Introduction

In this chapter we cover the main elements of internal control and risk

management frameworks. You will have encountered internal controls in your

auditing studies. In this chapter we take an overview of the main frameworks

rather than looking at controls in detail.

The UK Turnbull report has provided a lot of useful guidance on internal control,

which is referred to in this and other chapters. Turnbull stresses the importance

of control systems as means of managing risks. In Section 3 we introduce the

very important COSO enterprise risk management framework. Chapters 5 to 8 of

this text discuss in detail the elements this framework identifies.

In Section 4 we cover other international control frameworks, which each

provide slightly different perspectives.

This is a very important chapter. The examiner has stressed how important a

sound system of internal control is.

Study guide

| Intellectual level | ||

| B1 | Management control systems in corporate governance | |

| (a) | Define and explain internal management control. | 2 |

| (b) | Explain and explore the importance of internal control and risk management in corporate governance. | 3 |

| (c) | Describe the objectives of internal control systems and how they can help prevent fraud and error. | 2 |

| (e) | Identify and assess the importance of elements or components of internal control systems. | 3 |

| B2 | Internal control, audit and compliance in corporate governance | |

| (e) | Explore and evaluate the effectiveness of internal control systems. | 3 |

Exam guide

You may be asked to provide an appropriate control framework for an organisation or assess a framework that is described in a scenario. Look out in particular for whether the underlying control environment appears to be sound.

1 Purposes of internal control systems

FAST FORWARD

Internal controls should help organisations counter risks, maintain the quality of financial reporting and comply with laws and regulations. They provide reasonable assurance that organisations will fulfil their strategic objectives.

Key term An internal control is any action taken by management to enhance the likelihood that established

objectives and goals will be achieved. Control is the result of proper planning, organising and directing by

management. (Institute of Internal Auditors)

1.1 Internal management control 12/14

Internal management control can be viewed as management planning, organising and directing performance so that organisational objectives are achieved. Planning and organising includes establishing objectives, determining and obtaining the resources required to fulfil objectives and defining the policies and procedures that will be used in the organisation’s operations. Directing means ensuring resources are used efficiently and effectively, and also ensuring that operational tasks are carried out in line with the established procedures and policies.

1.1.1 The process of control

The cybernetic control model describes the process of control. A general cybernetic control model has six key stages:

| Identification of objectives | Objectives for the process being controlled must exist, for without an aim or purpose control has no meaning. Objectives are set in response to environmental pressures such as customer demand. |

| Setting targets | A target or prediction of the process being controlled is required so that managers can see whether or not objectives have been achieved and whether action will be needed to remedy problems. Targets could include budgets or cost standards. |

| Measuring achievements/outputs |

The output of the process must be measurable. |

| Comparing achievements with targets | Managers need to compare the actual outcomes of the process with the plan – this is known as obtaining feedback. |

| Identifying corrective action | It must be possible to take action so that failures to meet objectives can be reduced or eliminated. |

| Implementing corrective action | Action could involve changing objectives, resource inputs, the process or the whole system |

1.1.2 Important features of control systems

Fisher has suggested that management control systems can be viewed in terms of the following criteria.

- Flexibility and ease of achievement of targets

- Relative importance of numerical and subjective performance measures

- Relative importance of short- and long-term measures

- Consistency of measures used across the organisation

- Whether management actively intervenes or intervenes by exception

- How automatic control mechanisms are

- Extent of participation below top management Extent of reliance on social relationships

1.2 Effectiveness of control systems 12/07

In order for internal controls to function properly, they have to be well directed. Managers and staff will be more able (and willing) to implement controls successfully if it can be demonstrated to them what the objectives of the control systems are. Objectives also provide a yardstick for the board when they come to monitor and assess how controls have been operating.

1.3 Purposes of control systems 12/07

The UK Turnbull report provides a helpful summary of the main purposes of an internal control system.

Turnbull comments that internal control consists of ‘the policies, processes, tasks, behaviours and other aspects of a company that taken together:

- Facilitate its effective and efficient operation by enabling it to respond appropriately to significant business, operational, financial, compliance and other risks to achieving the company’s objectives. This includes the safeguarding of assets from inappropriate use or from loss and fraud and ensuring that liabilities are identified and managed.

- Help ensure the quality of internal and external reporting. This requires the maintenance of proper records and processes that generate a flow of timely, relevant and reliable information from within and outside the organisation.

- Help ensure compliance with applicable laws and regulations, and also with internal policies with respect to the conduct of businesses.’

1.3.1 Characteristics of internal control systems

The Turnbull report summarises the key characteristics of the internal control systems. They should:

- Be embedded in the operations of the company and form part of its culture

- Be capable of responding quickly to evolving risks within the business

- Include procedures for reporting immediately to management significant control failings and weaknesses together with control action being taken

We shall talk more about each of these later in this text.

The Turnbull report goes on to say that a sound system of internal control reduces but does not eliminate the possibilities of losses arising from poorly judged decisions, human error, deliberate circumvention of controls, management override of controls and unforeseeable circumstances. Systems will provide reasonable (not absolute) assurance that the company will not be hindered in achieving its business objectives and in the orderly and legitimate conduct of its business, but won’t provide certain protection against all possible problems.

1.4 Risk

The Turnbull guidance and other guidance on control systems places great emphasis on how control systems deal with risk. In the next few chapters therefore much of our discussion will focus on risk.

| Risk is a condition in which there exists a quantifiable dispersion in the possible results of any activity.

Hazard is the impact if the risk materialises. Uncertainty means that you do not know the possible outcomes and the chances of each outcome occurring. |

Key terms

In other words, risk is the probability, hazard is the consequences, of results deviating from expectations. However, risk is often used as a generic term to cover hazard as well.

|

|||||||||

Make your own list, specific to the organisations that you are familiar with. Here is a list extracted from an article by Tom Jones, ‘Risk Management’ (Administrator, April 1993). It is illustrative of the range of risks faced and is not exhaustive.

- Fire, flood, storm, impact, explosion, subsidence and other disasters

- Accidents and the use of faulty products

- Error: loss through damage or malfunction caused by mistaken operation of equipment or wrong operation of an industrial programme

- Theft and fraud

- Breaking social or environmental regulations

- Political risks (the appropriation of foreign assets by local governments or of barriers to the repatriation of overseas profit)

- Computers: fraud, viruses and espionage

- Product tamper

- Malicious damage

1.4.1 Types of risk

There are various types of risk that exist in business and in life generally.

Key terms Fundamental risks are those that affect society in general, or broad groups of people, and are beyond the

control of any one individual. For example, there is the risk of atmospheric pollution which can affect the health of a whole community but which may be quite beyond the power of an individual within it to control.

Particular risks are risks over which an individual may have some measure of control. For example, there is a risk attached to smoking and we can mitigate that risk by refraining from smoking.

Speculative risks are those from which either good or harm may result. A business venture, for example, presents a speculative risk because either a profit or loss can result.

Pure risks are those whose only possible outcome is harmful. The risk of loss of data in computer systems caused by fire is a pure risk because no gain can result from it.

Exam focus It is important to emphasise that not all risks are pure risks. Plenty of risks have favourable as well as point adverse consequences. As we shall see, businesses will take positive as well as negative impacts into account when deciding how risks should be managed.

1.5 Risk and business

A key point to emphasise is that risk is bound up with doing business. The basic principle is that ‘you have to speculate to accumulate’.

It may not be possible to eliminate risks without undermining the whole basis on which the business operates, or without incurring excessive costs and insurance premiums. Therefore in many situations there is likely to be a level of residual risk which it is simply not worth eliminating.

