Community health is a major field of study within the medical and clinical sciences which focuses on the maintenance, protection and improvement of the health status of population groups and communities as opposed to the health of individual patients. It is a distinct field of study that may be taught within a separate school of public health or environmental health.

It is a discipline which concerns itself with the study and improvement of the health characteristics of biological communities. While the term community can be broadly defined, community health tends to focus on geographical areas rather than people with shared characteristics. The health characteristics of a community are often examined using geographic information system (GIS) software and public health datasets. Some projects, such as InfoShare or GEOPROJ combine GIS with existing datasets, allowing the general public to examine the characteristics of any given community in participating countries.

Because ‘health III’ (broadly defined as well-being) is influenced by a wide array of socio-demographic characteristics, relevant variables range from the proportion of residents of a given age group to the overall life expectancy of the neighborhood/community. Medical interventions aimed at improving the health of a community range from improving access to medical care to public health communications campaigns. Recent research efforts have focused on how the built environment and socio-economic status affect health.

Community health may be studied within three broad categories:

- Primary healthcare which refers to interventions that focus on the individual or family such as hand-washing, immunization, circumcision, personal dietary choices, and lifestyle improvement.

- Secondary healthcare refers to those activities which focus on the environment such as draining puddles of water near the house, clearing bushes, and spraying insecticides to control vectors like mosquitoes.

- Tertiary healthcare on the other hand refers to those interventions that take place in a hospital setting, such as intravenous rehydration or surgery.

The success of community health programmes relies upon the transfer of information from health professionals to the general public using one-to-one or one to many communication (mass communication). The latest shift is towards health marketing.

Role of Community Health Workers

How Will CHWs

Affect Change?

The Initiative provides CHWs with creative strategies, materials, and tools for training, educating, and changing lifestyle behaviors so CHWs can be active promoters of health in their community.

Community health workers (CHWs) are lay members of the community who work either for pay or as volunteers in association with the local health care system in both urban and rural environments. CHWs usually share ethnicity, language, socioeconomic status, and life experiences with the community members they serve. They have been identified by many titles, such as community health advisors, lay health advocates, promotoras, outreach educators, community health representatives, peer health promoters, and peer health educators. CHWs offer interpretation and translation services, provide culturally appropriate health education and information, help people get the care they need, give informal counseling and guidance on health behaviors, advocate for individual and community health needs, and provide some direct services such as first aid and blood pressure screening.1

Since CHWs typically reside in the community they serve, they have the unique ability to bring information where it is needed most. They can reach community residents where they live, eat, play, work, and worship. CHWs are frontline agents of change, helping to reduce health disparities in underserved communities.

HRSA CHW National Workforce Study Findings1

CHW-specific work activities involved:

- Culturally appropriate health promotion and health education 82%

- Assistance in accessing medical services & programs 84%

- Assistance in accessing non-medical services & programs 72%

- “Translation” 36%

- Interpreting 34%

- Counseling 31%

- Mentoring 21%

- Social support 46%

- Transportation 36%

Related to work activities, employer-reported duties:

- Case management 45%

- Risk identification 41%

- Patient navigation 18%

- Direct services 37%

Among the many known outcomes of CHWs’ service are the following:

- Improved access to health care services.

- Increased health and screening.

- Better understanding between community members and the health and social service system.

- Enhanced communication between community members and health providers.

- Increased use of health care services.

- Improved adherence to health recommendations.

- Reduced need for emergency and specialty services.1

CHWs Take Action to Promote Heart Health in the Community

The Initiative’s health education materials are designed to be taught by CHWs, who are trained to use these materials to help community residents improve their quality of life by adopting heart healthy behaviors.

With the help of the Initiative, CHWs are able to:

- Help families understand their risk for developing heart disease.

- Help community members get appropriate screenings and referrals for health and social services.

- Track an individual’s progress toward meeting health goals.

- Hold workshops and group discussions to learn about ways the community can promote heart health.

- Teach people how to prepare heart healthy meals, get more physical activity, and stop smoking.

COMMUNITY HEALTH

The term “community health” refers to the health status of a defined group of people, or community, and the actions and conditions that protect and improve the health of the community. Those individuals who make up a community live in a somewhat localized area under the same general regulations, norms, values, and organizations. For example, the health status of the people living in a particular town, and the actions taken to protect and improve the health of these residents, would constitute community health. In the past, most individuals could be identified with a community in either a geographical or an organizational sense. Today, however, with expanding global economies, rapid transportation, and instant communication, communities alone no longer have the resources to control or look after all the needs of their residents or constituents. Thus the term “population health” has emerged. Population health differs from community health only in the scope of people it might address. People who are not organized or have no identity as a group or locality may constitute a population, but not necessarily a community. Women over fifty, adolescents, adults twenty-five to forty-four years of age, seniors living in public housing, prisoners, and blue-collar workers are all examples of populations. As noted in these examples, a population could be a segment of a community, a category of people in several communities of a region, or workers in various industries. The health status of these populations and the actions and conditions needed to protect and improve the health of a population constitute population health.

The actions and conditions that protect and improve community or population health can be organized into three areas: health promotion, health protection, and health services. This breakdown emphasizes the collaborative efforts of various public and private sectors in relation to community health. Figure 1 shows the interaction of the various public and private sectors that constitute the practice of community health.

Health promotion may be defined as any combination of educational and social efforts designed to help people take greater control of and improve their health. Health protection and health services differ from health promotion in the nature or timing of the actions taken. Health protection and services include the implementing of laws, rules, or policies approved in a community as a result of health promotion or legislation. An example of health protection would be a law to restrict the sale of hand guns, while an example of health services would be a policy offering free flu shots for the elderly by a local health department. Both of these actions could be the result of health promotion efforts such as a letter writing campaign or members of a community lobbying their board of health.

FOUNDATIONS OF COMMUNITY HEALTH

The foundations of community health include the history of community health practice, factors that affect community and population health, and the tools of community health practice. These tools include epidemiology, community organizing, and health promotion and disease prevention planning, management, and evaluation.

History of Community Health Practice. In all likelihood, the earliest community health practices went unrecorded. Recorded evidence of concern about health is found as early as 25,000 b.c.e., in Spain, where cave walls included murals of physical deformities. Besides these cave carvings and drawings, the earliest records of community health practice were those of the Chinese, Egyptians, and Babylonians. As early as the twenty-first century b.c.e., the Chinese dug wells for drinking.

Figure 1

Between the eleventh and second centuriesb.c.e., records show that the Chinese were concerned about draining rainwater, protecting their drinking water, killing rats, preventing rabies, and building latrines. In addition to these environmental concerns, many writings from 770 b.c.e. to the present mention personal hygiene, lifestyle, and preventive medical practices. Included in these works are statements by Confucius (551–479 b.c.e.) such as “Putrid fish … food with unusual colors… foods with odd tastes … food not well cooked is not to be eaten.” Archeological findings from the Nile river region as early as 2000 b.c.e., indicate that the Egyptians also had environment health concerns with rain and waste water. In 1900 b.c.e., Hammurabi, the king of Babylon, prepared his code of conduct that included laws pertaining to physicians and health practices.

