Introduction

We start this Text by discussing corporate governance, a fundamental topic in this

paper. You have encountered corporate governance already in your law and auditing

studies, but this syllabus requires a deeper understanding of what has driven the

development of corporate governance codes over the last 15 years.

We start by looking at the principles that underpin corporate governance codes. Some

will be familiar from what you have learnt about ethics in auditing. We shall examine

ethics in detail in Part C of this Text, but you’ll find that certain ethical themes recur

throughout this book.

In Section 2 we show how corporate governance has partly developed in response to

the problem of agency – the difficulty of ensuring that shareholders are able to

exercise sufficient control over directors and managers, their agents. In Section 3 we

consider the interests of other stakeholders in corporate governance. As we shall see

in later chapters, a key issue in the development of corporate governance is how

much, if at all, directors/managers have a responsibility to consider the interests of

stakeholders other than shareholders. The examiner has stressed the need for

understanding that business decisions are affected by, and can affect, many people

inside and outside the business.

In the last section we introduce other major corporate governance issues. We shall

see how corporate governance guidelines address these in the next two chapters.

Study guide

| Intellectual level | ||

| A1 | The scope of governance | |

| (a) | Define and explain the meaning of corporate governance. | 2 |

| (b) | Explain and analyse the issues raised by the development of the joint stock company as the dominant form of business organisation and the separation of ownership and control over business activity. | 3 |

| (c) | Analyse the purpose and objectives of corporate governance in the public and private sectors. | 2 |

| (d) | Explain and apply in the context of corporate governance the key underpinning concepts. | 3 |

| (e) | Explain and assess the major areas of organisational life affected by issues in corporate governance. | 3 |

| (f) | Compare and distinguish between public, private and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) with regard to the issues raised by, and the scope of, governance. | 3 |

| (g) | Explain and evaluate the roles, interests and claims of the internal parties involved in corporate governance. | 3 |

| (h) | Explain and evaluate the roles, interests and claims of the external parties involved in corporate governance. | 3 |

| (i) | Analyse and discuss the role and influence of institutional investors in corporate governance systems and structures, for example the roles and influences of pension funds, insurance companies and mutual funds. | 2 |

| A2 | Agency relationships and theories | |

| (a) | Define and explore agency theory. | 2 |

| (b) | Define and explain the key concepts in agency theory. | 2 |

| (c) | Explain and explore the nature of the principal-agent relationship in the context of corporate governance. | 3 |

| (d) | Analyse and critically evaluate the nature of agency accountability in agency relationships. | 3 |

| (e) | Explain and analyse the following other theories used to explain aspects of the agency relationship: Transactions cost theory and Stakeholder theory. | 2 |

| A7 | Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility | |

| (b) | Discuss and critically assess the concept of stakeholder power and interest using the Mendelow model and how this can affect strategy and corporate governance. | 3 |

Exam guide

You may be asked about the significance of the underlying concepts in Section 1, or to analyse a corporate governance scenario in terms of the agency responsibilities directors or auditors have towards various stakeholders, given the claims the stakeholders have on the organisation. Questions may also examine the roles of other participants in corporate governance. Questions will not always be about listed companies. They will also cover public sector organisations and charities. The issues highlighted in the last section could well be important problems in a scenario question. To quote the examiner: ‘Most questions will involve some focus on, or connection with, the stakeholders and how their agents act on their behalf. Students will have to identify the relevant stakeholders primarily by assessing their power and interest.’

1 Definitions of corporate governance 12/12, 12/14, 6/15

| Corporate governance, the system by which organisations are directed and controlled, is based on a number of concepts, including transparency, independence, accountability and integrity. |

FAST FORWARD

1.1 What is corporate governance?

| Corporate governance is the system by which organisations are directed and controlled. (Cadbury report)

Corporate governance is a set of relationships between a company’s directors, its shareholders and other stakeholders. It also provides the structure through which the objectives of the company are set, and the means of achieving those objectives and monitoring performance, are determined. (OECD) |

Key term

Exam focus An exam question on corporate governance might start by asking you to define what corporate point governance is.

A number of comments can be made about these definitions of corporate governance.

- The management, awareness, evaluation and mitigation of risk are fundamental in all definitions of good governance. This includes the operation of an adequate and appropriate system of control.

- The notion that overall performance is enhanced by good supervision and management within set best practice guidelines underpins most definitions.

- Good governance provides a framework for an organisation to pursue its strategy in an ethical and effective way and offers safeguards against misuse of resources, human, financial, physical or intellectual.

- Good governance is not just about externally established codes; it also requires a willingness to apply the spirit as well as the letter of the law.

- Good corporate governance can attract new investment into companies, particularly in developing nations. It should mean that shareholders can trust those responsible for running and monitoring the company.

- Accountability is generally a major theme in all governance frameworks, including accountability not just to shareholders but also to other stakeholders, and accountability not just by directors but by auditors as well.

- Corporate governance underpins capital market confidence in companies and in the government/regulators/tax authorities that administer them. It helps protect the value of shareholders’ investment.

1.1.1 History of governance

Governance focuses on ownership because ownership, and therefore financing, results in businesses being formed and expanded. Different systems of governance are seen as best practice in different countries, as we shall see later in this text. However, much of the governance debate has been seen in the context of the so-called Anglo-Saxon model where ownership and management are separate, and companies can obtain a listing on a stock exchange where their shares are bought and sold.

1.1.2 Governance in companies and non-governmental organisations

Although mostly discussed in relation to large quoted companies, governance is an issue for all corporate bodies, commercial and not for profit, including public sector and non-governmental organisations. There are certain ways in which companies might differ from other types of organisation, such as their ownership (principals), their mission and the legal/regulatory environment within which they operate.

Public sector organisations are organisations that are controlled by one or more parts of the state. Their functions are often to implement government policy in secretarial or administration areas. Some are supervised by government departments (for example hospitals or schools). Others are devolved bodies, such as local authorities, nationalised companies (majority or all of the shares owned by the Government), supranational bodies or non-governmental organisations.

These organisations are in the public sector because the control over a particular public service, utility or public good is seen as so important that it cannot be left to the profit-motivated sector, which may for example seek to close socially vital loss-making services, such as bus routes.

Objectives will be determined by the political leaders in line with government policy. They are likely to focus on value for money and service delivery objectives, possibly underpinned by legislation. The level of control may be high, leading to accusations of excess bureaucracy and cost.

In many countries there are thousands of charities and voluntary organisations that exist to fulfil a particular purpose, maybe social, environmental, religious or humanitarian. Funds are raised to support that purpose. Charities are not owned as such, but will be primarily responsible to the donors of funds and the beneficiaries (those who receive money or other aid) out of the charities’ resources. Charities will be subject to their own legal regime that grants privileges (for example tax concessions) but imposes requirements on how funds can be spent and the charities’ assets managed.

As well as being crucial to passing P1, you also need to be able to demonstrate your contribution to effective and appropriate governance in your area of responsibility in order to fulfil performance objective 4 of your PER.

1.2 Corporate governance concepts

One view of governance is that it is based on a series of underlying concepts.

