3.1 Introduction

Many chief executives consider the make-or-buy decision to be among the most critical and most difficult confronting their organizations. Not only are billions of dollars needlessly wasted if the wrong decision is made, but scarce management resources frequently are stretched past the breaking point. Outsourcing is a term being used in relation to services such as accounting, maintenance, security, promotion, stocking, and the like. The basic issues are the same concerning the question of doing it yourself or contracting with an independent outside the buying firm. The strategic issue requires the firm to identify its core competencies-the things that differentiate it and make it viable. If an item or service at or near the heart of the firm’s core competencies is to be outsourced, it should only be supplied by a carefully selected supplier under a tightly woven strategic alliance.

Top management has the ultimate responsibility for make-or-buy decisions. In most cases, this responsibility can be satisfied through operating procedures that develop and pool all relevant information surrounding a make-or-buy issue. Purchasing is a source of much of this information. Also, Purchasing frequently should identify candidates for a make-or-buy analysis.

Five major problems are common in the make-or-buy area namely:

1. Make-or-buy decisions are made at too low a level in the organization.

2. Not all factors are considered when conducting a make-or-buy analysis.

3. Decisions are not reviewed on a periodic basis. Circumstances change!

4. The estimates underlying the cost of making are less objective and accurate than the purchase facts.

5. Members of the buying company assume they know more than the supplier about the material or service.

3.2 Make or buy issues

The Strategic issues

“What kind of an organization do we want to be?” This issue is the first, and perhaps most critical, to be addressed. Pride or purely emotional reasoning plays a major part in many decisions. Pride in Self-sufficiency can become a dominant factor that can lead to many problems. While self sufficiency in some areas is desirable or even necessary, it is impossible for even a large firm to

become entirely self-sufficient.

These decisions influence the firms manufacturing operation shape and capacity by determining;

- What product to make

- What investments to make in plant and equipment

- The framework for short term tactical and component decisions.

- Development of new products.

Tactical make or buy decisions

This deal with the issue of temporary imbalance in manufacturing capacity e.g. changes in demand may make it possible to make everything in house.

Component make or buy decisions

Made at the design stage, these decisions have to do with whether a particular component should be made in – house or is bought.

Costs

Two keys prerequisites are essential to a thorough and sound analysis of the cost considerations of a make-or-buy decision.

- Cost must be segregated between fixed costs and variable or incremental ones. Such cost figures must include all relevant costs, both direct and indirect, near term and anticipated changes. Realistic estimates of in-house production costs must include expected rejection rates and spoilage. These estimates also should consider the likely effects of learning resulting from long production runs.

- Accurate and realistic data must be available on the investment required to make or to buy an item. Frequently, the working capital required in the manufacture of an item can equal and even exceed the investment required for facilities and equipment. It is essential to consider both the facilities and the working capital components of an investment. Cost factor in make or buy decisions often require the application of marginal costing and break – even analysis

1. marginal costing

this is a principle whereby valuable costs are charged to cost units and the fixed costs attributable to the relevant period written off in full against the contributions for that period contribution = purchase price – vc per them

Example;

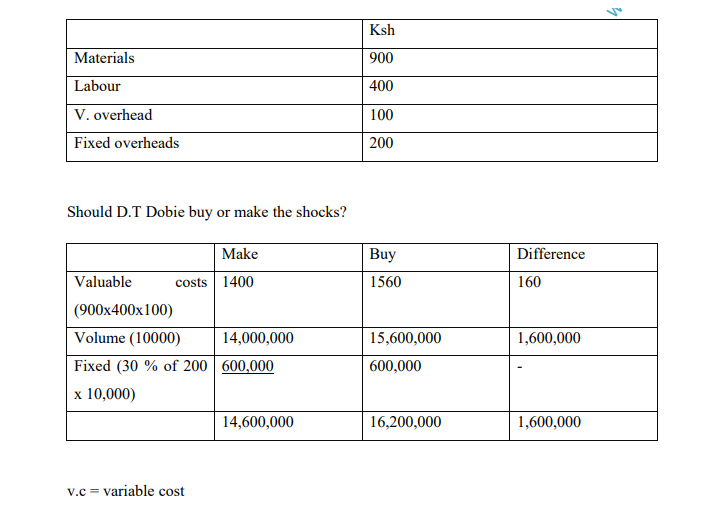

D.T. Dobic requires 10,000 shock absorbers for the assembly of Nissan pick ups in Kenya. The company could make this shock absorbers ltd which sells its shocks at ksh 1560. Only 30% of the fixed costs are recoverable if the component is bought. The following are the costs that D.T. Doble would incur should it decide to make the shocks.

