NATURE AND CLASSIFICATION OF LAW

The term “law” has no assigned meaning. It is used in a variety of senses. The study of law is referred to as jurisprudence or legal philosophy.

According to Hart Law is a coercive instrument for regulating social behaviour. Law has also been defined as a command backed by sanctions.

According to Salmond, law consists of a body of principles recognised and applied by the state in the administration of justice.

Law has also been defined as a collection of binding rules of human conduct prescribed by human beings for obedience of human beings.

Therefore law implies rules or principles enforced by courts of law. Rules of law are binding hence differ from other rules or regulations. Rules of law are certain.

In summary therefore, law is an aggregate of conglomeration of rules enforced by courts of law at a given time.

Rules of law originate from acts of parliament, customary and religious practises of the people, they may also be borrowed from other countries.

Law and Morality

Morality consists of prescriptions of the society and is not enforceable, however, rules of law are enforceable. Wrongs in society are contraventions of either law or morality or both.

However, law incorporates a significant proportion of morality and to that extent morality is enforceable.

However, such rules/contraventions are contraventions of law for example murder, rape theft by servant or agent.

Purposes or Functions of Law

(i) Rules of law facilitate administration of justice. It is an instrument used by human beings to achieve justice.

(ii) Law assists in the maintenance of peace and order. Law promotes peaceful co-existence, that is, prevents anarchy.

(iii) Law promotes good governance.

(iv) Law is a standard setting and control mechanism.

(v) Provision of legal remedies, protection of rights and duties.

Types and Classification of Law

- Written Law

These are rules of law that have been reduced into a written form. They are embodied in a formal document for example The Constitution of Kenya, laws made by parliament (statutes). Such laws prevail over unwritten Law.

- Unwritten Law

These are rules of law that have not been reduced into written form. They are not embodied in any single document for example African Customary Law, Islamic Law, Hindu Law, Common Law, Equity. Their existence must be proved.

- National or Municipal Law

These are rules of law operational within the boundaries of a country. It regulates the relation between citizens and the state. It is based on Acts of Parliament, customary and religious practices of the people.

- International Law

It is a body of rules that regulates relations between countries/states and other international persons eg United Nations. It is based on international agreements or treaties and customary practices of states

- Public Law

It consists of those fields or branches of law in which the state has an interest as the sovereign eg criminal law, constitutional law, and administrative law.

Public law is concerned with the constitution and functions of the various organs of government including local authorities, their relations with each other and with the citizens.

- Private law

It consists of those fields or branches of law in which the state has no direct interest as the sovereign egg law of contracts, law of tort, law of property, law of succession.

Private law is concerned with day to day transactions of legal relationships between persons. It defines the rights and duties of parties.

- Substantive Law

It is concerned with the rules themselves as opposed to the procedure on how to apply them. It defines the rights and duties of parties and provides remedies when those rights are violated e.g. law of contract, negligence, and defamation. It defines offences and prescribes punishment e.g. Penal Code Cap 63.

- Procedural Law

It consists of the steps or guiding principles or rules of practice to be complied with or followed in the administration of justice or in the application of substantive law.

It is also referred to as adjective law e.g. Criminal Procedure code Cap 75, civil procedure Act Cap 21.

- Criminal Law

Criminal law has been defined as the law of crimes. A crime has been defined as an act or omission, committed or omitted in violation of public law eg murder, manslaughter, robbery, burglary, rape, stealing, theft by servant or agent.

All crimes or offences in Kenya are created by parliament through statutes. Suspects are arrested by the state through the police. However, individuals have the liberty to arrest suspects. Offences are generally prosecuted by the state through the office of the Attorney General.

Under section 77 (2) (a) of the constitution an accused person is presumed innocent until proven or has pleaded guilty. It is the duty of the prosecution to prove its case against the accused. The burden of proof rests on the prosecution.

The standard of proof in criminal cases is beyond any reasonable doubt. In the event of any reasonable doubt the accused is set free (acquitted). The court must be satisfied that the accused committed offence as charged. If the prosecution discharges the burden of proof the accused is convicted and sentenced which could take any of the following forms.

- Imprisonment term

- Capital punishment

- Corporal punishment

- Community service

- Fine

- Conditional discharge

- Unconditional discharge

The purpose of criminal law is;

- To ascertain whether or not the crime has been committed.

- To punish the crime where one has been comm-itted.

10.Civil Law

Civil law is concerned with violations of private rights in their individual or corporate capacity eg breach of contract, negligence, and defamation, nuisance, passing off trespass to the person or goods.

If a person’s private rights are violated, the person has a cause of action. Causes of action are recognized by statutes and by the common law. The person whose rights have been allegedly violated sues the alleged wrong doer. It is his duty of the plaintiff to adduce evidence to prove his case the burden of proof lies on the plaintiff.

If the plaintiff discharges the burden of proof then he wins the case and is awarded judgement which could take any of the following forms:

- Damage, i.e. monetary compensation

- Injunction

- Winding up/liquidation

Purpose of civil laws

(i) Protection of rights and enforcement of duties.

(ii) Provision of legal remedies as and when a person’s rights have been violate

SOURCES OF KENYA LAW

A source of law is the origin of the rule, which constitutes a law, or legal principle. The phrase `sources of Kenya law’ therefore means the origin of the legal rules which constitute the law of Kenya.

The sources of Kenya law are specified in the Judicature Act 1967, S.3(1) of which states that the jurisdiction of the High Court, the Court of Appeal and all subordinate courts shall be exercised in accordance with:

The constitution;

“All other written laws”, (including certain Acts of Parliament

The Kadhi’s Courts Act 1967

Section 5 of the Kadhi’s Courts Act provides that a Kadhi’s Court shall have and exercise jurisdiction in matters involving the determination of Muslim Law relating to personal status, marriage, divorce or inheritance in proceedings in which all the parties profess the Muslim religion.

The Hindu Marriage and Divorce Act 1960, S.5 (1)

Provides that a marriage between Hindus may be solemnized in accordance with the customary rites and ceremonies of either party thereto.

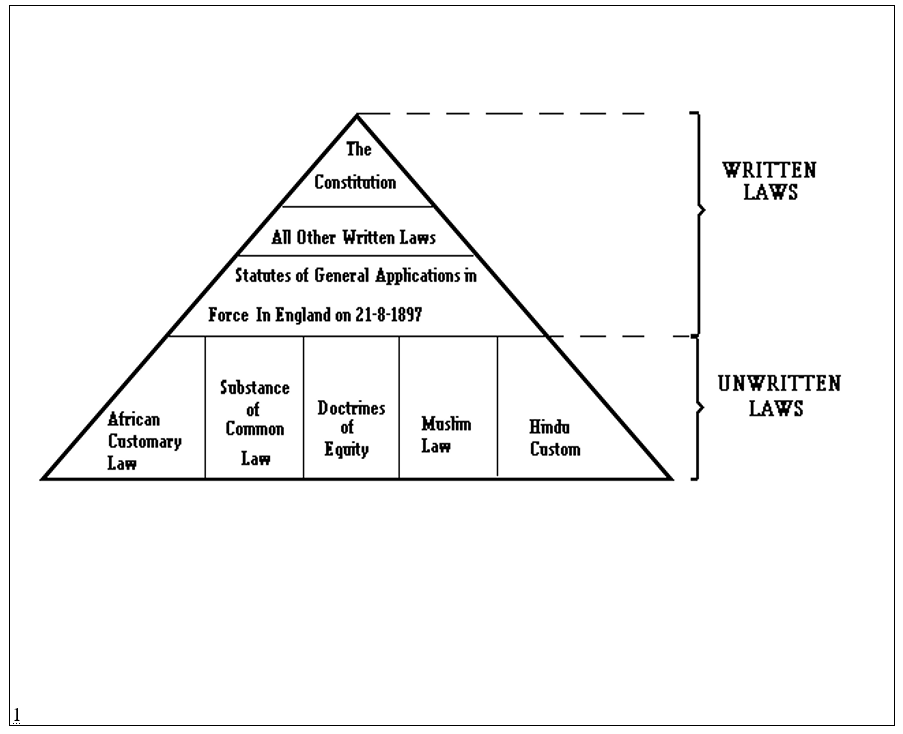

The Legal Pyramid

The sources of Kenya law mentioned above may be summarised with the aid of the following diagram or “legal pyramid”:

STATUTE LAW

This is an Act of Parliament. This is law made by parliament directly in exercise of legislative power conferred upon it by the constitution.

