Here we shall consider the methods of using derivatives -forwards, futures and options contracts and money market hedges.

Forward contracts

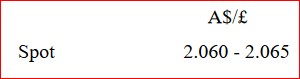

Forward foreign exchange contracts are a binding agreement between two parties to exchange an agreed amount of currency on a future date at an agreed fixed exchange rate. The exchange rate is fixed at the date the contract is entered into. Forward contracts are binding and must be executed by both parties. As we saw in the previous unit, they are not exchange regulated and one problem of this is that one of the parties might default. However, they do not -like futures contracts -come in standard sizes and have fixed delivery dates. Rather, they are over the counter (OTC) instruments-in which the contract can be tailor made to suit the needs of the parties and delivery dates can range from a few days to upwards of several years. In most cases, forward contracts have a fixed settlement date. This is appropriate where the cash transaction being hedged will take place on the same day that the forward contract is settled. However, there is no guarantee that the two days will tally -for example, a customer may be late paying -in which case the fixed settlement date is less than optimal. An alternative, to provide flexibility, is an “option date forward contract”. This offers a choice of dates on which the user can exercise the contract, although there is a higher premium payable on the contract for such an additional benefit. The purpose of a forward exchange rate contract is to purchase currency at a future date at a price fixed today. As such, it provides a complete hedge against adverse exchange rate movements in the intervening period. Consider the following example. A UK company needs to pay A$1 m to a Australian company in three months’ time. The current spot and forward exchange rates for sterling are as follows:

3 months forward 4 -3 cents pm

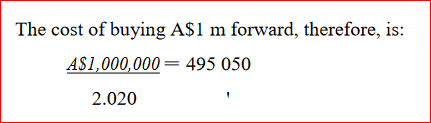

What would be the cost in sterling to the UK company if it enters into a forward contract to purchase the A$1 m needed? Note the way in which the rates are quoted. The spot rate spread shows the sell and buy prices -the banks will sell A$s for sterling at the rate of A$2.060/£, and buy A$s in return for sterling at the rate of A$2.065/£. The forward rate is quoted in terms of the premium (“pm”) in cents which the Australian dollar is to sterling in the future. If the currency is at a premium, it is strengthening and the A$ will buy more pounds forward than it will spot or, conversely, the pound will buy less A$ forward than it will spot. (If the quoted forward rate had been, say, “3 cents dis” this would indicate a weakening of the currency.)To calculate the cost of the forward contract, we need to convert the forward rate premium into an exchange rate. Because it is a premium, we need to subtract the amount from the spot to give the following sell/buy forward rates:(2.060 -0.04) -(2.065 -0.03) = 2.020 -2.035 A$/£

Whilst we have said that forward contracts are binding, they can be closed out by entering into an opposite contract to sell the currency -either at the spot rate or through a different forward rate. Partial close-outs can also be arranged where, for example, the full amount of the forward contract is not required. However, these arrangements are costly and, hence, rare.

Currency swaps

In general, a swap relates to an exchange of cashflows between two parties -as we saw in relation to interest rate swaps in the previous unit. Thus, currency swaps relate to an exchange of cashflows in different currencies between two parties. They are agreements to exchange both a principal sum and the interest payments on it in different currencies for a stated period. Each party transfers the principal and then pays interest to the other on the principal received. Swaps are arranged, through banks, to suit the needs of the parties involved. The two key issues in setting up a currency swap are:

- The exchange rate to be used; and

- Whether the exchange of principal is to take place at both commencement and maturity, or only on maturity. The following example illustrates the general principles.

A German company is seeking to invest £20m in the UK and has been quoted an interest rate of 8% on sterling in London, whereas the equivalent loan in Euros is quoted at 7% fixed interest in Frankfurt. At the same time, a UK company wants to invest an equivalent amount in its German subsidiary and has been quoted an interest rate of 7.5% to raise a loan denominated in Euros on the Frankfurt Exchange. It could, however, raise the £20m in sterling in London at 5% fixed interest. In the absence of a swap, each company would have to accept the quoted terms for its loan denominated in the foreign currency. This would result in both companies paying a higher rate than would apply if the loan was raised in their domestic currency. A swap agreement would involve each company taking out the loan in its own domestic currency and then exchanging the principals. Each company would pay the interest on the principal received -i.e. the other company’s loan -and at the end of the loan period, the principals would be swapped back. The exchange rate to be applied is clearly crucial. If we assume that this is agreed as €1.25 = £1, the swap would be conducted as follows.