1.2.1 Fairness

The directors’ deliberations and also the systems and values that underlie the company must be balanced by taking into account everyone who has a legitimate interest in the company, and respecting their rights and views. In many jurisdictions, corporate governance guidelines reinforce legal protection for certain groups, for example minority shareholders. It should mean the company deals even-handedly with others.

1.2.2 Transparency 12/07, 12/08, 6/11, 6/13, 6/14

| Transparency means open and clear disclosure of relevant information to shareholders and other stakeholders, as well as not concealing information when it may affect decisions. It means open discussions and a default position of information provision rather than concealment. |

Key term

Disclosure in this context obviously includes information in the financial statements, not just the numbers and notes to the accounts but also narrative statements such as the directors’ report and the operating and financial or business review. It also includes all voluntary disclosure; that is, disclosure above the minimum required by law or regulation. Voluntary corporate communications include management forecasts, analysts’ presentations, press releases, information placed on websites and other reports such as standalone environmental or social reports.

The main reason why transparency is so important relates to the agency problem that we shall discuss in Section 2, the potential conflict between owners and managers. Without effective disclosure the position could be unfairly weighted towards managers, since they have far more knowledge of the company’s activities and financial situation than the owner/investors. Avoidance of this information asymmetry requires not only effective disclosure rules but also strong internal controls that ensure the information that is disclosed is reliable. Information also needs to be published in sufficient detail to meet the needs of shareholders/owners. Publication of abbreviated information may be counter-productive and may give the impression of concealment rather than openness.

Linked with the agency issue, publication of relevant and reliable information reassures investors and underpins stock market confidence in how companies are being governed and thus significantly influences market prices. International accounting standards and stock market regulations based on corporate governance codes require information published to be true and fair. Information can only fulfil this requirement if adequate disclosure is made of uncertainties and adverse events. It is therefore clear that financial data will be insufficient without supporting explanation.

Circumstances where concealment may be justified include discussions about future strategy (knowledge of which would benefit competitors), confidential issues relating to individuals and discussions leading to an agreed position that is then made public.

Ethics guru Chris Macdonald has raised a number of issues with the concept of transparency.

- The requirement of transparency to check how directors (agents) are doing indicates a big problem with governance. If shareholders had complete confidence in directors, there would be no concern about transparency.

- Transparency assumes that those who receive information are well informed but problems may arise through misinterpretation. The example quoted was a hospital executive being criticised for having the perk of expensive membership of an exclusive private club. However, if the executive was responsible for fundraising, the club would provide networking opportunities with members who could make large donations to the hospital.

- In the context of directors’ remuneration (discussed in Chapter 3) evidence suggests that full transparency can ratchet up average reward. A chief executive, seeing how much other chief executives in their sector are earning, may want their rewards to match theirs. A remuneration committee may regard the fact that its chief executive is earning below average remuneration as poor publicity for the chief executive and the company.

- Full transparency of rewards of one type may lead to those in positions of trust to seek less visible, and perhaps more costly, rewards. For example, the 2009 scandal about excessive expenses being claimed by UK Members of Parliament was linked to the political unacceptability of increasing MPs’ salaries significantly. To head off a revolt by members, the Conservative Government in the 1980s introduced a big increase in members’ expense allowances, with the minister responsible allegedly telling MPs ‘go out boys and spend it.’

| Weighing up transparency against confidentiality may be difficult and hence the examiner tests it regularly. Remember that sometimes there may be valid commercial reasons for keeping information away from those who may use it against the company. On the other hand, greater transparency and providing a full explanation for controversial actions can be an effective means of responding to critics. |

Exam focus point

1.2.3 Innovation

The concept of innovation in the approach to corporate governance recognises the fact that the needs of businesses and stakeholders can change over time. It also has an impact on how organisations respond to meeting the ‘comply or explain’ requirement contained in various codes of corporate governance that are currently in effect.

1.2.4 Scepticism

The UK Corporate Governance Code, under the heading of ‘Leadership’, encourages non-executive directors (NEDs) to adopt an air of scepticism so that they can effectively challenge management decisions in their role of scrutiny. Applying professional scepticism is also an important part of the role of auditors and audit committees. ISA 200 defines professional scepticism as: ‘An attitude that includes a questioning mind, being alert to conditions which may indicate possible misstatement due to error or fraud, and a critical assessment of audit evidence.’ This does not mean that all management decisions and evidence have to be approached with suspicion or mistrust; but rather that an open and enquiring mind must always be employed. A healthy corporate culture and environment is one that encourages and enables such scepticism to thrive.

1.2.5 Independence

| Independence is the avoidance of being unduly influenced by vested interests and free from any constraints that would prevent a correct course of action being taken. It is an ability to stand apart from inappropriate influences and be free of managerial capture, to be able to make the correct and uncontaminated decision on a given issue.

Independence is a quality that can be possessed by individuals and is an essential component of professionalism and professional behaviour. |

Key term

An important distinction generally with independence is independence of mind and independence of appearance.

- Independence of mind means providing an opinion without being affected by influences compromising judgement.

- Independence of appearance means avoiding situations where an informed third party could reasonably conclude that an individual’s judgement would have been compromised.

Independence is an important concept in relation to directors; in particular, freedom from conflicts of interest. Corporate governance reports have increasingly stressed the importance of independent nonexecutive directors, directors who are not primarily employed by the company and who have very strictly controlled other links with it. They should be in a better position to promote the interests of shareholders and other stakeholders. Freed from pressures that could influence their activities, independent nonexecutive directors should be able to carry out effective monitoring of the company and its management in conjunction with equally independent external auditors on behalf of shareholders.

Non-executive directors’ lack of links and limits on the time that they serve as non-executive directors should promote avoidance of managerial capture – accepting executive managers’ views on trust without analysing and questioning them.

As you will remember from Paper F8, the independence of external auditors from their clients is also important in corporate governance (covered further in Chapter 10). As the auditor is acting on behalf of the shareholders and not the client, close friendship with the client may influence the external auditor’s judgement, and mean that the external auditor is not effectively representing the shareholders’ interests. Internal auditors also need to be independent of the colleagues whom they are auditing (discussed in Chapter 8).

A complication when considering independence is that there are varying degrees of independence, lying between total independence (no knowledge/connection with the other party) and zero independence

(inability to take a decision without considering the effect on the other party). In real-life situations the two extremes are unlikely, but in most situations independence should be as near to total independence as possible.

|

|||||||||

- Shareholders and other stakeholders need a trustworthy record of directors’ stewardship to be able to take decisions about the company. Assurance provided by independent auditors is a key quality control on reliability.

- An unqualified report by independent external auditors on the accounts should give them more credibility, enhancing the appeal of the company to investors.

- A lack of independence may mean that an effective audit is not done. Thus the shareholders are not receiving value for the costs of the audit.

- A lack of independence may lead to a failure to fulfil professional requirements. Failure to do this undermines the credibility of the accountancy profession and the standards it enforces.

1.2.6 Probity/honesty

Hopefully this should be the most self-evident of the principles. It relates to not only telling the truth but also not misleading shareholders and other stakeholders. Lack of probity includes not only obvious examples of dishonesty, such as taking bribes, but also reporting information in a slanted way that is designed to give an unfair impression.