Section 46(5) of the Kenya Constitution states that “a law made by Parliament shall be styled an Act of Parliament”.

Bills

An Act of Parliament begins as a Bill, which is the draft of law that Parliament intends to make. Section 46(1) of the constitution states that “the legislative power of Parliament shall be exercisable by Bills passed by the National Assembly”.

Types of Bills

A Government Bill, if it is presented to Parliament by the Government with a view to its becoming a law if approved by Parliament.

A Private Members’ Bill if it is presented to Parliament by some members, in a private capacity and not on behalf of the Government.

Bills may also be divided into Public Bills and Private Bills.

A Bill, whether a Government Bill or a Private Members’ Bill, is a Public Bill if it seeks to alter the law throughout Kenya. An example is the abortive Marriage Bill, 1979, whose aim was to introduce a uniform marriage law for all Kenyans irrespective of their racial, religious or ethnic differences.

A Private Bill if it does not seek to alter the general law but rather to confer special local powers. An example is where a local authority such as a Municipal Council requires power to purchase land compulsorily.

PROCEDURE FOR ENACTMENT OF LAWS

The procedure to be followed in Parliament in order to enact Law is governed by Constitution and Orders 94-125 of National Assembly Standing Orders, as amended up to and including 22nd July, 1983.

A Government Bill and a Private Members’ Bill follow the same procedure pursuant to Order 116 which provides that, except as otherwise provided in Part XVI of the Orders, the Standing Orders relating to Public Bills shall apply in respect of Private Bills.

Publication of Bills in the Kenya Gazette

Order 98 provides that no Bill shall be introduced unless it has been published in the Gazette and a period of fourteen days beginning with the day of such publication, or such shorter period as the House may resolve with respect to the Bill.

the period of publication for a Consolidated Fund Bill, an Appropriation Bill or a Supplementary Appropriation Bill is seven days only.

1. First Reading

Order 101 provides that “every Bill shall be read a First Time without motion made or question put and shall be ordered to be read a second time on such day as the member in charge of it shall appoint”. No debate takes place it is therefore a mere formality.

- Second Reading

During the second reading the general merits of the Bill may be debated and any necessary amendments are proposed to the various clauses it contains. Every member wishing to contribute is offered the opportunity.

- Committal Stage

Order 103 provides that a Bill having been read a second time shall stand committed to a committee of the Whole House, unless the House commits the Bill to a select committee of members of parliament for a critical analysis.

Order 104 provides that all committees to which Bills are committed shall have power to make such amendments thereto as they think fit, and shall report the amendment to the House.

- Report Stage

Order 106(12) provides that at the conclusion of the proceedings in committee on a Bill a Minister, or the member in charge, shall move “That the Bill (as amended) be reported to the House”, and the question thereon shall be decided without amendment or debate. The chairman of the select committee lenders its report to the National Assembly.

- Third Reading

It is provided in Order 112(1) that on the adoption of a report on a Bill the Third Reading may with leave of Mr. Speaker be taken forthwith and if not so taken forthwith shall be ordered to be taken on a day named by the member in charge of the Bill.

Order 112(2) provides that on the third reading of a Bill amendments may be proposed similar to those proposed on second reading.

- THE PRESIDENT’S ASSENT

Under section 46(2) of the Constitution a Bill passed by the National Assembly must be presented to the

President for his assent.

|The President must signify his assent or refusal to the speaker of the National Assembly within 21 days

of receipt of the Bill.

If he refuses to assent, he must within l4 days thereof deliver to speaker a written memorandum of the

provisions he would like reconsidered and his recommendations and the National Assembly may either:

Re-pass the Bill incorporating the Presidents recommendation with or without amendments and resent it for his assent or

Re-pass the Bill in its original form thus ignoring the President’s recommendations. If the resolution

to re-pass the Bill is such is supported by at least 65% of all members excluding ex-officio members the President must signify his assent within 14 days of the resolution.

- PUBLICATION

Section 46(3) of the constitution states that `upon a Bill that has been passed by the National Assembly being presented to the President for assent, it shall become law and shall thereupon be published in the Kenya Gazette as a law’. The wording of this section does not appear to prescribe the President’s assent as a condition precedent to the enactment of a Bill, although in practice the assent is so regarded.

- COMMENCEMENT

Section 46(4) of the constitution provides that a law made by Parliament shall not come into operation until it has been published in the Kenya Gazette. But it also empowers Parliament, subject to certain exceptions, to postpone the coming into operation of any law and to make laws with retrospective effect.

ADVANTAGES OF ACTS OF PARLIAMENT

- i) Democratic in nature

It is democratic in the sense that it reflects the wishes of Kenyans as to what the law should be. This is because it is made by a Parliament which consists of representatives of the people who are elected at intervals of not more than five years.

(ii)Resolution of Legal Problems

It enables Parliament to find legal solutions to any problem that the country may face. An English judge once stated that an Act of Parliament can in theory deal with any problem except that it cannot change man to woman, (although it may provide that reference therein to `man’ shall include ‘woman’.)

(iii) Dynamic: It enables new challenges that emerge in the course of social development to be legally dealt

with by the passing of new Acts of Parliament, or amending some of the existing Acts.

(iv) General Application: It is usually a statement of general principles and rules and can therefore be applied to

different situations in a flexible manner as determined by the court in a particular situation

(v) Uniformly Applied. It applies indiscriminately.

(vi) Publicity: Statute law is the most widely published source of law.

DISADVANTAGES OF STATUTE LAW

(i) Imposition of law

Some Acts are imposed on the people and reflect the views of the Executive, or pundits in the ruling political

party.

Parliament now governs only in the technical formal sense”, and largely rubber-stamps what is put before it

by the Executive.

(ii) Wishes of members of parliament

Acts of Parliament do not reflect the wishes of the people (voters) but the wishes of the individuals who constitute Parliament at any given time. During debates on Bills, Members of Parliament express their personal views and finally enact laws on the basis of those views. They do not hold meetings in their constituencies to ascertain what the people’s views on Bills are so that they may eventually report back to Parliament

(iii) Bulky and technical Bills

Some Bills are so bulky and technical that they are passed without sufficient debate because Parliament lacks the time and knowledge to consider them in detail. E.g Finance Bills.

(iv) Formalities

The process of enacting a statute that would substantially conform to the wishes of the people affected by it would be very slow. This is because very many public meetings must be held before a consensus on the proposed law can be reached. The delay in re-introducing the abortive Marriage Bill, 1979 illustrates this point.

STATUTORY INTERPRETATION

The precise meaning of a law written in an Act may cause a legal dispute. This is so because, although the law is written and can therefore be read by any literate person, some of the words thereof may not mean the same thing to different readers. This fact has been confirmed by the arguments adduced in court by parties to such disputes.