During the years of the classical cultures (500 b.c.e.–500 c.e.), there is evidence that the Greeks were interested in men’s physical strength and skill, and in the practice of community sanitation. The Romans built upon the Greek’s engineering and built aqueducts that could transport water many miles. Remains of these aqueducts still exist. The Romans did little to advance medical thinking, but the hospital did emerge from their culture.

In the Middle Ages (500–1500 c.e.), health problems were considered to have both spiritual causes and spiritual solutions. The failure to account for the role of physical and biological factors led to epidemics of leprosy, the plague, and other communicable diseases. The worst of these, the plague epidemic of the fourteenth century, also known as the Black Death, killed 25 million people in Europe alone. During the Renaissance (1500–1700 c.e.), there was a growing belief that diseases were caused by environmental, not spiritual, factors. It was also a time when observations of the sick provided more accurate descriptions of the symptoms and outcomes of diseases. Yet epidemics were still rampant.

The eighteenth century was characterized by industrial growth, but workplaces were unsafe and living conditions in general were unhealthful. At the end of the century several important events took place. In 1796 Dr. Edward Jenner successfully demonstrated the process of vaccination for smallpox. And, in 1798, in response to the continuing epidemics and other health problems in the United States, the Marine Hospital Service (the forerunner to the U.S. Public Health Service) was formed.

The first half of the nineteenth century saw few advances in community health practice. Poor living conditions and epidemics were still concerns, but better agricultural methods led to improved nutrition. The year 1850 marks the beginning of the modern era of public health in the United States. It was that year that Lemuel Shattuck drew up a health report for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts that outlined the public health needs of the state. This came just prior to the work of Dr. John Snow, who removed the handle of the Broad Street pump drinking well in London, England, in 1854, to abate the cholera epidemic. The second half of the nineteenth century also included the proposal of Louis Pasteur of France in 1859 of the germ theory, and German scientist Robert Koch’s work in the last quarter of the century showing that a particular microbe, and no other, causes a particular disease. The period from 1875 to 1900 has come to be known as the bacteriological era of public health.

The twentieth century can be divided into several different periods. The years between 1900 and 1960 are known as the health resources development era. This period is marked by the growth of health care facilities and providers. The early years of the period saw the birth of the first voluntary health agencies: the National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis (now the American Lung Association) was founded in 1904 and the American Cancer Society in 1913. The government’s major involvement in social issues began with the Social Security Act of 1935. The two world wars accelerated medical discoveries, including the development of penicillin. In 1946, Congress passed the National Hospital Survey and Construction Act (Hill-Burton Act) to improve the distribution and enhance the quality of hospitals.

The social engineering era (1960–1975) included the passage of amendments to the Social Security Act that set up Medicare (payment of medical bills for the elderly and certain people with disabilities) and Medicaid (payment of medical bills for the poor). The final period of the twentieth century is the health promotion era (1974–1999). During this period it was recognized that the greatest potential for improving the health of communities and populations was not through health care but through health promotion and disease prevention programs. To move in this direction, the U.S. government created its “blueprint for health” a set of health goals and objectives for the nation. The first set was published in 1980 and titled Promoting Health/Preventing Disease: Objectives for the Nation. Progress toward the objectives has been assessed on a regular basis, and new goals and objectives created in volumes titled Healthy People 2000, and Healthy People 2010. Other countries, and many states, provinces, and even communities, have developed similar goals and targets to guide community health.

Factors that Affect Community and Population Health. There are four categories of factors that affect the health of a community or population. Because these factors will vary in separate communities, the health status of individual communities will be different. The factors that are included in each category, and an example of each factor, are noted here.

Figure 2

- Physical factors—geography (parasitic diseases), environment (availability of natural resources), community size (overcrowding), and industrial development (pollution).

- Social and cultural factors—beliefs, traditions, and prejudices (smoking in public places, availability of ethnic foods, racial disparities), economy (employee health care benefits), politics (government participation), religion (beliefs about medical treatment), social norms (drinking on a college campus), and socioeconomic status (number of people below poverty level).

- Community organization—available health agencies (local health department, voluntary health agencies), and the ability to organize to problem solve (lobby city council).

- Individual behavior—personal behavior (health-enhancing behaviors like exercising, getting immunized, and recycling wastes; see Figure 2).

Three Tools of Community Health Practice. Much of the work of community health revolves around three basic tools: epidemiology, community organizing, and health education. Though each of these is discussed in greater length elsewhere in the encyclopedia, they are mentioned here to emphasize their importance to community and population practice. Judith Mausner and Shira Kramer have defined epidemiology as the study of the distribution and determinants of diseases and injuries in human populations. Such data are recorded as number of cases or as rates (number per 1,000 or 100,000). Epidemiological data are to community health workers as biological measurements are to a physician. Epidemiology has sometimes been referred to as population medicine. Herbert Rubin and Irene Rubin have defined community organizing as bringing people together to combat shared problems and increase their say about decisions that affect their lives. For example, communities may organize to help control violence in a neighborhood. Health education involves health promotion and disease prevention (HP/DP) programming, a process by which a variety of interventions are planned, implemented, and evaluated for the purpose of improving or maintaining the health of a community or population. A smoking cessation program for a company’s employees, a stress management class for church members, or a community-wide safety belt campaign are examples of HP/DP programming.

COMMUNITY AND POPULATION HEALTH THROUGH THE LIFE SPAN

In community health practice, it is common to study populations by age group and by circumstance because of the health problems that are common to each group. These groupings include mothers, infants (less than one year old), and children (ages 1–14); adolescents and young adults (ages 15–24); adults (ages 25–64); and older adults or seniors (65 years and older).

Maternal, infant, and child (MIC) health encompasses the health of women of childbearing age from prepregnancy through pregnancy, labor, delivery, and the postpartum period, and the health of a child prior to birth through adolescence. MIC health statistical data are regarded as important indicators of the status of community and population health. Unplanned pregnancies, lack of prenatal care, maternal drug use, low immunization rates, high rates of infectious diseases, and lack of access to health care for this population indicate a poor community health infrastructure. Early intervention with educational programs and preventive medical services for women, infants, and children can enhance health in later years and reduce the necessity to provide more costly medical and/or social assistance later in their life.

Maternal health issues include family planning, early and continuous prenatal care, and abortion. Family planning is defined as the process of determining and achieving a preferred number and spacing of children. A major concern is the more than 1 million U.S. teenagers who become pregnant each year. About 85 percent of these pregnancies are unintended. Also a part of family planning and MIC is appropriate prenatal care, which includes health education, risk assessment, and medical services that begin before the pregnancy and continue through birth. Prenatal care can reduce the chances of a low-birthweight infant, and the poor health outcomes and costs associated with it. A controversial way of dealing with unintended or unwanted pregnancies is with abortion. Abortion has been legal in the United States since 1973 when the Supreme Court ruled in Roe v. Wade that women have a constitutionally protected right to have an abortion in the early stages of pregnancy. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately 1.6 million legal abortions were being performed in the United States each year during the late 1990s.

Infant and child health is the result of parent health behavior during pregnancy, prenatal care, and the care provided after birth. Critical concerns of infant and childhood morbidity and mortality include proper immunization, unintentional injuries, and child abuse and neglect. Though numerous programs in the United States address MIC health concerns, one that has been particularly successful has been the Special Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants, and Children, known as the WIC program. This program, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, provides food, nutritional counseling, and access to health services for low-income women, infants, and children. Late-twentieth-century figures indicate that the WIC program serves more than seven million mothers and children per month, and saves approximately three dollars for each tax dollar spent.