In consequences buying instead of making profits would reduce by ksh 1,000,000. (15c – 146). It is therefore advisable to make the shocks. This decision is made in light of the fact that fied costs of ksh 600,000 would likely continue since the capacity would be unused the fixed overheads would not be absorbed into production.

2. opportunity cost

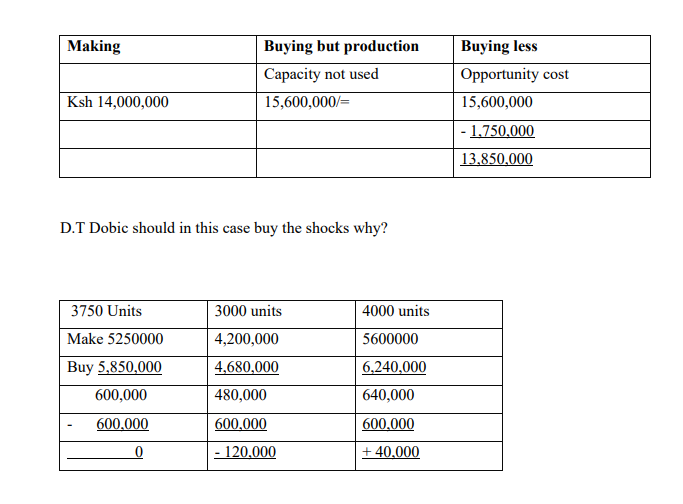

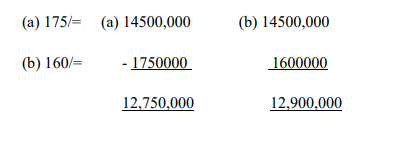

This is the potential benefit that is foregone because one course of action has been chosen over another. I.e. if the production facilities used in making the item had been applied to some alternative purpose. Using the D.T Dobic example, if instead of producing the shocks the facilities could be used to make suspension springs with a contribution of ksh 175 each. Should D.T Dobic make the shocks or buy.

example II – break when analysis

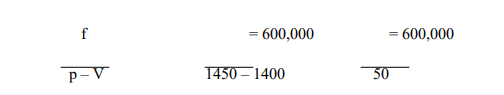

What would be the decision points if the price of the shocks were reduced from 1560 to 1450/=

Using Break even analysis

They would need to produce 12,000 units to break even since the firm needs 10,000 shocks then they would rather buy.

Example II – opportunity cost

Valuable D.T Dobic makes or buy the shocks

1. The contribution of the suspension springs reduce of from 175/= to 160/= – 15600000 – 160 000000 – same cost structure this indifference

2. The price of the shocks reduced from 1560/= to 1450/= with the contribution of the suspension springs at

1. They should buy the shocks

2. They should buy the shocks.

If D.T Dobic buys the shocks and uses the facilities to make suspension springs the cost structure for both activities will be 13,850,000/= against a cost structure of 14,000,000 were the firm to make the shocks instead. Thus in buying the shocks DT Dobic will have made/ earned ksh 150,000 (14,000,000 – 13,850,000)

Learning curves / skill acquisition / experience curve

This a graphical representation of the rate at which skills or knowledge is acquired is a period of time. The basis of learning curves is that “skill to do come by doing. I.e. A task is performed more quickly with each subsequence replication until a point is reached where no further improvement is possible and performance levels out. The learning curve theorem states that each time the number of production units is doubled, the cumulative average lab our hrs per unit’s previous cumulative average.

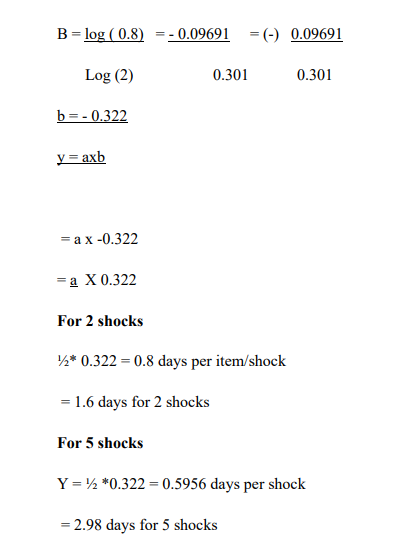

The learning curve equation is y = a x6

Where y = cumulative average time per unit

X = number of units produced so far

A = time taken to produce the first item

B = log (learning rate)

Log (2)