Principles and Presumptions of Construction

In the course of settling some of these disputes the courts in England have elaborated the rules which they will use in order to interpret, if necessary, any Act. Assuming that the same rules have been or will be adopted by Kenya courts, they may be summarised as follows:

(i) Literal rule

The primary rule of interpretation is known as the literal rule. It requires judges to interpret the words of a statute according to their grammatical or literal meaning.

Generally speaking, every word in an Act must be given a meaning and no word is to be added to, or taken from, the Act.

(ii) ‘Mischief’ rule (Rule in Heydons Case)

Under this rule the court will examine the Act to ascertain what its purpose was and the ‘mischief’, or defect, in the common law that it was intended to remove. This rule was explained in HEYDON’S CASE as follows:

“Four things are to be discussed and considered:

(i) what was the common law before the making of the Act?

(ii) what was the mischief and defect for which the common law did not provide?

(iii) what remedy has Parliament resolved and appointed to cure the disease?

(iv) what is the true reason for the remedy? Judges shall…. make such construction as shall suppress the mischief and advance the remedy”.

A statute will only be construed in accordance with this rule if its construction in accordance with the literal rule would fail to suppress, or punish, the mischief. An example of this can be seen in the case of SMITH v HUGHES where it was held that a prostitute who attracted the attention of passers by from a balcony window above the street had solicited in a street within Section 1(1) of the English Street Offences Act, 1959. The judge stated as follows:

“I approach the matter by considering what is the mischief aimed at by this Act. Everybody knows that this was an Act intended to clean up the streets, to enable people to walk along the streets without being molested or solicited by common prostitutes”.

Viewed in that way, the actual place from which a prostitute attracted the attention of somebody walking in the street did not matter, and she will be deemed to have solicited in the street

(iii) The ‘Golden’ rule

The so-called ‘golden’ rule will be used by the court in order to avoid arriving at an absurd decision under the literal rule of construction. It was explained by Parker B in case of BECKE v SMITH as follows:

“It is a very useful rule, in the construction of a statute, to adhere to the ordinary meaning of words used, and to the grammatical construction, unless that is at variance with the intention of the legislature, to be collected from the statute itself, or leads to any manifest absurdity or repugnance, in which case the language may be varied or modified.”.

An example of the application of the rule is INDEPENDENT AUTOMATIC SALES LTD v KNOWLES & FOSTER where it was held that a debt may be regarded as a “book debt” within s.95 (2)(e) of the English Companies Act 1948 even though it has not been entered in the books of the business, provided that it would or could in the ordinary course of such business be entered in well-kept books relating to that business. To restrict the phrase “book debts” to those debts entered in the books of the business would have entailed an unrealistic and illogical categorization of the debts of the business.

(iv)The ‘ejusdem generis’ rule

This rule states that where general words in an Act follow particular words, the general words are to be construed as being limited to the persons or things within the class designated by the particular words. For example, in a reference to “cows, goats, donkeys and other animals” the general words “other animals” would be construed to mean animals of the same genus or species as cows, goats and donkeys, that is, domestic animals, and would not include wild animals such as zebras, antelopes or tigers.

Expressio unius est etclusio ullerius

Nositier a Soiis

Rendedo Singular Singular

A statute must be constued as a whole

Rank Principle

Statutes in Pari maleria

In EVANS v CROSS, Evans was charged with ignoring a traffic sign, namely, a white line painted in the middle of a road, when overtaking on a bend into the road, contrary to Section 49 of the U.K. Road Traffic Act, 1930. Section 48(10) of the Act defined a traffic sign as “all signals, warning signposts, direction posts, signs or other devices”. It was held that the words “or other devices” must be construed ‘ejusdem generis’ the preceding words and, therefore, the white painted line on the road was not a traffic sign. Evans had therefore not committed an offence under the section

APPLIED LAWS

Section 2 of the Interpretation and General Provisions Act defines an “applied law” as:

(a) an Act of the legislature of another country or an order in council of the United Kingdom; or

(b) subsidiary legislation made under any of the foregoing, which is for the time being in force in Kenya.

SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION

This is subordinate or delegated indirect legislation.

subsidiary legislation is ‘any legislative provision (including a transfer or delegation of powers or duties) made in exercise of any power in that behalf conferred by any written law by way of by-law, notice, order, proclamation, regulation, rule of court or other instrument’.

The by-laws, notices, orders, regulations, rules and other ‘instruments’ constitute the body of the laws known as subsidiary legislation.

Although section 30 of the Constitution provides that ‘the legislative power of the Republic (of Kenya) shall vest in the Parliament’, it is not possible for Parliament itself to enact all the laws that are required to run all the affairs of this country.

Many Acts of Parliament require much detailed work to implement and operate them. In such a case the Act is drafted so as to provide a broad framework which will be filled in later by subsidiary legislation made by Government Ministers or other persons under powers conferred on them by the Act.

ADVANTAGES OF DELEGATED LEDISLATION

(a) Compensation of lost Parliamentary time

Parliamentarians are politicians who have to spend much of their time in their constituencies in order to initiative various harambee projects, explain relevant party or government programmes to the people and listen to the problems of their electors. The time so spent constitutes a significant reduction of the time required by Parliament for legislation and this reduction can only be compensated for by delegating some of Parliament’s legislative powers.

(b) Speed

Sometimes an urgent law may be needed. Parliament may not respond to this need, first, because of the slow and elaborate nature of Parliamentary legislative procedure and second, because it is not in session at the material time..

(c) Technicality of subject matter

Parliamentarians are not experts on all matters that may require legislation. It may therefore be advisable, if not inevitable, for Parliament at times to delegate the enactment of laws of a technical nature to Government Ministers who will be assisted by the technical officers in Government Ministries and the Attorney-general’s chambers.

(d) Flexibility

The procedure adopted by Ministers to enact laws are flexible and, as stated above, responsive to urgent needs. The flexibility is a consequence of the fact that they are not governed by the elaborate Standing orders that are an essential feature of parliamentary legislative procedure.

A Minister is free to discuss with his officers, and adopt, the procedure that appears most appropriate in the circumstances.

DISADVANTAGES

Subsidiary or delegated legislation has been criticised for a variety of reasons, the main ones being that it is:

(a) Less democratic

The real or ultimate makers of subsidiary legislation are the technical officers in the various government ministries. These officers have not been elected by the people affected by the laws they make and cannot therefore be made accountable for any undesirable law they make. To that extent, delegated legislation lacks the democratic spirit that usually inspires, and manifests itself in, parliamentary legislation. The people of Kenya can always refuse to re-elect parliamentarians who enacted a law that they feel should not have been enacted but they cannot dismiss the civil servants. Lord Hewart has called this situation “the new despotism”.

(b) Difficult to Control

Although Parliament is theoretically supposed to control subsidiary legislation this is not so in practice. The various rules or regulations made by government ministries are so numerous that Parliament cannot check whether their makers conformed to its intentions or objectives. The question that usually comes to the mind is that, if Parliament is too busy to make the law, how can it have the time to scrutinize it?

- Inadequate publicity

- Sub-delegation and abuse

- Detail and complexity

JUDICIAL CONTROL

The courts can declare any law made as subsidiary legislation to be invalid under the ultra vires doctrine. The law may be declared either substantively or procedurally ultra vires.