The health of the adolescent and young adult population sets the stage for the rest of adult life. This is a period during which most people complete their physical growth, marry and start families, begin a career, and enjoy increased freedom and decision making. It is also a time in life in which many beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors are adopted and consolidated. Health issues that are particularly associated with this population are unintended injuries; use and abuse of alcohol, tobacco, and drugs; and sexual risk taking. There are no easy, simple, or immediate solutions to reducing or eliminating these problems. However, in communities where interventions have been successful, they have been comprehensive and communitywide in scope and sustained over long periods of time.

The adult population represents about half of the U.S. population. The health problems associated with this population can often be traced to the consequences of poor socioeconomic conditions and poor health behavior during earlier years. To assist community health workers, this population has been subdivided into two groups: ages twenty-five to forty-four and ages forty-five to sixty-four. For the younger of these two subgroups, unintentional injuries, HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection, and cancer are the leading causes of death. For the older group, noncommunicable health problems dominate the list of killers, headed by cancer and heart disease, which account for almost two-thirds of all deaths. For most individuals, however, these years of life are the healthiest. The key to community health interventions for this population has been to stress the quality of life gained by good health, rather than merely the added years of life.

The senior population of the United States has grown steadily over the years, and will continue to grow well into the twenty-first century. In 1900 only one in twenty-five Americans was over the age of sixty-five, in 1995 it was one in seven, and by 2030 it is expected to be one in five. Such growth in this population will create new economic, social, and health concerns, especially as the baby boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964) reach their senior years. From a community and population health perspective, greater attention will need to be placed on the increased demands for affordable housing, accessible transportation, personal care created by functional limitations, and all segments of health care including adult day care and respite care. Though many communities have suitable interventions in place to deal with the issues of seniors (including meal services like congregate meals at senior centers, and Meals-on-Wheels), the demands will increase in all communities.

HEALTH PROMOTION

The three strategies by which community health practice is carried out are health promotion, health protection, and the provision of health services and other resources. Figure 3 presents a representation of these strategies, their processes, their objectives, and anticipated benefits for a community or population.

As noted earlier, health promotion includes educational, social, and environmental supports for individual, organizational, and community action. It seeks to activate local organizations and groups or individuals to make changes in behavior (lifestyle, selfcare, mutual aid, participation in community or political action) or in rules or policies that influence health. Community health promotion lies in the areas in which the spheres of health action, as shown in Figure 1, overlap.

Two areas in which communities employ health promotion strategies are mental and social health, and recreation and fitness. Though both of these health concerns seem to be problems of individuals, a health concern becomes a community or population health concern when it is amenable to amelioration through the collective actions noted above. Action to deal with these concerns begins with a community assessment, which should identify the factors that influence the health of the subpopulations and the needs of these populations. In the case of mental and social health, the need will surface at the three levels of prevention: primary prevention (measures that forestall the onset of illness), secondary prevention (measures that lead to an early diagnosis and prompt treatment), and tertiary prevention (measures aimed at rehabilitation following significant pathogenesis).

Primary prevention activities for mental and social health could include personal stress management strategies such as exercise and meditation, or school and workplace educational classes to enhance the mental health of students and workers. A secondary prevention strategy could include the staffing of a crisis hot line by local organizations such a health department or mental health center. Tertiary prevention might take the form of the local medical and mental health specialists and health care facilities providing individual and group counseling, or inpatient psychiatric treatment and rehabilitation. All of these prevention strategies can contribute to a communitywide effort to improve the mental and social health of the community or population. During and after the implementation of the strategies, appropriate evaluation will indicate which strategies work and which need to be discontinued or reworked.

As with mental and social health promotion, community recreation and fitness needs should be derived via community assessment. The community or population enhances the quality of life and provides alternatives to the use of drugs and alcohol as leisure pursuits by having organized recreational programs that meet the social, creative, aesthetic, communicative, learning, and physical needs of its members. Such programs can provide a variety of benefits that can contribute to the mental, social, and physical health of the community, and can be provided or supported by schools, workplaces, public and private recreation and fitness organizations, commercial and semipublic recreation, and commercial entertainment. As with all health-promotion programming, appropriate evaluation helps to monitor progress, appropriate implementation of plans, and outcomes achieved.

HEALTH PROTECTION

Community and population health protection revolve around environmental health and safety. Community health personnel work to identify environmental risks and problems so they can take the necessary actions to protect the community or population. Such protective measures include the control of unintentional and intentional injuries; the control of vectors; the assurance that the air, water, and food are safe to consume; the proper disposal of wastes; and the safety of residential, occupational, and other environments. These protective measures are often the result of educational programs, including self-defense classes; policy development, such as the Safe Drinking Water Act or the Clean Air Act; environmental changes,

Figure 3

such as restricting access to dangerous areas; and community planning, as in the case of preparing for natural disasters or upgrading water purification systems.

HEALTH SERVICES AND OTHER RESOURCES

The organization and deployment of the services and resources necessary to plan, implement, and evaluate community and population health strategies constitutes the third general strategy in community and population health. Today’s communities differ from those of the past in several ways. Even though community members are better educated, more mobile, and more independent than in the past, communities are less autonomous and more dependent on those outside the community for support. The organizations that can assist communities and populations are classified into governmental, quasi-governmental, and nongovernmental groups. Such organizations can also be classified by the different levels (world, national, state/province, and local) at which they operate.

Governmental health agencies are funded primarily by tax dollars, managed by government officials, and have specific responsibilities that are outlined by the governmental bodies that oversee them. Governmental health agencies include: the World Health Organization (WHO), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the various state health departments, and the over three thousand local health departments throughout the country. It is at the local level that direct health services and resources reach people.

Quasi-governmental health organizations have some official responsibilities, but they also operate in part like voluntary health organizations. They may receive some government funding, yet they operate independently of government supervision. An example of such a community health organization is the American Red Cross (ARC). The ARC has certain official responsibilities placed on it by the federal government, but is funded by voluntary contributions. The official duties of the ARC include acting as the official representative of the U.S. government during natural disasters and serving as the liaison between members of the armed forces and their families during emergencies. In addition to these official responsibilities, the ARC engages in many nongovernmental services such as blood drives and safety services classes like first aid and water safety instruction.

Nongovernmental health agencies are funded primarily by private donations or, in some cases, by membership dues. The thousands of these organizations all have one thing in common: They

Figure 4

arose because there was an unmet need for them. Included in this group are voluntary health agencies; professional health organizations and associations; philanthropic foundations; and service, social, and religious organizations.

Voluntary health organizations are usually founded by one or more concerned citizens who felt that a specific health need was not being met by existing government agencies. Examples include the American Cancer Society, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), and the March of Dimes. Voluntary health agencies share three basic objectives: to raise money from various sources for research, to provide education, and to provide services to afflicted individuals and families.

Professional health organizations and associations are comprised of health professionals. Their mission is to promote high standards of professional practice, thereby improving the health of the community. These organizations are funded primarily by membership dues. Examples include the American Public Health Association, the British Medical Association, the Canadian Nurses Association, and the Society for Public Health Education.