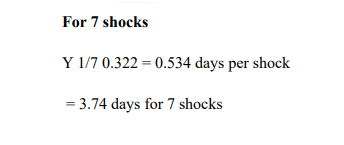

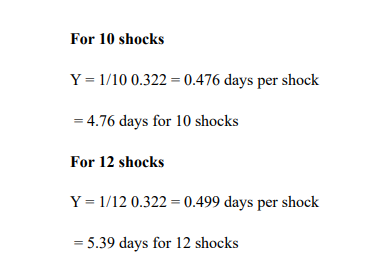

E.g. if the learning rate to produce shock absorbers is 80% and it requests 1 day to produce one shock absorber, then to produce 2 shocks is 1.6 days with a cumulative average of

0.8 days and for 8 shock is 4.10 days with a cumulative average of 0.51 days per shock etc

The graph is then plotted using cumulative average time against units produced. When components are bought from specialist manufacturers there may be little opportunity for learning. When items are new the costs of making and buying may have to be adjusted for the learning factors.

Other considerations in make or buy decisions

Infavour of making

1. Cost considerations

The major elements of the cost considerations are:

- Materials and labour costs

- Follow on costs stemming from quality related problem

- Incremental inventory carry on costs

- Incremental factory overhead costs

- Incremental management costs

- Incremental purchase costs

- Incremental costs of capital

2. Desire to integrate plant operations

3. Reproductive use of excess plant capacity to help absorb fixed costs

4. Need to exert direct control over production and /or quality.

5. Design secrecy required

6. Unreliable suppliers

- Desire to maintain a stable work force (in periods of low sales )

- Potential lead time reduction

- Exchange rate risk

- Greater purchasing power with bulk purchase of materials.

Quality

When there is a significant difference in quality between items produced internally and items purchased or when a specified quality cannot be purchased, then management must consider these quality considerations in the make-or-buy decision. One argument for making over buying is the so-called impossibility of finding a supplier capable or willing to manufacture the item to the desired specifications. But further investigation should be conducted before this argument can be accepted.

Why are these specifications so much more rigid than those of the rest of the industry? The Manufacturer should reexamine the specifications and make every effort to secure the cooperation of potential suppliers to ensure that the quality specifications are realistic and that no satisfactory product is available. Frequently, suppliers can suggest alternatives that are just as dependable if they know the intended purpose of the item. On the other hand, the firm may desire a level of quality below that commercially available.

Suppliers may be selling only a quality far above that which would fully satisfy the need in question and may, at the same time, have so satisfactory a volume at the higher level as to have no interest in a lower quality product. If this is the case, the user may be justified in manufacturing the item.

Frequently, it is claimed that in-house production may better satisfy manufacturing’s quality requirements. The user of an item usually better understands the operational intricacies involved in the item’s use. With a make decision, a better degree of coordination will probably exist between those responsible for producing the item and those responsible for assembling it. Communications

between the two groups are facilitated compared with the situation in which the item is furnished by an outside supplier. If the firm has a weak purchasing department, such assumptions may be true. But with a professional purchasing operation, the flow of information and coordination between purchaser and supplier should result in no more problems than between two production

activities of the same firm.

Since quality must be controlled in either the purchased or manufactured items, a competent quality assurance staff and a TQM (total quality management) program must be employed. The purchase order may state that the purchaser’s quality assurance inspectors have access to the supplier’s manufacturing, inspection, and shipping departments. Thus, the purchaser can maintain significant control and still not incur the additional cost resulting from manufacturing the item.

Quantity

One of the most frequent reasons for making over buying is that a requirement may be too small to interest suppliers. Small volume requirements of unique, nonstandard items may be difficult to purchase. The firm may feel that it is forced to make such items; however, it may be economically imprudent to do so. The costs of planning, tooling, setup, and purchase of required raw materials

may be exorbitant. It may be far more cost effective to purchase the required item in larger quantities or to identify a suitable substitute.

If a large quantity of an item is required on a repetitive basis, then the analysis described in the Cost section should be made. The company should have a high degree of confidence that its requirements for the item will continue to the point that it receives a satisfactory ROI before deciding to make such an item.

Frequently a firm will follow a conscious policy of making an item at a level of production sufficient to meet its minimum requirements and purchase additional items as required. This policy builds a degree of stability into the firm’s production activities and provides accurate comparative cost data. Such a policy should be adopted only after investigating the willingness and ability of

suppliers to fill such fluctuating demand.