There are some benefits to be derived from the management of risk, possibly at the expense of profits, such as:

- Predictability of cash flows

- Limitation of the impact of potentially bankrupting events

- Increased confidence of shareholders and other investors

However, boards should not just focus on managing negative risks but should also seek to limit uncertainty and to manage speculative risks and opportunities in order to maximise positive outcomes and hence shareholder value.

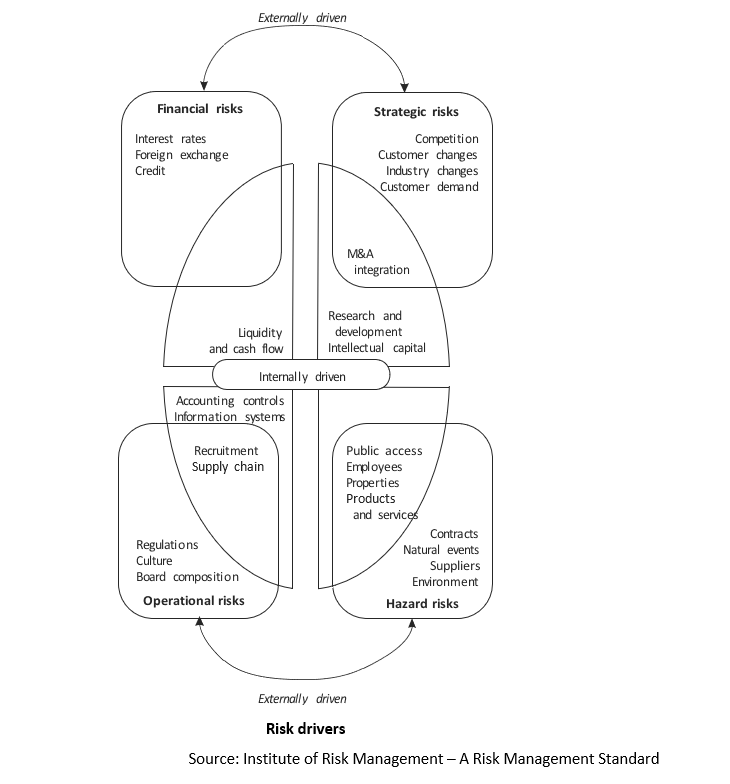

In its Risk Management Standard, the Institute of Risk Management linked key value drivers for a business with major risk categories.

During 2007 a number of UK Government departments suffered security breaches relating to the sensitive personal data they stored. Some criticisms were made of the security of the computer systems; for example, the failure to encrypt information properly.

However, the most serious breaches related to simple errors, which elaborate computer applications could not prevent. The most notorious error related to the loss of personal data of every child benefit claimant (around 25 million). The material was sent between government departments on two disks, using the ordinary postal system, but was delayed en route.

1.6 Risk and corporate governance

One obvious link between risk and corporate governance is the issue of shareholders’ concerns, here about the relationship between the level of risks and the returns achieved, being addressed.

A further issue is the link (or lack of) between directors’ remuneration and risks taken. If remuneration does not link directly with risk levels, but does link with turnover and profits achieved, directors could decide that the company should bear risk levels that are higher than shareholders deem desirable. It has therefore been necessary to find other ways of ensuring that directors pay sufficient attention to risk management and do not take excessive risks. Corporate governance guidelines therefore require directors to:

- Establish appropriate control mechanisms for dealing with the risks the organisation faces

- Monitor risks themselves by regular review and a wider annual review

- Disclose their risk management processes in the accounts

Exam focus Particularly important areas include safeguarding of shareholders’ investment and company assets, point facilitation of operational effectiveness and efficiency, and contribution to the reliability of reporting.

| 2 Internal control frameworks | 12/08, 12/14 |

FAST FORWARD

The internal control framework includes the control environment and control procedures. Other important elements are the risk assessment and response processes, the sharing of information and monitoring the environment and operation of the control system.

2.1 Need for control framework

Organisations need to consider the overall framework of controls, since controls are unlikely to be very effective if they are developed sporadically around the organisation and their effectiveness will be very difficult to measure by internal audit and ultimately by senior management.

2.2 Control environment and control procedures

Key terms The internal control framework comprises the control environment and control procedures. It includes

all the policies and procedures (internal controls) adopted by the directors and management of an entity to assist in achieving their objective of ensuring, as far as practicable, the orderly and efficient conduct of its business, including:

- Adherence to internal policies

- The safeguarding of assets

- The prevention and detection of fraud and error

- The accuracy and completeness of the accounting records

- The timely preparation of reliable financial information

Internal controls may be incorporated within computerised accounting systems. However, the internal control system extends beyond those matters which relate directly to the accounting system.

Perhaps the simplest framework for internal control draws a distinction between:

- Control or internal environment – the overall context of control, in particular the culture, infrastructure and architecture of control and attitude of directors and managers towards control (discussed in Chapter 5)

- Control procedures – the detailed controls in place (discussed in Chapter 7) The Turnbull report also highlights the importance of:

- Information and communication processes (covered in Chapter 8)

- Processes for monitoring the continuing effectiveness of the system of internal control (covered in Chapter 8)

2.3 Purposes of internal control framework

- Achieving orderly conduct of business

Internal controls should ensure the organisation’s operations are conducted effectively and efficiently. In particular they should enable the organisation to respond appropriately to business, operational, financial, compliance and other risks to achieving its objectives.

- Adherence to internal policies and laws

Controls should ensure that the organisation and its staff comply with applicable laws and regulations, and that staff comply with internal policies with respect to the conduct of the business.

- Safeguarding assets

Controls should ensure that assets are optimally utilised and stop assets being used inappropriately. They should prevent the organisation losing assets through theft or poor maintenance.

- Prevention and detection of fraud

Controls should include measures designed to prevent fraud, such as segregation of duties and checking references when staff are recruited. The information that systems provide should highlight unusual transactions or trends that may be signs of fraud.

- Accuracy and completeness of accounting records

Controls should ensure that records and processes are kept that generate a flow of timely, relevant and reliable information that aids management decision-making.

- Timely preparation of reliable financial information

They should ensure that published accounts give a true and fair view, and other published information is reliable and meets the requirements of those stakeholders to whom it is addressed.

Exam focus There may be some marks available for a general description of key features of a business’s control point systems, or its objectives (tested in December 2008).

2.4 Internal control frameworks and risk

Turnbull states that in order to determine its policies in relation to internal control and decide what constitutes a sound system of internal control, the board should consider:

- The nature and extent of risks facing the company

- The extent and categories of risk which it regards as acceptable for the company to bear

- The likelihood of the risks concerned materialising

- The company’s ability to reduce the incidence and impact on the business of risks that do materialise The costs of operating particular controls relative to the benefits obtained in managing the related risks

Exam focus December 2008 Question 3 asked for a description of the objectives of internal control. point

Turnbull goes on to stress that an organisation’s risks are continually changing, as its objectives, internal organisation and business environment are continually evolving. New markets and new products bring further risks and also change overall organisation risks. Diversification may reduce risk (the business is not overdependent on a few products) or may increase it (the business is competing in markets in which it is ill equipped to succeed). Therefore the organisation needs to constantly re-evaluate the nature and extent of risks to which it is exposed.

COSO points out that an organisation needs to establish clear and coherent objectives in order to be able to tackle risks effectively. The risks that are important are those that are linked with achievement of the organisation’s objectives. In addition, there should be control mechanisms that identify and adjust for the risks that arise out of changes in economic, industry, regulatory and operating conditions.