Guidance in the UK charitable sector has defined probity in terms of receipt of gifts or hospitality by trustees. The Code stresses that all gifts should be clearly recorded, and trustees should not accept gifts with a significant monetary value or lavish hospitality. They should certainly not accept gifts or hospitality which may seem likely to influence their decisions.

1.2.7 Responsibility

Responsibility means management accepting the credit or blame for governance decisions. It implies clear definition of the roles and responsibilities of the roles of senior management.

The South African King report stresses that, for management to be held properly responsible, there must be a system in place that allows for corrective action and penalising mismanagement. Responsible management should do, when necessary, whatever it takes to set the company on the right path.

King states that the board of directors must act responsively to, and with responsibility towards, all stakeholders of the company. However, the responsibility of directors to other stakeholders, both in terms of to whom they are responsible and the extent of their responsibility, remains a key point of contention in corporate governance debates. We shall discuss the importance of stakeholders later in this chapter.

The limits of responsibility and how responsibility is enforced will be a recurring theme throughout this text, developed further in:

- Chapters 2-3, on corporate governance

- Chapters 4-8, covering directors’ responsibilities in respect of risk management and internal control

- Chapters 9-10, covering accountants’ responsibilities to clients and society

- Chapter 11, covering corporate social responsibility

1.2.8 Accountability 12/12

| Corporate accountability refers to whether an organisation (and its directors) is answerable in some way for the consequences of its actions. |

Key term

Directors being answerable to shareholders have always been an important part of company law, well before the development of the corporate governance codes. For example, companies in many regimes have been required to provide financial information to shareholders on an annual basis and hold annual general meetings. However, particularly because of the corporate governance scandals of the last 30 years, investors have demanded greater assurance that directors are acting in their interests. This has led to the development of corporate governance codes, which we shall consider in the next chapter.

Making accountability work is the responsibility of both parties. Directors, as we have seen, do so through the quality of information that they provide whereas shareholders do so through their willingness to exercise their responsibility as owners, which means using the available mechanisms to query and assess the actions of the board. Public sector accountability

The accountability relationship will be different for bodies owned or run by national or central government. The nature of the relationship may be clear – that government determines objectives. How accountability is demonstrated and enforced may depend though on how coherent the objectives are. The main problem will often be where the body’s main objectives are non-economic, but the Government also wishes to limit the amount it spends on the body.

As with responsibility, one of the biggest debates in corporate governance is the extent of management’s accountability towards other stakeholders, such as the community in which the organisation operates. This has led on to a debate that we shall discuss in Chapter 10 about the contents of accounts themselves.

In the context of public service, the UK Nolan Committee on Standards in Public Life commented that holders of public office are accountable for their decisions and actions to the public, and must submit themselves to whatever scrutiny is appropriate for their office.

A wider issue with the extent of accountability in the public sector is the extent of accountability towards different groups in society. For example, politicians can be seen as being accountable to the body of taxpayers as a whole – it is their interests that parliamentary bodies have been established to represent. However, politicians are also accountable to a group within the category of taxpayers – the voters who voted for them. This raises the issue of what happens if the actions politicians take advantage their voters, but disadvantage other taxpayers. More controversially, there is the issue of the extent to which politicians should be accountable to donors who pay significant sums to finance their political activities.

| The examiner has commented:

‘When I say accountability, I mean companies to investors, professionals to their values, business systems to their stakeholders and so forth.’ These comments emphasise that accountability, like responsibility, is a topic that underpins much of the rest of this text and will be a key feature in many exam questions. The comments indicate that it is possible to be accountable to an abstract set of values. However, much of the discussion about accountability focuses on the extent of accountability to stakeholders, particularly when stakeholder interests differ. |

Exam focus point

Reputation 6/14

Reputation is determined by how others view a person, organisation or profession. Reputation includes a reputation for competence, supplying good quality goods and services in a timely fashion, and also being managed in an orderly way. However, a poor ethical reputation can be as serious for an organisation as a poor reputation for competence.

The consequences of a poor reputation for an organisation can include:

- Suppliers’ and customers’ unwillingness to deal with the organisation for fear of being victims of sharp practice

- Inability to recruit high-quality staff

- Fall in demand because of consumer boycotts

- Increased public relations costs because of adverse stories in the media

- Increased compliance costs because of close attention from regulatory bodies or external auditors

- Loss of market value because of a fall in investor confidence

Over the past few years the American retail giant Wal-Mart has made efforts to improve its reputation in various ways. These have included improving its labour and healthcare records, donating to not for profit organisations and promoting the case that it helps economic growth and provides healthy groceries. This has partly been for strategic purposes, as the company has sought to open stores in cities in face of local hostility, due to the adverse effect on other local retailers.

Unfortunately Wal-Mart’s attempts to portray itself as more ethical have been undermined by a recent bribery scandal, as we shall see in Chapter 10.

We shall see later on in this Text how risks to an organisation’s reputation depend on how likely other risks are to crystallise.

In the context of governance, reputation also means personal and professional reputation, and the moral reputation of the accountancy profession as a whole. All are influenced by the extent to which individuals or members of the profession demonstrate the other underlying concepts we have discussed.

1.2.10 Judgement 6/14

Judgement means the board making decisions that enhance the prosperity of the organisation. This means that board members must acquire a broad enough knowledge of the business and its environment to be able to provide meaningful direction to it. This has implications not only for the attention directors have to give to the organisation’s affairs, but also on the way the directors are recruited and trained.

As you will see when you come to study Paper P3, the complexities of senior management mean that the directors have to bring multiple conceptual skills to management that aim to maximise long-term returns. This means that corporate governance can involve balancing many competing people and resource claims against each other. Although, as we shall see, risk management is an integral part of corporate governance, corporate governance isn’t just about risk management.

1.2.11 Integrity 6/10, 06/13

Key term ‘Integrity means straightforward dealing and completeness. What is required of financial reporting is that

it should be honest and that it should present a balanced picture of the state of the company’s affairs. The integrity of reports depends on the integrity of those who prepare and present them.’ (Cadbury report)

Integrity (means that) holders of public office should not place themselves under any financial or other obligation to outside individuals or organisations that might influence them in the performance of their

official duties. UK Nolan Committee Standards on Public Life

Integrity can be taken as meaning someone of high moral character, who sticks to strict moral or ethical principles no matter the pressure to do otherwise. In working life this means adhering to the highest standards of professionalism and probity. Straightforwardness, fair dealing and honesty in relationships with the different people and constituencies whom you meet are particularly important. Trust is vital in relationships and belief in the integrity of those with whom you are dealing underpins this.

Integrity is an underlying principle of corporate governance. All those in agency relationships should possess and exercise absolute integrity. To fail to do so breaches the relationship of trust. The Cadbury report definition highlights the need for personal honesty and integrity of preparers of accounts. This implies qualities beyond a mechanical adherence to accounting or ethical regulations or guidelines. At times accountants will have to use judgement or face financial situations which aren’t covered by regulations or guidance, and on these occasions integrity is particularly important.

Integrity is an essential principle of the corporate governance relationship, particularly in relationship to representing shareholder interests and exercising agency (discussed in Section 2). Monitoring and hence agency costs can be reduced if there is trust in the integrity of the agents. In addition, we have seen that a key aim of corporate governance is to inspire confidence in participants in the market and this significantly depends on a public perception of competence and integrity.