- The UK Company borrows £20m in England at an interest rate of 5% pa. It then swaps the principal of £20m for €25m (at the agreed exchange rate) with the German company. The German company pays the interest payments on the £20m loan (at 5% interest) to the UK Company, which then pays the bank. At the end of the loan period, the principal of €25m is swapped back for the £20m with the German company.

- The German company borrows €25m in Frankfurt at an interest rate of 7% pa. It then swaps this principal with the UK Company which pays the interest payments on the loan (at 7% interest) to the German company, which then pays its bank. At the end of the loan period, the principal of £20m is swapped back for the€25m with the UK company

Currency Futures

A currency futures contract is an agreement to purchase or sell a standard quantity of foreign currency at a pre-determined date. As we saw previously, futures have standard quantities and delivery dates set by the exchange on which the contracts are traded. As we have also seen, the vast majority of these contracts are not delivered, but are closed out. The process of hedging exchange rate risk through the futures market is the same as we examined in relation to interest rate exposure in the previous unit. Thus, a UK company exporting to the USA and invoicing in US dollars, would need to hedge against a rise in the exchange rate (sterling strengthening relative to the dollar) in the period before payment is received. If we assume that payment is due in two months’ time, the exporter will need to sell dollars then in exchange for sterling. The strategy would be, therefore, to take out a three-month sterling futures contract and close it out in two months’ time -i.e. buy sterling futures now, hold them for two months and then sell them to cancel out the obligation to deliver the underlying currency. Any profit on the contract (the difference between the buying and selling prices) will offset any loss on the dollars received from an exchange rate rise over the period. We can illustrate the process in more detail by reference to the actions of a speculator who is anticipating a rise in the value of the $ against the pound. He will, therefore, take a position to sell sterling futures in anticipation that the future cost (in dollars) of buying the pounds necessary to meet the contract obligation will be less than the proceeds of the sale under the contract. If the current spot rate is $1.900/£ and December sterling futures are trading at $1.875/£, what will be the gain or loss on five sterling futures contracts if the spot rate in December is $1.800/£?(The standard size of sterling futures is £62,500.)

- Sale of five December contracts (each of which is for £62,500) at the agreed rate of $1.875/£ results in proceeds of:5 x £62,500 x $1.875 = $585,937.50

- Purchase of the equivalent amount in sterling in December at the spot rate of $1.8/£ results in an outlay of:5 x £62,500 x $1.8 = $562,500.

- The gain on the transaction is $23,437.50 or, converting this into pounds at the December spot rate, £13,020.The advantage for the speculator of using the futures contract compared to the alternative of buying sterling at the current spot rate is that he only needs to put down a small deposit (the margin account) as opposed to an “up front” investment of $593,750 (£312,500 x $1.9).

Hedging using futures and forwards contracts

We can also consider the difference between a hedge using forward contracts and a hedge using futures contracts. In December, a UK exporter invoices its US customer for $407,500 payable on 1 February. The exporter needs to hedge against a change in exchange rates whereby sterling becomes stronger relative to the dollar and he receives less pounds than now upon exchange of the dollars received in February. To hedge this exchange rate exposure, the company could take out either a forward contract or a futures contract. Which would be more appropriate given the following rates?

Currency Options

A currency option gives the holder the right, but not the obligation, to buy (in the case of a call option) or sell (a put option) a specified amount of currency at an agreed exchange rate (the exercise price) at a specific future date. The principles of currency options are the same as those discussed in the previous unit in respect of other types of option. Thus, using the options market to hedge exchange rate exposure sets a limit on the loss that can be made in the case of adverse movements in exchange rates, but also allows the holder to take advantage of favorable movements. The following example illustrates their use. At the beginning of July, a UK company purchased goods to the value of $300,000 from its US supplier on three months’ credit, payable at the end of September. The spot exchange rate is currently $1.95/£, and for the purposes of the example, we shall assume that it falls to $1.88/£ by the end of September, coinciding with the expiry of the option. Because the company needs to pay for the goods in dollars, it needs a strategy which enables it to sell pounds and buy dollars. The two choices are a long put or a short call. The short call, though, can only provide protection against exchange rate losses up to the cost of the premium, so the favored strategy would be a long put. (Check with the previous unit to ensure that you understand the various pay-off profiles for these different types of option.)