Industrialization

In its broadest sense, industry is any work that is undertaken for economic gain and that promotes employment. The word may be applied to a wide range of activities, from farming to manufacturing to tourism. It encompasses production at any scale, from the local—sometimes known as cottage industry—to the multinational or transnational. In a more restricted sense, industry refers to the production of goods, especially when that production is accomplished with machines. It is this limited definition of industry that is

embodied by the notion of industrialization: the transition to an economy based on the largescale, machine-assisted production of goods by a concentrated, usually urban, population of workers. Manufacturing, which literally means “making by hand”, has come to describe mechanical production in factories, mills, and other industrial plants

Classifying Industry

An industry is usually classified as belonging to one of the following four groups:

- Primarily

- Secondary

- Tertiary

- Quaternary.

Primary industries, which collect or extract raw materials, are located where the resources are found.

Secondary industries are those that process or convert the raw materials into finished products. Some of these manufacturing industries must be situated close to the raw materials they use, others are tied to their largest markets, and still others—independent of both resources and markets—are often located wherever it is cheapest at the time.

Tertiary industries are the service industries. These include retailing, wholesaling, transport, public administration, and the professions, such as law.

Quaternary industries comprise activities that provide expertise and information. Consultancy services and research organizations belong to this category. These are generally market oriented, but since electronic communication permits swift contact and the easy

transmission of data, they may be located almost anywhere.

Industrial Transition

Changes to the industrial structure of a country can be measured using either the value of manufactured output or alterations to the employment structure. For the established industrial nations, there has been a clear shift in the relative importance of different types of industry, and this has been accompanied by a change in employment. Since the mid-19th century, the proportion of the US workforce employed in primary industry has declined from about 70 per cent to its present level of just 3 per cent. Employment in secondary industry reached a peak of 30 per cent in the 1950s, after which it dropped back to 23 per cent. Tertiary and quaternary industries now employ 74 per cent of the workforce.

The corresponding figures for the UK are nearly identical: primary industry has just 2 per cent, secondary 23 per cent, and tertiary and quaternary 75 per cent of the workforce. In Germany, the distribution is 3 per cent in primary industry, 37 per cent in secondary, and 60 per cent in tertiary and quaternary.

These figures stand in marked contrast to those of the Emerging and Less Developed Ccountries (ELDCs). In India, for example, 65 per cent of the workforce is engaged in primary industry, 19 per cent in secondary, and 11 per cent in tertiary. Not all ELDCs display similar figures, however-much depends on their history and their links with the rest of the world. In Nigeria and South Africa, for example, approximately 44 per cent and 50 per cent of the workforce respectively is engaged in tertiary activity.

De-industrialization

De-industrialization describes the decline in the contribution made by manufacturing industry to a nation’s overall economic prosperity. The process might better be termed reindustrialization, because the shift is not away from industry altogether, but from secondary to tertiary and quaternary industry. In other words, a de-industrializing economy moves away from the manufacture of goods and towards the provision of services. Those countries to industrialize first—the UK, France, and the United States—are now

undergoing de-industrialization. The ascendancy of the service economy in the context of the post-industrial society is characterized by a number of apparently negative features, such as a decline in manufacturing employment and a dependence on imports across a wide range of sectors.

Although the loss of the manufacturing base is likely to create unemployment at first, it may not be an adverse development in the long term. Ironically, de-industrialization in the three countries mentioned above has been accompanied by a growth in the high-tech industries in areas such as the Côte d’ Azur in France; Silicon Valley in California; and along the M4 motorway, around Cambridge, and in central Scotland—the so-called Silicon Glen—in the UK. The long-term impact of de-industrialization has yet to be felt. It may be the speed of the process, rather than the process itself, that needs careful management.

Transnational Corporations

Probably the most significant industrial development since the 1960s has been the rise of the multinational or transnational company. Examples of these companies, which operate in many countries, are Ford, General Motors, IBM, Siemens, and Matsushita Electrical. United Nations (UN) estimates that investment by transnational companies has risen by 13 per cent per year over the last 20 years, largely because more and more governments are accepting these firms into their countries. Nevertheless, the growth of multinational corporations has raised a number of concerns. An enormous amount of production power is concentrated in the hands of a few controllers, which means that the countries involved become directly susceptible to economic changes in other parts of the world. The transfer of assets from one country to another may be difficult for governments to manage or prevent, and there are likely to be disparities in the treatment of different countries.

