SAMPLE WORK

Complete copy of FIXED INCOME INVESTMENTS ANALYSIS KASNEB STUDY TEXT is available in SOFT ( Reading using our Mobile app) and in HARD copy

Phone: 0728 776 317

Email: info@masomomsingi.com

Skip to PDF contentMASOMO MSINGI PUBLISHERS APP – Click to download and access all our REVISED soft copy materials

CHAPTER ONE

OVERVIEW OF FIXED INCOME SECURITIES

In investment management, the most important decision made is the allocation of funds among asset classes. The two major asset classes are equities and fixed income securities. Other asset classes such as real estate, private equity, hedge funds, and commodities are referred to as ‘‘alternative asset classes.’’ Our focus in this book is on one of the two major asset classes: fixed income securities.

While many people are intrigued by the exciting stories sometimes found with equities – who has not heard of someone who invested in the common stock of a small company and earned enough to retire at a young age?— we will find in our study of fixed income securities that the multitude of possible structures opens a fascinating field of study. While frequently overshadowed by the media prominence of the equity market, fixed income securities play a critical role in the portfolios of individual and institutional investors.

In its simplest form, a fixed income security is a financial obligation of an entity that promises to pay a specified sum of money at specified future dates. The entity that promises to make the payment is called the issuer of the security. Some examples of issuers are central governments such as the U.S. government and the French government, government-related agencies of a central government such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in the United States, a municipal government such as the state of New York in the United States and the city of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, a corporation such as Coca-Cola in the United States and Yorkshire Water in the United Kingdom, and supranational governments such as the World Bank.

Fixed income securities fall into two general categories: debt obligations and preferred stock. In the case of a debt obligation, the issuer is called the borrower. The investor who purchases such a fixed income security is said to be the lender or creditor. The promised payments that the issuer agrees to make at the specified dates consist of two components: interest and principal (principal represents repayment of funds borrowed) payments. Fixed income securities that are debt obligations include bonds, mortgage-backed securities, asset-backed securities, and bank loans.

In contrast to a fixed income security that represents a debt obligation, preferred stock represents an ownership interest in a corporation. Dividend payments are made to the preferred stockholder and represent a distribution of the corporation’s profit. Unlike investors who own a corporation’s common stock, investors who own the preferred stock can only realize a contractually fixed dividend payment. Moreover, the payments that must be made to preferred stockholders have priority over the payments that a corporation pays to common stockholders. In the case of the bankruptcy of a corporation, preferred stockholders are given preference over common stockholders. Consequently, preferred stock is a form of equity that has characteristics similar to bonds.

Prior to the 1980s, fixed income securities were simple investment products. Holding aside default by the issuer, the investor knew how long interest would be received and when the amount borrowed would be repaid. Moreover, most investors purchased these securities with the intent of holding them to their maturity date. Beginning in the 1980s, the fixed income world changed. First, fixed income securities became more complex. There are features in many fixed income securities that make it difficult to determine when the amount borrowed will be repaid and for how long interest will be received. For some securities it is difficult to determine the amount of interest that will be received. Second, the hold-to-maturity investor has been replaced by institutional investors who actively trades fixed income securities.

We will frequently use the terms ‘‘fixed income securities’’ and ‘‘bonds’’ interchangeably. In addition, we will use the term bonds generically at times to refer collectively to mortgage-backed securities, asset-backed securities, and bank loans.

In this chapter we will look at the various features of fixed income securities. The majority of our illustrations throughout this book use fixed income securities issued in the United States. While the U.S. fixed income market is the largest fixed income market in the world with a diversity of issuers and features, in recent years there has been significant growth in the fixed income markets of other countries as borrowers have shifted from funding via bank loans to the issuance of fixed income securities. This is a trend that is expected to continue.

I. INDENTURE AND COVENANTS

The promises of the issuer and the rights of the bondholders are set forth in great detail in a bond’s indenture. Bondholders would have great difficulty in determining from time to time whether the issuer was keeping all the promises made in the indenture. This problem is resolved for the most part by bringing in a trustee as a third party to the bond or debt contract. The indenture identifies the trustee as a representative of the interests of the bondholders.

As part of the indenture, there are affirmative covenants and negative covenants.

Affirmative covenants set forth activities that the borrower promises to do. The most common affirmative covenants are:

- To pay interest and principal on a timely basis,

- To pay all taxes and other claims when due,

- To maintain all properties used and useful in the borrower’s business in good condition and working order, and

- To submit periodic reports to a trustee stating that the borrower is in compliance with the loan agreement.

Negative covenants set forth certain limitations and restrictions on the borrower’s activities. The more common restrictive covenants are those that impose limitations on the borrower’s ability to incur additional debt unless certain tests are satisfied.

II. MATURITY

The term to maturity of a bond is the number of years the debt is outstanding or the number of years remaining prior to final principal payment. The maturity date of a bond refers to the date that the debt will cease to exist, at which time the issuer will redeem the bond by paying the outstanding balance. The maturity date of a bond is always identified when describing a bond. For example, a description of a bond might state ‘‘due 12/1/2020.’’

