SUPPLIER AND MARKET BEHAVIOUR

Market Structure

Meaning:

- Market structure refers to the nature and degree of competition in the market for goods and services. The structures of market both for goods market and service (factor) market are determined by the nature of competition prevailing in a particular market.

- The interconnected characteristics of a market, such as the number and relative strength of buyers and sellers and degree of collusion among them, level and forms of competition, extent of product differentiation, and ease of entry into and exit from the market

Determinants:

There are a number of determinants of market structure for a particular good.

They are:

(1) The number and nature of sellers.

(2) The number and nature of buyers.

(3) The nature of the product.

(4) The conditions of entry into and exit from the market.

(5) Economies of scale.

They are discussed as under:

1. Number and Nature of Sellers:

The market structures are influenced by the number and nature of sellers in the market. They range from large number of sellers in perfect competition to a single seller in pure monopoly, to two sellers in duopoly, to a few sellers in oligopoly, and to many sellers of differentiated products.

2. Number and Nature of Buyers:

The market structures are also influenced by the number and nature of buyers in the market. If there is a single buyer in the market, this is buyer’s monopoly and is called monopsony market. Such markets exist for local labour employed by one large employer. There may be two buyers who act jointly in the market. This is called duopsony market. They may also be a few organised buyers of a product.

This is known as oligopsony. Duopsony and oligopsony markets are usually found for cash crops such as rice, sugarcane, etc. when local factories purchase the entire crops for processing.

3. Nature of Product:

It is the nature of product that determines the market structure. If there is product differentiation, products are close substitutes and the market is characterised by monopolistic competition. On the other hand, in case of no product differentiation, the market is characterised by perfect competition. And if a product is completely different from other products, it has no close substitutes and there is pure monopoly in the market.

4. Entry and Exit Conditions:

The conditions for entry and exit of firms in a market depend upon profitability or loss in a particular market. Profits in a market will attract the entry of new firms and losses lead to the exit of weak firms from the market. In a perfect competition market, there is freedom of entry or exit of firms.

But in monopoly and oligopoly markets, there are barriers to entry of new firms. Usually, governments have a monopoly in public utility services like postal, air and road transport, water and power supply services, etc. By granting exclusive franchises, entries of new supplies are barred. In oligopoly markets, there are barriers to entry of firms because of collusion, tacit agreements, cartels, etc. On the other hand, there are no restrictions in entry and exit of firms in monopolistic competition due to product differentiation.

5. Economies of Scale:

Firms that achieve large economies of scale in production grow large in comparison to others in an industry. They tend to weed out the other firms with the result that a few firms are left to compete with each other. This leads to the emergency of oligopoly. If only one firm attains economies of scale to such a large extent that it is able to meet the entire market demand, there is monopoly.

Forms of Market Structure:

On the basis of competition, a market can be classified in the following ways:

- Perfect Competition

- Monopoly

- Duopoly

- Oligopoly

- Monopolistic Competition

Perfect Competition Market:

A perfectly competitive market is one in which the number of buyers and sellers is very large, all engaged in buying and selling a homogeneous product without any artificial restrictions and possessing perfect knowledge of market at a time. In the words of A. Koutsoyiannis, “Perfect competition is a market structure characterised by a complete absence of rivalry among the individual firms.” According to R.G. Lipsey, “Perfect competition is a market structure in which all firms in an industry are price- takers and in which there is freedom of entry into, and exit from, industry.”

Characteristics of Perfect Competition:

The following are the conditions for the existence of perfect competition:

(1) Large Number of Buyers and Sellers:

The first condition is that the number of buyers and sellers must be so large that none of them individually is in a position to influence the price and output of the industry as a whole. The demand of individual buyer relative to the total demand is so small that he cannot influence the price of the product by his individual action.

Similarly, the supply of an individual seller is so small a fraction of the total output that he cannot influence the price of the product by his action alone. In other words, the individual seller is unable to influence the price of the product by increasing or decreasing its supply.

Rather, he adjusts his supply to the price of the product. He is “output adjuster”. Thus no buyer or seller can alter the price by his individual action. He has to accept the price for the product as fixed for the whole industry. He is a “price taker”.

