Economic Growth

Economic growth is an increase in activity in an economy. It refers only to the quantity of goods and services produced; it says nothing about the way in which they are produced.

Economic development

Economic development refers to social and technological progress. It implies a change in the way goods and services are produced, not merely an increase in production achieved using the old methods of production on a wider scale. Economic development typically

involves improvements in a variety of indicators such as literacy rates, life expectancy, and poverty rates.

Measures of Economic Wellbeing/Health

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

Economic health is often measured as the rate of change of gross domestic product (GDP). GDP can be defined in three ways, all of which are conceptually identical. First, it is equal to the total expenditures for all final goods and services produced within the country in a stipulated period of time (usually a 365-day year).

Second, it is equal to the sum of the value added at every stage of production (the intermediate stages) by all the industries within a country, plus taxes less subsidies on products, in the period.

Third, it is equal to the sum of the income generated by production in the country in the period i.e., compensation of employees, taxes on production and imports less subsidies, and gross operating surplus (or profits). The most common approach to measuring and quantifying

GDP is the expenditure method:

GDP = private consumption + gross investment + government spending + (exports − imports)

Gross national product (GNP) is sometimes used as an alternative measure to gross domestic product. GNP adds net foreign investment income, unlike GDP.

GNP = GDP + net foreign investment income

Put simply, GDP is concerned with the region in which income is generated. It is the market value of all the output produced in a nation in one year. GDP focuses on where the output is produced rather than who produced it. GDP measures all domestic production,

disregarding the producing entities’ nationalities.

In contrast, GNP is a measure of the value of the output produced by the “nationals” of a region. GNP focuses on who owns the production. For example, in the Kenya, GNP measures the value of output produced by Kenyan firms, regardless of where the firms are located.

Limitations of GDP as a Measure of Economic Health

Wealth distribution – GDP does not take disparity in incomes between the rich and poor into account. However, numerous Nobel-prize winning economists have disputed the importance of income inequality as a factor in improving long-term economic growth. In fact, short term increases in income inequality may even lead to long term decreases in income inequality.

Non-market transactions – GDP excludes activities that are not provided through the market, such as household production and volunteer or unpaid services. As a result, GDP is understated. Unpaid work conducted on Free and Open Source Software (such as Linux) contributes nothing to GDP, but it was estimated that it would have cost more than a billion US dollars for a commercial company to develop.

Underground economy – Official GDP estimates may not take into account the underground economy, in which transactions contributing to production, such as illegal trade and tax-avoiding activities, are unreported, causing GDP to be underestimated.

Non-monetary economy – GDP omits economies where no money comes into play at all, resulting in inaccurate or abnormally low GDP figures. For example, in countries with major business transactions occurring informally, portions of local economy are not easily registered. GDP also ignores subsistence production.

Quality of goods – People may buy cheap, low-durability goods over and over again, or they may buy high-durability goods less often. It is possible that the monetary value of the items sold in the first case is higher than that in the second case, in which case a higher GDP is simply the result of greater inefficiency and waste.

Quality improvements and inclusion of new products – By not adjusting for quality improvements and new products, GDP understates true economic growth. For instance, although computers today are less expensive and more powerful than computers from the past, GDP treats them as the same products by only accounting for the monetary value. The introduction of new products is also difficult to measure accurately and is not reflected in GDP despite the fact that it may increase the standard of living. For example, even the richest person from 1900 could not purchase standard products, such as antibiotics and cell phones that an average consumer can buy today, since such modern conveniences did not exist back then.

What is being produced – GDP counts work that produces no net change or that results from repairing harm. For example, rebuilding after a natural disaster or war may produce a considerable amount of economic activity and thus boost GDP. The economic value of health care is another classic example—it may raise GDP if many people are sick and they are receiving expensive treatment, but it is not a desirable situation.

Externalities – GDP ignores externalities such as damage to the environment. By counting goods which increase utility but not deducting or accounting for the negative effects of higher production, such as more pollution, GDP is overstating economic welfare.

Sustainability of growth – GDP does not measure the sustainability of growth. A country may achieve a temporarily high GDP by over-exploiting natural resources or by misallocating investment.

For example, the large deposits of phosphates gave the people of Nauru one of the highest per capita incomes on earth, but since 1989 their standard of living has declined sharply as the supply has run out. Oil-rich states can sustain high GDPs without industrializing, but this high level would no longer be sustainable if the oil runs out. Economies experiencing an economic bubble, such as a housing bubble or stock bubble, or a low private-saving rate tend to appear to grow faster owing to higher consumption, mortgaging their futures for present growth. Economic growth at the expense of environmental degradation can end up costing dearly to clean up; GDP does not account for this.

Alternative Measures of Economic Wellbeing

Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI)

GPI is a concept in welfare economics that has been suggested to replace gross domestic product (GDP) as a metric of economic growth. GPI is an attempt to measure whether a country’s growth, increased production of goods, and expanding services have actually resulted in the improvement of the welfare (or well-being) of the people in the country. GPI advocates claim that it can more reliably measure economic progress, as it distinguishes between worthwhile growth and uneconomic growth. The GDP vs the GPI is analogous to the difference between the gross profit of a company and the net profit; the Net Profit is the Gross Profit minus the costs incurred. Accordingly, the GPI will be zero if the financial costs financial gains in production of goods and services, all other factors being constant. Advocates of GPI assert that in some situations, expanded production facilities damage the health, culture, and welfare of people. Growth that was in excess of sustainable norms had to be considered to be uneconomic

The Human Development Index (HDI)

HDI is a summary measure of human development that is published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). HDI measures the average achievements in a country in three basic dimensions of human development:

- A long and healthy life, as measured by life expectancy at birth.