Manufacturing countries experiencing the decline of home-based industry, such as the UK, have proved attractive targets for multinationals. So have countries in Asia and South America, where energy and labour are relatively inexpensive. By contrast, few African countries have benefited from investment by transnational corporations because of the general lack of skilled workforce and adequate infrastructure. Not all transnational have their origins in the developed nations. The development of such companies is encouraged in the NICs as a means of securing expanding export markets.

Consequences of Industrialization

Most countries regard industrialization as a positive development capable of generating rapid wealth, revitalizing run-down areas, and conferring influence in world affairs. Most also now recognize the need for a diversified industrial base to safeguard their economies from fluctuations in the market price for their own specialized product. Industrialization schemes commonly require a parallel development of energy sources. In the case of hydroelectric plants, there is social dislocation, since large areas may be flooded to

create the necessary water reserves behind the so-called super-dams.

Environmental safeguards may be overlooked, leading to serious problems of air, land, and water pollution. One of the worst incidents occurred in Minamata, Japan, where mercury residues from nearby chemical plants contaminated the water of Minamata Bay, were ingested by fish, and then entered the human food chain to cause death and illness for up to 30 years after the event. Another notorious example was Bhopal, India, where a leak of poisonous gas killed thousands of people and blinded or otherwise injured many others.

In Europe, the North Sea is suffering from the effects of industrial waste, thermal pollution from power stations, atmospheric fallout containing high levels of lead, oil spilled form ships, and radioactive materials from nuclear power stations. Increasing industrialization means that pressures to conserve resources are rising. Urbanization and associated problems such as housing, crime unemployment etc

The Future of Industry

Several trends are likely in the global pattern of industrialization. First, only certain countries, and not the world as a whole, may experience a post-industrial future. A second trend will be the efficient and careful use of resources and the growth in recycling as the concept of sustainability becomes better established. Recycling industries are a growth area themselves, and established manufacturers are increasingly operating product recycling schemes. A final trend will be the growing need for alternative technologies to reduce the consumption of resources for industrial production and to protect the natural environment. Worldwide cooperation will be necessary if all nations are to gain from the potential benefits of industry.

Modernization

Modernization is a concept used in sociology and politics. It is the view that a standard, teleological (the explanation of phenomena by the purpose they serve rather than by postulated causes) evolutionary pattern, as described in the social evolutionism theories, exists as a template for all nations and peoples

According to theories of modernization, each society would evolve inexorably from barbarism to ever greater levels of development and civilization. The more modern states would be wealthier and more powerful, and their citizens freer and having a higher standard of living. According to the Social theorist Peter Wagner, modernization can be seen as processes, and as offensives.

The former view suggests that it is developments, such as new data technology or dated laws, which make modernization necessary or preferable. This view makes critique of modernization difficult, since it implies that it is these developments which control the limits of

human interaction, and not vice versa.

The latter view of modernization as offensives argues that both the developments and the altered opportunities made available by these developments are shaped and controlled by human agents. The view of modernization as offensives therefore sees it as a product of human planning and action, an active process capable of being both changed and criticized. This was the standard view in the social sciences for many decades. It was also viewed as a “development of the rational and universal mind towards self-consciousness and freedom.” This theory stressed the importance of societies being open to change and saw reactionary forces as restricting development. Maintaining tradition for tradition’s sake was thought to be harmful to progress and development.

This approach has been heavily criticized, mainly because it conflated modernization with westernization. In this model, the modernization of a society required the destruction of the indigenous culture and its replacement by a more westernized one.

Technically modernity

simply refers to the present, and any society still in existence is therefore modern. Proponents of modernization typically view only Western society as being truly modern arguing that others are primitive or ‘unevolved’ by comparison. This view sees ‘unmodernized’

societies as inferior even if they have the same standard of living as western societies. Opponents of this view argue that modernity is independent of culture and can be adapted to any society. Japan is cited as an example by both sides. Some see it as proof that a

thoroughly modern way of life can exist in a non-western society. Others argue that Japan has become distinctly more western as a result of its modernization. In addition, this view is accused of being Eurocentric, as modernization began in Europe with the industrial revolution.