Service

Service often is defined simply as reliable delivery. In a broader sense, it includes a wide variety of intangible factors that lead to greater satisfaction on the part of the purchasing firm. This consideration must be judged fairly and the purchasing firm must not be given undue credit with ] respect to service simply for emotional reasons. Merely because the item is produced in-house is

not proof that service will be superior to that of a supplier. Assurance of supply is a primary service consideration. When the lack of an item causes serious problems, such as total production stoppage, and totally reliable suppliers are not available, the decision to make rather than buy may be justified.

When a purchaser is faced with a monopolistic environment, the service accompanying the product is generally somewhat poorer than in a highly competitive market. Such a situation may induce the would-be purchaser to make the product. If an item is used as a subcomponent on a product the purchaser is selling and is causing the entire product to be unreliable, the resulting loss of goodwill

and sales may be significant enough to justify a make decision, even though the cost analysis does not support such a decision.

Specialized Knowledge

Frequently, a supplier possesses specialized knowledge, abilities, and production know-how that would be very expensive to duplicate. Suppliers may have a large R&D budget leading to improved and/or less expensive products. The protection of innovation achieved by the supplier is a critical aspect of trust, that is, the buyer must not under any condition give this innovation to a supplier’s competitor or use the technology were it to make the item.

Design or Production Process Secrecy

Occasionally, a firm decides to manufacture a certain part because additional industrial security can be provided, especially when the item is a key part for which a patent would not provide adequate protection. This justification must be used with caution, however, as the firm can provide very little protection against design infringement after sale. In short, if a patent will not protect a certain part, then in-house manufacturing may not either. Frequently, a firm may have developed a unique or proprietary production process. Such circumstances may support a decision to make over buying.

Urgent Requirements

The firm usually can purchase a small quantity much more readily than were it to produce the item. If the requirement is urgent, such as to preclude stopping an assembly line, the payment of a higher price to buy the item is justified.

Labor Problems

The production of any new item may require labor skills that the company does not possess. The hiring, cross-training, and upgrading of personnel may be a troublesome and complex process, especially if a union is involved. The company may be entering a field in which it has no experience and no adequately trained personnel. Labor problems are easily shifted to someone else, namely, the supplier, through a decision to buy. The presence of unions within the company also may be a significant factor. Unions often have

clauses in their contract prohibiting the purchasing of items that can be manufactured within the plant. The history of labor problems in the supplier’s company also may influence the make-or-buy decision.

Plant Capacity

Obviously the more significant the item in question is relative to the company’s size, the greater the probability that the item will be purchased rather than produced in house. When the item would require a significant investment, the smaller company has no rational decision other than to buy. Generally the more mature company will try to integrate items currently purchased into its production more often than will a new company. The new company understandably concentrates on increasing output and has very little excess capital or plant capacity to divert to production of components. Quite the opposite is true for the more mature company. Such a firm tends to have extra facilities, capital, and personnel and, therefore, is in a better position to increase profit by producing what was formerly purchased. Excess plant capacity and the likely duration of the excess capacity should always be considered in the make-or buy decision as should additional expenses such as tooling, setup, and training.

Capital Equipment

Manufacturers sometimes find it necessary to make a needed item, simply because a suitable supplier does not exist. This is most frequently the case with highly specialized manufacturing equipment.

Use of Idle Resources

A make decision can prove profitable to a firm even when suitable supplies are available. In periods of1 recession or business slumps, a firm is faced with the problem of idle plant equipment, labor, and management. By making a product that it may have been buying, a firm can put its idle machinery to work, retain skilled employees, and spread its overhead costs over a larger volume of production.

Perhaps the biggest benefits obtained from a make decision during a slump are in the area of labor relations. Employee morale can be maintained and layoff penalty costs can be avoided by timely use of the make decision. Even in times of recession, most firms find it desirable to retain highly skilled production personnel. These personnel can be kept at work and a stable workforce maintained by a decision to make. The long-run benefits from good labor relations are obvious. Great caution must be taken when basing a make decision primarily on temporary idle resources. Make decisions tend to be permanent. A decision to make temporarily an item under such circumstances should be reviewed when demand increases.

3.3 Make and Buy

Some firms make and buy critical nonstandard items to ensure that a reliable second source is available in case of difficulty with the supplier. Such a policy also provides data that are useful in reviewing internal production and management efficiency.

Making the Decision

Make-or-buy decisions can have a critical effect on the economic health of a firm, even on its survival. Frequently, these decisions are made at too low a level in the organization. On many occasions, no conscious decision appears to have been made. Things just happen! The decision to make is often weaker than the decision to buy because buy costs are known whereas make costs are estimates.

