Performance measurement in service businesses has sometimes been perceived as difficult because of the five factors listed above, but the modern view is that if something is difficult to measure this is because it has not been clearly enough defined. Fitzgerald et al and Fitzgerald & Moon provide building blocks for dimensions, standards and rewards for performance measurement systems in service businesses.

Standards

These are ownership, achievability and equity.

- To ensure that employees take ownership of standards, they need to participate in the budget and standard-setting processes. They are then more likely to accept the standards, feel more motivated as they perceive the standards to be achievable and morale is improved. The disadvantage to participation is that it offers the opportunity for the introduction of budgetary slack.

- Standards need to be set high enough to ensure that there is some sense of achievement in attaining them, but not so high that there is a demotivating effect because they are unachievable. It is management’s task to find a balance between what the organisation perceives as achievable and what employees perceive as achievable.

- It is vital that equity is seen to occur when applying standards for performance measurement purposes. The performance of different business units should not be measured against the same standards if some units have an inherent advantage unconnected with their own efforts. For example, divisions operating in different countries should not be assessed against the same standards.

Rewards

The reward structure of the performance measurement system should guide individuals to work towards standards. Three issues need to be considered if the performance measurement system is to operate successfully: clarity, motivation and controllability.

- The organisation’s objectives need to be clearly understood by those whose performance is being appraised i.e. they need to know what goals they are working towards.

- Individuals should be motivated to work in pursuit of the organisation’s strategic objectives. Goal clarity and participation have been shown to contribute to higher levels of motivation to achieve targets, providing managers accept those targets. Bonuses can be used to motivate.

- Managers should have a certain level of controllability for their areas of responsibility. For example they should not be held responsible for costs over which they have no control.

Dimensions

- Competitive performance, focusing on factors such as sales growth and market share.

- Financial performance, concentrating on profitability, capital structure and so on.

- Quality of service looks at matters like reliability, courtesy and competence.

- Flexibility is an apt heading for assessing the organisation’s ability to deliver at the right speed, to respond to precise customer specifications, and to cope with fluctuations in demand.

- Resource utilisation, not unsurprisingly, considers how efficiently resources are being utilised. This can be problematic because of the complexity of the inputs to a service and the outputs from it and because some of the inputs are supplied by the customer (he or she brings their own hair, for example). Many measures are possible, however, for example ‘number of customers per hairdresser per day/week’. Performance measures can be devised easily if it is known what activities are involved in the service.

- Innovation is assessed in terms of both the innovation process and the success of individual innovations.

These dimensions can be divided into two sets.

The results (measured by financial performance and competitiveness) 2) The determinants (the remainder)

Focus on the examination and improvement of the determinants should lead to improvement in the results.

There is no need to elaborate on competitive performance, financial performance and quality of service issues, all of which have been covered already. The other three dimensions deserve more attention.

Flexibility

Flexibility has three aspects.

- Speed of delivery

Punctuality is vital in some service industries like passenger transport: indeed punctuality is currently one of the most widely publicised performance measures – such as waiting time at hospitals out-patients, because organisations like health centres are making a point of it. Measures public transport might include waiting time in queues, as well as late buses. In other types of service it may be more a question of timeliness. Does the auditor turn up to do the annual audit during the appointed week? Is the audit done within the time anticipated by the partner or does it drag on for weeks? These aspects are all easily measurable in terms of ‘days late’. Depending upon the circumstances, ‘days late’ may also reflect on inability to cope with fluctuations in demand.

- Response to customer specifications

The ability of a service organisation to respond to customers’ specifications is one of the criteria by which Fitzgerald et al distinguish between the three different types of service. Clearly a professional service such as legal advice and assistance must be tailored exactly to the customer’s needs. Performance is partly a matter of customer perception and so customer attitude surveys may be appropriate. However it is also a matter of the diversity of skills possessed by the service organisation and so it can be measured in terms of the mix of staff skills and the amount of time spent on training. In mass service business customisation is not possible by the very nature of the service.

- Coping with demand

This is clearly measurable in quantitative terms in a mass service like a railway company which can ascertain the extent of overcrowding. It can also be very closely monitored in service shops: customer queuing time can be measured in banks and retailers, for example.

Professional services can measure levels of overtime worked: excessive amounts indicate that the current demand is too great for the organisation to cope with in the long term without obtaining extra human resources.

Resource utilisation measures

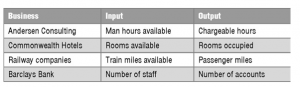

Resource utilisation is usually measured in terms of productivity. The ease with which this may be measured varies according to the service being delivered.

The main resource of a firm of accountants, for example, is the ”time” of various grades of staff. The main output of an accountancy firm is chargeable hours.

In a restaurant it is not nearly so straightforward. Inputs are highly diverse: the ingredients for the meal, the chef’s time and expertise, the surroundings and the customers’ own likes and dislikes. A customer attitude survey might show whether or not a customer enjoyed the food, but it could not ascribe the enjoyment or lack of it to the quality of the ingredients, say, rather than the skill of the chef.

Here are some of the resource utilisation ratios listed by Fitzgerald et al.

Innovation

In a modern environment in which product quality, product differentiation and continuous improvement are the order of the day, a company that can find innovative ways of satisfying customers’ needs has an important competitive advantage.

Fitzgerald et al suggest that individual innovations should be measured in terms of whether they bring about improvements in the other five ‘dimensions’.

The innovating process can be measured in terms of how much it costs to develop a new service, how effective the process is (that is, how innovative is the organisation, if at all?), and how quickly it can develop new services. In more concrete terms this might translate into the following.

- The amount of R&D spending and whether (and how quickly) these costs are recovered from new service sales

- The proportion of new services to total services provided

- The time between identification of the need for a new service and making it available

Now look at the Example below using your knowledge of the model.

Points to consider

There is some debate as to how far the links between the financial results and the determinants of those results can be precisely identified. Better quality will please customers, but there is a problem of short-term versus long-term benefits. Quality costs money now, while the benefits may take a long time to come through.

There is also the question of how much quality is enough: endless improvements that cost a lot of money, but are not necessarily sought by the customers (who may indeed be unwilling to pay for them) will harm long-term profitability.

Be prepared to think up performance measures for different areas of an organisation’s business. Remember to make the measures relevant to the organisation in question. There is little point in suggesting measures such as waiting times in queues to assess the quality of the service provided by an educational establishment.

Question

Suggest two separate performance indicators that could be used to assess each of the following areas of a fast food chain’s operations.

- Food preparation department

- Marketing department

Solution

Here are some suggestions.

Material usage per product

Wastage levels

Incidences of food poisoning

Market share

Sales revenue per employee

Growth in sales revenue

CHAPTER ROUNDUP

- The balanced scorecard approach to performance measurement focuses on four different perspectives and uses financial and non-financial indicators.

- The performance pyramid highlights the links running between an organisation’s vision and its functional objectives.

- Fitzgerald and Moon’s building blocks for dimensions, standards and rewards attempt to overcome the problems associated with performance measurement of service businesses.