(a) Substantive Ultra Vires

A law may be declared substantively ultra vires if the maker had no powers to make it. This may occur in a number of ways. For example, the Minister or Authority may have:

(i) Exceeded the powers given by the Act;

(ii) Exercised the power for another purpose rather than the particular purpose for which it was given, or

(b) Procedural Ultra Vires

A law will be declared procedurally ultra vires if the mandatory procedures prescribed in the enabling Act for its enactment are not followed, such as failure to publish it in the Gazette.

LEGISLATIVE OR PARLIAMENTARY CONTROL

(i) Parliamentary approval

(ii) Ministerial approval

(iii) Publication in the Kenya Gazette

(iv) Circulation of draft rules to interested parties.

(v) Delegation of legislative power to selected persons and bodies

(vi) Prescribes the scope and procedure of law making.

TYPES OF SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION

The definition of subsidiary legislation in s.2 of the Interpretation and General Provisions Act reflects the great variety of nomenclature used by lawyers in relation to delegated legislation. However, the following are the two major groups into which they fall:

(i) By-Laws

By-Laws are usually made by Local Authorities, such as the Mombasa Municipal Council, under the Local Government Regulations Act, 1963. Another example are the by-laws made by the members of co-operative societies under Rule 7 of the Cooperative Societies Rules 1969.

(ii) Rules

Rules are usually made by Government Ministers with the assistance of technical officers employed by their Ministries. An example are the Cooperative Societies Rules, 1969 which were made by the Minister for Co-operative Development under powers conferred on him by s.84 of the Co-operative Societies Act, 1966.

Rules made by Government Ministers may also be called Regulations, Orders, Notices or Proclamations.

(iii) Statutes of General Application

Although there is no authoritative definition of a “statute of general application” the phrase is presumed to refer to those statutes that applied, or apply, to the inhabitants of England generally. In the case of I v I the High Court held that the Married Women’s Property Act 1882 is an English statute of general application that is applicable in Kenya.

These laws are applicable only if:

(a) They do not conflict either with the constitution or any of the other written laws applicable in Kenya, and

(b) The circumstances of Kenya and its inhabitants permit. In I v I the High Court held that the English Married Women’s Property Act 1882 was applicable in Kenya because, in the court’s view, the circumstances of Kenya and its inhabitants do not generally require that a woman should not be able to own property.

APPLICATION OF THE UNWRITTEN SOURCES OF KENYA LAW

It is a rule of Kenya Law that unwritten laws are to be applied subject to the provisions of any applicable written law. This is a consequence of the constitutional doctrine of parliamentary supremacy and the fact that written laws are made by parliament, either directly or indirectly.

When it is said that an unwritten law is applied subject to a written law it does not mean that a written law is more important than an unwritten law. It only means that if any rule of unwritten law (for example, a rule of African customary law) is in conflict with a clause in a written law, the unwritten law will cease to have the force of law from the moment the written law comes into effect.

This rule enables Parliament to make new laws to replace existing customs as social conditions change. It also obviates the possibility of having two conflicting rules of law regarding one factual situation.

An unwritten law that is not in conflict with a written law is as binding as any written law and a breach of it renders what has been done as illegal as if the law broken was a written law.

THE UNWRITTEN SOURCES OF KENYA LAW

Common Law

Common law may be described as that branch of the law of England which was developed by the English courts on the basis of the ancient customs of the English people. Osborn’s law dictionary defines the common law as “that branch of the law of England formulated, developed and administered by the old common law courts on the basis of the common custom of the country”.

It is not the entire common law that is a source of Kenya law but only that portion which the Judicature Act describes as “the substance of the common law”. This presumably means that the writ system and its complex rules of procedure that were developed by the old common law courts for the administration of the common law do not apply to Kenya.

Equity

The word “equity” ordinarily means “fairness” or “justice”. As a source of Kenya law, the phrase “doctrines of equity” means the body of English law that was developed by the various Lord Chancellors in the Court of Chancery to supplement the rules and procedure of the common law. The Lord Chancellors developed equity mainly according to the effect produced on their own individual conscience by the facts of the particular case before them.

Equity was developed as a result of the defects of the common law. The following are some of those defects:

(a) The Writ System

A person intending to commence an action at common law had to obtain a ‘writ’ from the government department that was authorized to issue writs. A writ was a document in the King’s name and under the Seal of Crown commanding the person to whom it was addressed to appear in a specified court to answer the claim made against him by the person at whose request the writ had been issued. However, there were some injuries for which no writs were available at common law owing to the fact that, at that particular time of the common law’s growth, writs could only be issued in a limited number of cases. An example is the tort of nuisance affecting one’s enjoyment of land for which no writ existed at the time. In such cases the injured person could not take the wrongdoer to any of the common law courts and was, as a consequence, left without a remedy for a wrong inflicted. The Lord Chancellor, in the King’s name, intervened and developed remedies for such injuries.

(b) Procedural Technicalities

The procedure in the common law courts was highly technical and many good causes of action were lost due to procedural technicalities. For example, if A sued B because of the tresspass of B’s mare and in his writ A described the mare as a stallion, the action would be automatically dismissed. This led to the urgent craving for a new system of procedure that would dispense justice without undue regard to technicalities.

(c) Delays

Certain standard defences known as “essoins” caused considerable delay before a case could be heard. For example, the hearing of a case could be automatically postponed for a year and a day if the defendant pleaded sickness as a defence even though the court had not verified the truth of the defence. The Lord Chancellor generally disallowed these defences and adopted the maxim “delay defeats equity”

(d) Inadequate remedies

The only remedy available at common law for a civil wrong was financial compensation called damages. This might not be adequate compensation in such cases as breach of contract to sell a piece of land. However, a common law court could not order the defendant to convey the land to the plaintiff. The Lord Chancellor intervened and developed the remedy of “specific performance” for such cases. The Chancellor, in the King’s name would order the defendant to convey the land to the plaintiff.

(e) Non-recognition of trusts

The common law did not recognize “trusts”. For example if A conveyed property to B “on trust” for C the common law courts could not compel B to use the income from the property for the benefit of C. The Lord Chancellor intervened in such cases and the overall effect of the intervention was the development of the body of principles and rules which constitute the basis of the current Law of Trusts. In particular, the Court of Chancery would compel B to use the income from the “trust property” for the benefit of C.

It should be noted that equity is “a gloss upon the common law”. It was developed to supplement the common law but not to supplant it. It does this by, as it were, filling in the gaps left by the common law and, where appropriate, providing alternative remedies to litigants for whom the remedies available at common law are inadequate.

However, the substance of common law and the doctrines of equity are applicable in Kenya only if the circumstances of Kenya and its inhabitants permit and subject to such qualifications or modifications as those circumstances may render necessary.

The English Judicature Act 1873 provided that if there is any conflict between common law and equity, equity is to prevail. However, there is no Kenya statute to that effect. But since the Act appears to be a statute of general application which was in force in England on 12th August, 1897 it is prima facie applicable to Kenya. If so, any conflict between a rule of common law and a doctrine of equity that arises in a Kenya Court would be resolved by applying the doctrines of equity.

Inadequate protection of borrowers

Rigidity or inflexibility

Contributions of Equity

A (i) Developed the so called maxims of equity

(ii) Provided additional remedies

(iii) Provided for the discovery of documents

(iv) Enhanced the protection of borrowers.

(v) Recognized the trust relationship

African Customary Law

African customary law may be described as the law based on the customs of the ethnic groups which constitute Kenya’s indigenous population. Section 3(2) of the Judicature Act 1967 provides that the High Court, the Court of Appeal and all subordinate courts shall be guided by African customary law in civil cases in which one or more of the parties is subject to it or affected by it, so far as it is applicable and is not repugnant to justice and morality or inconsistent with any written law.