(2) Freedom of Entry or Exit of Firms:

The next condition is that the firms should be free to enter or leave the industry. It implies that whenever the industry is earning excess profits, attracted by these profits some new firms enter the industry. In case of loss being sustained by the industry, some firms leave it.

(3) Homogeneous Product:

Each firm produces and sells a homogeneous product so that no buyer has any preference for the product of any individual seller over others. This is only possible if units of the same product produced by different sellers are perfect substitutes. In other words, the cross elasticity of the products of sellers is infinite.

No seller has an independent price policy. Commodities like salt, wheat, cotton and coal are homogeneous in nature. He cannot raise the price of his product. If he does so, his customers would leave him and buy the product from other sellers at the ruling lower price.

The above two conditions between themselves make the average revenue curve of the individual seller or firm perfectly elastic, horizontal to the X-axis. It means that a firm can sell more or less at the ruling market price but cannot influence the price as the product is homogeneous and the number of sellers very large.

(4) Absence of Artificial Restrictions:

The next condition is that there is complete openness in buying and selling of goods. Sellers are free to sell their goods to any buyers and the buyers are free to buy from any sellers. In other words, there is no discrimination on the part of buyers or sellers.

Moreover, prices are liable to change freely in response to demand-supply conditions. There are no efforts on the part of the producers, the government and other agencies to control the supply, demand or price of the products. The movement of prices is unfettered.

(5) Profit Maximisation Goal:

Every firm has only one goal of maximising its profits.

(6) Perfect Mobility of Goods and Factors:

Another requirement of perfect competition is the perfect mobility of goods and factors between industries. Goods are free to move to those places where they can fetch the highest price. Factors can also move from a low-paid to a high-paid industry.

(7) Perfect Knowledge of Market Conditions:

This condition implies a close contact between buyers and sellers. Buyers and sellers possess complete knowledge about the prices at which goods are being bought and sold, and of the prices at which others are prepared to buy and sell. They have also perfect knowledge of the place where the transactions are being carried on. Such perfect knowledge of market conditions forces the sellers to sell their product at the prevailing market price and the buyers to buy at that price.

(8) Absence of Transport Costs:

Another condition is that there are no transport costs in carrying of product from one place to another. This condition is essential for the existence of perfect competition which requires that a commodity must have the same price everywhere at any time. If transport costs are added to the price of the product, even a homogeneous commodity will have different prices depending upon transport costs from the place of supply.

(9) Absence of Selling Costs:

Under perfect competition, the costs of advertising, sales-promotion, etc. do not arise because all firms produce a homogeneous product.

Perfect Competition vs Pure Competition:

Perfect competition is often distinguished from pure competition, but they differ only in degree. The first five conditions relate to pure competition while the remaining four conditions are also required for the existence of perfect competition. According to Chamberlin, pure competition means, competition unalloyed with monopoly elements,” whereas perfect competition involves perfection in many other respects than in the absence of monopoly.” The practical importance of perfect competition is not much in the present times for few markets are perfectly competitive except those for staple food products and raw materials. That is why, Chamberlin says that perfect competition is a rare phenomenon.”

Though the real world does not fulfil the conditions of perfect competition, yet perfect competition is studied for the simple reason that it helps us in understanding the working of an economy, where competitive behaviour leads to the best allocation of resources and the most efficient organisation of production. A hypothetical model of a perfectly competitive industry provides the basis for appraising the actual working of economic institutions and organisations in any economy.

2. Monopoly Market:

Monopoly is a market situation in which there is only one seller of a product with barriers to entry of others. The product has no close substitutes. The cross elasticity of demand with every other product is very low. This means that no other firms produce a similar product. According to D. Salvatore, “Monopoly is the form of market organisation in which there is a single firm selling a commodity for which there are no close substitutes.” Thus the monopoly firm is itself an industry and the monopolist faces the industry demand curve.

The demand curve for his product is, therefore, relatively stable and slopes downward to the right, given the tastes, and incomes of his customers. It means that more of the product can be sold at a lower price than at a higher price. He is a price-maker who can set the price to his maximum advantage.

However, it does not mean that he can set both price and output. He can do either of the two things. His price is determined by his demand curve, once he selects his output level. Or, once he sets the price for his product, his output is determined by what consumers will take at that price. In any situation, the ultimate aim of the monopolist is to have maximum profits.