Integrity is also one of the fundamental principles discussed in the IESBA code of ethics (see Chapter 10). It provides assurance to those with whom the accountant deals of good intentions and truthfulness.

Exam focus The Pilot Paper asks for an explanation of what integrity is, and its importance in corporate governance.

point The December 2007 exam asked about the significance of transparency. The June 2013 exam had a question about the importance of integrity and transparency. You may be asked similar questions about other principles.

2 Corporate governance and agency theory 6/08, 6/09, 6/10

FAST FORWARD

Agency is extremely important in corporate governance, as the directors/managers are often acting as agents for the owners. Corporate governance frameworks aim to ensure directors/managers fulfil their responsibilities as agents by requiring disclosure and suggesting they be rewarded on the basis of performance.

| 2.1 Nature of agency | 12/14, 6/15 |

Key term Agency relationship is a contract under which one or more persons (the principals) engage another

person (the agent) to perform some service on their behalf that involves delegating some decision-making

authority to the agent. (Jensen and Meckling)

You will have encountered agency in your earlier studies, but a brief revision will be helpful. There are a number of specific types of agent. These have either evolved in particular trades or developed in response to specific commercial needs. Examples include factors, brokers, estate agents, bankers and auctioneers.

Agency in the context of director-shareholder relationships is discussed below. However, there are many other types of agency relationships. Corporate governance guidance is concerned with the shareholderauditor agency relationship as well as the shareholder-manager relationship. The auditors act as the shareholders’ agents when carrying out an audit, and thus the shareholders wish them to maintain their independence of the management of the company being audited. The problems auditors have when attempting to maintain their independence is dealt with in governance guidance.

Exam focus Question 1 in June 2009 asked about the agency relationship between a bank and the trustees of a point pension fund that invested in the bank. However, not all organisations have private shareholders/investors. June 2010 Question 1 examined the agency situation in a nationalised company wholly owned by the home country government. Not only the Government but also the taxpayers are principals there. Managers running a charity will be acting as agents for the trustees who represent the principals (donors and recipients of aid). In December 2013 there was a question requiring a definition of agency in the context of corporate governance.

2.2 Accountability and fiduciary responsibilities

2.2.1 Accountability

Key term In the context of agency, accountability means that the agent is answerable under the contract to their principal and must account for the resources of their principal and the money they have gained working on their principal’s behalf.

Two problems potentially arise with this.

- How does the principal enforce this accountability (the agency problem, see below)? As we shall see, the corporate governance systems developed to monitor the behaviour of directors have been designed to address this issue.

- What if the agent is accountable to parties other than their principal – how do they reconcile possibly conflicting duties (for the stakeholder view see Section 3)?

2.2.2 Fiduciary duty 06/13

| Fiduciary duty is a duty of care and trust which one person or entity owes to another. It can be a legal or ethical obligation. In law it is a duty imposed on certain persons because of the position of trust and confidence in which they stand in relation to another. The duty is more onerous than generally arises under a contractual or tort relationship. It requires full disclosure of information held by the fiduciary, a strict duty to account for any profits received as a result of the relationship, and a duty to avoid conflicts of interest.

|

Key term

Under English law company directors owe a fiduciary duty to the company to exercise their powers bona fide in what they honestly consider to be the interests of the company. This duty is owed to the company and not generally to individual shareholders. In exercising the powers given to them by the constitution the directors have a fiduciary duty not only to act bona fide but also only to use their powers for a proper purpose. The powers are restricted to the purposes for which they were given.

Clearly the concepts of fiduciary duty and accountability are very similar though not identical. Where certain wider responsibilities are enshrined in law, do directors have a duty to go beyond the law, or can they regard the law as defining what society as a whole requires of them?

2.2.3 Fiduciary relationship with stakeholders 12/07

Evan and Freeman have argued that management bears a fiduciary relationship to stakeholders and to the corporation as an abstract entity. It must act in the interests of the stakeholders as their agent, and it must act in the interests of the corporation to ensure the survival of the firm, safeguarding the long-term stakes of each group. Adoption of these principles would require significant changes to the way corporations are run. Evan and Freeman propose a ‘stakeholder board of directors’, with one representative for each of the stakeholder groups and one for the company itself. Each stakeholder representative would be elected by a stakeholder assembly. Company law would have to develop to protect the interests of stakeholders.

Exam focus Question 4 in December 2007 asked students not only to explain what fiduciary responsibility was but also point to argue the case in favour of extending it. This illustrates that the examiner does not regard fiduciary duty as a legal concept set in stone, but one that can be used flexibly. A question in June 2013 asked for a description of fiduciary duty in the context of the case presented in the question.

2.2.4 Performance

The agent who agrees to act as agent for reward has a contractual obligation to perform their agreed task. An unpaid agent is not bound to carry out their agreed duties. Any agent may refuse to perform an illegal act.

2.2.5 Obedience

The agent must act strictly in accordance with their principal’s instructions provided that these are lawful and reasonable. Even if they believe disobedience to be in their principal’s best interests, they may not disobey instructions. Only if they are asked to commit an illegal act may they do so.

2.2.6 Skill

A paid agent undertakes to maintain the standard of skill and care to be expected of a person in their profession.

2.2.7 Personal performance

The agent is presumably selected because of their personal qualities and owes a duty to perform their task themselves and not to delegate it to another. But they may delegate in a few special circumstances, if delegation is necessary, such as a solicitor acting for a client would be obliged to instruct a stockbroker to buy or sell listed securities on a stock exchange.

2.2.8 No conflict of interest

The agent owes to their principal a duty not to put themselves in a situation where their own interests conflict with those of the principal. For example, they must not sell their own property to the principal (even if the sale is at a fair price).

2.2.9 Confidence

The agent must keep in confidence what they know of their principal’s affairs even after the agency relationship has ceased.

2.2.10 Any benefit

Any benefit must be handed over to the principal unless they agree that the agent may retain it. Although an agent is entitled to their agreed remuneration, they must account to the principal for any other benefits. If they accept from the other party any commission or reward as an inducement to make the contract with him, it is considered to be a bribe and the contract is fraudulent.

2.3 Agency in the context of the director-shareholder relationship 6/08

Agency is a significant issue in corporate governance because of the dominance of the joint-stock company, the company limited by shares as a form of business organisation. For larger companies this has led to the separation of ownership of the company from its management. The owners (the shareholders) can be seen as the principal, the management of the company as the agents.

Although ordinary shareholders (equity shareholders) are the owners of the company to whom the board of directors is accountable, the actual powers of shareholders tend to be restricted. They normally have no right to inspect the books of account, and their forecasts of future prospects are gleaned from the annual report and accounts, stockbrokers, journals and daily newspapers.

The day-to-day running of a company is the responsibility of the directors and other managers to whom the directors delegate, not the shareholders. For these reasons, therefore, there is the potential for conflicts of interest between management and shareholders.

| December 2013 Question 2 asked students to explain agency in the context of corporate governance. |

Exam focus point

2.4 The agency problem

The agency problem in joint stock companies derives from the principals (owners) not being able to run the business themselves and therefore having to rely on agents (directors) to do so for them. This separation of ownership from management can cause issues if there is a breach of trust by directors by intentional action, omission, neglect or incompetence. This breach may arise because the directors are pursuing their own interests rather than the shareholders’ or because they have different attitudes to risk taking to the shareholders.