2.5 Challenges in developing internal control 6/08, 6/09, 12/11, 12/13

Guidance from the Committee of Sponsoring Organisations of the Treadway Commission (COSO – discussed below) has highlighted a number of potential problems that smaller companies may face when developing internal control. These include:

- Insufficient staff resources to maintain segregation of duties

- Domination of activities by management, with significant opportunities for management override of controls. This arises from smaller companies having fewer levels of management with wider spans of control and their managers having significant ownership interests or rights

- Inability to recruit directors with the requisite financial reporting or other expertise

- Inability to recruit and retain staff with sufficient knowledge of, and experience in, financial reporting

- Management having a wide range of responsibilities and thus having insufficient time to focus on accounting and financial reporting

- Control over computer information systems with limited in-house technical expertise

2.6 Limitations of internal controls 6/08, 6/09, 12/11, 12/12

In addition, an internal control framework in any organisation can only provide the directors with reasonable assurance that their objectives are reached, because of inherent limitations, including:

- The costs of control not outweighing their benefits; sometimes setting up an elaborate system of controls will be too costly when compared with the financial losses those controls may prevent Poor judgement in decision-making

- The potential for human error or fraud

- Collusion between employees

- The possibility of controls being bypassed or overridden by management or employees

- Controls being designed to cope with routine and not non-routine transactions

- Controls being unable to cope with unforeseen circumstances

- Controls depending on the method of data processing – they should be independent of the method of data processing

- Controls not being updated over time

A large college has several sites and employs hundreds of teaching staff. The college has recently discovered a serious fraud involving false billings for part-time teaching.

The fraud involved two members of staff. M is a clerk in the payroll office who is responsible for processing payments to part-time teaching staff. P is the head of the Business Studies department at the N campus. Part-time lecturers are required to complete a monthly claim form which lists the classes taught and the total hours claimed. These forms must be signed by their head of department, who sends all signed forms to M. M checks that the class codes on the claim forms are valid, that hours have been budgeted for those classes and inputs the information into the college’s payroll package.

The college has a separate personnel department that is responsible for maintaining all personnel files. Additions to the payroll must be made by a supervisor in the personnel office. The payroll package is programmed to reject any claims for payment to employees whose personnel files are not present in the system.

M had gained access to the personnel department supervisor’s office by asking the college security officer for the loan of a pass key because he had forgotten the key to his own office. M knew that the office would be unoccupied that day because the supervisor was attending a wedding. M logged onto the supervisor’s computer terminal by guessing her password, which turned out to be the registration number of the supervisor’s car. M then added a fictitious part-time employee, who was allocated to the N campus Business Studies department.

P then began making claims on behalf of the fictitious staff member and submitting them to M. M signed off the forms and input them as normal. The claims resulted in a steady series of payments to a bank account that had been opened by P. The proceeds of the fraud were shared equally between M and P.

The fraud was only discovered when the college wrote to every member of staff with a formal invitation to the college’s centenary celebration. The letter addressed to the fictitious lecturer was returned as undeliverable and the personnel department became suspicious when they tried to contact this person in order to update his contact details. By then M and P had been claiming for non-existent teaching for three years without detection by external or internal audit.

Required

Evaluate the difficulties in implementing controls that would have prevented and detected this fraud.

Small amounts

The college employs hundreds of teaching staff on full- and part-time contracts. Payments for one fictitious employee would not be large enough to attract the attention of internal auditors automatically. Even if auditors had checked a random sample of payments each year, given the large population the probability was that the fictitious employee would not be discovered for some time, as indeed happened.

Falsification of records

The records of the employee appeared to be genuine and a routine payment to a lecturer, entered on the payroll supervisor’s log-in and signed off by P. There was nothing unusual about these payments that anyone reviewing them could have identified.

Use of payroll supervisor’s log-on

The payroll supervisor would normally have been the third person involved with this transaction because of their involvement at the initial stage. However, P was able to bypass the need for the supervisor’s involvement by taking advantage of her absence and correctly guessing how to enter the computer on the supervisor’s password.

Collusion

Once the fictitious lecturer’s details had been entered, the college’s systems meant that two people had to be involved for each payment to a lecturer to be made, the head of department and the payroll clerk. The involvement of both in the fraud meant that the segregation of duties between the two staff, that P authorised the payment and M entered it, was lost.

Involvement of senior staff

The system also depended on the authorisation of payments by P. The system would have produced for P a record of the lecturers who had been paid for working in P’s department. However, review of this by P would have been worthless, as he would not have reported the fictitious lecturer. The system effectively relied on P’s honesty. Many systems are designed on the basis that senior staff act honestly. As P had been appointed to a senior position, there presumably was no indication in his previous record that suggested he could not be trusted.

| Question 1 in June 2008 asked about the problems of applying internal controls to subcontractors. |

Exam focus point

3 COSO’s framework

FAST FORWARD

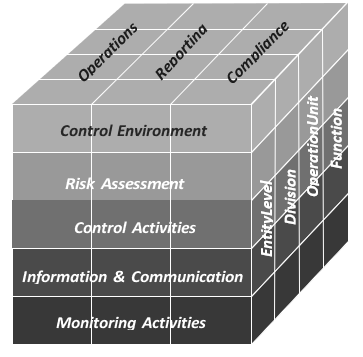

COSO’s enterprise risk management framework provides a coherent framework for organisations to deal with risk, based on the following components.

- Control environment

- Risk assessment

- Control activities

- Information and communications

- Monitoring activities

COCO is an alternative framework that emphasises the importance of the commitment of those operating the system.

3.1 Nature of enterprise risk management 6/14

We have seen that internal control systems should be designed to manage risks effectively. There are various frameworks for risk management, but we shall be looking in particular at the framework established by the Committee of Sponsoring Organisations of the Treadway Commission (COSO).

COSO published guidance on internal control, Internal Control – Integrated Framework, in 1992. It published wider guidance on Enterprise Risk Management in 2004. In 2006 COSO issued Internal Control over Financial Reporting – Guidance for Smaller Companies. This guidance was designed to supplement the guidance in Internal Control – Integrated Framework, in the light of the requirement in s 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley legislation for management of public companies to assess and report on the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting. An updated version of the framework was issued in 2013 to reflect the increasingly global nature of business activity, the impact of technological advances, the increasing complexity of rules and regulations, and stakeholder concerns over risk management and the prevention of fraud.

Key terms Enterprise risk management is a process, effected by an entity’s board of directors, management and

other personnel, applied in strategy setting and across the enterprise, designed to identify potential events that may affect the entity and manage risks to be within its risk appetite, to provide reasonable assurance regarding the achievement of entity objectives.

Internal control is a process effected by an entity’s board of directors, management and other personnel designed to provide reasonable assurance regarding the achievement of objectives in the following categories.

- Effectiveness and efficiency of operations

- Reliability of reporting

- Compliance with laws and regulations COSO

COSO states that enterprise risk management has the following characteristics.

- It is a process, a means to an end, which should ideally be intertwined with existing operations and exist for fundamental business reasons.

- It is operated by people at every level of the organisation and is not just paperwork. It provides a mechanism for helping people to understand risk, their responsibilities and levels of authority.

- It is applied in strategy setting, with management considering the risks in alternative strategies.

- It is applied across the enterprise. This means it takes into account activities at all levels of the organisation, from enterprise-level activities such as strategic planning and resource allocation, to business unit activities and business processes. It includes taking an entity-level portfolio view of risk. Each unit manager assesses the risk for their unit. Senior management ultimately consider these unit risks and also interrelated risks. Ultimately they will assess whether the overall risk portfolio is consistent with the organisation’s risk appetite.

- It is designed to identify events potentially affecting the entity and manage risk within its risk appetite, the amount of risk it is prepared to accept in pursuit of value. The risk appetite should be aligned with the desired return from a strategy.

- It provides reasonable assurance to an entity’s management and board. Assurance can at best be reasonable since risk relates to the uncertain future.