Obviously, the amount of time and effort and the level of managerial attention appropriate are functions of the amount of money involved and the criticality of the item to the firm’s well-being. Normally several departments should be interested and involved in make-or-buy decisions:

Production, Purchasing, Engineering, Finance, and Marketing.

Any of the following situations should precipitate a make-or-buy analysis:

- New product development and modification. Every major component should be reviewed.

- Unsatisfactory supplier performance. If purchasing is unable to develop reliable sources for an item, the item should be reviewed and analyzed to ensure that the specified quantity level is essential and to ensure that suitable substitutes are not available. If the item, as specified, passes these reviews, it becomes a candidate for in-house sourcing.

- Changes in sales. Sales demand that exceeds capacity calls for a make-or buy review of those items produced in house that contribute the lowest ROI. Declines in sales and production should prompt a review of candidates for in-house production.

- Periodic review of previous decisions. Changing costs and other considerations can convert a good make-or-buy decision into a bad one very quickly. Major make-or-buy decisions should be reviewed as a component of the firm’s annual planning process.

3.4 OUTSOURCING

This is the strategic use of resources to perform activities traditionally handled by international staff and their resources. An alternative definition is the buying in of components, sub – assemblers finished products and service from outside suppliers rather than supplying them internally. It is strategy by which an org outstand. The term “outsourcing” probably refers to buying materials or components from suppliers instead of making then in-house. It also refers to buying materials or components that were previously made in-house. In recent years, the trend has been moving toward outsourcing combined with the creation of supply chain relationships, although traditionally firms preferred the make option by using backward and forward vertical integration. Backward vertical integration refers to acquiring upstream suppliers, whereas forward vertical integration refers to acquiring downstream customers. For example, an end-product manufacturer acquiring a supplier’s operations that supplied component parts is an example of backward integration. Acquiring a distributor or other outbound logistic providers would be an example of forward integration.

Whether to make or buy materials or components is a strategic decision that can impact an organization’s competitive position. It is obvious that most organizations buy their MRO and office suppliers rather than make the items themselves. Similarly, seafood restaurants usually buy their fresh seafood from fish market. However, the decision on whether to make or buy technically

advanced engineering parts tat impact the firm’s competitive position is a complicated one. Traditionally, cost has been the major driver when making sourcing decisions. However, organizations today focus more on the strategic impact of the sourcing decision on the firm’s competitive advantage. Generally, organizations outsourcing noncore activities while focusing on core competencies.

Finally, the make-or-buy decision is not an exclusive either-or option. Firms can always choose to make some components or services in-house and buy the rest from suppliers.

3.5 Reasons for buying or Outsourcing

Organizations buy or outsource materials, components, and/or services from suppliers for many reasons.

1. Cost advantage: For many firms, cost is an important reason for buying or outsourcing, especially for supplies and components that are nonvital to the organization’s operations and competitive advantage. This is usually true for standardized or generic supplies and materials for which suppliers may have the advantage of economies of scale because they supply the same items to multiple users. In most outsourcing cases, the quantity needed is to small that it does not justify the investment in capital equipment to make the item. Some foreign suppliers may also offer cost advantage because of lower labour and/or materials costs.

2. Insufficient capacity: A firm may be running at or near capacity, making it unable to produce the components in-house. This can happen when demand grows faster than anticipated or when expansion strategies fail to meet demand. The firm buys parts or components to free up capacity in the short term to focus on vital operations. Firms may even subcontract vital components and/or operations under very strict terms and conditions in order to meet demand. When managed properly, subcontracting, instead of buying, is a more effective means to expand short –term capacity because the buying firm can exert better control over the manufacturing process and other requirements of the component parts or end products.

3. Lack of expertise: The firm may not have the necessary technology and expertise to manufacture the item. Maintaining long term technological and economical viability for noncore activities may be affecting the firm’s ability to focus on core competencies. Suppliers may hold the patent to the process or product in question, thus precluding the make option, or the firm may not be able to meet environmental and safety standards to manufacture the item.

4. Quality: Purchased components may be superior in quality because suppliers have better technology, process, skilled labor and the advantage of economies of scale. Suppliers may be investing more in research and development. Suppliers’ superior quality may help firms stay on top of product and process technology, especially in high-technology industries with rapid innovation and short product life cycles.