For example, if managers hold none or very few of the equity shares of the company they work for, what is to stop them from working inefficiently, concentrating too much on achieving short-term profits and hence maximising their own bonuses, not bothering to look for profitable new investment opportunities, or giving themselves high salaries and perks?

One power that shareholders possess is the right to remove the directors from office. But shareholders have to take the initiative to do this and, in many companies, the shareholders lack the energy and organisation to take such a step. Ultimately they can vote in favour of a takeover or removal of individual directors or entire boards, but this may be undesirable for other reasons.

2.5 Agency costs

To alleviate the agency problem, shareholders have to take steps to exercise control, such as attending AGMs or ultimately becoming directors themselves. However, agency theory assumes that it will be expensive and difficult to:

- Verify what the agent is doing, partly because the agent has available more information about his activities than the principal does

- Introduce mechanisms to control the activities of the agent

The principals therefore incur agency costs, which are the costs of the monitoring that is required because of the separation of ownership and management. Common agency costs include:

- Costs of studying company data and results

- Purchase of expert analysis

- External auditors’ fees

- Costs of devising and enforcing directors’ contracts

- Time spent attending company meetings

- Costs of direct intervention in the company’s affairs

- Transaction costs of shareholding

To fulfil the requirements imposed on them (and to obtain the rewards of fulfilment) managers will spend time and resources proving that they are maximising shareholder value by, for example, providing increased disclosure or meeting with major shareholders.

Agency costs can be expensive for shareholders only holding shares in a few companies. For larger-scale investors, holding a portfolio containing the shares of many different companies, agency costs can be prohibitive. This illustrates the importance of minimising agency costs by aligning the interests of shareholders and directors.

Exam focus Your syllabus stresses the significance of agency problems in public listed companies. point

2.6 Resolving the agency problem: alignment of interests

Agency theory sees employees of businesses, including managers, as individuals, each with their own objectives. Within a department of a business, there are departmental objectives. If achieving these various objectives leads also to the achievement of the objectives of the organisation as a whole, there is said to be alignment of interests.

Key term Alignment of interests is accordance between the objectives of agents acting within an organisation and the objectives of the organisation as a whole. Alignment of interests is sometimes referred to as goal congruence, although goal congruence is used in other ways, as you will see in your P3 studies.

Alignment of interests may be better achieved and the ‘agency problem’ better dealt with by giving managers some profit-related pay, or by providing incentives that are related to profits or share price. Examples of such remuneration incentives are:

- Profit-related/economic value-added pay

Pay or bonuses related to the size of profits or economic value-added.

- Rewarding managers with shares

This might be done when a private company ‘goes public’ and managers are invited to subscribe for shares in the company at an attractive offer price. In a management buy-out or buy-in (the latter involving purchase of the business by new managers, the former by existing managers), managers become joint owner-managers.

- Executive share option plans (ESOPs)

In a share option scheme, selected employees are given a number of share options, each of which gives the holder the right after a certain date to subscribe for shares in the company at a fixed price. The value of an option will increase if the company is successful and its share price goes up, therefore giving managers an incentive to take decisions to increase the value of the company, actions congruent with wider shareholder interests.

Such measures might merely encourage management to adopt ‘creative accounting’ methods which will distort the reported performance of the company in the service of the managers’ own ends.

An alternative approach is to attempt to monitor managers’ behaviour; for example, by establishing ‘management audit’ procedures, to introduce additional reporting requirements, or to seek assurances from managers that shareholders’ interests will be foremost in their priorities. The most significant problem with monitoring is likely to be the agency costs involved, as they may imply significant shareholder engagement with the company.

2.7 Other agency relationships

2.7.1 Shareholder-auditor relationship

The shareholder-auditor relationship is another agency relationship on which corporate governance guidance has focused. The shareholders are the principals, the auditors are the agents and the audit report the key method of communication.

2.7.2 Shareholder-auditor relationship in public companies

An agency problem with auditors is that auditors may not be independent of the management of the companies that they audit. They become too close to management or are afraid that management will not give them non-audit work.

Corporate governance codes have sought to address this problem. However, the shareholder-auditor relationship in public companies imposes its own complexities. The auditors are acting as shareholders’ agents in monitoring the stewardship of directors. However, as we shall see in Chapter 8, the (nonexecutive) directors, who are on the audit committee, effectively also act as shareholders’ agents in monitoring the auditors. They are responsible for recommending the appointment and removal of the external auditors, fixing their remuneration, considering independence issues and discussing the scope of the audit.

The implication perhaps in most governance guidance is that the external auditors and non-executive directors are ‘on the same side’, with conflicts most likely to arise in tensions with executive directors (hence the possibility being raised in governance guidance of the external auditors and audit committee meeting without executive management being present). The situation breaks down if there is conflict between auditors and non-executive directors. Auditors then have the right to qualify their audit reports and make statements if they resign, but this is clearly a sign of problems that may require stakeholder intervention, time and cost.

2.7.3 Agency costs of external audit

Direct costs are obviously the audit fee. In addition, there will be the time spent by management and employees dealing with the information and preparing information for the auditors.

The amount of audit costs is not solely determined by the shareholders, but also influenced by the professional institutes to which the auditors belong and national and international government bodies. These institutions can influence audit fees directly, for example through rules on low-balling (fees that are too low). They can also impose requirements that indirectly add to the costs of audit. For example, institutes and standard-setting bodies lay down requirements that auditors must fulfil, impacting on the quality of work and the costs to be recovered. Governments, too, can take measures that will affect costs. For example, recent EU proposals (discussed further in Chapter 10) would require compulsory rotation of auditors every few years. This would most probably increase audit costs over time because new auditors would incur set-up costs when they started acting for a new client.

This in turn raises the issue of the extent to which influences other than shareholder opinions should determine audit work and audit costs. One argument might be that the audit fee is effectively a cost of risk management which reduces the earnings available to shareholders. If the shareholders are happy with the audit fee being low and hence the audit work carried out being limited, this implies that they are happy to accept increased risk in return for lower audit costs and higher earnings – it is fundamentally a risk-return decision. Well-informed potential investors and markets will take a similar view.

Critics of this view would argue that the impact of a company that has been inadequately audited falling into difficulties is potentially severe and goes well beyond the loss of shareholders’ investment. Employees, customers and suppliers can all be adversely affected and the wider economy may also be damaged if the company is large enough.

2.7.4 Other relationships

Other significant agency relationships include directors themselves acting as principals to managers/employees as agents. It is of course a significant responsibility of directors to make sure that this agency relationship works by establishing appropriate systems of performance measurement and monitoring (discussed in Chapter 8). In turn managers will act as principals to employees. There is also the relation between directors/managers and creditors, where creditors are seeking the payment of invoices on a timely basis.