- It is geared to the achievement of objectives in a number of categories, including supporting the organisation’s mission, making effective and efficient use of the organisation’s resources, ensuring reporting is reliable, and complying with applicable laws and regulations.

Because these characteristics are broadly defined, they can be applied across different types of organisations, industries and sectors. Whatever the organisation, the framework focuses on achievement of objectives.

An approach based on objectives contrasts with a procedural approach based on rules, codes or procedures. A procedural approach aims to eliminate or control risk by requiring conformity with the rules. However, a procedural approach cannot eliminate the possibility of risks arising because of poor management decisions, human error, fraud or unforeseen circumstances arising.

3.2 Framework of enterprise risk management

The COSO framework consists of five interrelated components.

| Component | Explanation |

| Control environment (Chapter 5) | This covers the tone of an organisation, and sets the basis for how risk is viewed and addressed by an organisation’s people, including risk management philosophy and risk appetite, integrity and ethical values, and the environment in which they operate. The board’s attitude, participation and operating style will be a key factor in determining the strength of the control environment. An unbalanced board, lacking appropriate technical knowledge and experience, diversity and strong, independent voices is unlikely to set the right tone. The example set by board members may be undermined by a failure of management in divisions or business units. Mechanisms to control line management may not be sufficient or may not be operated properly. Line managers may not be aware of their responsibilities or may fail to exercise them properly. |

| Risk assessment

(Chapters 6 and 7) |

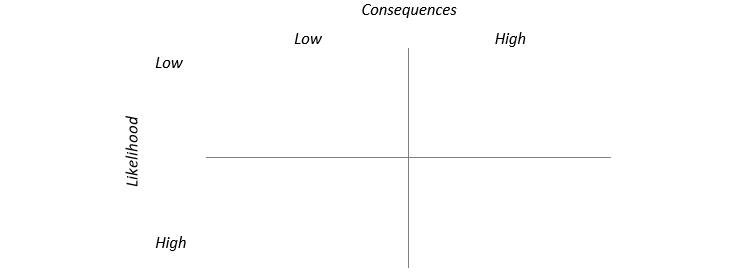

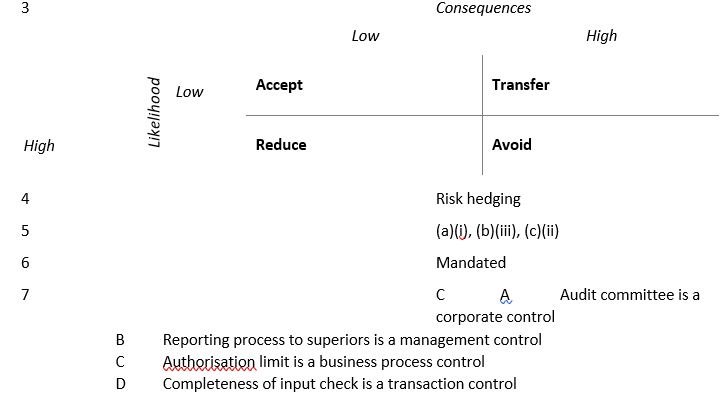

Risks are analysed considering likelihood and impact as a basis for determining how they should be managed. The analysis process should clearly determine which risks are controllable, and which risks are not controllable.

The COSO guidance stresses the importance of employing a combination of qualitative and quantitative risk assessment methodologies. As well as assessing inherent risk levels, the organisation should also assess residual risks left after risk management actions have been taken. Risk assessment needs to be dynamic, with managers considering the effect of changes in the internal and external environments that may render controls ineffective. |

| Control activities

(Chapter 7) |

Policies and procedures are established and implemented to help ensure the risk responses are effectively carried out. COSO guidance suggests that a mix of controls will be appropriate, including prevention and detection and manual and automated controls. COSO also stresses the need for controls to be performed across all levels of the organisation, at different stages within business processes and over the technology environment. |

| Component | Explanation |

| Information and communication

(Chapter 8) |

Relevant information is identified, captured and communicated in a form and timeframe that enable people to carry out their responsibilities. The information provided to management needs to be relevant and of appropriate quality. It also must cover all the objectives shown on the top of the cube. Effective communication should be broad – flowing up, down and across the entity. There needs to be communication with staff. Communication of risk areas that are relevant to what staff do is an important means of strengthening the internal environment by embedding risk awareness in staff’s thinking. There should also be effective communication with third parties such as shareholders and regulators. |

| Monitoring activities (Chapter 8) | Risk control processes are monitored and modifications are made if necessary. Effective monitoring requires active participation by the board and senior management, and strong information systems, so the data senior managers need is fed to them. COSO has drawn a distinction between regular review (ongoing monitoring) and periodic review (separate evaluation). However weaknesses are identified, the guidance stresses the importance of feedback and action. Weaknesses should be reported, assessed and their root causes corrected. |

Diagrammatically all the above may be summarised as follows.

Benefits of enterprise risk management 6/09

COSO highlights a number of advantages of adopting the process of enterprise risk management.

| Alignment of risk appetite and strategy | The framework demonstrates to managers the need to consider risk toleration. They then set objectives aligned with business strategy and develop mechanisms to manage the accompanying risks and to ensure risk management becomes part of the culture of the organisation, embedded into all its processes and activities. |

| Link growth, risk and return | Risk is part of value creation, and organisations will seek a given level of return for the level of risk tolerated. |

| Choose best risk response | Enterprise risk management helps the organisation select whether to reduce, eliminate or transfer risk. |

| Minimise surprises and losses | By identifying potential loss-inducing events, the organisation can reduce the occurrence of unexpected problems. |

| Identify and manage risks across the organisation | As indicated above, the framework means that managers can understand and aggregate connected risks. It also means that risk management is seen as everyone’s responsibility, experience and practice is shared across the business and a common set of tools and techniques is used. |

| Provide responses to multiple risks | For example risks associated with purchasing, over- and undersupply, prices and dubious supply sources might be reduced by an inventory control system that is integrated with suppliers. |

| Seize opportunities | By considering events as well as risks, managers can identify opportunities as well as losses. |

| Rationalise capital | Enterprise risk management allows management to allocate capital better and make a sounder assessment of capital needs. |

3.4 Criticisms of enterprise risk management

There have been some criticisms made of COSO’s framework:

- Internal focus

One criticism of the ERM model has been that it starts at the wrong place. It begins with the internal and not the external environment. Critics claim that it does not reflect sufficiently the impact of the competitive environment, regulation and external stakeholders on risk appetite and management and culture.

- Risk identification

The ERM has been criticised for discussing risks primarily in terms of events, particularly sudden events with major consequences. Critics claim that the guidance insufficiently emphasises slow changes that can give rise to important risks; for example, changes in internal culture or market sentiment.

- Risk assessment

The ERM model has been criticised for encouraging an oversimplified approach to risk assessment. It has been claimed that the ERM encourages an approach which thinks in terms of a single outcome of a risk materialising. This outcome could be an expected outcome or it could be a worst-case result. Many risks will have a range of possible outcomes if they materialise, for example extreme weather, and risk assessment needs to consider this range.

- Stakeholders

The guidance fails to discuss the influence of stakeholders, although many risks that organisations face are due to a conflict between the organisation’s objectives and those of its stakeholders.

3.5 Impacts of enterprise risk management

Although COSO’s guidance is non-mandatory, it has been influential because it provides frameworks against which risk management and internal control systems can be assessed and improved. Corporate scandals, arising in companies where risk management and internal control were deficient, and attempts to regulate corporate behaviour as a result of these scandals have resulted in an environment where guidance on best practice in risk management and internal control has been particularly welcome.

3.6 The COCO framework

A slightly different framework is the criteria of control or COCO framework developed by the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA).