Characteristics of Monopoly:

The main features of monopoly are as follows:

- Under monopoly, there is one producer or seller of a particular product and there is no difference between a firm and an industry. Under monopoly a firm itself is an industry.

- A monopoly may be individual proprietorship or partnership or joint stock company or a cooperative society or a government company.

- A monopolist has full control on the supply of a product. Hence, the elasticity of demand for a monopolist’s product is zero.

- There is no close substitute of a monopolist’s product in the market. Hence, under monopoly, the cross elasticity of demand for a monopoly product with some other good is very low.

- There are restrictions on the entry of other firms in the area of monopoly product.

- A monopolist can influence the price of a product. He is a price-maker, not a price-taker.

- Pure monopoly is not found in the real world.

- Monopolist cannot determine both the price and quantity of a product simultaneously.

- Monopolist’s demand curve slopes downwards to the right. That is why, a monopolist can increase his sales only by decreasing the price of his product and thereby maximise his profit. The marginal revenue curve of a monopolist is below the average revenue curve and it falls faster than the average revenue curve. This is because a monopolist has to cut down the price of his product to sell an additional unit.

3. Duopoly:

Duopoly is a special case of the theory of oligopoly in which there are only two sellers.

Characteristics

- Both the sellers are completely independent and

- no agreement exists between them.

- Even though they are independent, a change in the price and output of one will affect the other, and may set a chain of reactions.

- A seller may, however, assume that his rival is unaffected by what he does, in that case he takes only his own direct influence on the price.

If, on the other hand, each seller takes into account the effect of his policy on that of his rival and the reaction of the rival on himself again, then he considers both the direct and the indirect influences upon the price. Moreover, a rival seller’s policy may remain unaltered either to the amount offered for sale or to the price at which he offers his product. Thus the duopoly problem can be considered as either ignoring mutual dependence or recognising it.

4. Oligopoly:

Oligopoly is a market situation in which there are a few firms selling homogeneous or differentiated products. It is difficult to pinpoint the number of firms in ‘competition among the few.’ With only a few firms in the market, the action of one firm is likely to affect the others. An oligopoly industry produces either a homogeneous product or heterogeneous products.

The former is called pure or perfect oligopoly and the latter is called imperfect or differentiated oligopoly. Pure oligopoly is found primarily among producers of such industrial products as aluminium, cement, copper, steel, zinc, etc. Imperfect oligopoly is found among producers of such consumer goods as automobiles, cigarettes, soaps and detergents, TVs, rubber tyres, refrigerators, typewriters, etc.

Characteristics of Oligopoly:

In addition to fewness of sellers, most oligopolistic industries have several common characteristics which are explained below:

(1) Interdependence:

There is recognised interdependence among the sellers in the oligopolistic market. Each oligopolist firm knows that changes in its price, advertising, product characteristics, etc. may lead to counter-moves by rivals. When the sellers are a few, each produces a considerable fraction of the total output of the industry and can have a noticeable effect on market conditions.

He can reduce or increase the price for the whole oligopolist market by selling more quantity or less and affect the profits of the other sellers. It implies that each seller is aware of the price-moves of the other sellers and their impact on his profit and of the influence of his price-move on the actions of rivals.

Thus there is complete interdependence among the sellers with regard to their price-output policies. Each seller has direct and ascertainable influences upon every other seller in the industry. Thus, every move by one seller leads to counter-moves by the others.

(2) Advertisement:

The main reason for this mutual interdependence in decision making is that one producer’s fortunes are dependent on the policies and fortunes of the other producers in the industry. It is for this reason that oligopolist firms spend much on advertisement and customer services.

As pointed out by Prof. Baumol, “Under oligopoly advertising can become a life-and-death matter.” For example, if all oligopolists continue to spend a lot on advertising their products and one seller does not match up with them he will find his customers gradually going in for his rival’s product. If, on the other hand, one oligopolist advertises his product, others have to follow him to keep up their sales.

(3) Competition:

This leads to another feature of the oligopolistic market, the presence of competition. Since under oligopoly, there are a few sellers, a move by one seller immediately affects the rivals. So each seller is always on the alert and keeps a close watch over the moves of its rivals in order to have a counter-move. This is true competition.