Concerns over strategies and risks

A major concern in practice is likely to be if the shareholder is concerned about the strategies being adopted or the level of risks being taken, either too high or low. Arguably, if the shareholder is dissatisfied it can sell its shares and invest in companies whose strategies it trusts and whose risk appetites it shares. However in practice transaction costs plus the risk of not realising the full potential value from a sale may mean the shareholder is reluctant to sell.

Lack of communication by company

If the company does not, or is unwilling to, communicate proactively what shareholders wish to know, shareholders will need to find other means of obtaining information or make efforts to express their dissatisfaction. One thing acknowledged by the boards of companies that have been recently involved in controversy over executive pay (discussed further in Chapter 3) has been the need to communicate better with shareholders about directors’ remuneration.

Inadequacy of governance arrangements

The shareholder may need to spend more effort monitoring what the company is doing if it feels the corporate governance arrangements are inadequate. Particular concerns might be a very powerful chief executive and a lack of a strong non-executive director presence on the board.

Conflicts with other shareholders

The shareholder may have to incur costs and time if other, more powerful shareholders do not appear to share the shareholder’s concerns about the company in which they have invested. A common criticism in recent years is that institutional shareholders have given boards an easy ride, and failed to use the power their large shareholdings gives them to press the concerns of small shareholders without much influence.

2.8 Agency and public sector organisations

Public sector organisations also incorporate an agency relationship between the principals (the political leaders and ultimately the taxpayers/electors) and agents (the elected and executive officers and departmental managers). Because the taxpayers and electors have differing interests and objectives, establishing and monitoring the achievement of strategic objectives, and interpreting what is best for the principals, can be very difficult.

The agency problem in public services is also enhanced by limitations on the audit of public service organisations. In many jurisdictions the audit only covers the integrity and transparency of financial transactions and does not include an audit of performance or fitness for purpose.

2.9 Agency and charities

The agents in a charity are those responsible for spending donations and grants given. They include the directors and managers of the charitable services. Controls are needed to ensure that the interests of the principals (donors and recipients of charitable services) are maintained, and that funds are used for the intended purpose and not embezzled or used for self-enrichment.

Charities ensure that the agency problem is reduced and the goodwill of donors maintained by having a board of directors to run the charity, but also trustees to ensure that the board is delivering value to donors and to ensure that the charity’s aims are fulfilled. The trustees generally share the values of the charity and act like non-executive directors of public companies (discussed in Chapter 3). The trustees are likely to have the power to recruit and dismiss directors.

Agency problems in charities may not just arise from managers’ activities. An ambiguous relationship between the aims of the charity and commercial requirements may cause difficulty. Trustee prejudices may also hinder the relationship, particularly if they are trying to represent donors and beneficiaries who are largely silent. A lack of commercial knowledge and an unwillingness to change attitudes by the trustees may make the relationship problematic.

Publication of information about the contribution that the charity makes can help resolve the agency problem in charities. An annual report that clearly states how the charity is run and how it has delivered against its stated terms of reference and objectives can increase the confidence of donors, beneficiaries and regulators. A comprehensive audit of this information will reinforce its usefulness.

2.10 Transaction costs theory

Transactions cost theory is based on the work of Cyert and March and broadly states that the way the company is organised or governed determines its control over transactions. Companies will try to keep as many transactions as possible in-house in order to reduce uncertainties about dealing with suppliers, and about purchase prices and quality. To do this, companies will seek vertical integration (that is, they will purchase suppliers or producers later in the production process).

Transaction cost theory also states that managers are also opportunistic ie organise their transactions to pursue their own convenience. They will also be influenced by the amounts that they personally will gain, the probability of bad behaviour being discovered and the extent to which their actions are tolerated or even encouraged in corporate culture.

A further aspect of the theory is that managers will behave rationally up to a point, but this will be limited by the understanding of alternatives that they have.

The implications of transaction cost theory are that management may well play safe, and concentrate on easily understood markets and individual transactions they can easily control. This may mean that the company runs efficiently and, in its way, effectively. However, a focus on low-risk activities may discourage potential investors who are looking for a large return. Alternatively, shareholders dissatisfied with low profits may seek greater involvement in governance.

Internally senior managers will need to assess the impact of opportunistic issues, since this should determine the degree of monitoring that is needed over the activities of operational managers.

Thus despite differences of emphasis, transaction cost theory and agency theory are largely attempting to tackle the same problem, namely to ensure that managers effectively pursue shareholders’ best interests.

3 Types of stakeholders 12/07, 6/08, 12/08, 6/10

| Directors and managers need to be aware of the interests of stakeholders in governance; however, their responsibility towards them is judged. |

FAST FORWARD

3.1 Stakeholders

Key term Stakeholders are any entity (person, group or possibly non-human entity) that can affect or be affected by the achievements of an organisation’s objectives. It is a bi-directional relationship. Each stakeholder group has different expectations about what it wants and different claims on the organisation.

3.1.1 Stakeholder claims 12/12

The definition above highlights the important point for both business ethics and strategy, that stakeholders do not only just exist but also have claims on an organisation. Some stakeholders want to influence what the organisation does. Others are mainly concerned with how the organisation affects them and may want to increase or decrease this effect. However, there is the problem that some stakeholders do not know that they have a claim against the organisation, or know that they have a claim but do not know what it is.

A useful distinction is between direct and indirect stakeholder claims.

- Stakeholders who make direct claims do so with their own voice and generally do so clearly. Normally stakeholders with direct claims themselves communicate with the company.

- Stakeholders who have indirect claims are generally unable to make the claims themselves because they are for some reason inarticulate or voiceless. Although they cannot express their claim directly to the organisation, this does not necessarily invalidate their claim. Stakeholders may lack power because they have no significance for the organisation, have no physical voice (animals and plants), are remote from the organisation (suppliers based in other countries) or are future generations.

We shall discuss further the legitimacy of stakeholder claims and direct and indirect stakeholders later in this section.

Exam focus If you are asked to describe and assess a claim in the exam, remember that the fact that some point stakeholders have no voice does not invalidate their claims. Sometimes their claims may be the most powerful of all.

3.1.2 Importance of recognition of stakeholder claims 12/12

Knowledge of who stakeholders are and what claims they make is a vital part of an organisation’s risk assessment, since the claims made by the stakeholder can affect the achievement of objectives.

Stakeholders also have influences over the organisation. It is important to identify what these are and how significant they are, since it may determine the organisation’s decision if it has to decide between competing stakeholder claims. We discuss the assessment of the influence of stakeholders in terms of their power and interest below. An organisation also needs to know where likely areas of conflict and tension between stakeholders may arise.

3.1.3 Misinterpretation of stakeholder claims

As we shall see later in this chapter, assessment of stakeholder claims is potentially a difficult, subjective process. Organisations may also misinterpret the claims that stakeholders have or are making. This can mean that organisations take wrong or unnecessary actions, or fail to take the right actions, to deal with stakeholder concerns. It also may distort organisational priorities. There is possibly also an increased chance of conflict between the organisation and some stakeholders, as stakeholders who have strong grounds for feeling that their concerns are not being addressed properly take action.

Exam focus

point December 2012 Question 4 required students to identify and describe stakeholders and stakeholder claims in a scenario.