Philanthropic foundations have made significant contributions to community and population health in the United States and throughout the world. These foundations support community health by funding programs or research on the prevention, control, and treatment of many diseases, and by providing services to deal with other health problems. Examples of such foundations are the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, and the W. K. Kellogg Foundation.

Service, social, and religious organizations have also played a part in community and population health by raising money and funding health-related programs. For example, the Lions Clubs has worked to help prevent blindness, Shriners have helped to provide free medical care through their hospitals, and many religious organizations have worked to feed, clothe, and provide shelter for those in need.

The health services and resources provided through the organizations discussed above are focused at the community level. However, a significant portion of the resources are aimed at personal health care. Figure 4 presents the spectrum of health care delivery in the United States. Some refer to this as the U.S. health care system; others would debate whether any system really exists, referring to this network of services as an array of informal communications between health care providers and health facilities. The spectrum of care begins with public health (or population-based) practice, which is a significant component of community and population health practice. It then moves to four different levels of medical practice. The first level is primary, or front-line or first-contact, care. This involves the medical diagnosis and treatment of most symptoms not requiring a specialist or hospital. Secondary medical care gives specialized attention and ongoing management for both common and less frequently encountered medical conditions. Tertiary medical care provides even more highly specialized and technologically sophisticated medical and surgical care, including the long-term care often associated with rehabilitation. The final level of practice in the spectrum is continuing care, which includes longterm, chronic, and personal care.

What is Primary Health Care (PHC)?

Primary health care (PHC) is essential health care made universally accessible to individuals and acceptable to them, through full participation and at a cost the community and country can afford. It is an approach to health beyond the traditional health care system that focuses on health equity-producing social policy. Primary health-care (PHC) has basic essential elements and objectives that help to attain better health services for all.

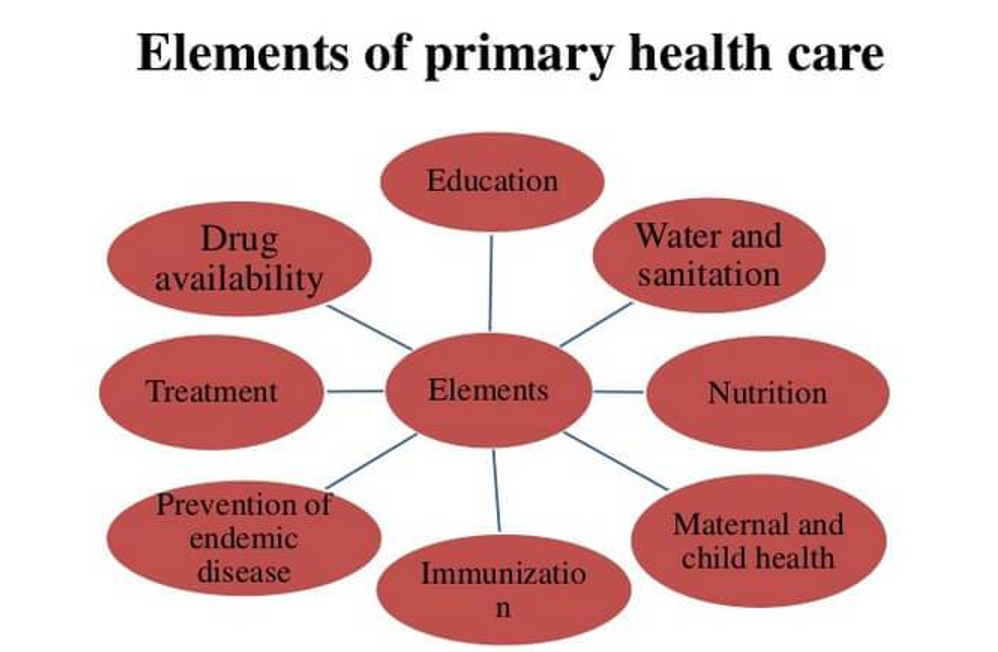

Primary health care elements

Essential Elements of Primary Health Care (PHC):

There are 8 elements of primary-health care (PHC). That listed below-

- E– Education concerning prevailing health problems and the methods of identifying, preventing and controlling them.

- L– Locally endemic disease prevention and control.

- E– Expanded programme of immunization against major infectious diseases.

- M– Maternal and child health care including family planning.

- E– Essential drugs arrangement.

- N– Nutritional food supplement, an adequate supply of safe and basic nutrition.

- T– Treatment of communicable and non-communicable disease and promotion of mental health.

- S– Safe water and sanitation.

Extended Elements in 21st Century:

- Expended options of immunizations.

- Reproductive health needs.

- Provision of essential technologies for health.

- Health promotion.

- Prevention and control of non-communicable diseases.

- Food safety and provision of selected food supplements.

Principles of Primary Health Care (PHC):

Behind these elements lies a series of basic objectives that should be formulated in national policies in order to launch and sustain primary health-care (PHC) as part of a comprehensive health system and coordination with other sectors.

- Improvement in the level of health care of the community.

- Favorable population growth structure.

- Reduction in the prevalence of preventable, communicable and other disease.

- Reduction in morbidity and mortality rates especially among infants and children.

- Extension of essential health services with priority given to the undeserved sectors.

- Improvement in basic sanitation.

- Development of the capability of the community aimed at self-reliance.

- Maximizing the contribution of the other sectors for the social and economic development of the community.

- Equitable distribution of health care– according to this principle, primary care and other services to meet the main health problems in a community must be provided equally to all individuals irrespective of their gender, age, and caste, urban/rural and social class.

- Community participation-comprehensive healthcare relies on adequate number and distribution of trained physicians, nurses, allied health professions, community health workers and others working as a health team and supported at the local and referral levels.

- Multi-sectional approach-recognition that health cannot be improved by intervention within just the formal health sector; other sectors are equally important in promoting the health and self- reliance of communities.

- Use of appropriate technology- medical technology should be provided that accessible, affordable, feasible and culturally acceptable to the community.

Sources of Health Information

- Census

2. Registration of Vital Events

3. Sample Registration System (SRS)

4. Notification of Diseases

5.Hospital Records

6.Disease Registers

7.Record Linkage

8.Epidemiological Surveillance

9.Other Health Service Records

10.Environmental Health Data

11.Health Manpower Statistics

12.Population Surveys

13. Other routine statistics related to health

14. Non-quantifiable information

Census

Census is taken in most countries of the world at regular intervals

Definition of Census (UN): ‘The total process of collecting, compiling and publishing demographic, economic and social data pertaining at a specified time or times, to ALL persons in a country or delimited territory’.

It is massive undertaking to contact every member of the population in a given time and collect a variety of information

It needs

• Massive preparation and

• Several years to analyze the results after census is taken

• This is the main problem of census as a data source i.e. that the results are not available quickly

Registration of Vital Events.