These provisions of the Judicature Act may be explained as follows:

(a) Guide

The courts are to be “guided” by African customary law. This provision gives a judge discretion whether to allow a particular rule of customary law to operate or not. The judge is not bound by any rule of customary law and may therefore refuse to apply it if, for example, he feels that it is repugnant to justice or morality.

(b) Civil Case

Customary law is applicable only in civil cases. The District Magistrate’s Court’s Act 1967, S.2 restricts the civil cases to which African customary law may be applied to claims involving any of the following matters only:

(i) land held under customary tenure;

(ii) marriage, divorce, maintenance or dowry;

(iii) seduction or pregnancy of an unmarried woman or girl;

(iv) enticement of, or adultery with, a married woman;

(v) matters affecting status, particularly the status of women, widows and children, including

guardian-ship, custody, adoption and legitimacy;

(vi) intestate succession and administration of intestate estates, so far as it is not governed by any

written law.

(c) Subject to it or affected it

One of the parties must be subject to it or affected by it. If the plaintiff and the defendant belong to the same ethnic group, they may be said to be “subject” to the customs of that ethnic group which could then be applied to settle the dispute. For example, a dispute between Kikuyus relating to any of the matters listed in (b) above cannot be settled under Kamba, Luo or any other customary law except Kikuyu customary law.

However, if there is a dispute involving parties from different ethnic groups it may be determined according to the customs of either party, since the other party would be “affected” by the custom.

(d) Repugnance to justice and morality

The customary law will be applied only if it is not repugnant to justice and morality.

In MARIA GISESE ANGOI v MACELLA NYOMENDA (see Civil Appeal No.1 of 1981 being the judgement of Aganyanya J. delivered at Kisii on 24-5-1982) the High Court held that Kisii customary law which allows a widow who has no children or who only has female children to enter into an arrangement with a girl’s parents and take the girl to be her wife and then to choose a man from amongst her late husband’s clan who will be fathering children for her (i.e. the widow), was repugnant to justice because it denied the alleged wife the opportunity of freely choosing her partner.

The Court refused to follow the custom and declared that there had been no marriage between the appellant and the respondent.

A rule of customary law that might be declared to be repugnant to morality is the Masai custom that a husband returning home and finding an age-mate’s spear stuck at the entrance to his hut, as a means of informing him that the owner of the spear is at the moment having an affair with his wife and he should not interrupt. The husband cannot take divorce proceedings under Masai customs against his wife for adultery. In the event of such a declaration, a Masai man would be able to petition the court for divorce on the ground of the wife’s adultery at common law.

Consistent with the written Law

Islamic law is the law based on the Holy Koran and the teachings of the Prophet Mohammed as explained in his Sayings called “Hadith”.

Islamic law is applicable in Kenya under section 5 of the Kadhi’s Courts Act 1967 when it is necessary to determine questions of Muslim Law relating to personal status, marriage, divorce or inheritance in proceedings in which all the parties profess the muslim religion.

Hindu Law

Hindu customary rites are applicable under S.5 of the Hindu Marriage and Divorce Act, 1960. S.2 of the Act defines a “custom” as “a rule which, having been continuously observed for a long time, has attained the force of law among a community, group or family, being a rule that is certain and not unreasonable, or opposed to public policy; and, in the case of a rule applicable only to a family, has not been discontinued by the family”. Hindu customary rites are a source of Kenya law only for purposes of solemnizing Hindu marriages.

ADMINISTRATION OF THE LAW

THE KENYA JUDICIAL SYSTEM

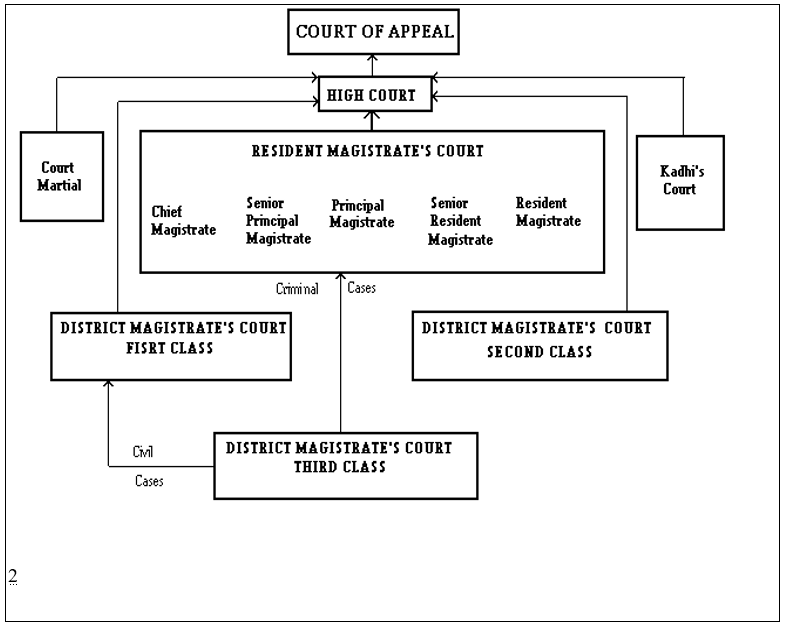

The current Kenya judicial system is organized in the form of a pyramid, with the Court of Appeal at the apex, the High Court immediately below it and then the subordinate courts consisting of the Kadhi’s Court, Resident Magistrate’s Court, District Magistrate’s Court and the Court Martial. This structure of the courts is based on the Constitution, the Magistrate’s Courts Act 1967 and the Kadhi’s Courts Act 1967.

The structure of the Kenya courts may be explained with the aid of the following diagram:

THE COURT OF APPEAL

Establishment

The Court of Appeal was established on 28th October, 1977 by Section 64(1) of the constitution which states that ‘there shall be a Court of Appeal which shall be a superior court of record’.

Composition

judges of the Court of Appeal shall be the Chief Justice and such number, not being less than two, of the judges of appeal … as may be prescribed by Parliament’. The Judicature Act, 1967, s.7(2), as amended by the Statute Law (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act, 1986 provides that the number of judges of appeal shall be eight.

Jurisdiction

Court of Appeal ‘shall have such jurisdiction and powers in relation to appeals from the High Court as may be conferred on it by law’.

Provides that ‘the Court of Appeal shall have jurisdiction to hear and determine appeals from the High Court in cases in which an appeal lies to the Court of Appeal under any law’.

Procedure

The practice and procedure of the Court of Appeal are regulated by Rules of Court made by the Rules Committee constituted under the Appellate Jurisdiction Act.

Provides that an uneven number of at least three judges shall sit for the final determination of an appeal other than the summary dismissal of an appeal.

Where more than one judge sits for the determination by the court on any matter (whether final or otherwise), the decision of the court shall be according to the opinion of a majority of the judges who sat for the purpose of determining that matter.

The Court of Appeal has no original jurisdiction and hears appeals from the High Court only.

THE HIGH COURT

Establishment

The High Court is established by S.60 (1) of the Constitution which states that ‘there shall be a High Court, which shall be a superior court of record’.

Composition

The Constitution provides that the judges of the High Court shall be the Chief Justice and such number, not being less than thirty-two, of other judges as may be prescribed by Parliament.

The Chief Justice is to be appointed by the President while the other judges (known as “puisne judges”) are appointed by the President acting in accordance with the advice of the Judicial Service Commission.

Jurisdiction

The High Court shall have ‘unlimited original jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters and such other jurisdiction and powers as may be conferred on it by the constitution or any other law’.

Although the jurisdiction of the High Court is unlimited it will in practice only serve as a trial court for civil cases in which the amount claimed is more than Shs.300,000 and cannot therefore be heard in any Resident Magistrate’s Court.