Science and Technology and Development

Science is the intellectual and practical activity encompassing the systematic study of the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world through observation and experiment, while technology is the application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes

Over the past 150 years, progress in science and technology has been a key driver of human and societal development, vastly expanding the horizons of human potential and enabling radical transformations in the quality of life enjoyed by millions of people. The harnessing of modern sources of energy counts among the major accomplishments of past scientific and technological progress. And expanding access to modern forms of energy is itself essential to create the conditions for further progress. All available forecasts point to continued rapid growth in global demand for energy to fuel economic growth and meet the needs of a still-expanding world population. It is useful to distinguish between several generally accepted phases of technological evolution, beginning with basic scientific research and followed by development and demonstration, RD&D. When all goes well, RD&D is followed by a ‘third D’—the

deployment phase— wherein demonstrated technologies cross the threshold to commercial viability and gain acceptance in the marketplace.

Typically, government’s role is most pronounced in the early research and development phases of this progression while the private

sector plays a larger role in the demonstration and deployment phases. Nevertheless, government can also make an important contribution in the demonstration and early deployment phases, for example, by funding demonstration projects, providing financial

incentives to overcome early deployment hurdles, and helping to create a market for new technologies through purchasing and other policies.

Many demonstrated technologies encounter significant market hurdles as they approach the deployment phase; for some—hybrid vehicles, hydrogen as a transport fuel, solar energy, coal-based integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC), and fuel cells— cost rather than technological feasibility becomes the central issue. Established private-sector stakeholders can be expected to resist, or even actively undermine, the deployment of new technologies, thus necessitating additional policy interventions.

Participatory Development

The meaning of “participation” is often a rendition of the organizational culture defining it. Participation has been variously described as a means and an end, as essential within agencies as it is in the field and as an educational and empowering process necessary to

correct power imbalances between rich and poor. It has been broadly conceived to embrace the idea that all “stakeholders” should take part in decision making and it has been more narrowly described as the extraction of local knowledge to design programs off site. Differences in definitions and methods aside, there is some common agreement concerning what constitutes authentic “participation”.

Participation is involvement by a local population and, at times, additional stakeholders in the creation, content and conduct of a program or policy designed to change their lives. Built on a belief that citizens can be trusted to shape their own future, participatory development uses local decision making and capacities to steer and define the nature of an intervention. Participation requires recognition and use of local capacities and avoids the imposition of priorities from the outside. It increases the odds that a program will be on target and its results will more likely be sustainable.

Ultimately, participatory development is driven by a belief in the importance of entrusting citizens with the responsibility to shape their own future, systems and as resources, from salaries to food parcels and reconstruction materials are delivered. With no awareness of social or political context it is never certain if an intervention is warranted at all. And when there is blind engagement, ignorance of context makes each choice a round of roulette, potentially explosive and liable to overrun the self-development potential of the target population while undermining the effectiveness of assistance delivery in the first place. At worst, we aid and abet the violence and become accomplices to adversity. Participatory methodologies, as part of political development programs or not, increase awareness of the social and political context and better the odds this will be avoided.

Four separate studies of participatory programming have found that such methods often cost less in the long run and are consistently more effective at getting assistance where it needs to go. Such methods were also found to be unmatched in fostering sustainability, strengthening local self-help capacities and in improving the status of women and youth. Finally, by establishing platforms where organizations may access and involve citizens in their programs, participatory development methods often extended the reach of traditional development approaches by leveraging local resources with national and foreign assets.