Definition (UN): ‘legal registration, statistical recording and reporting of the occurrence of and the collection, compilation, presentation, analysis and distribution of statistics pertaining to vital events’

Vital events include:

- Live births

- Deaths

- Fetal deaths

- Marriage

- Divorce

- Adoptions

- Legitimations

- Recognitions

- Annulments and

- Legal separations

3. Sample Registration System (SRS)

The civil registration system has a lot to be improved and would require a huge effort and time. A need for having an alternate source of such information was felt. SRS aims to provide reliable estimates of birth and death rates for the States and also at All India level. Following features of SRS ensure the completeness of vital events reporting:

1. A representative sample of the population is covered and NOT the WHOLE population

2. It is based on Dual – record system:

First a baseline survey of sampled units is done

This is followed by continuous enumeration of vital events of the areas by an enumerator (who is a volunteer from the community)

Independent retrospective 6-monthly surveys are done for recording births and deaths which occurred in the preceding 6 months and the number is matched with the one reported by the enumerator

Not only the numbers of vital events should match, it is also verified if the births and deaths reported by the enumerator are the same ones which the survey has found out. This is called as ‘Matching of events’ by the observer. At present, the Sample Registration System (SRS) provides reliable annual data on fertility and mortality at the state and national levels for rural and urban areas separately. In this survey, the sample units, villages in rural areas and urban blocks in urban areas are replaced once in ten years

Notification of Diseases

Disease notification is a practice of reporting the occurrence of a specific disease or health-related condition to the appropriate and designated authority. A notifiable disease is any disease that is required by law to be reported to government authorities. Effective notification allows the authorities to monitor the disease, and provides early warning of possible outbreaks

A notifiable disease is one for which regular and timely information regarding individual cases is considered necessary for the prevention and control of the disease.

Reasons for Declaring a Disease as Notifiable may be:

- It is of interest to national or international regulations or control programs

- Its National/ State/ District incidence

- Its severity (potential for rapid mortality)

- Its communicability/ Its potential to cause outbreaks

- Significant risk of international spread

- The socio-economic costs of its cases

- Its preventability

- Evidence that its pattern is changing

In other words, diseases which are considered to be serious menaces to public health are included in the list of notifiable diseases.

Disease Registers

A registry is basically a list of all the patients in the defined population who have a particular condition. It is different from ‘notification’ where the case is reported and is counted once.

A register requires that a permanent record be established that the cases be followed up and that basis statistical tabulation be prepared both on frequency and on survival. Hence mostly for chronic conditions.In addition the patients on a register are frequently be the subjects of special studies

• Morbidity registers are a valuable source of information such as the

duration of illness, case fatality and survival

Natural history of disease especially chronic diseases

There are two types of registries:

1. Hospital based:

It involves recording of information on the patients seen in a particular hospital. The primary purpose of hospital based registries is to contribute to patient care by providing readily accessible information on the patients, the treatment received and its results. The data is also used for clinical research and for epidemiological purposes.

The objectives of hospital based registry:

• Assess patient care

• Participate in clinical research to evaluate therapy

• Provide an idea of the patterns of cases

• Contribute to follow up of the patients

• Epidemiological research through case control studies

• Show time trends in the stage of diagnosis

• Help study the quality of care for the patients in the hospitals

2. Population-Based Registry:

A population-based disease registry contains and tracks records for people diagnosed with a specific type of disease who reside within a defined geographic region (i.e., a community, city, or state-wide)

The major concern of Population Based Registries is to calculate the incidence rates.

Population Based Registry systematically collects information on all reportable cases occurring in a geographically defined population from multiple sources.

The comparison and interpretation of population based incidence data support population-based actions aimed at reducing the burden in the community. The systematic ascertainment of incidence from multiple sources can provide an unbiased profile of the burden in the population and how it is changing over time.

Record Linkage

• Record linkage means bringing together information that relates to the same individual or family, from different data sources. In this way it is possible to construct chronological sequences of health events for individuals. The records may originate in different time or places.

Medical record linkage implies the gathering and maintenance of one file for each individual in a population, with records relating to his/her health.

The events commonly recorded are

- birth, marriage, death,

- hospital admission and discharge

- sickness absence from work,

- prophylactic procedures

- use of social services, etc.

Record linkage is a particularly suitable method of studying association between diseases; these associations may have etiological significance.

Epidemiological Surveillance

Surveillance systems are set up for select diseases under the respective control/eradication program as a procedural matter. The purpose of this surveillance is to keep an eye on the incidence, prevalence and changing pattern of the particular disease so as to adjust the control measures accordingly.

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY USES OF HEALTH INFORMATION

In most cases, your personal health information comes into the system from you or from other sources on your behalf, for the main reason of giving you health care. This is called the “primary purpose” (“primary” means “first”).

Once your health information is in the health care system, it is sometimes used for other “secondary” purposes. In general, you must be told about these secondary purposes, but sometimes you don’t have to be told, if the secondary purpose is reasonably connected to the primary purpose or is required by law.

For example, when you go to your doctor, you talk about a health problem you may have. Your doctor collects your information by writing it down in the paper file or entering into a computer file. Some of that information will be given to Medical Services Plan (“MSP”) so that the doctor can be paid for the visit. If you have to see a specialist, some of your personal health information might be sent to the specialist, and information about your visit to the specialist will be given to MSP so that the specialist can be paid. The information collected by the doctor and the specialist is collected for the primary purposes of giving you health care, and billing MSP.

Health information is also used for secondary purposes such as health system planning, management, quality control, public health monitoring, program evaluation, and research. Sometimes health information will be “de-identified” or “anonymized” before it is used for these secondary purposes.

There has in the past few years been some confusion about when identifiable personal health information can be used for secondary purposes. This is one of the reasons why the Ministry of Health Act was recently changed to let the Minister collect, use and disclose identifiable personal information for “stewardship purposes”, so that these uses and disclosures are no longer against the law.

The new law does not allow a person to limit access to their health records that are collected by the Ministry of Health Services from health authorities or other public bodies for a stewardship purpose.

For more discussion of this issue, see Laws that Apply to the Public Health System

Opinion of this new law

There are many people in BC who feel that making this change to the law was a good thing, because it is important and beneficial for government to be able to use personal health information for these types of secondary purposes, even when it still has a name or other identifier (such as a personal health number) attached to it.

Many other people are concerned that this law has significantly weakened privacy protection for personal health information in BC because it allows privacy and security to be ignored or minimized in favour of other values.

Emerging health issues: the widening challenge for population health promotion

SUMMARY

The spectrum of tasks for health promotion has widened since the Ottawa Charter was signed. In 1986, infectious diseases still seemed in retreat, the potential extent of HIV/AIDS was unrecognized, the Green Revolution was at its height and global poverty appeared less intractable. Global climate change had not yet emerged as a major threat to development and health. Most economists forecast continuous improvement, and chronic diseases were broadly anticipated as the next major health issue.

Today, although many broadly averaged measures of population health have improved, many of the determinants of global health have faltered. Many infectious diseases have emerged; others have unexpectedly reappeared. Reasons include urban crowding, environmental changes, altered sexual relations, intensified food production and increased mobility and trade. Foremost, however, is the persistence of poverty and the exacerbation of regional and global inequality.

Life expectancy has unexpectedly declined in several countries. Rather than being a faint echo from an earlier time of hardship, these declines could signify the future. Relatedly, the demographic and epidemiological transitions have faltered. In some regions, declining fertility has overshot that needed for optimal age structure, whereas elsewhere mortality increases have reduced population growth rates, despite continuing high fertility.