3.6.1 Purpose

The COCO framework stresses the need for all aspects of activities to be clearly directed with a sense of purpose. This includes:

- Overall objectives, mission and strategy

- Management of risk and opportunities

- Policies

- Plans and performance measures

The corporate purpose should drive control activities and ensure controls achieve objectives.

3.6.2 Commitment

The framework stresses the importance of managers and staff making an active commitment to identify themselves with the organisation and its values, including ethical values, authority, responsibility and trust.

3.6.3 Capability

Managers and staff must be equipped with the resources and competence necessary to operate the control systems effectively. This includes not just knowledge and resources but also communication processes and co-ordination.

3.6.4 Action

If employees are sure of the purpose, are committed to do their best for the organisation and have the ability to deal with problems and opportunities then the actions they take are more likely to be successful. 3.6.5 Monitoring and learning

An essential part of commitment to the organisation is a commitment to its evolution. This includes:

- Monitoring external environments

- Monitoring performance

- Reappraising information systems

- Challenging assumptions

- Reassessing the effectiveness of internal controls

Above all each activity should be seen as part of a learning process that lifts the organisation to a higher dimension.

| This emphasises the importance of feedback and continuous improvement in control systems and is something worth looking for in exam scenarios – whether the organisation appears capable of making essential improvements. |

Exam focus point

4 Evaluating control systems

| A number of factors should be considered when evaluating control systems. |

FAST FORWARD

4.1 Principles or rules 6/10

We discussed whether to adopt a principles- or rules-based approach to corporate governance in Chapter 2. This debate is particularly significant for internal controls.

Having rules requiring organisations to implement internal controls should mean that controls are applied consistently by organisations. External stakeholders dealing with these organisations will have the assurance that they should have certain prescribed controls in place. However, this does not mean that all organisations will be operating the same controls with the same effectiveness.

A principles-based approach to internal control implementation means that organisations can adopt controls that are most appropriate and cost effective for them, based on their size and risk profile and the sector in which they operate.

4.2 Assessment of control systems

We shall look in detail at the different elements of risk management and control systems in later chapters, but the following general points apply to review of control systems.

4.2.1 Objectives

The controls in place need to help the company fulfil key business objectives, including conducting its operations efficiently and effectively, safeguarding its assets and responding to the significant risks it faces.

4.2.2 Links with risks

Links between controls and risks faced are particularly important, with the organisation needing a clear framework for dealing effectively with risks. Key elements are the board defining risk appetite, which will determine which risks are significant. There need to be reliable systems in place for identifying and assessing the magnitude of risks.

4.2.3 Control system compatibility

Guidance on control procedures needs to be supported by other aspects of the control system, and the overall systems need to deliver a consistent message about the importance of controls. Human resource policies and the company’s performance reward systems should provide incentives for good behaviour and deal with flagrant breaches.

4.2.4 Mix of controls

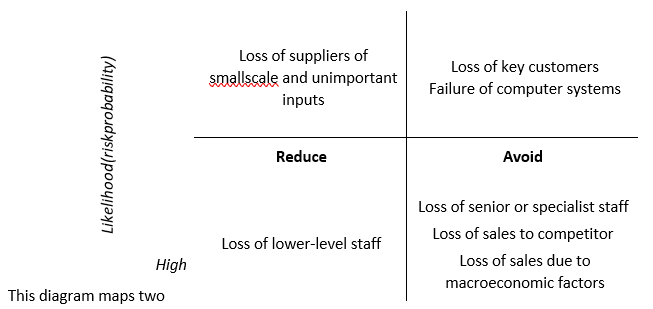

Detailed controls at the transaction level will not make all that much difference unless there are other controls further up the organisation. There should ideally be a pyramid of controls in place, ranging from corporate controls at the top of an organisation (for example ethical codes), management controls (budgets), process controls (authorisation limits) and transaction controls (completeness controls). Controls shouldn’t just cover the financial accounting areas, but should include non-financial controls as well.

4.2.5 Human resource issues

How well control procedures operate will also be determined by the authority and abilities of the individuals who operate the controls. There need to be clear job descriptions that identify how much authority and discretion individuals have at different levels of the organisation. Controls can be also be undermined if the people who operate them make mistakes. Therefore managers and staff need to have the requisite knowledge and skills to be able to operate controls effectively. Documentation and training will be required, and individuals’ abilities assessed on a continuing basis as part of the appraisal process.

4.2.6 Control environment

The control environment (discussed further in the next chapter) matters because the company’s culture will determine how seriously control procedures are taken. If there is evidence that directors are overriding controls, this will undermine them. If staff resent controls, they may be tempted to collude to render controls ineffective.

4.2.7 Review of controls

Directors should demonstrate their commitment to control by reviewing internal controls.

4.2.8 Information sources

In order to carry out effective reviews of controls, the board needs to ensure it is receiving sufficient information. There should be a system in place of regular reporting by subordinates and control functions as well as reports on high-risk activities. The board also needs to receive confirmation that weaknesses identified in previous reviews have been resolved. Finally there needs to be clear systems of reporting problems to the board.

4.2.9 Feedback and response

A basic principle of control system design is that the feedback received should be used as the basis for taking action to change the controls or modify the overall control systems. There should be rapid responses if serious problems are picked up, for example involvement of senior management in reviewing possible fraud.

4.2.10 Costs and benefits

Rational consideration of whether the costs of operating controls are worth the benefits of preventing and detecting problems should be an integral part of the board’s review process. Directors may decide not to operate certain controls on the grounds that they are prepared to accept the risks of not doing so.

|

|||||||||

The following strike us as significant. You may well have come up with other points.

- Risk management is a circular, continuous process, feeding on itself with the aim of ensuring continuous improvement.

- The different faces of the COSO model emphasise the need for setting objectives at different levels, and for risk management to be effective in each business unit, division, etc.

- COCO emphasises the need for staff to have the right attitudes, commitment and experience.

- The approaches stress the need for monitoring by the board.

Chapter Roundup

| | Internal controls should help organisations counter risks, maintain the quality of financial reporting and comply with laws and regulations. They provide reasonable assurance that organisations will fulfil their strategic objectives. |

| | The internal control framework includes the control environment and control procedures. Other important elements are the risk assessment and response processes, the sharing of information and monitoring the environment and operation of the control system. |

|

|

COSO’s enterprise risk management framework provides a coherent framework for organisations to deal with risk, based on the following components.

– Control environment – Risk assessment – Control activities – Information and communications – Monitoring activities COCO is an alternative framework that emphasises the importance of the commitment of those operating the system. |

| | A number of factors should be considered when evaluating control systems. |

Quick Quiz

- What according to Turnbull should a good system of internal control achieve?

- Lack of flexibility is an important criticism of a rules-based approach to internal control.

True

False

- What according to COSO are the key characteristics of enterprise risk management?

- What are the key stages of the cybernetic control system?

- Fill in the blank:

…………………………………. risks are risks from which good or harm may result.

- What are the four components of risk management identified by IFAC?

- Fill in the blank:

…………………………………. is the impact of a risk materialising.

- Fill in the blank:

…………………………………. is the overall context of control, the culture, infrastructure and architecture of control, and attitude of directors or managers towards control.