An organization also makes its own materials, components, service and/or equipment in-house for many reasons. Let us briefly review these reasons;

1. Protect proprietary technology: A major reason for the make option is to protect proprietary technology. A firm may have developed an equipment, product, or process that needs to be protected for the sake of competitive advantage. Firms may choose not to reveal the technology by asking suppliers to make it, even if it is patent. An advantage of not revealing the technology is to be able to surprise competitors and bring new products to market ahead of competition, allowing the firm to charge a price premium.

2. No competent supplier: If the component does not exist, or suppliers do not have the technology or capability to produce it, the firm may have no choice but to make an item inhouse, at least for the short term. The firm may use suppliers development strategies to work with a new or existing supplier to produce the component in the future as a long-term strategy.

3. Better quality control: If the firm is capable, the make option allows for the most direct control over the design, manufacturing process, labour and other inputs to ensure that high quality components are built. The firm may be so experienced and efficient in manufacturing the component that suppliers are unable to meet its exact specifications and requirements. On the other hand, suppliers may have better technology and processes to produce better quality components. Thus, the sourcing option ensuring a higher quality level is a debatable question and must be investigated thoroughly.

4. Use existing idle capacity: A short term solution for a firm with excess idle capacity is to use the excess capacity to make some of its components. This strategy is valuable for firms that produces seasonal products. It avoids laying off skilled workers and, when business picks up, the capacity is readily available to meet the demand.

5. Control of lead-time, transpiration, and warehousing cost: The make option provides easier control of lead time and logistical costs since management controls all phases of the design, manufacturing and delivery process. Although raw materials may have to be transported, finished goods can be produced near the point of use, for instance, to minimize holding cost.

Outsourcing can be described as the transfer of activities, that were previously conducted in-house, to a third party. Ellram and Billington (2001) see outsourcing primarily as the transfer of the production of goods or service that had been performed internally to an external party. Outsourcing means that the company divests itself of the resources to fill a particular activity to another company to focus more effectively on its own competence. The difference with subcontracting is the divestment of assets, infrastructure, people and competencies.

3.6 Types of outsourcing

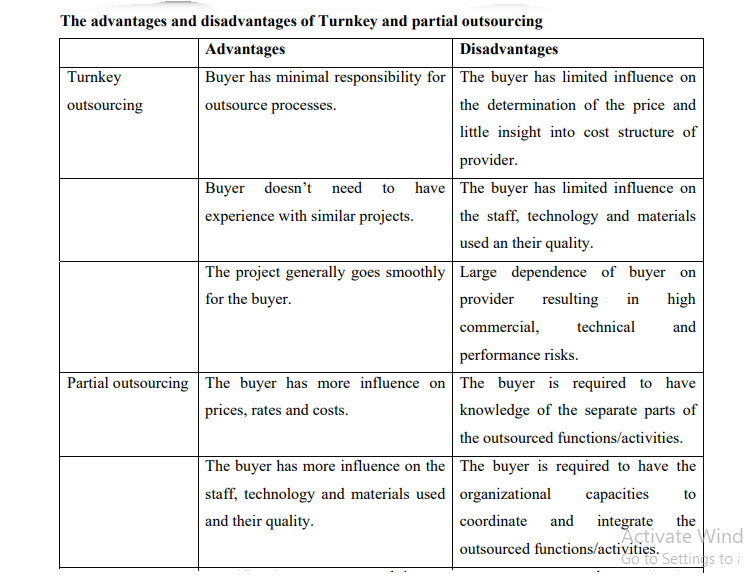

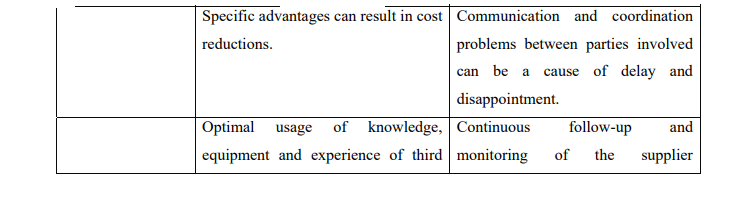

There are two different types of outsourcing namely :

- turnkey integral and

- Partial outsourcing.

Turnkey outsourcing applies when the responsibility for the execution of the entire function (or activities) lies with the external supplier. This includes not only the execution of the activities but also the coordination of these activities. Partial outsourcing refers to the case in which only a part of an integrated function is outsourced.