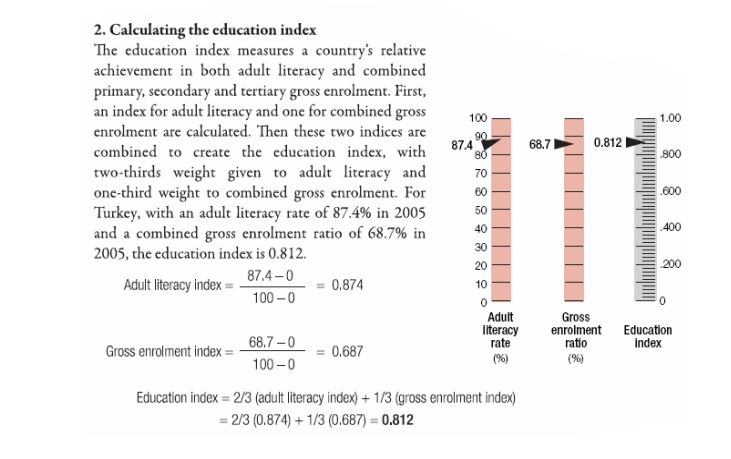

- Knowledge, as measured by the adult literacy rate (with two-thirds weight) and the combined primary, secondary and tertiary gross enrollment ratio (with onethird weight).

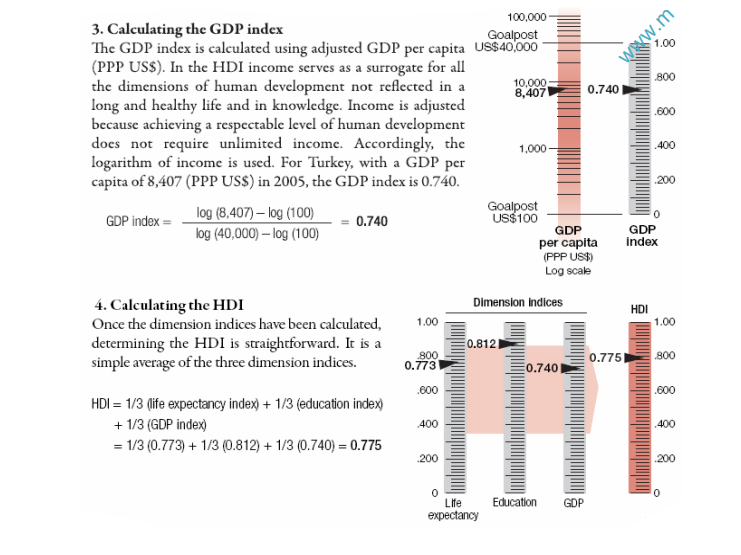

- A decent standard of living, as measured by GDP per capita in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms in US dollars.

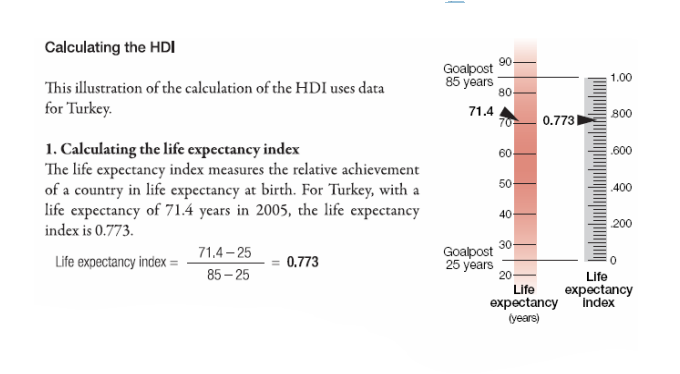

Before the HDI itself is calculated, an index is created for each of these dimensions. To calculate these indices—the life expectancy, education and GDP indices—minimum and maximum values (goalposts) are chosen for each underlying indicator. For example, in

the maximum and minimum values for life expectancy were 85 and 25 years, Adult literacy rate (%) 100 and 0, Combined gross enrolment ratio (%) 100 and 0, GDP per capita (US$) 40,000 and100 respectively. Performance in each dimension is expressed as a value between 0 and 1. The HDI is then calculated as a simple average of the dimension indices:

HDI = 1/3 (life expectancy index) + 1/3 (education index) + 1/3 (GDP index)

The Indicator Problem

When the term indicator is used in the following, it refers to data and ‘simple’ statistical composites (e.g. gross domestic product and life expectancy) which are recognized as analytic decision-making tools. Highly composite index-type indicators (e.g. human development index) are explicitly excluded here. The main problems can be stated as follows:

Proliferation of indicators– The sheer volume of development indicators and the lack of information on how similar indicators are related makes it difficult for analysts and decision

makers to use them.

Inconsistencies among indicators– Despite references to seemingly identical indicators, there exists differences in the definition, in the use of data sources, in the compilation method, in the periodicity etc., which lead to different numerical values.

Validity of indicators– Sources, definitions and compilation/ estimation methods are not always made explicit. The lack of adequate referencing and of technical notes deprives the user of making an informed quality assessment.

Separation of indicator development from basic data collection at country level Insufficient attention is given to improving the quality and comprehensiveness of basic data from which indicators are derived.

Overburdening of national statistical systems- Competing demands and poor overlap1 of internationally formulated indicator sets increase the reporting burden of national statistical agencies. Ad hoc requests by international agencies lead to ad hoc data collection, crowding out limited financial and human resources and, thus, interfering with regular national statistical programmes. Inefficient use of statistical resources- At present agencies does not share information coming from the country level optimally. There are potential efficiency gains by organizing better the flow of information.