The practice in the bond market is to refer to the ‘‘term to maturity’’ of a bond as simply its ‘‘maturity’’ or ‘‘term.’’ As we explain below, there may be provisions in the indenture that allow either the issuer or bondholder to alter a bond’s term to maturity.

Some market participants view bonds with a maturity between 1 and 5 years as ‘‘short- term.’’ Bonds with a maturity between 5 and 12 years are viewed as ‘‘intermediate-term,’’ and ‘‘long-term’’ bonds are those with a maturity of more than 12 years.

There are bonds of every maturity. Typically, the longest maturity is 30 years. However, Walt Disney Co. issued bonds in July 1993 with a maturity date of 7/15/2093, making them 100-year bonds at the time of issuance. In December 1993, the Tennessee Valley Authority issued bonds that mature on 12/15/2043, making them 50-year bonds at the time of issuance.

SAMPLE WORK

Complete copy of FIXED INCOME INVESTMENTS ANALYSIS KASNEB STUDY TEXT is available in SOFT ( Reading using our Mobile app) and in HARD copy

Phone: 0728 776 317

Email: info@masomomsingi.com

There are three reasons why the term to maturity of a bond is important:

- Term to maturity indicates the time period over which the bondholder can expect to receive interest payments and the number of years before the principal will be paid in

- The yield offered on a bond depends on the term to The relationship between the yield on a bond and maturity is called the yield curve.

- The price of a bond will fluctuate over its life as interest rates in the market change. The price volatility of a bond is a function of its maturity (among other variables). More specifically, all other factors constant, the longer the maturity of a bond, the greater the price volatility resulting from a change in interest

III. PAR VALUE

The par value of a bond is the amount that the issuer agrees to repay the bondholder at or by the maturity date. This amount is also referred to as the principal value, face value, redemption value, and maturity value. Bonds can have any par value.

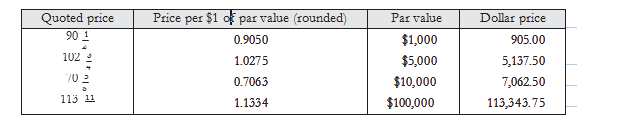

Because bonds can have a different par value, the practice is to quote the price of a bond as a percentage of its par value. A value of ‘‘100’’ means 100% of par value. So, for example, if a bond has a par value of $1,000 and the issue is selling for $900, this bond would be said to be selling at90 If a bond with a par value of $5,000 is selling for $5,500, the bond is said to be selling for 110. When computing the dollar price of a bond in the United States, the bond must first be converted into a price per US$1 of par value. Then the price per $1 of par value is multiplied by the par value to get the dollar price. Here are examples of what the dollar price of a bond is, given the price quoted for the bond in the market, and the par amount involved in the transaction:

Notice that a bond may trade below or above its par value. When a bond trades below its par value, it said to be trading at a discount. When a bond trades above its par value, it said to be trading at a premium. The reason why a bond sells above or below its par value.

IV. COUPON RATE

The coupon rate, also called the nominal rate, is the interest rate that the issuer agrees to pay each year. The annual amount of the interest payment made to bondholders during the term of the bond is called the coupon. The coupon is determined by multiplying the coupon rate by the par value of the bond. That is,

Coupon = coupon rate × par value

For example, a bond with an 8% coupon rate and a par value of $1,000 will pay annual interest of $80 ( $1, 000 0.08).

When describing a bond of an issuer, the coupon rate is indicated along with the maturity date. For example, the expression ‘‘6s of 12/1/2020’’ means a bond with a 6% coupon rate maturing on 12/1/2020. The ‘‘s’’ after the coupon rate indicates ‘‘coupon series.’’ In our example, it means the ‘‘6% coupon series.’’

In the United States, the usual practice is for the issuer to pay the coupon in two semiannual installments. Mortgage-backed securities and asset-backed securities typically pay interest monthly. For bonds issued in some markets outside the United States, coupon payments are made only once per year.

The coupon rate also affects the bond’s price sensitivity to changes in market interest rates.

All other factors constant, the higher the coupon rate, the less the price will change in response to a change in market interest rates.

A. Zero-Coupon Bonds

Not all bonds make periodic coupon payments. Bonds that are not contracted to make periodic coupon payments are called zero-coupon bonds. The holder of a zero-coupon bond realizes interest by buying the bond substantially below its par value (i.e., buying the bond at a discount). Interest is then paid at the maturity date, with the interest being the difference between the par value and the price paid for the bond. So, for example, if an investor purchases a zero-coupon bond for 70, the interest is 30. This is the difference between the par value (100) and the price paid (70).

B. Step-Up Notes

There are securities that have a coupon rate that increases over time. These securities are called step-up notes because the coupon rate ‘‘steps up’’ over time. For example, a 5-year step-up note might have a coupon rate that is 5% for the first two years and 6% for the last three years. Or, the step-up note could call for a 5% coupon rate for the first two years, 5.5% for the third and fourth years, and 6% for the fifth year. When there is only one change (or step up), as in our first example, the issue is referred to as a single step-up note. When there is more than one change, as in our second example, the issue is referred to as a multiple step-up note.