Benefits of Participatory Development

Coverage- to reach and involve on a wider scale the disadvantaged rural people through institution building that is the creation of adequate “receiving” systems at grassroots level as well as of corresponding “delivery” systems Efficiency- to obtain a cost-efficient design and implementation of a project. The beneficiaries will contribute more in project planning and implementation by providing ideas, manpower, labour and/or other resources (cost-sharing). Consequently project resources are used more efficiently

Effectiveness- the people involved obtain a say in the determination of objectives and actions, and assist in various operations like project administration, monitoring and evaluation. They obtain also more opportunities to contribute their indigenous knowledge of the local conditions to the project and thus facilitate the diagnosis of environmental, social and institutional constraints as well as the search for viable solutions;

Adoption of innovations- the beneficiaries can develop greater responsiveness to new methods of production, technologies as well as services offered;

Production- higher production levels can be achieved while ensuring more equitable distribution of benefits;

Successful results- more and better outputs and impact are obtained in a project and thus

longer-term viability and more solid sustainability. By stressing decentralization, democratic

processes of decision-making and self-help, various key problems can be better solved, including recurrent costs, cost-sharing with beneficiaries as well as operation and maintenance;

Self-reliance- this broad, ultimate objective embraces all the positive effects of genuine participation by rural people. Self-reliance demolishes their over-dependency attitudes, enhances awareness, confidence and self-initiative. It also increases people’s control over

resources and development efforts, enables them to plan and implement and also to participate in development efforts at levels beyond their community Supporting institutions like government agencies and NGOs can fulfill better their mandates

National Sustainable Development Strategies

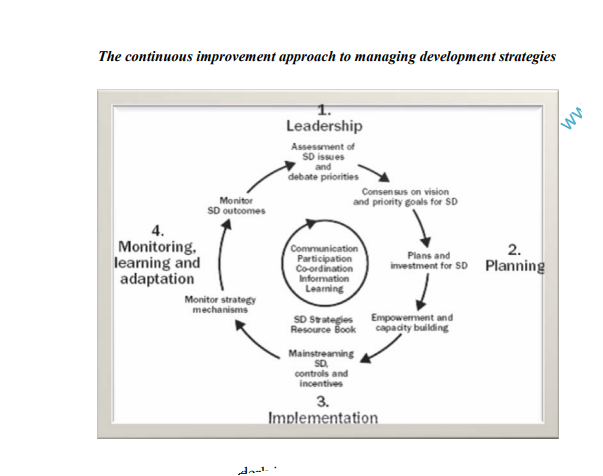

National development strategies over the last few years have identified strategic management as a new pattern of governance and policy making. Being strategic entails developing an underlying vision through consensual, effective and iterative process; and going

on to set objectives, identify the means of achieving them, and then monitor the achievement as a guide to the next round of this learning process.

It also entails shifting grand planning schemes to adaptive strategy processes, from authorities to competencies, from pure hierarchies to a combination of hierarchies and networks, from control to monitoring, evaluation and feedback, and from knowing to learning

are promising steps in the right direction. The success of this shift is typically a function of process aspects such as leadership,

planning, implementation, and monitoring and review. The latter represent some of the fundamental tenets of strategic management.

Leadership – “developing an underlying vision through consensual, effective and iterative process; and going on to set objectives”. Leadership is perhaps the most critical aspect of strategic management. Through a consultative process, it provides the vision for development activities and services. At its foundation, leadership must be grounded in the fundamental principles of sustainable development, that is, it must represent both existing and future generations, and it must understand the interdependency among economic, social and environmental systems. It requires identification of:

- Type of strategy approach

- Demonstrating commitment and focus

- Incorporating the inter-generational SD principle

- Incorporating the interdependency SD principle

Some of the characteristics of leadership include the following:

- people-centered approach;

- strong political commitment;

- consensus and long-term vision;

- sound leadership and good governance;

- comprehensive and integrated (economic, social, and environmental; intergenerational consideration);

- shared strategic and pragmatic vision;

- comprehensive and reliable analysis;

- linking short-term to medium and long-term;

- country led and nationally owned;

- effective participation; and

- Realistic and flexible targets.

Planning – identifying the means of achieving objectives (institutional mechanisms, programmatic structures and specific policy initiatives). It requires identification of:

- Legal basis

- Institutional basis

- Policy assessment

Implementation – employing and financing a mix of policy initiatives Monitoring, learning and adapting – development, monitoring and reporting of indicators to measure:

- Progress in implementing policy initiatives

- The economic, social and environmental state of the nation.