Few, if any, Millennium Development Goals (MDG), including those for health and sustainability, seem achievable. Policy-makers generally misunderstand the link between environmental sustainability (MDG #7) and health. Many health workers also fail to realize that social cohesion and sustainability—maintenance of the Earth’s ecological and geophysical systems—is a necessary basis for health.

In sum, these issues present an enormous challenge to health. Health promotion must address population health influences that transcend national boundaries and generations and engage with the development, human rights and environmental movements. The big task is to promote sustainable environmental and social conditions that bring enduring and equitable health gains.

INTRODUCTION

The Ottawa Charter (1986) was forged only 8 years after the historic Alma Ata meeting, which had declared Health for All by 2000. With hindsight, the goal of shaping a new and healthier world was already in jeopardy (Werner and Sanders, 1997). Perhaps, aware of this nascent weakening of the prospects for population health, the global health promotion community called for the revitalization of ambitious large-scale thinking. New strategies were devised to energize healthy individual and community behaviours, reflected in phrases such as ‘healthy choices should be easy choices’ and ‘healthy public policy’.

Nevertheless, over the ensuing two decades, the adverse social, economic and environmental trends that were already beginning to jeopardize, Health for All in 1986 have strengthened. Further, economic globalization, with increasingly powerful transnational companies shaping global consumer behaviours, has tended to make unhealthy choices the easier choices, including cigarettes, fast-food diets, high-sugar drinks, automated (no-effort) domestic technologies and others. These changes have occurred despite an increased understanding of the fundamental determinants of population health. Some of these foundations of health are at risk, and in some regions, hard-won health gains have recently been reversed. Recent attempts to re-focus attention on global public goods, such as in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), are weak in comparison to the scale of today’s problems.

There is an urgent strategic need for health promotion to engage with the international discourse on ‘sustainability’. To date much of the discussion and policy development addressing ‘sustainable development’ has treated the economy, livelihoods, energy supplies, urban infrastructure, food-producing ecosystems, wilderness conservation and convivial communal living as if they were ends in themselves: the goals of sustainability. Clearly, those are all major assets that we value. But their value inheres in their being the foundations upon which the health and survival of populations depend. The ultimate goal of sustainability is to ensure human well-being, health and survival. If our way of living, of managing the natural environment and of organizing economic and social relations between people, groups and cultures does not maintain the flows of food and materials, freshwater supplies, environmental stability and other prerequisites for health, then that is a non-sustainable state.

In this paper, we discuss several of the emerging health issues. Lacking space to be comprehensive, we focus upon infectious diseases, the decline in life expectancy in several regions, the increasingly ominous challenge of large-scale environmental change and how globalization, trade and economic policy relate to indices of public health. Other emerging health issues not discussed here also reflect major recent shifts in human ecology. They too pose great environmental or social risks to health. They include urbanization, population ageing, the breakdown of traditional culture and relations and the worldwide move towards a more affluent diet and its associated environmentally damaging food production methods (McMichael, 2005).

There are two fundamental causes for the selected emerging health risks. First, most important, is the global dominance of economic policies which accord primacy to market forces, liberalized trade and the associated intensification of material throughput at the expense of other aspects of social, environmental and personal well-being. For millions in the emerging global middle class, materialism and consumerism have increased at the expense of social relations and leisure time. The gap between rich and poor, both domestically and internationally, has increased substantially in recent decades (United Nations Development Program, 2005). Inequality between countries has weakened the United Nations and other global institutions. Foreign aid has declined, replaced by claims that market forces will reduce poverty and provide public goods, including health care and environmental stability.

The second fundamental threat to the improvement and maintenance of population health is the recent advent of unprecedented global environmental changes. The scale of the human enterprise (numbers, economic intensity, waste generation) is now such that we are collectively exceeding the capacity of the planet to supply, replenish and absorb. Stocks of accessible oil appear to be declining. Meanwhile, the global emissions of carbon dioxide from fossil fuel combustion, and of other greenhouse gases from industrial and agricultural activities, are rapidly and now dangerously altering the global climate. Worldwide, land degradation, fisheries depletion, freshwater shortages and biodiversity losses are all increasing. The human population, now exceeding 6500 million, continues to increase by over 70 million persons per annum. The number of chronically undernourished people (over 800 million) is again increasing, after gradual declines in the 1980s and early 1990s (Food and Agricultural Organization, 2005). Famines in Africa remain frequent, and 300 million undernourished people live in India alone. Meanwhile, hundreds of millions of people are overnourished and, particularly via obesity, will incur an increasing burden of chronic diseases, especially diabetes and heart disease.

The scale of these health risks is unprecedented. The global food crises of the 1960s were averted by the subsequent Green Revolution. Today, a broader-based revolution is required, not only to increase food production (again), but also to promote peace and international cooperation, slow climate change, ensure environmental protection, eliminate hunger and extreme poverty, quell resurgent infectious diseases and neutralize the obesogenic environment. This enormous population health task goes well beyond that envisaged by the MDGs.

It is, of course, difficult to get an accurate measure of these emerging risks to health. Some, such as climate change, future food sufficiency and the threat from weapons of mass destruction, may prove soluble. However, because of the inevitable time lag in understanding, evaluating and responding to these complex problems, the health promotion community should now take serious account of them. There is an expanding peer-reviewed literature on these several emerging problem, areas. To constrain health promotion by sidestepping them would be to risk being ‘penny wise but pound foolish’.

EMERGING AND RE-EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES

In the early 1970s, it was widely assumed that infectious diseases would continue to decline: sanitation, vaccines and antibiotics were at hand. The subsequent generalized upturn in infectious diseases was unexpected. Worldwide, at least 30 new and re-emerging infectious diseases have been recognized since 1975 (Weiss and McMichael, 2004). HIV/AIDS has become a serious pandemic. Several ‘old’ infectious diseases, including tuberculosis, malaria, cholera and dengue fever, have proven unexpectedly problematic, because of increased antimicrobial resistance, new ecological niches, weak public health services and activation of infectious agents (e.g. tuberculosis) in people whose immune system is weakened by AIDS. Diarrhoeal disease, acute respiratory infections and other infections continue to kill more than seven million infants and children annually (Bryce et al., 2005). Mortality rates among children are increasing in parts of sub-Saharan Africa (Horton, 2004).

The recent upturn in the range, burden and risk of infectious diseases reflects a general increase in opportunities for entry into the human species, transmission and long-distance spread, including by air travel. Although specific new infectious diseases cannot be predicted, understanding of the conditions favouring disease emergence and spread is improving. Influences include increased population density, increasingly vulnerable population age distributions and persistent poverty (Farmer, 1999). Many environmental, political and social factors contribute. These include increasing encroachment upon exotic ecosystems and disturbance of various internal biotic controls among natural ecosystems (Patzet al., 2004). There are amplified opportunities for viral mixing, such as in ‘wet animal markets’. Industrialized livestock farming also facilitates infections (such as avian influenza) emerging and spreading, and perhaps to increase in virulence. Both under- and over-nutrition and impaired immunity (including in people with poorly controlled diabetes—an obesity-associated disease now increasing globally) contribute to the persistence and spread of infectious diseases. Large-scale human-induced environmental change, including climate change, is of increasing importance.