3.7 Strategic phase

During the strategic phase three essential questions have to be answered:

The question relates to the objective of the firm with regard to its intent to outsource a certain activity.

what activities are considered for outsourcing.

what qualifications a supplier should be able to meet in order to qualify as a potential future partner for providing the activity concerned must be answered. The decision to outsource should support and enable the company’s overall strategy. The motives that are cited most are:

1. Focus on core competence.

2. Focus on cost efficiency/effectiveness and

3. Focus on service

This motives and that strategy of the outsourcing company should be aligned. These three motives and the outsourced activities should contribute to this strategy. The second question relates to what should be outsourced. Two important approaches are used to

answer this question;

- The transaction cost approach and

- The core competence approach.

The transaction cost approach is based on the idea of finding a governance structure aimed at arriving at the lowest cost possible for each transaction that is made. Transaction cost is defined as the costs that are associated with an exchange between two parties.

The assumptions of the transaction costs approach is that an exchange with an external party is based upon a contract. The (potential) costs associated with establishing, Monitoring and enforcing the contract, as well as the costs associated with managing the relationship with the external party, are all considered to be part of the transaction costs as well as the costs associated with the

transaction itself. Therefore all of these costs should be taken into account when deciding between make or buy options.

The level of the transaction costs depends upon three important factors. These factors are:

- frequency of the transaction,

- the level of the transaction specific investments and

- the external and internal uncertainty.

The frequency of the transaction is an important factor because the more frequently exchanges occur between partners, the higher the total costs that are involved. The level of the transaction specific investments also determines the level of transaction costs, because transaction-specific investments are investments that are more or less unique to a specific buyer-supplier relationship. Examples are investments in specific supplier tooling (such as molds and dies) by a large automotive manufacturer and the change costs involved when choosing a new accountant (internal staff need to get accustomed to the new accountant, the new accountant needs to be thoroughly briefed to get acquainted with the company etc.). These examples show that investments are made in assets as well as in human capital. Obviously the higher these investments are, the higher the transaction cost will be. The last factor that determines the transaction costs is the external and internal uncertainty. Uncertainty is a normal parameter in the decision-making process. It can be

defined as the inability to predict contingencies that may occur. The higher these uncertainties, the more slack a supplier wants to have in presenting his proposal and rates, and the more difficult it will be to make a fixed price or lump sum contract that deals with all uncertainties beforehand.

Therefore, the higher the level of uncertainty, the higher the transaction costs will be. The other approach on which an outsourcing decision can be based is the core competence approach. This theory is based, among others, on the work of Quinn and Hilmer (1994). The core competence approach is based on the assumption that, in order to create a sustainable competitive advantage, a company should concentrate its resources on a set of core competencies where it can achieve definable pre-eminence and provide a unique value for customers … (hence it should) strategically outsource all other activities’ (Quinn and Hilmer, 1994 p43). The important question

to be answered here is what are the firm’s core competence. Characteristics of core competence are;

- Skills or knowledge sets, not products or functions

- Flexible, long term platforms that are capable of adaptation

- Limited in number; generally two or three

- Unique sources of leverage in the value chain

- Areas where the company can dominate

- Elements important to the customer in the long run

- Embedded in the organization’s system

The competencies that satisfy these requirements are the core competencies and provide the firm with its long-term competitive advantage. These competencies must be closely protected and are not to be outsourced. All other activities should be procured from the markets if these markets are totally reliable and efficient.

Long and Vickers-Koch (1992) distinguish five categories of a firm’s activities, instead of two categories, core or non-core, (Quinn and Hilmer 1994). These five categories are;

- Cutting edge activities. The activities that determine the competitiveness of the organization from a long term perspective.

- Core activities. The activities that create the foundation and main process for the organization and its possible competitive advantages.

- Support activities. Those activities that are directly connected to the core competences.

- Separate activities. The activities that are part of the main process, but easily separated from that process and not related to the core competences.

- Peripheral activities. The activities that do not concern the main process.

Anorld (2000) also makes a further distinction in a firms activities. He distinguishes between:

- Company core activities. Activities that are directly to the core activities.

- Close-core activities. The activities that are directly related to the core activities.

- Core distinct activities. The supporting activities.

- Disposable activities. Activities with general availability.

Both studies imply that the outsourcing decision framework based upon the work of Quinn and Hilmer (1994) needs adjustment. Anold (2000) has developed a general model for whom the function should be outsourced. After the decision to outsource has it is essential that the right supplier is chosen. A suppler has to be selected who has the necessary technical and managerial capabilities to deliver the expected and required level of performance. Also the supplier should be able to understand and be committed to these requirements.

The supplier selection process is key to the success of the buyer-supplier relationship. Companies that make extensive use of supplier selection and monitoring practices in supplier partnership seem to be more successful than the companies. An adequate supplier selection model is crucial for the success of the outsourcing decision.