- Also includes formal and informal feedback mechanisms to ensure that monitoring results continually inform the adaptation of leadership, planning and implementation.

Approaches for the Strategy Process

Comprehensive, multi-dimensional SD strategy

A single document and process that incorporates economic, social and environmental dimensions of SD. This approach is most commonly associated with the term National Sustainable Development Strategy. The national strategy provides a long-term perspective of the key SD challenges facing the country, and presents options for addressing priority issue areas. The strategy is described as a catalyst for change, and provides a framework to guide policy development and decision making.

Cross-Sectoral SD strategies relating to specific dimensions of SD

A strategy that spans multiple sectors and covers one or two dimensions of sustainable development, e.g., national environmental management plans or poverty reduction strategy papers (PRSPs). PRSPs describe a country’s macroeconomic, structural, and social policies in support of growth and poverty reduction, as well as associated external financing needs and major sources of financing.

Sectoral SD strategies

A strategy that incorporates economic, social and environmental dimensions of SD, but that is focused on a specific sector. Rather than create a single, national strategy for the government, responsibility for sustainable development to individual government departments and agencies (e.g., SD strategy for a ministry of transportation).

Guiding Principles of Sustainable Development Strategies

- Primacy of Developing Full Human Potential;

- Holistic Science and Appropriate Technology;

- Cultural, Moral and Spiritual Sensitivity;

- Self-Determination;

- National Sovereignty

- Gender Sensitivity;

- Peace, Order and National Unity;

- Social Justice, Inter-, Intra-Generational and

- Spatial Equity;

- Participatory Democracy;

- Institutional Viability;

- Viable, Sound and Broad-Based Economic Development;

- Sustainable Population;

- Ecological Soundness;

- Bio-geographical Equity and Community- Based Resource Management; and

- Global Cooperation.

Regional Integration

Regional integration refers to the process by which states within a particular region increase their level of interaction with regard to economic, security, political, and also social and cultural issues. Regional integration arrangements are mainly the outcome of necessity felt by nation-states to integrate their economies in order to achieve rapid economic development, decrease conflict, and build mutual trusts between the integrated units Closer integration of neighboring economies is seen as a first step in creating a larger

regional market for trade and investment. This works as a spur to greater efficiency, productivity gain and competitiveness, not just by lowering border barriers, but by reducing other costs and risks of trade and investment. Bilateral and sub-regional trading arrangements are advocated as development tools as they encourage a shift towards greater market openness.

Such agreements can also reduce the risk of reversion towards protectionism, locking in reforms already made and encouraging further structural adjustment.

Functions of Regional Integration

- the strengthening of trade integration in the region

- the creation of an appropriate enabling environment for private sector development

- the development of infrastructure programmes in support of economic growth and regional integration

- the development of strong public sector institutions and good governance;

- the reduction of social exclusion and the development of an inclusive civil society

- contribution to peace and security in the region

- the building of environment programmes at the regional level

- the strengthening of the region’s interaction with other regions of the world

Co-operatives and Development

Cooperatives are voluntary organizations that are democratically controlled by members. Cooperatives are also patronized and controlled by their owners and hence the term “owner user” and ‘owner controller’. The concept of cooperatives has sometimes been

misunderstood to the extent that cooperatives have been associated with socialism, communism as a result some governments have not allowed cooperatives to function properly.

It’s vital to note that Cooperatives provide organizational framework which enables the members of the community to handle tasks that enhance production and productivity, marketing and value addition, employment creation thus enhancing incomes and meeting

social needs. For cooperatives to succeed and also benefit the owners, the value of self help must be fully embraced. However, More often than not, one hears a question like what has a cooperative done to assist its members, and yet the valid question would have been how the members have utilized the cooperatives to enhance the socio economic status? Cooperatives differ from other forms of businesses in that they are member centered as contrasted to companies where capital is at the centre in order to earn profits.

Contribution of Cooperatives to Development

Through their varied activities, Cooperatives are in many countries significant social and economic actors in national economies, thus making not only personal development a reality but, contributing to the well being of the entire humanity at the national level.