Answers to Quick Quiz

- Facilitate effective and efficient operation by enabling it to respond to significant risks

- Help ensure the quality of internal and external reporting

- Help ensure compliance with applicable laws and regulations

- True

- Process

- Identifies significant events

- Operated by people at every level

- Provides reasonable assurance

- Applied in strategy setting

- Geared to the achievement of objectives

- Applied across the organisation

- Identification of system objectives

- Setting targets for systems objectives

- Measuring achievements/outputs of the system

- Comparing achievements with targets

- Identifying corrective action

- Speculative

Implementing corrective action

- Structure

- Resources

- Culture

- Tools and techniques 7 Hazard

8 Control environment

| Number | Level | Marks | Time |

| Q4 | Examination | 25 | 49 mins |

05 Risk attitudes and internal environment

Study guide

| Intellectual level | ||

| B1 | Management control systems in corporate governance | |

| (d) | Identify, explain and evaluate the corporate governance and executive management roles in risk management (in particular the separation between responsibility for ensuring that adequate risk management systems are in place and the application of risk management systems and practices in the organisation). | 3 |

| (e) | Identify and assess the importance of elements or components of internal control systems. | 3 |

| C1 | Risks and the risk management process | |

| (a) | Define and explain risk in the context of corporate governance. | 2 |

| (b) | Define and describe management responsibilities in risk management. | 2 |

| C3 | Identification, assessment and measurement of risk | |

| (a) | Identify, and assess the impact on, the stakeholders involved in business risk. | 3 |

| D1 | Targeting and monitoring of risk | |

| (a) | Explain and assess the role of a risk manager in identifying and monitoring risk. | 3 |

| (b) | Explain and evaluate the role of the risk committee in identifying and monitoring risk. | 3 |

| D2 | Methods of controlling and reducing risks | |

| (a) | Explain the importance of risk awareness at all levels of an organisation. | 2 |

| (b) | Describe and analyse the concept of embedding risk in an organisation’s systems and procedures. | 3 |

| (c) | Describe and evaluate the concept of embedding risks in an organisation’s culture and values. | 3 |

| D3 | Risk avoidance, retention and modelling | |

| (b) | Explain and evaluate the different attitudes to risk and how these can affect strategy. | 3 |

| (c) | Explain and assess the necessity of incurring risk as part of competitively managing a business organisation. | 3 |

| (d) | Explain and assess attitudes towards risk and the ways in which risk varies in relation to the size, structure and development of an organisation. | 3 |

Exam guide

The chapter contents could be examined in overview or you may be asked more specific questions about various aspects, such as the responsibilities of senior management.

1 Risk and the organisation

| Management responses to risk are not automatic, but will be determined by their own attitudes to risk, which in turn may be influenced by cultural factors. |

FAST FORWARD

1.1 Risk appetite and attitudes 6/14

Remember we mentioned briefly in Chapter 4 that businesses have to take risks in order to develop. Therefore risk-averse businesses are not businesses that are seeking to avoid risks. They are businesses that are seeking to obtain sufficient returns for the risks they take.

Key terms Risk appetite describes the nature and strength of risks that an organisation is prepared to bear.

Risk attitude is the directors’ views on the level of risk that they consider desirable.

Risk capacity describes the nature and strength of risks that an organisation is able to bear.

Different businesses will have different attitudes towards taking risk.

Risk-averse businesses may be willing to tolerate risks up to a point provided they receive acceptable return or, if risk is ‘two-way’ or symmetrical, that it has both positive and negative outcomes. Some risks may be an unavoidable consequence of operating in their business sector. However, there will be upper limits to the risks they are prepared to take whatever the level of returns they can earn.

Risk-seeking businesses are likely to focus on maximising returns and may not be worried about the level of risks that have to be taken to maximise returns (indeed their managers may thrive on taking risks).

The range of attitudes to risk can be illustrated as a continuum. The two ends are two possible extremes, whereas real-life organisations are located between the two. At the left-hand extreme are organisations that never accept any risk and whose strategies are designed to ensure that all risks are avoided. On the right-hand side are organisations that actively accept risks and are risk seeking.

Risk averse Risk seeking

More likely to refuse and More likely to

avoid risk accept risk

Whatever the viewpoint, a business should be concerned with reducing risk where possible and necessary but not eliminating all risks, while managers try to maximise the returns that are possible given the levels of risk. Most risks must be managed to some extent, and some should be eliminated as being outside the business. Risk management under this view is an integral part of strategy, and involves analysing what the key value drivers are in the organisation’s activities, and the risks tied up with those value drivers.

For example, a business in a high-tech industry, such as computing, which evolves rapidly within everchanging markets and technologies, has to accept high risk in its research and development activities, but should it also be speculating on interest and exchange rates within its treasury activities?

Another issue is that organisations that seek to avoid risks (for example public sector companies and charities) do not need the elaborate and costly control systems that a risk-seeking company may have. However, businesses such as those that trade in derivatives, volatile share funds or venture capital companies need complex systems in place to monitor and manage risk. The management of risk needs to be a strategic core competence of the business.

Since risk and return are linked, one consequence of focusing on achieving or maintaining high profit levels may mean that the organisation bears a large amount of risk. The decision to bear these risk levels may not be conscious, and may go well beyond what is considered desirable by shareholders and other stakeholders.

This is illustrated by the experience of the National Bank of Australia, which announced it had lost hundreds of millions of pounds on foreign exchange trading, resulting in share price instability and the resignation of both the Chairman and Chief Executive. In the end the ultimate loss of A$360 million was 110 times its official foreign exchange trading cap of A$3.25 million.

The bank had become increasingly reliant on speculation and high-risk investment activity to maintain profitability. Traders had breached trading limits on 800 occasions and at one stage had unhedged foreign exchange exposures of more than A$2 billion. These breaches were reported internally, as were unusual patterns in trading (very large daily gains) but senior managers took no action. For three years, the currency options team had been the most profitable team in Australia, and had been rewarded by bonuses greater than their annual salaries. Eventually, however, the team came unstuck, and entered false transactions to hide their losses.

The market, however, was unimpressed by the efforts of the bank to make members of the team scapegoats, and market pressure forced changes at the top of the organisation, a general restructuring and a more prudent attitude to risk. Observers, however, questioned whether this change in attitude would survive the economic pressure that the bank was under in the long term.

1.2 Factors influencing risk appetite

Because risk management is bound up with strategy, how organisations deal with risk will not only be determined by events and the information available about events but also by management perceptions of those risks and, as mentioned above, management’s appetite to take risks. These factors will also influence risk culture, the values and practices that influence how an organisation deals with risk in its day-to-day operations.

What therefore influences the risk appetite of managers?

1.3 Personal views

Surveys suggest that managers acknowledge the emotional satisfaction from successful risk taking, although this is unlikely to be the most important influence on appetite. Individuals vary in their attitudes to risk and this is likely to be transferred to their roles in organisations.

Consider a company such as Virgin. It has many stable and successful brands, and healthy cash flows and profits. There’s little need, you would have thought, to consider risky new ventures.

Yet Virgin has a subsidiary called Virgin Galactic to own and operate privately-built spaceships, and to offer ‘affordable’ sub-orbital space tourism to everybody – or everybody willing to pay for the pleasure. The risks are enormous. Developing the project will involve investing very large amounts of money, there is no guarantee that the service is wanted by sufficient numbers of people to make it viable, and the risks of catastrophic accidents are self-evident. In fact a test flight in October 2014 ended in disaster when the rocket broke apart in mid air. The test pilot was killed and the co-pilot was seriously injured.

There is little doubt that Virgin’s risk appetite derives directly from the risk appetite of its chief executive, Richard Branson – a self-confessed adrenaline junkie – who also happens to own most parts of the Virgin Group privately, and so faces little pressure from shareholders.

1.4 Response to shareholder demand

Shareholders demand a level of return that is consistent with taking a certain level of risk. Managers will respond to these expectations by viewing risk taking as a key part of decision-making.

To some extent it must be true that risk appetite is allied to need. If Company A is cash rich in a stable industry with few competitors and satisfied shareholders it has little need to take on any more risky activities. If, a few years later, a significant number of competitors have entered the market and Company A’s profits start to be eroded then it will need to do something to stop the rot, and it will face demands for change from investors.