(4) Barriers to Entry of Firms:

As there is keen competition in an oligopolistic industry, there are no barriers to entry into or exit from it. However, in the long run, there are some types of barriers to entry which tend to restraint new firms from entering the industry.

They may be:

(a) Economies of scale enjoyed by a few large firms; (b) control over essential and specialised inputs; (c) high capital requirements due to plant costs, advertising costs, etc. (d) exclusive patents and licenses; and (e) the existence of unused capacity which makes the industry unattractive. When entry is restricted or blocked by such natural and artificial barriers, the oligopolistic industry can earn long-run super normal profits.

(5) Lack of Uniformity:

Another feature of oligopoly market is the lack of uniformity in the size of firms. Finns differ considerably in size. Some may be small, others very large. Such a situation is asymmetrical. This is very common in the American economy. A symmetrical situation with firms of a uniform size is rare.

(6) Demand Curve:

It is not easy to trace the demand curve for the product of an oligopolist. Since under oligopoly the exact behaviour pattern of a producer cannot be ascertained with certainty, his demand curve cannot be drawn accurately, and with definiteness. How does an individual seller s demand curve look like in oligopoly is most uncertain because a seller’s price or output moves lead to unpredictable reactions on price-output policies of his rivals, which may have further repercussions on his price and output.

The chain of action reaction as a result of an initial change in price or output, is all a guess-work. Thus a complex system of crossed conjectures emerges as a result of the interdependence among the rival oligopolists which is the main cause of the indeterminateness of the demand curve.

If the oligopolist seller does not have a definite demand curve for his product, then how does he affect his sales. Presumably, his sales depend upon his current price and those of his rivals. However, a number of conjectural demand curves can be imagined.

For example, in differentiated oligopoly where each seller fixes a separate price for his product, a reduction in price by one seller may lead to an equivalent, more, less or no price reduction by rival sellers. In each case, a demand curve can be drawn by the seller within the range of competitive and monopoly demand curves.

Leaving aside retaliatory price movements, the individual seller’s demand curve under oligopoly for both price cuts and increases is neither more elastic than under perfect or monopolistic competition nor less elastic than under monopoly. It may still be indefinite and indeterminate.

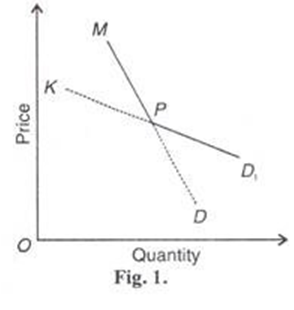

This situation is shown in Figure 1 where KD1 is the elastic demand curve and MD is the less elastic demand curve. The oligopolies’ demand curve is the dotted kinked KPD. The reason is quite simple. If a seller reduces the price of his product, his rivals also lower the prices of their products so that he is not able to increase his sales.

So the demand curve for the individual seller’s product will be less elastic just below the present price P (where KD1and MD curves are shown to intersect). On the other hand, when he raises the price of his product, the other sellers will not follow him in order to earn larger profits at the old price. So this individual seller will experience a sharp fall in the demand for his product.

Thus his demand curve above the price P in the segment KP will be highly elastic. Thus the imagined demand curve of an oligopolist has a comer or kink at the current price P. Such a demand curve is much more elastic for price increases than for price decreases.

(7) No Unique Pattern of Pricing Behaviour:

The rivalry arising from interdependence among the oligopolists leads to two conflicting motives. Each wants to remain independent and to get the maximum possible profit. Towards this end, they act and react on the price-output movements of one another in a continuous element of uncertainty.

On the other hand, again motivated by profit maximisation each seller wishes to cooperate with his rivals to reduce or eliminate the element of uncertainty. All rivals enter into a tacit or formal agreement with regard to price-output changes. It leads to a sort of monopoly within oligopoly.

They may even recognise one seller as a leader at whose initiative all the other sellers raise or lower the price. In this case, the individual seller’s demand curve is a part of the industry demand curve, having the elasticity of the latter. Given these conflicting attitudes, it is not possible to predict any unique pattern of pricing behaviour in oligopoly markets.