3.2 Stockholder theory (shareholder theory) 12/08

The theory that focuses on the interests of shareholders is known as stockholder theory, since it is mostly discussed in American literature.

Stockholder theory states that shareholders alone have a legitimate claim to influence over the company. It uses agency theory to argue that shareholders (as principals) own the company. Hence directors as agents have a moral and legal duty only to take account of shareholders’ interests. As it is assumed that shareholders wish to maximise their returns, then directors’ sole duty is to pursue profit maximisation.

This is the view of the pristine capitalist category defined by Gray, Owen and Adams that we shall consider further in Chapter 11.

3.3 Problems with stockholder view

Modern corporations have been seen as so powerful, socially, economically and politically, that unrestrained use of their power will inevitably damage other people’s rights. For example, they may blight an entire community by closing a major factory, inflicting long-term unemployment on a large proportion of the local workforce. They may use their purchasing power or market share to impose unequal contracts on suppliers and customers alike. They may exercise undesirable influence over government through their investment decisions. There is also the argument that corporations exist within society and are dependent on it for the resources they use. Some of these resources are obtained by direct contracts with suppliers but others are not, being provided by government expenditure.

Exam focus

point Remember in the exam that the stockholder view isn’t just an economic argument. Behind it is an ethical argument of fairly rewarding those who supply the company with its capital.

3.4 Stakeholder theory 12/08, 6/09

Stakeholder theory proposes corporate accountability to a broad range of stakeholders. It is based on companies being so large, and their impact on society being so significant, that they cannot just be responsible to their shareholders. There is a moral case for a business knowing how its decisions affect people both inside and outside the organisation. Stakeholders should also be seen not as just existing, but as making legitimate demands on an organisation. The relationship should be seen as a two-way relationship. There is much debate about which demands are legitimate, as we shall discuss below.

What stakeholders want from an organisation will vary. Some will actively seek to influence what the organisation does and others may be concerned with limiting the effects of the organisation’s activities on themselves.

Relations with stakeholders can also vary. Possible relationships can include conflict, support, regular dialogue or joint enterprise.

Exam focus

point If you’re asked to argue in favour of the stakeholder perspective in the exam, you’re likely to have to consider a number of different groups of stakeholders. December 2008 Question 1 required students to assess an ethical decision from the wider stakeholder perspective.

To what extent do you believe that animals should be considered as stakeholders? This is more than just a hypothetical question.

- Vegetarians do not eat meat because they believe that eating meat is wrong. Animals are ends in themselves, and do not exist just for our pleasure.

- Some anti-vivisection campaigners, such as The Body Shop, a cosmetics retailer, state they are against ‘animal testing’.

- Even if animals are to be eaten, some cultures require them to be treated well, according to humane standards, as animals are capable of suffering.

- The moral status of particular species of animals varies from culture to culture. Pigs are ‘unclean’ in Judaism and Islam. Beef is forbidden to Hindus. British people do not eat ‘horse’, although horses are eaten in other European countries. Similarly, eating dogs is perfectly acceptable in some cultures, but is totally unacceptable elsewhere. Guinea pigs are a food staple in the Andean countries, but are school pets in Britain. In some cultures, insects are eaten, in others, not.

- How would your views differ if you believed, as is the case in some religions, that animals contain the reincarnated souls of dead people?

- How would your view change if you believed that, like humans, some animal species are able to ‘learn’, exhibit altruistic behaviour, and that our sense of right and wrong results from evolutionary adaptation of the social behaviour patterns of our primate ancestors? (De Waal, 2001)

3.5 Instrumental and normative view of stakeholders

Donaldson and Preston suggested that there are two motivations for organisations responding to stakeholder concerns.

3.5.1 Instrumental view of stakeholders

This reflects the view that organisations have mainly economic responsibilities (plus the legal responsibilities that they have to fulfil in order to keep trading). In this viewpoint fulfilment of responsibilities towards stakeholders is desirable because it contributes to companies maximising their profits or fulfilling other objectives, such as gaining market share and meeting legal or stock exchange requirements. Therefore a business does not have any moral standpoint of its own. It merely reflects whatever the concerns are of the stakeholders it cannot afford to upset, such as customers looking for green companies or talented employees looking for pleasant working environments. The organisation is using shareholders instrumentally to pursue other objectives.

3.5.2 Normative view of stakeholders

This is based on the idea that organisations have moral duties towards stakeholders. Thus accommodating stakeholder concerns is an end in itself. This suggests the existence of ethical and philanthropic responsibilities as well as economic and legal responsibilities and organisations focusing on being altruistic.

The normative view is based on the ideas of the German philosopher Immanuel Kant. We shall discuss these in detail in Chapter 9. For now, Kant argued for the existence of civil duties that are important in maintaining and increasing the net good in society. Duties include the moral duty to take account of the concerns and opinions of others. Not to do so will result in breakdown of social cohesion leading to everyone being morally worse off, and possibly economically worse off as well.

| A question issued by the examiner required students to apply these two views of stakeholders to viewpoints expressed by directors. |

Exam focus point

3.6 Classifications of stakeholders

Stakeholders can be classified by their proximity to the organisation.

| Stakeholder group | Members |

| Internal stakeholders | Employees, management |

| Connected stakeholders | Shareholders, customers, suppliers, lenders, trade unions, competitors |

| External stakeholders | The Government, local government, the public, pressure groups, opinion leaders |

There are other ways of classifying stakeholders.

3.6.1 Legitimate and illegitimate stakeholders

| Stakeholder group | Members |

| Legitimate stakeholders | Those who have valid claims on the organisation |

| Illegitimate stakeholders | Those whose claims on the organisation are not valid |

This is possibly the most subjective distinction of all, depending as it does on views of which stakeholders should have a claim against the organisation. However, it is also the most important. A number of bases have been suggested for determining legitimacy.

- A contractual or exchange basis

- Different types of claim including legal, ownership or the firm being responsible for their welfare

- Stakeholders having something at risk as a result of investment in the firm or being affected by the firm’s activities

- Moral grounds; that the stakeholders benefit from or are harmed by the firm, or that their rights are being violated or not respected by the firm

Ultimately how the legitimacy of each stakeholder’s claim is viewed may well depend on the ethical and political perspective of the person judging it. The stockholder view for example would make the distinction solely on whether the stakeholder has an active economic relationship with the organisation. Stakeholders who might be difficult to categorise in this way include pressure groups and charities. However, others would argue for a wider definition, maybe including distant communities, other species, or future generations.

The problem of perception can result in conflict between stakeholders and the organisation. Stakeholder may claim legitimacy wrongly or management views of legitimacy may not be the same as stakeholders’ own perceptions.

3.6.2 Direct and indirect stakeholders

| Stakeholder group | Members |

| Direct stakeholders | Those who know they can affect or are affected by the organisation’s activities – employees, major customers and suppliers |

| Indirect stakeholders | Those who are unaware of the claims they have on the organisation or who cannot express their claim directly – wildlife, individual customers or suppliers of a large organisation, future generations |

This classification links to the discussion above about direct and indirect claims. It demonstrates a potential problem; that stakeholders who have the largest claim on an organisation may not be aware of its activities and its impact on them. A further issue is that indirect stakeholders’ claims have to be interpreted by someone else in order to be directly expressed. How can we tell what future generations would say? Do environmental pressure groups fairly interpret the needs of the natural environment?