These causes of infectious disease emergence and spread are compounded by gender, economic and structural inequities, by political ignorance and denial (particularly obvious with HIV/AIDS in parts of sub-Saharan Africa). Iatrogenesis (as with HIV in China and partial tuberculosis treatment in many developing countries), vaccine obstacles and the ‘10/90 gap’ (whereby a minority of health resources are directed towards the most severe health problems) add to this unstable picture.

We inhabit a microbially dominated world. We should therefore frame our relations with microbes primarily in ecological (not military) terms. The world’s infectious agents, perhaps with the exceptions of smallpox and polio, will not be eliminated. But much can be done to reduce human population vulnerability and avert conditions conducive to the occurrence of many infectious diseases. This is an important focus for health promotion.

DECLINING REGIONAL LIFE EXPECTANCY

The upward trajectory in life expectancy forecast in the 1980s has recently been reversed in several regions, especially in Russia and sub-Saharan Africa (McMichael et al., 2004b). These could, in principle, be either temporary aberrations or unconnected to one another. However, identifiable factors appear to link these declines.

The fall in life expectancy since 1990 in Russia is unprecedented for a technologically developed country. Many proximal causes have been documented, including alcoholism, suicide, violence, accidents and cardiovascular disease. Multiple drug-resistant tuberculosis is widespread in Russian prisons. Collectively, these factors reflect social disintegration and crisis (Shkolnikovet al., 2004).

In sub-Saharan Africa, HIV/AIDS has combined with poverty, malaria, tuberculosis, depleted soils and undernutrition (Sanchez and Swaminathan, 2005), deteriorating infrastructure, gender inequality, sexual exploitation and political taboos to foster epidemics that have reduced life expectancy, in some cases drastically. Adverse health and loss of human capital, caused by disease and the out-migration of skilled adults, have helped to ‘lock-in’ poverty. More broadly, indebtedness and ill-judged economic development policies, including charges for schooling and health services, have also impaired population health in Africa, following decades of earlier improvement. The intersectoral implications for health promotion are clear.

Conflict, most notoriously in Rwanda (André and Platteau, 1998), has also occurred on a sufficient scale to temporarily reduce life expectancy for some populations in sub-Saharan Africa. Age pyramids skewed to young adults have almost certainly played a role in this violence (Mesquida and Wiener, 1996), together with resource scarcity, pre-existing ethnic tensions, poor governance and international inactivity when crises develop.

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

Sustainable population health depends on the viability of the planet’s life-support systems (McMichael et al., 2003a). For humans, achieving and maintaining good population health is the true goal of sustainability, dependent, in turn, on achieving sustainable supportive social, economic and environmental conditions. Today, however, human-induced global environmental changes pose risks to health on unprecedented spatial and temporal scales. These environmental changes, evident at worldwide scale, include climate change, biodiversity loss, downturns in productivity of land and oceans, freshwater depletion and disruption of major elemental cycles (e.g. environmental nitrification) (McMichael, 2002). In coming decades, these long-term change processes will exact an increasing health toll via physical hazards, infectious diseases, food and water shortages, conflict and an inter-linked decline in societal capacity.

We currently extract ‘goods and services’ from the world’s natural environment about 25% faster than they can be replenished (Wackernagelet al., 2002). Our waste products are also spilling over (e.g. carbon dioxide in the atmosphere). Hence, there is now little unused global ‘biocapacity’. We are thus bequeathing an increasingly depleted and disrupted natural world to future generations. Although the resultant adverse health effects are likely to impinge unequally and, often, after time lag, this decline could eventually harm, albeit at varying levels, the entire human population.

Global climate change now attracts particular attention. Fossil fuel combustion, in particular, has caused unprecedented concentrations of atmospheric greenhouse gases. The majority expert view is that human-induced climate change is now underway (Oreskes, 2004). The power of storms, long predicted by climate change modellers to increase (Emanuel, 2005), appears (in combination with reduced wetlands and failure to maintain infrastructure) to have contributed to the 2005 New Orleans flood. WHO has estimated that, globally, over 150 000 deaths annually result from recent change in the world’s climate relative to the baseline average climate of 1961–1990 (McMichael et al., 2004a). This number will increase for at least the next several decades.

The most direct risks to future health from climate change are posed by heatwaves, exemplified by the estimated 25 000 extra deaths in Europe in August 2003, storms and floods. Climate-sensitive biotic systems will also be affected. This includes: (i) the vector–pathogen–host relationships involved in transmission of various infections, vector-borne and other, (ii) the production of aeroallergens and (iii) the agro-ecosystems that generate food. Recent changes in infectious disease occurrence in some locations—tickborne encephalitis in Sweden (Lindgren and Gustafson, 2001), cholera outbreaks in Bangladesh (Rodóet al., 2002) and, possibly, malaria in the east African highlands (Patzet al., 2002)—may partly reflect regional climatic changes.

Changes in the world’s climate and ecosystems, biodiversity losses and other large-scale environmental stresses will, in combination, affect the productivity of local agro-ecosystems, freshwater quality and supplies and the habitability, safety and productivity of coastal zones. Such impacts will cause economic dislocation and population displacement. Conflicts and migrant flows are likely to increase, potentiating violence, injury, infectious diseases, malnutrition, mental disorders and other health problems.

These and other categories of global environmental changes, often acting in combination, pose serious health risks to current and future human societies (Figure 1). The important message here is that, increasingly, human health is influenced by socio-economic and environmental changes that originate well beyond national or local boundaries. The major, perhaps irreversible, changes to the biosphere’s life-support system, including its climate system, increase the likelihood of adverse inter-generational health impacts.

Fig. 1:

Major pathways by which global and other large-scale environmental changes affect population health (based on McMichael et al., 2003b, p. 8).

EMERGING HEALTH ISSUES AND THE MDGs

In 2000, UN member states agreed on eight MDGs, with targets to be achieved by 2015. Four MDGs refer explicitly to health outcomes: eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, reducing child mortality, improving maternal health and combating HIV/AIDS, malaria and other infectious diseases. Figure 2 shows how the MDG topic areas relate to the emerging health issues discussed here.

Fig. 2:

Relationships between: (i) social and environmental conditions and their underlying economic and demographic influences and (ii) the MDG topics. (Two of this paper’s main issues, environmental changes and infectious diseases, are explicitly represented as boxes.)

Many of the MDG targets are already in jeopardy. Although all are inter-linked, the ‘environmental sustainability’ MDG has fundamental long-term importance. Without it, the other concomitants of sustainability—economic productivity, social stability and, most importantly, population health—are unachievable. An additional reason to advance the MDGs is because that will slow population growth rates and thus reduce our collective ecological footprint (Wackernagelet al., 2002).

THE FALTERING DEMOGRAPHIC AND EPIDEMIOLOGICAL TRANSITIONS

Both the demographic and epidemiological transitions are less orderly than predicted. In some regions, declining fertility rates have overshot the rate needed for an economically and socially optimal age structure. In other countries, population growth has declined substantially because of the reduced life expectancy discussed earlier (McMichael et al., 2004b). Relatedly, the future health dividend from recent reductions in poverty may be lower than that once hoped because of the emergence of the non-communicable ‘diseases of affluence’, including those due to obesity, dietary imbalances, tobacco use and air pollution.