(a) Interpretation of Constitution

The Constitution provides that where any question as to the interpretation of the constitution arises in any proceedings in any subordinate court, and the court is of the opinion that the question involves a substantial question of law, the court may, and shall if any party to the proceedings so requests, refer the question to the High Court. For purposes of determining the question referred, it shall be composed of an uneven number of judges, not being less than three.

The decision of the High Court binds the Court that referred the question to the High Court and it must dispose the case in accordance with the High Court’s decision.

(b) Supervisory Jurisdiction

The High Court has jurisdiction under S.65 (2) of the Constitution to supervise any civil or criminal proceedings before any magistrate’s court or court-martial and can make such orders, issue such writs and give such directions as it may consider appropriate for the purposes of ensuring that justice is duly administered by such court.

(c) Admiralty Jurisdiction

The High Court is constituted a court of admiralty by S.4 of the Judicature Act for the purpose of exercising ‘admiralty jurisdiction in all matters arising on the high seas or in territorial waters, or upon any lake or other navigable inland waters in Kenya’. The law applicable to such cases is the Admiralty of England as well as ‘international Laws and the comity of nations’.

(d) Presidential and Parliamentary election petitions.

(e) Enforcement of fundamental rights and freedoms

RESIDENT MAGISTRATE’S COURT

Establishment

The Resident Magistrate’s Court is constituted by S.3 (1) of the Magistrate’s Courts Act which provides that ‘there is hereby established the Resident Magistrate’s Court, which shall be a court subordinate to the High Court and shall be duly constituted when held by a Chief Magistrate, a Senior Principal Magistrate, a Principal Magistrate, a Senior Resident Magistrate or a Resident Magistrate’.

Civil Jurisdiction

The civil jurisdiction of the Resident Magistrate’s Court was increased by the Statute Law (Miscellaneous Amendments) Acts of 1983, 1986 and 1991 and is as follows:

Court Jurisdiction

Court Held by a chief Magistrate, a Senior Value of subject matter does not

Principal Magistrate, Principal Magistrate exceed Shs. 50,000/-.

No jurisdiction

or a Senior Resident Magistrate under African customary law

Court Held by a Resident Magistrate Value of subject matter does not

exceed Shs.25,000/-

Has unlimited Subject-matter

jurisdiction in claims based on

African Customary law

The Chief Justice is empowered, by notice in the Gazette, to increase the limit of jurisdiction of:

- a Chief Magistrate or Senior Principal Magistrate to a sum not exceeding50000/=; and

- a Principal Magistrate, Senior Resident Magistrate or to a sum not exceeding300,000/=

- Resident Magistrate not exceeding Ksh 75,000/=

Criminal Jurisdiction

The Criminal Procedure Code, as amended by the Statute Law (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act 1986, provides that a subordinate court held by a Chief Magistrate, a Senior Principal Magistrate Principal Magistrate or Senior Resident Magistrate may pass any sentence authorised by law for an offence triable by that court.

DISTRICT MAGISTRATE’S COURT

Establishment

District Magistrate’s Courts are established for each district in Kenya by S.7(1) of the Magistrate’s Courts Act 1967.

Constitution

Section 7(1) of the Act provides that a district magistrate’s court ‘shall be duly constituted when held by a district magistrate who has been assigned to the district in question by the Judicial Service Commission’.

Territorial Jurisdiction

Section 7(3) of the Act provides that ‘a district magistrate’s court shall have jurisdiction throughout the district in respect of which it is established’. However, the Chief Justice may, by notice in the Gazette, extend the areas of jurisdiction of a district magistrate by designating any two or more districts a joint district.

Criminal Jurisdiction

The Statute Law (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act 1983 amended the criminal jurisdiction of the district magistrate’s courts and imposed the following new limits:

Class Imprisonment Fine Strokes

First Class 7 years Shs.20,000 24

Second Class 2 years Shs.10,000 12

Third Class 1 year Shs. 5,000 6

The criminal jurisdiction of any magistrate may be increased by the Judicial Service Commission by notice in the Gazette.

Criminal Appeal

Section 10(1) of the Magistrate’s Courts Act provides that any person who is convicted of an offence on a trial held by a magistrate’s court of the third class may within fourteen days appeal against his conviction or sentence, or both, to the Resident Magistrate’s Court. There is no right of appeal for a person who pleaded guilty and was convicted on the plea, except as to the legality or extent of the sentence. Where a person charged with an offence has been acquitted the Attorney General may appeal against the acquittal.

Civil Jurisdiction

The civil jurisdiction of the district magistrate’s courts in claims not under customary law was changed by the Statute Law (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act 1983 and are as follows:

District Magistrate Maximum Claim

First Class Shs.10,000

Second Class Shs. 5,000

Third Class Shs. 5,000

There is no limit on the amount if the proceedings concern a claim under customary law.

Civil Appeals

S.11 (1) of the Magistrate’s Court Act provides that ‘any person who is aggrieved by an order of a magistrate’s court of the third class made in proceedings of a civil nature may appeal against the order to a magistrate’s court of the first class’. The appeal must be made within twenty-eight days after the date of order appealed against.

KADHI’S COURT

Establishment

The Kadhi’s Courts Act, 1967, S.4 (1) as amended by the Statute Law (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act 1986 provides that “in pursuance of section 66(3) of the Constitution there shall be established such number of Kadhi’s Courts as the Chief Justice may, in consultation with the Chief Kadhi, determine”.

Territoral Jurisdiction

The Kadhi’s Courts Act, S.4 (2) provides that the Kadhi’s court shall have jurisdiction as follows:

- Three courts each have jurisdiction within Kwale District, Mombasa District, Kilifi District and Lamu District.

- One court each have jurisdiction within Nyanza Province, Western Province, West Pokot District, Trans Nzoia District, Elgeyo Marakwet District, Laikipia District, Baringo District, Uasin Gishu District, Kericho District, Nakuru District and Nandi District.

- One court has jurisdiction within Wajir District and Mndera District.

- One court has jurisdiction within the Nairobi area and the Central and Eastern Provinces (except Marsabit and Isiolo District).

- One court has jurisdiction in Garrisa District and Tana River District.

- One court has jurisdiction in Marsabit District and Isiolo District.

This makes a total of eight Kadhi’s courts.

Civil Jurisdiction

Section 65(1) of the Constitution states that ‘the jurisdiction of a Kadhi’s court shall extend to the determination of questions of Muslim law relating to personal status, marriage, divorce or inheritance in proceedings in which all the parties profess the Muslim religion.”

Criminal Jurisdiction

Kadhi’s Courts have no criminal jurisdiction.

COURT-MARTIAL

Establishment

Section 65 (1) of the Constitution empowers Parliament to establish court martial which shall have such jurisdiction and powers as may be conferred by any law. Pursuant to this provision, the Armed Forces Act, S.85 (1) provides that ‘a court-martial may be convened by the Chief of General Staff or by the Commander’. The court-martial is not a permanent court but is convened from time to time to try any person who has committed an offence which, under the Section 84 of the Armed Forces Act, is triable by a court martial. The court is dissolved as soon as the trial is over.

Appeals

Section 115 of the Armed Forces Act allows a person who has been convicted by a court-martial to appeal to the High Court either against the conviction, sentence or both. The Attorney General may also appeal to the High Court within forty days of an acquittal.

S.115 (3) of the Act states that the decision of the High Court on any appeal under the Act shall be final and shall not be subject to further appeal.