3.6.3 Recognised and unrecognised stakeholders

| Stakeholder group | Members |

| Recognised stakeholders | Those whose interests and views managers consider when deciding on strategy |

| Unrecognised stakeholders | Those whose claims aren’t taken into account in the organisation’s decisionmaking – likely to be very much the same as illegitimate stakeholders |

3.6.4 Narrow and wide stakeholders 6/09

| Stakeholder group | Members |

| Narrow stakeholders | Those most affected by the organisation’s strategy – shareholders, managers, employees, suppliers, dependent customers |

| Wide stakeholders | Those less affected by the organisation’s strategy – government, less dependent customers, the wider community |

One implication of this classification might appear to be that organisations should pay most attention to narrow stakeholders, less to wider stakeholders.

| Question 1 in June 2009 asked students to identify three narrow stakeholders and assess the impact of the events described in the scenario on them. |

Exam focus point

3.6.5 Primary and secondary stakeholders

| Stakeholder group | Members |

| Primary stakeholders | Those without whose participation the organisation will have difficulty continuing as a going concern, such as shareholders, customers, suppliers and government (tax and legislation) |

| Secondary stakeholders | Those whose loss of participation won’t affect the company’s continued existence, such as broad communities (and perhaps management) |

Clearly an organisation must keep its primary stakeholders happy. The distinction between this classification and the narrow-wide classification is that the narrow-wide classification is based on how much the organisation affects the stakeholder. The primary-secondary classification is based on how much the stakeholders affect the organisation.

3.6.6 Active and passive stakeholders

| Stakeholder group | Members |

| Active stakeholders | Those who seek to participate in the organisation’s activities. Active stakeholders include managers, employees and institutional shareholders, but may also include other groups that are not part of the organisation’s structure, such as regulators or pressure groups |

| Passive stakeholders | Those who do not seek to participate in policy making, such as most shareholders, local communities and government |

Passive stakeholders may nevertheless still be interested and powerful. If corporate governance arrangements are to develop, there may be a need for powerful passive shareholders to take a more active role. Hence, as we shall see below, there has been emphasis on institutional shareholders who own a large part of listed companies’ shares actively using their power as major shareholders to promote better corporate governance.

3.6.7 Voluntary and involuntary stakeholders

| Stakeholder group | Members |

| Voluntary stakeholders | Those who engage with the organisation of their own free will and choice, and who can detach themselves from the relationship – management, employees, customers, suppliers, shareholders and pressure groups |

| Involuntary stakeholders | Those whose involvement with the organisation is imposed and who cannot themselves choose to withdraw from the relationship – regulators, government, local communities, neighbours, the natural world, future generations |

3.6.8 Known and unknown stakeholders

| Stakeholder group | Members |

| Known stakeholders | Those whose existence is known to the organisation |

| Unknown stakeholders | Those whose existence is unknown to the organisation (undiscovered species, communities in proximity to overseas suppliers) |

This distinction is important if you argue that an organisation should seek out all possible stakeholders before a decision is taken. The implication of this view is that the organisation should aim for its policies to have minimum impact.

| The examiner may ask you in your exam to identify the stakeholders mentioned in a case scenario, using stockholder and stakeholder perspectives. |

Exam focus point

3.7 Assessing the relative importance of stakeholder interests

Apart from the problem of taking different stakeholder interests into account, an organisation also faces the problem of weighing shareholder interests when considering future strategy. How, for example, do you compare the interest of a major shareholder with the interest of a local resident coping with the noise and smell from the company’s factory?

Power and interest

One way of weighing stakeholder interests is to look at the power they exert and the level of interest they have about its activities.

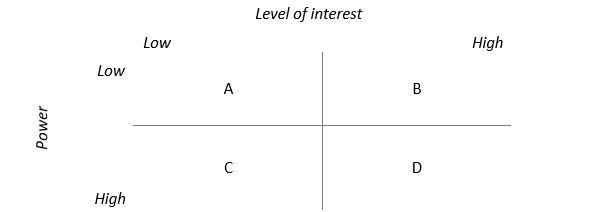

Mendelow classifies stakeholders on a matrix whose axes are power held and likelihood of showing an interest in the organisation’s activities. These factors will help define the type of relationship the organisation should seek with its stakeholders and how it should view their concerns. Mendelow’s matrix represents a continuum, a map for plotting the relative influence of stakeholders. Stakeholders in the bottom right of the continuum are more significant because they combine the highest power and influence.

- Key players are found in Segment D. The organisation’s strategy must be acceptable to them, at least. An example would be a major customer.

- Stakeholders in Segment C must be treated with care. They are capable of moving to Segment D.

They should therefore be kept satisfied. Large institutional shareholders might fall into Segment C.

- Stakeholders in Segment B do not have great ability to influence strategy, but their views can be important in influencing more powerful stakeholders, perhaps by lobbying. They should therefore be kept informed. Community representatives and charities might fall into Segment B.

- Minimal effort is expended on Segment A.

Stakeholder mapping is used to assess the significance of stakeholders. This in turn has implications for the organisation.

- The framework of corporate governance and the direction and control of the business should recognise stakeholders’ levels of interest and power.

- Companies may try to reposition certain stakeholders and discourage others from repositioning themselves, depending on their attitudes.

- Key blockers and facilitators of change must be identified.

- Stakeholder mapping can also be used to establish future priorities.

3.8.1 Using Mendelow’s approach to analyse stakeholders

Power means who can exercise most influence over a particular decision (though the power may not be used). These include those who actively participate in decision-making (normally directors, senior managers) or those whose views are regularly consulted on important decisions (major shareholders). It can also in a negative sense mean those who have the right of veto over major decisions (creditors with a charge on major business assets can prevent those assets being sold to raise money). Stakeholders may be more influential if their power is combined with:

Legitimacy: the company perceives the stakeholders’ claims to be valid

Urgency: whether the stakeholder claim requires immediate action

Level of interest reflects the effort stakeholders put in to attempting to participate in the organisation’s activities, whether they succeed or not. It also reflects the amount of knowledge stakeholders have about what the organisation is doing.

Goaway Hotels is a chain of hotels based in one country. Ninety per cent of its shares are held by members of the family of the founder of the Goaway group. None of the family members is a director of the company. Over the last few years, the family has been quite happy with the steady level of dividends that their investment has generated. Directors are encouraged to achieve high profits by means of a remuneration package with potentially very large profit-related bonuses.

The directors of Goaway Hotels currently wish to take significant steps to increase profits. The area they are focusing on at present is labour costs. Over the last couple of years, many of the workers they have recruited have been economic migrants from another country, the East Asian People’s Republic (EAPR). The EAPR workers are paid around 30% of the salary of indigenous workers, and receive fewer benefits. However, these employment terms are considerably better than those that the workers would receive in the EAPR. Goaway Hotels has been able to fill its vacancies easily from this source, and the workers from the EAPR that Goaway has recruited have mostly stayed with the company. The board has been considering imposing tougher employment contracts on home country workers, perhaps letting the number of dismissals and staff turnover of home country workers increase significantly.