Failing to take fresh strategic opportunities may be the most significant risk the business faces.

Woolworths in the UK did not fail simply because of the impact of the credit crunch. It had already become irrelevant to its customers – people were no longer sure why they should go to Woolworths. The credit crunch simply speeded up the inevitable result of catastrophic strategic wearout. Woolworths had continued to offer the same products to the same customers despite the changing customer and competitor landscape.

1.5 Organisational influences

Organisational influences may be important, and these are not necessarily just a response to shareholder concerns. Organisational attitudes may be influenced by significant losses in the past, changes in regulation and best practice, or even changing views of the benefits that risk management can bring.

Attitudes to risk will also depend on the size, structure and stage of development of the organisation.

- Size of organisation

A larger organisation is likely to require more formal systems and will have to take account of varying risk appetites and incidence among its operations. However, a large organisation will also be able to justify employing risk specialists, either generally or in specific areas of high risk, such as treasury. It is also more likely to be able to diversify its activities so that it is not dependent on a few products.

- Structure

The risk management systems employed will be dependent on the organisation’s management control systems that will in turn depend on the formality of structure, the autonomy given to local operations and the degree of centralisation deemed desirable.

- Attitudes to risk

Attitudes to risk will change as the organisation develops and its risk profile changes. For example, attitudes to financial risk and gearing will change as different sources of finance become necessary to fund larger developments.

Unsurprisingly there are particularly onerous responsibilities on trustees of charities. The UK’s Good Governance: A Code for the Voluntary and Community Sector stresses that trustees must exercise special care when investing the organisation’s funds, or borrowing funds for it to use, and must comply with the organisation’s governing document and any other legal requirements.

1.6 National influences

There is some evidence that national culture influences attitudes towards risk and uncertainty. Surveys suggest that attitudes to risk vary nationally according to how much people are shielded from the consequences of adverse events.

Risk taking: is it behavioural, genetic, or learned?

Behaviour of individuals

Risky business has never been more popular. Mountain climbing is among the fastest-growing sports. Extreme skiing – in which skiers descend cliff-like runs by dropping from ledge to snow-covered ledge – is drawing ever-wider interest. The adventurer-travel business, which often mixes activities like climbing or river rafting with wildlife safaris, has grown into a multimillion-dollar industry.

Under conventional personality theories, normal individuals do everything possible to avoid tension and risk, and in the not too distant past, students of human behaviour might have explained such activities as an abnormality, a kind of death wish. But in fact researchers are discovering that the psychology of risk involves far more than a simple ‘death wish’. Studies now indicate that the inclination to take high risks may be hard-wired into the brain, intimately linked to arousal and pleasure mechanisms, and may offer such a thrill that it functions like an addiction. The tendency probably affects one in five people, mostly young males, and declines with age.

It may ensure our survival, even spur our evolution as individuals and as a species. Risk taking probably bestowed a crucial evolutionary advantage, inciting the fighting and foraging of the hunter-gatherer.

In mapping out the mechanisms of risk, psychologists hope to do more than explain why people climb mountains. Risk taking, which one researcher defines as ‘engaging in any activity with an uncertain outcome’, arises in nearly all walks of life.

Asking someone on a date, accepting a challenging work assignment, raising a sensitive issue with a spouse or a friend, confronting an abusive boss – these all involve uncertain outcomes, and present some level of risk.

High risk takers

Researchers don’t yet know precisely how a risk-taking impulse arises from within or what role is played by environmental factors, from upbringing to the culture at large. And, while some level of risk taking is clearly necessary for survival (try crossing a busy street without it!), scientists are divided as to whether, in a modern society, a ‘high-risk gene’ is still advantageous.

Some scientists see a willingness to take big risks as essential for success, but research has also revealed the darker side of risk taking. High-risk takers are easily bored and may suffer low job satisfaction. Their craving for stimulation can make them more likely to abuse drugs, gamble, commit crimes and be promiscuous.

Indeed, this peculiar form of dissatisfaction could help explain the explosion of high-risk sports in postindustrial Western nations. In unstable cultures, such as those at war or suffering poverty, people rarely seek out additional thrills. But in rich and safety-obsessed countries, full of guardrails and seat belts, and with personal-injury claims companies swamping TV advertising, everyday life may have become too safe, predictable and boring for those programmed for risk taking.

Until recently, researchers were baffled. Psychoanalytic theory and learning theory relied heavily on the notion of stimulus reduction, which saw all human motivation geared towards eliminating tension. Behaviours that created tension, such as risk taking, were deemed dysfunctional, masking anxieties or feelings of inadequacy.

Yet as far back as the 1950s, research was hinting at alternative explanations. British psychologist Hans J Eysenck developed a scale to measure the personality trait of extroversion, now one of the most consistent predictors of risk taking. Other studies revealed that, contrary to Freud, the brain not only craved arousal but also somehow regulated that arousal at an optimal level. Researchers have extended these early findings into a host of theories about risk taking.

Some scientists concentrate on risk taking primarily as a cognitive or behavioural phenomenon, an element of a larger personality dimension which measures individuals’ sense of control over their environment and their willingness to seek out challenges.

A second line of research focuses on risk’s biological roots. Due to relatively low levels of certain enzymes and neurotransmitters the cortical system of a risk taker can handle higher levels of stimulation without overloading and switching to the fight or flight response. Their brains automatically dampen the level of incoming stimuli, leaving them with a kind of excitement deficit. The brains of people who don’t like taking risks, by contrast, tend to augment incoming stimuli, and thus desire less excitement.

Even then, enzymes are only part of the risk-taking picture. Upbringing, personal experience, socioeconomic status and learning are all crucial in determining how that risk-taking impulse is ultimately expressed. For many climbers their interest in climbing was often shaped externally, either through contact with older climbers or by reading about great expeditions. On entering the sport, novices are often immersed in a tight-knit climbing subculture, with its own lingo, rules of conduct and standards of excellence.

This learned aspect may be the most important element in the formation of the risk-taking personality.

This is much abridged and somewhat adapted from an article in Psychology Today.

Behaviour of organisations

To what extent can these ideas be applied to organisations? The case study indicates that the tendency to take risks or not depends on cognitive psychological factors (willingness to take on challenges) and genetic factors (the relative absence of certain chemicals in the brain that suppress the fear that most people feel when confronted with risk). None of this makes much sense when talking about an abstract non-living thing like a company, which exists only on paper and in the eyes of the law.

However, the case study also indicates that upbringing, personal experience, socioeconomic status and learning play a part and that risk takers tend to be immersed in a subculture with its own language, rules of conduct and standards of excellence.

Equally, organisations have a history and have unique experiences, and are wealthy or struggling. They set rules of conduct and standards of excellence. Their people possess knowledge and talk in organisational jargon. This is commonly called the organisation’s culture.

Exam focus In December 2008 Question 1 the differing approaches to a business decision could be distinguished by point the risks involved. If you are asked to analyse any business decision, you need to think carefully about the risk implications.

2 Impact of risk on stakeholders

FAST FORWARD Organisations’ attitudes to risks will be influenced by the priorities of their stakeholders and how much influence stakeholders have. Stakeholders that have significant influence may try to prevent an organisation bearing certain risks.

2.1 Stakeholders’ attitudes to risk

Businesses have to be aware of stakeholder responses to risk – the risk that organisations will take actions or events will occur that will generate a response from stakeholders that has an adverse effect on the business.

To assess the importance of stakeholder responses to risk, the organisation needs to determine how much leverage its stakeholders have over it. As we have seen, Mendelow provides a mechanism for classifying stakeholders.