SPECIAL COURTS

There exist in Kenya a number of other institutions which are called “courts” or “tribunals”, but which do not form part of the Kenya judicial system.

They are called “courts” because they exercise judicial or quasi-judicial powers by hearing particular types of disputes or cases. Technically, however, these institutions are not courts because they do not administer the law. For example, when a trade union refers a dispute between its members and their employers to the Industrial Court, the Court will settle the dispute by following a procedure which approximates to the procedure followed in a court of law. This is done primarily as a means of ensuring that each of the parties to the dispute will be satisfied that it has been given a fair opportunity to present its case. However, if the court decides to award a salary increase for the employees, it would not be applying, or administering, a rule of law.

This is so because there is no legal rule which contains, or provides a mechanism for determining, the salary scales for any class of workers in Kenya. Additionally, the decision cannot be challenged by recourse to the appellate jurisdiction of any of the courts within the judicial system. The major examples of such tribunals are:

(i) The Industrial Court;

(ii) The Rent Tribunal, and

(iii) The Business Premises Rent Tribunal.

CASE LAW AND JUDICIAL PRECEDENT

“Case law” may be described as the method or way of learning law “through the cases”. By studying a particular case and the decision therein, we get to know the legal rules relating to the factual situation of the case. The more cases we learn the more we are “learning the law”.

THE DOCTRINE OF “STARE DECISIS” OR JUDICIAL PRECEDENT

The doctrine of “stare decisis” or “judicial precedent” is a legal rule that requires a judge to refer to earlier cases decided by his predecessors in order to find out if the material facts of any of those cases are similar to the material facts of the case before him and, in the event of such a finding, to decide the case before him in the same way as the earlier case had been decided. In this way, the earlier decision “stays” or “stands” as it was made.

The doctrine has been described as the “sacred principle” of English law. It was developed by the English courts as a mechanism for the administration of justice which would enable judges to make decisions in an objective or standard manner instead of subjectively and in a personalised manner.

“RATIO DECIDENDI”

The “ratio decidendi” of a case consists of the material facts of the case and the decision made by the judge on the basis of those facts. The material facts become, as it were, the basis or “rationale” (ratio) upon which the judge is to decide (decidendi) the case. They constitute, in ordinary parlance, the reason, or ground, of the judge’s decision and ensure that the decision-making process is a rational one.

The ratio decidendi of a decided case constitutes the legal rule, or principle, for the decision of future cases with similar material facts. In other words, the decision is a precedent to be followed when deciding such cases.

TYPES OF PRECEDENTS

(a) An binding precedent the judge must follow whether he approves of it or not. It is binding upon him and excludes his judicial discretion for the future. These, generally speaking, are decisions of higher courts.

(b) A persuasive precedent if it is one which the judge is under no obligation to follow but may however take into consideration, or follow, in the course of considering his intended decision. These, generally speaking, are decisions of lower courts and the decisions of superior courts in the Commonwealth.

A precedent may also be classified as:

(i) An original precedent if it is one which creates and applies a new legal rule; or

(ii) A declaratory precedent if it is one which does not create a new legal rule but merely applies an existing legal principle.

The latter classification is a technical one which does not fall within Hale’s definition of a “declaratory precedent”. According to Hale, “the decisions of courts of justice (in England)… do not make a law properly so-called: for that only the King and Parliament can do; yet they have a great weight and authority in expounding, declaring, and publishing what the law is”.

Salmond however contends that “both at law and in equity, however, the declaratory theory (as formulated by Hale) must be totally rejected if we are to attain to any sound analysis and explanation of the true operation of judicial decisions. We must admit openly that precedents make law as well as declare it. We must admit further that this effect is not merely accidental and indirect, the result of judicial error in the interpretation and authoritative declaration of the law. Doubtless judges have many times altered the law while endeavouring in good faith to declare it. But we must recognise a distinct law-creating power vested in them and openly and lawfully exercised. Original precedents are the outcome of the intentional exercise by the courts of their priviledge of developing the law at the same time that they administer it”.

OBITER DICTUM

A “by the way” statement made by a judge before delivering his judgement with a view to re-enforcing or strengthening his reasons for the decision that he will make is known as “the obiter dictum” of the case. If more than one such statements are made, they are known as obiter dicta. An obiter dictum is defined by Osborne’s Concise Law Dictionary as “an observation by a judge on a legal question suggested by a case before him, but not arising in such a manner as to require decision”.

Although an obiter dictum does not constitute a legal rule for the decision of future cases it may constitute a “persuasive precedent” for a relevant later case. In other words, it may be used by an advocate to “persuade” a judge hearing a case to accept as a legal rule the view it expresses.

STARE DECISIS AND ITS APPLICATION BY THE KENYA COURTS

There is so far no case decided by the Kenya Court of Appeal regarding the application of “stare decisis” by Kenya Courts. What we have are the rules which were formulated in 1970 by the then Court of Appeal for East Africa at the time that it was also the Court of Appeal for Kenya. However, it can be assumed that the rules which the Court of Appeal for East Africa laid down for Kenya Courts in Dodhia v. National & Grindlays Bank are still binding on the Kenya Courts (with the probable exception of the Kenya Court of Appeal)

These rules are:

(i) Subordinate courts are bound by the decisions of superior courts.

To understand the full implications of this statement you should have the diagram of the Kenya courts in front of you.

(ii) A subordinate court of appeal should be bound by a previous decision of its own.

Subordinate courts of appeal are the High Court, Resident Magistrate’s Court, Senior Resident Magistrate’s Court, Principal Magistrate’s Court, Senior Principal Magistrate’s Court, the Chief Magistrate’s Court and the First Class District Magistrate’s Court. These courts are “subordinate” because they have higher courts above them. However, they are “courts of appeal” because they hear appeals from the courts below them.

(iii) As a matter of judicial policy, the final court of appeal, while it would normally regard a previous decision of its own as binding, should be free in both civil and criminal cases to depart from such a previous decision when it appears right to do so.

(a) Erroneous or improper conviction

in criminal cases, if following the earlier decision would result in an improper conviction;

(b) Changes in circumstances

if there have been rapid changes in the customs, habits and needs of the people, since the earlier case was decided, so that these changes should be reflected in the decision of the final court of appeal, and

(c) Per incurriam rule

if it is satisfied that the earlier decision was given “per incuriam”. The court did not however explain what would constitute a “per incuriam” decision. However, in MILIANGOS v GEORGE FRANK (TEXTILES) LTD the English House of Lords stated that a decision is only per incuriam where:

(i) the judgment was given in inadvertence to some authority (judge-made, statutory or regulatory) apparently binding in the court giving such judgment, and

(ii) if the court giving such judgment had been advertent to such authority, it would have decided otherwise than it did (i.e. it would, in fact, have applied the authority)

ADVANTAGES OF STARE DECISIS

(i) Certainty and Predictability

The doctrine of stare decisis introduces an element of certainty and uniformity in the administration of justice.

(ii) Flexibility

Because of the freedom that the final Court of Appeal usually has to depart from a previous decision of its own if the social conditions that necessitated such decision no longer exist, there is flexibility in the administration of the law as human societies grow and become more complex

(iii) Aptitude for growth

The process of ‘distinguishing’ cases facilitates the growth of detailed legal principles to deal with different factual situations. This would probably not be possible in a purely enacted system of law.

A case is ‘distinguished’ if a judge points out the difference in the material facts of an earlier case and the case before him for decision, as the basis for arriving at a different decision.