Production and productivity enhancement: Cooperatives play an important role in delivery of agricultural in puts so that they are easily accessed by the producers. Such in puts are required by farmers to increase productivity and produce good quality, increase farm income and become more competitive. i.e. they form a link between farmers and input dealers. Since they are organized, they can readily afford hiring of agricultural extension services all aimed at production and productivity improvement.

Infrastructure development: Through pooling resources members are able to put up infrastructure for production, agro-processing and marketing e.g. establishment of ginneries processing plants e.g. coffee hullers, dairy products processing, storage facilities market

information, agro processing and value addition. Employment creation: where there is a well functioning cooperative organization at

least 2 people are employed directly and many others indirectly through various trades facilitated by a cooperative.

Investment opportunities: by investing shares into a well performing and genuine cooperative returns are generated on shares and depending on how one has economically patronized the organization, patronage bonus is always paid

Financial intermediation: Availability of financial services helps farmers in a number of ways. Farmers can be able to get in puts in time through the available credit services. Secondly when farmers products are bulked in the stores while awaiting better markets, farmers can borrow from their own SACCOs to cater for their pressing needs as they wait for marketing of their products.

Social services provision: These include among others health, housing, utilities e.g. rain water harvesting, solar power scheme, and transport-bodaboda.

Human resources development: All round training is always provided to membership, staff and leaders of any genuine and well performing cooperative organization

Social Impact of Co-operatives

By putting cooperative principles and values and ethos in practice, they promote solidarity, tolerance and accountability; while as schools of democracy, they promote the rights of each individual-women and men. Cooperatives are socially conscious responding to the needs of their members whether it is to provide literacy or technical training. Through partnership building they are able to tackle social issues like HIV/AIDS pandemic, environmental conservation among other things. Through their varied activities, cooperatives are in many countries significant social and economic actors in national economies, thus making not only personal development a

reality but, contributing to the well being of the entire humanity at the national level.

Natural Resources and Development

Natural resources are distinguished by their renewability and ownership regimes. Renewable resources include forests, fisheries and wildlife. Exhaustible resources include minerals that can only be replenished over geologic time. Ownership regimes frequently dictate

the rate at which natural resources are degraded, with open-access regimes often leading to the highest levels of degradation. The use of natural resources also poses difficult social and distributive questions. Poverty can lead to unsustainable use and environmental degradation, and threatens fragile ecosystems. The poor suffer disproportionately from over-exploitation and degradation of

resources, yet they lack sufficient political or economic representation.

Disputes over natural resources could therefore arise for a number of reasons: Actions of one group may intentionally or unintentionally impinge upon the ecological well-being of others. Those with greater access to power also tend to control natural resource use and distribution. As well, rapid environmental change, unequal distribution of power, and changing consumption patterns exacerbate natural resource scarcity. This can lead to fierce competition between groups impacting on development negatively. Finally, people define natural resources in ideological, social, and political terms. Thus, land, forests, and waterways not only represent material resources that people struggle over, but are often culturally and symbolically important.

Because natural resource conflicts are complex, pluralistic approaches are more effective in identifying barriers to progress and peace building strategies. Multi-stakeholder analysis, in particular, offers researchers and policymakers an effective means of understanding

the different interests and power relations among those involved. Various research methods can further enhance this approach. They include participatory rural appraisal, participatory action research, gender analysis, and the analysis of differences in class interests and power relations. Greater opportunities for change emerge when local stakeholders are involved in analyzing the causes and alternatives to conflict.

However, conflict-resolution strategies have limitations. Collaborative approaches such as conciliation, negotiation and mediation based on western experiences with alternative dispute resolution (ADR) may not work in conflicts involving natural resources.

ADR techniques require both cultural and legal conditions, such as a willingness to publicly acknowledge conflict, the voluntary participation of all relevant actors, and administrative and financial support. Such conditions may prove elusive in many contexts in

both North and South. Moreover, ADR may lead to greater frustration if the causes of conflict remain beyond the stakeholders’ understanding and control. At the same time, Western traditions of conflict management must be balanced with the study of local practices, insights, and resources. Even more important, they note, conflict itself may be a catalyst for positive social change in certain circumstances, but only if violence can be avoided.