2.2 Shareholders

They can affect the market price of shares by selling them or they have the power to remove management. It would appear that the key issue for management to determine is whether shareholders:

- Prefer a steady income from dividends (in which case they will be alert to threats to the profits that generate the dividend income, such as investment in projects that are unlikely to yield profits in the short term)

- Are more concerned with long-term capital gains, in which case they may be less concerned about a short period of poor performance, and more worried about threats to long-term survival that could diminish or wipe out their investment

2.2.1 Risk tolerances of shareholders

However, the position is complicated by the different risk tolerances of shareholders themselves. Some shareholders will, for the chances of higher level of income, be prepared to bear greater risks that their investments will not achieve that level of income. Therefore some argue that because the shares of listed companies can be freely bought and sold on stock exchanges, if a company’s risk profile changes, its existing shareholders will sell their shares, but the shares will be bought by new investors who prefer the company’s new risk profile. The theory runs that it should not matter to the company who its investors are. However, this makes the assumption that the investments of all shareholders are actively managed and that shareholders seek to reduce their own risks by diversification. This is not necessarily true in practice.

In addition, we have seen that the corporate governance reports have stressed the importance of maintaining links with individual shareholders. It is therefore unlikely that the directors will be indifferent to who the company’s shareholders are.

Shareholders’ risk tolerance may depend on their views of the organisation’s risk management systems, how effective they are and how effective they should be. Shareholder sensitivity to this will increase the pressures on management to ensure that a risk culture is embedded within the organisation (covered later in this chapter).

2.3 Debt providers and creditors

Debt providers are most concerned about threats to the amount the organisation owes and can take various actions with potentially serious consequences, such as denial of credit, higher interest charges or ultimately putting the company into liquidation.

When an organisation is seeking credit or loan finance, it will obviously consider what action creditors will take if it does default. However, it also needs to consider the ways in which debt finance providers can limit the risks of default by for example requiring companies to meet certain financial criteria or provide security in the form of assets that can’t be sold without the creditors’ agreement or personal guarantees from directors.

These mechanisms may have a significant impact on the development of an organisation’s strategy. There may be a conflict between strategies that are suitable from the viewpoint of the business’s long-term strategic objectives, but are unacceptable to existing providers of finance because of threats to cash flows, or are not feasible because finance suppliers will not make finance available for them, or will do so on terms that are unduly restrictive.

2.4 Employees

Employees will be concerned about threats to their job prospects (money, promotion, benefits and satisfaction) and ultimately threats to the jobs themselves. If the business fails, the impact on employees will be great. However, if the business performs poorly, the impact on employees may not be so great if their jobs are not threatened.

Employees will also be concerned about threats to their personal wellbeing, particularly health and safety issues.

The variety of actions employees can take would appear to indicate the risk is significant. Possible actions include pursuit of their own goals rather than shareholder interests, industrial action, refusal to relocate or resignation.

Risks of adverse reactions from employees will have to be managed in a variety of ways.

- Risk avoidance – legislation requires that some risks, principally threats to the person, should be avoided

- Risk reduction – limiting employee discontent by good pay, conditions, etc

- Risk transfer – for example taking out insurance against key employees leaving

- Risk acceptance – accepting that some employees will be unhappy but believing the company will

not suffer a significant loss if they leave

2.5 Customers and suppliers

Suppliers can provide (possibly unwillingly) short-term finance. As well as being concerned with the possibility of not being paid, suppliers will be concerned about the risk of making unprofitable sales. Customers will be concerned with threats to their getting the goods or services that they have been promised, or not getting the value from the goods or services that they expect.

The impact of customer-supplier attitudes will partly depend on how much the organisation wants to build long-term relationships with them. A desire to build relationships implies involvement of the staff that are responsible for building those relationships in the risk management process. It may also imply a greater degree of disclosure about risks that may arise to the long-term partners in order to maintain the relationship of trust.

2.6 The wider community

Governments, regulatory and other bodies will be particularly concerned with risks that the organisation does not act as a good corporate citizen, implementing for example poor employment or environmental policies. A number of the variety of actions that can be taken could have serious consequences. Government can impose tax increases or regulation or take legal action. Pressure groups tactics can include publicity, direct action, sabotage or pressure on government.

Although the consequences can be serious, the risks that the wider community are concerned about can be rather less easy to predict than for other stakeholders being governed by varying political pressures. This emphasises the need for careful monitoring as part of the risk management process, of changing attitudes and likely responses to the organisation’s actions.

3 Internal environment

FAST FORWARD

The internal or control environment is influenced by management’s attitude towards control, the organisational structure and the values and abilities of employees.

| 3.1 Nature of internal environment | 12/14 |

Key terms The internal or control environment is the overall attitude, awareness and actions of directors and

management regarding internal controls and their importance in the entity. The internal environment encompasses the management style, and corporate culture and values shared by all employees. It provides the background against which the various other controls are operated.

COSO’s guidance stresses that a strong commitment at the top of the organisation to sound control compliance, integrity and ethical values is essential for a sound control framework to exist. It may be easier in smaller companies for senior managers to reinforce the companies’ values and oversee staff, as they are more likely be in close day-to-day contact with staff.

One aspect of a poor control environment would be managers viewing control as an administrative burden, bolted on to existing systems. Instead there needs to be recognition of the business need for, and the benefit from, internal control that is effectively integrated with core processes.

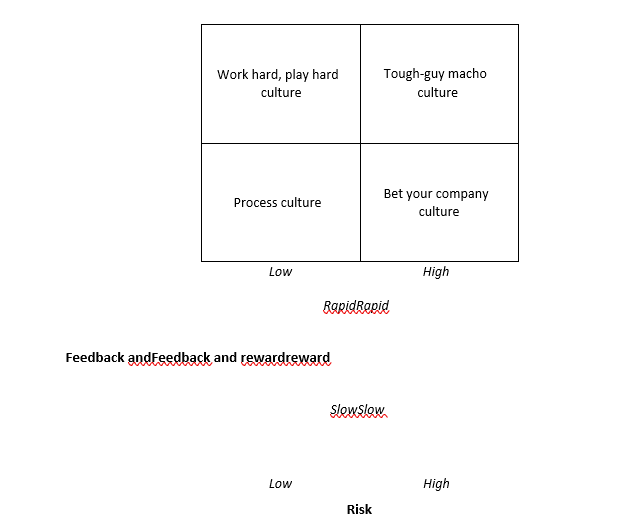

The following factors are reflected in the internal environment.

- The philosophy and operating style of the directors and management

- The entity’s culture; whether control is seen as an integral part of the organisational framework, or something that is imposed on the rest of the system

- The entity’s organisational structure and methods of assigning authority and responsibility

(including segregation of duties and supervisory controls)

- The directors’ methods of imposing control, including the internal audit function, the functions of the board of directors and personnel policies and procedures

- The integrity, ethical values and competence of directors and staff

The UK Turnbull report highlighted a number of elements of a strong internal environment.

- Clear strategies for dealing with the significant risks that have been identified

- The company’s culture, code of conduct, processes and structures, human resource policies and performance reward systems supporting the business objectives and risk management and internal control systems

- Senior management demonstrating through its actions and policies commitment to competence, integrity and fostering a climate of trust within the company

- Clear definition of authority, responsibility and accountability so that decisions are made and actions are taken by the appropriate people

- Communication to employees of what is expected of them and the scope of their freedom to act

- People in the company having the knowledge, skills and tools to support the achievements of the organisation’s objectives and to manage its risks effectively

However, a strong internal environment does not, by itself, ensure the effectiveness of the overall internal control system although it will have a major influence on it.

The internal environment will have a major impact on the establishment of business objectives, the structuring of business activities and dealing with risks.

3.2 Internal environment and financial reporting