5. Monopolistic Competition:

Monopolistic competition refers to a market situation where there are many firms selling a differentiated product. “There is competition which is keen, though not perfect, among many firms making very similar products.” No firm can have any perceptible influence on the price-output policies of the other sellers nor can it be influenced much by their actions. Thus monopolistic competition refers to competition among a large number of sellers producing close but not perfect substitutes for each other.

It’s Features:

The following are the main features of monopolistic competition:

(1) Large Number of Sellers:

In monopolistic competition the number of sellers is large. They are “many and small enough” but none controls a major portion of the total output. No seller by changing its price-output policy can have any perceptible effect on the sales of others and in turn be influenced by them. Thus there is no recognised interdependence of the price-output policies of the sellers and each seller pursues an independent course of action.

(2) Product Differentiation:

One of the most important features of the monopolistic competition is differentiation. Product differentiation implies that products are different in some ways from each other. They are heterogeneous rather than homogeneous so that each firm has an absolute monopoly in the production and sale of a differentiated product. There is, however, slight difference between one product and other in the same category.

P roducts are close substitutes with a high cross-elasticity and not perfect substitutes. Product “differentiation may be based upon certain characteristics of the products itself, such as exclusive patented features; trade-marks; trade names; peculiarities of package or container, if any; or singularity in quality, design, colour, or style. It may also exist with respect to the conditions surrounding its sales.”

(3) Freedom of Entry and Exit of Firms:

Another feature of monopolistic competition is the freedom of entry and exit of firms. As firms are of small size and are capable of producing close substitutes, they can leave or enter the industry or group in the long run.

(4) Nature of Demand Curve:

Under monopolistic competition no single firm controls more than a small portion of the total output of a product. No doubt there is an element of differentiation nevertheless the products are close substitutes. As a result, a reduction in its price will increase the sales of the firm but it will have little effect on the price-output conditions of other firms, each will lose only a few of its customers.

Likewise, an increase in its price will reduce its demand substantially but each of its rivals will attract only a few of its customers. Therefore, the demand curve (average revenue curve) of a firm under monopolistic competition slopes downward to the right. It is elastic but not perfectly elastic within a relevant range of prices of which he can sell any amount.

(5) Independent Behaviour:

In monopolistic competition, every firm has independent policy. Since the number of sellers is large, none controls a major portion of the total output. No seller by changing its price-output policy can have any perceptible effect on the sales of others and in turn be influenced by them.

(6) Product Groups:

There is no any ‘industry’ under monopolistic competition but a ‘group’ of firms producing similar products. Each firm produces a distinct product and is itself an industry. Chamberlin lumps together firms producing very closely related products and calls them product groups, such as cars, cigarettes, etc.

(7) Selling Costs:

Under monopolistic competition where the product is differentiated, selling costs are essential to push up the sales. Besides, advertisement, it includes expenses on salesman, allowances to sellers for window displays, free service, free sampling, premium coupons and gifts, etc.

(8) Non-price Competition:

Under monopolistic competition, a firm increases sales and profits of his product without a cut in the price. The monopolistic competitor can change his product either by varying its quality, packing, etc. or by changing promotional programmes.