(iv) Practicality

The case law method has enabled judges to adopt a practical approach to legal problems since such problems have arisen from the practical situations in which the litigants have found themselves. This practical approach has also enabled judges to make decisions only after being satisfied that the particular decision would not create practical problems for the people subject to the law

- Rich in detail

- Consistency and uniformity

ADVANTAGES OF STARE DECISIS

(i) Rigidity

The case law method of administration of justice has been criticized on the grounds that it leads to rigidity, since the discretion of a judge is usually restricted by the rule that he must follow the decision of his predecessors if the material facts of the case to be decided are the same as those of an earlier case.

(ii) Over-subtlety/Artificiality

Because a judge is forced, as it were, to follow an earlier case which his conscience may preclude him from following, he might be inclined to ‘distinguish’ the present case from the earlier case. This artificial ‘distinguishing’ sometimes creates artificial differences which make case law over-subtle.

(iii) Bulk and Complexity

Because so many cases are being decided everyday by courts all over the country, case law has become bulky and complex and it is doubtful whether judges would really know if a relevant earlier case had been decided, say some ten years ago.

(iv) Piece-meal :Rules of law are made in bits and pieces

THE LEGAL PROFESSION

Magistrates

A magistrate is an advocate who is appointed by the Judicial Service Commission to the post of –

(a) District Magistrate, or

(b) Resident Magistrate.

With the passage of time, he may be promoted to the rank of:

- Senior Resident Magistrate,

- Principal Magistrate,

- Senior Principal Magistrate, or

- Chief Magistrate.

Due to historical reasons, a substantial number of the current District Magistrates are “lay magistrates’ who are neither law graduates nor advocates. However, this situation is likely to be reversed in the near future following the implementation in 1993 of a new scheme of service for Magistrates and Judges.

Judges

Generally speaking, judges of the High Court of Kenya are appointed from among advocates of at least seven years’ standing (i.e. those advocates who have been in private practice for at least seven years). They are called “puisne judges“.

All judges are appointed by the president in accordance with the advice of the Judicial Service Commission.

Their appointment is already explained in paragraph 1.8.3

Qualifications

To qualify for appointment as a judge of the High Court a person must either be:

(a) An advocate of the High Court or

(b) Be or have been a judge of a court with unlimited jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters in some part of the common Wealth or Republic of Ireland.

(c) Or have been a judge of a court with jurisdiction to hear appeals from a court with unlimited jurisdiction in criminal and civil matters in some part of the common Wealth or Republic of Ireland.

Under section 63 of the Constitution a judge must take and subscribe the oath of allegiance and any oath as may be prescribed by Parliament, before taking duties.

All judges retire at the age of 74 and enjoy some security of tenure of office.

Under the Constitution a judge can only be removed from office on the ground of

- Misbehaviour or,

- Inability to discharge the functions of his office.

Provided a tribunal appointed by the President has investigated the allegations as a mere of fact and recommended that the judge is suspended from office, but such suspension ceases to have any effect if the tribunal recommends the judge to remain in office. However, the suspension becomes permanent if the tribunal recommends that the judge be removed from the office.

Judges of Appeal

A “judge of appeal” is a judge who is appointed to the Court of Appeal,

Registrar of the High Court

The Registrar of the High Court is the administrative head of the High Court. He is assisted in his duties by the Deputy Registrar of the High Court.

The CHIEF JUSTICE

The office of the Chief Justice is created by the constitution

Appointment

Under section 61 of the Constitution the Chief Justice is appointed by the President.

Functions

- Administrative Function

- He is the principal administrative officer of the judiciary

- He is the chairman of the Judicial Service Commission

- He determines where the High court sits

- He appoints the duty judge

- Assigns cases to judges

- He is in charge of discipline

- Judicial Function

As a judge of the High Court and court of Appeal he participates in the adjudicatory process.

(c) Legislative Function

He is empowered to make law to facilitate the administration of Justice.

He is empowered to make rules to regulate administration of justice in subordinate cour

He is empowered to make rules to facilitate the enforcement of fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual.

(d) Political function

The chief justice administers the presidential oath to the person who is elected as president.

He represents the judiciary in all state functions.

(e) Legal education and profession

- The chief justice is the chairman of the council of legal education.

- He admits advocates to the ban.

- He issues practicing certificates to advocates.

- He appoints commissioners for oath and Notaries Public.

(f) Enhancement of Jurisdiction of Magistrates

Under the provisions of the magistrate court the Chief Justice is empowered to enhance or increase the civil jurisdiction of the Resident Magistrates Court.

HIGH COURT REGISTRARS

These are magistrates who in addition to judicial functions perform administrative duties. They are appointed by the Judicial Service Commission. They are administrative and accounting officers.

They assist the Chief Justice in the administration of the judicial department and are answerable to the Chief Justice. However the High Court Registrar is the custodian of the Roll of Advocates.

KADHI

The chief Kadhi and all Kadhis are appointed by the judicial service commission.

To qualify for appointment one must:

- Profess Muslim faith.

- Possess such knowledge of Muslim law applicable to any sect of sects of Muslims which in the opinion of the J S C qualify one for appointment.

- Kadhis retire at 55 years.

- They preside over Kadhis Courts only.

Attorney generaL

The Attorney General is appointed by the president.

To qualify for appointment one must be an advocate of the High Court if not less than 5 years standing.

The Attorney General retires at such age as may be prescribed by the parliament.

He enjoys the same security of tenure of office.

He can only be removed for incapacity of misbehaviour provided a tribunal appointed by the president so recommends after investigation of the allegations.

Powers of the Attorney General

- Institute and undertake criminal proceedings against any person before any court other than a court martial for any alleged offence.

- Take over and continue any criminal proceedings instituted by any other person or body.

(c) Discontinue as any stage before judgement is delivered any criminal proceedings instituted or undertaken by himself or any other person or body, by entering the so called Nolle Prosecuice “I refuse to prosecute”

(d) Order the commissioner of police to investigate any alleged or suspected criminal acts. The commissioner must oblige and report to the Attorney General.

Functions

- Under sec 26( 2) the Attorney General is the principal legal adviser to the government of Kenya

- He occupies a ministerial post in the cabinet

- Must act independently in the discharge of his duties

- Drafts all government bills

- He is an ex-officio member of the National Assembly

- Represents the state in all cases

- He is a public prosecutor

- Most senior lawyer (head of the bar)

- Services legal needs of other government departments

- Member of the judicial service commission

- Member of the Advisory Committee on prerogative of mercy

Advocates

An advocate is a person whose name has been duly entered as an advocate in the Roll of Advocate.

An advocate has also been defined as a person who has been admitted as such by the Chief Justice. The law relating to Advocacy is contained in the Advocates Act.

Qualifications

To qualify for admission as an advocate one must

- Be a Kenyan citizen

- Possess a law degree from a recognized university

- Satisfy the council of Legal Education Examination Requirements.

Procedure for Admission

- A person must make a formal petition to the chief justice through the registrar of high court.

- A copy of the petition must be delivered to the council of legal Education.

- A notice of the petition must also be given. The petition must be published in the Kenya Gazette.

- The petition is heard by the Chief Justice and subsequently the petitioner takes the oath of office and signs the role of advocates.

To practise law one must have a practicing certificate.

Duties of an Advocate

- Duty to the Court

As an officer of the court an advocate is bound to assist in the administration of justice. He must advice evidence, the law correctly each time he appears before the court.

- Duty to Client

He is bound to urge his clients’ case in the best manner possible. He owes a legal duty of care to the client and is liable in damages for professional negligence.

- Duty to the Profession

He is bound to maintain the highest possible standard of conduct and integrity by obedience to the law and ethics of the profession.

- Duty to the Society

As a member of the society he is bound to take part in its social and political and economic development.