In the 1960s, there was widespread concern over imminent famine, affecting much of the developing world. This problem was largely averted by the ‘Green Revolution’ during the 1970s and 1980s. Meanwhile, the earlier view that unconstrained population growth had little adverse impact upon environmental amenity and other conditions needed for human wellbeing gained strength. However, in the last few years, this position has been re-evaluated (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division, 2005). There is an increasing recognition of the adverse effects of rapid population growth, especially in developing countries, including from high unemployment when population increase outstrips opportunity.

Some argue that unsustainable regional population growth is characterized by age pyramids excessively skewed to young age, high levels of under- and unemployment and intense competition for limited resources. These circumstances jeopardize public health. Where there is also significant inequality and/or ethnic tension, catastrophic violence can result (André and Platteau, 1998; Butler, 2004).

Although Russia and parts of sub-Saharan Africa have vastly different demographic characteristics, there are important similarities in their recent declines in life expectancy. Both regions have a significant scarcity of public goods for health (Smith et al., 2003). In Russia, there is a lack of equality, safety and public health services. In many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, there is inadequate governance and food security as well as public safety and public health services. Viewed on an even larger scale, the miserable conditions for millions of people in these regions accord with a global class system, in which privileged groups in both developed and developing countries act (often in concert) to protect their own position at the expense of others (Butler, 2000: Navarro, 2004).

The growth of the global population and its environmental impact means that we may now be less than a generation from exhausting the biosphere’s environmental buffer, unless we can rein in our excessive demands on the natural world. If not, then the demographic and epidemiological transitions, already faltering, will be further affected. Population growth may then slow not only because of the usual development-associated fertility decrease but also because of persistently high death rates elsewhere.

Meanwhile, the growing awareness of these issues, the publicity of the MDGs, the ongoing campaigns against poverty and Third-World debt, calls for public health to address political violence and the renewed vigour of social movements for health (McCoy et al., 2004) affords new potential resources and collaborations to the global health promotion effort. These should be welcomed and acted upon.

GLOBALIZATION, TRADE, ECONOMIC POLICY AND FALTERING GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH: TOWARDS A UNIFYING EXPLANATION

The health benefits of the complex social, cultural, trade and economic phenomena that comprise ‘globalization’ are vigorously debated. Although differing viewpoints (Bettcher and Lee, 2002) are inevitable, the strength of this debate signifies that the net gain for population health from globalization is uncertain.

Several important health dividends often attributed to globalization have plausible alternative explanations. Many health gains in developing countries may be the time-lagged result of development policies and technologies introduced before the era of structural adjustment and partial economic liberalization, which heralded modern globalization. The accelerated demographic transition in China is a greatly under-recognized role in that country’s rapidly growing wealth, as were China’s earlier investments in health and education.

Proponents of gobalization assert that free trade, via ‘comparative advantage’, will benefit all populations. In reality, wealthy populations have long tilted the economic and political playing field in ways that ensure a disproportionate flow of trade benefits towards privileged populations (Mehmet, 1995). A powerful real-politic impediment to the complete removal of trade-distorting national subsidies is that this would probably entail a relatively greater loss for wealthy populations than for the poor. In contrast, the economic disadvantages incurred to date through partial market deregulation have largely been confined to relatively poor and politically weak populations in developed countries.

The pre-eminence of modern economic theory presents a major obstacle for health promoters. The narrow focus of the World Trade Organization, which largely discounts the often adverse social, environmental and public health impacts of trade, underscores the problem. Dominant economic theory evolved when environmental limits were considered remote (Daly, 1996). These theories assume that increased per capita income will offset the non-costed losses, whether these affect social welfare, environmental resources or public health. Critiques of these theories note that the harshest costs of modern economic practices fall upon ecosystems and populations with little current economic power or value, including generations not yet born.

Mobility of capital brings development, but capricious capital flight can create great hardship, including for public health. Deregulated labour conditions facilitate cheap goods, but they concentrate occupational health hazards among powerless workers. Increased labour mobility and steep economic gradients weaken family and community structures, contribute to ‘brain drain’ and promote inter-ethnic tensions. Many indices of inequality, including in health, income and environmental risk, have risen in recent decades (Butler, 2000; Parry et al., 2004).

Most critical commentary of globalization (George, 1999) is conceptual, emphasizing the adverse experiences of the disadvantaged and unborn. In contrast, the experiential feedback of the main beneficiaries of modern economic policy is largely positive. A major challenge for the promoters of health (and other forms) of justice is to adduce stronger evidence to convince policy-makers (themselves largely beneficiaries of globalization) to promote public goods, even though this may diminish the relative privilege of policy-makers and their constituencies. This is a difficult but essential task for health promotion.

EMERGING HEALTH ISSUES: THE CHALLENGES FOR HEALTH PROMOTION

In sum, global and regional inequality, narrow and outdated economic theories and an ever-nearing set of global environmental limits endanger population health. On the positive side of the ledger, there have been some gains (e.g. literacy, information sharing and food production, and new medical and public health technologies continue to confer large health benefits). Overall, though, reliance on economic, especially market-based, processes to achieve social goals and to set priorities and on technological fixes for environmental problems is poorly attuned to the long-term improvement of global human well-being and health. For that, a transformation of social institutions and norms and, hence, of public policy priorities is needed (Raskinet al., 2002). Population health can be a powerful lever in that process of social change, if health promotion can rise to this challenge.

Many of these contemporary risks to population health affect entire systems and social–cultural processes, in contrast to the continuing health risks from personal/family behaviours and localized environmental exposures. These newly recognized risks to health derive from demographic shifts, large-scale environmental changes, an economic system that emphasizes the material over other elements of well being and the cultural and behavioural changes accompanying development. Together, these emerging health risks present a huge challenge to which the wider community is not yet attuned. The risks fall outside the popular conceptual frame wherein health is viewed in relation to personal behaviours, local environmental pollutants, doctors and hospitals. In countries that promote individual choice and responsibility, there are few economic incentives for the population’s health.

Health promotion must, of course, continue to deal with the many local and immediate health problems faced by individuals, families and communities. But to do so without also seeking to guide socio-economic development and the forms and policies of regional and international governance is to risk being ‘penny wise but pound foolish’. Tackling these more systemic health issues requires multi-sectoral policy coordination (Yachet al., 2005) at community, national and international levels, via an expanded repertoire of bottom-up, top-down and ‘middle-out’ approaches to health promotion.

CONCLUSION

The essential principles of the Ottawa Charter remain valid. However, today’s health promotion challenge extends that foreseen in 1986 and requires work at many levels. There is need for proactive engagement with international agencies and programs that bear on the socio-economic fundamentals in disadvantaged regions/countries. Many low- and middle-income countries require financial aid from donor countries to achieve the health-related MDGs, to deal with emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases and to counter the emerging health risks from human-induced global environmental problems. Linkages between the health sector and civil society, including those struggling to promote development, human rights, human security and environmental protection, should be strengthened.

We need to understand that ‘sustainability’ is ultimately about optimizing human experience, especially well-being, health and survival. This requires changes in social and political organization and in how we design and manage our communities. We must live within the biosphere’s limits. Health promotion should therefore address those emerging population health influences that transcend both national boundaries and generations. The central task is to promote sustainable environmental and social conditions that confer enduring and equitable gains in population health.