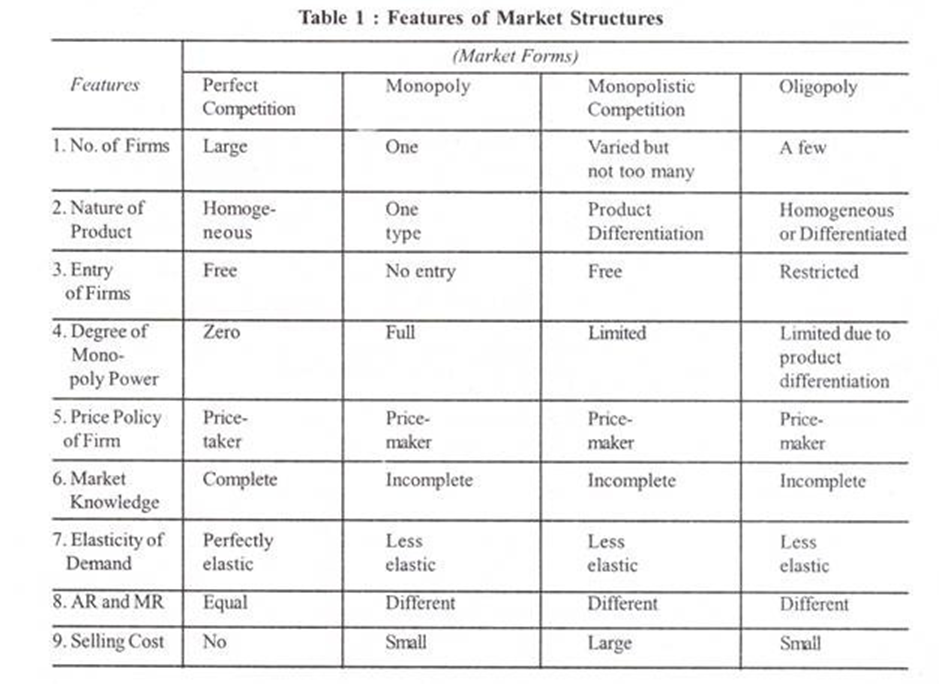

The features of market structures are shown in Table 1.

Advertisements:

- Pricing strategies

- Fixed price

The term fixed price is a phrase used to mean the price of a good or a service is not subject to bargaining. The term commonly indicates that an external agent, such as a merchant or the government, has set a price level, which may not be changed for individual sales. In the case of governments, this may be due to price controls.

Bargaining is very common in many parts of the world, outside of retail stores in Europe or North America or Japan, this makes this an exception from the general norm of pricing in these areas.

Mitsui Takatoshi that it was begun by the world and a fixed price was used.

A fixed-price contract is a contract where the contract payment does not depend on the amount of resources or time expended by the contractor, as opposed to cost-plus contracts. These contracts are often used in military and government contractors to put the risk on the side of the vendor, and control costs.

Historically, when fixed-price contracts are used for new projects with untested or developmental technologies, the programs may fail if unforeseen costs exceed the ability of the contractor to absorb the overruns. In spite of this, such contracts continue to be popular. Fixed-price contracts tend to work when costs are well known in advance

- Cost Price

This is your own calculation of how much it cost you to actually produce your products. It includes your time x hourly rate, material and marketing costs, but also overheads such as studio rent, telephone and transport. Costing your product or service correctly is the foundation of how you will price your work.

You need to keep your cost price confidential, and do not share with others such as your retailers or competitors.

3. Target pricing business

Pricing method whereby the selling price of a product is calculated to produce a particular rate of return on investment for a specific volume of production. The target pricing method is used most often by public utilities, like electric and gas companies, and companies whose capital investment is high, like automobile manufacturers.

Target pricing is not useful for companies whose capital investment is low because, according to this formula, the selling price will be understated. Also the target pricing method is not keyed to the demand for the product, and if the entire volume is not sold, a company might sustain an overall budgetary loss on the product.

4. Psychological pricing

Pricing designed to have a positive psychological impact. For example, selling a product at $3.95 or $3.99, rather than $4.00. There are certain price points where people are willing to buy a product. If the price of a product is $100 and the company prices it as $99, then it is called psychological pricing. In most of the consumers mind $99 is psychologically ‘less’ than $100. A minor distinction in pricing can make a big difference in sales. The company that succeeds in finding psychological price points can improve sales and maximize revenue.

5. Contribution margin-based pricing

Contribution margin-based pricing maximizes the profit derived from an individual product, based on the difference between the product’s price and variable costs (the product’s contribution margin per unit), and on one’s assumptions regarding the relationship between the product’s price and the number of units that can be sold at that price. The product’s contribution to total firm profit (i.e. to operating income) is maximized when a price is chosen that maximizes the following: (contribution margin per unit) X (number of units sold).

In cost-plus pricing, a company first determines its break-even price for the product. This is done by calculating all the costs involved in the production, marketing and distribution of the product. Then a markup is set for each unit, based on the profit the company needs to make, its sales objectives and the price it believes customers will pay. For example, if the company needs a 15 percent profit margin and the break-even price is $2.59, the price will be set at $2.98 ($2.59 x 1.15).[2]

6. Decoy pricing

Method of pricing where the seller offers at least three products, and where two of them have a similar or equal price. The two products with the similar prices should be the most expensive ones, and one of the two should be less attractive than the other. This strategy will make people compare the options with similar prices, and as a result sales of the most attractive choice will increase.