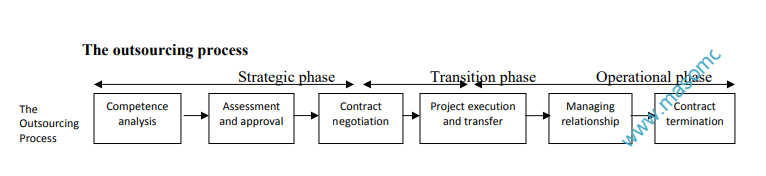

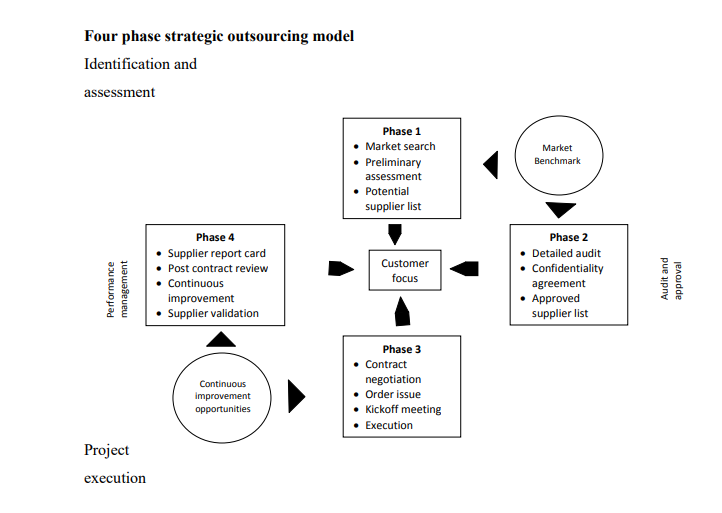

Momme and Hvolby (2002) present a four-phase model (figure below). This model gives guidance on how to identify, evaluate and select outsourcing candidates and therefore is an appropriate tool to use in the strategic phase . it also gives a brief guidance for the transition (phase 2 and 3) and the operational phase (phase 4), but needs to be elaborated for that purpose.

After the strategic phase in which the outsourced activities and supplier have been identified, the transmission phase starts. The transition consists of the contract negotiation and the project execution and transfer. The most important issue in the contract negotiation in an outsourcing agreement is often the start of a long term relationship, so not only the contractual issues should be

dealt with but the people issues and the importance of a sound and cooperative relationship should be covered as well.

The contract is the legal basis for the relationship and is therefore the key document in the outsourcing process. It allows both organizations to maximize the rewards of the relationship, while minimizing the risk. This makes the outsourcing contact key success factor for the establishment of a strategic outsourcing relationship.

The contract and the type of contract should reflect the business plan (the goal of the cooperation) the two parties have and should be seasonable for both parties. Performance management. There are different types of contracts. The type chosen depends on the characteristics and the scope of the contract and the functions or activities that are outsourced. After the transition phase has successfully ended, the operational phase of the outsourcing process starts. This operational phase consists of two processes namely:

- Managing the relationship and

- Contract termination.

Managing the buyer-supplier relationship management is one of the, if not the critical stage in the outsourcing relationship. Achieving the goals of the outsourcing relationship is impossible without close cooperation. When the relationship is not properly managed the conditions for close cooperation will not be present and the outcome of the outsourcing relationship will be far from optimal. The true value of outsourcing comes after the relationship has had time to develop and additional synergies have emerged. Creating sustaining, long relationship with a supplier is exciting: it’s where the win-win is really beginning to show.

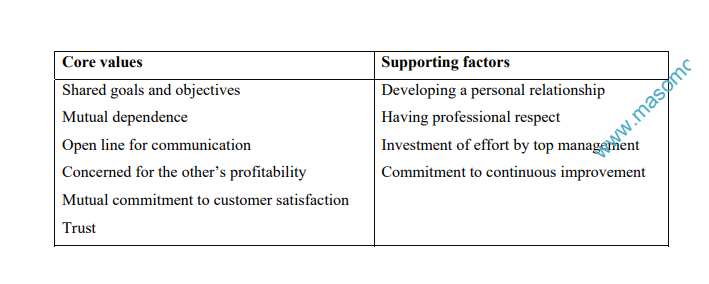

Many researchers have written on the characteristics of a successful buyer-supplier relationship.

The top five include

- the factors trust,

- flexibility,

- team approach,

- shared objectives and

- open communication.

The factors found by McQuiston to be core to a successful outsourcing relationship are presented in the table below.