7. High-low pricing

Method of pricing for an organization where the goods or services offered by the organization are regularly priced higher than competitors, but through promotions, advertisements, and or coupons, lower prices are offered on key items. The lower promotional prices are designed to bring customers to the organization where the customer is offered the promotional product as well as the regular higher priced products.[4]

8. Limit pricing

A limit price is the price set by a monopolist to discourage economic entry into a market, and is illegal in many countries. The limit price is the price that the entrant would face upon entering as long as the incumbent firm did not decrease output. The limit price is often lower than the average cost of production or just low enough to make entering not profitable. The quantity produced by the incumbent firm to act as a deterrent to entry is usually larger than would be optimal for a monopolist, but might still produce higher economic profits than would be earned under perfect competition.

The problem with limit pricing as a strategy is that once the entrant has entered the market, the quantity used as a threat to deter entry is no longer the incumbent firm’s best response. This means that for limit pricing to be an effective deterrent to entry, the threat must in some way be made credible. A way to achieve this is for the incumbent firm to constrain itself to produce a certain quantity whether entry occurs or not. An example of this would be if the firm signed a union contract to employ a certain (high) level of labor for a long period of time. In this strategy price of the product becomes the limit according to budget.

9. Loss leader

A loss leader or leader is a product sold at a low price (i.e. at cost or below cost) to stimulate other profitable sales. This would help the companies to expand its market share as a whole.

10.Marginal-cost pricing

In business, the practice of setting the price of a product to equal the extra cost of producing an extra unit of output. By this policy, a producer charges, for each product unit sold, only the addition to total cost resulting from materials and direct labor. Businesses often set prices close to marginal cost during periods of poor sales. If, for example, an item has a marginal cost of $1.00 and a normal selling price is $2.00, the firm selling the item might wish to lower the price to $1.10 if demand has waned. The business would choose this approach because the incremental profit of 10 cents from the transaction is better than no sale at all.

11.Market-oriented pricing

Setting a price based upon analysis and research compiled from the target market. This means that marketers will set prices depending on the results from the research. For instance if the competitors are pricing their products at a lower price, then it’s up to them to either price their goods at an above price or below, depending on what the company wants to achieve.

12.Odd pricing

In this type of pricing, the seller tends to fix a price whose last digits are odd numbers. This is done so as to give the buyers/consumers no gap for bargaining as the prices seem to be less and yet in an actual sense are too high, and takes advantage of human psychology. A good example of this can be noticed in most supermarkets where instead of pricing at $10, it would be written as $9.99.

13.Pay what you want/ONO

Pay what you want is a pricing system where buyers pay any desired amount for a given commodity, sometimes including zero. In some cases, a minimum (floor) price may be set, and/or a suggested price may be indicated as guidance for the buyer. The buyer can also select an amount higher than the standard price for the commodity.

Giving buyers the freedom to pay what they want may seem to not make much sense for a seller, but in some situations it can be very successful. While most uses of pay what you want have been at the margins of the economy, or for special promotions, there are emerging efforts to expand its utility to broader and more regular use.

14.Penetration pricing

Penetration pricing includes setting the price low with the goals of attracting customers and gaining market share. The price will be raised later once this market share is gained.[5]

15.Predatory pricing

Main article: Predatory pricing

Predatory pricing, also known as aggressive pricing (also known as “undercutting”), intended to drive out competitors from a market. It is illegal in some countries.

16.Premium decoy pricing

Method of pricing where an organization artificially sets one product price high, in order to boost sales of a lower priced product.

17.Premium pricing

Main article: Premium pricing

Premium pricing is the practice of keeping the price of a product or service artificially high in order to encourage favorable perceptions among buyers, based solely on the price. The practice is intended to exploit the (not necessarily justifiable) tendency for buyers to assume that expensive items enjoy an exceptional reputation, are more reliable or desirable, or represent exceptional quality and distinction.

18. Price discrimination

Main article: Price discrimination

Price discrimination is the practice of setting a different price for the same product in different segments to the market. For example, this can be for different classes, such as ages, or for different opening times.

19.Price leadership

An observation made of oligopolistic business behavior in which one company, usually the dominant competitor among several, leads the way in determining prices, the others soon following. The context is a state of limited competition, in which a market is shared by a small number of producers or sellers.